Abstract

Rationale and Objectives

Mammography quality assurance programs have been in place for over a decade. We studied radiologists’ self-reported performance goals for accuracy in screening mammography and compared them to published recommendations.

Materials and Methods

A mailed survey of radiologists at mammography registries in seven states within the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC) assessed radiologists’ performance goals for interpreting screening mammograms. Self-reported goals were compared to published American College of Radiology (ACR) recommended desirable ranges for recall rate and false positive rate, positive predictive value of biopsy recommendation (PPV2), and cancer detection rate. Radiologists’ goals for interpretive accuracy within desirable range were evaluated for associations with their demographic characteristics, clinical experience and receipt of audit reports.

Results

The survey response rate was 71% (257 of 364 radiologists). The percentage of radiologists reporting goals within desirable ranges was 79% for recall rate, 22% for false positive rate, 39% for PPV2, and 61% for cancer detection rate. The range of reported goals was 0 to 100% for false-positive rate and PPV2. Primary academic affiliation, receiving more hours of breast imaging continuing medical education (CME), and receiving audit reports at least annually were associated with desirable PPV2 goals. Radiologists reporting desirable cancer detection rate goals were more likely to have interpreted mammograms for 10 or more years, and > 1,000 mammograms per year.

Conclusion

Many radiologists report goals for their accuracy when interpreting screening mammograms that fall outside of published desirable benchmarks, particularly for false positive rate and PPV2, indicating an opportunity for education.

Keywords: screening mammography, accuracy, goals, false positive rate

INTRODUCTION

Of all the specialties within radiology, breast imaging lends itself to the objective assessment of interpretive performance. As information technology infrastructure in medicine develops, more specialties may be added. Benchmarks for desirable interpretation in breast imaging have been published for the U.S. and Europe 1-3. Many countries now mandate that audit performance data be collected and reviewed so that administrators and radiologists know how well they are performing 4, 5. It is not clear, however, what impact the efforts to collect and review audit data are having on individual radiologists, or whether radiologists have goals for their own performance that align with published benchmarks.

Educational studies have shown that when clinicians understand that a gap exists between their performance and national targets, they can be predisposed to change their behavior 7, 8. Interpretive accuracy in mammography could be improved if radiologists are motivated by recognizing a gap between their individual performance and desirable benchmarks. One web-based continuing medical education (CME) intervention utilized individual radiologist’s own recall rate data and compared it to rates of a large cohort of their peers 9. Radiologists with inappropriately high recall rates were able to come up with specific plans to improve their recall rates based upon this recognition of a need to improve. For improvements to occur, radiologists must recognize the difference between their own performance and desired targets, which is potentially feasible given collection and review of MSQA audit data. However, it is not clear if radiologists are aware of common desirable performance goal ranges.

In this study, we surveyed a large number of community-based radiologists all working in breast imaging and asked them to indicate their personal goals for interpretive performance. We sought to determine the proportion of radiologists’ personal performance goals within published benchmarks and which, if any, characteristics of the radiologists and their practices would be associated with having goals within desirable benchmarks.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All radiologists who interpreted screening mammograms in 2005-2006 in the National Cancer Institute-funded Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC) 10, 11 were invited to complete a self-administered mailed survey. This included seven sites representing distinct geographic regions of the U.S. (California, Colorado, North Carolina, New Mexico, New Hampshire, Vermont, and Washington). Most radiologists participating in the consortium are community-based, and routinely receive audit reports 12. All procedures were Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act compliant, and all BCSC sites and the Statistical Coordinating Center received a Federal Certificate of Confidentiality and other protection for the identities of the physicians who are subjects of this research. Institutional Review Boards (IRB) of the study university and all seven BCSC sites approved the study.

Design, Testing, and Radiologist Survey Administration

The survey was developed by a multi-disciplinary team of experts in breast imaging, clinical medicine, health services research, biostatistics, epidemiology, behavioral sciences, and educational psychology, and was extensively pilot-tested. The content and development of the survey have been previously described in detail 6. Our primary outcomes included self-reported goals for various measures of interpretive performance. Radiologists were asked to report their goal or value they would like to achieve for recall rate, false positive rate, positive predictive value of biopsy recommendation (PPV2), and cancer detection rate per 1000 screening mammograms. All performance measures were defined in the survey (Table 1). We also assessed the frequency with which radiologists received performance audits (none, once per year, more than once per year)6.

Table 1.

Definitions of mammography performance measures and goals

| Performance measure | Survey definition | BI-RADS manual definition* | 25-75 percentile performance ranges noted in Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium† | Desirable performance goals‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recall rate | % of all screens with a positive assessment leading to immediate additional work-up | The percentage of examinations interpreted as positive (for screening exams BI-RADS categories 0, 4, and 5, for diagnostic exams BI-RADS 4 and 5 assessments). | 6.4-13.3% | 2-10%§ |

| RR= (positive examination)/(all examinations) | ||||

|

| ||||

| False positive rate | % of all screens interpreted as positive and no cancer is present | Not available | 7.5-14.0% | 2-10%§ |

|

| ||||

| Positive predictive value of biopsy recommendation (PPV2) | % of all screens with biopsy or surgical consultation recommended that resulted in cancer | The percentage of all screening or diagnostic examinations recommended for biopsy or surgical consultation (BI-RADS categories 4 and 5) that resulted in a tissue diagnosis of cancer within one year. PPV2 = True positive/(number of screening or diagnostic examinations recommended for biopsy) | 18.8-32.0% | 25-40% |

|

| ||||

| Cancer detection rate | # of cancers detected by mammography per 1000 screens | The number of cancers correctly detected at mammography per 1,000 patients examined at mammography. | 3.2-5.8% | 2-10% |

American College of Radiology. ACR BI-RADS - Mammography. 4th ed. Reston, VA: American College of Radiology; 2003.

Rosenberg, RD, Yankaskas, BC, Abraham, LA, et al. Performance Benchmarks for Screening Mammography. Radiology 241(1) 55-66, and false positive rate from BCSC website (http://breastscreening.cancer.gov/data/bcsc_data_definitions.pdf)

Bassett LW, Hendrick RE, Bassford TL. Et al. Quality determinants of mammography. Clinical Practice Guideline No. 13. AHCPR Publication No. 95-0632. Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, Public Health Service, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, October 1994: 83

Modified from BI-RADs manual “desirable” goals because 0-2% recall rate and false positive rate are not considered realistic

Surveys (available online at http://breastscreening.cancer.gov/collaborations/favor_ii_mammography_practice_survey.pdf). were administered to radiologists between January 2006 and September 2007, depending on each BCSC site’s funding mechanism and IRB status. Incentives to complete the survey varied among the seven sites and included bookstore gift cards worth $25-$50 for radiologists (seven sites) and for mammography facility administrators and/or technologists (four sites), as well as the fourth edition of the BI-RADS manual 2 for participating facilities (four sites). Once each site obtained completed surveys with informed consent, the data were double-entered and discrepancies were corrected. Encrypted data were sent to the BCSC Statistical Coordinating Center for pooled analyses.

Definition of Desirable Performance Goals

Recommendations from the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (AHRQ) 1994 clinical practice guideline and the Breast Imaging and Reporting Data System (BI-RADS) manual published by the American College of Radiology (ACR) were used to develop a list of “desirable goals” for mammography performance outcomes 2, 13. Although these goals were not considered guidelines for current medical practice in the U.S., they represent the most recent consensus statement regarding target ranges for accuracy in mammography interpretation. We defined desirable performance goals based on the BI-RADS manual for recall rate, PPV2, and cancer detection rate 2. While false positive rate is not explicitly defined in the BI-RADs manual, it is easily calculated (1-specificity) and was included in this study. We modified the lower bound of recall rate and false positive rate to exclude 0-2%, because rates lower than 2% would not be considered desirable or realistic in the U.S. for mammography screening. The desirable performance ranges we used for analysis were recall rate 2-10%, false positive rate 2-10%, PPV2 25-40%, and cancer detection rate 2-10 per 1,000 screening exams (Table 1).

We also compared radiologists’ self-reported goals to the published U.S. benchmark 25-75% range of performance for BCSC radiologists 14, and those of their highest performing peers, defined as the lowest 0-24 percentile for recall and false positive rates, and highest 76-100 percentiles for PPV2 and cancer detection rates. We used this cohort of radiologists for comparison because it is a very large, generalizable sample of community radiologists from seven U.S. geographic regions for whom well-documented performance measures are available. The BCSC performance ranges are based on 4,032,556 screening mammography examinations performed between 1996 and 2005 at 152 mammography facilities by 803 radiologists. The BCSC inter-quartile ranges were: recall rate 6.4-13.3%, false positive rate 7.5-14.0%, PPV2 18.8-32.0%, and cancer detection rate 3.2-5.8/1,000 screening exams (Table 1) 14, 15.

Statistical Analysis

We calculated the proportions of radiologists who reported performance goals within the desirable range, goals above and below the range, and among those who did not respond. For some analyses, these categories were further collapsed into within desirable range versus outside of range. For such analyses, we assumed that “no response” indicated that a radiologist had performance goals outside of the desirable range. Because 13.6% (35/257) of radiologists did not respond to items on performance goals, we also examined a restricted cohort limited to radiologists who responded to at least one of these items (n=222). In addition, we determined the proportion of radiologists whose self-reported performance goals fell within the U.S. inter-quartile performance range of BCSC radiologists.

We then used chi-squared statistics to assess associations between having goals within desirable range or not and radiologist characteristics (demographics, practice type, breast imaging experience, mammography volume, and audit frequency). Finally, we repeated these analyses with the restricted cohort described above. All statistically significant associations are reported at the P<0.05 level, and p-values are two-sided. Data analyses were conducted by using SAS® software, Version 9.2 (SAS institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

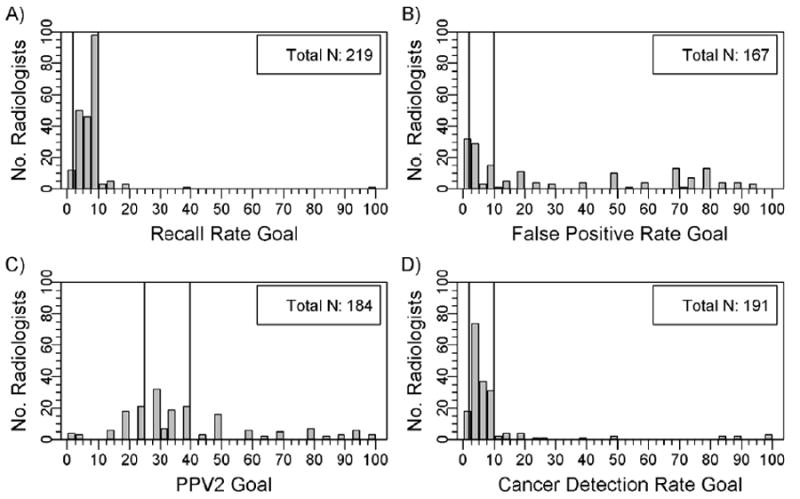

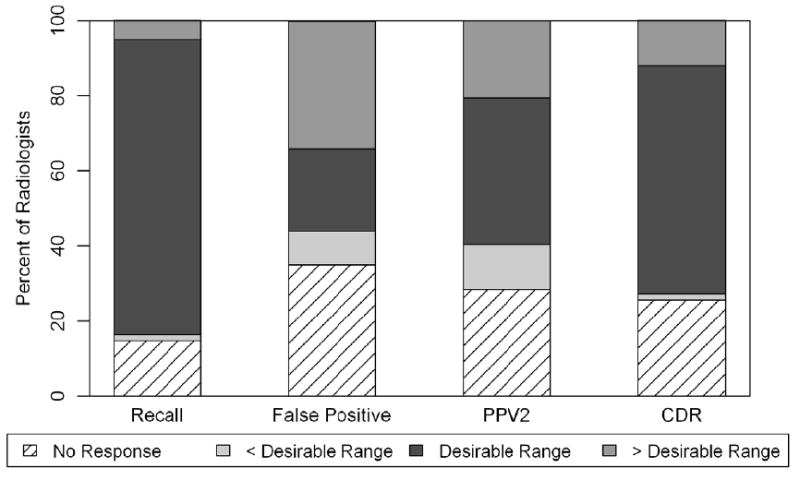

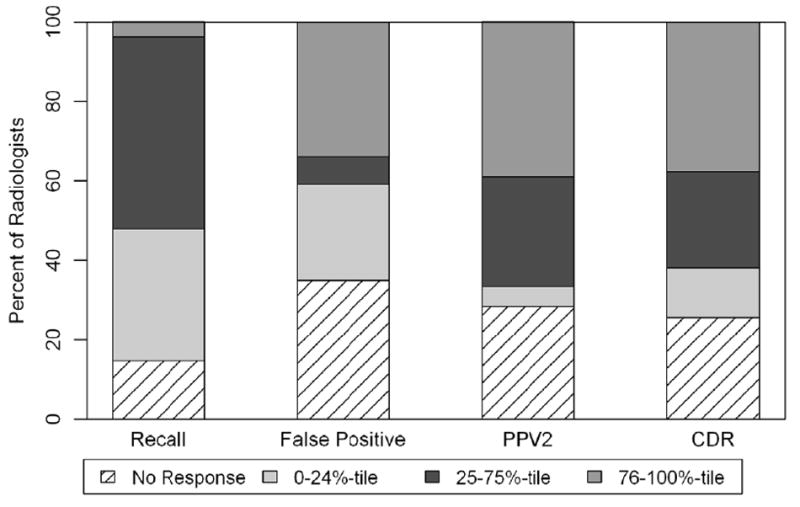

Of 364 eligible radiologists, 257 (71%) responded to the survey and 222 completed question(s) related to performance goals. Figure 1 demonstrates the distribution of radiologists’ stated performance goals; many false positive rates and PPV2 goals fall well above the desirable range. The percentage of radiologists reporting goals within the desirable range was 79% for recall rate, 22% for false positive rate, 39% for PPV2, and 61% for cancer detection rate (Figure 2A). Radiologists were more likely to report goals above the desirable range for false positive rate and PPV2 than for recall and cancer detection rates. A much smaller proportion of the reported goals fell within the BCSC interquartile range (25-75%): recall rate 48%, false positive rate 7%, PPV2 28%, and cancer detection rate 24%(Figure 2B). Those with goals consistent with the highest performing quartile of their peers included: recall rate 33%, false positive rate 24%, PPV2 39% and cancer detection rate 38%.

Figure 1.

Radiologists’ self-reported goals for performance measures: A) recall rate, B) false positive rate, C) positive predictive value of biopsy, and D) cancer detection rate per 1000 screening mammograms. Vertical lines indicate the desirable goal ranges.

Figure 2.

A and B. Radiologists’ reported performance goals for recall, false positive rate, PPV2, and cancer detection rates (CDR) relative to desirable goal ranges and peer cohort benchmarks

A. Radiologists’ performance goals relative to American College of Radiology desirable goal ranges categorized by no response, less than desirable range, greater than desirable range, and within desirable range.

B. Radiologists’ performance goals relative to peer cohort benchmark quartiles, categorized by no response, lowest quartile (0-24%), average performance (25%-75%), and highest quartile (76-100%).

Radiologists’ performance goals stratified by radiologist characteristics are shown in Table 2. Most radiologists were men (72%), not affiliated with an academic medical center (81%), and working more than 40 hours per week in breast imaging (60%). No radiologist characteristics were significantly associated with reporting goals within the desirable range for recall rate or false positive rate. PPV2 goals within the desirable range were associated with having a primary academic affiliation; completing 30 or more hours of breast imaging CME over the past three years (compared to ≥15 hours); and receiving more than one audit report per year. Radiologists between 45-54 years of age; interpreting mammograms for 10-19 years compared to <10 years; and with annual interpretive volume >1,000 mammograms/year were more likely to report desirable cancer detection rate goals (Table 2). When the analyses were repeated with the cohort limited to radiologists who answered at least one of the questions on performance goals (n=222), relationships between radiologists characteristics and outcome measures did not change (data not shown).

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical experience characteristics of radiologists and their self-reported mammography performance goals within desirable goal ranges.

| Total | % of radiologists with self-reported performance goals within desirable goal range* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recall | False Positive | PPV2 | Cancer Detection | ||

| Characteristic | N | ||||

| Total | 257 | 79 | 22 | 39 | 61 |

|

| |||||

| Demographics | |||||

|

| |||||

| Age at survey | |||||

| 34-44 | 69 | 72 | 20 | 36 | 52 |

| 45-54 | 89 | 85 | 26 | 45 | 74 |

| ≥55 | 99 | 77 | 19 | 35 | 55 |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 184 | 78 | 22 | 37 | 62 |

| Female | 73 | 79 | 22 | 44 | 58 |

|

| |||||

| Practice Type | |||||

|

| |||||

| Affiliation with academic medical center | |||||

| No | 208 | 77 | 21 | 38 | 61 |

| Adjunct | 24 | 75 | 29 | 25 | 50 |

| Primary | 22 | 95 | 27 | 64 | 73 |

|

| |||||

| Breast Imaging Experience | |||||

|

| |||||

| Fellowship training | |||||

| No | 236 | 77 | 21 | 38 | 60 |

| Yes | 21 | 95 | 29 | 48 | 71 |

| Years of mammography interpretation | |||||

| <10 | 56 | 73 | 16 | 36 | 50 |

| 10-19 | 91 | 82 | 20 | 44 | 69 |

| ≥20 | 109 | 79 | 27 | 37 | 60 |

| Hours working breast imaging | |||||

| 0-30 | 42 | 79 | 24 | 38 | 62 |

| 31-40 | 57 | 82 | 21 | 37 | 63 |

| > 40 | 155 | 77 | 21 | 40 | 59 |

| Number of breast imaging CME hours/3 yr reporting period | |||||

| 15 hr minimum | 65 | 71 | 20 | 28 | 54 |

| >15 hrs, but < 30 hrs | 116 | 78 | 21 | 38 | 61 |

| 30 hrs or more | 74 | 86 | 26 | 50 | 66 |

|

| |||||

| Volume | |||||

|

| |||||

| Self-reported average # of mammograms per year over the past 5 years | |||||

| Total: | |||||

| <= 1000 | 25 | 76 | 20 | 24 | 40 |

| 1001-2000 | 81 | 75 | 23 | 37 | 65 |

| >= 2000 | 134 | 84 | 22 | 42 | 65 |

|

| |||||

| Audit reports | |||||

|

| |||||

| Receive audit reports | |||||

| Never | 22 | 82 | 14 | 14 | 50 |

| Once/year | 157 | 84 | 24 | 41 | 64 |

| > once/year | 57 | 75 | 21 | 51 | 68 |

Desirable goal ranges were defined as 2-10% for recall rate and false positive rate, 25-40% for PPV2, and 2-10 per 1,000 screening mammograms for cancer detection rate. Radiologists that did not respond to the question were defined as having goals outside of desirable goal range.

BOLD indicates statistical significance at the 0.05-level

Only 21 of 257 (8%) radiologists received fellowship training in breast imaging, and although a higher proportion of this group reported performance goals within the desirable range these findings did not achieve statistical significance.

When the analysis was limited to radiologists who answered at least one of the questions on performance goals (n=222), 90% fell within the desirable range for recall rate, 25% for false positive rate, 45% for PPV2, and 70% for cancer detection rate. In this subgroup, the proportion of radiologists reporting goals that fell within the BCSC interquartile range (25-75%) were: recall rate 56%, false positive rate 8%, PPV2 32%, and cancer detection rate 28%. data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Quality assurance programs for breast cancer screening services are intended to utilize audit data to improve clinical outcomes 3, 4, and helping clinicians understand the gap between their own performance and national targets has been demonstrated to predispose physicians to change 7, 8. In this study, many radiologists reported goals for their interpretive performance that were either above or below published desirable benchmarks. Self-reported goals for recall rate and cancer detection rate, two measures well understood by interpreting radiologists, were most closely aligned with published goal ranges. For false positive rate and PPV2, a majority of radiologists reported goals that fell outside of desirable ranges, with relatively even dispersion of reported goals between 0 and 100%. This indicates that many radiologists are not familiar with false positive rate and PPV2 or they have unrealistic goals for these measures.

For over a decade the Mammography Quality Standards Act (MQSA) has legislated that radiologists review mammography outcome data4, however a 2005 Institute of Medicine report on Improving Breast Imaging Quality Standards 16 noted that interpretation by radiologists remains quite variable. Attempts to identify predictors of accuracy in mammography interpretation have studied a wide array of potential characteristics, and found that fellowship training was the only trait associated with better interpretive performance 6. Another study suggested that a learning curve exists, peaking approximately five years after completion of residency 17. Thus education of motivated radiologists may have the potential to improve mammography interpretation, including shifting the learning curve forward in time.

Education plays a role in this study also. Radiologists with more hours of CME in breast imaging and primary affiliations with academic medical centers were more likely to report PPV2 goals within desirable range. Receiving audit feedback at least annually was also associated with PPV2 goals within range. One study of community U.S. radiologists with high recall rates demonstrated the practical application of the combination of education and audit feedback, by using web-based CME to compare their recall rates to their peers’ and motivate them to set appropriate recall rate goals 9. Education is used in the United Kingdom for radiologists participating in the Breast Screening Program who train biannually using test sets, and if indicated, receive additional training specific to their areas of identified weakness 18. Before specific education to improve radiologists’ performance can occur, radiologists must be motivated to improve by recognizing the gap between their own performance and desired ranges.

The medical audit is recognized as one of the best quality assurance tools because it can identify performance strengths and weaknesses. In contrast to many European countries 3, audit feedback to radiologists in the U.S. is variable in content and format 12 Recall and cancer detection rates were clearly identified on all audit reports received by radiologists in this study 12, and were the measures most reported within desirable range. In contrast, false positive rate was not explicitly presented in any audit, and only some of the audits reported PPV2 by name 12. Thus, our findings suggest that clear, specific reporting of individual performance feedback juxtaposed with desirable ranges could help radiologists visualize their own performance gap, and theoretically motivate them to take the next step towards wanting to find specific ways to improve.

In many European Union (E.U.) countries, radiologists typically specialize in breast imaging and interpret high volumes of mammograms, 5,000 exams/year or more 18. In the U.S., however, radiologists are often not breast specialists and annual volumes of exams required of radiologists are relatively low (480 screening mammograms per year). Studies of radiologists’ volume and accuracy, though not consistent, have generally found that radiologists interpreting higher volumes have lower false positive rates without increased cancer detection 19, 20. In this study, community practicing radiologists identifying desirable goals for cancer detection were more likely to have greater interpretive volume and more years interpreting.

While most radiologists reported goals within desirable range for recall rate (79%), few reported goals within desirable range for false positive rate (22%). False positive rate is not explicitly defined in ACR guidelines, and radiologists had the most difficulty identifying appropriate goals for this measure. Recall rate and false positive rate are numerically similar because the small number of cancers in a screening population (4.7 cancers per 1,000 screening exams) means that most mammograms that are recalled are false positive 14. The significance of false positive exams has been highlighted in the literature 21-23, frequently discussed in the lay press 24, and the potential harms of over diagnosis are increasingly being acknowledged 25. It is possible that clearly defining false positive rate in future guidelines and explicitly reporting this rate in audit data could improve radiologists’ awareness and understanding of this commonly used measure. In conceptual terms, it is important for radiologists to understand their false positive rates, because while working toward maximizing cancer detection, they should attempt to minimize the burden of false positive work-ups.

A unique strength of the present study is our comparison of study radiologists’ reported goals with the actual benchmark performance of a large cohort of community practicing radiologists from the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC), demonstrating that radiologists’ reported goals did not emulate the accuracy of their highest performing peers. Other strengths include the participation of a large number of community radiologists, the survey response rate of 71%, which is higher than the rate for most physician surveys 26, and the availability of detailed information on the audits received by the radiologists.

One limitation of our study is that it did not address whether individual radiologists whose performance goals fall within desirable ranges are more likely to have better actual interpretive performance. Given the clinical relevance of this point, additional work is recommended to assess a potential link. It is also important to note that 35 radiologists did not respond to any of the survey items on performance goals. Of these 35 radiologists, all but one responded to two subsequent survey items about CME. Thus their non-response seems unrelated to survey fatigue.

In conclusion, many radiologists in our study reported goals for their own interpretation of screening mammograms that fall outside of published desirable benchmarks, particularly for false positive rate and PPV2. Knowledge of desirable performance ranges is a necessary step in interpreting audit data14. Further work is warranted to evaluate whether explicitly defining and reporting target goals on individual performance audits results in improved understanding by radiologists of their own level of performance, and ultimately in improved clinical accuracy.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (1R01 CA10762), the National Cancer Institute (1K05 CA104699; Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium: U01CA63740, U01CA86076, U01CA86082, U01CA63736, U01CA70013, U01CA69976, U01CA63731, U01CA70040), the Breast Cancer Stamp Fund, and the American Cancer Society, made possible by a generous donation from the Longaberger Company’s Horizon of Hope Campaign (SIRGS-07-271-01, SIRGS-07-272-01, SIRGS-07-273- 01, SIRGS-07-274-01, SIRGS-07-275-01, SIRGS-06-281-01). We thank the participating mammography facilities and radiologists for the data they have provided for this study. A list of the BCSC investigators and procedures for requesting BCSC data for research purposes are provided at: http://breastscreening.cancer.gov/. We also thank Raymond Harris, Ph.D., for his careful review and comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Feig SA. Auditing and benchmarks in screening and diagnostic mammography. Radiol Clin North Am. 2007;45(5):791–800. vi. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American College of Radiology. ACR BI-RADS - Mammography. 4. Reston, VA: American College of Radiology; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perry N, Broeders M, de Wolf C, Tornberg S, Holland R, von Karsa L. European guidelines for quality assurance in breast cancer screening and diagnosis. Fourth edition--summary document. Ann Oncol. 2008;19(4):614–622. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.US Food and Drug Administration/Center for Devices and Radiological Health. [2 May, 2011];US FDA/CDRH: Mammography Program. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/cdrh/mammography.

- 5.EUREF European Reference Organisation for Quality Assured Breast Screening and Diagnostic Services. [Accessed 2 May, 2011]; Available at: http://www.euref.org/

- 6.Elmore JG, Jackson SL, Abraham L, et al. Variability in interpretive performance at screening mammography and radiologists’ characteristics associated with accuracy. Radiology. 2009;253(3):641–651. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2533082308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Speck M. Best practice in professional development for sustained educational change. ERS Spectrum. 1996;14:33–41. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laidley TL, Braddock IC. Role of Adult Learning Theory in Evaluating and Designing Strategies for Teaching Residents in Ambulatory Settings. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2000;5(1):43–54. doi: 10.1023/a:1009863211233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carney PA, Bowles EJ, Sickles EA, et al. Using a tailored web-based intervention to set goals to reduce unnecessary recall. Acad Radiol. 2011;18(4):495–503. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2010.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ballard-Barbash R, Taplin SH, Yankaskas BC, et al. Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium: A national mammography screening and outcomes database. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;169:1001–1008. doi: 10.2214/ajr.169.4.9308451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (NCI) [2 May, 2011];BCSC Collaborations: FAVOR. Available at: http://www54.imsweb.com/collaborations/favor.html.

- 12.Elmore JG, Aiello Bowles EJ, Geller B, et al. Radiologists’ attitudes and use of mammography audit reports. Acad Radiol. 2010;17(6):752–760. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2010.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bassett LW, Hendrick RE, Bassford TL, et al. Clinical practice guideline No 13. Rockville: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1994. Quality determinants of mammography. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosenberg RD, Yankaskas BC, Abraham LA, et al. Performance benchmarks for screening mammography. Radiology. 2006;241(1):55–66. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2411051504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Breast Cancer Screening Consortium. [2 May, 2011];BCSC Screening Performance Benchmarks. 2009 Available at: http://breastscreening.cancer.gov/data/benchmarks/screening.

- 16.Nass S, Ball JE. Institute of Medicine. Improving Breast Imaging Quality Standards. Washington, D.C: The National Academies Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miglioretti DL, Gard CC, Carney PA, et al. When radiologists perform best: the learning curve in screening mammogram interpretation. Radiology. 2009;253(3):632–40. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2533090070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perry N. Interpretive skills in the National Health Service Breast Screening Programme: Performance indicators and remedial measures. Seminars in Breast Disease. 2003;6(3):108–113. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buist DS, Anderson ML, Haneuse SJ, et al. Influence of Annual Interpretive Volume on Screening Mammography Performance in the United States. Radiology. 2011;259(1):72–84. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10101698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hebert-Croteau N, Roberge D, Brisson J. Provider’s volume and quality of breast cancer detection and treatment. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;105(2):117–132. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9439-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fletcher SW, Elmore JG. False-positive mammograms--can the USA learn from Europe? Lancet. 2005;365(9453):7–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17676-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lindfors KK, O’Connor J, Parker RA. False-positive screening mammograms: effect of immediate versus later work-up on patient stress. Radiology. 2001;218(1):247–253. doi: 10.1148/radiology.218.1.r01ja35247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brewer NT, Salz T, Lillie SE. Systematic review: the long-term effects of false-positive mammograms. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(7):502–510. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-7-200704030-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Allen S. Cancer scares grow as screening rises better tests sought to reduce anxiety The Boston Globe. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nelson HD, Tyne K, Naik A, Bougatsos C, Chan BK, Humphrey L. Screening for breast cancer: an update for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(10):727–737. W237–742. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-151-10-200911170-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Asch DA, Jedrziewski MK, Christakis NA. Response rates to mail surveys published in medical journals. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50(10):1129–1136. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00126-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]