Abstract

Introduction

There are knowledge gaps regarding the needs of cancer survivors in Connecticut and their utilization of supportive services.

Methods

A convenience sample of cancer survivors residing in Connecticut were invited to complete a self-administered (print or online) needs assessment (English or Spanish). Participants identified commonly occurring problems and completed a modified version of the Supportive Care Needs Survey Short Form (SCNS-SF34) assessing needs across five domains (psychosocial, health systems/information, physical/daily living, patient care /support, and sexuality).

Results

The majority of the 1,516 cancer survivors (76.4%) were women, 47.5% had completed high school or some college, 66.1% were diagnosed ≤ 5 years ago, and 87.7% were non-Hispanic white. Breast was the most common site (47.6%), followed by prostate, colorectal, lung, and melanoma. With multivarite adjustment, need on the SCNS-SF34 was greatest among women, younger survivors, those diagnosed within the past year, those not free of cancer, and Hispanics/Latinos. We also observed some differences by insurance and education status. In addition, we assessed the prevalence of individual problems; with the most common being weight gain/loss, memory changes, paying for care, communication, and not being told about services.

Conclusions

Overall and domain specific needs in this population of cancer survivors were relatively low, although participants reported a wide range of problems. Greater need was identified among cancer survivors who were female, younger, Hispanic/Latino, and recently diagnosed.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

These findings can be utilized to target interventions and promote access to available resources for Connecticut cancer survivors.

Keywords: cancer survivors, needs assessment, psychosocial, supportive care

Introduction

A cancer survivor is defined as any person who has been diagnosed with cancer from point of diagnosis through the remaining years of life. Cancer survivorship is a distinct phase in the cancer control continuum [1]. The number of cancers survivors has been increasing over the past three decades due to improved early detection rates and therapeutic advances. As of 2007, there were approximately 11.7 million cancer survivors in the U.S., representing 4% of the population [2]. The most prevalent cancer diagnoses among survivors are breast (23%), prostate (20%), colorectal (10%) and gynecologic (9%) cancers.

Cancer incidence varies in the U.S., with the Northeast having higher incidence rates for the most prevalent cancers (breast, prostate, colorectal and lung) than other areas of the country [3]. Similar to national rankings, cancer is the second leading cause of death in Connecticut [4, 5]. High incidence rates combined with some of the lowest cancer-related mortality rates [6], gives Connecticut a burgeoning cancer survivor population.

The transition to survivorship following cancer treatment is often challenged by persistent or long term physical effects, late effects, psychological and existential distress, informational needs, changes in social support, and practical concerns for managing everyday life [1, 7-12]. Persistent or long term physical effects include symptoms, such as fatigue, that continue after cancer treatment and either resolve or become chronic. Late effects, such as cardiac toxicity, are those that occur months to years after cancer treatment. Both persistent and late effects are unique to the cancer type and specific cancer treatment therapy [1, 11, 13] Psychological needs are more universal and include fear of recurrence, uncertainty, decreased social support, changes in mood, existential concerns, as well as challenges to re-integration into family, social, and employment roles [1]. While physical, psychological, informational and social support needs have been identified for cancer survivors, health care providers and agencies still lack the data necessary to help meet the needs of specific cancer survivor populations (e.g. by age and ethnic background). Thus, additional data are needed to develop and appropriately target interventions as well as facilitate access to resources for cancer survivors to promote overall health and optimal quality of life.

A recent review found wide variation in the prevalence of unmet supportive care-related needs, with differences based on active treatment or completion of treatment [12]. Prevalence of unmet need in cross-sectional studies of survivors has ranged from 30 to 50% [14-18]. However, the studies included in this review utilized many different instruments in heterogeneous cancer populations, making the results difficult to compare [12]. Importantly, research suggests that the presence of unmet needs can be detrimental to quality of life [19, 20].

To better understand the specific needs of cancers survivors in Connecticut, the Connecticut Cancer Partnership’s (CCP) Survivorship Committee recommended a needs assessment of this population. The CCP is the voluntary comprehensive cancer control coalition in Connecticut, recognized by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, to work in partnership with the state Department of Public Health in supporting a coordinated approach to comprehensive cancer control. Working across the entire cancer continuum, the CCP has attempted to advocate for funding and support meaningful implementation programs to help reduce the burden of cancer on Connecticut’s residents. Since many support services for cancer survivors exist in Connecticut, but are often unknown or underutilized by the populations for which they are designed, these findings can be utilized to target services and resources in the future.

Methods

Study Population

Cancer survivors residing in Connecticut were invited to complete a self-administered (print or online) survivorship needs assessment survey (available in English or Spanish) between September 2008 and April 2009. Many strategies were employed to recruit the convenience sample of cancer survivors, including development of partnerships with organizations and institutions providing cancer related care and information, outreach at one-time cancer-related events, collaboration with individual cancer care providers and professional agencies, and contact with organizations serving ethnic minority populations. Various marketing methods were also used, including advertising on radio stations, TV channels, newspapers, and in the public libraries of 15 cities and towns across Connecticut. Additionally, a one-time insert about the needs assessment was included in state employees’ paycheck envelopes, reaching over 80,000 individuals.

Survey Questionnaire

The self-administered survey instrument included questions on sociodemographics (e.g. gender, age, education, marital status, income, ethnicity), health behaviors (e.g. smoking, physical activity), and a one item depression screener [21]. Insurance status at the time of completing the survey was also queried with the following options: private, Medicaid, Medicare, not covered, and other. These were collapsed into four groups: Medicaid only, Medicaid and private; Medicare only, Medicare with Medicaid; private only, other; and Medicare and private. Participants also reported on several areas of their cancer history, including the year of their first cancer diagnosis, number and types of cancers experienced in their lifetime, the year of their most recent cancer diagnosis, and if they were cancer free at the time of the survey. In addition, participants were asked about where they obtained information regarding their cancer and which sources were most helpful.

A modified version of the validated Supportive Care Needs Survey 34 item short form SCNS-SF34 [22] was included in the survey to assess participant needs. The SCNS-SF34 evaluates needs during the previous month across five domains: psychological, health system and information, physical and daily living, patient care and support, and sexuality. The SCNS-SF34 was ideal as it was on built on pre-existing needs assessments and has 7th to 8th grade literacy level with an easy to understand format using a 5-point Likert scale (1=not applicable/not a problem, 2=satisfied, 3=low need, 4=moderate need, 5=high need). Ten additional questions were added to the questionnaire to help capture the needs of the more diverse Connecticut population. Six of the additional items were taken from the SCNS-Long Form [23] and the remaining four items were recommended by the survivorship committee of the CCP.

Finally, based on a literature review, data generated by focus groups and community based forums (full description below), and consultations with oncology experts in the CCP, 18 commonly occurring problems/barriers experienced by cancer survivors were identified. Participants were asked to report how much of a problem each item had been during the previous month (1=not a problem, 2=somewhat of a problem, 3=a severe problem).

Community Forums

The purpose of the community forums was to target populations who might be less likely to complete surveys individually. A variety of outreach strategies were used in collaboration with community partners to target men, younger survivors, and minorities for these forums. Each forum was attended by at least two staff, one facilitator, and one note taker and focused on three topic areas: needs, barriers and resources. All participants were asked to complete a hard copy of the survey at the meeting.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the distribution of sociodemographic characteristics, health behaviors, and cancer related information of the population. Values were imputed for the enhanced SCNS-SF that had ≤ 50% of the information missing within each domain using the Markov Chain Monte Carlo method, with the imputed value determined by the average of 5 imputations. Raw scores were standardized, taking the number of items in each domain into account. If m is the number of questions in the domain and k is the maximum value for each item (in this study k=5), the standardized score for each domain is obtained by calculating (total raw score–m)*100/(m*(k-1)), so the score range for each domain will be from 0 to 100. Therefore, the higher the score on the domain, the higher the perceived need is for support in that domain.

We constructed a multivariate linear regression model to evaluate differences in overall and domain specific needs across selected characteristics. Problems identified by survivors were dichotomized as present or absent and χ2 tests were used to evaluate univariate associations with selected characteristics. All p-values are two-sided and analyses were conducted using SPSS Version 10.

Results

A total of 6,235 print surveys were distributed and 1,164 were returned (19.0%). In addition, 429 surveys were completed online. Seventy-seven surveys were excluded for the following reasons: cancer diagnosis missing and 80% of survey incomplete (n=54), had not had cancer in lifetime (n=4), did not reside in Connecticut (n=16), and survey completed by proxy (n=3). After these exclusions, there were 1,516 evaluable surveys.

Participants were distributed throughout all eight Connecticut counties. Hartford (34.0%), New Haven (19.0%) and Fairfield (16.0%) counties had the largest proportion of participants. The majority (76.4%) of the 1,516 cancer survivors were female and the average age was 61 years (range 18-96) (Table I). The vast majority of participants were White (87.7%), followed by African American/Black (5.3%), and Hispanic/Latino (4.3%). Just over half of the participants had completed either a university/college or a professional/graduate degree (52.5%) and nearly two-thirds (62.3%) of the participants were either married or living as married. At the time of the survey, 49.7% were employed and 30.2% of participants reported individual income at or above the state’s median. Almost all of the participants had some health insurance coverage (98.6%), with 56% having private insurance.

Table I.

Selected characteristics of cancer survivors in needs assessment (N=1,516)

| Characteristic | Na | % |

|---|---|---|

| Female | 1150 | 76.4 |

| Age group | ||

| 18-49 | 264 | 17.5 |

| 50-64 | 662 | 44.0 |

| >=65 | 579 | 38.5 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White | 1322 | 87.7 |

| African American | 80 | 5.3 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 65 | 4.3 |

| Other | 40 | 2.7 |

| Education | ||

| Primary/Secondary | 366 | 24.3 |

| Some university/college | 349 | 23.2 |

| University/College degree or higher | 791 | 52.5 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married or marriage-like | 940 | 62.3 |

| Divorced or separated | 200 | 13.3 |

| Widowed | 192 | 12.7 |

| Single or never married | 177 | 11.7 |

| Employed | 735 | 49.7 |

| >=Connecticut median income level ($45,738) | 412 | 30.2 |

| Health insurance | ||

| Not covered | 21 | 1.4 |

| Medicaid only or Medicaid w/ private | 64 | 4.4 |

| Medicare only or Medicare and Medicaid | 208 | 14.1 |

| Private or other | 824 | 56.0 |

| Medicare w/ private or other | 354 | 24.1 |

| Ever smoker | 797 | 52.8 |

| Physical activity status | ||

| No physical activity | 149 | 11.5 |

| 1-10 times/month | 369 | 28.4 |

| 11-20 times/month | 285 | 21.9 |

| >20 times/month | 496 | 38.2 |

| Positive screening for depression | 323 | 24.5 |

| Lifetime self-report cancer typeb | ||

| Breast | 710 | 47.6 |

| Prostate | 146 | 9.8 |

| Colorectal | 87 | 5.8 |

| Lung | 80 | 5.4 |

| Melanoma | 79 | 5.3 |

| Time since diagnosis of most recent cancer | ||

| <=1 year | 445 | 30.3 |

| >1 to <=5 years | 526 | 35.8 |

| >5 years | 498 | 33.9 |

| Cancer free at the time taking the survey | 1139 | 77.4 |

| Lifetime cancer treatmentc | ||

| Surgery | 1121 | 75.4 |

| Chemotherapy | 800 | 53.8 |

| Radiation therapy | 818 | 55.1 |

| Hormonal therapy | 423 | 28.5 |

| Biological therapy | 108 | 7.3 |

| Bone marrow/peripheral blood cell transplant | 25 | 1.7 |

| No treatment | 25 | 1.7 |

May not sum to total due to missing data or selection of multiple choices.

Most common types. May fall in multiple categories if had more than one primary cancer.

Could select multiple answers.

The most prevalent lifetime cancer diagnosis was breast (47.6%), followed by prostate, colorectal, lung, and melanoma (all less than 10%) (Table I). The majority (77.4%) of the cancer survivors reported they were cancer free at the time of completing the survey. Approximately one-third (30.3%) of the participants were diagnosed with their most recent cancer within the last year, 35.8% were diagnosed between 1 and 5 years ago, and 33.9% were diagnosed more than 5 years ago. The vast majority of participants reported receiving treatment for their most recent cancer diagnosis, with surgery being the most common form of treatment (75.4%).

More than half (52.8%) of the survivors reported that they had smoked in their lifetime (Table I), with a mean of 19 years of smoking (data not shown). Physical activity more than 20 times per month, encompassing walking, jogging, participation in sports, walking to work or to the store and household chores, was reported by 38.2% of survivors. One-quarter (24.5%) of the participants answered yes to the one item depression screener.

Needs as assessed with the modified SCNF-SF34 were greatest in the psychological domain followed by the physical and daily living domain and then sexuality (Table II). With multivariate adjustment, overall need was statistically significantly greater among women (mean=25.3) than men (mean=22.3), with women reporting higher levels of need in each domain with the exception of sexuality (Table III). By ethnicity, Hispanic/Latino participants reported the highest level of need across the individual domains. With adjustment for other important characteristics, Hispanic/Latinos had statistically significant overall greater need than Whites and African Americans. Age was another important predictor of need, as need was highest among those diagnosed under age 50. Participants diagnosed within the last year reported overall greater needs, compared to those who were diagnosed 1-5 years ago, as well as to those whose cancer diagnosis was more than 5 years ago. We also found that difference in need were higher for those that were not cancer free at the time of taking the survey even after adjusting for other characteristics. Finally, we observed differenced by insurance status, with the lowest overall need among those with private insurance, and highest need among those with Medicare or Medicare with private insurance.

Table II.

Overall standardized scores by domain for the modified SCNS-SF (44 items)

| Domain | Number of Items in Survey |

Mean | SD | Median |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological | 11 | 31.13 | 27.19 | 25.00 |

| Health information and system | 13 | 23.88 | 23.13 | 23.08 |

| Physical and daily living | 5 | 27.61 | 28.35 | 20.00 |

| Patient and care support | 6 | 21.00 | 22.32 | 16.67 |

| Sexuality | 3 | 24.57 | 28.90 | 16.67 |

| Additional items | 6 | 22.38 | 22.54 | 20.83 |

| Overall needs – 44 items | 44 | 25.32 | 21.47 | 22.16 |

Table III.

Multivariate linear regression of mean scores of overall and domain specific needs on the modified SCNS-SF (44 items). Each characteristics adjusted for all other characteristics in the table.

| Characteristic | Psychological Mean Score |

Health System and Information Mean Score |

Physical and Daily Living Mean Score |

Patient Care and Support Mean Score |

Sexuality Mean Score |

Additional Items Mean Score |

Overall Needs Mean Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 27.7 | 20.5 | 21.3 | 18.6 | 28.3a | 19.6 | 22.3a |

| Female | 31.4 | 23.9 | 28.4 | 20.9 | 23.1a | 22.2 | 25.3a |

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| White | 30.1 | 22.6 | 26.3 | 19.7 | 24.6 | 20.8 | 24.1b |

| African American | 27.1 | 24.8 | 26.2 | 22.9 | 16.1 | 24.1 | 24.2b |

| Hispanic/Latino | 43.3 | 32.2 | 37.7 | 31.5 | 28.4 | 34.3 | 35.1b |

| Age | |||||||

| 18-49 years | 38.7 | 26.6 | 35.1 | 25.0 | 34.3 | 26.9 | 31.0a |

| 50-64 years | 35.0 | 25.3 | 30.4 | 22.2 | 29.2 | 25.0 | 27.8a |

| ≥ 65 years | 20.4 | 18.5 | 17.6 | 15.8 | 12.8 | 14.3 | 16.6a |

| Time since diagnosis | |||||||

| ≤ 1 year | 35.2 | 26.5 | 31.6 | 24.2 | 26.1 | 23.7 | 28.2a |

| 1-5 years | 30.2 | 23.1 | 26.9 | 19.7 | 25.4 | 22.4 | 24.5a |

| >5 years | 26.4 | 19.9 | 22.0 | 17.7 | 21.4 | 18.6 | 21.2a |

| Education | |||||||

| Primary/Secondary | 31.6 | 20.9 | 28.0 | 18.7 | 24.2 | 20.2 | 24.6c |

| Some College | 32.4 | 25.8 | 28.7 | 22.3 | 26.4 | 24.8 | 26.8c |

| ≥ College degree | 29.3 | 22.9 | 25.4 | 20.3 | 23.5 | 20.8 | 23.7c |

| Health insurance | |||||||

| Medicaid only or Medicaid w/ private | 45.1 | 36.9 | 40.5 | 32.8 | 37.2 | 35.4 | 37.3d |

| Medicare only or Medicare and Medicaid | 34.8 | 27.4 | 32.6 | 22.7 | 28.9 | 27.9 | 29.7d |

| Private or other | 26.4 | 20.1 | 22.9 | 17.7 | 21.0 | 17.7 | 20.9d |

| Medicare w/ private or other | 36.7 | 26.3 | 31.5 | 24.1 | 28.6 | 26.0 | 29.8d |

| Cancer free at survey | |||||||

| No | 39.5 | 28.6 | 36.7 | 26.1 | 26.5 | 27.7 | 30.9a |

| Yes | 28.2 | 21.7 | 24.1 | 18.9 | 23.8 | 20.0 | 23.0a |

Mean is significantly different from all other groups within characteristic at p<0.05.

Means for group 1 and group 2 are significantly different from group 3, but not from each other at p<0.05.

Means for group 2 and group 3 are significantly different from each other at p<0.05.

Means are significantly different from all other groups except for group 2 versus group 4 within characteristic at p<0.05.

For survivorship-related problems during the previous month, 42.3% of the survivors reported no problems. However, 3% of participants had experienced at least half of the 18 problems queried. Of the 57.7 % of survivors who reported at least one problem, the five most prevalent problems identified were weight gain/loss (35.4%), difficulty with memory (32.4%), paying for care (15.3%), communication (14.3%), and not being told about available services (12.0%) (Table IV).

Table IV.

Percentage of cancer survivors who experienced 18 commonly occurring problems/barriersa during the past month

| Problem | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Weight gain/loss | 460 (35.4) |

| Memory/Recall | 422 (32.4) |

| Pay for care/treatment | 200 (15.4) |

| Communication with provider (e.g. medical terminology) | 186 (14.3) |

| Not told about available services | 154 (12.0) |

| Transportation | 138 (10.5) |

| Complete excessive paperwork to receive services | 134 (10.3) |

| Follow-up care | 129 (10.0) |

| Needs of caregivers/family not met | 127 (9.9) |

| Obtaining medical records | 124 (9.5) |

| Obtaining medications | 107 (8.3) |

| Locating medical records | 85 (6.5) |

| Services inaccessible (e.g., too far) | 80 (6.2) |

| Child care/elder care | 61 (4.7) |

| Lack of respect or equal treatment | 61 (4.7) |

| Written materials in native language | 31 (2.4) |

| Language translation | 28 (2.2) |

| Compliance of treatment/other options with religious/personal belief | 28 (2.2) |

Could select multiple answers.

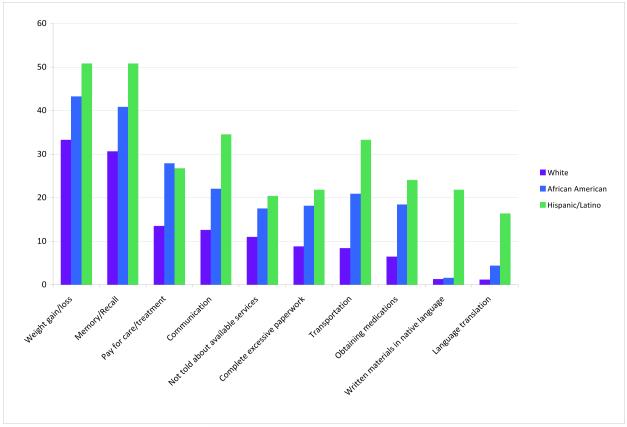

We evaluated differences in prevalence of these problems by selected characteristics (gender, age, race/ethnicity) in the univariate setting only. Women were more likely than men to report problems in the following areas: child/elder care (5.5% versus 2.3%, p=0.02), lack of respect or equal treatment (5.5% versus 2.3%, p=0.02), weight gain/loss (38.4% versus 25.7%, p=<0.001), and changes in memory (34.8% versus 25.2%, p=0.002) (data not shown). Hispanic/Latinos were more likely to report problems compared to both African Americans and Whites (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Statistically significant differences in problems/barriers encountered within the last month by ethnicity (White, African American, Hispanic/Latino). Limited to those problems reported by ≥ 15% of each group

We also observed some differences in the percentage of cancer survivors experiencing certain problems by age, with prevalence much higher in those 18-40 years old as compared to older survivors. (Table V).

Table V.

Statistically significant differences in the percentage of cancer survivors experiencing problems/barriers by age group

| Problem | Age Groups (years) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % of those 18-49 |

% of those 50-64 |

% of those ≥65 |

p-valuea | |

| Obtaining medications | 13.6 | 7.3 | 7.0 | 0.005 |

| Child care/elder care | 14.5 | 3.0 | 2.0 | <0.001 |

| Pay for care/treatment | 22.3 | 17.1 | 9.7 | <0.001 |

| Weight gain/loss | 47.2 | 36.8 | 27.4 | <0.001 |

| Memory/Recall | 43.8 | 34.4 | 24.1 | <0.001 |

| Needs of caregivers/family not met | 15.3 | 10.1 | 6.9 | 0.002 |

| Follow-up care | 15.0 | 9.3 | 8.0 | 0.011 |

For χ2 test.

The vast majority of participants cited medical sources (96.9%) as the primary information source regarding their most recent cancer, followed by non-medical sources (56.6%). Medical sources participants identified included primary care providers, oncologists, nurses, hospitals, and cancer centers and non-medical sources included other cancer survivors, cancer support groups, Internet, family and friends, and cancer organizations. The five most helpful sources of information participants reported were doctors (38.4%), Internet/books/media (18.7%), other healthcare providers/hospital staff (12.1%), family and friends (11.4%), and support groups (7.3%).

Qualitative Data from Community Forums

There were eight community forums with a total of 133 participants. Three of the forums were specific to the following minority populations: Native Americans, Hispanics/Latinos, Middle Easterns/Muslims. Themes which emerged from these discussions were similar to the overall survey results. Participants identified the need for information to manage treatment side effects and the need for improved communication with providers related to psychosocial issues. Barriers to survivorship care they identified were insurance coverage, transportation, and finances. Other cancer survivors, friends and family, and support groups were the most frequently reported resources for social support.

Discussion

In this population of cancer survivors in Connecticut, overall needs, as measured by the SCNS-SF were higher among women, younger survivors, those diagnosed within the past year, those not free of cancer at survey completion, and Hispanic/Latino. We also observed some differences by insurance status, with those with private insurance reporting lowest needs, and education status. Needs were highest in the psychological domain, which includes anxiety, depressed mood, fear of recurrence, and uncertainty about the future, across all participants regardless of gender, ethnicity, age, or time since diagnosis. The most prevalent problems/barriers encountered by this population of cancer survivors in the previous month were weight gain/loss, memory/recall, paying for care, communication, and not being told about services. There was a higher prevalence of most of the survivorship-related problems/barriers among the minority cancer survivors compared to Whites.

While this population of cancer survivors in Connecticut had greater level of need than those of cancer survivors in New South Wales, where the SCNS was first developed and used [16, 23, 24], there was a difference in time since diagnosis between the two populations. The majority of the New South Wales participants were more than five years post-diagnosis compared to the 64.8% of our sample who were less than five years since the time of their diagnosis. With 29.4% of our sample within one year since diagnosis, it is plausible that some were continuing in active treatment, which is known to be associated with greater needs [12]. However, a difference by time since diagnosis was present, even after adjusting for self-reported cancer free status at the time of the completing the survey, our best proxy variable for active treatment. Therefore, proximity to cancer diagnosis may impact overall need through other factors than treatment, such as psychological/psychosocial well-being. In a more recent study in England, with a sample within 6 months from completion of course of treatment, the reported needs were very similar to our findings [8]. In that study, fear of recurrence predicted unmet needs in all but the physical and sexual domains; hormone therapy use and negative mood were also predictive of unmet needs [8].

The end of treatment is a vulnerable time as patients transition away from active treatment and have less contact and support from providers [25, 26]. While quality of life gradually improves by the one-year mark, during the first year after treatment, many survivors experience persistent physical and psychological symptoms [19, 27]. The greatest areas of concern for survivors have been reported in the areas of psychological distress, specifically coping with fear of recurrence and need for psychological support [14-18], which is consistent with our findings. There is a recognized need for assessment, support and interventions to reduce psychological consequences of cancer and cancer treatment [1, 19, 28].

In the current population, problems related to care-giving responsibility (child or elder), paying for care, weight and memory changes, obtaining medication, and unmet needs of family/caregiver were most prevalent among survivors less than 50 years of age. Based on the SCNF, younger survivors also had higher overall need than their older counterparts. Poorer health related quality of life and greater physical and psychosocial needs have been consistently reported for younger cancer survivors [9, 10, 29, 30]. This finding is also supported by other study findings in which younger age was predictive of unmet need [14-18]. Studies among female cancer survivors have also found that younger women are more vulnerable and experience greater psychosocial needs, decreased functional status and lower quality of life compared to older women [14, 31, 32].

In our multivariate model, Hispanic/Latinos survivors reported significantly greater overall need than both Whites and African Americans. Furthermore, there were statistically significant differences in the number of problems reported by African Americans and Hispanics/Latinos in the areas of transportation, obtaining medications, communication, paying for care, not being well informed, and barriers to access to services, with Hispanics/Latinos most likely to experience these problems. In Connecticut, African American and Hispanics/Latinos are less educated and have lower incomes compared to Whites [33]. Although, socioeconomic status is one factor that may influence access to care and services for these ethnic minority survivors [34], differences in need persistent for Hispanics/Latinos with adjustment for education and health insurance, suggesting acculturation or language barriers may further contribute to unmet need in this group.

There are nearly three decades of research published on weight change related to cancer diagnosis and treatment, specifically weight gain among women with breast cancer. Women gain weight during or after systemic adjuvant therapy and the pattern of gain often continues [35-37]. In the present study, 46.8% of participants were breast cancer survivors and when we evaluated weight gain/loss by gender, this problem was more commonly reported by women (38.4%) than men (25.7%). There are little or no data on weight change in male cancer survivors, but our findings may indicate this as an area for further exploration. Unfortunately, these data cannot discriminate the direction of the change in weight.

Changes in cognitive function, often termed “chemo brain” in the lay literature have been well documented. While some studies have included males in the samples [38], the overwhelming number of studies have focused on women with breast cancer who received chemotherapy [39, 40], with some additional recent studies addressing the effects of endocrine therapy on cognitive function [41, 42]. In our population, 34.0% of women and 25.2% of male cancer survivors reported memory problems. Most cognitive function changes among cancer survivors have been associated with chemotherapy. However, as only 52.8% of the participants reported having received chemotherapy, this suggests the possible involvement of other factors (e.g., depression, work, stress) in this condition. In addition, while overall cognitive changes are also often associated with aging, only 50% of our sample were 60 years or older and interestingly, memory problems were more prevalent among the younger survivors.

This study was strengthened by the use of a validated instrument for assessing needs among cancer survivors. While this study examined the survivorship needs in a convenience sample, there was representation of various cancer types as well as all counties in the state of Connecticut. The level of needs among survey participants may have been lower than cancer survivors that did not participate, as this group of survivors by virtue of being willing to complete a survey, may be more actively engaged in utilizing resources and services to address their needs. Although we observed statistically significant differences in both need and problems by ethnicity, our sample had a relatively small proportion of ethnic minority cancer survivors. This lower percentage of cancer cases may partially be explained by the fact that ethnic minority populations in Connecticut tend to be younger than the White population. With this low participation, our sample may not be representative of all ethnic minority cancer survivors and these finding should be replicated in a larger population-based study. Since all information was self-reported and anonymous, we were unable to verify details provided by participants relating to cancer diagnosis and treatment, thus limiting our ability to examine cancer site and treatment specific trends. In addition, our sample likely included individuals both in and out of active treatment, which is likely to impact one’s level of need, and we did not specifically query if this was the case. Therefore, we had to rely on time since diagnosis and cancer-free status as proxies of treatment. Our sample was also relatively higher educated, so these results may not be generalizable to other populations in the US. However, the composition of our sample by race/ethnicity was not that dissimilar to Connecticut’s overall composition: 80% White, 9.4 % Black/African American, and 11.6% Hispanic [43]. Finally, the types of needs and problems assessed were limited to those included in the questionnaire, so we may have missed some areas of concern not included in the questionnaires. However, the SCNS-SF was developed in a oncology population and encompassed multiple need domains.

Overall, this needs assessment identified problem areas for targeting interventions across the Connecticut cancer survivor population. Since certain sub-groups have reported higher levels of need and were more likely to experience problems/barriers related to their illness, the Connecticut Cancer Partnership can work with individual providers, agencies, and cancer care centers to promote access and use of supportive services to these individuals, with specific attention to ethnic minority cancer survivors.

Acknowledgements

The statewide needs assessment of cancer survivors in Connecticut was commissioned by the Connecticut Department of Public Health based on recommendations from the Connecticut Cancer Partnership’s Survivorship Committee. MATRIX Public Health Solutions, Inc. was contracted to market, design, and distribute the needs assessment survey and analyze the data.

Funding Sources LMF was supported by grant T32 NR008346 from the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine . From cancer patient to cancer survivor: Lost in Transition. National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Krapcho M, Neyman N, Aminou R, Waldron W, Ruhl J, Howlader N, Tatalovich Z, Cho H, Mariotto A, Eisner MP, Lewis DR, Cronin K, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Stinchcomb DG, Edwards BK, editors. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2007, based on November 2009 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: 2010. Available from: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Program of Cancer Registries. Available from: http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/uscs/cancersbystateandregion.aspx.

- 4.Connecticut Department of Public Health Cancer Incidence in Connecticut. 2006 Available from: http://www.ct.gov/dph/cwp/view.asp?a=3129&q=389716&dphPNavCtr=∣47825∣#47827.

- 5.American Cancer Society . Cancer Facts and Figures 2009. American Cancer Society; Atlanta: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Connecticut Tumor Registry Connecticut Tumor Registry Cancer Inquiry System. Available from: http://www.cancer-rates.info/ct/

- 7.Hewitt ME, Bamundo A, Day R, Harvey C. Perspectives on post-treatment cancer care: qualitative research with survivors, nurses, and physicians. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(16):2270–3. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.0826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Armes J, Crowe M, Colbourne L, Morgan H, Murrells T, Oakley C, et al. Patients’ supportive care needs beyond the end of cancer treatment: a prospective, longitudinal survey. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(36):6172–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.5151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McInnes DK, Cleary PD, Stein KD, Ding L, Mehta CC, Ayanian JZ. Perceptions of cancer-related information among cancer survivors: a report from the American Cancer Society’s Studies of Cancer Survivors. Cancer. 2008;113(6):1471–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beckjord EB, Arora NK, McLaughlin W, Oakley-Girvan I, Hamilton AS, Hesse BW. Health-related information needs in a large and diverse sample of adult cancer survivors: implications for cancer care. J Cancer Surviv. 2008;2(3):179–89. doi: 10.1007/s11764-008-0055-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stein KD, Syrjala KL, Andrykowski MA. Physical and psychological long-term and late effects of cancer. Cancer. 2008;112(11 Suppl):2577–92. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harrison JD, Young JM, Price MA, Butow PN, Solomon MJ. What are the unmet supportive care needs of people with cancer? A systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0615-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aziz N. Late effects of cancer treatment. In: Ganz PA, editor. Cancer Survivorship. Springer Publishers; New York: 2007. pp. 54–76. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thewes B, Butow P, Girgis A, Pendlebury S. The psychosocial needs of breast cancer survivors; a qualitative study of the shared and unique needs of younger versus older survivors. Psychooncology. 2004;13(3):177–89. doi: 10.1002/pon.710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hodgkinson K, Butow P, Hunt GE, Pendlebury S, Hobbs KM, Wain G. Breast cancer survivors’ supportive care needs 2-10 years after diagnosis. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15(5):515–23. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0170-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanson-Fisher R, Girgis A, Boyes A, Bonevski B, Burton L, Cook P. The unmet supportive care needs of patients with cancer. Supportive Care Review Group. Cancer. 2000;88(1):226–37. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(20000101)88:1<226::aid-cncr30>3.3.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lintz K, Moynihan C, Steginga S, Norman A, Eeles R, Huddart R, et al. Prostate cancer patients’ support and psychological care needs: Survey from a non-surgical oncology clinic. Psychooncology. 2003;12(8):769–83. doi: 10.1002/pon.702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hwang SY, Park BW. The perceived care needs of breast cancer patients in Korea. Yonsei Med J. 2006;47(4):524–33. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2006.47.4.524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Institute of Medicine . Cancer care for the whole patient: Meeting psychosocial health needs. National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Newell S, Sanson-Fisher RW, Girgis A, Ackland S. The physical and psycho-social experiences of patients attending an outpatient medical oncology department: a cross-sectional study. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 1999;8(2):73–82. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2354.1999.00125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Screening for Depression in Adults, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Available from: http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspsaddepr.htm. [PubMed]

- 22.Boyes A, Girgis A, Lecathelinais C. Brief assessment of adult cancer patients’ perceived needs: development and validation of the 34-item Supportive Care Needs Survey (SCNS-SF34) J Eval Clin Pract. 2009;15(4):602–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2008.01057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bonevski B, Sanson-Fisher R, Girgis A, Burton L, Cook P, Boyes A. Evaluation of an instrument to assess the needs of patients with cancer. Supportive Care Review Group. Cancer. 2000;88(1):217–25. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(20000101)88:1<217::aid-cncr29>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boyes A, Zucca A, Lecathelinais C, Girgis A. Supportive Care Needs Survey: Supplement 1A: Long-term cancer survivors reference data. Center for Health Research and Psycho-oncology; Newcastle: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lethbord C, Kissane D. It Doesn’t End on the Last Day of Treatment” A Psychoeducational Intervention for Women After Adjuvant Treatment for Early Stage Breast Cancer. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2003;21(3):25–41. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lethborg C, Kissane D, Burns W, Synder R. “Cast Adrift” The Experience of Completing Treatment Among Women with Early Stage Breast Cancer. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2000;18(4):73–90. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Knobf MT. Symptom distress before, during and after adjuvant breast therapy. Dev Support Cancer Care. 2000;4:13–17. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fuerstein M. Handbook of Cancer Survivorship. Springer; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Absolom K, Eiser C, Michel G, Walters SJ, Hancock BW, Coleman RE, et al. Follow-up care for cancer survivors: views of the younger adult. Br J Cancer. 2009;101(4):561–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baker F, Denniston M, Smith T, West MM. Adult cancer survivors: how are they faring? Cancer. 2005;104(11 Suppl):2565–76. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kroenke CH, Rosner B, Chen WY, Kawachi I, Colditz GA, Holmes MD. Functional impact of breast cancer by age at diagnosis. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(10):1849–56. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.04.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Avis NE, Crawford S, Manuel J. Quality of life among younger women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(15):3322–30. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.The Connecticut Health Disparities Project . The 2009 Connecticut Health Disparties Report. Connecticut Department of Public Health; Hartford: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clegg LX, Reichman ME, Miller BA, Hankey BF, Singh GK, Lin YD, et al. Impact of socioeconomic status on cancer incidence and stage at diagnosis: selected findings from the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results: National Longitudinal Mortality Study. Cancer Causes Control. 2009;20(4):417–35. doi: 10.1007/s10552-008-9256-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McInnes JA, Knobf MT. Weight gain and quality of life in women treated with adjuvant chemotherapy for early-stage breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2001;28(4):675–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kroenke CH, Chen WY, Rosner B, Holmes MD. Weight, weight gain, and survival after breast cancer diagnosis. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(7):1370–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saquib N, Flatt SW, Natarajan L, Thomson CA, Bardwell WA, Caan B, et al. Weight gain and recovery of pre-cancer weight after breast cancer treatments: evidence from the women’s healthy eating and living (WHEL) study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;105(2):177–86. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9442-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jansen CE, Miaskowski C, Dodd M, Dowling G, Kramer J. A metaanalysis of studies of the effects of cancer chemotherapy on various domains of cognitive function. Cancer. 2005;104(10):2222–33. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stewart A, Bielajew C, Collins B, Parkinson M, Tomiak E. A meta-analysis of the neuropsychological effects of adjuvant chemotherapy treatment in women treated for breast cancer. Clin Neuropsychol. 2006;20(1):76–89. doi: 10.1080/138540491005875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Falleti MG, Sanfilippo A, Maruff P, Weih L, Phillips KA. The nature and severity of cognitive impairment associated with adjuvant chemotherapy in women with breast cancer: a meta-analysis of the current literature. Brain Cogn. 2005;59(1):60–70. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bender CM, Sereika SM, Brufsky AM, Ryan CM, Vogel VG, Rastogi P, et al. Memory impairments with adjuvant anastrozole versus tamoxifen in women with early-stage breast cancer. Menopause. 2007;14(6):995–8. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e318148b28b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Palmer JL, Trotter T, Joy AA, Carlson LE. Cognitive effects of Tamoxifen in pre-menopausal women with breast cancer compared to healthy controls. J Cancer Surviv. 2008;2(4):275–82. doi: 10.1007/s11764-008-0070-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.US Census Bureau [Accessed 5/31/11];Fact Sheet for Connecticut. http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/ACSSAFFFacts?_event=Search&geo_id=01000US&_geoContext=01000US&_street=&_county=&_cityTown=&_state=04000US09&_zip=&_lang=en&_sse=on&ActiveGeoDiv=geoSelect&_useEV=&pctxt=fph&pgsl=010&_submenuId=factsheet_1&ds_name=ACS_2009_5YR_SAFF&_ci_nbr=null&qr_name=null®=null%3Anull&_keyword=&_industry.