Abstract

The present study evaluated cerebrovascular disease (CVD), β-amyloid (Aβ), and cognition in clinically normal elderly adults. Fifty-four participants underwent MRI, PIB-PET imaging, and neuropsychological evaluation. High white matter hyperintensity burden and/or presence of infarct defined CVD status (CVD−: N = 27; CVD+: N = 27). PIB-PET ratios of Aβ deposition were extracted using Logan plotting (cerebellar reference). Presence of high levels of Aβ in prespecified regions determined PIB status (PIB−: N = 33; PIB+: N = 21). Executive functioning and episodic memory were measured using composite scales. CVD and Aβ, defined as dichotomous or continuous variables, were unrelated to one another. CVD+ participants showed lower executive functioning (P = 0.001) when compared to CVD− individuals. Neither PIB status nor amount of Aβ affected cognition (Ps ≥ .45), and there was no statistical interaction between CVD and PIB on either cognitive measure. Within this spectrum of normal aging CVD and Aβ aggregation appear to be independent processes with CVD primarily affecting cognition.

Keywords: PIB, cerebrovascular disease, episodic memory, executive functioning, cognition

Introduction

Aβ plaques are a hallmark feature of Alzheimer’s Disease (AD), however post mortem studies show that they also frequently exist in the absence of clinical dementia (Bennett et al., 2006; Crystal et al., 1993; Esiri and Wilcock, 1986; Knopman et al., 2003; Tomlinson et al., 1968). The recent introduction of a PET radiotracer that binds to fibrillar Aβ, Pittsburg Compound B (PIB, Klunk et al., 2004), has further supported the pathology findings by revealing increased PIB binding in a large proportion of non-demented elderly (Mintun et al., 2006; Rowe et al., 2007). Cross-sectional studies examining the relation of Aβ with cognition have been equivocal, with deficits in episodic memory found in some postmortem and imaging studies (Bennett et al., 2006; Pike et al., 2007), but not others (Aizenstein et al., 2008). Longitudinal observation of amyloid aggregation using PIB-PET imaging has shown that individuals with greater baseline levels of Aβ show episodic memory decline at a steeper rate (Resnick et al., 2010) and are at increased risk of developing AD (Morris et al., 2009; Villemagne et al., 2011). Therefore, if cognitive deficits are associated with Aβ, they are likely to be mild and may be due to downstream effects of this deposition as proposed by Jack et al. (2009) in a hypothetical model of AD progression.

Cerebrovascular health and cerebrovascular disease (CVD) is another important contributor to age-related cognitive decline. Fifteen to 46 percent of older non-demented adults have evidence of cerebral infarction at autopsy (Bennett et al., 2006; Knopman et al., 2003; Neuropathology Group, 2001), and clinically silent infarcts are frequently observed in neuroimaging studies (Bernick et al., 2001; Decarli et al., 2005). It is well established that large vessel damage can cause severe cognitive disability and increase the risk of dementia (Henon et al., 2001; Pendlebury and Rothwell, 2009) and recent attention has focused on the impact of cerebral small vessel disease on cognition, such as white matter damage and subcortical vascular lesions. Whether cerebral small vessel disease contributes to cognitive decline is still under debate (eg Mungas et al., 2001); however lacunar infarcts may impair both general cognition (van der Flier et al., 2005) -- executive functioning specifically (Benisty et al., 2009; Carey et al., 2008; Reed et al., 2004) – and cause dementia (Lee et al., 2011). Focal and diffuse lesions in the white matter, seen as hyperintensities on T2-weighted MRI images (white matter hyperintensities, WMH) are the most ubiquitous age-related alteration seen in the brain (Neuropathology Group, 2001). While the etiologies of WMH are diverse, in elderly populations WMH are associated with vascular risk factors (eg hypertension and atherosclerosis) (Jeerakathil et al., 2004; Wahlund et al., 2009) and an increased risk for stroke, dementia and death (Debette et al., 2010), indicating that, in the elderly, they likely reflect vascular brain injury. WMH volume has been associated with worse cognition in a number of domains, particularly in executive functioning tasks reliant on the frontal lobe (Brickman et al., 2009; Bunce et al., 2010; DeCarli et al., 1995; He et al., 2010; Prins et al., 2005; Tullberg et al., 2004).

CVD and Aβ frequently co-occur in dementia (Esiri et al., 1999; Gold et al., 2007; Schneider et al., 2007), and there has been increasing data to suggest that this may not be coincidental. Disruption of the vascular system may promote Aβ aggregation (Zhang et al., 2007), restrict clearance of Aβ (Hachinski and Munoz, 1997), or conversely be caused by vascular Aβ (Han et al., 2008). Regardless of the specific mechanism, these studies point to a relationship between CVD and Aβ. This relationship is supported by epidemiological evidence that risk factors for vascular disease also predispose to clinically diagnosed AD (Breteler, 2000; Mielke et al., 2007; Skoog et al., 1999). An alternative explanation for the frequent coexistence of vascular disease and Aβ in dementia suggests that CVD simply lowers the threshold for cognitive decline and AD symptomology (Newman et al., 2005; Riekse et al., 2004; Snowdon et al., 1997) rather than promoting Aβ aggregation.

PIB-PET combined with MRI imaging of vascular brain injury allows us to directly identify the separate and combined effects of CVD and Aβ plaques on cognitive performance, namely executive functioning and episodic memory, in cognitively normal older adults. We specifically explored whether: 1. Individuals with CVD show decreased executive functioning; 2. Aβ deposition alone affects cognition; 3. Executive functioning and/or episodic memory are most impaired when both Aβ and CVD are present. 4. Additionally, we examined whether there is greater Aβ accumulation in individuals with CVD, and if so whether this relationship exists along a continuum or becomes apparent when Aβ deposition reaches a level indicative of significant pathology. This investigation focused on cognitively normal individuals as the amount of pathology from both diseases is likely to be mild and pathological studies suggest that the impact on future dementia is likely to be nearly equal (Schneider et al., 2004).

METHODS

Participants

Clinically normal participants were pooled from two independent cohorts, each investigating age-associated alterations in cognition, and brain structure and function. Thirty participants from the Aging Brain project (mean age 77.1 ± 7.6 years) and 24 participants from the Berkeley Aging Cohort (BAC; mean age 77.0 ± 5.5) underwent cognitive testing, PIB-PET and MRI scanning. The mean time between MRI and PIB was 1.96 ± 3.66 months; between MRI and Cognitive testing was 2.67 ± 3.01 months; and between PIB and Cognitive testing = 3.37 ± 2.84 months; with an interval of 0 to 17 months for all sessions.

The Aging Brain project is an ongoing multi-site program previously described in detail (Reed et al., 2007) with a focus on vascular contributions to cognitive decline and dementia. The project enrolls individuals aged 55 years or older with cognitive ability ranging between normal and mild dementia who have variable degrees of vascular risk. Participants are excluded if they have been diagnosed with a neurodegenerative illness separate from AD or vascular dementia, have a history of psychiatric illness or substance abuse within five years prior to enrollment or five years preceding the onset of cognitive symptoms, or have significant head injury or unstable major medical illness. All participants included in the present study were non-demented with a Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) = 0; 27 of whom were also studied in the companion Reed et al. article in this issue.

BAC participants are aged 60 years or older, living independently, with normal cognitive test performance (Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE) ≥ 25, Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) ≤ 10, age and education adjusted California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT) ≥ 1.5 SDs above the mean BAC score), and no evidence of any major medical, neurological or psychiatric illness that impacts cognition. The 24 participants recruited for the present study were selected to resemble the demographic characteristics of participants from the Aging Brain project.

The study was approved by the institutional review boards at all participating institutions. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants following IRB-approved protocols.

Vascular Risk

Medical history or self-report of heart disease, diabetes, hypertension (including use of antihypertensive medication), high cholesterol (including use of lipid-lowering medication), and smoking status were recorded. Each category was designated a number reflecting presence (1) or absence (0) of the risk factor. A composite measure of vascular risk was created from the average of these factors. One participant did not have data for heart disease, and one participant did not have cholesterol information; the average of the remaining data was recorded for these participants. Vascular risk information was not obtained from one participant.

Cognitive Testing

The MMSE was used as a measure of global cognitive functioning and the GDS as a measure of depressive symptoms.

Executive Functioning

Cognitive tasks of executive functioning included Trail Making Task A and B, phonemic (FAS) and semantic (animals) fluency, and Digit Span Forward and Backward. These tests were selected based on a priori evidence that they reflect frontal/executive function and because all participants in both cohorts were tested with these measures.

Executive functioning measures were Z-transformed using the mean and standard deviations from 296 cognitively intact participants from both the BAC and Aging Brain cohorts not included in the present study (mean age = 73.9, SD = 8.7; mean education = 16.9, SD = 2.3; mean MMSE = 28.7, SD = 1.5). Trail Making completion time scores were inverted to reflect that lower values indicate better performance. Z scores were averaged to create a composite executive functioning (EXECUTIVE) measure. For participants missing data from any of the cognitive tasks a Z- score average was calculated from the tasks completed.

Episodic Memory

The episodic memory measure (MEMORY) was generated from the CVLT (Delis et al., 1987) for the BAC cohort and the Memory Assessment Scales list learning subtest (MAS; Williams, 1991) for the Aging Brain cohort. These tests were selected because of their comparable instructions, procedure and performance requirements. CVLT norms were created from the most recent testing session for BAC participants aged 55 years or older (N = 240; excluding participants used in the present study). The sum of trials 1 through 5, and the sum of short delay free recall, short delay cued recall, long delay free recall and long delay cued recall trials were Z transformed, then averaged to create a composite MEMORY measure.

MAS norms were generated from cognitively intact Aging Brain participants not included in the present study (CDR = 0; N = 55). The sum of learning trials 1 through 6, and the sum of short delay free recall, short delay cued recall, long delay free recall and long delay cued recall trials were Z transformed, then averaged to create a composite MEMORY measure. Nine participants did not receive assessments of memory.

MR Imaging

Acquisition

Structural MRI scans for the BAC participants were collected at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL) on a 1.5 T Magnetom Avanto System with a 12 channel head coil run in triple mode. Each MRI session included a high-resolution T1-weighted volumetric magnetization prepared rapid gradient echo scan (MP-RAGE; TR = 2110, TE = 3.58, TI = 1100, with 1 mm3 isotropic resolution) and a fluid-attenuated inversion recovery scan (FLAIR, TR = 9730, TE =100, TI = 2500, with 0.75 × 0.75 mm2 in-plane resolution and 3.00 mm slice thickness).

Structural MRI scans for participants from the Aging Brain study were collected on three MRI systems. Twenty-two participants were scanned at the University of California, Davis research center using a 3 T Siemens Magnetom Trio Syngo System with an 8 channel head coil. Acquired images included a T1-weighted volumetric MP-RAGE (TR = 2500, TE = 2.94 or 2.98, T1= 1100, with 1 mm3 isotropic resolution) and a FLAIR scan (TR = 5000, TE = 403, TI = 1700, with 1.00 × 1.00 mm2 in-plane resolution and 2.00 mm slice thickness). Seven participants received scans using a 1.5 T GE Signa Genesis system at the University of California, Davis research center. Each session included a T1-weighted 3D spoiled gradient recalled echo scan (SPGR, TR = 9, TE = 1.9, with 0.98 × 0.98 mm2 in-plane resolution and 1.5 mm slice thickness), and a FLAIR scan (TR = 11002, TE = 147, TI = 2250, with 0.98 × 0.98 mm2 in-plane resolution and 3.00 mm slice thickness). One participant was scanned at the San Francisco Veterans Administration Hospital using a 4 T Siemens MedSpec Syngo System with an 8 channel head coil. A T1-weighted volumetric MP-RAGE scan (TR = 2300, TE = 3.37, TI = 950, with 1 mm3 isotropic resolution) and a FLAIR scan (TR = 6000, TE = 405, TI = 2050, with 1 mm3 isotropic resolution) were acquired.

Given the difference in MRI acquisition protocols, the T1-weighted MRI images were only used to identify infarcts and to assist with PIB-PET processing.

White Matter Hyperintensity Quantification

FLAIR images were segmented using a semi-automated procedure previously described elsewhere (DeCarli et al., 1992; Yoshita et al., 2005). In brief, CSF and brain matter were assumed to have separate, but possibly overlapping, population distributions of pixel intensities. After correcting for image intensity inhomogeneity (DeCarli et al., 1996), these distributions were modeled using Gaussian functions, with the segmentation threshold determined by the intersection of the CSF modeled distribution with the brain matter modeled distribution. Following this initial segmentation, the brain-only FLAIR pixel intensity histogram was modeled as a Gaussian distribution, and pixel intensities 3.5 SDs above the mean were classified as WMH. Total cranial volume, total brain volume, total CSF volume, and WMH volume were quantified. WMH volume was divided by total cranial volume to yield the WMH percentage used in this analysis.

CVD positivity

Infarcts were identified by an experienced neurologist (WJJ) blind to any other participant data using the T1-weighted and FLAIR MRI images. Presence of infarct was analyzed on a yes/no basis. Lacunes were defined as discrete subcortical lesions greater than 2mm in diameter seen as hypointense on the T1 image. Cortical infarcts were hypointense on T1 images spanning vascular territories. They were categorized into cortical and subcortical subtypes primarily to account for potential influence of cortical infarct on cognitive performance and secondarily to explore whether cortical versus subcortical infarct location was differentially associated with PIB binding. Participants with WMH greater than .5% of total intracranial volume (following DeCarli et al.’s (1995) definition of significant WMH pathology) and/or presence of infarct were classified as CVD positive.

PET Imaging

Acquisition

The PIB radiotracer was synthesized at LBNL using a previously published protocol (Mathis et al., 2003) and PIB-PET imaging was conducted using a Siemens ECAT EXACT HR PET scanner in 3D acquisition mode. 10-15 mCi of PIB was injected as a bolus into an antecubital vein. Dynamic acquisition frames were obtained for a total of 90 minutes: 4 × 15 sec, 8 × 30 sec, 9 × 60 sec, 2 × 180 sec, 8 × 300 sec, 3 × 600sec.

Image Analysis

PIB data were preprocessed using Statistical Parametric Mapping 8 (SPM8; http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/). Frames 6 through 34 were realigned to frame 17, and averaged to create a mean frame. The first five frames were summed and coregistered to the mean frame, with the coregistration parameters applied to these individual five frames. The coregistered frames reflecting the first 20 minutes of acquisition (frames 1-23) were then averaged to create a new image, which was used to guide coregistration of the T1-weighted MRI. Distribution volume ratio (DVR) images were generated from PIB frames corresponding to 35-90 min post-injection. The FreeSurfer software package version 4.5.0 (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/) was used to generate a cerebellar grey matter mask from each participant’s T1 MRI following procedures previously described (Mormino et al., 2009). The cerebellar mask served as a reference region for PIB processing, and each participant’s mask was manually edited to remove non-cerebellar tissue. DVRs were quantified using Logan graphical analysis and the participant’s grey matter cerebellar reference region (Logan et al., 1996; Price et al., 2005).

The T1-weighted MRI was warped to MNI space using the SPM T1 template, and the warp parameters were applied to the coregistered PIB DVR image. Cerebellar ROI registration and warped images were visually inspected to ensure alignment.

Regions of interest (ROIs) were defined in MNI space using the Automated Anatomic Labeling Atlas (Tzourio-Mazoyer et al., 2002). In order to minimize contamination from white matter and cerebrospinal fluid, ROIs were trimmed using a grey matter mask defined by each participant’s segmented MRI (Sun et al., 2007). DVR values were extracted from ROIs vulnerable to early Aβ deposition, which include the frontal cortex (anterior to the precentral gyrus), lateral parietal cortex, lateral temporal cortex, posterior cingulate, and precuneus (Mormino et al., 2009; Rabinovici et al., 2010). A global measure of PIB uptake (Global PIB Index) was generated from the mean DVR of these ROIs. The occipital cortex was also examined due to its susceptibility to cerebral amyloid angiopathy. ROIs that overlapped with the infarct and peri-infarct regions in the three individuals with cortical infarct were manually edited so that DVR values excluded these regions.

PIB positivity

In order to define PIB as a dichotomous variable, eleven young adults (mean age = 24.5, SD = 3.4) underwent PIB-PET imaging using the same acquisition and processing procedures described above. PIB uptake was determined using DVR values from the Global PIB Index and the bilateral precuneus/posterior cingulate region (an area most often and earliest affected by amyloid aggregation in AD). An average DVR was created for each of these ROIs, and values 2 SDs above each average were established as defining values of PIB positivity. Therefore participants with a global PIB index > 1.114 or precuneus/posterior cingulate > 1.137 were determined to be PIB positive (N = 21). Most who were positive in either region were positive in both regions (N = 17).

Statistical Models

All analyses were conducted using PASW Statistics software (version 18.0). Differences between dichotomous variables were assessed using Pearson Chi-squared tests. Group differences for participant characteristics were assessed using independent sample t-tests or Mann Whitney tests when variances were not equal between groups. Continuous variables and interactions were initially assessed using independent measures analysis of variance (ANOVA); however final statistics were reported using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) where age and gender were controlled; and age, gender, and education were controlled in analyses of cognition. Stepwise linear regressions that included age, gender (and education where appropriate) in the first step were used to assess relationships between continuous variables. An alpha level of 0.05, two tailed, was used to determine statistical significance.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Demographics, APOE status, vascular measures, and PIB status of participants are summarized in the table, stratified by CVD status. CVD negative (N = 27) and CVD positive (N = 27) participants did not differ in age, sex, education, APOE status or GDS. CVD positive participants performed worse on the MMSE (t(51) = 2.32, P = 0.02), and had higher vascular risk (t(51) = 2.42, P = 0.02). Eighteen participants had at least one infarct, with an average of 1.67 infarcts (SD = 0.91, range: 1-4). Fifteen participants only had subcortical infarct(s), all of which were lacunar. Three individuals had cortical infarct, two of whom also had a subcortical infarct. Participants with infarct had significantly higher WMH values (U = 206, P = 0.03) and a greater composite vascular risk (t(51) = 3.45, P = 0.001) than those without infarct. Twelve individuals with MRI-identified infarct also had a clinical history of stroke, 6 had no history of stroke, and 2 individuals had a clinical history of stroke with no infarct identified on MRI. WMH volume did not differ based on MRI field strength (F(2,51) = 0.31, P = 0.73). PIB negative (N = 33) and PIB positive (N = 21) participants did not differ in age, sex, MMSE, GDS or vascular risk. PIB positive participants had significantly lower education (t(52) = 2.32, P = 0.02) and a trend towards increased likelihood of carrying the APOE ε4 allele (χ2 = 3.65, P = 0.056).

A significantly larger proportion of participants from the Aging Brain study were CVD positive (70%) compared with BAC participants (25%; χ2 = 10.8, P = 0.001), presumably due to the vascular focus of the Aging Brain project. Although Aging Brain participants had a somewhat higher prevalence of PIB positivity, the differences were not significant (Aging Brain: 46.7%, BAC: 29.2%; (χ2 = 1.72, P = 0.19).

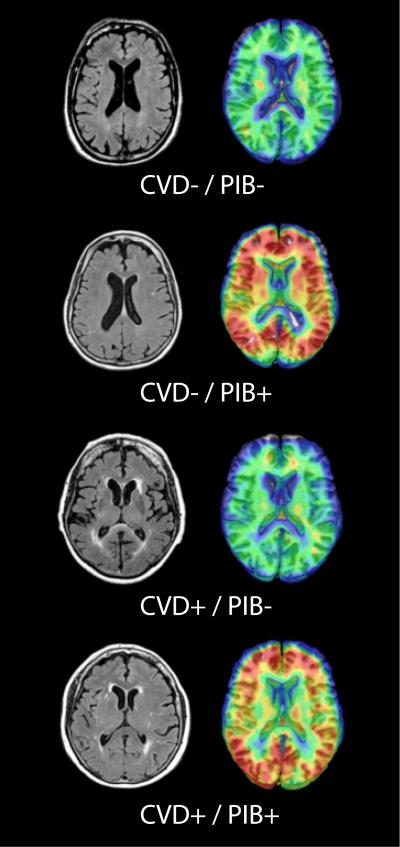

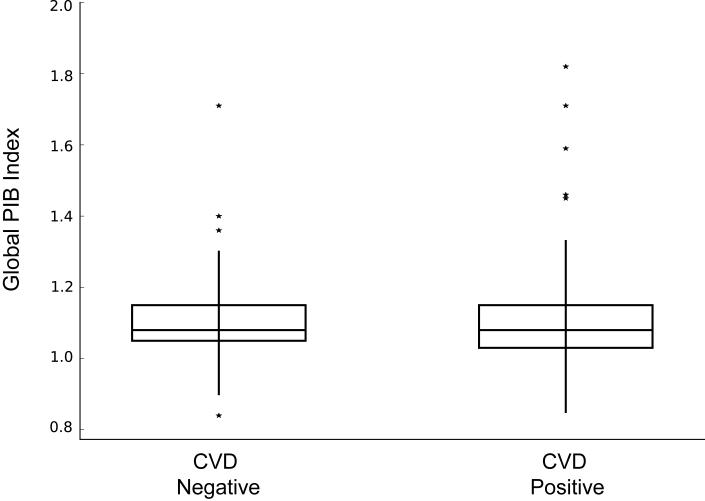

Vascular Relationship with PIB Indices

CVD status was independent of PIB status (χ2 = 0.7, P = 0.4, Table). Fig. 1 provides images of participants in each of the four categories of brain pathology by CVD and PIB classification. There was no difference between CVD positive and CVD negative participants in any of the individual ROIs comprising the Global PIB Index or the occipital lobe when examining PIB DVR values as a continuous variable. Fig. 2 shows Global PIB Index DVR values for CVD positive and CVD negative participants.

Table.

Participant characteristics (mean ± standard deviation) stratified by cerebrovascular disease (CVD) status.

| CVD − (N = 27) |

CVD + (N = 27) |

TOTAL (N = 54) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 76.2 ± 6.4 | 77.8 ± 7 | 77 ± 6.7 |

| Sex (M/F) | 14 / 13 | 18 / 9 | 32 / 22 |

| Education | 16.2 ± 2.6 | 14.8 ± 2.9 | 15.5 ± 2.8 |

| APOE ε4 %° | 23.1% | 28% | 25.5% |

| GDS | 4 ± 3.7 | 2.4 ± 2.2 | 3.2 ± 3.2 |

| MMSE | 29.1 ± 1.2 | 28.3 ± 1. 2* | 28.7 ± 1.3 |

| Composite Vascular Risk | .27 ± .27 | .44 ± .27* | .36 ± .27 |

| WMH percentage of TCV | .19 ± .11 | .92 ± .75** | .56 ± .65 |

| Infarct Type (Cortical/Subcortical/ Both) |

0 | 1 / 14 / 2 | 1 / 14 / 2 |

| PIB − /+ | 18 / 9 | 15 / 12 | 33 / 21 |

P< 0.05,

P < 0.001,

1 CVD− and 2 CVD+ participants were not tested for APOE.

APOE ε4 carriers (%) = percentage of individuals with at least one apolipoproteinE ε4 allele. GDS = Geriatric Depression Scale. MMSE = Mini Mental State Examination. Composite Vascular Risk = average of five CVD risk factors: heart disease, diabetes, hypertension, high cholesterol, and current smoking status. WMH = white matter hyperintensity volume. TCV = total cranial volume.

Figure 1. Representative brain images from the four categories of brain pathology.

Presence of infarct or WMH volume > .5% of total intracranial volume defined CVD positivity. DVR values of Global PIB Index > 1.114 or bilateral precuneus/posterior cingulate region > 1.137 defined PIB positivity.

Figure 2. Box and whiskers plot of mean Global PIB Index volume based on CVD(+/−) status.

CVD− and CVD+ groups did not differ in Global PIB Index DVR values.

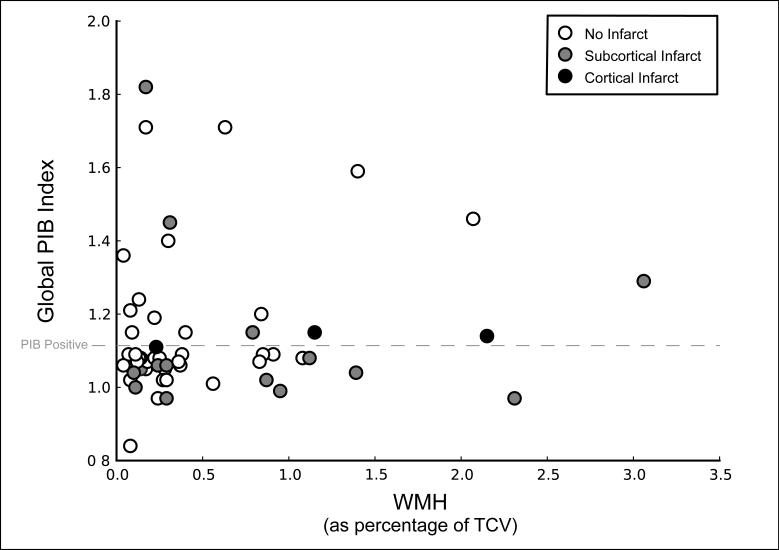

Linear regression was used to determine whether a continuous relationship existed between WMH and PIB uptake, regressing Global PIB Index against WMH. WMH was not correlated with Global PIB Index (Fig. 3). There was also no relationship between infarct status and PIB when PIB was treated as a continuous (PIB Global Index; F(1,50) = 0.09, P = 0.76) or a categorical variable (χ2 = 0.35, P = 0.55); however, all three individuals with cortical infarct were classified as PIB positive (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Scatterplot of continuous measures of Global PIB Index volume and white matter hyperintensity volume (reported as percentage of total cranial volume).

Open circles represent individuals with no infarct, grey circles represent subcortical infarct and black circles represent cortical infarct (2 individuals with cortical infarct also had subcortical infarcts). Global PIB Index volume was not related to WMH volume or infarct status. Categorizing Global PIB Index into a dichotomous variable (PIB+/−, based on a cutoff of 2 SD above a young control group), demonstrated by the dashed line, further supported the absence of a relationship between PIB and WMH or infarct; although all individuals with cortical infarct were PIB+. Three individuals were classified as PIB+ due to significant PIB deposition in bilateral precuneus/posterior cingulate region, they are not represented as PIB+ in the present graph.

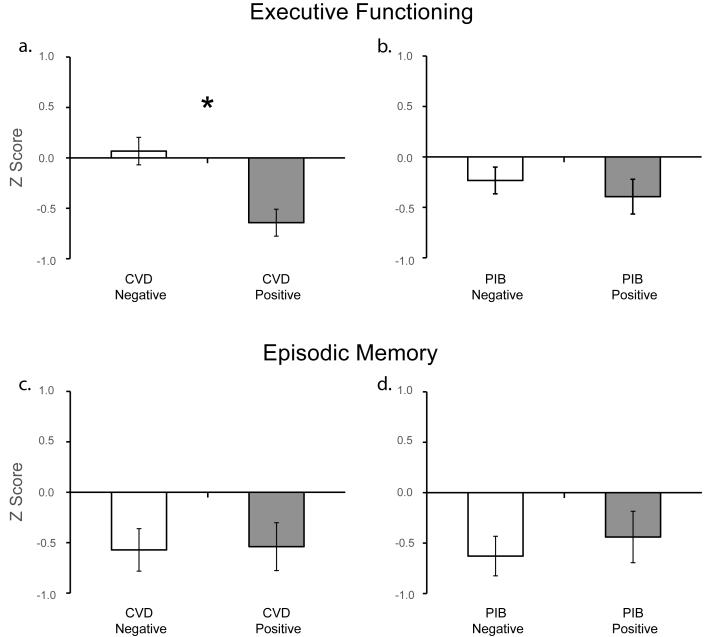

Executive Functioning

CVD positive participants performed significantly worse than CVD negative participants on the EXECUTIVE composite measure (F(1,48) = 12.88, P = 0.001; Fig. 4a). To examine whether this effect was driven by individuals with cortical infarct, excluding the three individuals with cortical infarct did not alter this finding (F(1,45) = 10.13, P = 0.003). A linear regression was used to determine whether a continuous relationship existed between WMH and EXECUTIVE, regressing EXECUTIVE on WMH. In a model with age and gender, WMH was negatively correlated with EXECUTIVE (ΔR2 = 0.1, t = −2.37, P = 0.02); when education was added to the model, WMH was significant at a trend level (ΔR2 = 0.05, t = −1.81, P = 0.08). Individuals with infarct had significantly worse EXECUTIVE than those without infarct (F(1,48) = 15.85, P < 0.001); this relationship remained after excluding the three individuals with cortical infarct (F(1,45) = 10.4, P = 0.002).

Figure 4. Executive functioning and episodic memory stratified by CVD(+/−) and PIB(+/−) status.

Cognitive performance measures (corrected for age, sex, and education) are represented as Z-scores. a. CVD+ participants show significantly worse executive functioning than CVD− participants (P = 0.001; corrected for age, sex and education). b. PIB+ participants perform worse than PIB− participants (P = 0.095); however after correcting for age, sex and education PIB groups did not differ in executive functioning performance (P = .47). c. & d. Episodic memory performance did not differ based on CVD status (P = .92, corrected for age, sex and education) or PIB status (P = .57, corrected for age, sex and education). * P = 0.001.

PIB status was not a significant predictor of EXECUTIVE (F(1,48) = 0.52, P = 0.47; Fig. 4b). A linear regression, regressing EXECUTIVE against Global PIB Index, demonstrated no relationship between these variables (ΔR2 = 0.0, t = 0.0, P = 1.0).

Examining the effect of CVD and PIB status in the same model using an ANCOVA (with age, gender, and education as covariates), CVD status continued to be a significant predictor of EXECUTIVE (F(1,46) = 14.28, P < 0.001) while PIB was not. There was no interaction between CVD and PIB (F(1,46) = 1.78, P = 0.19); however power of the model to detect interactions was low and participants with CVD who were also PIB positive showed the worst performance: CVD−/PIB− (mean = 0.02, SE = 0.17), CVD−/PIB+ (mean = 0.2, SE = 0.24), CVD+/PIB− (mean = −0.5, SE = 0.17), CVD+/PIB+ (mean = −0.84, SE = 0.2).

Episodic Memory

CVD positive participants did not differ from CVD negative participants in MEMORY (F(1,40) = 0.01, P = 0.92; Fig. 4c). Presence of infarct did not affect MEMORY (F(1,40) = 0.13, P = 0.72), and percentage WMH was not correlated with MEMORY (ΔR2 = 0.02, t = 0.86, P = 0.39). In addition, PIB status did not explain MEMORY (F(1,40) = 0.33, P = 0.57; Fig. 4d). Moreover, no significant association was found between Global PIB Index and MEMORY performance using linear regression analysis ((ΔR2 = 0.01, t = 0.77, P = 0.45). An independent measures ANCOVA examining the effect of CVD and PIB together revealed no main effect of CVD status (F(1,38) = 0.03, P = 0.87) or PIB status (F(1,38) = 0.24, P = 0.63) and no interaction (F(1,38) = 0.92, P = 0.34).

To examine whether selection bias existed by different cohort norm groups for the measure of episodic memory, MEMORY from the BAC and Aging Brain cohorts were compared, as stratified by CVD and PIB status (BAC:CVD− vs Aging Brain:CVD−; BAC: CVD+ vs Aging Brain:CVD+; BAC:PIB− vs Aging Brain:PIB−; BAC:PIB+ vs Aging Brain:PIB+). Although group sizes were small, memory performance did not differ based on cohort even at the trend level (P’s > 0.47).

Conclusions

The primary aim of this study was to examine the relationship between CVD and Aβ aggregation, and their independent and interactive effects on cognition in non-demented older adults. We found that MRI measures of CVD and PIB-PET measures of Aβ were not related. In addition, our MRI measures of CVD were associated with poorer cognitive performance, particularly on tests reflecting frontal/executive function, while our PIB-PET Aβ measures did not influence cognition. There was no statistical interaction between these pathologies on cognition, possibly due to the limited power (EXECUTIVE = .43, MEMORY = .37) to detect a medium sized (.25) interaction (Faul et al., 2007). However, individuals with both CVD and significant Aβ burden did show the most impaired executive function suggesting the possibility that these two processes may have an additive negative effect on cognition as previously indicated by pathological studies (Schneider et al., 2004). This additive effect was not seen in memory performance. It is worth noting, that the combined cognitive effects of these pathologies are most frequently studied in groups of cognitively impaired or demented individuals (Schneider et al., 2009).

In the present study CVD emerged as the only contributor to cognitive dysfunction. Specifically, individuals with MRI-identified markers of CVD showed worse executive functioning than those with no evidence of CVD. When examining the components of CVD individually, this effect was primarily driven by subcortical infarction, although there was also a trend for WMH volume to be negatively associated with executive functioning. CVD status did not affect episodic memory. These findings are in agreement with previous research demonstrating that subcortical vascular disease – in non-demented adults – is associated with impairment in frontal lobe-dependent tasks (Benisty et al., 2009; Brickman et al., 2009; Bunce et al., 2010; DeCarli et al., 1995; He et al., 2010; Prins et al., 2005; Tullberg et al., 2004), particularly tasks of cognitive control (Mayda et al., 2011; Nordahl et al., 2006) and is likely caused by damage to frontal-subcortical circuitry (Chui, 2007; Cummings, 1993). By excluding AD pathology as a mediator of the association between CVD and executive dysfunction, the present study extends that literature and underscores the adverse impact of CVD in clinically normal older adults.

Amyloid burden, as measured by PIB-PET imaging, did not explain performance in either executive functioning or episodic memory. Moreover, no linear relationship existed between Aβ and cognition when PIB uptake was treated as a continuous measure. There was a trend for individuals with significant amyloid burden to show worse executive functioning, however this effect was driven by the lower education of the PIB positive group. These findings support those of Aizenstein and colleagues (2008) who found no direct effect of amyloid burden on cognition in non-demented individuals. The amyloid cascade hypothesis proposes that Aβ is an initiating factor in the progression towards AD (Hardy and Selkoe, 2002); therefore, in cognitively intact older adults it may be the delayed sequelae of Aβ deposition, such as regional atrophy or tau aggregation, that produce cognitive deficits (Jack et al., 2009; Mormino et al., 2009; Oh et al., 2011). Indeed, pathological data indicate a relationship between Aβ plaques and memory primarily when cognitively impaired and AD participants are included in the analyses (Chui et al., 2006; Reed et al., 2007).

CVD specifically injures neurons and the connections between them, while Aβ aggregation per se, does not necessarily do either. Pathology studies show that cognitive function more strongly correlates with neuronal loss and neurofibrillary tangles than with Aβ plaques (Giannakopoulos et al., 2007; Nelson et al., 2010), indicating it is not the presence of plaques but rather the loss of neurons and synapses that impairs cognition. We found little statistical evidence that concomitant Aβ deposition alters the impact of CVD on cognition in this sample of non-demented older adults; however individuals with both CVD and significant amyloid burden did perform worse than other groups suggesting a possible additive effect. CVD may cause a decline in cognitive performance following vascular insults, while amyloid aggregation may signify onset of progressive neurodegeneration, namely AD, and contribute more substantively to the effects of the vascular injury later in the AD process. Indeed our PIB PET measures of Aβ in the high PIB sample of cognitively normal adults were below those seen in amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment (eg. Jack et al., 2008).

This study provides further demonstration that CVD and Aβ deposition occur in non-demented individuals (Tomlinson et al., 1968). Additionally, presence of CVD and Aβ deposition appear to be independent. While Reed et al. (this issue) found a relationship between Aβ deposition and vascular risk (measured using the Framingham Cardiovascular Risk Profile; Wilson et al., 1998), these results are not necessarily contradictory. We found no relationship between our measure of vascular risk and Aβ, which supports the findings of Reed et al. who saw no effect of the individual components of the FCRP on Aβ, only the empirically developed weighted sum. Additionally, increased vascular risk may predispose to CVD or Aβ aggregation, however this does not necessitate a direct association between CVD and Aβ. For example, Jagust et al. (2008) found that MR cortical atrophy was independently related to postmortem measurements of both CVD and Alzheimer pathology.

Given recent studies suggesting a relationship between Aβ and white matter damage (Horiuchi et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2009), the relationship between Aβ with WMH volume and subcortical infarct was individually assessed to examine whether a specific form of vascular damage might be related to Aβ aggregation, and we found no relationship with either form of CVD. This was true when Aβ was treated as a categorical or a continuous variable. It is interesting to note that the three participants with cortical infarct showed significant amyloid burden. While the numbers at this stage are too small to draw strong conclusions, it is possible that different types and stages of vascular damage may be differentially related to amyloid burden.

This lack of association between CVD and PIB in clinically normal individuals leaves open several possibilities. First, Aβ aggregation may be independent of vascular integrity and the presence of CVD may simply lower the threshold for symptomology of AD (Esiri et al., 1999; Snowdon et al., 1997). The recognition of more frequent mixed CVD/AD dementia could be due to improvements in identification of these diseases. Second and not unrelated, we may not see a relationship between these pathologies due to the sample – individuals with both CVD and significant amyloid burden may be less likely to remain cognitively intact. In support of this theory, individuals in the present study with both significant CVD and Aβ pathology showed a trend for worse cognition. Examining CVD and amyloid aggregation in individuals diagnosed with MCI or mild AD would help clarify this point.

Finally, the type and location of lesion may be important in determining whether a relationship exists between vascular health and amyloid, rather than simply the presence or absence of lesion (or overall volume of WMH). For example, the regional distribution of WMH and subcortical infarcts may be an important determinant in Aβ aggregation, as these considerations have also been shown to affect cognition (Benisty et al., 2009; Cummings, 1993; Mungas et al., 2001). Additionally, measuring amyloid levels in a greater number of individuals with cortical infarct would help explain whether cortical lesions interact with amyloid levels.

There are several strengths of this study. It is the first study to date that directly examines CVD and Aβ deposition in vivo in a large number of non-demented individuals. Even though CVD is a frequent age-related change, patients with this pathology may be excluded from studies of AD and amyloid pathology because of its potential to confound results. White matter lesions were quantified using a semi-automated procedure with the advantage of overcoming the finite range of values generally encountered with qualitative methods (Yoshita et al., 2005). This was especially important given the vascular-enriched cohort that was studied. Infarct (cortical vs subcortical) and white matter lesions were examined separately to broadly explore whether type and location of lesion might affect the findings. Finally, only cognitively intact individuals were included in the present study to target the influence of CVD and Aβ early in their course of development to minimize the influence of downstream effects of these pathologies.

The present study also has limitations. The use of a different normative group for each cohort to generate the Z transform measure of episodic memory may have confounded the results. By showing that there was no effect of normative group on memory score, we validated that the lack of difference in memory performance based on either CVD or PIB status is unlikely due to the difference in normative groups. The possibility remains that a regional association of PIB uptake with cognition may exist, and has been suggested by others (Chetelat et al., 2011). Additionally, a more comprehensive differentiation of lesion type and location would have allowed us to explore specific relationships between lesion, PIB and cognition; however this was not possible due to the sample size. Finally, the cross-sectional design of the present study only allows us to state that at this time point CVD and Aβ appear to be independent. Longitudinal follow-up would allow us to examine whether significant Aβ deposition will occur more rapidly and/or lead to earlier cognitive decline or dementia in these individuals with CVD.

In conclusion, our results suggest ischemic cerebrovascular disease may not be amyloidogenic in cognitively normal older adults, and that within this group cognition is more influenced by CVD than Aβ. CVD was specifically associated with worse executive functioning, and amyloid deposition showed no effect on cognition. Clearly, the role of Aβ and its downstream pathology become highly detrimental to cognition as the full pathogenic process of AD unfolds. Relationships between these two complex disorders are, very likely, themselves complex and dependent on the stage and aspect of the disease under consideration.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grants AG012435 and AG034570 and by the Alzheimer’s Association (ZEN-08-87090). We thank Adi Alkalay, Nexi Delgado, Amynta Hayenga, Stephen Krieger, Joel Laxamana, Candace Markley, Shawn Marks, Oliver Martinez, and Elizabeth Mormino for assistance with participant recruitment, cognitive testing, and image analysis.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

| I) Scientific Advisory Boards 2009: a. Elan/Wyeth Alzheimer’s Immunotherapy Program North American Advisory Board b. Novartis Misfolded Protein Scientific Advisory Board Meeting c. Banner Alzheimer’s Institute Alzheimer’s Prevention Initiative Advisory Board Meeting d. Research Advisory Committee on Gulf War Veterans’ Illnesses 2010: e. Lilly f. Araclon and Institut Catala de Neurociencies Aplicades g. Gulf War Veterans Illnesses Advisory Committee, VACO h. Biogen Idec 2011 i. Pfizer a. Elan/Wyeth Alzheimer’s Immunotherapy Program North American Advisory Board b. Alzheimer’s Association c. Forest d. University of California, Davis e. Tel-Aviv University Medical School f. Colloquium Paris g. Ipsen h. Wenner-Gren Foundations i. Social Security Administration j. Korean Neurological Association k. National Institutes of Health l. Washington University at St. Louis m. Banner Alzheimer’s Institute n. Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease o. Veterans Affairs Central Office p. Beijing Institute of Geriatrics q. Innogenetics r. New York University 2010: a. NeuroVigil, Inc. b. CHRU-Hopital Roger Salengro c. Siemens d. AstraZeneca e. Geneva University Hospitals f. Lilly g. University of California, San Diego - ADNI h. Paris University i. Institut Catala de Neurociencies Aplicades j. University of New Mexico School of Medicine k. Ipsen l. CTAD (Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease) 2011 a. Pfizer b. AD PD meeting c. Paul Sabatier University AstraZeneca Bayer Healthcare BioClinica, Inc. (ADNI 2) Bristol-Myers Squibb Cure Alzheimer’s Fund Eisai Elan Gene Network Sciences Genentech GE Healthcare GlaxoSmithKline Innogenetics Johnson & Johnson Eli Lilly & Company Medpace Merck Novartis Pfizer Inc Roche Schering Plough Synarc Wyeth |

II) Consulting 2009: a. Elan/Wyeth b. Novartis c. Forest d. Ipsen e. Daiichi Sankyo, Inc. 2010: f. Astra Zeneca g. Araclon h. Medivation/Pfizer i. Ipsen j. TauRx Therapeutics LTD k. Bayer Healthcare l. Biogen Idec m. Exonhit Therapeutics, SA n. Servier o. Synarc 2011 p. Pfizer III) Funding for Travel 2009: d. Novartis IV) Editorial Advisory Board a. Alzheimer’s & Dementia b. MRI V) Honoraria 2009: a. American Academy of Neurology b. Ipsen 2010: c. NeuroVigil, Inc. d. Insitut Catala de Neurociencies Aplicades VI) Commercial Entities Research Support a. Merck b. Avid VII) Government Entities Research Support a. NIH b. DOD c. VA VIII) Stock options a. Synarc b. Elan IX) Organizations contributing to the Foundation for NIH and thus to the NIA funded Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Abbott Alzheimer’s Association Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation Anonymous Foundation |

References

- Aizenstein HJ, Nebes RD, Saxton JA, Price JC, Mathis CA, Tsopelas ND, Ziolko SK, James JA, Snitz BE, Houck PR, Bi W, Cohen AD, Lopresti BJ, DeKosky ST, Halligan EM, Klunk WE. Frequent amyloid deposition without significant cognitive impairment among the elderly. Arch Neurol. 2008;65(11):1509–17. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.11.1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benisty S, Gouw AA, Porcher R, Madureira S, Hernandez K, Poggesi A, van der Flier WM, Van Straaten EC, Verdelho A, Ferro J, Pantoni L, Inzitari D, Barkhof F, Fazekas F, Chabriat H. Location of lacunar infarcts correlates with cognition in a sample of non-disabled subjects with age-related white-matter changes: the LADIS study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80(5):478–83. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2008.160440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, Kelly JF, Aggarwal NT, Shah RC, Wilson RS. Neuropathology of older persons without cognitive impairment from two community-based studies. Neurology. 2006;66(12):1837–44. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000219668.47116.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernick C, Kuller L, Dulberg C, Longstreth WT, Jr., Manolio T, Beauchamp N, Price T. Silent MRI infarcts and the risk of future stroke: the cardiovascular health study. Neurology. 2001;57(7):1222–9. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.7.1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breteler MM. Vascular risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease: an epidemiologic perspective. Neurobiol Aging. 2000;21(2):153–60. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(99)00110-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brickman AM, Siedlecki KL, Muraskin J, Manly JJ, Luchsinger JA, Yeung LK, Brown TR, Decarli C, Stern Y. White matter hyperintensities and cognition: Testing the reserve hypothesis. Neurobiol Aging. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunce D, Anstey KJ, Cherbuin N, Burns R, Christensen H, Wen W, Sachdev PS. Cognitive deficits are associated with frontal and temporal lobe white matter lesions in middle-aged adults living in the community. PLoS One. 2010;5(10):e13567. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey CL, Kramer JH, Josephson SA, Mungas D, Reed BR, Schuff N, Weiner MW, Chui HC. Subcortical lacunes are associated with executive dysfunction in cognitively normal elderly. Stroke. 2008;39(2):397–402. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.491795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chetelat G, Villemagne VL, Pike KE, Ellis KA, Bourgeat P, Jones G, O’Keefe GJ, Salvado O, Szoeke C, Martins RN, Ames D, Masters CL, Rowe CC. Independent contribution of temporal beta-amyloid deposition to memory decline in the pre-dementia phase of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2011;134(Pt 3):798–807. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chui HC. Subcortical ischemic vascular dementia. Neurol Clin. 2007;25(3):717–40. vi. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chui HC, Zarow C, Mack WJ, Ellis WG, Zheng L, Jagust WJ, Mungas D, Reed BR, Kramer JH, Decarli CC, Weiner MW, Vinters HV. Cognitive impact of subcortical vascular and Alzheimer’s disease pathology. Ann Neurol. 2006;60(6):677–87. doi: 10.1002/ana.21009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crystal HA, Dickson DW, Sliwinski MJ, Lipton RB, Grober E, Marks-Nelson H, Antis P. Pathological markers associated with normal aging and dementia in the elderly. Ann Neurol. 1993;34(4):566–73. doi: 10.1002/ana.410340410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings JL. Frontal-subcortical circuits and human behavior. Arch Neurol. 1993;50(8):873–80. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1993.00540080076020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debette S, Beiser A, DeCarli C, Au R, Himali JJ, Kelly-Hayes M, Romero JR, Kase CS, Wolf PA, Seshadri S. Association of MRI markers of vascular brain injury with incident stroke, mild cognitive impairment, dementia, and mortality: the Framingham Offspring Study. Stroke. 2010;41(4):600–6. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.570044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeCarli C, Maisog J, Murphy DG, Teichberg D, Rapoport SI, Horwitz B. Method for quantification of brain, ventricular, and subarachnoid CSF volumes from MR images. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1992;16(2):274–84. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199203000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decarli C, Massaro J, Harvey D, Hald J, Tullberg M, Au R, Beiser A, D’Agostino R, Wolf PA. Measures of brain morphology and infarction in the framingham heart study: establishing what is normal. Neurobiol Aging. 2005;26(4):491–510. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeCarli C, Murphy DG, Teichberg D, Campbell G, Sobering GS. Local histogram correction of MRI spatially dependent image pixel intensity nonuniformity. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1996;6(3):519–28. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880060316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeCarli C, Murphy DG, Tranh M, Grady CL, Haxby JV, Gillette JA, Salerno JA, Gonzales-Aviles A, Horwitz B, Rapoport SI, et al. The effect of white matter hyperintensity volume on brain structure, cognitive performance, and cerebral metabolism of glucose in 51 healthy adults. Neurology. 1995;45(11):2077–84. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.11.2077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delis DC, Kramer JH, Kaplan E, Ober BA. The California Verbal Learning Test. Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Esiri MM, Nagy Z, Smith MZ, Barnetson L, Smith AD. Cerebrovascular disease and threshold for dementia in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet. 1999;354(9182):919–20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)02355-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esiri MM, Wilcock GK. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy in dementia and old age. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1986;49(11):1221–6. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.49.11.1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39(2):175–91. doi: 10.3758/bf03193146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannakopoulos P, Gold G, Kovari E, von Gunten A, Imhof A, Bouras C, Hof PR. Assessing the cognitive impact of Alzheimer disease pathology and vascular burden in the aging brain: the Geneva experience. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;113(1):1–12. doi: 10.1007/s00401-006-0144-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold G, Giannakopoulos P, Herrmann FR, Bouras C, Kovari E. Identification of Alzheimer and vascular lesion thresholds for mixed dementia. Brain. 2007;130(Pt 11):2830–6. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hachinski V, Munoz DG. Cerebrovascular pathology in Alzheimer’s disease: cause, effect or epiphenomenon? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1997;826:1–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb48456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han BH, Zhou ML, Abousaleh F, Brendza RP, Dietrich HH, Koenigsknecht-Talboo J, Cirrito JR, Milner E, Holtzman DM, Zipfel GJ. Cerebrovascular dysfunction in amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice: contribution of soluble and insoluble amyloid-beta peptide, partial restoration via gamma-secretase inhibition. J Neurosci. 2008;28(50):13542–50. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4686-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 2002;297(5580):353–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J, Iosif AM, Lee DY, Martinez O, Chu S, Carmichael O, Mortimer JA, Zhao Q, Ding D, Guo Q, Galasko D, Salmon DP, Dai Q, Wu Y, Petersen RC, Hong Z, Borenstein AR, DeCarli C. Brain structure and cerebrovascular risk in cognitively impaired patients: Shanghai Community Brain Health Initiative-pilot phase. Arch Neurol. 2010;67(10):1231–7. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henon H, Durieu I, Guerouaou D, Lebert F, Pasquier F, Leys D. Poststroke dementia: incidence and relationship to prestroke cognitive decline. Neurology. 2001;57(7):1216–22. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.7.1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horiuchi M, Maezawa I, Itoh A, Wakayama K, Jin LW, Itoh T, Decarli C. Amyloid beta1-42 oligomer inhibits myelin sheet formation in vitro. Neurobiol Aging. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack CR, Jr., Lowe VJ, Senjem ML, Weigand SD, Kemp BJ, Shiung MM, Knopman DS, Boeve BF, Klunk WE, Mathis CA, Petersen RC. C PiB and structural MRI provide complementary information in imaging of Alzheimer’s disease and amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Brain. 2008;131(Pt 3):665–80. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack CR, Jr., Lowe VJ, Weigand SD, Wiste HJ, Senjem ML, Knopman DS, Shiung MM, Gunter JL, Boeve BF, Kemp BJ, Weiner M, Petersen RC. Serial PIB and MRI in normal, mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease: implications for sequence of pathological events in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2009;132(Pt 5):1355–65. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagust WJ, Zheng L, Harvey DJ, Mack WJ, Vinters HV, Weiner MW, Ellis WG, Zarow C, Mungas D, Reed BR, Kramer JH, Schuff N, DeCarli C, Chui HC. Neuropathological basis of magnetic resonance images in aging and dementia. Ann Neurol. 2008;63(1):72–80. doi: 10.1002/ana.21296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeerakathil T, Wolf PA, Beiser A, Massaro J, Seshadri S, D’Agostino RB, DeCarli C. Stroke risk profile predicts white matter hyperintensity volume: the Framingham Study. Stroke. 2004;35(8):1857–61. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000135226.53499.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klunk WE, Engler H, Nordberg A, Wang Y, Blomqvist G, Holt DP, Bergstrom M, Savitcheva I, Huang GF, Estrada S, Ausen B, Debnath ML, Barletta J, Price JC, Sandell J, Lopresti BJ, Wall A, Koivisto P, Antoni G, Mathis CA, Langstrom B. Imaging brain amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease with Pittsburgh Compound-B. Ann Neurol. 2004;55(3):306–19. doi: 10.1002/ana.20009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knopman DS, Parisi JE, Salviati A, Floriach-Robert M, Boeve BF, Ivnik RJ, Smith GE, Dickson DW, Johnson KA, Petersen LE, McDonald WC, Braak H, Petersen RC. Neuropathology of cognitively normal elderly. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2003;62(11):1087–95. doi: 10.1093/jnen/62.11.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DY, Fletcher E, Martinez O, Ortega M, Zozulya N, Kim J, Tran J, Buonocore M, Carmichael O, Decarli C. Regional pattern of white matter microstructural changes in normal aging, MCI, and AD. Neurology. 2009;73(21):1722–8. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c33afb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Kim SH, Kim GH, Seo SW, Park HK, Oh SJ, Kim JS, Cheong HK, Na DL. Identification of pure subcortical vascular dementia using 11C-Pittsburgh compound B. Neurology. 2011 doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318221acee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan J, Fowler JS, Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Ding YS, Alexoff DL. Distribution volume ratios without blood sampling from graphical analysis of PET data. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1996;16(5):834–40. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199609000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathis CA, Wang Y, Holt DP, Huang GF, Debnath ML, Klunk WE. Synthesis and evaluation of 11C-labeled 6-substituted 2-arylbenzothiazoles as amyloid imaging agents. J Med Chem. 2003;46(13):2740–54. doi: 10.1021/jm030026b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayda AB, Westphal A, Carter CS, Decarli C. Late life cognitive control deficits are accentuated by white matter disease burden. Brain. 2011 doi: 10.1093/brain/awr065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mielke MM, Rosenberg PB, Tschanz J, Cook L, Corcoran C, Hayden KM, Norton M, Rabins PV, Green RC, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Breitner JC, Munger R, Lyketsos CG. Vascular factors predict rate of progression in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2007;69(19):1850–8. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000279520.59792.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mintun MA, Larossa GN, Sheline YI, Dence CS, Lee SY, Mach RH, Klunk WE, Mathis CA, DeKosky ST, Morris JC. [11C]PIB in a nondemented population: potential antecedent marker of Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2006;67(3):446–52. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000228230.26044.a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mormino EC, Kluth JT, Madison CM, Rabinovici GD, Baker SL, Miller BL, Koeppe RA, Mathis CA, Weiner MW, Jagust WJ. Episodic memory loss is related to hippocampal-mediated beta-amyloid deposition in elderly subjects. Brain. 2009;132(Pt 5):1310–23. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JC, Roe CM, Grant EA, Head D, Storandt M, Goate AM, Fagan AM, Holtzman DM, Mintun MA. Pittsburgh compound B imaging and prediction of progression from cognitive normality to symptomatic Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2009;66(12):1469–75. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mungas D, Jagust WJ, Reed BR, Kramer JH, Weiner MW, Schuff N, Norman D, Mack WJ, Willis L, Chui HC. MRI predictors of cognition in subcortical ischemic vascular disease and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 2001;57(12):2229–35. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.12.2229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson PT, Kukull WA, Frosch MP. Thinking outside the box: Alzheimer-type neuropathology that does not map directly onto current consensus recommendations. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2010;69(5):449–54. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181d8db07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuropathology Group Medical Research Council Cognitive Function and Ageing Study. Pathological correlates of late-onset dementia in a multicentre, community-based population in England and Wales. Lancet. 2001;357(9251):169–75. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)03589-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman AB, Fitzpatrick AL, Lopez O, Jackson S, Lyketsos C, Jagust W, Ives D, Dekosky ST, Kuller LH. Dementia and Alzheimer’s disease incidence in relationship to cardiovascular disease in the Cardiovascular Health Study cohort. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(7):1101–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordahl CW, Ranganath C, Yonelinas AP, Decarli C, Fletcher E, Jagust WJ. White matter changes compromise prefrontal cortex function in healthy elderly individuals. J Cogn Neurosci. 2006;18(3):418–29. doi: 10.1162/089892906775990552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh H, Mormino EC, Madison C, Hayenga A, Smiljic A, Jagust WJ. beta-Amyloid affects frontal and posterior brain networks in normal aging. Neuroimage. 2011;54(3):1887–95. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pendlebury ST, Rothwell PM. Prevalence, incidence, and factors associated with pre-stroke and post-stroke dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(11):1006–18. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70236-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pike KE, Savage G, Villemagne VL, Ng S, Moss SA, Maruff P, Mathis CA, Klunk WE, Masters CL, Rowe CC. Beta-amyloid imaging and memory in non-demented individuals: evidence for preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2007;130(Pt 11):2837–44. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price JC, Klunk WE, Lopresti BJ, Lu X, Hoge JA, Ziolko SK, Holt DP, Meltzer CC, DeKosky ST, Mathis CA. Kinetic modeling of amyloid binding in humans using PET imaging and Pittsburgh Compound-B. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2005;25(11):1528–47. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prins ND, van Dijk EJ, den Heijer T, Vermeer SE, Jolles J, Koudstaal PJ, Hofman A, Breteler MM. Cerebral small-vessel disease and decline in information processing speed, executive function and memory. Brain. 2005;128(Pt 9):2034–41. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinovici GD, Furst AJ, Alkalay A, Racine CA, O’Neil JP, Janabi M, Baker SL, Agarwal N, Bonasera SJ, Mormino EC, Weiner MW, Gorno-Tempini ML, Rosen HJ, Miller BL, Jagust WJ. Increased metabolic vulnerability in early-onset Alzheimer’s disease is not related to amyloid burden. Brain. 2010;133(Pt 2):512–28. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed B, Marchant N, Jagust WJ, DeCarli C, Chui HC. Coronary risk correlates with cerebral amyloid deposition. Neurobiol Aging. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed BR, Eberling JL, Mungas D, Weiner M, Kramer JH, Jagust WJ. Effects of white matter lesions and lacunes on cortical function. Arch Neurol. 2004;61(10):1545–50. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.10.1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed BR, Mungas DM, Kramer JH, Ellis W, Vinters HV, Zarow C, Jagust WJ, Chui HC. Profiles of neuropsychological impairment in autopsy-defined Alzheimer’s disease and cerebrovascular disease. Brain. 2007;130(Pt 3):731–9. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick SM, Sojkova J, Zhou Y, An Y, Ye W, Holt DP, Dannals RF, Mathis CA, Klunk WE, Ferrucci L, Kraut MA, Wong DF. Longitudinal cognitive decline is associated with fibrillar amyloid-beta measured by [11C]PiB. Neurology. 2010;74(10):807–15. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181d3e3e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riekse RG, Leverenz JB, McCormick W, Bowen JD, Teri L, Nochlin D, Simpson K, Eugenio C, Larson EB, Tsuang D. Effect of vascular lesions on cognition in Alzheimer’s disease: a community-based study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(9):1442–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52405.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe CC, Ng S, Ackermann U, Gong SJ, Pike K, Savage G, Cowie TF, Dickinson KL, Maruff P, Darby D, Smith C, Woodward M, Merory J, Tochon-Danguy H, O’Keefe G, Klunk WE, Mathis CA, Price JC, Masters CL, Villemagne VL. Imaging beta-amyloid burden in aging and dementia. Neurology. 2007;68(20):1718–25. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000261919.22630.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, Bang W, Bennett DA. Mixed brain pathologies account for most dementia cases in community-dwelling older persons. Neurology. 2007;69(24):2197–204. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000271090.28148.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, Leurgans SE, Bennett DA. The neuropathology of probable Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment. Ann Neurol. 2009;66(2):200–8. doi: 10.1002/ana.21706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider JA, Wilson RS, Bienias JL, Evans DA, Bennett DA. Cerebral infarctions and the likelihood of dementia from Alzheimer disease pathology. Neurology. 2004;62(7):1148–55. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000118211.78503.f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skoog I, Kalaria RN, Breteler MM. Vascular factors and Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1999;13(Suppl 3):S106–14. doi: 10.1097/00002093-199912003-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snowdon DA, Greiner LH, Mortimer JA, Riley KP, Greiner PA, Markesbery WR. Brain infarction and the clinical expression of Alzheimer disease. The Nun Study. JAMA. 1997;277(10):813–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun FT, Schriber RA, Greenia JM, He J, Gitcho A, Jagust WJ. Automated template-based PET region of interest analyses in the aging brain. Neuroimage. 2007;34(2):608–17. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson BE, Blessed G, Roth M. Observations on the brains of non-demented old people. J Neurol Sci. 1968;7(2):331–56. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(68)90154-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tullberg M, Fletcher E, DeCarli C, Mungas D, Reed BR, Harvey DJ, Weiner MW, Chui HC, Jagust WJ. White matter lesions impair frontal lobe function regardless of their location. Neurology. 2004;63(2):246–53. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000130530.55104.b5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzourio-Mazoyer N, Landeau B, Papathanassiou D, Crivello F, Etard O, Delcroix N, Mazoyer B, Joliot M. Automated anatomical labeling of activations in SPM using a macroscopic anatomical parcellation of the MNI MRI single-subject brain. Neuroimage. 2002;15(1):273–89. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Flier WM, van Straaten EC, Barkhof F, Verdelho A, Madureira S, Pantoni L, Inzitari D, Erkinjuntti T, Crisby M, Waldemar G, Schmidt R, Fazekas F, Scheltens P. Small vessel disease and general cognitive function in nondisabled elderly: the LADIS study. Stroke. 2005;36(10):2116–20. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000179092.59909.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villemagne VL, Pike KE, Chetelat G, Ellis KA, Mulligan RS, Bourgeat P, Ackermann U, Jones G, Szoeke C, Salvado O, Martins R, O’Keefe G, Mathis CA, Klunk WE, Ames D, Masters CL, Rowe CC. Longitudinal assessment of Abeta and cognition in aging and Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol. 2011;69(1):181–92. doi: 10.1002/ana.22248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahlund L-O, Erkinjuntti T, Gauthier S. Vascular Cognitive Impairment in Clinical Practice. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Williams JM. Memory Assessment Scales. Psychological Assessment Resources. Odessa, FL: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson PW, D’Agostino RB, Levy D, Belanger AM, Silbershatz H, Kannel WB. Prediction of coronary heart disease using risk factor categories. Circulation. 1998;97(18):1837–47. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.18.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshita M, Fletcher E, DeCarli C. Current concepts of analysis of cerebral white matter hyperintensities on magnetic resonance imaging. Top Magn Reson Imaging. 2005;16(6):399–407. doi: 10.1097/01.rmr.0000245456.98029.a8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Zhou K, Wang R, Cui J, Lipton SA, Liao FF, Xu H, Zhang YW. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha (HIF-1alpha)-mediated hypoxia increases BACE1 expression and beta-amyloid generation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(15):10873–80. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608856200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]