Abstract

Objectives

To investigate glucose regulation in young adults with very low birth weight (VLBW; <1500 g) in an Asian population.

Design

Cross-sectional observational study.

Setting

A general hospital in Hamamatsu, Japan.

Participants

111 young adults (42 men and 69 women; aged 19–30 years) born with VLBW between 1980 and 1990. Participants underwent standard 75 g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT).

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The primary outcomes were glucose and insulin levels during OGTT and risk factors for a category of hyperglycaemia defined as follows: diabetes mellitus, impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), impaired fasting glycaemia (IFG) and non-diabetes/IGT/IFG with elevated 1 h glucose levels (>8.6 mmol/l). The secondary outcomes were the pancreatic β cell function (insulinogenic index and homeostasis model of assessment for beta cell (HOMA-β)) and insulin resistance (homeostasis model of assessment for insulin resistance (HOMA-IR)).

Results

Of 111 young adults with VLBW, 21 subjects (19%) had hyperglycaemia: one had type 2 diabetes, six had IGT, one had IFG and 13 had non-diabetes/IGT/IFG with elevated 1 h glucose levels. In logistic regression analysis, male gender was an independent risk factor associated with hyperglycaemia (OR 3.34, 95% CI 1.08 to 10.3, p=0.036). Male subjects had significantly higher levels of glucose and lower levels of insulin during OGTT than female subjects (p<0.001 for glucose and p=0.005 for insulin by repeated measures analysis of variance). Pancreatic β cell function was lower in men (insulinogenic index: p=0.002; HOMA-β: p=0.001), although no gender difference was found in insulin resistance (HOMA-IR: p=0.477). In male subjects, logistic regression analysis showed that small for gestational age was an independent risk factor associated with hyperglycaemia (OR 33.3, 95% CI 1.67 to 662.6, p=0.022).

Conclusions

19% of individuals with VLBW already had hyperglycaemia in young adulthood, and male gender was a significant independent risk factor of hyperglycaemia. In male young adults with VLBW, small for gestational age was associated with hyperglycaemia.

Article summary

Article focus

Neonatal intensive care has improved the survival rate for very low birth weight infants (VLBW; birth weight <1500 g) in recent decades, and the first generation of VLBW infants have only recently reached young adulthood.

Only a few studies have shown that VLBW (or preterm) is associated with glucose intolerance in Caucasian young adults, while glucose regulation in Asian young adults with VLBW is still uncertain.

The present study investigated glucose regulation in young adults with VLBW in an Asian population and determined the factors associated with hyperglycaemia.

Key messages

Of 111 young adults with VLBW, 19% of individuals already had hyperglycaemia (type 2 diabetes, impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), impaired fasting glycaemia (IFG) and non-diabetes/IGT/IFG with elevated 1 h glucose levels).

Male gender was a significant independent risk factor of hyperglycaemia in young adults with VLBW.

Small for gestational age was associated with hyperglycaemia particularly in male young adults with VLBW.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This is the first study assessing the glucose regulation in young adults with VLBW in an Asian population.

This study does not provide information on postnatal growth patterns, which have been shown to be associated with later hyperglycaemia in previous studies.

The study design with no control subjects makes it impossible to address the delayed impact of VLBW itself on glucose regulation.

Introduction

In recent decades, progression of neonatal intensive care has dramatically increased the survival rate of very low birth weight (VLBW; birth weight <1500 g) infants worldwide.1 A lot of them have grown up into young adults (now in their 20s or 30s). To date, epidemiological studies have shown an association between low birth weight and type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease in later life.2–4 Fetal malnutrition in the gestational period, which prevents appropriate fetal growth in utero, is thought to provoke thrifty phenotype in premature babies. This phenotype is assumed to predispose them to subsequent metabolic disorders. For this reason, to foresee the later risk of type 2 diabetes is very crucial for VLBW infants, which would lead to prevention of type 2 diabetes by early intervention in their lifestyle.5–7

The first generation of VLBW infants have only recently reached young adulthood. A few studies have shown that VLBW (or preterm) is associated with glucose intolerance in young adulthood in Caucasian populations,8 9 while the glucose regulation in Asian young adults with VLBW remains uncertain. To clarify the characteristics of glucose metabolism in young adults with VLBW in an Asian population, we investigated glucose regulation in 111 young adults with VLBW by performing detailed oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), which is useful for evaluation of early signs of glucose intolerance.

Methods

Study participants

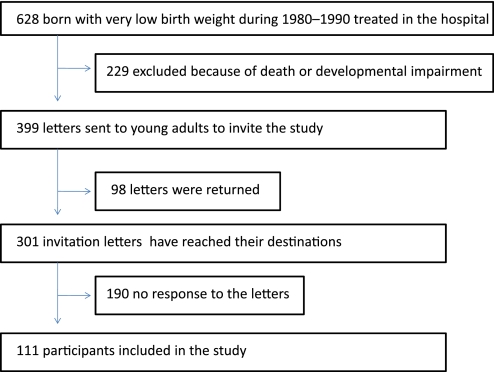

The birth record database of Seirei Hamamatsu General Hospital (Hamamatsu, Japan) showed that 628 subjects were born with VLBW between 1980 and 1990 and were treated at a neonatal intensive care unit (figure 1). VLBW infants were defined according to WHO criteria: babies whose birth weight was <1500 g. Out of the 628 subjects, 229 were excluded because of death (n=132) or severe neurodevelopmental impairment (n=97). To the remaining 399 subjects, we sent letters that provided information regarding the study and requested their participation. Among the 399 letters, 98 were returned marked as address unknown (ie, the remaining 301 letters were thought to reach their destinations). Consequently, 111 subjects (aged 19–30 years) participated in the present study. All participants were Japanese. Small for gestational age (SGA) status was determined according to standards by a study group of the Health Ministry in Japan: a birth weight below the 10th percentile for gestational age.10 The basal characteristics of participants at birth are summarised in table 1.

Figure 1.

Flow of participants through the study.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of young adults with very low birth weight at birth and at study assessment

| Total (n=111) | Men (n=42) |

Women (n=69) |

|||

| SGA* (n=14) | AGA (n=28) | SGA* (n=25) | AGA (n=44) | ||

| At birth | |||||

| Gestational age (wk) | 29.7 (3.1) | 31.5 (3.7) | 28.1 (1.9) | 33.0 (2.6) | 28.2 (1.9) |

| Weight (g) | 1152 (235) | 1050 (223) | 1149 (235) | 1190 (239) | 1166 (236) |

| ELBW | 33 (29.7) | 6 (42.9) | 10 (35.7) | 7 (28.0) | 10 (22.7) |

| Birth from multiple pregnancy | 18 (16.2) | 2 (14.3) | 7 (25.0) | 1 (4.0) | 8 (18.2) |

| At study assessment | |||||

| Age (yr) | 24.8 (3.0) | 24.9 (2.9) | 24.6 (3.6) | 23.9 (2.9) | 25.4 (2.7) |

| Family history of diabetes | 22 (19.8) | 2 (14.3) | 5 (17.9) | 7 (28.0) | 8 (18.2) |

| Height (m) | 1.58 (0.07) | 1.60 (0.06) | 1.66 (0.06) | 1.54 (0.06) | 1.55 (0.05) |

| Body weight (kg) | 52.3 (10.1) | 53.1 (8.8) | 55.8 (8.9) | 47.5 (8.3) | 52.4 (11.3) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 20.9 (3.8) | 20.8 (3.2) | 20.3 (2.8) | 20.1 (3.0) | 21.7 (4.7) |

| Blood pressure (mm Hg) | |||||

| Systolic | 118 (16) | 120 (18) | 121 (17) | 115 (12) | 117 (16) |

| Diastolic | 70 (11) | 69 (15) | 69 (11) | 69 (11) | 71 (11) |

| Cholesterol (mg/dl) | |||||

| Total | 184.8 (31.3) | 210.6 (52.0) | 183.4 (25.2) | 180.4 (27.2) | 179.9 (25.1) |

| LDL | 104.3 (28.4) | 126.9 (48.6) | 104.8 (24.8) | 100.3 (21.5) | 99.0 (22.6) |

| HDL | 65.7 (13.3) | 63.2 (14.0) | 64.6 (14.1) | 64.6 (15.1) | 67.8 (11.6) |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 81.8 (72.2) | 126.5 (139.9) | 81.0 (84.5) | 85.4 (51.0) | 65.9 (23.5) |

| Renal function | |||||

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.66 (0.13) | 0.76 (0.09) | 0.80 (0.11) | 0.59 (0.08) | 0.58 (0.08) |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73 m2)† | 104.6 (18.4) | 105.5 (13.9) | 101.8 (19.4) | 104.3 (18.2) | 106.3 (19.5) |

Determined by a birth weight below the 10th percentile for gestational age according to standards defined by a study group of the Health Ministry in Japan.

Calculated according to the formula recommended by the Japanese Society of Nephrology: eGFR (ml/min/1.73 m2)=194 × [Cre (mg/dl)]−1.094 × [Age (years)]−0.287 (×0.739 if the subject is a woman).

AGA, appropriate for gestational age; BMI, body mass index; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; ELBW, extremely low birth weight (<1000 g); HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; SGA, small for gestational age.

Data are expressed as mean (SD) or number (%).

Measurements

All participants underwent a standard 75 g OGTT after a 10 h overnight fast. Plasma glucose and serum insulin concentrations were examined at 0, 30, 60, 90, 120 and 180 min during OGTT. Fasting glucose levels and 2 h glucose levels were used for diagnosing diabetes mellitus, impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) and impaired fasting glycaemia (IFG) according to WHO criteria.11 Since it has been shown that 1 h plasma glucose concentration is associated with future risk of type 2 diabetes and atherosclerosis, 1 h plasma glucose above 8.6 mmol/l (155 mg/dl) was included as a category of hyperglycaemia.12 13 Reactive hypoglycaemias during OGTT was defined as the level of plasma glucose <3.8 mmol/l, which causes the response of counter-regulatory hormone release.14

We measured plasma glucose and serum insulin levels during OGTT with an autoanalyzer JCA-BM2250 (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan). Plasma glucose was measured by means of hexokinase method. The concentration of serum insulin was measured with chemiluminescent enzyme immunoassay. Fasting blood samples were also drawn for other measurements, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglyceride and creatinine. Glycated haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) was measured with high-performance liquid chromatography method using an automated glycohaemoglobin analyser HLC-723G8 (Tosoh Bioscience, Tokyo, Japan). The values for HbA1c were converted from the Japanese Diabetes Society (JDS) values into the National Glycohaemoglobin Standardization Program (NGSP) equivalent values. The NGSP equivalent values were calculated with the formula: HbA1c (%) = JDS value (%)+0.4.15

Calculations and statistical analysis

Pancreatic β cell function was evaluated by both insulinogenic index and homeostasis model of assessment for beta cell (HOMA-β).16 Insulinogenic index, the index of early-phase insulin secretion, was calculated as the ratio of the increment in insulin concentration to the increment in glucose concentration ([30 min insulin (μU/ml) – fasting insulin]/[30 min glucose (mg/dl) − fasting glucose]). HOMA-β was calculated as follows: 20 × fasting insulin (μU/ml)/[fasting glucose (mmol/l) − 3.5]. Insulin resistance was estimated by homeostasis model of assessment for insulin resistance (HOMA-IR): fasting insulin (μU/ml) × fasting glucose (mmol/l)/22.5.16 The total amounts of glucose and insulin levels during OGTT were assessed by calculating areas under the curve (AUC) with trapezoid rules. The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated according to the following formula, as recommended by the Japanese Society of Nephrology: eGFR (ml/min/1.73 m2)=194 × [Cre (mg/dl)]−1.094 × [Age (years)]−0.287 (×0.739 if the subject is a woman).17

Quantitative variables were expressed as mean and SD or 95% CI; categorical variables were presented as number and percentage. Differences between groups were compared using the Student t test, the Mann–Whitney U test, the Pearson's χ2 test or the repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) as appropriate. The data on insulin levels during OGTT were logarithmically transformed before the repeated measures ANOVA. Logistic regression analysis, which included gender, family history of diabetes within the second degree, body mass index (BMI), gestational age, birth weight and SGA/AGA (appropriate for gestational age), was performed to estimate ORs for the category of hyperglycaemia. For the further investigation into glucose regulation, multiple linear regression analysis was conducted. Gender, family history of diabetes, BMI, gestational age, birth weight and SGA/AGA were included in the model. The data on HOMA-β, HOMA-IR, insulinogenic index and glucoseAUC were logarithmically transformed before analysis to meet the assumptions of normality. A p value of <0.05 was defined as statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using SAS software V.9.2 (SAS Institute) and the statistical software R V.2.12.2 (http://www.r-project.org).

Results

The basic characteristics of participants at study assessment are shown in table 1. Of 111 young adults with VLBW, 21 subjects (19%) had hyperglycaemia: one had type 2 diabetes, six had IGT, one had IFG and 13 non-diabetes/IGT/IFG subjects had elevated 1 h glucose levels (>8.6 mmol/l). Hyperglycaemia was more frequent in men than in women (26.2% for men vs 14.5% for women). In the logistic regression analysis adjusted for family history of diabetes within the second degree, BMI, gestational age, birth weight and SGA/AGA, male gender was a statistically significant independent factor associated with hyperglycaemia (OR 3.34, 95% CI 1.08 to 10.3, p=0.036). BMI at study assessment was also associated with hyperglycaemia (table 2).

Table 2.

Correlated factors for hyperglycaemia* in young adults with very low birth weight assessed by logistic regression analyses

| Variable | OR† (95% CI) | p Value |

| Gender (male) | 3.34 (1.08 to 10.3) | 0.036 |

| Factors at birth | ||

| Gestational age (wk) | 0.77 (0.53 to 1.12) | 0.165 |

| Weight (0.1 kg) | 1.39 (0.96 to 2.02) | 0.085 |

| SGA | 2.56 (0.37 to 17.5) | 0.340 |

| Factors at study assessment | ||

| Family history of diabetes | 1.92 (0.49 to 7.57) | 0.353 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 1.29 (1.11 to 1.49) | 0.001 |

A category of hyperglycaemia includes diabetes, impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), impaired fasting glycaemia (IFG) and non-diabetes/IGT/IFG with elevated 1 h glucose levels (>8.6 mmol/l).

Each OR is calculated from a model including gender, family history of diabetes, BMI, gestational age, birth weight and SGA/AGA (appropriate for gestational age).

BMI, body mass index; SGA, small for gestational age.

Gender difference

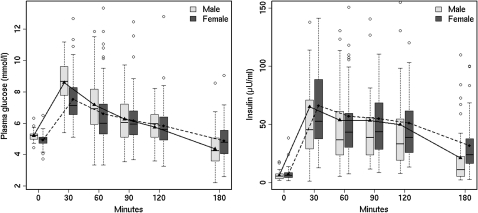

As male gender was a significant independent risk factor of hyperglycaemia, we evaluated the differences in glucose regulation between men and women in the sample group. Figure 2 shows the glucose and insulin response during OGTT in men and in women. Male subjects had significantly higher levels of glucose during OGTT than female subjects (p<0.001 by repeated measures ANOVA). In terms of insulin levels, male subjects had lower levels of insulin during OGTT than female subjects (p=0.005 by repeated measures ANOVA). GlucoseAUC during OGTT tended to be higher in male subjects (table 3). As for the function of insulin secretion, insulinogenic index and HOMA-β were significantly lower in men than in women. InsulinAUC also showed a tendency to be lower in male subjects. Reactive hypoglycaemias during OGTT tended to be frequent in men. The differences in the mean values of HbA1c and HOMA-IR were not statistically significant. There were no significant gender differences in gestational age (p=0.145), birth weight (p=0.168), age at study assessment (p=0.845), BMI (p=0.879), the proportion of SGA (p=0.756) and that of family history of diabetes within the second degree (p=0.516). The variables for glucose metabolism in men and women are summarised in table 3.

Figure 2.

The gender differences of glucose and insulin levels during oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) in young adults with very low birth weight. The top and bottom of the box indicate lower and upper quartiles; the line inside the box represents the median; the whiskers indicate the most extreme data points within 1.5 times of IQR from the box; dots indicate outliers. Male subjects had significantly higher levels of glucose and lower levels of insulin during OGTT than female subjects (p<0.001 for glucose and p=0.005 for insulin by repeated measures analysis of variance).

Table 3.

Gender differences in glucose regulation in young adults with very low birth weight

| Men (n=42) | Women (n=69) | p Value | |

| Hyperglycaemia | 11 (26.2) | 10 (14.5) | 0.127 |

| Diabetes | 0 | 1 | |

| IGT | 2 | 4 | |

| IFG | 1 | 0 | |

| Non-diabetes/IGT/IFG with elevated 1 h glucose levels* | 8 | 5 | |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.39 (5.31 to 5.47) | 5.39 (5.31 to 5.47) | 0.635 |

| HOMA-β | 72.5 (59.0 to 86.0) | 103 (87.2 to 119.6) | 0.001 |

| HOMA-IR | 1.4 (1.14 to 1.69) | 1.6 (1.29 to 1.90) | 0.477 |

| Variable during OGTT | |||

| Insulinogenic index | 1.1 (0.64 to 1.60) | 1.4 (1.18 to 1.71) | 0.002 |

| GlucoseAUC (mmol/l × h) | 18.8 (17.9 to 19.7) | 18.2 (17.3 to 19.0) | 0.089 |

| InsulinAUC (μU/ml × h) | 135.3 (98.7 to 171.9) | 145.1 (121.7 to 168.6) | 0.052 |

| Reactive hypoglycaemia | 17 (40) | 17 (25) | 0.079 |

Defined as 1 h glucose levels >8.6 mmol/l.

HbA1c, haemoglobin A1c; HOMA-IR, homeostasis model of assessment for insulin resistance; HOMA-β, homeostasis model of assessment for beta cell; IFG, impaired fasting glycaemia; IGT, impaired glucose tolerance; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test.

Data are expressed as mean (95% CI) or n (%).

We evaluated the associations between gender and the variables of glucose metabolism by multiple linear regression analysis. Adjustments were made for family history of diabetes within the second degree, BMI, gestational age, birth weight and SGA/AGA. In this analysis, male gender had inverse associations with HOMA-β (β −0.336, 95% CI −0.509 to −0.163, p<0.001) and insulinogenic index (β −0.195, 95% CI −0.344 to −0.047, p=0.01). GlucoseAUC during OGTT tended to be positively associated with male gender (β 0.056, 95% CI −0.0047 to 0.116, p=0.071).

In male subjects, after an adjustment for family history of diabetes, BMI, gestational age and birth weight, the logistic regression analysis showed that SGA was a statistically significant independent factor associated with hyperglycaemia (OR 33.3, 95% CI 1.67 to 662.6, p=0.022).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study assessing the glucose regulation in young adults with VLBW in an Asian population. Our study has indicated that 19% of young adults with VLBW already had hyperglycaemia: type 2 diabetes, IGT, IFG and non-diabetes/IGT/IFG with high 1 h plasma glucose level. A report from the Japanese Ministry of Health, Welfare, and Labour in 2007 showed that of 204 general young adults (aged 20–29 years), two individuals (0.98%) had high levels of HbA1c (>6.0%; NGSP equivalent values),18 while 3.6% of young adults with VLBW had the HbA1c values >6.0% in the present study. In a previous study, Hovi et al9 reported that VLBW infants in young adulthood had higher indexes of glucose intolerance compared with term infants. A recent epidemiological study has also shown that preterm birth is associated with an increased risk of diabetes in young adults.8 On the other hand, a study in the Netherlands showed that preterm birth was not associated with reduced insulin sensitivity in young adulthood.19 The findings of that study may be biased by the way of recruiting the control subjects born at term. Our findings would be in line with the standpoint of high prevalence of hyperglycaemia in premature infants in young adulthood, although absence of control subjects presents a limitation of demonstrating the impact of VLBW itself on glucose regulation.

We have also found that male subjects had higher glucose levels during OGTT than females. Previous studies in the general population showed that women had higher postload glucose levels than men, which were explained by differences in body size.20 21 During standard 75 g OGTT, men and women take the same amount of glucose, which is thought to be high dosage for women relative to their body size. In our study, however, men had significantly higher levels of both fasting and postload glucose concentrations during OGTT. Moreover, male gender was associated with lower β cell function and the risk of glucose intolerance. These findings might indicate that men with VLBW are more predisposed to diabetes than women; indeed, recent studies have shown that male premature infants are more vulnerable than females.22–27 In particular, the male sex is associated with various adverse outcomes including death,25 27 respiratory dysfunction,22 intraventricular haemorrhage,24 autism spectrum23 and neurodevelopmental impairment.26 Interestingly, in the present study, the mean value of height (155 cm) in women with VLBW is close to the average value of the Japanese female population (158 cm), whereas men with VLBW (164 cm) were found to be shorter compared with the Japanese male population (171 cm) (average height data of Japanese population were drawn from the report by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology in Japan).28 In a previous study, young adults who had been born SGA were shorter and had higher glucose levels than those with a normal birth weight.29 Reduced final height might be long-term consequences of intrauterine retardation, which would also influence glucose regulation. Further investigation is needed to clarify whether the influence of VLBW on physical growth is more remarkable in male than in female infants and elucidate the relationship between physical growth and glucose regulation.

Previous studies have shown that SGA itself is associated with glucose intolerance.30 In our study, SGA was not significantly associated with hyperglycaemia in total subjects but was associated in male subjects. The influence of SGA on glucose regulation in young adults with VLBW might be stronger in males than in females. It is possible that this gender difference in glucose regulation is owing to the gender difference in the strength of SGA effect.

Strength and weakness of the study

The major strength of our study is a well-characterised cohort of subjects with VLBW, who are quite rare in the general population (approximately 0.5% in this generation).31 Our study includes a relatively large number of young adults with VLBW, and the individuals with profound complications were carefully excluded in the recruiting process. In addition, as participants in the cohort were all Japanese, their racial homogeneity made considerations of ethnic differences in glucose regulation unnecessary. To date, the glucose regulation of Asian young adults with VLBW has been uncertain. Our findings would be useful to clinicians and researchers and stimulate future large-scale prospective cohort studies in Asian populations.

In the present study, we could not obtain information regarding the growth rate in childhood of all participants. This is a major limitation of the study. The postnatal growth pattern in infancy has been shown to be associated with later glucose intolerance.32–35 The clinical records of participants were written 20–30 years ago, and some of them were no longer preserved. Additionally, maternal factors such as advanced age, smoking, gestational diabetes, and perinatal complications were not available in the present study. These factors might have affected fetal malnutrition and subsequently led to VLBW. In terms of subjects in the present study, our study has no control subjects, presenting a limitation of demonstrating the impact of VLBW itself on glucose regulation. Another concern of the study is selection bias. Of 301 VLBW subjects who were thought to receive the invitation letters, 111 subjects (37%) participated in the study. The findings should be carefully interpreted taking into account the possibility that the participants might not be representative of general young adults with VLBW.

Future perspective

As neonatal intensive care is making steady progress, an increasing number of young adults with VLBW worldwide will face a greater variety of health problems. Clinician should be aware of the risk of hyperglycaemia in young adults with VLBW and follow-up them for a longer period of time. It may be worthwhile for them to check their glucose metabolism with OGTT in their 20s or 30s, which would lead to early intervention in their lifestyle and subsequently contribute to prevention of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease.5–7 In the present study, we have found that male gender was a significant independent risk factor of hyperglycaemia in young adults with VLBW. In addition to the gender difference, future studies are required to focus on the factors affecting the glucose metabolism in VLBW infants.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the participants in this study; the paediatricians who have treated the participants in their neonatal periods; the colleagues who made a great contribution to the study as clinical research coordinators: Masahiro Asano, Kikuko Tejima, Emiko Morita, Mari Suzuki, Kaoru Kikuchi and Chieko Suzuki; the colleagues who played vital roles by excellent technical assistance: Hiromi Kajima, Takako Akiyama and Masato Shouji; and Keisuke Ishii and Gregory O'Dowd for encouraging advice on the present study.

Footnotes

To cite: Sato R, Watanabe H, Shirai K, et al. A cross-sectional study of glucose regulation in young adults with very low birth weight: impact of male gender on hyperglycaemia. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000327. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000327

Contributors: RS and HW drafted the paper. RS conceived the study. RS and KS developed the idea. RS, HW, KS, SO, RG, MM and HN were involved in study design. RS and KS participated in data acquisition. RS, HW, HM, EI, MT and MM were engaged in data analysis. All the authors contributed to the interpretation of the findings. All the authors were involved in the revision and approved the final version.

Funding: This study was partly supported by grants from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (21390180) and from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare in Japan (H23-Cardiovascular disease and Diabetes-011).

Correction notice: This article replaces a previously published version. The tables in figure 2 have been removed.

Competing interests: None.

Ethical approval: The study was approved by the ethical committee of Seirei Hamamatsu General Hospital. All participants provided written informed consent to participate in the study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data will not be publically accessible. However, interested individuals may contact the authors.

References

- 1.Field DJ, Dorling JS, Manktelow BN, et al. Survival of extremely premature babies in a geographically defined population: prospective cohort study of 1994-9 compared with 2000-5. BMJ 2008;336:1221–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barker DJ, Gluckman PD, Godfrey KM, et al. Fetal nutrition and cardiovascular disease in adult life. Lancet 1993;341:938–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaijser M, Bonamy AK, Akre O, et al. Perinatal risk factors for diabetes in later life. Diabetes 2009;58:523–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whincup PH, Kaye SJ, Owen CG, et al. Birth weight and risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. JAMA 2008;300:2886–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med 2002;346:393–403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eriksson KF, Lindgarde F. Prevention of type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus by diet and physical exercise. The 6-year Malmo feasibility study. Diabetologia 1991;34:891–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tuomilehto J, Lindstrom J, Eriksson JG, et al. Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med 2001;344:1343–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crump C, Winkleby MA, Sundquist K, et al. Risk of diabetes among young adults born preterm in Sweden. Diabetes Care 2011;34:1109–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hovi P, Andersson S, Eriksson JG, et al. Glucose regulation in young adults with very low birth weight. N Engl J Med 2007;356:2053–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The study group of the Health Ministry in Japan Fetal Growth Curves of Japanese. Tokyo: The Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare, 1994:61 [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization Definition, Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus and Its Complications. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abdul-Ghani MA, Abdul-Ghani T, Ali N, et al. One-hour plasma glucose concentration and the metabolic syndrome identify subjects at high risk for future type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2008;31:1650–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Succurro E, Marini MA, Arturi F, et al. Elevated one-hour post-load plasma glucose levels identifies subjects with normal glucose tolerance but early carotid atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 2009;207:245–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zammitt NN, Frier BM. Hypoglycemia in type 2 diabetes: pathophysiology, frequency, and effects of different treatment modalities. Diabetes Care 2005;28:2948–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The Committee of Japan Diabetes Society on the diagnostic criteria of diabetes mellitus Report of the Committee on the classification and diagnostic criteria of diabetes mellitus. J Japan Diab Soc 2010;53:450–67 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, et al. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia 1985;28:412–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsuo S, Imai E, Horio M, et al. Revised equations for estimated GFR from serum creatinine in Japan. Am J Kidney Dis 2009;53:982–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.The Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare The National Health and Nutrition Survey in Japan. Tokyo: Daiichi-shuppan Publishing Company, 2007:187 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Willemsen RH, Leunissen RW, Stijnen T, et al. Prematurity is not associated with reduced insulin sensitivity in adulthood. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009;94:1695–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Faerch K, Borch-Johnsen K, Vaag A, et al. Sex differences in glucose levels: a consequence of physiology or methodological convenience? The Inter99 study. Diabetologia 2010;53:858–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sicree RA, Zimmet PZ, Dunstan DW, et al. Differences in height explain gender differences in the response to the oral glucose tolerance test- the AusDiab study. Diabet Med 2008;25:296–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henderson-Smart DJ, Hutchinson JL, Donoghue DA, et al. Prenatal predictors of chronic lung disease in very preterm infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2006;91:F40–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson S, Hollis C, Kochhar P, et al. Autism spectrum disorders in extremely preterm children. J Pediatr 2010;156:525–31.e2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mohamed MA, Aly H. Male gender is associated with intraventricular hemorrhage. Pediatrics 2010;125:e333–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morse SB, Wu SS, Ma C, et al. Racial and gender differences in the viability of extremely low birth weight infants: a population-based study. Pediatrics 2006;117:e106–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spinillo A, Montanari L, Gardella B, et al. Infant sex, obstetric risk factors, and 2-year neurodevelopmental outcome among preterm infants. Dev Med Child Neurol 2009;51:518–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tyson JE, Parikh NA, Langer J, et al. Intensive care for extreme prematurity—moving beyond gestational age. N Engl J Med 2008;358:1672–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.The Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology in Japan A Report of School Health Statistics. Tokyo: National Printing Bureau, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leger J, Levy-Marchal C, Bloch J, et al. Reduced final height and indications for insulin resistance in 20 year olds born small for gestational age: regional cohort study. BMJ 1997;315:341–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saenger P, Czernichow P, Hughes I, et al. Small for gestational age: short stature and beyond. Endocr Rev 2007;28:219–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vital Statistics The Statistics and Information Department, Minister's Secretariat, Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare. Vol. 1 Japan: Vital Statistics, 2009:124–7 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crowther NJ, Cameron N, Trusler J, et al. Influence of catch-up growth on glucose tolerance and beta-cell function in 7-year-old children: results from the birth to twenty study. Pediatrics 2008;121:e1715–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eriksson JG, Osmond C, Kajantie E, et al. Patterns of growth among children who later develop type 2 diabetes or its risk factors. Diabetologia 2006;49:2853–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Finken MJ, Keijzer-Veen MG, Dekker FW, et al. Preterm birth and later insulin resistance: effects of birth weight and postnatal growth in a population based longitudinal study from birth into adult life. Diabetologia 2006;49:478–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leunissen RW, Kerkhof GF, Stijnen T, et al. Timing and tempo of first-year rapid growth in relation to cardiovascular and metabolic risk profile in early adulthood. JAMA 2009;301:2234–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.