Abstract

Introduction

WHO case management algorithm for paediatric pneumonia relies solely on symptoms of shortness of breath or cough and tachypnoea for treatment and has poor diagnostic specificity, tends to increase antibiotic resistance. Alternatives, including oxygen saturation measurement, chest ultrasound and chest auscultation, exist but with potential disadvantages. Electronic auscultation has potential for improved detection of paediatric pneumonia but has yet to be standardised. The authors aim to investigate the use of electronic auscultation to improve the specificity of the current WHO algorithm in developing countries.

Methods

This study is designed to test the hypothesis that pulmonary pathology can be differentiated from normal using computerised lung sound analysis (CLSA). The authors will record lung sounds from 600 children aged ≤5 years, 100 each with consolidative pneumonia, diffuse interstitial pneumonia, asthma, bronchiolitis, upper respiratory infections and normal lungs at a children's hospital in Lima, Peru. The authors will compare CLSA with the WHO algorithm and other detection approaches, including physical exam findings, chest ultrasound and microbiologic testing to construct an improved algorithm for pneumonia diagnosis.

Discussion

This study will develop standardised methods for electronic auscultation and chest ultrasound and compare their utility for detection of pneumonia to standard approaches. Utilising signal processing techniques, the authors aim to characterise lung sounds and through machine learning, develop a classification system to distinguish pathologic sounds. Data will allow a better understanding of the benefits and limitations of novel diagnostic techniques in paediatric pneumonia.

Article summary

Article focus

We seek to characterise lung sounds associated with different respiratory illnesses in children using electronic auscultation and determine whether these sounds can be differentiated from normal through computerised lung sound analysis.

We summarise the study design and methods with standardised protocols for electronic auscultation and chest ultrasound in children.

Key message

We aim to develop a protocol for increased specificity of paediatric pneumonia diagnosis in developing countries.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Our study is limited by the case definitions available. With no gold standard for many paediatric respiratory diseases, we will rely on clinical exam findings and chest radiography.

By investigating a number of novel and commonly used diagnostic tools for a variety of respiratory diseases in children, we will gain valuable information regarding the diagnostic potential of each, with a main focus on the electronic stethoscope.

Introduction

Acute lower respiratory infection (ALRI) is the leading cause of death in children under 5 years of age. Pneumonia alone is responsible for killing 1.6 million children worldwide. WHO developed a case management algorithm that relies solely on symptoms of shortness of breath or cough, an elevated respiratory rate and chest indrawing for the diagnosis of pneumonia and administration of antibiotics and/or referral in resource-poor areas (table 1). Where successfully implemented, this algorithm has resulted in a 30%–40% reduction in case mortality1 but has moderate sensitivity and poor specificity, ranging from 16% for children presenting with wheeze2 and 49% for non-severe pneumonia to 95% for very severe pneumonia.3 Hazir and colleagues demonstrated that over 80% of children with WHO-defined non-severe pneumonia had normal chest radiographs (CXR)4 and that the resulting case management was equivalent to no treatment in a randomised clinical trial,5 only further increasing concern for global antibiotic resistance.

Table 1.

WHO classification of acute lower respiratory infection in children presenting with cough and/or difficult breathing

| Number of pneumonia (cough and cold) |

|

| Non-severe pneumonia |

|

| Severe pneumonia | Lower chest indrawing ± rapid breathing |

| Very severe pneumonia | At least one of the following:

|

Pneumonia is a pathological process resulting in fluid-filled alveoli, and while there are multiple potential aetiologies, most are infectious. Currently, there is no gold standard for detection of bacterial pneumonia requiring treatment. In areas where resources are readily available, chest radiography and clinical diagnosis serve as the standard of care for pneumonia detection, but these are not available in resource-poor settings around the world. Potential alternatives exist within aspects of the physical exam and imaging. Supplementing oxygen saturation measurements with the current WHO algorithm has been shown to increase specificity6; however, the normal range in healthy children varies with environmental factors like altitude.7 Another promising alternative for detection of paediatric pneumonia is lung ultrasound. Ultrasound has the advantage of gathering information from multiple angles and the ability to detect air-fluid differences that are present with pneumonia. Studies suggest that this technique may be more sensitive than radiography and has the added benefit of lack of radiation; however, these studies have all lacked power due to small sample size.8–13 Cost and availability of skilled ultrasound technicians may limit use in resource-poor settings. Chest auscultation is a valuable tool for detection of respiratory pathology and is used widely in clinical practice. However, limitations include inter-listener variability, subjectivity in the interpretation of lung sounds14 15 and lack of trained personnel in resource-poor settings. Electronic auscultation has the advantage of signal amplification and ambient noise reduction leading to increased signal-to-noise ratio along with its independence on human ear sensitivity to different acoustic frequencies. Furthermore, through computerised lung sound analysis (CLSA), this diagnostic method results in discrete values from a final reading, thereby facilitating standardisation. With advancement in electronic stethoscopes and CLSA, there is great potential for improved diagnosis of paediatric pneumonia where multiple diagnostic tools are not readily available.

In acoustic signal processing, the two commonly studied lung sounds are crackles and wheezes, which constitute unique temporal and frequency characteristics. Crackles have been most commonly associated with pneumonia, whereas wheezes are often observed in patients with asthma and bronchiolitis.16 According to the Computerised Respiratory Sound Analysis Guidelines,17 the frequency of crackles is characterised in the spectrum of 200–2000 Hz, while wheezes have a frequency spectrum of 100–1000 Hz. Wheezes have continuous waveforms (>100 ms duration) with one or more tonal components and a dominant frequency >400 Hz during the expiratory phase. Crackles are short (<20 ms) non-periodic waveforms with transitory sharp peaks and broadband frequency content during mid-inspiratory phase. Time–frequency decomposition of lung sounds provides useful information in identifying and localising adventitious lung sounds in a patient.

Translating the CLSA characterisation of abnormal lung sounds to clinical practice has yet to be achieved. There are a few studies demonstrating potential, yet data are largely lacking, especially in the field of paediatrics. Our group conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies using CLSA for the detection of a variety of respiratory disease in adults, which found an overall sensitivity and specificity of 80% and 85%, respectively, when compared with radiologically confirmed cases, with markedly limited results due to lack of quality and quantity of available data, as well as lack of standardisation.16 18–22

In this study, we seek to use electronic auscultation to record lung sounds of children with various clinical diagnoses, pneumonia (diffuse interstitial and lobar), asthma, bronchiolitis and upper respiratory infection (URI) in a tertiary care centre in Lima, Peru, and determine whether they can be differentiated from normal lung sounds using CLSA. In addition, we aim to compare with imaging modalities of chest radiography and ultrasound. We hypothesise that not only will the sounds profiles of each pulmonary disease pathology differ from normal, but due to unique characteristics of lung sounds associated with bacterial pneumonia versus asthma, bronchiolitis or URI, CLSA may allow differentiation of various acute lower respiratory disease processes. With this information in conjunction with additional basic clinical information (ie, temperature, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation), we believe that a much needed improvement in the detection and case management of paediatric pneumonia is possible.

Methods

Study objectives

The primary objectives of this study are to characterise lung sounds associated with various clinical diagnoses, radiologically confirmed consolidative pneumonia and diffuse interstitial pneumonia, bronchiolitis, asthma and URIs, in a paediatric population, and to determine if these diagnoses can be differentiated from normal through automated lung sounds analysis and compare with modalities of imaging, current WHO algorithm for ALRI case management and microbiological testing. We then aim to develop a clinical protocol pairing electronic auscultation with a CLSA algorithm to aid in pneumonia diagnosis.

Study design

Our design will be a cross-sectional study of lung sounds and other diagnostic modalities from children 2 to 60 months of age presenting with a primary respiratory complaint to the Instituto Nacional de Salud del Niño, a tertiary care hospital in Lima, Peru. Informed consent from parents will be obtained in the emergency department (ED), asthma ward or pulmonary ward where all testing will be performed in a single visit. Parents will be asked to fill out a questionnaire, while the physician reports relevant aspects of the physical exam. Electronic auscultation will then be performed, following by imaging and collection of blood, respiratory, urine and stool samples.

During the initial phase, we will record lung sounds from 600 children from 2 to 59 months of age, 100 each with consolidative pneumonia, diffuse interstitial pneumonia, asthma, bronchiolitis, URIs and normal lungs. The second phase will consist of completing our testing set for external validity and comparing CLSA with the current WHO algorithm and other diagnostic tools such as physical exam findings, chest ultrasound and microbiologic testing in order to construct an improved algorithm for pneumonia diagnosis.

Study population

Children from 2 to 59 months of age presenting to the ED or in the asthma or pulmonary ward without a history of chronic lung disease, excluding asthma, or significant cardiac disease will be invited to participate in the study. Children with respiratory complaints will be invited to participate as potential cases, while those without respiratory complaints and no acute respiratory illness within 1 month of presentation will be invited to join the study as controls.

Children will be considered eligible if their parents or guardians are able to provide written informed consent, and they themselves do not require airway management or non-invasive ventilation. Children will be considered ineligible if they have chronic lung diseases other than asthma, such as cystic fibrosis, bronchiectasis and chronic lung disease of prematurity, or significant congenital heart disease. Patients will be considered ineligible post-consent if they were found to have more than one active respiratory diagnosis upon further testing. Group classification also may be modified post-consent and further enrolment required depending on chest x-ray (CXR) final readings and microbiological testing for diagnosis.

Outcomes and case definitions

Because there is no gold standard for diagnosis, we aim to compare our results with common case definitions and clinical diagnoses by experienced physicians. Secondary outcomes will incorporate aetiology information from standard culture and molecular techniques; however, these additional data will not serve as the gold standard.

Pneumonia will be initially categorised upon clinical diagnosis by examining paediatricians at El Instituto Nacional de Salud del Niño and further characterised as consolidative or diffuse interstitial pneumonia given final CXR reading by blinded radiologists from the Johns Hopkins University. Asthma will be defined by the presence of wheeze on physical exam, history of asthma and improvement with bronchodilators. Bronchiolitis will be defined as the presence of wheeze and difficulty breathing on physical exam and viral symptoms (cough, rhinorrhoea), no history of asthma and little or no improvement with bronchodilators if attempted. URI will be defined as respiration rate <50 breaths per minute and associated with one or more of the following: clear nasal secretions, sore or red throat or hoarseness.

Sample size

Our recruitment goal is 600 subjects, 100 each with consolidative pneumonia, diffuse interstitial pneumonia, asthma, bronchiolitis, URI and normal lungs. Sample size was powered to improve specificity of WHO algorithm upon the addition of electronic auscultation. To detect an improvement in diagnostic specificity from 50% (WHO algorithm for paediatric pneumonia) to 80% (CLSA and WHO algorithm) with 95% power and α of 0.05 between pneumonia and non-pneumonia cases, we require 70 patients per group in the training set. We will also recruit a test set consisting of an additional 30 patients per group (30% of total sample) to estimate areas under the curve for our diagnostic algorithm. Each group will be over-enrolled by 20 to account for post-consent ineligibility, for a total of 720.

Study organisation

A.B. PRISMA in Lima, Peru, and Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, USA, will provide administrative oversight for the study. There will be a research coordinator at a central location in Lima, Peru, who will provide logistical support and management of the study team. Instituto Nacional de Salud del Niño will provide a team of study nurses and physicians to carry out recruitment, physical examination and collection of specimens. We have also established prior training by an experienced ultrasonographer to conduct chest ultrasonography. A multidisciplinary team of clinicians, field epidemiologists, acoustical engineers and biostatisticians from Johns Hopkins University, Tufts University, Cincinnati Children's Hospital and Instituto Nacional de Salud del Niño will be involved with study design and conduct, statistical analysis and reporting of results.

Questionnaire

We will ask the parent or guardian about the child's past medical history, environmental exposures, access to healthcare and current respiratory symptoms. We will enquire about demographic information, nutrition and vaccination history. We will ask about co-morbidities, family history and developmental history. Environmental questions pertained to housing, number of children, rural versus urban living, parent occupations, smoke and allergen exposure, and sick contacts. Current respiratory symptoms were asked of the parent or guardian to answer subjectively and included rapid breathing, difficulty breathing, chest indrawing, cyanosis, cough, sputum production, audible breath sounds and subjective fever.

Physical exam and laboratory testing

The initial set of vital signs will be recorded, including pulse oximetry. During the physical exam, a single examining physician from the larger group of study physicians will be responsible for recording findings for a given patient with emphasis on the respiratory exam. Chest retractions, nasal flaring, grunting, stridor and accessory muscle use will be noted and characterised if present, along with any adventitious lung sounds appreciated by physician and study team member on chest auscultation. Degree of improvement after bronchodilators will also be recorded if administered. Additionally, signs of dehydration and malnutrition will be reported if present. Laboratory results will be recorded if evaluated by the ED and include complete blood count, electrolytes and arterial blood gas.

Electronic auscultation

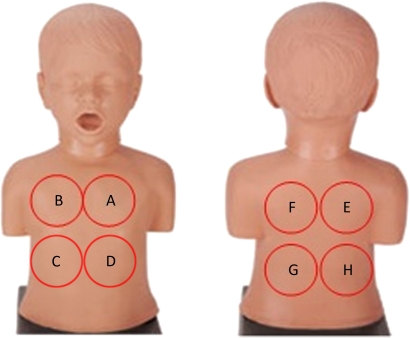

Parents will be allowed to position the patient supine or upright. The study team member will listen to eight auscultation sites using a ThinkLabs ds32a Digital Stethoscope and mp3 recorder, for 10 s at each site, in the following order of placement: front top left and right, fronterolateral bottom right and left, back top right and left and back bottom left and right (figure 1). Auscultation will be performed at the participant's normal breathing patterns during recording without being asked to take deep breaths. We will allow only one repeat of auscultation if recording is interrupted for any reason or due to unacceptable signal quality of the first recording.

Figure 1.

Order of auscultation by electronic stethoscope. The study team member will listen to each site, starting with ‘A’ for 10 s each.

Lung ultrasound

All participants will receive bilateral lung ultrasonography carried out on SonoSite portable ultrasound machine with HFL38/13–6 MHz and P17/5–1 MHz MicroMaxx® transducers by a single ultrasound technician who has been trained to the standardised protocol. Patients will be examined in the supine position with each hemithorax divided into six sections: two anterior, two lateral and two posterior. The posterior area is defined from the posterior axillary line to the paravertebral line. Longitudinal and oblique scans will be obtained at each of the chest zones. Longitudinal scans allow visualisation of the ribs with the pleural line under them.23 Representative images from each section will be saved and later transferred to radiologists at an outside institution.

To assess for pneumonia, two of three radiologists must agree on the description of ultrasound images compatible with pneumonia. Consolidation will be determined by (1) the presence of hypo- or anechoic images with loss of distinct pleural lines and (2) an irregular shredded border of the pleural line that is distinct from the lung line, termed the ‘shred sign’. Additional signs to be reported will include punctate hyperechoic images reflecting air bronchograms, decreased lung sliding and homogeneous hypoechoic images in the pleural space corresponding to pleural effusions. Interstitial infiltrates will be determined by the presence of ‘lung rockets’, which correlate to three or more B-lines in a longitudinal view between two ribs. Additional features to be reported include heterogeneous echotexture, air and fluid bronchograms, lung pulse and additional B-lines.23

Chest radiography

All case participants will undergo chest radiography. We will attempt postero-anterior and lateral films but will allow an antero-posterior view if not possible. Digital images will be sent to a third party reading group blinded to clinical information. Using WHO standardisation of CXR interpretation for paediatric pneumonia,24 25 radiologists will comment on quality as adequate, suboptimal or unreadable and on the presence of pathology as consolidative or interstitial with or without pleural effusions. Radiographic evidence of pneumonia will be confirmed by agreement by two of three radiologist reports for a given patient. Additional pathologic findings not previously characterised will also be recorded and reported to the patient's physician for further intervention if necessary.

Microbiological studies

Blood, urine and nasopharyngeal samples will be collected according to our study design (figure 2). Blood samples will be drawn for cultures and sensitivities. Urine will be tested for detection of pneumococcal antigen and stored for PCR. Nasopharyngeal swabs will be tested for respiratory viruses, along with culture and sensitivities. Respiratory pathogens tested by PCR will include Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae and respiratory syncytial virus.

Figure 2.

Microbiology testing schematic.

Safety

To ensure safety, the researcher collecting data is experienced with providing care to children. The researcher will use this experience to minimise any discomfort the children may have. All blood samples will be collected by a skilled nurse or phlebotomist.

We will adhere to hospital procedures for avoiding hospital-acquired infections. We will wash hands with soap and water or alcohol-based hand sanitizer before patient contact. We will wear gloves, gowns and mask when required. We will clean the devices using alcohol swabs before and after each use.

Data quality and management

Prior to data collection, a Manual of Operations will be developed to ensure standardisation and reliability and contain detailed instructions for all study procedures and guidelines for data collection. The manual will be revised as needed and distributed to members of the study team.

All data are recorded first on paper case report forms and subsequently double entered using Microsoft ACCESS. Data sets will be cross validated and errors corrected. Electronic lung recordings will be transferred from the mp3 player to participant-specific files on the study computer at least every other day and backed-up weekly. Digital CXR images will also be uploaded to these files and backed-up similarly.

Analysis of lung sounds and statistics

An important first step in CLSA is using common signal processing techniques to investigate high- and low-frequency information using methods such as the Short-time Fourier Transform, wavelet transforms and P-spline bases. The second step will be extracting signal processing features to train the classifier.

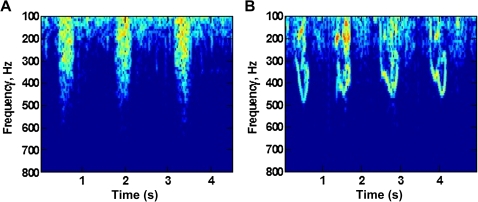

Based on preliminary recordings to date performed by our group in Baltimore (figure 3), we anticipate that wheeze can be characterised using features from the Fourier transform, such as the existence and temporal stability of tonal peaks in the 300–1000 Hz range, while crackles could be recognised using features such as amplitude, the presence of broadband energy and the duration of this energy. Features such as the decrease in signal energy with frequency can characterise movement sounds. We have previously used time–frequency descriptors such as Mel-frequency cepstral coefficients as features and anticipate they will be useful for CLSA but may require temporal information as well. We will use the extracted features from signal processing analyses for classification using machine learning algorithms including: nearest neighbour methods, support vector machines, random forests and gradient boosting. Primary analysis will consist of a fivefold cross validation on the training set to calculate expected prediction errors. The training set will additionally be used to estimate areas under the curve for our diagnostic algorithm, including CLSA, WHO algorithm, imaging and physical exam findings. Secondary analysis will include calculating sensitivities and specificities of experimental diagnostic ultrasound for detection of pneumonia when compared with gold standards (clinical diagnosis and CXR reading). Performance will be measured using logistic and multinomial regression, receiver operating characteristic curves and area under the curve.

Figure 3.

Preliminary data suggest a difference in spectral analysis between children with and without wheeze. Short-time Fourier Transform analysis was used to visualise spectrograms of a normal control (A) and asthmatic child with active wheeze (B). Representative sample is from preliminary recordings taken from the Emergency Room at the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland.

Discussion

This study aims to investigate alternatives to improve the specificity of WHO algorithm for paediatric pneumonia, namely electronic auscultation and chest ultrasonography. Utilising electronic auscultation, we intend to characterise and analyse lung sounds associated with consolidative pneumonia, diffuse interstitial pneumonia, bronchiolitis, asthma and URIs to determine if these diagnoses can be differentiated from normal through automated lung sounds and to compare with chest ultrasound, WHO algorithm and molecular testing for aetiology. By reporting a protocol for CLSA, we hope to encourage standardisation and expansion of recorded lung sounds via an online library for continued enhancement of machine learning as well as for continued scientific research and clinical education.

We foresee our greatest challenge in maximising the quality of recorded lung sounds. To begin the study, we will use a commercial electronic stethoscope for recordings, which is identical in design to standard clinical stethoscopes. However, through sound processing using time–frequency analysis methods such as the Short-time Fourier Transform and Continuous Wavelet Transforms, we hope to enhance the signal-to-noise ratio for data analysis and characterisation. By examining additional features such as amplitude, we may also be better able to identify crackles and consolidation. We also plan to test alternative recording devices using piezoelectric microphones covered with a thin polymer that may be able to better capture lung sounds. Based on our recordings to date, we anticipate that wheeze can be differentiated from normal breath using features such as the existence and temporal stability of tonal peaks in the 300–1000 Hz range, while crackle should be recognisable using features such as the presence of broadband energy and the duration of this energy. Features such as the decrease in signal energy with frequency can characterise movement sounds. We have previously used time–frequency descriptors borrowed from speech processing (Mel-frequency cepstral coefficients and their time derivatives) and cough-specific time-domain features such as signal rise time and event duration and anticipate they will be useful for CLSA. We will use the extracted features from signal processing analyses for classification using machine learning algorithms such as nearest neighbour methods, support vector machines or random forests.

The largest challenge in regards to lung ultrasound will likely be obtaining adequate quality of images and inter-user variability. To reduce variability, the study technician will be trained to systematically scan each subdivided hemithorax for pathologic findings described previously,9 23 and if possible, we will attempt lung ultrasound twice for each patient. Ultrasound also takes substantially longer compared with chest radiography because all areas must be adequately explored; therefore, it may be difficult for a child to be cooperative for that length of time. Through our large sample size and detailed methods, we aim to improve standardisation of paediatric chest ultrasound and further define pathologic findings associated with disease, which may also lead to more efficient and faster scanning.

Limitations to this study centre mostly on our case definitions for clinical diagnoses. As mentioned previously, there are no precise gold standards and as with many paediatric diseases, diagnosis is clinical. As such, our end points are determined by clinical exam findings by single examining physicians with additional confirmation via radiology for pneumonia cases only. We acknowledge the variability of observed findings among physicians and accept that this is the mechanism of diagnosis in most clinical settings.

WHO algorithm for case management of paediatric pneumonia lacks diagnostic specificity. While clinical information such as elevated heart rate and decreased oxygen saturation may aid in degree of illness and monitoring, these data also lack specificity required to drastically improve case management. Lung ultrasound is also a promising tool and offers portability that is not available for radiography. Ultrasound has the added benefit of pleural effusion detection, which may prove an important adjunct to the electronic auscultation algorithm. However, cost and availability of skilled technicians may greatly hamper its utility in resource-poor settings, similar to microbiologic testing. Electronic auscultation is a simple inexpensive tool that could have great diagnostic impact on ALRI in children worldwide. Through further research, we foresee utilising this tool with pre-programmed computerised analysis to improve case management in developing countries.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

To cite: Ellington LE, Gilman RH, Tielsch JM, et al. Computerised lung sound analysis to improve the specificity of paediatric pneumonia diagnosis in resource-poor settings: protocol and methods for an observational study. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000506. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000506

Funding: Funding for this study and support for LEE was provided by the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation Clinical Research Fellowship. Additional support came from A.B. PRISMA, Instituto Nacional de Salud del Niño and collaborators at JHU, Tufts University, Cincinnati Children's Hospital and Hospital Nacional Rebagliati. Thinklabs Medical (Centennial, Colorado) generously provided us with an electronic stethoscope, at discount.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Approval was obtained from the Ethics Committees of A.B. PRISMA, Instituto Nacional de Salud del Niño and Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. Dissemination will include publications following the study and the development of a free online library of lung sounds for improvement of CLSA, future research and clinical education.

Contributors: All authors were involved in the study design and writing of the manuscript, and all reviewed the final manuscript before submission. LEE directly contributed to study design and is responsible for supervision of data gathering at the children's hospital in Lima, electronic auscultation and chest ultrasound recordings, data management, analysis and writing of this manuscript. RHG provided mentorship to LEE and technical support for the study. JMT and MS contributed to the concept and study design. DF will serve as study physician, provide supervision and administrative oversight on site and perform physical testing. SR contributed to study design and was responsible for developing and training the study technician to a standardised chest ultrasound protocol. BC contributed to study design and will contribute to statistical analysis. BT, ME and JW contributed to study design and will contribute significantly to signal processing and data analysis. WC had ultimate oversight over study design and administration and was equally responsible in writing of the manuscript and serves as mentor to LEE throughout the conduct of the study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Currently, no unpublished data are available. Plans for dissemination include final publication following completion of the study following the STARD guidelines for reporting diagnostic accuracy. We aim to develop a free online library of lung sounds for further enhancement of computerised lung sound analysis and the machine learning algorithm, as well as for future research and clinical education.

References

- 1.Sazawal S, Black RE. Effect of pneumonia case management on mortality in neonates, infants, and preschool children: a meta-analysis of community-based trials. Lancet Infect Dis 2003;3:547–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cardoso MR, Nascimento-Carvalho CM, Ferrero F, et al. Adding fever to WHO criteria for diagnosing pneumonia enhances the ability to identify pneumonia cases among wheezing children. Arch Dis Child 2011;96:58–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Puumalainen T, Quiambao B, Abucejo-Ladesma E, et al. Clinical case review: a method to improve identification of true clinical and radiographic pneumonia in children meeting the World Health Organization definition for pneumonia. BMC Infect Dis 2008;8:95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hazir T, Nisar YB, Qazi SA, et al. Chest radiography in children aged 2-59 months diagnosed with non-severe pneumonia as defined by World Health Organization: descriptive multicentre study in Pakistan. BMJ 2006;333:629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hazir T, Nisar YB, Abbasi S, et al. Comparison of oral amoxicillin with placebo for the treatment of world health organization-defined nonsevere pneumonia in children aged 2-59 months: a multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial in Pakistan. Clin Infect Dis 2011;52:293–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Madico G, Gilman RH, Jabra A, et al. The role of pulse oximetry: its use as an indicator of severe respiratory disease in Peruvian children living at sea level. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1995;149:1259–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schult S, Canelo-Aybar C. Oxygen saturation in healthy children aged 5 to 16 years residing in Huayllay, Peru at 4340 m. High Alt Med Biol 2011;12:89–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iuri D, De Candia A, Bazzocchi M. Evaluation of the lung in children with suspected pneumonia: usefulness of ultrasonography. Radiol Med 2009;114:321–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parlamento S, Copetti R, Di S. Evaluation of lung ultrasound for the diagnosis of pneumonia in the ED. Am J Emerg Med 2009;27:379–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang PC, Luh KT, Chang DB, et al. Ultrasonographic Evaluation of pulmonary consolidation. Am Rev Respir Dis 1992;146:757–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Su YH, Wang M, Block TM, et al. Transrenal DNA as a diagnostic tool: important technical notes. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2004;1022:81–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gehmacher O, Mathis G, Kopf A, et al. Ultrasound imaging of pneumonia. Ultrasound Med Biol 1995;21:1119–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lichtenstein D, Lascols N, Mezière G, et al. Ultrasound diagnosis of alveolar consolidation in the critically ill. Intensive Care Med 2004;30:276–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murphy R, Vyshedskiy A, Charnitsky V, et al. Automated lung sound analysis in patients with pneumonia. Respir Care 2004;49:1490–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grenier M, Gagnon K, Genest J, et al. Clinical comparison of acoustic and electronic stethoscopes and design of a new electronic stethoscope. Am J Cardiol 1998;81:653–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gurung A, Scrafford C, Tielsch J, et al. Computerized lung sound analysis as a diagnostic aid for the detection of abnormal lung sounds: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Respiratory Med 2011;105:1369–403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abaza AA, Day JB, Reynolds JS, et al. Classification of voluntary cough sound and airflow patterns for detecting abnormal pulmonary function. Cough 2009;5:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reichert S, Gass R, Brandt C, et al. Analysis of respiratory sounds: state of the art. Clin Med Circ Respirat Pulm Med 2008;2:45–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu X, Bahoura M. An integrated automated system for crackles extraction and classification. Biomed Signal Process Contr 2008;3:244–54 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marshall A, Boussakta S. Signal analysis of medical acoustics sounds with applications to chest medicine. J Franklin Inst 2007;344:230–42 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taplidou S, Hadjileontiadis L, Kitsas I, et al. On applying continuous wavelet transform in wheeze analysis. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2004;5:3832–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saeed S, Body R. Auscultating to diagnose pneumonia. Emerg Med J 2007;24:294–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Volpicelli G, Silva F, Radeos M. Real-time lung ultrasound for the diagnosis of alveolar consolidation and interstitial syndrome in the emergency department. Eur J Emerg Med 2010;17:63–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Standardization of Interpretation of Chest Radiographs for the Diagnosis of pneumonia in Children World Health Organization Pneumonia Vaccine Trial Investigators' Group DEPARTMENT OF VACCINES. World Health, 2001. http://www.who.int/vaccines-documents/ [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, et al. Towards complete and accurate reporting of studies of diagnostic accuracy: the STARD initiative. BMJ 2003;326:41–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.