Abstract

Objective

The primary objective was to evaluate the capacity of first-referral health facilities in Tanzania to perform basic surgical procedures. The intent was to assist in planning strategies for universal access to life-saving and disability-preventing surgical services.

Design

Cross-sectional survey.

Setting

First-referral health facilities in the United Republic of Tanzania.

Participants

48 health facilities.

Measures

The WHO Tool for Situational Analysis to Assess Emergency and Essential Surgical Care was employed to capture a health facility's capacity to perform basic surgical (including obstetrics and trauma) and anaesthesia interventions by investigating four categories of data: infrastructure, human resources, interventions available and equipment. The tool queried the availability of eight types of care providers, 35 surgical interventions and 67 items of equipment.

Results

The 48 facilities surveyed served 18.6 million residents (46% of the population). Supplies for basic airway management were inconsistently available. Only 42% had consistent access to oxygen, and only six functioning pulse oximeters were located in all facilities surveyed. 37.5% of facilities reported both consistent running water and electricity. While very basic interventions (suturing, wound debridement, incision and drainage) were provided in nearly all facilities, more advanced life-saving procedures including chest tube thoracostomy (30/48), open fracture management (29/48) and caesarean section delivery (32/48) were not consistently available.

Conclusions

Based on the results in this WHO country survey, significant gaps exist in the capacity for emergency and essential surgical services in Tanzania including deficits in human resources, essential equipment and infrastructure. The information in this survey will provide a foundation for evidence-based decisions in country-level policy regarding the allocation of resources and provision of emergency and essential surgical services.

Article summary

Article focus

On-site visits to primary health centres in a developing nation.

Evaluate capacity to deliver emergency and surgical care-identify gaps in equipment, skills and personnel.

Key messages

Basic surgical procedures are being performed in nearly all health centres.

Significant deficits in human resources, essential equipment and infrastructure.

Pulse oximetry is rarely available.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Most comprehensive evaluation of a developing country's surgical capacity.

Based on established well-accepted analysis tool.

Relies on subjective measures and estimate.

Introduction

Surgical services at the first-referral level are an essential component of comprehensive primary healthcare. Conditions that can be treated with surgery account for an estimated 11% of the world's disability-adjusted life years.1 Despite recent data estimating the global volume of surgery at 234 million surgical procedures annually and significant disparities between procedures performed in high- and low-income counties, global public health initiatives have traditionally neglected the necessity for the provision of surgical services.2 Poor access to surgical services, particularly at rural facilities, results in excess morbidity and mortality from a broad range of treatable surgical conditions including injuries, complications of pregnancy, sequelae of infectious diseases, acute abdominal conditions and congenital anomalies. Improving the access to surgical services in low-income countries requires a systems-based approach addressing gaps in infrastructure, trained/skilled personnel, appropriate equipment and medications.

Tanzania, similar to other sub-Saharan African countries, faces significant challenges in the provision of health services. Infant mortality is 68 per 1000 live births and maternal mortality rate is 578 per 100 000 live births.3 The leading causes of maternal death (haemorrhage, unsafe abortion, eclampsia and obstructed labour) can all be addressed with appropriate emergency obstetric care, which often require surgical and/or anaesthesia interventions. In a 1999 Tanzanian Ministry of Health and Social Welfare (MoHSW) census, health facilities numbered 4714 with 280 hospitals, 479 health centres and 3955 dispensaries for a total of 32 000 beds (1:896 people). There were 110 surgeons (1/3 in cities, 1/3 in administration and 1/3 emigrated) and 16 anaesthesiologists. Human resources for health were critically absent, with fewer than 1/3 of posts filled in primary hospitals.4

As funders and public health experts adopt the expansion of primary healthcare services, the inclusion of surgical services at the first-referral level is critical. The purpose of this survey was to collect knowledge gained from comprehensive quantitative assessments of surgical capacity in sub-Saharan African countries such as Tanzania in order to assist in planning strategies for universal access to life-saving and disability-preventing surgical services.

Materials and methods

The WHO Tool for Situational Analysis to Assess Emergency and Essential Surgical Care was developed as a comprehensive questionnaire to quantify the surgical capacity in a wide range of health facilities.5 This online tool captures a health facility's capacity to perform basic surgical (including obstetrics and trauma) and anaesthesia interventions by investigating four categories of data: infrastructure, human resources, interventions available and equipment. The tool queries the availability of eight types of care providers, 35 surgical interventions and 67 items of equipment.

WHO situation analysis tool to assess Emergency and Essential Surgical Care was completed at 48 health facilities representing 16 of 26 regions in Tanzania. The health facility data were obtained during site visits by representatives from the Tanzania MoHSW, WHO country office and members of Global Initiative for Emergency and Essential Surgical Care (GIEESC) between March 2009 and October 2010. Data on various indices were entered into and analysed from WHO Global DataCol Database for Emergency and Essential Surgical Care (table 1). Some results, such as the average distance travelled prior to admission, were expressed as a weighted mean to better reflect the distance travelled by the average patient seeking surgical care in the country. To calculate the weighted mean, we summed the products of annual admissions and average distance travelled for each facility and then divided by the sum of annual admissions for all facilities.

Table 1.

Results of Situational Analysis Tool

| C | I | N | |||

| General and congenital | |||||

| Blood bank | 29 | 48 | 23 | ||

| Personnel | Electricity | 44 | 52 | 4 | |

| General physician performing surgery | 113 | Emergency guidelines | 25 | 13 | 63 |

| Non-physicians performing surgery | 122 | Emergency room | 33 | 15 | 52 |

| Paramedics and midwives | 4017 | Generator | 58 | 2 | 40 |

| Physicians trained in surgery (specialist) | 64 | Haemoglobin and urine analysis | 96 | 4 | 0 |

| Medical records | 98 | 2 | 0 | ||

| Procedure | P | Running water | 56 | 35 | 8 |

| Appendectomy | 69 | Surgery guidelines | 58 | 6 | 35 |

| Biopsy | 81 | Cotton wool | 77 | 21 | 2 |

| Burn care | 90 | Adhesive tape | 96 | 4 | 0 |

| Cataract repair | 35 | Apron, plastic, reusable | 81 | 15 | 4 |

| Cleft lip repair | 25 | Bandages sterile | 98 | 2 | 0 |

| Congenital hernia repair | 71 | Batteries for flashlight | 58 | 33 | 8 |

| Cystotomy | 63 | Bucket, plastic | 94 | 6 | 0 |

| Hernia repair | 69 | Capped bottle, alcohol solution | 79 | 13 | 8 |

| Hydrocele | 88 | Disposable needles # 25, 21, 19 | 98 | 2 | 0 |

| Incision and drainage | 98 | Drum for sterile dressings | 83 | 8 | 8 |

| Laparotomy | 75 | Examination table | 90 | 10 | 0 |

| Male circumcision | 98 | Eye protection | 40 | 15 | 46 |

| Neonatal surgery | 35 | Face masks | 69 | 25 | 6 |

| Suturing | 100 | Forceps, Kocher | 73 | 19 | 8 |

| Tubal ligation/vasectomy | 71 | Forceps, artery | 81 | 10 | 8 |

| Urethral stricture | 46 | Gloves (non-sterile) | 92 | 8 | 0 |

| Gloves (sterile) | 90 | 10 | 0 | ||

| Kidney dishes, stainless steel | 88 | 13 | 0 | ||

| Light source (lamp and flashlight) | 73 | 17 | 10 | ||

| Nail brush, scrubbing | 85 | 10 | 5 | ||

| Nasogastric tubes 10 to 16 FG | 71 | 17 | 13 | ||

| Needle holder | 90 | 10 | 0 | ||

| Needles, cutting and round | 94 | 6 | 0 | ||

| Retractors | 77 | 17 | 6 | ||

| Scalpel handle with blade | 94 | 4 | 2 | ||

| Scissors blunt 14 cm | 83 | 15 | 2 | ||

| Scissors straight 12 cm | 77 | 21 | 2 | ||

| Sharps disposal container | 98 | 2 | 0 | ||

| Sheeting, plastic for exam table | 65 | 23 | 13 | ||

| Soap | 98 | 2 | 0 | ||

| Sterile gauze dressing | 96 | 4 | 0 | ||

| Steriliser | 85 | 13 | 2 | ||

| Suction pump (manual or electric) | 96 | 4 | 0 | ||

| Suture, synthetic absorbable | 90 | 10 | 0 | ||

| Syringes 10 ml | 100 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Syringes 2 ml | 100 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Thermometer | 96 | 4 | 0 | ||

| Towel cloth | 85 | 13 | 2 | ||

| Urinary catheter disposable #12, 14, 18 | 58 | 33 | 8 | ||

| Wash basin | 94 | 4 | 2 | ||

| Waste disposal container | 98 | 2 | 0 | ||

| Anaesthesiology/airway management | |||||

| Anaesthesia guidelines | 27 | 4 | 69 | ||

| Personnel | Anaesthesia machine | 67 | 0 | 33 | |

| General practitioners performing anaesthesia | 16 | Blood pressure measuring equipment | 98 | 2 | 0 |

| Non-physicians performing anaesthesia | 176 | Cricothyroidotomy set | 27 | 21 | 52 |

| Physicians trained in anaesthesiology (specialist) | 11 | Endotracheal tubes, cuffed sizes 5.5 to 9 | 65 | 8 | 27 |

| Endotracheal tubes, uncuffed sizes 3.0 to 5.0 | 54 | 19 | 27 | ||

| Procedure | P | IV cannula sizes 18, 22, 24 | 92 | 8 | 0 |

| Airway foreign body | 83 | IV infusion set | 90 | 10 | 0 |

| Cricothyroidotomy | 44 | IV Infusor bags | 73 | 10 | 17 |

| General anaesthesia | 65 | Laryngoscope handle | 71 | 15 | 15 |

| Ketamine IV | 67 | Laryngoscope Macintosh blades (adult) | 73 | 15 | 13 |

| Regional anaesthesia | 42 | Laryngoscope Macintosh blades (paediatric) | 46 | 21 | 33 |

| Resuscitation | 88 | Magills forceps (adult) | 56 | 27 | 17 |

| Spinal anaesthesia | 77 | Magills forceps (paediatric) | 38 | 23 | 40 |

| Mask and tubing to connect to oxygen supply | 46 | 27 | 27 | ||

| Oropharyngeal airway (adult) | 42 | 35 | 23 | ||

| Oropharyngeal airway (paediatric) | 21 | 23 | 56 | ||

| Oxygen concentrator | 75 | 13 | 13 | ||

| Oxygen cylinder | 33 | 31 | 35 | ||

| Pain management guidelines | 25 | 13 | 63 | ||

| Post-operative recovery room | 29 | 10 | 60 | ||

| Pulse oximetry | 13 | 4 | 83 | ||

| Resuscitator bag valve and mask (adult) | 67 | 15 | 19 | ||

| Resuscitator bag valve and mask (paediatric) | 38 | 17 | 46 | ||

| Scalp vein infusion set | 98 | 2 | 0 | ||

| Spare bulbs and batteries for laryngoscope | 44 | 27 | 29 | ||

| Stethoscope | 98 | 2 | 0 | ||

| Suction catheter sizes 16 Fr | 77 | 15 | 8 | ||

| Tongue depressor, wooden, disposable | 83 | 13 | 4 | ||

| Orthopaedics and traumatology | |||||

| Radiography | 33 | 44 | 23 | ||

| Procedure | P | Chest tube insertion equipment | 54 | 25 | 21 |

| Chest tube placement | 63 | Splints for arm, leg | 63 | 21 | 17 |

| Clubfoot repair | 35 | Tourniquet | 96 | 4 | 0 |

| Contracture release | 33 | ||||

| Debridement | 92 | ||||

| Fracture management, closed | 88 | ||||

| Fracture management, open | 61 | ||||

| Joint dislocation reduction | 92 | ||||

| Limb amputation | 65 | ||||

| Osteomyelitis/septic arthritis | 63 | ||||

| Obstetrics/gynaecology | |||||

| Vaginal speculum | 90 | 10 | 27 | ||

| Personnel | |||||

| Physicians trained in OBGYN (specialists) | 74 | ||||

| Procedure | P | ||||

| Caesarean delivery | 67 | ||||

| Dilation and curettage | 77 | ||||

| Obstetric fistula repair | 21 | ||||

C, % of facilities with consistent access; I, % of facilities with intermittent access; N, % of facilities with no access; P, % of facilities which offer the procedure.

By local convention, a physician who has trained in general surgery is considered a surgical specialist. Further specialisation, such as urologic, orthopaedic or cardiothoracic surgery, is termed as super specialty. Facilities were asked the size of the ‘population served’, intending to quantify the population living in the catchment area. This value thus represents the number of residents who would use the facility as their first-referral health facility, not the number of patients seen.

Results

Forty-eight facilities, representing 16 of 26 regions and serving 18.6 million residents (46% of the population), completed the WHO Integrated Management for Emergency and Essential Surgical Care (IMEESC) Situational Analysis research tool. The average population served per facility was 425 000, though five facilities served 10 000 or fewer residents. A total of 9085 hospital beds were reported, averaging 189 beds per facility (range 15–350 beds). One hundred eighteen operating rooms were identified.

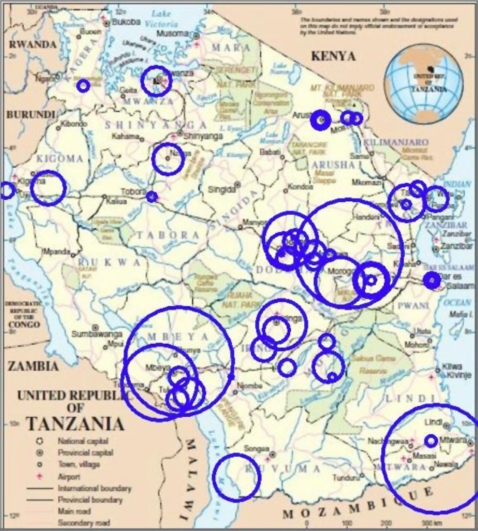

The weighted mean of distance travelled prior to admission was 119 km (74 miles). Figure 1 displays the locations of facilities with markers sized to the population served. This map demonstrates that the six facilities serving the largest population are located on the southern and northern periphery. The central regions are dominated by health facilities in rural areas serving small populations.

Figure 1.

Facilities evaluated. Ring size proportional to population served.

Annual admissions averaged 2001 per facility (range 350–5000). On average, 34% of all admissions required either minor or major surgical interventions.

A total of 4965 healthcare providers were reported in the 48 facilities. Sixty-four surgical specialists (ie, physicians with dedicated surgical training) were identified, and 56 (88%) of identified surgical specialists were employed by the six largest hospitals. The great majority of anaesthesia providers (176/203=87%) were non-physicians, and only 11 formally trained anaesthesiologists were identified. Other medical staff providing surgical and anaesthesia services in the facilities included 4017 assistant medical officers (non-physician medical officers, paramedics and midwives).

Of the 35 basic interventions listed in the tool, only suturing was available at all facilities. Additionally, incision and drainage, male circumcision and wound debridement were widely available and provided at 98%, 98% and 92% of facilities, respectively. Caesarean section was available at 67% of facilities.

Equipment was largely inadequate, including a significant gap in availability of functioning anaesthesia machines. Running water and electricity were widely available with only two facilities having no access to either water or electricity. However, only 37.5% of facilities reported both consistent running water and electricity. Greater than half of facilities reported never using eye protection and 46% reported no access to this critical piece of personal protective equipment. Six facilities had all essential equipment consistently available: Bombo Regional Hospital, Dodoma Regional Hospital, St Francis District Hospital, Ilembula Hospital, Besha Health Centre and Muhimbili National Hospital. Oxygen supplies were inconsistent in many facilities. Twenty facilities (42%) had uninterrupted access to oxygen, with most relying on oxygen concentrators. Fifteen facilities (32%) had no access to an anaesthesia machine of any kind. Of all facilities surveyed, only six pulse oximeters were located. In Tanzania, the regional blood bank system is independent of any hospital facility and 77% of facilities reported having a blood bank. The x-ray was fully functional in 33% of facilities and interrupted in 44%, leaving 23% of facilities with no radiographic capacity. All facilities have access to haemoglobin and urine analysis testing.

Complete results from the evaluation are shown in table 1. Information was placed into one of four mutually exclusive and comprehensive medical fields. For simplification, in table 1, laboratory tests and other infrastructure (ie, blood bank, electricity) were included under equipment.

Discussion

More than 5 million people die from injuries every year and many more are left with permanent disabilities. Significant disparities in care exist between high- and low-income countries for patients with surgically treatable conditions. An estimate of the global burden of surgery showed that only 26% of estimated surgical procedures were performed in low-income countries, despite these countries accounting for 70% of the global population.2 Of the estimated 536 000 maternal deaths in 2005, developing countries accounted for 99% of these deaths6; much of this mortality could be prevented by timely access to emergency and basic surgical services.

The provision of surgical services has historically been neglected in public health programmes.7 It is often assumed that surgery and anaesthesia interventions are expensive, technologically demanding and can only be delivered in large hospitals and by specialists. However, limiting surgical care to large facilities in developing countries makes it inaccessible to the large segment of the population in decentralised areas. Experience shows that basic surgical services can be cost-effective and safely delivered even in settings with limited resources.8

Two studies have examined the cost-effectiveness of small hospitals performing basic surgical operations in resource poor settings.9 10 The cost per DALY averted in each study for all patients seen was US$10.93 and US$32.78. Although these studies did not separate surgical from non-surgical patients in calculating cost/DALY, both hospitals had a significant percentage (29%–67%) of surgical diagnoses contributing to the calculation. These costs compare favourably with other primary health interventions in developing countries.1

WHO developed the IMEESC toolkit that has been implemented in 37 countries including Tanzania in January 2007.5 Targeted activities to improve surgical capacity have included the formation of a formal ‘Surgical Task force’ in Tanzania MoHSW, training courses, the adoption of IMEESC toolkit by the Tanzania Surgical Association and hosting the biennial WHO GIEESC meeting in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

WHO GIEESC was established in 2005 as a collaboration of local and international organisations, academia, health authorities and WHO, in response to the recognition of surgery as a critical component of population based health.5 The research arm of WHO GIEESC developed WHO situational analysis tool to provide data in surgical care capacity to assist ministries of health in low- and middle-income countries for making evidence-based improvements.

This study provides an overview of the capacity for surgical care in 16 regions of Tanzania and demonstrates the significant gaps in infrastructure, human resources, life-saving and disability-preventive surgical interventions and essential equipment.

Despite the introduction of WHO programme for emergency and essential surgical care in Tanzania in 2007 and the efforts by the Tanzanian MoHSW to train non-physicians to deliver select surgical services such as caesarean sections, skilled health personnel to deliver surgical services remain inadequate for a significant portion of the country. This deficit is most pronounced in the rural areas, where patients travel great distances to reach health facilities and consequently face significant delays in care.

Although most facilities had a functioning operating theatre, fewer than half had uninterrupted access to oxygen and a third of facilities did not have access to an anaesthesia machine as is seen in many sub-Saharan African countries.11 Significant improvements in surgical mortality in developed countries have resulted from improvements in the delivery of safe anaesthesia. The existing gap of safe anaesthesia services likely limits the availability of life-saving surgeries in Tanzania or results in significant complications and unnecessary patient suffering when anaesthesia is not available.

Of the 35 basic surgical interventions, many hospitals did not have the capacity to deliver all the basic services. As demonstrated in figure 2, this survey showed that facilities in the central and southern region had less capacity to provide basic surgical services. Additionally, the consistent lack of oxygen tubing, pulse oximeters and paediatric airway equipment is a significant barrier to the provision of life-saving services in the regions studied.

Figure 2.

Rings sized on ratio of (population served: annual procedures). Large rings are underserved.

Delivery of surgical services is dependent on the availability of all components inherent in a functioning health system. Systematic changes that address human resources, supplies/equipment and infrastructure are necessary to improve mortality from surgically treatable conditions. The benefits of these changes will significantly impact the mortality of patients with obstetric-related emergencies and traumatic injuries, particularly women and children. However, the efforts made to improve disease-specific surgical interventions will not have an isolated impact on surgically treatable conditions and meet the Millennium Development Goals 4, 5 and 6. Systematic changes such as investments in oxygen and related equipment and appropriately trained surgical workforce will also serve to benefit patients suffering from a range of conditions including sepsis, pneumonia, HIV-related conditions and other infectious diseases.

There are several limitations to this survey. First, it provides only a brief overview of the capacity for surgical care and cannot be used for detailed programme planning. Second, an independent observer did not verify the answers provided in the survey by the health provider or director of the health facilities. Third, it does not capture data from every first-referral health facilities of the country.

This survey presents the first snapshot of life-saving surgical services in Tanzania using WHO Tool for Situational Analysis to Assess Emergency and Essential Surgical Care. This snapshot view provides additional evidence that investments in human resources, essential equipment and infrastructure are needed to strengthen district surgical services in Tanzania to benefit rural population. Addressing the unmet need of surgical (including anaesthesia, obstetrics and trauma) services within existing related national programmes for maternal and child health will strengthen health systems, particularly at the district level.12 These investments will have the secondary effect of improving the overall healthcare system and the treatment of many non-surgical conditions. Further research is needed to quantify the true burden of surgical disease in Tanzania and the cost–benefit of specific interventions to improve surgical services.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The following members of GIEESC in Tanzania were instrumental in obtaining the reported data: Professor Neboth Mbembati, Professor Victor Mwafongo, Dr Paul Mareale, Dr Jasper Mbwambo, Dr Amani Malima, Dr Mtumwa Ibrahim and Dr Rashid Mayoka.

Footnotes

To cite: Penoyar T, Cohen H, Kibatala P, et al. Emergency and surgery services of primary hospitals in the United Republic of Tanzania. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000369. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000369

Contributors: TP analysed and interpreted the data, drafted the article, revised it and finally approved the submitted version. HC contributed to conception and design, acquisition and interpretation of data, made critical revisions and finally approved the submitted version. PK contributed to acquisition of data, made critical revisions and finally approved the submitted version. AM contributed to acquisition of data, made critical revisions and finally approved the submitted version. GS contributed to acquisition of data, made critical revisions and finally approved the submitted version. LN contributed to conception and design, interpretation of data, made critical revisions and finally approved the submitted version. SG contributed to conception and design, interpretation of data, made critical revisions and finally approved the submitted version. DHM contributed to acquisition of data, made critical revisions and finally approved the submitted version. MC contributed to conception and design, acquisition and interpretation of data, helped draft the article, made critical revisions and finally approved the submitted version.

Funding: None.

Disclaimer: The authors include staff members of WHO. They are responsible for the views expressed in this publication and do not necessarily represent the decisions or stated policy of WHO.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available, all has been included.

References

- 1.Debas HT, Gosselin R, McCord C, et al. Surgery. In: Jamison D, ed. Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries. 2nd edn New York: Oxford University Press, 2006:1245–59 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weiser TG, Regenbogen SE, Thompson KD, et al. An estimation of the global volume of surgery: a modeling strategy based on available data. Lancet 2008;372:139–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization (Internet site) Geneva: World Health Organization; http://www.who.int/countries/tza/en/ (accessed 18 Feb 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mwakyusa D. The National Road Map Strategic Plan to Accelerate Reduction of Maternal, Newborn and child deaths in Tanzania 2008–2015. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: Annual Summit of MoHSW, 2008:1–13 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Emergency and essential surgical care (Internet site). Geneva: World Health Organization; http://www.who.int/surgery (accessed 18 Feb 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maternal mortality in 2005: estimates developed by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA and the World Bank. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2007. http://www.who.int/reproductive-health/publications/maternal_mortality_2005/mme_2005.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cherian M, Choo S, Wilson I, et al. Building and retaining the neglected anaesthesia health workforce: is it crucial for health systems strengthening through primary health care? Bull WHO 2010;88:637–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laxminarayan R, Mills AJ, Breman JG, et al. Advancement of global health: key messages from the Disease Control Priorities Project. Lancet 2006;367:1193–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gosselin R, Thind A, Bellardinelli A. Cost/DALY averted in a small hospital in Sierra Leone: what is the Relative Contribution of Different services? World J Surg 2006;30:505–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCord C, Chowdhury J. A cost-effective small hospital in Bangladesh: what it can mean for emergency obstetric care. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2003;81:83–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Belle J, Cohen H, Shindo N, et al. Influenza preparedness in low-resource settings: a look at oxygen delivery in 12 African countries. J Inf Dev Count 2010;4:419–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hedges JP, Mock CN, Cherian MN. The Political Economy of emergency and essential surgery in global health. World J Surg 2010;34:2003–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.