Abstract

The present study tests a developmental model designed to explain the romantic relationship difficulties and reluctance to marry often reported for African Americans. Using longitudinal data from a sample of approximately 400 African American young adults, we examine the manner in which race-related adverse experiences during late childhood and early adolescence give rise to the cynical view of romantic partners and marriage held by many young African Americans. Our results indicate that adverse circumstances disproportionately suffered by African American youth (viz., harsh parenting, family instability, discrimination, criminal victimization, and financial hardship) promote distrustful relational schemas that lead to troubled dating relationships, and that these negative relationship experiences, in turn, encourage a less positive view of marriage.

Keywords: African American, Dating, Discrimination, Marriage, Relational schemas, Romantic relationships

In the past three decades much research has focused upon the sharp racial disparities that have come to exist regarding romantic relationships and union formation. This body of work has produced substantial support for two empirical generalizations that inform the present study. First, numerous studies have documented that Black Americans are much less likely to marry than Whites (Goldstein & Kinney, 2001; Clayton, Miney, & Blankenhorn, 2003). African Americans are more apt to cohabitate than Whites, but these relationships are less likely to lead to marriage than is the case for Whites. Second, there is strong evidence that the romantic relationships of African Americans are more troubled than those of European Americans. Research by Anderson (1990, 1999) and Wilson (2003), for example, indicated that the romantic relationships of African American teens and young adults are often fractious, antagonistic, and unstable, and Kurdek (2008) recently reported that Black dating couples exhibited more arguing and relationship dissatisfaction than White couples. Further, Blacks who marry tend to report lower marital quality (Oggins, Veroff, & Leber, 1993) and higher rates of intimate partner violence (Hampton, Gelles, & Harrop, 1989; Rennison & Welchans, 2000) and divorce (Fields & Casper, 2001; Sweeney & Phillips, 2004) than Whites.

The most popular explanations for these racial/ethnic differences emphasize marriage market conditions (Oppenheimer, 1988; Wilson, 1987) and economic hardship (Edin, 2000; Wilson, 1987, 1996). Although these structural factors explain a portion of the gap, differences persist that cannot be explained (Bennett, Bloom, & Craig, 1989; Lichter, McLaughlin, Kephart, & Landry 1992; Crissey, 2005). Further, some have noted that racial/ethnic variation regarding the meaning and importance of marriage contributes to differences in family formation (Cherlin, 1992; Crissey, 2005; Sassler & Schoen, 1999) and this variation in beliefs and expectations about marriage tend to emerge during adolescence, well before individuals are making decisions about whether to marry (Crissey, 2005). This suggests that differences in attitudes about marriage are not entirely explained by structural conditions such as the marriage market or economic hardship.

Much of the current research on adolescent dating employs a developmental framework that emphasizes the way that teen dating relationships serve as developmental precursors, as a sort of training ground, for adult romantic involvements (Conger, Ming, & Bryant, 2001; Smock, Manning, & Porter, 2004; Raley, Crissey, & Muller, 2007). Early romantic experiences are seen as shaping an individual’s view and approach to adult relationships, including marriage (Brown, Feiring, & Furman, 1999; Crissey, 2005). This perspective suggests that there is likely to be a link between the higher rates of troubled romantic relationships seen among African American adolescents and young adults and their subsequent reluctance to marry. Dating relationships characterized by chronic discord, frustration, and disappointment are likely to foster a more negative view of the costs and benefits of marriage.

This suggests that understanding the causes of ambivalence toward marriage evident among many African Americans requires identification of the factors that give rise to the conflict and antagonism that often characterizes their romantic relationships. In the present study, we develop and test the proposition that child and adolescent exposure to race-related disadvantages and stressful events such as discrimination, economic hardship, community crime, and harsh parenting give rise to cynical, distrusting relational schemas and that these schemas increase the probability of discordant romantic relationships during late adolescent and early adulthood. Further, we test the idea that that troubled romantic relationships, in turn, foster less positive views of marriage. These hypotheses are examined using structural equation modeling and longitudinal data from a sample of 377 African Americans.

RELATIONAL SCHEMAS AND ROMANTIC RELATIONSHIPS

Numerous studies over the past two decades have shown that relational schemas serve as a link between people’s past experiences and their approach to subsequent social relationships (Dodge & Pettit, 2003). Schemas are simplifying suppositions that make defining and responding to situations more efficient as they suggest which cues are most important, the meaning of these stimuli, and the likely consequence of various courses of action (Baldwin, 1992; Crick & Dodge, 1994). Relational schemas consist of assumptions regarding the nature of the self, other people and social relationships (Baldwin, 1992; Dodge & Pettit, 2003). Hundreds of studies have investigated child and adolescent experiences that give rise to variations in such schemas as well as the consequences that such variations portends for ensuing relationships, especially those involving romantic partners (Fenney, 1999; Orobio de Castro et al., 2002). Much of this research has focused upon cynical, distrusting schemas involving either insecure attachment or hostile attribution bias. Both of these relational schemas are considered in the present study. We develop hypotheses suggesting that adverse race-related events give rise to these negative schemas and that these schemas, in turn, foster troubled relationships with romantic partners and a diminished view of marriage. The remainder of this section presents the rationale for these hypotheses.

Attachment theory asserts that children develop an attachment style based on the nature of the relationship with their primary caregivers (Bowlby, 1969, 1982). Attachment styles represent working models of relationships or relational schemas that are induced from the behavior of caregivers and generalized to interaction with others (Bowlby, 1973, 1982). A loving, supportive caretaker promotes secure attachment and a trusting, optimistic view of people and relationships, whereas a rejecting or a neglecting caregiver fosters insecure attachment and a distrusting, cynical view of people and relationships. This theory is uniquely suited to the study of romantic relationships as it posits that the attachment style that an individual develops during childhood influences subsequent interaction with intimate partners (Bretherton & Munholland, 1999; Crowell, Fraley, & Shaver, 1999).

There is strong evidence that individuals who hold insecure relational schemas interpret and respond to romantic partner behavior differently than securely attached persons. Studies have reported, for example, that insecurely attached individuals are more likely than securely attached persons to perceive partners as insensitive and untrustworthy (Collins, 1996), attribute malevalent intentions (Collins, Ford, Guichard, and Allard, 2006; Gallo & Smith, 2001; Pearce & Halford, 2008), engage in dominating or coercive actions (Feeney, Noller, & Callan, 1994; Levy & Davis, 1988; Simons, Simons, & Burt, 2008), and exhibit threatening and hostile behavior (Simpson, Rhodes, & Phillips, 1996). As a consequence, the romantic relationships of insecurely attached persons involve more conflict and less intimacy and satisfaction, including sexual satisfaction (Butzer & Campbell, 2008), than the relationships of securely attached individuals (see Feeney, 2008; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007).

Over the past 3 decades, Ken Dodge and his colleagues (1980; 1986; Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, 1990) have investigated the causes and consequences of a hostile attribution bias. Like insecure attachment, this relational schema involves a cynical, distrustful view of others. Individuals with a hostile attribution bias tend to assume that other people have malevolent motives and that an intimidating, confrontational style of interaction is necessary to avoid exploitation. Research has shown that this view of relationships is strongly held by aggressive children and adolescents (Lansford et al., 2002; Dodge & Newman, 1981; Zelli, Dodge, Lochman, & Laird, 1999). Indeed, a meta-analysis of over 100 studies reported a robust association between hostile attributions and youth aggression (Orobio de Castro et al., 2002). Further, there is evidence that aggressive adults (Epps & Kendall, 1995; Bailey & Ostrov, 2007; Vitale, Newman, Sterin, & Bolt, 2005) demonstrate a hostile attribution bias. Finally, as with insecure attachment, studies have found that children and adolescents learn this relational schema when their parents are harsh and rejecting (Dodge et al., 1995; MacKinnon-Lewis, Lamb, Hattie, & Baradaran, 2001; Runions & Keating, 2007) and that it increases the probability of behaving aggressively with romantic partners (Fite, Bates, Holtzworth-Munroe, Dodge, Nay, & Pettit, 2008; Holzworth-Munroe, 2000; Jin, Eagle, & Keat, 2008).

Importantly, research indicates that the distribution of individuals possessing distrustful relational schemas varies by race/ethnicity. Using a large nationally representative sample, Mickelson, Kessler, and Shaver (1997) found that African Americans were 20% more likely to possess an insecure attachment style than European Americans. Similar differences were reported in a study that used the NICHD Early Childcare Research Network data set (Bakermans-Dranenburg, van Ijzendoorn, & Kroonenberg, 2004). And, the findings of Pinderhughes, Dodge, Bates, Pettit, and Zelli (2000) indicated that Black adolescents are more likely than White adolescents to demonstrate a hostile attribution bias.

Why would African Americans have disproportionately high rates of insecure attachment and hostile attribution bias? We expect that there are two answers to this question. First, as noted above, both Bowlby and Dodge argued that negative relational schemas are induced, in large measure, from childhood family experiences. As noted earlier, past research has established that the divorce rate for African Americans is nearly double that of Whites (Fields & Casper, 2001; Sweeney & Phillips, 2004). Further, past research has also reported that African American children are more likely to experience harsh discipline, often including corporal punishment, than White Children (McLoyd, Cauce, Takeuchi, & Wilson, 2000). This higher rate of harsh parenting by African Americans is usually seen as emotional spillover from the frustrations of poverty and racism (McLoyd et al., 2000; White & Rogers, 2000). In addition, African Americans residing in impoverished neighborhoods sometimes use severe punishment to ensure that their children avoid dangerous situations (Burton & Jarrett, 2000). Regardless of the causes, however, it appears that African American children are more likely than other ethnic groups to experience family instability and harsh parenting. These family experiences have been linked to insecure attachment and hostile attribution bias and probably contribute to the higher proportion of African Americans with insecure attachment and hostile attribution bias.

Second, both Bowlby (1982) and Dodge (Dodge & Pettit, 2003) have contended that negative relational schemas are tempered or amplified by extra-familial experiences that provide information about the nature of people and relationships. Building upon this idea, we posit that the hardships and stressful events disproportionately suffered by African Americans in the course of growing up contribute to their development of negative relational schemas. Black children and adolescents are much more likely than White youth to encounter racial discrimination, neighborhood crime, and family financial hardship. Such experiences might be expected to foster a cynical, distrustful perception of people and relationships. The common lesson running through these events is that people are often exploitive and uncaring and one must be hyper-vigilant in order to avoid being mistreated. Consistent with this contention, Mickelson et al. (1997) found that family financial adversity and criminal victimization (e.g., assault, rape, threatened with weapon) were associated with insecure attachment. And, recent studies have linked both racial discrimination (Simons et al. 2002, 2006) and living in a high crime neighborhood (Simons & Burt, 2011) to development of a cynical, hostile view of people and relationships. Thus, in addition to family instability and harsh parenting, it seems likely that race-related strains and stressors involving economic hardship, exposure to criminal behavior, and racial discrimination increase the chances that African American youth will develop an insecure attachment style and hostile attribution bias.

MODEL TO BE TESTED

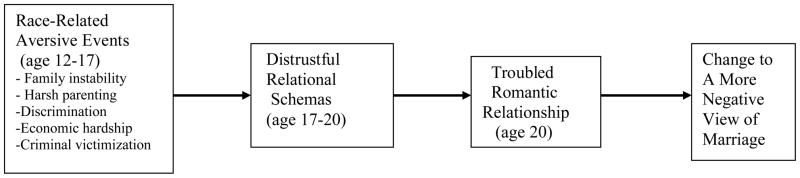

The sequence of findings presented in the previous section suggests a causal model of the process whereby African Americans develop a negative view of marriage. This model is presented in Figure 1. The model posits that persistent exposure during late childhood and adolescence to race-related aversive events involving harsh parenting, family instability, financial hardship, criminal victimization, and discrimination foster a distrusting view of people and relationships (i.e., distrusting relational schemas). Based upon findings reported above, persons committed to such an interpersonal perspective are likely to perceive romantic partners as inconsiderate and untrustworthy, attribute malevolent motives, and engage in controlling or coercive actions. Thus our model predicts that distrusting relationship schemas will lead to troubled romantic relationships.

Figure 1.

Theoretical Model to be Tested.

Past research suggests that romantic relationships in late adolescence and emerging adulthood operate as a training ground for later adult romantic involvements (Brown et al., 1999; Conger et al., 2001; Raley et al, 2003). Thus it is likely that dating relationships characterized by chronic discord, frustration, and disappointment color the parties’ perceptions of what marriage has to offer. Consonant with this view, our model depicts an association between being in a troubled romantic relationship and adoption of a more negative view of the likely costs and benefits of marriage.

Regardless of the nature of their relational schemas, most individuals eventually become involved in a romantic relationship. Prior to such relationship experiences, we assume that individuals tend to possess relatively ill defined notions of marriage. It is involvement with a romantic partner that shapes and sharpens a person’s beliefs about what marriage is likely to entail. Thus relational schemas do not directly influence an individual’s view of marriage; rather, they exert an indirect influence on views of marriage through their impact on the quality of romantic relationships when they occur.

METHOD

Data

We tested our hypotheses using data from waves 2 – 5 of the Family and Community Health Study (FACHS), a multi-site investigation of neighborhood and family effects on health and development (Conger et al., 2001; Gibbons et al., 2004; Simons et al., 2002). The FACHS sample consists of 867 African American families living in Georgia and Iowa at the initiation of the study. Each family included a child who was in 5th grade at the time of recruitment (See Simons et al. 2006).

Families were recruited from neighborhoods that varied on demographic characteristics, specifically racial composition (percent African American) and economic level (percent of families with children living below the poverty line). Block groups (BGs) were used to identify neighborhoods. Using 1990 census data, BGs were identified in both Iowa and Georgia in which the percent of African American families was high enough to make recruitment economically practical (10% or higher), and in which the percent of families with children living below the poverty line ranged from 10% to 100%. Using these criteria, 259 BGs were identified (115 in Georgia and 144 in Iowa). In both Georgia and Iowa, families were randomly selected from these rosters and contacted to determine their interest in participating in the project. The response rate for the contacted families was 84%.

To evaluate the variability and representativeness of the neighborhoods included in our sample, we compared census tracts included in the FACHS sample with those in Georgia and Iowa that were not included. No significant differences were found in Iowa. For Georgia, average and median family incomes were somewhat lower among the tracts in the study than in those excluded. Further analysis showed this to be a result of the study sample having a slight under-representation of high-income census tracts.

Twenty-eight percent of the children lived with both biological parents, 38% with a cohabitating or married stepparent, and 35% with a single parent. Most (84%) of the primary caregivers were the target child’s biological mother (6% were the child’s father, 6% were the child’s grandmother). Their mean age was 37.1 years and ranged from 23 to 80 years. Education ranged from less than high school (19%) to advanced graduate degrees (3%). The mode and median was a high school degree (41%). Ninety-two percent of the primary caregivers identified themselves as African American. Seventy-one percent were employed full or part-time, 15% were unemployed, 6% were disabled, and 5% were full-time homemakers. Median family income was $26,227 and average number of children was 3.42. There was no significant difference in income or education of the primary caregiver between the Iowa and Georgia subsamples.

The respondents were approximately 12.5 years of age at wave 2, 14.5 years of age at wave 3 and 17 years of age at wave 4, and 20 years of age at wave 5. The retention rate was quite high across the five waves of data collection. At wave 5, 689 individuals, or 80% of the original sample, were re-interviewed. Originally, all of the respondents resided in Georgia or Iowa, but by wave 5 they were scattered among 23 states. Over the years, there has been little evidence of selective attrition. For example, analyses indicated that non-participants at wave 5 did not differ significantly from participants at wave 1 with regard to family income, parents’ education, the target child’s school performance, or depression.

Most of the analyses presented in this paper focus upon the 55% of respondents who reported at wave 5 that they were involved in a romantic relationship. These were individuals who checked one of the following categories: I see one person on a regular basis; I am in a committed relationship but not engaged; I am engaged to be married (but don’t live together); I live with my romantic partner but we have no plans to marry; I live with my romantic partner and we are engaged to marry. This consisted of 159 men and 221 women.

The remaining 45% of the sample (i.e., those classified as not having a romantic partner) checked one of the following two categories: I am not dating or seeing anyone right now; I date but do not have a romantic relationship with anyone. Analysis indicated that those with a romantic partner did not differ from those without a romantic partner in terms of antisocial behavior, education, or family SES. Importantly, they also did not differ regarding relational schemas or exposure to any of the independent variables (discrimination, family instability, etc.) in the theoretical model to be tested.

Procedures

A similar set of procedures were employed at each wave. Before data collection began, focus groups in Georgia and Iowa examined and critiqued the self-report instruments. Each group was composed of 10 African American women who lived in neighborhoods similar to those from which the study participants were recruited. The focus groups and pilot tests did not indicate a need for changes in any of the instruments used in the present paper.

To enhance rapport and cultural understanding, African American university students and community members served as field researchers to collect data from the families in their homes. Prior to data collection, the researchers received a week of training in the administration of the self-report instruments. Each interview was conducted privately, with no other family members present. The instruments were presented on laptop computers. Questions appeared in sequence on the screen, which both the researcher and participant could see. The researcher read each question aloud and the participant entered a response using the computer keypad.

Measures

Harsh parenting

At waves 2–4, respondents’ answered 14 questions regarding how often during the preceding year that the primary caregiver engaged in various harsh parenting practices when they became upset (e.g., How often did your mother push, grab, hit or shove you? How often does your mother insult or swear at you?). This scale has been used in numerous papers and has strong reliability and validity (see Simons et al., 2006, 2007). Coefficient alpha was .73 at wave 2, .77 at wave 3, and .78 at wave 4. Scores were standardized and then summed across waves to form a composite measure of persistent exposure to harsh parenting.

Discrimination

At waves 2–4, the target youths completed 13 items from the Schedule of Racist Events (Landrine & Klonoff, 1996). This instrument has strong psychometric properties and has been used extensively in studies of African Americans. The items assess the frequency (1=never, 4=several times) with which various discriminatory events (e.g., racial slurs, hassled by police) were experienced during the preceding year. Coefficient alpha for this scale was .81 at wave 2, .82 at wave 3, and .85 at wave 4. Scores were standardized and then summed across waves to form a composite measure of persistent exposure to discrimination.

Community crime

The measure of neighborhood crime was assessed with a revised version of the community deviance scale developed for the Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods (PHDCN; Sampson et al., 1997). The 9-item measure is concerned with how often various criminal acts occur within the respondent’s community. It includes behaviors such as fighting with weapons, robbery, gang violence, and sexual assault. Coefficient alpha was .68 at wave 2, .74 at wave 3, and .73 at wave 4. Scores were standardized and then summed across waves to form a composite measure of persistent exposure to neighborhood violence.

Family Financial Hardship

At waves 2–4, the adolescents’ primary caregiver reported the extent to which they had experienced 13 different financial stressors (e.g., lost job, couldn’t pay bills). These items, plus family income, were standardized and summed across waves to form a measure of persistent exposure to family financial hardship.

Cummulative Family Instability

Family structure at wave 2 was coded as married – biological parent, married - stepparent, cohabitating, single parent, or other. Following Cavanagh et al., (2008), cumulative family instability was assessed by summing whether family structure had changed at each wave.

Distrustful View of Relationships

This construct was treated as a latent construct with two indicators: a measure of insecure attachment and a measure of hostile attribution bias. Past research indicates that these two schemas are related. For example, insecurely attached individuals tend to display a hostile attribution bias in interaction with peers (Thompson, 2008) and romantic partners (Collins et al., 2006). Both of these relational schemas are assumed to be relatively stable by early adulthood. Thus at waves 4 and 5, we assessed insecure attachment using the Experiences in Close Relationships-Revised (ECR-R; Fraley, Waller, & Brennan, 2000) which improves the measurement precision and construct validity of the original ECR scale (Brennan, Clark, & Shaver, 1998). The instrument asks respondents to report the extent to which they agree (1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree) with items such as: I often worry that my partner doesn’t love me, I am nervous whenever anyone gets too close to me, and I find it difficult to trust others. The ECR scale has been used in numerous studies and has excellent reliability and validity (Feeney, 2008). Coefficient alpha was .79 at wave 4 and .76 at wave 5. Scores for the two waves were summed to form a composite measure of insecure attachment. The correlation between waves was .40 and internal consistency for the composite measure was .82.1

Hostile attribution bias was also assessed at waves 4 and 5. A 5-item measure developed for the FACHS project (Simons et al., 2006) was used as a measure of this construct. The items focus on the extent to which respondents believe that people are untrustworthy and exploitive (e.g., People often try to take advantage of you) and that aggressive actions are therefore necessary and legitimate in order to defend oneself (e.g., Sometimes you need to threaten people in order to get them to treat you fairly). Response format for these items ranged from (1) strongly disagree to (5) strongly agree. Coefficient alpha for this instrument was roughly .60 at wave 4 and .64 at wave 5. Scores for the two waves were summed to form a composite measure of hostile attribution bias. The correlation between waves was .42 and internal consistency for the composite measure was .72.

Troubled romantic relationship

Two scales were treated as indicators of the latent construct Troubled Romantic Relationship. The first was the relationship hostility scale, a 5-item measure of the respondents’ self-reports of their hostile behavior (e.g., criticize, shout, argue, hit) toward their partner during the previous month (Cui, Lorenz, Conger, Melby & Bryant, 2005; Donnellan, Assad, Robins, & Conger, 2007). Coefficient alpha for this scale was .71. The second measure asked the respondents to answer the same questions regarding their partner’s hostile behavior toward them (e.g., how often did your partner get angry at you?). Coefficient alpha for this scale was .73. Past research has shown that these two measures are highly correlated and show significant associations with observer ratings of couple interaction (Cui et al., 2005).

Negative view of marriage

At waves 4 and 5, respondents were asked to report how much they agreed (1=strongly agree, 5=strongly disagree) with five statements regarding marriage: Marriage leads to a fuller life, marriage leads to a happier life, life becomes harder when a person gets married (reverse coded), being married or getting married is the most important part of my life, and, a person who marries loses a lot of his or her freedom (reverse coded). Coefficient alpha for the scale was .65 at both waves.

ANALYTIC STRATEGY

To obtain assessments of persistent exposure to adversity, we summed the measures for each of the adverse events included in our model (viz., family instability, harsh parenting, discrimination, criminal victimization, and economic hardship) across Waves 2, 3 and 4 (ages 12 – 17). An alternative approach was to assess change in the adverse events across the three waves of data. The literature on relational schemas, however, describes them as durable internal representations of the patterns intrinsic to the repeated and persistent interactions to which the individual has been exposed (Bordieu, 1990Bordieu, 1998; Sallaz & Zavisca, 2007). This suggests that it is persistence or consistency that is most salient in the acquisition of a particular schema. We did try using change in the adverse events in place of the summed measure, but the summed measure showed much stronger associations with the measures of insecure attachment and hostile attribution. Thus, consistent with the arguments of schema theorists (Bowlby, 1973; Dodge, 1986; Dodge & Pettit, 2003), our data suggests that it is continuity or persistence of environmental conditions that are important in the etiology of relational schemas.

The variable distrustful view of relationships was treated as a latent construct. Composite measures (using waves 4 and 5; ages 17–21) of insecure attachment and hostile attribution bias served as indicators for this latent construct. The variable troubled romantic relationship was also treated as a latent construct. Respondent reports at wave 5 of their own and their romantic partner’s hostile and coercive actions served as indicators for this latent construct. Finally, we used wave 4 and wave 5 assessments of beliefs about marriage to assess change in this construct.

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was employed to test the hypothesized model presented in Figure 1. We used the statistical program MPlus Version 5.1 (Muthen & Muthen, 2008). Although the study variables were generally symmetric and normally distributed, we utilized maximum likelihood parameter estimates with standard errors and a mean-adjusted chi-square statistic which is robust to non-normality. To assess goodness-of-fit, Steiger’s Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA; Browne & Cudeck 1992), the comparative fit index (CFI; Bentler 1990), and the chi-square divided by its degrees of freedom (fit ratio) were used. The CFI is truncated to the range of 0 to 1 and values close to 1 indicate a very good fit (Bentler 1990). A RMSEA smaller than .05 indicates a close fit, whereas a RMSEA between .05 and .08 suggests a reasonable fit (Browne & Cudeck 1992). Originally, our models included family income and caregiver education as controls. Neither of these variables, however, was related to the endogenous constructs distrustful view of relationships, troubled romantic relationship, or negative view of marriage. Hence, in the interest of parsimony, they were deleted in the analyses presented below.

MPlus has two options for calculating the standard errors for indirect effects: the delta and bootstrapping methods. We estimated standard errors using both methods, and the results were analogous. Significance levels presented are based on the results from the default delta method.

Finally, we tested for differences between the models for men and women using the multiple group analysis option in Mplus. We began by estimating a model that constrained the paths for men and women to be equal. Next, we estimated a model that freed the paths to vary by gender. The chi-square difference between the models was significant, indicating structural non-invariance. That is, the model fit was significantly worse when the paths were constrained to be equal for men and women. To determine which paths were different, we relaxed one path in the constrained model at a time and compared it with the constrained model’s chi-square with one degree of freedom.

RESULTS

Prior to testing the study hypotheses, we ran a logistic regression to determine whether the various adverse events included in our model were related to the probability of being in a romantic relationship. The results (not shown) indicated that none of these variables were significantly related to having a romantic partner. This was true for both men and women.

Table 1 presents the correlation matrix for the study variables. The associations above the diagonal are for women whereas those below the diagonal are for men. The pattern of correlations is similar for men and women and is generally consistent with the hypothesized model. The table shows that insecure attachment and hostile attribution bias, the two measures of a distrustful view of relationship, were correlated .41 for men and .45 for women. The associations between target and partner hostility, the two indicators of troubled romantic relationship, were .65 and .74 for men and women, respectively. As expected, the various measures of persistent adversity tended to be related to insecure attachment and hostile attribution bias. And, insecure attachment and hostile attribution, in turn, were correlated with target and partner hostility. Finally, target and partner hostility were related to a negative view of marriage, although the correlations are larger for men than women.

Table 1.

Correlation Matrix for Study Variables by Gender1

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | Mean (W) | S.D. (W) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Harsh Parenting (w2 – w4) | — | .24 ** | .00 | .21 ** | .12 | .21 ** | .35 ** | .15 * | .12 † | .11 | .01 | 44.81 | 10.05 |

| 2. Community Crime (w2–w4) | .12 | — | −.03 | .27 ** | .08 | .19 ** | .27 ** | .09 | .11 | −.02 | .07 | 18.30 | 3.38 |

| 3. PC’s marital instability (w2–w4) | .03 | .07 | — | .00 | .01 | .07 | .12 † | −.12 † | −.06 | −.01 | .04 | .72 | .87 |

| 4. Discrimination (w2–w4) | .33 ** | .28 ** | .01 | — | .01 | .10 | .19 ** | −.04 | −.01 | .03 | −.03 | 32.89 | 9.06 |

| 5. Financial Hardship (w2–w4) | −.15 | .00 | .13 | .14 | — | −.05 | .02 | .07 | .00 | .04 | −.05 | 12.01 | 3.39 |

| 6. Insecure Attachment (w 4–w 5) | .29 ** | .18 * | .12 | .18 * | .22 ** | — | .45 ** | .23 ** | .24 ** | .04 | .12 † | 47.22 | 13.06 |

| 7. Hostile Attribution Bias (w4–w5) | .21 * | .30 ** | .22 ** | .33 ** | .11 | .41 ** | — | .12 † | .14 * | .11 | .14 † | 3.46 | 2.18 |

| 8. Target Hostility (w 5) | .17 * | .09 | .14 | .16 * | .06 | .15 † | .23 ** | — | .74 ** | .02 | .12 | 7.97 | 2.32 |

| 9. Partner Hostility (w 5) | .13 | .16 † | .09 | .25 ** | .22 ** | .25 ** | .31 ** | .65 ** | — | .07 | .16 * | 7.81 | 2.27 |

| 10. Negative View of Marriage (w 4) | .03 | .07 | .13 | .08 | .00 | .12 | .04 | .06 | −.02 | — | .26 ** | 14.20 | 2.49 |

| 11. Negative View of Marriage (w 5) | .08 | −.03 | .04 | .14 † | .08 | .25 ** | .12 | .33 ** | .21 * | .16 * | — | 13.28 | 3.25 |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Mean (men) | 43.75 | 18.42 | .66 | 35.34 | 11.57 | 48.79 | 3.89 | 7.67 | 8.37 | 13.98 | 13.23 | ||

| S.D (men) | 7.63 | 3.88 | .86 | 10.15 | 3.13 | 11.69 | 2.02 | 2.25 | 2.69 | 2.32 | 3.49 | ||

p ≤ .01;

p ≤ .05,

p<.10 (two-tailed tests)

Correlations for women (listwise n = 195) displayed above the diagonal; correlations for men (listwise n = 141) displayed below the diagonal.

It should be noted that, for men and women, the mean for negative view of marriage was slightly lower at wave 5 than wave 4. The variance, however, was higher at wave 5 than wave 4. It increased from 2.32 to 3.49 for men and from 2.49 to 3.25 for women. Thus, while overall the respondents showed a less negative view of marriage as they move into adulthood, there was much variability in this pattern. The theoretical model to be tested suggests that in large measure it was differential experiences in romantic relationships that account for this increased variation in beliefs about marriage.

As noted above, SEM (MPLUS 3.0, Muthen & Muthen, 2004) was used to test the model presented in Figure 1. The N for this modeling was slightly higher than that for the listwise correlations reported in Table 1 as MPLUS allows imputation of missing data in the SEM using the full maximum likelihood (FIML) method. The FIML approach is unbiased and provides more power than the listwise procedure. It assumes that missing data are randomly distributed and are unrelated to the dependent variable (Graham, 2009). This assumption is met in the FACHS sample as missing data are derived from the random attrition associated with a longitudinal design.

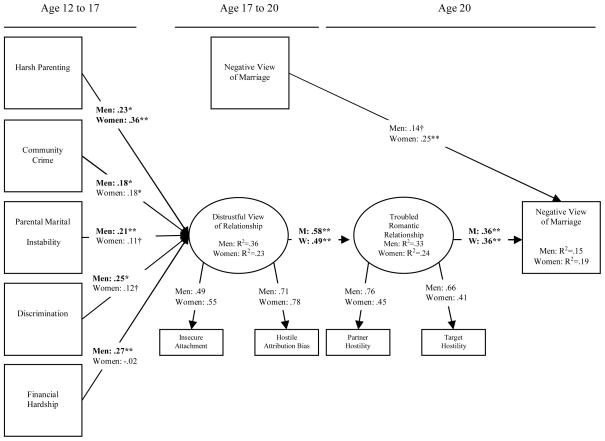

We began by running the fully recursive models separately for men and women. A number of the associations did not approach significance. In order to obtain more parsimonious models, we performed the analyses again but only included paths with a t ≥ 1.0. The chi-square difference between the fully recursive and reduced models did not approach statistical significance indicating that the reduced model provided a more parsimonious fit. Figure 2 presents the reduced models for men and women, respectively. The various fit indices suggested that for both men and women the reduced models provide a good fit of the data.

Figure 2.

Reduced Structural Model of Pathways for both Men (n=159) and Women (n=221)

**p ≤ .01; *p ≤ .05, †p<.10 (two-tailed tests)

Note: Males: χ2=36.05, df=27, p=.11. RMSEA=.05, CFI=.95; Females: χ2=32.61, df=27, p=.21. RMSEA=.03, CFI=.98. The values presented are standardized parameter estimates, and missing data are handled by FIML. The bold words indicate that the test of mediating effect is significant.

Beginning with the men, the results shown in Figure 2 indicate that harsh parenting, community crime, family instability, discrimination, and financial hardship are all significant predictors of a distrustful view of relationships. Together, they explain 36% of the variance in men’s distrustful view of relationships. Distrustful view of relationships, in turn, accounts for 33% of the variance (β = .58) in troubled romantic relationship. Finally, being in a troubled romantic relationship predicts change to a less favorable view of marriage. Controlling for earlier views of marriage, troubled romantic relationship has a .36 association with negative view of marriage. Notably, none of the adverse event variables show a direct association with either troubled romantic relationship or negative view of marriage. Rather, their impact upon the latter variables is completely mediated by their effect on men’s perspective on relationships.

Turning to the model for women, Figure 2 shows that harsh parenting (γ = .36) and community crime (γ = .18) are significant predictors of a distrustful view of relationships. The coefficients are positive and approach significance for discrimination and parental marital instability. As was the case for men, a distrustful view of relationships predicts a troubled romantic relationship (β = .49; R2 = .23) which, in turn, predicts changes toward a more negative view of marriage (β = .36; R2 = .24). Also consistent with the findings for men, the effects of the adverse conditions on both troubled romantic relationship and negative view of marriage is limited to their indirect effects through distrustful view of relationships.

The multiple group analysis option in Mplus was used to test for differences between the models for men and women. We began by comparing a model that constrained coefficients for men and women to be equal to a model that freed them to differ. The chi-square difference between the models was significant, indicating that the assumption of structural invariance was not correct. To determine which paths were different, we relaxed one path in the constrained model at a time and compared it with the constrained model’s chi-square with one degree of freedom. Using this procedure, only one path differed significantly by gender. The path from financial hardship to distrustful view of relationships was significantly larger for males (β = .27) than females (β =.02). The difference in the path from discrimination to distrustful view of relationships (β = .25 for males; β = .12 for females) approached significance (p < .15) as did the stability coefficient for negative view of marriage (β = .14 for males; β = .25 for females).

Next, we tested for the significance of the indirect effects depicted in the SEM models. The results are shown in Table 3. For men, harsh parenting, community crime, family instability, discrimination, and financial hardship increase the probability of a troubled romantic relationship through their impact on distrustful view of relationships. These indirect effects are either significant (p ≤ .05) or approach significance (p ≤ .05). Further, distrustful view of relationships exerts a significant indirect effect on negative view of marriage through its impact on troubled romantic relationship. For women, harsh parenting has a significant indirect effect on troubled romantic relationship through distrustful view of relationships and the indirect effect of community crime through distrustful view of relationships approaches significance. Further, the effect of distrustful view of relationships on negative view of marriage through troubled romantic relationship is statistically significant.

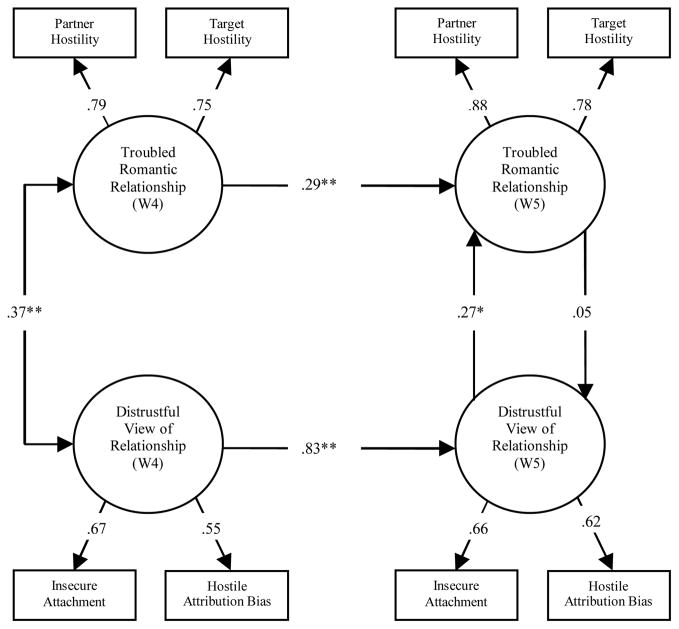

Although the data presented in Figure 1 are consistent with our theoretical model, they do not rule out the viability of various alternative models. First of all, it may be that we have misspecified the causal priority underlying the association between distrustful view of relationships and troubled romantic relationship. It might be that a troubled relationship causes a distrustful view of relationships rather than the reverse as we have argued. To investigate this idea, we tested a reciprocal effects model using data from the 224 individuals who reported being in a romantic relationship at both waves 4 and 5. The results, which are depicted in Figure 3, show that a distrustful view of relationships predicts change in troubled romantic relationship ((β = .27, p < .05) whereas being in a troubled romantic relationship has no significant effect upon change in distrustful view of relationships. These findings support the hypothesis that relational schemas acquired during adolescence influence the quality of early adult romantic relationships, whereas early adult romantic relationships have little impact upon relational schemas.

Figure 3.

Structural equation model showing the reciprocal relationship between distrustful view of relationships and troubled romantic relationship.

Note: χ2=56.90, df=15, p=.00. SRMR=.05, CFI=.91.

**p ≤ .01; *p ≤ .05, †p<.10 (two-tailed tests), n=224

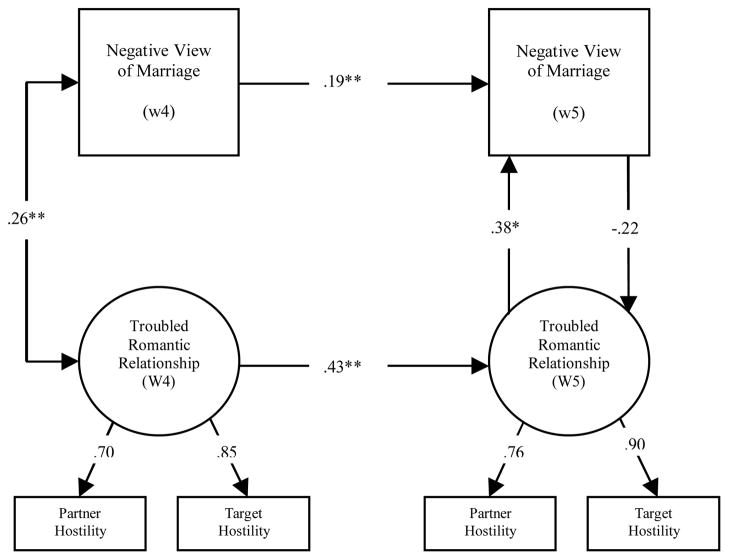

A second consideration involves the relationship between troubled romantic relationship and view of marriage. The SEM model presented in Figure 2 indicated that a troubled romantic relationship fosters a more negative view of marriage. It is possible, however, that a negative view of marriage also leads to a more troubled romantic relationship. Indeed, this latter effect might be larger than the impact of troubled relationship on negative view of marriage. This possibility was also tested using a reciprocal effects model and data from the 224 individuals reporting a romantic relationship at both waves 4 and 5. The results are presented in Figure 4. The figure shows a significant path from troubled romantic relationship to change in negative views of marriage (β = 38, p < .05) whereas there is no significant association between negative view of marriage and change in troubled relationship. Indeed the effect is not even in the expected direction. Thus the model supports the hypothesis that the causal priority is from troubled romantic relationship to negative view of marriage.

Figure 4.

Structural equation model showing the reciprocal relationship between troubled romantic relationship and negative view of marriage

Note: χ2=11.57, df=6, p=.07. SRMR=.02, CFI=.98.

**p ≤ .01; *p ≤ .05, †p<.10 (two-tailed tests), n=224

Finally, one might argue that our analyses are limited in that they focus only upon persons who are in a romantic relationship and that focusing upon those not in a romantic relationship might reveal a different story. Indeed, perhaps those not in a relationship possess very distrustful relational schemas and these schemas operate to impede involvement in romantic relationships while fostering a negative view of marriage. We completed several sets of analyses in an attempt to evaluate these arguments and in every case the results provided support for our theoretical model. To begin, individuals not in a romantic relationship do not possess more distrusting relational schemas than those in a romantic relationship. Further, for those persons not in a romantic relationship, there is no significant association (r = .02) between possessing a distrustful view of relationships and endorsing a negative view of marriage. Importantly, however, there is a significant relation (r = .19, p< .05) between these two constructs for individuals in a romantic relationship. And, as shown in Figure 2, this association is completely mediated (for both males and females) by the construct troubled romantic relationship. This pattern of findings supports our argument that relational schemas begin to influence an individual’s view of marriage as they gain experience in romantic relationships. The nature of this influence is indirect as a distrustful view of relationships increases the probability of a troubled romantic relationship which, in turn, advances a more negative view of marriage.

DISCUSSION

Numerous studies have reported that African Americans are less satisfied with their romantic relationships and are less likely to marry than European Americans (Clayton, Miney, & Blankenhorn, 2003; Fields & Casper, 2001; Sweeney & Phillips, 2004). The present study developed and tested a model that links these two phenomena. The model posits a causal sequence whereby persistent childhood exposure to race-related disadvantages and stressful events gives rise to cynical, distrusting relational schemas that increase the probability of discordant romantic relationships during late adolescence and emerging adulthood, with these relationship difficulties, in turn, promoting a less positive view of marriage. Our findings provided strong support for the model.

These results are important in several respects. First, they suggest another avenue whereby racism and disadvantage contribute to the sharp racial disparities that have come to exist regarding romantic relationships and marriage. Past explanations have tended to emphasize marriage market conditions (Oppenheimer, 1988; Wilson, 1987) and economic hardship (Edin, 2000; Wilson, 1987, 1996). Although these structural factors have been shown to be important, they explain only a small portion of the relationship difficulties and low marriage rates that are evident in many disadvantaged African American communities (Bennett, Bloom, & Craig, 1989; Lichter, McLaughlin, Kephart, & Landry 1992; Crissey, 2005). As a consequence, some have argued that the African American community simply differs from the majority population regarding the meaning of romantic relationships and the importance of marriage (Cherlin, 1992; Crissey, 2005; Sassler & Schoen, 1999). These differences are often seen as a component of black culture. Our findings, however, suggest an alternative perspective. Rather than being cultural meanings that are passed along from adults to children, our data support a model where antagonistic romantic relationships and a reluctance to marry are recreated in each new generation as adverse race-related circumstances foster distrustful relational schemas. These schemas increase the probability of being in a conflicted romantic relationship which, in turn, is associated with adoption of a more cynical view of marriage. This framework identifies another structural mechanism, in addition to economic disadvantage and a poor marriage market, whereby racism and adversity impact romantic relationships and marriage among African Americans.

Beyond this contribution to our understanding of the avenues whereby adverse conditions may impact the romantic relationships of African Americans, findings from the present study contribute more generally to our understanding of the social determinants of relational schemas. Recent research has established that relational schemas influence a wide variety of social behaviors. While the present study focused upon romantic relationships, there is strong evidence that these cognitive frameworks affect our motives, emotions, and behaviors in a wide variety of social settings and relationships (Cassidy & Shaver, 2008; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2010). Most research on the etiology of relational schemas has emphasized the role of child and adolescent experiences in family of origin. However, John Bowlby and Ken Dodge, two important theorists in the area of relational schemas, have emphasized that extrafamilial relationships most likely also play a role in the development of these structures (Bowlby, 1982; Dodge & Pettit, 2003). Findings from the present study support this idea. Beyond the influence of harsh parenting and changes in family structure, we found that persistent exposure to discrimination, crime, and financial strain was associated with the development of a distrustful view of people and relationships. This is consistent with the finding by Mickelson et al. (1997) that financial hardship and criminal victimization are related to insecure attachment as well as with a series of studies by Simons and colleagues linking discrimination (Simons et al. 2002, 2006) and exposure to crime (Simons & Burt, 2011) to the development of a hostile view of relationships. Their findings, combined with those from the present study, suggest that research on relational schemas would do well to pay more attention to extrafamilial determinants of these structures.

It should be noted, however, that there was evidence that two of the extrafamilial influences included in our study differ by gender. The path from financial hardship to distrustful view of relationships was significantly larger for males than females, and the path from discrimination to distrustful view of relationships was also larger for males although the difference only approached significance. It may be that these differences are a function of the fact that historically African American males have been the victims of more negative stereotypes than African American females (Anderson, 1999; Majors & Billson, 1992; Young, 2004). Black men are often seen as untrustworthy, shiftless, uneducated, criminal and dangerous and such views foster discrimination in many areas of life including the economic sector (Majors & Billson, 1992; Young, 2004). Consonant with this idea, males in the present study reported significantly higher levels of discrimination than females. Thus it may be that African American males encounter higher levels and more serious forms of discrimination than females, with the result being that discriminatory events have more of an impact upon their relational schemas that those of African American females. Further, given these gender differences in discrimination, it may be that African American men tend to perceive financial hardship to be a consequence of discrimination and unfair treatment whereas African American women are more likely to perceive it as a result of unfortunate circumstances, bad luck or fate. To the extent that this is true, economic difficulties would be expected to have more of an effect upon males’ than females’ perceptions of people and relationships.

While these gender differences are interesting, they should not overshadow the fact that the general model was supported for both men and women. Overall, the findings are consistent with a life course model where the cognitive and psychological consequences of race-related stressors and disadvantages experienced during childhood and adolescent reverberate across the life course, exerting a disruptive effect on romantic relationships. Chronic exposure to adverse conditions such as harsh parenting, family instability, discrimination, economic hardship, and crime increase the chances that African American youth will develop negative relational schemas that promote conflict and hostility with romantic partners. Stormy, conflict ridden dating relationships, in turn, given rise to unflattering perceptions of the costs and benefits of marriage.

The FACHS data used in the present study afforded several advantages such as repeated assessments of a wide variety of constructs over a several year period. However, there were also limitations inherent in the data and two of these were particularly salient given the model being tested. First, only African Americans were included in the sample. Past research has shown that in general African Americans are more likely than European Americans to experience various adverse social conditions, and our analyses demonstrated an association between these adverse conditions and the development of relational schemas, relationship discord, and negative views of marriage among the respondents in our African American sample. However, because the sample only consisted of African Americans, we were unable to examine the extent to which differences between African Americans and European Americans with regard to the adverse conditions in our model explain the gap between the two groups in relational schemas, relationship difficulties, and views of marriage. Such analyses require a more racially/ethnically diverse sample.

A second major limitation of our study is that the subjects are just entering early adulthood and therefore we have no way of knowing the extent to which the quality of their romantic relationships and their attitudes about marriage will impact adult union formation. Past research, however, has shown that beliefs and attitudes do exert a modest influence on behavior (Ajzen & Fishbein, 2005) and therefore it seems likely that those with a negative view of marriage will be less likely to marry. Further, as noted earlier, teen romantic relationships often serve as a training ground for adult intimate relationships. Studies show that hostile and violent romantic relationships during late adolescence tend to portend similar relationship dynamics in adulthood (Conger et al., 2001; O’Leary, 1988; O’Leary et al., 1989). This suggests that those individuals in our sample who reported high conflict and dissatisfaction in their current dating relationships are at risk for troubled, unstable adult romantic relationships. Such relationship difficulties might be expected to result in a reduced inclination to marry and, for those who do marry, an increased probability of conflict and divorce. Subsequent waves of data will allow us to examine these expectations.

It is essential, of course, that other researchers replicate our findings concerning the effect of race-related stressors upon insecure attachment and teen romantic relationships. Further, future research needs to investigate the associations that we suggested but were not able to test regarding the impact of teen romantic relationships and perceptions of marriage on adult marital behavior. To the extent that our predictions are corroborated by others, they suggest a new avenue whereby race-related strains such as discrimination, exposure to crime, and economic hardship influence adult union formation. These strains foster negative relational schemas that have a disruptive effect upon teen and adult romantic relationships and beliefs about the rewards and costs of marriage.

Table 2.

Significance of the Indirect Effects for Theoretical Models

| Predictors | Mediatior | Outcomes

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Troubles Romantic Relationship

|

Negative View of Marriage

|

||||

| Men | Women | Men | Women | ||

| Harsh Parenting | Distrustful View of Relationships | .13 † | .18 * | ||

| Community Crime | Distrustful View of Relationships | .11 † | .09 † | ||

| PC’s marital instability | Distrustful View of Relationships | .12 * | .06 | ||

| Discrimination | Distrustful View of Relationships | .14 * | .06 | ||

| Financial Hardship | Distrustful View of Relationships | .15 * | .02 | ||

| Distrustful View of Relationships | Troubled Romantic Relationship | .21 ** | .18 * | ||

p ≤ .01;

p ≤ .05 (two-tailed tests). The values presented are standardized parameter estimates

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (MH48165, MH62669) and the Center for Disease Control (029136-02). Additional funding for this project was provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (1P30DA027827) and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (2R01AA012768, 3R01AA012768-09S1). Direct all correspondence to Dr. Ronald L. Simons, Department of Sociology, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602 (rsimons@uga.edu).

Footnotes

The Experience of Close Relationships scale includes subscales that can be used to differentiate avoidant and anxious attachment. However, these two subtypes of insecure attachment are highly correlated (Chisholm, Quinlivan, Petersen, & Coall, 2005) as both are based upon a cynical, distrustful view of others. Thus in the present study we sum across the subscales to form a single measures of insecure attachment, an approach often used in prior research (Chisholm et al., 2005). This strategy is supported by the fact that that in the present study the scale items loaded on a single factor (all loadings were above .5).

Contributor Information

Ronald L. Simons, Email: rsimons@uga.eud, Department of Sociology, University of Georgia

Leslie Gordon Simons, Email: lgsimons@uga.edu, Department of Child and Family Development, University of Georgia.

Man Kit Lei, Email: karlo@uga.edu, Department of Sociology and Center for Family Research, University of Georgia.

Antoinette Landor, Email: antoinettelandor@yahoo.com, Department of Child and Family Development, University of Georgia.

References

- Ajzen I, Fishbein M. The influence of attitudes on behavior. In: Albarracin D, Johnson BT, Zanna MP, editors. The handbook of attitudes. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2005. pp. 173–221. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson E. Street wise. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson E. Code of the streets: Decency, violence, and the moral life of the inner city. New York: W. W. Norton & Company; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Bakermans-Dranenburg MJ, van Ijzendoorn MH, Kroonenberg PM. Differences in attachment security between African-American and white children: ethnicity or socio-economic status? Infant Behavior and Development. 2004;27:417–433. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey CA, Ostrov JM. Differenting forms of functions of aggression in emerging adults: Associations with hostile attribution biases and normative beliefs. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2008;37:713–722. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin JM. Relational schemas and the processing of social information. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112:461–484. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett NG, Bloom DE, Craig PH. The divergence of black and white marriage patterns. American Journal of Sociology. 1989;95:692–722. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107(2):238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block JH. Differential premises arising from differential socialization of the sexes: Some conjectures. Child Development. 1983;54(6):1335–1354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan KA, Clark CL, Shaver PR. Self-report measurement of adult attachment: An integrative overview. In: Simpson JA, Rholes WS, editors. Attachment theory and close relationships. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1998. pp. 46–76. [Google Scholar]

- Bretherton I, Munholland KA. Internal working models in attachment relationships: A construct revisited. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. pp. 89–111. [Google Scholar]

- Brown BB, Feiring C, Furman W. The development of romantic relationships in adolescence. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Brown MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociological Methods and Research. 1992;21:230–258. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment. Vol. 1. New York: Basic Books; 1969. Attachment and loss. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Separation: Anxiety and anger. Vol. 2. New York: Basic Books; 1973. Attachment and loss. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment. 2. Vol. 1. New York: Basic Books; 1982. Attachment and Loss. [Google Scholar]

- Burton L, Jarrett RL. In the mix, yet on the margins: The place of families of color in urban neighborhood and child developmental research. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2000;62:1114–1135. [Google Scholar]

- Butzer B, Campbell L. Adult attachment, sexual satisfaction, and relationship satisfaction: A study of married couples. Personal Relationship. 2008;15:141–154. [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh SE, Crissey SR, Raley RK. Family structure and adolescent romance. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2008;70:698–714. [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin AJ. Social trends in the United States. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1992. Marriage, Divorce, Remarriage (rev. and enl. Edu) [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm JS, Quinlivan JA, Petersen RW, Coall DA. Early stress predicts age at menarche and first birth, adult attachment, and expected lifespan. Human Nature. 2005;16(3):233–265. doi: 10.1007/s12110-005-1009-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton O, Mincy RB, Blankenhorn D, editors. Black fathers in contemporary American society. NY: Russell Sage; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Collins N. Working models of attachment: Implications for explanation, emotion, and behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;71:810–832. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.71.4.810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins NL, Read SJ. Adult attachment, working models, and relationship quality in dating couples. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;58(4):644–663. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.58.4.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins NL, Ford MB, Guichard AC, Allard LM. Working models of attachment and attribution processes in intimate relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2006;32:201–219. doi: 10.1177/0146167205280907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Ming G, Bryant CM. Competence in early adult romantic relationships: A developmental perspective on family influences. Prevention and Treatment. 2001;4:1–25. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.2.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Dodge KA. A review and reformulation of social information-processing mechanisms in children’s social adjustment. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;115:74–101. [Google Scholar]

- Crissey SR. Race/ethnic differences in marital expectations of adolescents: The role of romantic relationships. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:697–709. [Google Scholar]

- Crowell JA, Fraley RC, Shaver PR. Measurement of individual differences in adolescent and adult attachment. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1999a. pp. 434–465. [Google Scholar]

- Cui M, Lorenz FD, Conger RD, Melby JN, Bryant CM. Observer, self-, and partner reports of hostile behaviors in romantic relationships. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:1169–1181. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA. Social cognition and children’s aggressive behavior. Child Development. 1980;51:162–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA. A social information processing model of social competence in children. In: Perlmutter M, editor. Minnesota Symposium on Child Psychology. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1986. pp. 77–125. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS. Mechanisms in the cycle of violence. Science. 1990;250:1678–1683. doi: 10.1126/science.2270481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Newman JP. Biased decision-making processes in aggressive boys. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1981;90(4):375–379. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.90.4.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Pettit GS. A biopsychosocial model of the development of chronic conduct problems in adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:349–371. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.39.2.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnellan MB, Assad KK, Robins RW, Conger RD. Do negative interactions mediate the effects of negative emotionality, communal positive emotionality, and constraint on relationship satisfaction? Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2007;24(4):557–573. [Google Scholar]

- Edin K. What do low-income mothers say about marriage. Social Problems. 2000;47:112–33. [Google Scholar]

- Epps J, Kendall PC. Hostile attributional bias in adults. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1995;19(2):159–178. [Google Scholar]

- Feeney JA, Noller P, Callan VJ. Attachment style, communication and satisfaction in the early years of marriage. In: Bartholomew K, Perlman D, editors. Attachment processes in adulthood. Advances in personal relationships. London, England: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 1994. pp. 269–308. [Google Scholar]

- Feeney JA. Adult romantic attachment and couple relationships. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press; 1999. pp. 355–377. [Google Scholar]

- Feeney JA. Adult romantic attachment: Developments in the study of couple relationships. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications. 2. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 456–481. [Google Scholar]

- Fields J, Casper LM. Current Population Reports. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2001. America’s families and living arrangements: March 2000; pp. P20–537. [Google Scholar]

- Fite JE, Bates JE, Holtzworth-Munroe A, Dodge KA, Nay SY, Pettit GS. Social information processing mediates the intergenerational transmission of relationship conflict. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:367–376. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.3.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraley RC, Waller NG, Brennan KA. An item response theory analysis of self-reports measures of adult attachment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78:350–365. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.2.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo LC, Smith TW. Attachment style in marriage: Adjustment and responses to interaction. Journal of Social and Personal Relationship. 2001;18:263–289. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Cleveland MJ, Wills TA, Brody G. Perceived discrimination and substance use in African American parents and their children: a panel study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;86:517–529. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.4.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein JR, Kinney CT. Marriage delayed or marriage forgone? New cohort forecasts of first marriage for U.S. women. American Sociological Review. 2001;66:506–519. [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW. Missing data analysis: Making it work in the real world. Annual Review of Psychology. 2009;60:549–576. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampton RL, Gelles RJ, Harrop JW. Is violence in Black families increasing? A comparison of 1975 and 1985 national survey rates. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1989;51:969–980. [Google Scholar]

- Holzworth-Munroe A. A typology of men who are violent toward their female partners: Making sense of the heterogeneity in husband violence. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2000;9(4):140–143. [Google Scholar]

- Jin X, Eagle M, Keat JE. Hostile attributional bias, early abuse, and social desirability in reporting hostile attributions among chinease immigrant batters and nonviolent men. Violence and Victims. 2008;23(6):773–786. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.23.6.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurdek LA. Differences between partners from Black and White heterosexual dating couples in a path model of relationship commitment. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2008;25:51–70. [Google Scholar]

- Landrine H, Klonoff EA. The schedule of racist events: A measure of racial discrimination and a study of its negative physical and mental health consequences. Journal of Black Psychology. 1996;22:144–168. [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Dodge KA, Pettit GS, Bates JE, Crozier J, Kaplow J. A 12- year prospective study of the long-term effects of early child physical maltreatment on psychological, behavioral, and academic problems in adolescence. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2002;156:824–830. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.8.824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy MB, Davis KE. Love styles and attachment styles compared: Their relations to each other and to various relationship characteristics. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1988;5:439–471. [Google Scholar]

- Lichter DT, McLaughlin DK, Kephart G, Landry DJ. Race and the retreat from marriage: A shortage of marriageable men? American Sociological Review. 1992;57(6):781–799. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon-Lewis C, Lamb ME, Hattie J, Baradaran LP. A longitudinal examination of the associations between mothers’ and sons’ attribution and their aggression. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:69–81. doi: 10.1017/s0954579401001055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC, Cauce AM, Takeuchi D, Wilson L. Marital processes and parental socialization in families of color: A decade of research. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2000;62:1070–1093. [Google Scholar]

- Mickelson KD, Kessler RC, Shaver PR. Adult attachment in a nationally representative sample. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;73(5):1092–1106. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.73.5.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. MPLUS user’s guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson DA, Crick NR. Rose-colored glasses: Examining the social information-processing of prosocial young adolescents. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1999;19:17–38. [Google Scholar]

- Oggins J, Veroff J, Leber D. Perceptions of marital interaction among Black and White newlyweds. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;65:493–511. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.65.3.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheimer VK. Women’s rising employment and the future of the family in industrial societies. Population and Development Review. 1994;20(2):293–342. [Google Scholar]

- O’ Leary KD. Physical aggression between spouses: A social learning theory perspective. In: Van Hasselt VB, Morrison RL, Bellack AS, Hersen M, editors. Handbook of Family Violence. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1988. pp. 31–56. [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary KD, Barling J, Arias I, Rosenbaum A, Malone J, Tyree A. Prevalence and stability of physical aggression between spouses: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1989;57(2):263–268. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.57.2.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheimer VK. A theory of marriage timing. American Journal of Sociology. 1988;94(3):563–591. [Google Scholar]

- Orobio de Castro B, Veerman JW, Koops N, Bosch JD, Monshouwer HJ. Hostile attribution of intent and aggressive behavior: A meta-analysis. Child Development. 2002;73(3):916–934. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce ZJ, Halford WK. Do attributions mediate the association between attachment and negative couple communication? Journal of Personal Relationships. 2008;15(2):155–170. [Google Scholar]

- Pinderhughes EE, Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS, Zelli A. Discipline responses: Influences of parents’ socioeconomic status, ethnicity, beliefs about parenting, stress, and cognitive-emotional processes. Journal of Family Psychology. 2000;14(3):380–400. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.14.3.380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raley RK, Crissey SR, Muller C. Of sex and romance: Late adolescent relationships and young adult union formation. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2007;69:1210–1226. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00442.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rennison M, Welchans S. Intimate partner violence. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2000. May, Special Report. [Google Scholar]

- Runions KC, Keating DP. Young children’s social information processing: Family antecedents and behavioral correlates. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43(4):838–849. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.4.838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science. 1997;277:918–924. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassler S, Schoen R. The Effect of Attitudes and Economic Activity on Marriage. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1999;61:147–159. [Google Scholar]

- Shulman S, Scharf M. Adolescent romantic behaviors and perceptions: Age- and gender-related differences, and links with family and peer relationships. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2000;10:99–118. [Google Scholar]

- Simons LG, Simons RL, Burt CH. A test of explanations for the effect of harsh parenting on the perpetration of dating violence and sexual coercion among college men. Violence & Victims. 2008;23(1):66–82. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.23.1.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Burt CH. Learning to be bad: Adverse social conditions, social schemas and crime. Criminology. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.2011.00231.x. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Simons LG, Burt CH, Drummund H, Stewart E, Brody GH. Supportive parenting moderates the effect of discrimination upon anger, hostile view of relationships, and violence among African American boys. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2006;47:373–389. doi: 10.1177/002214650604700405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Simons LG, Chen Y, Brody GH, Lin K. Identifying the psychological factors that mediate the association between parenting practices and delinquency. Criminology. 2007;45:481–518. [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Murry V, McLoyd V, Lin K, Cutrona C, Conger RD. Discrimination, crime, ethnic identity, and parenting as correlates of depressive symptoms among African American children: A multilevel analysis. Development and Psychopathology. 2002;14(2):371–393. doi: 10.1017/s0954579402002109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Simons LG, Burt CH, Drummund H, Stewart E, Brody GH, Gibbons FX, Cutrona C. Supportive parenting moderates the effect of discrimination upon anger, hostile view of relationships, and violence among African American boys. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2006;47(4):373–389. doi: 10.1177/002214650604700405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson JA, Rhodes WS, Phillips D. Conflict in close relationships: An attachment perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;71:899–914. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.71.5.899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney MM, Phillips MA. Understanding racial differences in marital disruption: Recent trends and explanations. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004;66:239–50. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RA. Early attachment and later development. In: Cassidy J, Shaver P, editors. Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1999. pp. 348–365. [Google Scholar]

- Vitale JE, Newman JP, Serin RC, Bolt DM. Hostile attributions in incarcerated adult male offenders: An exploration of diverse pathways. Aggressive Behavior. 2005;31(2):99–115. [Google Scholar]

- White L, Rogers SJ. Economic circumstances and family outcomes: A review of the 1990s. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2000;62:1035–1051. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson WJ. When work disappears. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson WJ. The woes of the African American inner-city father. In: Clayton O, Mincy RB, Blankenhorn D, editors. Black fathers in contemporary American society. New York: Sage; 2003. pp. 9–29. [Google Scholar]

- Wood AH, Eagly AH. A cross-cultural analysis of the behavior of women and men: Implications for the origins of sex differences. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128(5):699–724. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.5.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]