Abstract

Using typologies outlined by Gottman and Fitzpatrick as well as institutional and companionate models of marriage, the authors conducted a latent class analysis of marital conflict trajectories using 20 years of data from the Marital Instability Over the Life Course study. Respondents were in one of three groups: high, medium (around the mean), or low conflict. Several factors predicted conflict trajectory group membership; respondents who believed in lifelong marriage and shared decisions equally with their spouse were more likely to report low and less likely to report high conflict. The conflict trajectories were intersected with marital happiness trajectories to examine predictors of high and low quality marriages. A stronger belief in lifelong marriage, shared decision making, and husbands sharing a greater proportion of housework were associated with an increased likelihood of membership in a high happiness, low conflict marriage, and a decreased likelihood of a low marital happiness group.

Keywords: marital confict, marital quality, marriage, latent class analysis, life course

Marital conflict and satisfaction have been the subject of years of marital research. Yet the focus of this research has been quite different for each measure of marital quality. Marital satisfaction is most often the outcome in longitudinal research on marriage, whereas marital conflict has mostly been an independent variable. Indeed, in Karney and Bradbury’s (1995) review and meta-analysis of 115 longitudinal studies of marital quality and stability, not a single study included marital conflict as the dependent variable. Rather, marital conflict, primarily measured as conflict behavior, was an independent variable in 18 of the longitudinal studies reported. The focus on marital satisfaction as an outcome has meant that researchers have not yet examined longitudinal patterns of change in marital conflict over time.

Marital satisfaction has been found to decline even into the later years of marriage (Glenn, 1998; VanLaningham, Johnson, & Amato, 2001). But what happens to marital conflict over time? We examine the pattern of change in the frequency of marital conflict in six waves of data collected over the 20 years of the Marital Instability Over the Life Course Study. Because it is likely that not all couples change in one dominant pattern, we use latent class analysis (LCA) to test whether any subgroups of spouses maintain low or high levels of conflict over 20 years. We also examine the role of individual, behavioral, and contextual variables in predicting patterns of change in marital conflict. Finally, we use data on marital happiness to compare trajectories of change in marital happiness to marital conflict and to predict membership in high quality, that is, high marital happiness and middle to low conflict marriages, as compared with low quality, that is, low marital happiness, marriages.

Marital Quality Across the Life Course

Several studies have examined how marital quality, as measured by marital satisfaction, changes over time (e.g., Karney & Bradbury, 1995; VanLaningham et al., 2001). VanLaningham et al. (2001), using the Marital Instability Over the Life Course data, found a slightly curvilinear relationship between marital happiness and marital duration with steep declines in marital happiness occurring in the earliest and latest years of marriage. Some research has sought to distinguish subgroups of spouses who do not fit into one-size-fits-all models of marital quality. Psychologists Beach, Fincham, Amir, and Leonard (2005) argued that marital satisfaction should be conceptualized as a categorical variable; their taxometric analysis found about 20% of couples were dissatisfied and 80% of couples were satisfied 2 years after marriage. These subgroups of couples were masked in studies where overall trends in marital satisfaction are examined. Their results were confirmed in work across marriages of varying durations observed for 20 years by Kamp Dush, Taylor, and Kroeger (2008). They found that 38% of couples were in a relatively stable high marital happiness trajectory over time and 41% were in a largely stable middle marital happiness trajectory. Only 22% of couples were in a low marital happiness trajectory.

It might be assumed that marital conflict and marital satisfaction would change in similar ways because they both measure different aspects of a larger construct, marital quality. But marital researchers have argued that marital conflict and marital satisfaction are correlated but distinct constructs themselves (Heyman, Sayers, & Bellack, 1994; Johnson, White, Edwards, & Booth, 1986; Sher & Weiss, 1991). That said, there is little longitudinal research on marital conflict. First, most marital psychologists measure marital conflict as marital problem-solving behavior during marital interactions. These kinds of data are both expensive and difficult to collect as well as very labor intensive to code. Thus, many longitudinal studies of marriage (Gottman, Coan, Carrere, & Swanson, 1998; Huston, Caughlin, Houts, Smith, & George, 2001) conduct marital observations at the first data collection point, or at the first few, but later only measure marital satisfaction and stability as these are more easily and inexpensively measured and analyzed (for an exception, see Clements, Stanley, & Markman, 2004).

A second issue is that often measures of marital satisfaction contain measures of marital conflict. Fincham and Beach (1999) argued that clarity needs to come to the measurement of marital quality because many marital satisfaction questionnaires include items measuring the frequency of conflict. The Dyadic Adjustment Scale (Spanier, 1976), one of the most popular measures of marital satisfaction, includes a frequency of conflict question: “How often do you and your partner quarrel.” Another popular measure of marital satisfaction, the Marital Adjustment Test (Locke & Wallace, 1959), asks the frequency of disagreements on seven topics including friends and sex. Fincham and Beach (1999) point out that the association between marital satisfaction and observed conflict may simply show that “spouses behave in the way they say they do” (p. 58). Thus, marital conflict or disagreements have previously been analyzed as part of analyses examining the patterns of change in marital satisfaction over time but have not been broken apart from satisfaction. The only exception we could find was the work of Umberson, Williams, Powers, Liu, and Needham (2006). Examining 8 years of data from the American Changing Lives panel, growth curve analyses suggested that couples increased in negative interaction (as measured by frequencies of feeling “bothered or upset” by one’s marriage and of “unpleasant disagreements or conflicts”) across the 8 years of the study.

Thus, we might expect that conflict would increase across our study. However, we use the typology of married couples outlined first by Fitzpatrick (1988) and extended by Gottman (1993) to first predict how marital conflict will change over time and next to propose three subgroups of couples. Then, using the Institutional and Companionate models of marriage, we hypothesize which predictors will be associated with the highest and lowest quality marriages in models where we combine trajectories of happiness and conflict.

Predicting the Longitudinal Course of Marital Conflict

Fitzpatrick (1988) and Gottman (1993) both proposed typologies of married couples based on observed marital problem-solving conversations, wherein couples were instructed to identify a problem in their marriage and attempt to resolve it over a period of time. The interaction is videotaped and later coded for a variety of negative and positive conflict behaviors. Though these data are very different from the frequency of conflict variable used in this study, the typologies derived from observational marital research can easily be extended to the study of marital conflict in the larger population, as the frequency of conflict was discussed in each type of couple identified.

Subgroups of marital conflict over time

The first type of couple outlined by Fitzpatrick (1988) and Gottman (1993) was the volatile or independent couple. These types of couples tended to not only have high levels of conflict but also high levels of positive behaviors. They often disclosed both positive and negative feelings. The hostile-engaged couple outlined by Gottman also had higher levels of conflict but exhibited low levels of positive behaviors. Based on the volatile and hostile-engaged couple typologies, we expect a stable, high conflict group trajectory of couples to exist in our data.

Another couple type outlined by both Fitzpatrick (1988) and Gottman (1993) was the traditional or validator couple. Validator couples tended to avoid conflict except for the most important issues in their marriage. Even when conflict did occur, these couples tended to validate each other during the conflict so that the conflict had positive elements as well. Thus, we expect a stable, middle conflict group trajectory as well. Of the two final types of couples, one was found in both Fitzpatrick and Gottman—the separate or avoider couple. Avoider couples tended to minimize conflict and avoid it all together and were characterized by low levels of companionship and higher levels of separateness. A final type of couple identified by Gottman was the hostile-detached couples. These couples also avoided conflict and led more separate lives, but they did get into brief but severe conflicts. Gottman actually found the hostile-detached couples to be more negative and less positive than the hostile-engaged couples who had more conflict. Given the avoider and hostile-detached typologies, we expect to find a stable, low-level conflict group trajectory as our final trajectory.

Overall, then, we expect to find three trajectories—high, middle, and low conflict—that are largely stable over time. But, as can be seen from the typologies of Gottman (1993) and Fitzpatrick (1988), conflict in and of itself is not negative. Indeed, some conflict is probably healthier for a marriage than a lack of conflict. Thus, although we do predict conflict trajectory membership, trajectories of conflict are probably best examined in conjunction with marital satisfaction, measured as marital happiness in this study. Assuming we find three trajectories of conflict as predicted, we plan to intersect them with trajectories of marital happiness, replicated from Kamp Dush et al. (2008). Thus, we would have nine combinations of marital happiness/marital conflict groups, a (hypothesized) high, middle, and low conflict trajectory group for each marital happiness trajectory group (high, middle, and low).

Extending Gottman and Fitzpatrick’s typologies to the marital happiness/ marital conflict groups, we expect to find the five typologies discussed earlier in our data. The volatile couples will be evidenced in the high happiness/high conflict and middle happiness/high conflict groups. Validator couples would most likely be in high happiness/middle conflict and middle happiness/middle conflict groups. On the other hand, we expect avoider couples to be in the high happiness/low conflict group. The low happiness/high conflict and low happiness/middle conflict groups will represent the hostile-engaged couples, whereas the hostile-detached couples will be represented by the low happiness/ low conflict group. Next, we use the institutional versus companionate models of marriage to predict which couples are in low conflict trajectories versus high conflict trajectories.

An institutional model of marriage

Marital researchers have argued that marital quality is influenced by institutional factors associated with marriage (Wilcox & Nock, 2006). Wilcox and Nock have argued that spouses who believe in the institution of marriage, and who have more barriers to exiting marriage, will have higher quality marriages. That is, spouses who strongly believe in the institution of marriage and have many constraints to exiting marriage will have more satisfying marriages, because they will modify their perceptions upward (reflecting a more positive marriage). Constraints include age (older spouses will have a smaller pool from which to find an alternative partner), un- and underemployment, high religiosity, and children.

Wilcox and Nock (2006) also argue that the institutional ideal of marriage may also promote marital happiness by decreasing spousal monitoring of the way their marriage serves their own interests. That is, spouses in institutional marriages may be more altruistic in their perceptions and behaviors and less annoyed when their spouse engages in self-serving behavior. Wilcox (2004) found that some Americans conceptualize their marriages along institutional lines, perceiving their marriage as a sacred institution that is more important than the individual interests of each partner. Spouses who have more characteristics associated with an institutional view of marriage may report less conflict over time and higher overall marital quality.

In support of this model, women with more traditional gender attitudes have happier marriages (Amato & Booth, 1995; Wilcox & Nock, 2006). Women do a majority of housework and child care (Bianchi, Robinson, & Milkie, 2006), and gender attitudes reinforcing this behavior may help wives cope with the inequity. Spouses with a strong religious orientation tend to espouse the idea that marriage is forever and report more marital happiness than those with a weak religious orientation (Heaton & Pratt, 1990). On the other hand, the children of divorced couples hold less traditional attitudes toward lifelong marriage partly because the experience of parental divorce teaches them that marital commitment can be dissolved (Amato & DeBoer, 2001). Similarly, previously divorced individuals and individuals who live together before marriage are more accepting of divorce and have a lower threshold for problems while also having poorer relationship skills, rendering their new relationships at greater risk of being less satisfying and more conflictual (Axinn & Barber, 1997; Booth & Edwards, 1992; Cohan & Kleinbaum, 2002). Thus, based on the institutional model of marriage, we expect that these variables associated with an institutional view of marriage— that is, associated with conservative attitudes toward marriage and increased barriers to exiting marriage—will predict membership in low marital conflict trajectories as well as membership in low marital conflict with middle or high marital happiness groups.

A companionate model of marriage

In contrast, scholars including Paul Amato (Amato, Booth, Johnson, & Rogers, 2007) have argued that egalitarian marriages have higher marital quality, referred to as the companionate theory of marriage (Wilcox & Nock, 2006). This model of marital quality assumes that marriages are lower in conflict and higher in quality when both partners share equally in the division of household labor and decision making in the household. This model is particularly salient given the changes in gender roles that have evolved in the past 50 to 60 years as women have moved more fully into the work force and have taken less time out of the work force.

Husbands’ lack of participation in housework, even when wives are employed full time (Bianchi et al., 2006), is associated with tension, conflict, and poor marital quality (Frisco & Williams, 2003). Equity theory argues fairness is important in intimate relationships, and spouses in equitable relationships— which may be characterized by joint decision making—have been found to be more satisfied (Walster, Walster, & Berscheid, 1978). In families with many children, these effects may be exacerbated, as more household labor is required (Twenge, Campbell, & Foster, 2003). Female labor force participation not only improves family economic well-being (White & Rogers, 2000) but also increases work–family conflict (Perry-Jenkins, Repetti, & Crouter, 2000). Hence, given the companionate model of marriage, we expect decreased equity in household labor and decision making will be associated with middle or high marital conflict trajectories as well as membership in middle or high marital conflict with low marital happiness groups. Conversely, we expect that increased equity in household labor and decision making will be associated with low or middle marital conflict trajectories and membership in low or middle marital conflict with middle or high marital happiness groups.

The Current Project

In the current project, we used 20 years of nationally representative (of married persons in the United States in 1980) longitudinal data on the same individuals. We used latent class analysis (LCA) to test the existence of divergent trajectories of marital conflict. We first conducted an LCA of marital conflict to examine how marital conflict changes over time and whether one dominant pattern emerges or if subgroups of change appear. We also predicted marital conflict class membership using the multidimensional variables associated with marital quality described above. Our final step was to combine trajectories of marital happiness and marital conflict to create multiple groups and again predict group membership in the intersected groups. Though these data are in many ways ideal for the research questions at hand, one area where these data were wanting was in the lack of a single age– marital cohort. We therefore tested for age and marital duration confounds in our models through the use of control variables and sensitivity analyses.

Data and Method

The analysis was of the study of Marital Instability Over the Life Course (Booth, Johnson, Amato, & Rogers, 2003). Telephone interviewers used a random-digit-dialing procedure to obtain a national sample of 2,033 married individuals 55 years of age and younger in 1980. At Wave 2, in 1983, 1,592 (78 %) of the respondents were successfully reinterviewed. At Wave 3, in 1988, 1,341 (66 %) were reinterviewed. At Wave 4, in 1992, 1,183 (58 %) were reinterviewed. At Wave 5, in 1997, 1,077 (53 %) were reinterviewed. At Wave 6, in 2000, 962 (47 %) of the original respondents were reinter-viewed. Respondents who were male, non-White, remarried, with less education, and with more traditional gender attitudes were more likely to drop out of the sample due either to nonresponse or death. We tested the robustness of our estimates by running our trajectory models with and without the individuals who attritted and used methods that examined all data contributed by individuals before they drop out. The majority (38%) of respondents in our sample remained through Wave 6 in their 1980 marriage, followed by 15% remaining until Wave 2. Respondents exiting their 1980 marriage did so due to divorce (26%), widowhood (6%), or attrition (68%). Of those that attritted through 1997 (data are unavailable on reasons for attrition between 1997 and 2000; n = 155), 54% were not located, 35% refused, 8% had died, and 2% had a health refusal.

Dependent Variables

Marital conflict

Marital conflict was measured by the frequency of disagreements in response to “How often do you disagree with your spouse?” with response options of 1 = never, 2 = rarely, 3 = sometimes, 4 = often, and 5 = very often.

Marital happiness

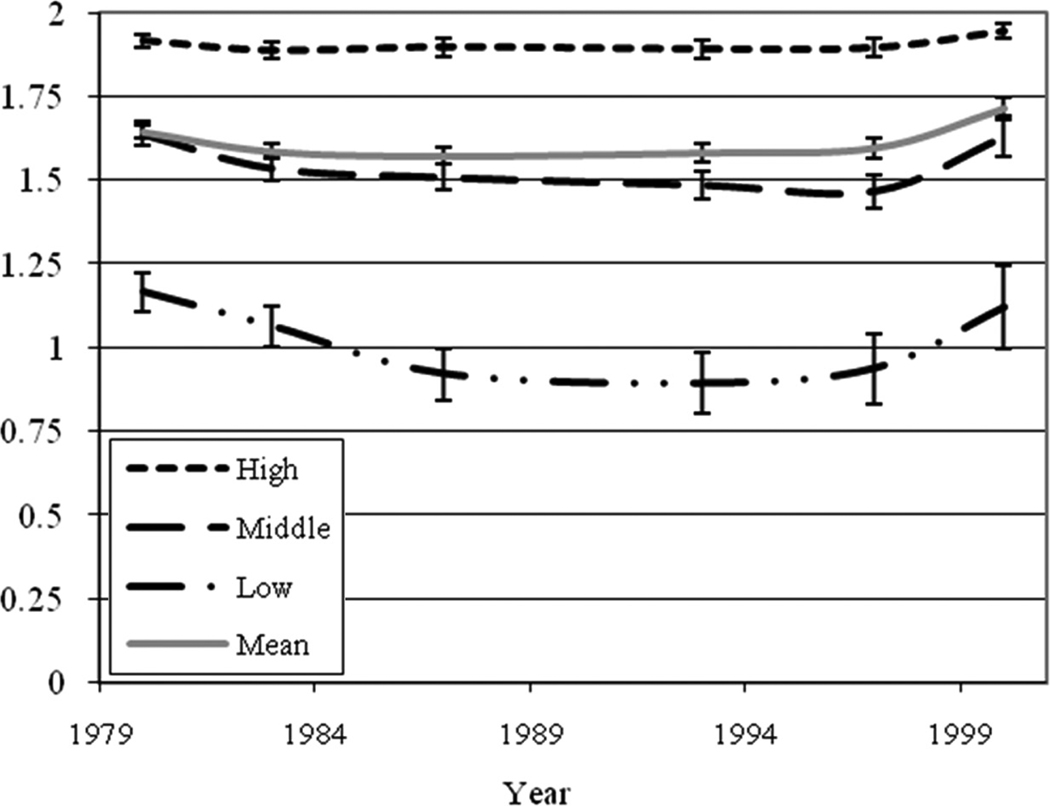

We replicate the marital happiness trajectories established in Kamp Dush et al. (2008). These trajectories are discussed in more detail in Kamp Dush et al.’s work; however, the results of a replication of that LCA are presented here in Table 1 and Figure 1 for comparison purposes. Marital happiness and marital conflict were correlated between –0.31 (Wave 6) and –0.41 (Wave 5) across waves.

Table 1.

Sample Percentages and Means for the Class Trajectories and Overall Sample

| Marital Happiness (N = 1,998) |

Marital Conflict (N = 2,034) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Middle | Low | Overall | SD | High | Middle | Low | Overall | SD | |

| Percentage of sample |

37.81 | 41.10 | 21.09 | 100 | 22.74 | 60.59 | 16.66 | 100 | ||

| Mean 1980 | 1.92 | 1.64 | 1.16 | 1.64 | 0.42 | 3.60 | 2.88 | 2.29 | 2.87 | 0.68 |

| Mean 1983 | 1.89 | 1.54 | 1.06 | 1.58 | 0.43 | 3.57 | 2.91 | 2.30 | 2.87 | 0.66 |

| Mean 1987 | 1.90 | 1.51 | 0.92 | 1.57 | 0.45 | 3.74 | 2.93 | 2.23 | 2.89 | 0.68 |

| Mean 1993 | 1.89 | 1.48 | 0.89 | 1.58 | 0.45 | 3.61 | 2.95 | 2.24 | 2.87 | 0.70 |

| Mean 1997 | 1.89 | 1.47 | 0.94 | 1.60 | 0.44 | 3.46 | 2.86 | 2.22 | 2.80 | 0.68 |

| Mean 2000 | 1.94 | 1.63 | 1.12 | 1.71 | 0.43 | 3.31 | 2.68 | 2.27 | 2.67 | 0.70 |

| L2 (Npar) | 13580.23 (82) | 13607.73 (82) | ||||||||

| Bootstrap p value (SE) |

0.71 (0.02) | 0.35 (0.02) | ||||||||

| BIC | −79681651.68 | −1262.14 | ||||||||

Note: BIC = Bayesian information criterion.

Figure 1.

Marital happiness trajectories, 1980–2000

Description of Covariates

All covariates were measured in 1980 unless noted.

Demographic and family

Marital duration was coded in number of years. Ever divorced was coded as 1 = respondent divorced their 1980 spouse at a future wave, 0 = respondent continuously married. Gender was coded as 1 = wife, 0 = husband. Race was coded as 1 = White, 0 = non-White. Of those who were non-White (22%), 44% were Hispanic, 41% were Black, and 15% were of another race. Age at marriage was coded in years. Parental divorce was coded 1 = parental divorce for either respondent or their spouses, 0 = no parental divorce. Premarital cohabitation was coded as 1 = lived together before marriage, 0 = no premarital cohabitation. Remarriage was coded 1 = second- or higher-order marriage for both respondents and their spouses, 0 = no remarriage. The children less than 18 variable was coded as the maximum number of children less than 18 years old in the household across all waves.

Education and economics

Husband’s education was measured by the husband directly or via the wife’s report and was coded in years. Family income was coded in thousands of 1980 dollars and was logged. Public assistance was coded as a dichotomous variable where 1 = reported any form of public assistance, 0 = no public assistance. Wife’s employment status was measured by two variables, including wife employed full time, coded as 1 = wife employed full time (35–45 hours per week); and wife extended hours, where 1 = wife ever worked extended hours (46+ hours per week). Husband’s and wife’s job demands were measured in response to questions assessing whether the husband’s or wife’s job involved irregular hours, shift work, evening meetings, or overnight trips. The number of job demands was calculated separately for husbands and wives and ranged from 0 to 4. Husband’s employment was coded as 1 = husband unemployed, 0 = husband employed.

Gender relations

Husband’s housework was coded as the proportion of housework done by the husband in response to the query, “In every family there are a lot of routine tasks that need to be done, such as cleaning the house, doing the laundry, cleaning up after meals, cooking dinner, and so on. How much of this kind of work is usually done by you?” Response options included none (0), less than half (.25), about half (.50), more than half (.75), and all of it (1). Depending on the gender of the respondent, we coded the responses as the husband’s share. Equal decision making was coded as “Overall, considering all the kinds of decisions you two make, does your spouse more often have the final word, or do you?” where 1 = responses that referred to compromised or shared decision-making and 0 = dominance by one spouse.

Attitudes and values

Religiosity was measured as “In general, how much do your religious beliefs influence your daily life?” (1 = none; 5 = very much). Traditional gender attitudes was a seven-item scale that included “A woman’s most important task in life should be taking care of her children” (1 = disagree strongly; 2 = disagree; 3 = agree; 4 = agree strongly). All items were scored in the direction of traditional attitudes, and the mean of the responses served as the scale score (α = .71). Support for lifelong marriage was measured with six questions, including “Couples are able to get divorced too easily today” (1 = strongly disagree; 2 = disagree; 3 = agree; 4 = strongly agree). Items were scored in the direction of support for lifelong marriage, and the mean served as the scale score (α = .59).

Steps in the Analysis

To test the number, shape, levels, and sample percentages of marital happiness and conflict trajectories, we use LCA of trajectories. This semiparametric, group-based method uses a multinomial modeling strategy to map group trajectories existing as latent classes (Jones, Nagin, & Roeder, 2001; Land, 2001). Since it is unlikely that the entire population would fall into distinct group trajectories, these models allow for fuzziness while classifying generally distinct groups of experience over age or time (Nagin, 1999). A parametric model of f(y, λ) may be assumed for marital happiness or conflict, where y = (y1, y2, …, yT) is the longitudinal sequence of observed levels of these constructs across T periods. If it is assumed that subgroups exist and differ in parameter values, the model may be rewritten as follows:

In Equation (1), pk is the probability of belonging to class k with corresponding parameter(s) λk, and λk is dependent on time. We created baseline models for marital happiness and marital conflict separately, including controls for marital duration in 1980 and selective attrition through the indicator of divorcing over the 20-year observation period. Tests for time dependence of attrition due to divorce revealed similar results (models not shown).

Next, we introduced predictor variables in models for marital conflict to determine whether factors associated with marital quality vary when tested on model-based trajectories. We were also interested in the intersection of marital happiness and conflict over time as a way to separate out the very best and worst marriages and to see how predictors were associated with the intersection of the two outcomes. We constructed a set of dichotomous variables from the model-estimated modal clusters for the two dependent variables. We computed how trajectories of happiness and conflict covaried in the sample through cross-tabulations and then placed individuals into intersection groups. For example, both a high happiness trajectory and a high conflict trajectory may be predicted for individual i. In this case, the individual would be coded as high happiness–high conflict. Finally, we set up dichotomous variables on happiness–conflict intersections (1 = intersection group; 0 = any other combination) and used a series of logistic regressions to examine how key predictors were associated with the quality of the different combination of happiness and conflict marriages. All data presented are unweighted, since the key predictors used in weighting were included in analyses (see Winship & Radbill, 1994).

Model assumptions and missing data

We performed all latent class and regression analyses using the program Latent Gold 3.0 (Vermut & Magidson, 2004). Since the models employ a multinomial modeling strategy, the assumption of LCA is a categorical dependent variable (assumed by default to be ordinal in Latent Gold; Vermut & Magidson). Analyses of trajectories were replicated using both continuous and categorical (nominal) specifications with no differences in substantive findings. Because of the nature of the outcome variables (scales) and the intuitiveness of interpretation, we present models with an ordinal specification.

The missing data function (default in Latent Gold) computes the likelihood function of each individual given all available information. Therefore, individuals were allowed attrition due to nonresponse while still contributing to the analyses until they dropped out (see Vermut & Magidson, 2004). Less than 1% and no more than 13% of independent variables were missing; therefore, we included individuals who were missing on independent variables.

Results

Table 2 reports means and standard deviations for the covariates at Wave 1 (1980) except where noted. The sample had been married around 13 years in 1980 and 16% of respondents divorced in future waves. The sample included a greater proportion of wives than husbands, was predominantly White, and had an age of marriage around 23 years. A majority had stably married parents, lived apart before marriage, and was in their first marriage. The average number of children less than 18 years in the household was between one and two. The sample was predominantly working and middle class. Husbands had a mean education level of just more than 13 years, and the mean of family income at Wave 1 was $27,451 in 1980 dollars or $70,768 in 2008 dollars (results for log of income reported in Table 2), with few using public assistance. In 1980, about a third of wives were employed full time and few worked extended hours although a majority of husbands were employed. Husbands did about 27% of the housework, and half of the couples made decisions jointly. The sample was above the midpoint on religiosity and had slightly more traditional gender and marital attitudes.

Table 2.

Sample Descriptive Statistics

| Covariates | Mean | SD | Range | % Missing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years married 1980 | 12.56 | 9.19 | 0–38 | 0.25% |

| Divorced 1980–2000 | 0.16 | 0–1 | 0.00% | |

| Female | 0.60 | 0–1 | 0.00% | |

| White | 0.88 | 0–1 | 0.15% | |

| Age married | 22.89 | 5.38 | 14–53 | 0.25% |

| Parental divorce | 0.28 | 0–1 | 0.00% | |

| Premarital cohabitation | 0.16 | 0–1 | 0.25% | |

| Remarriage | 0.20 | 0–1 | 0.00% | |

| Children <18 years | 1.70 | 1.24 | 0–7 | 0.00% |

| Husband’s education | 13.75 | 3.04 | 1–27 | 0.05% |

| Logged household income | 10.10 | 0.51 | 7.8–11.08 | 2.02% |

| Public assistance | 0.10 | 0–1 | 0.29% | |

| Wife full-time work | 0.31 | 0–1 | 0.39% | |

| Wife extended hours | 0.12 | 0–1 | 0.39% | |

| Husband’s job demands | 1.39 | 1.11 | 0–4 | 0.00% |

| Wife’s job demands | 0.48 | 0.84 | 0–4 | 0.00% |

| Husband employed | 0.90 | 0–4 | 0.00% | |

| Husband housework | 0.27 | 0.18 | 0–1 | 0.05% |

| Equal decision making | 0.50 | 0–1 | 0.00% | |

| Religiosity | 3.67 | 1.22 | 1–5 | 0.39% |

| Traditional gender | 2.37 | 0.46 | 1–4 | 0.00% |

| Lifelong marriage | 2.61 | 0.41 | 1–4 | 0.10% |

Note: All covariates measured in 1980 except divorced.

Latent Class Analysis Results

The initial latent class analyses were run controlling for marital duration (an indicator of selective entrance into the sample) and divorced status (an indicator of selective attrition). To analyze which latent class model provided the best fit, we ran models with one to five classes. A three-class model provided the best model fit in terms of various test statistics for marital conflict (χ2 difference test, Bayesian information criterion, Akaike information criterion; see Table 1) and residuals and model parameters (other models not shown).

The model chi-square statistic (L2) used to assess overall model fit represented the relationship between variables unexplained by the model. The p value for the marital conflict model was nonsignificant, representing adequate model fit (p value = .08). Results for the LCA of marital conflict can be seen in Table 1 and Figure 2. In contrast to the overall mean trajectory for marital happiness (shown in Figure 1), we found that the overall mean trajectory for marital conflict was largely stable across the first 12 years of the study and then tapered slightly across the final 8 years. As with marital happiness, the LCA produced three classes. First, we found a high marital conflict group, representing 23% of the sample, where marital conflict had a slight upside-down U-shape; conflict gradually increased across the first 8 years and decreased across the final 12 years. Amato et al. (2007) outlined conventions such that an effect size of less than one fifth of a standard deviation difference between groups is weak, between 0.20 and 0.39 of a standard deviation is moderate, between 0.40 and 0.59 is strong, and an effect size of 0.60 or greater is very strong. Following these conventions, the high conflict group was between 0.9 and 1.3 of a standard deviation above the mean at each time point, indicating a very strong difference between the high conflict group and the mean. The middle marital conflict group, representing 61% of the sample, was right above the mean for marital conflict and was largely stable across the waves, with a slight decline in conflict across the later years of the study. Finally, the low marital conflict group, representing 17% of the sample, had stable low conflict—between 0.6 and almost a full standard deviation below the mean for marital conflict and between 1.5 and 2.2 full standard deviations below the high marital conflict group—indicating a very strong difference between the marriages of the low conflict group and both the middle and high conflict groups. In answer to the first research question—does marital conflict change over time in one dominant pattern or is there a subgroup that remains primarily low in conflict—we found three subgroups (high, medium, and low) of marital conflict trajectories rather than one dominant pattern of marital conflict change. Consistent with Fitzpatrick (1988) and Gottman (1993), we do find more stability in conflict than marital happiness.

Figure 2.

Marital conflict trajectories, 1980–2000

Because we use replicated results from the marital happiness trajectories reported in Kamp Dush et al. (2008) for the intersections discussed, we report the fit statistics (Table 1) and a figure (Figure 1) illustrating the trajectories again here. Because the trajectories are discussed at length in Kamp Dush et al., we limit our discussion of the marital happiness trajectories here.

Predicting Trajectory Membership

Next, we turn to our second question: Do predictors of marital quality predict membership into trajectories of marital conflict? Analyses predicting trajectory membership are reported in Table 3. Odds ratios in Table 3 can be interpreted as the odds of being in a particular marital conflict trajectory compared with being in either of the two other trajectories (i.e., the odds of being in the high marital conflict group vs. being in either the middle or low marital conflict group). Latent Gold is unable to do multinomial logistic regressions (models assuming only one group trajectory as the referent group) at this time. Rather than outputting the classes to a program such as Stata that can handle multinomial logistic regression, we chose to do our analyses in Latent Gold, because in modeling, Latent Gold takes into account that individuals have a likelihood of being in one trajectory over another rather than a strict group membership. That is, group membership is treated as latent rather than observed.

Table 3.

Odds Ratios: Marital Conflict Trajectories (N = 2,024)

| Covariates | High | Middle | Low |

|---|---|---|---|

| Years married 1980 | 1.00 | 0.99*** | 1.01 |

| Divorced 1980–2000 | 1.40*** | 0.95 | 0.75*** |

| Female | 1.14*** | 1.01 | 0.87*** |

| White | 0.88 | 1.01 | 1.13 |

| Age married | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1.02 |

| Parental divorce | 1.10 | 1.03 | 0.88*** |

| Premarital cohabitation | 1.16 | 0.93 | 0.93 |

| Remarriage | 1.06 | 0.91 | 1.04 |

| Children <18 years | 1.06 | 0.97 | 0.97 |

| Husband’s education | 0.99 | 1.01 | 1.00 |

| Logged household income | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Public assistance | 1.09 | 0.93 | 0.98 |

| Wife full-time work | 0.95 | 1.08 | 0.97 |

| Wife extended hours | 1.10 | 0.90 | 1.02 |

| Husband’s job demands | 1.07 | 1.00 | 0.94 |

| Wife’s job demands | 1.08 | 0.94 | 0.98 |

| Husband employed | 0.86 | 1.07 | 1.08 |

| Husband housework | 0.65 | 1.60 | 0.96 |

| Equal decision making | 0.84*** | 1.00 | 1.19*** |

| Religiosity | 1.00 | 0.97 | 1.02 |

| Traditional gender | 0.91 | 1.01 | 1.09 |

| Lifelong marriage | 0.60*** | 1.01 | 1.64*** |

| L2 (Npar) | 13607.73 (82) | ||

| Bootstrap p value (SE) | 0.35 (0.02) | ||

| BIC | −1262.14 |

Note: BIC = Bayesian information criterion.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Many of the traditional predictors of marital quality in the literature were unrelated to marital conflict trajectory membership. Wives had greater odds of being in the high conflict group and lower odds of being in the low conflict group. Respondents whose parents had divorced had smaller odds of membership in the low marital conflict group. No educational or economic outcomes were associated with marital conflict trajectory membership. In contrast to the education and economic outcomes, gender relations were stronger predictors of marital trajectories over time. Spouses in marriages characterized by equal decision making had greater odds of membership in the low marital conflict group. Spouses reporting unequal decision making had greater odds of membership in the high marital conflict groups. Regarding attitudes and values, we found that for each unit increase in a respondent’s support for lifelong marriage, the odds of being in the low marital conflict group increased and the odds of being in the high marital conflict group decreased.

Sensitivity analyses

Results confirm that marital duration and ever divorced status were related to the marital happiness trajectories (reported in Table 4). We found that respondents who were married for more years had smaller odds of being in the middle marital conflict group. We also found that the odds of membership in the high marital conflict group were 40% greater for those who ever divorced across the 20 years of the study as compared with respondents who remained stably married. For those who remained stably married, their odds of membership in the low marital conflict group was greater compared with respondents who eventually divorced.

Table 4.

Cross-Tabulation of Classes (N = 1,998)

| Marital Happiness |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Marital Conflict | High | Middle | Low |

| High | 13.76% | 5.61% | 1.10% |

| Middle | 22.77% | 30.53% | 12.06% |

| Low | 2.05% | 4.30% | 7.81% |

| Pearson chi-square | 380.11*** | ||

| Cramer’s V | 0.31*** | ||

p < .001

We conducted two sets of sensitivity analyses. First, to test for the robustness of our estimates to attrition, we reran our latent class models five additional times for each outcome, marital conflict and marital happiness. The five groups included respondents who contributed data (a) at every wave (n = 951), (b) at five or more waves (n = 1,062), (c) at four or more waves (n = 1,174), (d) at three or more waves (n = 1,324), and (e) at two or more waves (n = 1,575). In all 10 models, the three-cluster model was the best fit to the data. The trajectories of change are virtually identical for each cluster regardless of the sample size and the number of waves of data contributed. Thus, we believe that our estimates are robust even to attrition.

Next, to test for the robustness of our estimates to marital duration, we split our sample into 5-year marital cohorts, that is, those married 1 to 5 years, 6 to 10 years, 10 to 15 years, 20 to 25 years, and 25 to 30 years. In all five marital cohorts, the three-cluster model was the best fit to the data. Overall, though, there was more variation in the marital conflict trajectories when run separately by marital duration as compared with the marital happiness trajectories, though the overall shape was similar for all the cohorts with few exceptions. Given that there was some variation in the overall shape of the marital conflict trajectories by marital duration, we control for marital duration in all models presented in the article.

The Intersection of Marital Happiness and Conflict

Our final research question was: Do predictors of marital quality predict membership into unhappy, high conflict relationships and happy, low conflict relationships—the combination of the happiness and conflict trajectories? In Table 4, we present the cross-tabulation of nine subgroups of marital conflict and marital happiness to identify the highest and lowest quality marriages and the prevalence of the various types of marriages in our sample. Following Gottman (1993) and Fitzpatrick (1988), we find that about 20% of couples were in volatile marriages—about 14% in high happiness/high conflict and 6% in middle happiness/high conflict marriages. In comparison, Gottman found a similar 17% of his community-based sample to be in the volatile typology. We found about 54% of couples were in validator marriages, 23% in high happiness/middle conflict and 31% in middle happiness/middle conflict trajectories. This proportion was much greater than Gottman’s proportion—he found only 19% in validator marriages. About 6% of couples were avoiders, 2% high happiness/low conflict and 4% middle happiness/low conflict. Gottman found a greater proportion of his couples, 15%, to be avoiders. Finally, we found about 20% of the couples were hostile. About 8% were hostile-detached, that is, low happiness/low conflict, and another 13% was hostile-engaged—1% low happiness/high conflict and 12% low happiness/ middle conflict. Gottman found, overall, that 48% of his sample was hostile, with 22% being hostile-engaged and 26% to be hostile-detached. These findings illustrate that when the marital happiness and conflict groups intersected, a more nuanced picture of marriage emerged. Some happily married individuals were fighting often; some unhappily married respondents were rarely fighting. Since marital happiness and conflict do not go hand, making distinctions across multiple dimensions of marital quality is important, as Amato et al. (2007), Gottman (1993), and Fitzpatrick (1988) suggest.

Our next step in the analyses was to predict membership into the nine subgroups. We present the results in Table 5. All the intersection models run using logistic regression in Latent Gold yielded good model fit (p values ranged from .31 to .53). Each column of Table 5 is a separate logistic regression predicting membership in the group identified at the head of each column. Beginning with the validator marriages, we discuss the findings for the high happiness/middle conflict and middle happiness/middle conflict groups. Overall, both groups were less likely to divorce, consistent with Gottman (1993) and Fitzpatrick (1988), who argued that validator marriages would be less likely to divorce. We also found that spouses who were married less time had greater odds of membership in these groups. Spouses married at younger ages and with fewer children under the age of 18 years, as well as those in which husbands helped out with housework and had equal decision making had greater odds of being in the high happiness/middle conflict group. The only other predictor of the middle happiness/middle conflict group was gender—wives had greater odds of being in this group. Overall, validator marriages appeared to be more stable and for high happiness/middle conflict were associated with more egalitarian ideals, consistent with the companionate model of marriage.

Table 5.

Odds Ratios for Happiness and Conflict Combinations (N = 1,989)

| Covariates | Hhap/Hcon | Hhap/Mcon | Hhap/Lcon | Mhap/Hcon | Mhap/Mcon | Mhap/Lcon | Lhap/Hcon | Lhap/Mcon | Lhap/Lcon |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years married 1980 | 0.98 | 0.99*** | 1.01 | 1.00 | 0.99*** | 1.02*** | 1.02*** | 1.01*** | 1.02 |

| Divorced 1980–2000 | 0.74 | 0.67*** | 0.66*** | 0.95 | 0.85*** | 0.81*** | 1.53*** | 1.62*** | 1.75*** |

| Female | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.93 | 1.06 | 1.06*** | 0.87*** | 1.10 | 0.99 | 1.03 |

| White | 0.91 | 1.07 | 1.11 | 0.99 | 1.02 | 1.04 | 0.92 | 0.88*** | 0.95 |

| Age married | 0.98 | 0.98*** | 1.02*** | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.02*** | 1.09*** |

| Parental divorce | 0.97 | 1.01 | 0.91*** | 0.99 | 1.02 | 0.90 | 1.11*** | 1.04 | 0.87 |

| Premarital cohabitation | 1.07 | 0.92 | 0.99 | 1.26*** | 1.00 | 1.03 | 1.07 | 0.92 | 0.70 |

| Remarriage | 1.06 | 0.96 | 1.08 | 0.97 | 0.99 | 1.12 | 1.16*** | 0.88*** | 0.71 |

| Children < 18 years | 1.02 | 0.95*** | 0.96 | 1.00 | 1.02 | 1.05 | 1.10*** | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Husband’s education | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.02 | 1.01 | 0.98 | 1.00 | 0.97 |

| Logged household income | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Public assistance | 1.05 | 0.97 | 1.02 | 0.99 | 0.92 | 1.01 | 1.06 | 1.11 | 1.23 |

| Wife full-time work | 0.83 | 1.03 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 1.04 | 0.96 | 0.94 | 1.01 | 0.90 |

| Wife extended hours | 1.43*** | 0.95 | 1.01 | 0.90 | 0.93 | 1.08 | 1.07 | 1.03 | 1.47*** |

| Husband’s job demands | 1.02 | 1.03 | 0.96 | 1.08 | 1.00 | 0.97 | 1.05 | 0.94 | 1.10 |

| Wife’s job demands | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 1.20*** | 0.96 | 1.09 | 1.05 | 1.02 | 0.94 |

| Husband employed | 0.86 | 1.01 | 1.09 | 0.93 | 1.00 | 1.09 | 0.86*** | 1.04 | 0.99 |

| Husband housework | 0.49 | 1.74*** | 1.01 | 1.07 | 1.23 | 0.52*** | 0.48*** | 0.82 | 0.16*** |

| Equal decision making | 0.99 | 1.08*** | 1.12*** | 0.96 | 0.97 | 1.05 | 0.89*** | 0.90*** | 1.00 |

| Religiosity | 0.77 | 0.95 | 1.13*** | 0.96 | 1.04 | 0.84 | 0.94 | 1.11*** | 0.93*** |

| Traditional gender | 1.17 | 1.02 | 1.09 | 1.03 | 0.97 | 1.02 | 1.00 | 0.93 | 0.70 |

| Lifelong marriage | 0.93 | 1.12 | 1.53*** | 0.80 | 0.95 | 1.20 | 0.63*** | 0.73*** | 1.02 |

| L2 (Npar) | 362.94 (23) | 2001.89 (23) | 1443.40 (23) | 679.68 (23) | 2393.15 (23) | 814.11 (23) | 905.02 (23) | 1282.96 (23) | 179.31 (23) |

| Bootstrap p value (SE) | 0.30 (0.02) | 0.28 (0.02) | 0.34 (0.02) | 0.34 (0.02) | 0.22 (0.02) | 0.33 (0.02) | 0.31 (0.02) | 0.34 (0.02) | 0.22 (0.02) |

| BIC | −14646.8661 | −13007.9161 | −13566.403 | −14330.1269 | −14830.4968 | −14195.699 | −14104.7849 | −13726.849 | −14830.4968 |

Note: BIC = Bayesian information criterion. Each column is a separate logistic regression model predicting membership in the group identified at the head of each column. Hhap, Mhap, and Lhap, respectively, stand for high, medium, and low marital happiness trajectories. Hcon, Mcon, and Leon, respectively, stand for high, medium, and low marital conflict trajectories.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Moving to the volatile marriages, we found that very little predicted membership in these marriages. We did find that spouses who cohabited and wherein wives had higher job demands had greater odds of membership in the middle happiness/high conflict group, whereas wives who worked extended hours had greater odds of membership in the high happiness/high conflict group. Overall, then, there was some evidence that wives’ work issues were associated with membership in volatile marriages.

The predictors of marital quality used in this study better predicted membership in avoider marriages. First, consistent with Gottman (1993) and Fitzpatrick (1988), we find that spouses in the high happiness/low conflict and middle happiness/low conflict groups had lower odds of divorcing in the future. Furthermore, spouses who were older at marriage and never experienced parental divorce had greater odds of being in the high happiness/low conflict group. Wives had lower odds of being in the middle happiness/low conflict group. Turning to the gender relations and attitude and values variables, we find that spouses with husbands who shared housework had lower odds of membership in the middle happiness/low conflict group. In contrast, spouses in marriages marked by equal decision making, more religious spouses, and spouses who believed in lifelong marriage had greater odds of membership in the high happiness/low conflict group. Overall, the pattern of results for the avoider marriages better supported the institutional model of marriage as husbands sharing in housework was negatively related and religiosity and traditional marriage attitudes were positively related to group membership in avoider marriages. Indeed, the institutional model argues that conflict should be lower and marital happiness higher in institutional marriages, consistent with these findings.

Turning now to the hostile-engaged and hostile-detached marriages, we found that spouses in hostile-engaged marriages, that is, in the low happiness/ high conflict and low happiness/middle conflict groups, as well as in hostile-detached marriages or the low happiness/low conflict group, had significantly greater odds of dissolving in the future. These results were again consistent with Gottman’s (1993) categorization of these marriages as unstable. Turning first to the hostile-engaged marriages, those spouses married more years and in a remarriage had greater odds of being in either the low happiness/high conflict or low happiness/middle conflict group. With regard to the other demographic variables, spouses with divorced parents and with more children less than the age of 18 years had greater odds of membership in the low happiness/high conflict group, whereas non-Whites and spouses who were married at older ages had greater odds of membership in the low happiness/ middle conflict group.

The gender relations variables were associated with membership in the hostile-engaged groups. Spouses in marriages in which husbands were unemployed, in which the husband did not help with housework, and in which decisions were not made equally had greater odds of membership in the low happiness/high conflict group. Only equal decision making predicted group membership in the low happiness/middle conflict group among the gender relations variables; spouses in marriages marked by equal decision making had lower odds of membership in the low happiness/middle conflict group. The attitude and values variables also predicted group membership into the hostile-engaged groups. Spouses who believed more in lifelong marriage had lower odds of membership in the low happiness/high conflict and the low happiness/middle conflict groups. More religious spouses had greater odds, however, of group membership in the low happiness/middle conflict group. Overall, membership in the hostile-engaged marriages was more common among spouses who were less egalitarian and less supportive of lifelong marriage. Thus, the results for the hostile-engaged groups partially supported both the institutional and companionate models of marriage.

The final hostile group was the hostile-detached group, or the low happiness/ low conflict group. Spouses married at older ages had greater odds of membership in this group, as did spouses in marriages in which wives worked extended hours. Overall, wives who worked extended hours were more likely to be in high conflict marriages. Spouses in marriages in which husbands did housework and spouses who were more religious had low odds of membership in the low happiness/low conflict group. Thus, again, the pattern of results appeared to support both the institutional and companionate models of marriage—religiosity, in this case, and equal decision making were both associated with a lower likelihood of being a member of the hostile-detached marriages.

Discussion

This article extends previous work on the marital life course by responding to three questions. First, we were able to find support for Gottman (1993) and Fitzpatrick’s (1988) typologies of married couples, using nationally representative data on married couples in 1980. Gottman suggests that marital conflict is relatively stable and that some couples have high levels of conflict whereas others have low levels. We found no single dominant pattern of change in marital conflict over time. Rather, we found three relatively stable marital conflict trajectory groups. Just less than a quarter of the sample was in a high marital conflict trajectory, about 60% was in a middle marital conflict trajectory, and about 17% was in a low marital conflict trajectory. The mean of marital conflict in the low conflict group was around two full standard deviations below the mean of marital conflict in the high conflict group over time, indicating that the differences in mean marital conflict between the trajectories were substantial. In contrast to VanLaningham et al.’s (2001) findings related to marital happiness and Umberson et al.’s (2006) findings with regard to negative interaction, we found little evidence of an increase in marital conflict over time.

Few predictors of marital quality were associated with trajectories of marital conflict. Consistent with the suppositions of the institutional model of marriage, strong belief in lifelong marriage predicted membership in the low marital conflict trajectories and was associated with lower odds of membership in the high marital conflict trajectory. In support of the companionate model, equal decision making was associated with greater odds of membership in the low marital conflict trajectory and lower odds of membership in the high marital conflict trajectory. Hence, a belief in lifelong marriage and marital cooperation in decision making were associated with marital conflict— the more cooperation and belief in the institution of marriage, the less conflict. These results were consistent with results found for marital happiness (Kamp Dush et al., 2008), that is, cooperation and a belief in the institution of marriage were associated with more marital happiness.

We crossed three marital happiness trajectories and our three marital conflict groups to identify the highest and lowest quality marriages and to replicate the marital typologies proposed by Gottman (1993) and Fitzpatrick (1988). A majority of couples were in validator marriages, the high happiness/ middle conflict and middle happiness/middle conflict groups. Validator marriages were less likely to dissolve, consistent with Gottman and Fitzpatrick’s typologies. They found validating couples avoided conflict unless there was a serious issue in the marriage. These couples were found to be good at communicating both their feelings and problems, as well as listening to and supporting their partner. Though we were unable to get at this level of detail in our data, the high happiness/middle conflict group was associated with more egalitarian behaviors, in support of the companionate model of marriage. We do find a higher proportion of our couples were in validator marriages, 54% compared with Gottman’s 19%. The difference could be related to our lack of detailed data on marital conflict behavior or differences in our sample and Gottman’s. Our sample was nationally representative of couples married in the year 1980. Gottman (see Gottman & Levenson, 1992, for a detailed description of his sample) gathered his sample in a two-stage procedure. First, 200 couples from Bloomington, Indiana, were recruited from newspaper advertisements, and they responded to a demographic questionnaire and two measures of marital satisfaction. From this sample, 85 couples were invited to participate in the lab assessments used in Gottman (1993). Couples were selected to be invited such that all parts of the distribution of marital satisfaction would be equally represented. Hence, our estimate is closer than Gottman to a population estimate of the proportion of validator couples in the United States, but it should be replicated in future research.

The next highest proportion of couples was represented in the volatile marriages. Again, somewhat consistent with Gottman (1993) and Fitzpatrick (1988), who both found that the volatile marriages were less likely to divorce, couples in the high happiness/high conflict and middle happiness/high conflict groups were no more likely to dissolve than they were to stay together. Volatile couples were described by Gottman and Fitzpatrick to value their independence more and to thrive on conflict. When they argued, volatile couples’ interactions were characterized by high levels of both negative and positive feelings. We did not find consistent predictors of membership in the high happiness/high conflict and middle happiness/high conflict groups in our data, but there was some evidence that wives with more demanding jobs had greater odds of group membership in the volatile trajectories.

Gottman (1993) and Fitzpatrick (1988) described avoider marriages as those spouses who minimized conflict and led separate lives with low levels of sharing. We found 6% of couples in high happiness/low conflict and middle happiness/low conflict groups or avoider marriages. Consistent with Gottman and Fitzpatrick, these marriages were less likely to dissolve. We found support for the institutional model of marriage in the avoider marriages’ models. Spouses in marriages with husbands who did less housework, more religious spouses, and spouses who believe in lifelong marriage were more likely to be in one of the two avoider marriages. Spouses in avoider marriages may circumvent conflict through altering their perceptions because they plan to be in their marriage for the long haul. However, spouses who reported more equal decision making, a hallmark of the companionate model of marriage, also had greater odds of being in the high happiness/low conflict group. This seemingly contradictory finding is consistent with Gottman’s (1993) finding that avoider couples emphasized “talking things out” but the emphasis was on finding “common ground rather than on differences” (p. 10) and differences were minimized and sometimes ignored. Ignoring differences may help bolster perceptions that the marriage is satisfying when in actuality there may be less companionship in this kind of marriage.

Building on Fitzpatrick (1988), Gottman (1993) identified two types of marriages that were more likely to dissolve. In our data, low happiness/high conflict and low happiness/middle conflict represented hostile-engaged couples. Consistent with Gottman, these groups had greater odds of dissolution. Hostile-engaged couples were characterized by Gottman as having more negative conflict and spouses often blamed and insulted each other with few positive behaviors. Though we were unable to get at this level of detail in data, we found some support for both the companionate and institutional models of marriage in the models of the hostile-engaged couples. Couples who were more egalitarian and couples who believed in lifelong marriage were less likely to be in the low happiness/high conflict and low happiness/middle conflict groups. Hostile-detached couples were described by Gottman as being emotionally uninvolved with one another for the most part, but when they did argue, the arguments were over trivial matters and were characterized by attacking and defensive behaviors. We identified the low happiness/low conflict couples as hostile-detached. The second shift (Hochschild, 1989) may have come into play in these couples—spouses were more likely to be in this group if the wife worked extended hours and the husband did less of the housework. These spouses were also less religious so they did not have an institutional foundation supporting their less companionate marriages, and hence it was not surprising that these marriages were more likely to dissolve.

Limitations

No study is without limitations. First, we used data from a representative sample of the marital population in 1980. A more contemporary cohort of married adults may yield different results, given the changes that have occurred in marriages, such as the increasing separateness of couples’ lives (Amato et al., 2007). We also relied on a single reporter. Future research should incorporate within and between couple models, examining whether married spouses report similar changes in marital conflict over time. We also used a single indicator of the frequency of conflict as our indicator of marital conflict. Future research should incorporate behavioral data, in particular, and scales of marital conflict to confirm these results. Attrition was also substantial in this sample. Though we used methods that allowed respondents to contribute until they dropped out and also conducted sensitivity analyses, selective attrition could have biased our estimates. A fourth limitation was that couples were already of varying marital durations in 1980. Those who survived marriage to be in the initial sample were more select because the most unhappy of spouses either did not make it into the sample or dropped from the sample early due to divorce, creating an upward bias in our estimates. Future research would benefit from repeated cross-section design. A final limitation was that predictor variables were measured after the respondent was married; therefore, our predictors were not exogenous. For example, a respondent’s degree of belief in lifelong marriage in 1980 was likely influenced by the quality of their marriage in 1980. The causal relationships between marital trajectories and predictors of marital quality are yet to be determined. Future research would benefit from premarital predictors of marital quality trajectories.

Conclusion

This article expands the scope of longitudinal marital research to include both marital happiness and conflict. VanLaningham et al.’s (2001) assertion was supported in that we found subgroups of individuals that did not follow the “dominate trajectory of decline” (p. 1336) in marital quality. We were able to identify Gottman (1993) and Fitzpatrick’s (1988) typologies of married couples as well as find support for both institutional and companionate models of marriage.

The most consistent pattern in the predictors of marital quality was that, overall, individuals who began the 20-year study period with an egalitarian marriage and were dedicated to the idea that marriage should last forever were more likely to stay at least somewhat happily married with average or little conflict. Wilcox and Nock (2006) argued for an institutional model of marriage, in which spouses who believe in the institution of marriage will have higher quality marriages because, first, they are involved in religious institutions that provide social support for marriage, and second, they will have a more altruistic mindset toward their marriage that will make them less likely to seek their own interests. Our work does support this model, particularly in the avoider marriages identified by Gottman (1993) and Fitzpatrick (1988). But our findings also support a companionate model of marriage (e.g., Amato et al., 2007) that argues that egalitarian marriages have higher marital quality. Shared decision making and husbands sharing in the burden of housework were associated with enduring high marital quality in the validator marriages, and a lack of egalitarian behaviors was associated with less stable, hostile marriages. A marriage marked by both institutional and companionate qualities would have the greatest likelihood of success in the long term according to our findings. The benefits of an egalitarian marriage and a belief in lifelong marriage may be underestimated in the marital literature, as the benefits may last across many years of the individual and marital life course.

Acknowledgment

We thank Frank D. Fincham, Scott M. Stanley, Elaine Wethington, and members of the Cornell Institute for the Social Sciences Evolving Family Theme Project for helpful comments on earlier drafts of this article.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article:

The Institute for the Social Sciences at Cornell University, the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grant 1K01HD056238 to Kamp Dush, and the National Institute on Aging Grants 5F32AG026926 and K992011 AG030471 to Taylor supported this research.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Amato PR, Booth A. Changes in gender role attitudes and perceived marital quality. American Sociological Review. 1995;60:58–66. [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR, Booth A, Johnson DR, Rogers SJ. Alone together: How marriage in America is changing. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR, DeBoer DD. The transmission of marital instability across generations: Relationship skills or commitment to marriage? Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63:1038–1051. [Google Scholar]

- Axinn WG, Barber JS. Living arrangements and family formation attitudes in early adulthood. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1997;59:595–611. [Google Scholar]

- Beach SRH, Fincham FD, Amir N, Leonard KE. The taxometrics of marriage: Is marital discord categorical? Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19:276–285. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.2.276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi SM, Robinson JP, Milkie MA. Changing rhythms of American family life. New York, NY: Russell Sage; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Booth A, Edwards JN. Starting over: Why remarriages are more unstable. Journal of Family Issues. 1992;13:179–194. doi: 10.1177/019251392013002004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth A, Johnson D, Amato P, Rogers S. Marital instability over the life course: A six-wave panel study, 1980, 1983, 1988, 1992–1994, 1997, 2000 (Version 1) [Data file] Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Clements ML, Stanley SM, Markman HJ. Before they said “I do”: Discriminating among marital outcomes over 13 years. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004;66:613–624. [Google Scholar]

- Cohan CL, Kleinbaum S. Toward a greater understanding of the cohabitation effect: Premarital cohabitation and marital communication. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64:180–192. [Google Scholar]

- Fincham FD, Beach SRH. Conflict in marriage: Implications for working with couples. Annual Review of Psychology. 1999;50:47–77. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.50.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick MA. Between husbands and wives: Communication in marriage. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Frisco ML, Williams KL. Perceived housework equity, marital happiness, and divorce in duel-earner households. Journal of Family Issues. 2003;24:51–73. [Google Scholar]

- Glenn ND. The course of marital success and failure in five American 10-year marriage cohorts. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1998;60:569–576. [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM. The roles of conflict engagement, escalation, and avoidance in marital interaction: A longitudinal view of five types of couples. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61:6–15. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM, Coan J, Carrere S, Swanson C. Predicting marital happiness and stability from newlywed interactions. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1998;60:5–22. [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM, Levenson RW. Marital processes predictive of later dissolution: Behavior physiology, and health. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;63:221–233. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.63.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton TB, Pratt EL. The effects of religious homogamy on marital satisfaction and stability. Journal of Family Issues. 1990;11:191–207. [Google Scholar]

- Heyman RE, Sayers SL, Bellack AS. Global marital satisfaction versus marital adjustment: An empirical comparison of three measures. Journal of Family Psychology. 1994;8:432–446. [Google Scholar]

- Hochschild A. The second shift: Working parents and the revolution at home. New York, NY: Viking Penguin; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Huston TL, Caughlin JP, Houts RM, Smith SE, George LJ. The connubial crucible: Newlywed years as predictors of marital delight, distress, and divorce. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;80:237–252. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.80.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DR, White LK, Edwards JN, Booth A. Dimensions of marital quality: Towards methodological and conceptual refinement. Journal of Family Issues. 1986;7:31–49. [Google Scholar]

- Jones BL, Nagin DS, Roeder K. A SAS procedure based on mixture models for estimating developmental trajectories. Sociological Methods & Research. 2001;29:374–393. [Google Scholar]

- Kamp Dush CM, Taylor MG, Kroeger RA. Marital happiness and psychological well-being across the life course. Family Relations. 2008;57:211–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2008.00495.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karney BR, Bradbury TN. The longitudinal course of marital quality and stability: Review of theory, method, and research. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;118:3–34. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.118.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Land KC. Introduction to the special issue on finite mixture models. Sociological Methods and Research. 2001;29:275–281. [Google Scholar]

- Locke H, Wallace K. Short marital adjustment and prediction tests: Their reliability and validity. Marriage and Family Living. 1959;21:251–255. [Google Scholar]

- Nagin DS. Analyzing developmental trajectories: A semiparametric, group based approach. Psychological Methods. 1999;4:139–157. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.6.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry-Jenkins M, Repetti RL, Crouter AC. Work and family in the 1990s. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000;62:981–998. [Google Scholar]

- Sher TG, Weiss RL. Negativity in marital communication: A misnomer? Behavioral Assessment. 1991;13:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Spanier GB. Measuring dyadic adjustment: New scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1976;38:15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Twenge JM, Campbell WK, Foster CA. Parenthood and marital satisfaction: A meta-analytic Review. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2003;65:574–583. [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D, Williams K, Powers DA, Liu H, Needham B. You make me sick: Marital quality and health over the life course. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2006;47:1–16. doi: 10.1177/002214650604700101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanLaningham J, Johnson DR, Amato PR. Marital happiness, marital duration, and the U-shaped curve: Evidence from a five-wave panel study. Social Forces. 2001;79:1313–1341. [Google Scholar]

- Vermut JK, Magidson J. Technical appendix for Latent Gold 3.0. 2004 Retrieved from http://www.statisticalinnovations.com/products/lg_app3.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Walster E, Walster GW, Berscheid E. Equity: Theory and research. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- White L, Rogers SJ. Economic circumstances and family outcomes: A review of the 1990s. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2000;62:1035–1051. [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox WB. Soft patriarchs, new men: How Christianity shapes fathers and husbands. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox WB, Nock SL. What’s love got to do with it? Equality, equity, commitment and women’s marital quality. Social Forces. 2006;84:1321–1345. [Google Scholar]

- Winship C, Radbill L. Sampling weights and regression analysis. Sociological Methods & Research. 1994;23:230–257. [Google Scholar]