Abstract

This study investigated relations between father involvement in caregiving and play and coparenting behavior using self-report and observational data from 80 two-parent families of preschool-aged children, and examined parents’ nontraditional beliefs about fathers’ roles and family earner status as moderators of these relations. Results indicated that greater father involvement in caregiving and play was associated with less observed undermining coparenting behavior in dual-earner families. Conversely, greater father involvement in caregiving was associated with less perceived supportive and greater perceived undermining coparenting behavior in single-earner families. Father involvement in play was not related to coparenting behavior among single-earner families. This study highlights the importance of considering parental employment patterns and the multidimensional nature of fathering behavior when studying fathering and coparenting.

It is increasingly understood that children’s social development in the family context is best conceptualized as a process in which all family members -- including mothers, fathers, siblings, and extended kin -- are considered to play important roles. Although there is a long research tradition focused on studying family influences on children’s development, only relatively recently have researchers broadened this effort beyond the study of mother-child or marital relationships to include a focus on other important aspects of the family system such as father involvement, or the degree to which fathers are involved in childrearing, and coparenting behavior, or the extent to which adults in the family support versus undermine each other’s parenting. Both father involvement and coparenting behavior have been linked empirically to children’s socioemotional functioning (Lamb, 1997; McHale et al., 2002).

However, investigations of father involvement and coparenting behavior have largely been pursued independently of each other. Thus, we know that parents who frequently support each other’s parenting and refrain from undermining each other’s parenting efforts foster healthy development in their children (e.g., Schoppe, Mangelsdorf, & Frosch, 2001), and that greater father involvement is associated with a variety of positive outcomes for children (e.g., Parke et al., 2002), but we have a more limited understanding of the interplay between these two important aspects of family life. The current study was designed to examine the potential impact of father involvement in caregiving and play, two important types of direct involvement that are aligned with more nontraditional and more traditional perspectives on paternal roles, respectively, on coparenting behavior in two-parent families. Given that relations between father involvement and coparenting behavior may depend upon other aspects of the family ecology (Doherty, Kouneski, & Erickson, 1998), particularly parents’ beliefs about fathers’ roles and family earner status (Lee & Doherty, 2007), we further examined these variables as moderators of the effects of father involvement on coparenting behavior.

Father Involvement

One aspect of the family system that has received increasing attention from researchers is fathers’ involvement in raising their children (Marsiglio, Amato, Day, & Lamb, 2000). This interest in fathers has emerged for several reasons, including changes that have taken place in the expected roles of fathers across many societies. Today’s fathers are increasingly expected to sharing parenting responsibilities more equally with mothers (Pleck & Pleck, 1997). However, although father involvement has shown modest increases over the last several decades, fathers continue to spend significantly less time than mothers caring for children (Hofferth, Pleck, Stueve, Bianchi, & Sayer, 2002; Pleck & Masciadrelli, 2004).

Such discrepancies between ideals and reality have fueled fathering research, especially as research evidence continues to support the benefits for children of involved fathering (Pleck & Masciadrelli, 2004). Children of highly involved fathers show greater cognitive competence and academic achievement (Flouri & Buchanan, 2004; McBride, Schoppe-Sullivan, & Ho, 2005), have higher self-esteem (Amato, 1994; Deutsch, Servis, & Payne, 2001), fewer behavior problems (Flouri & Buchanan, 2003; Mosley & Thomson, 1995), and greater social competence with peers and siblings (Parke et al., 2002; Volling & Belsky, 1992). Recent research suggests that the benefits of involved fathering typically persist even when controlling for maternal involvement (Marsiglio et al., 2000).

As research on fathering has proliferated, a perpetual concern is how father involvement should be defined. An influential model of father involvement was outlined by Lamb, Pleck, Charnov, and Levine (1987), who conceptualized three types of involvement: (a) accessibility (parent is physically and psychologically available to child), (b) interaction/engagement (parent participates with child in one-on-one activity), and (c) responsibility (parent assumes responsibility for care of child). Subsequent research supports the notion that father involvement is a multidimensional construct, likely encompassing both indirect forms of involvement such as financial providing and cognitive monitoring as well as direct forms that include caregiving and play (Hawkins & Palkovitz, 1999; Schoppe-Sullivan, McBride, & Ho, 2004). Not surprisingly, developmentally appropriate positive interaction/engagement (i.e., quality of father involvement) confers greater benefits to children than simple accessibility or responsibility (i.e., quantity of father involvement; Marsiglio et al., 2000; Pleck & Masciadrelli, 2004); however, multiple forms of involvement may lay the groundwork for the establishment of enduring father-child relationships (Lewis & Lamb, 2003).

Coparenting Behavior

In families characterized by multiple parents, one aspect of the family context within which father-child and other important relationships are nested is the coparenting relationship, or the relationship between adults in the family as parents. According to family systems theory (e.g., Minuchin, 1974), the coparenting relationship is a central element of family life, influencing parental adjustment, parenting, and child outcomes (Feinberg, 2003). Coparenting can be defined as joint parenting within a family context and reflects the extent to which parents do (or do not) cooperate as a team in raising their children (Feinberg). Coparenting behavior is exemplified by undermining (hostility, competition) and supportive (warmth, cooperation) elements of interaction (Belsky, Putnam, & Crnic, 1996).

Empirical research on coparenting in two-parent families is a relatively recent phenomenon, but the weight of the evidence already indicates the importance of coparenting behavior for children’s socioemotional functioning (McHale et al., 2002). Consistent links between undermining (hostile, competitive) coparenting behavior and children’s emotional and behavioral problems have been obtained (McHale & Rasmussen, 1998; Schoppe et al., 2001). In contrast, supportive coparenting relationships characterized by cohesion, cooperation and warmth show strong links to children’s prosocial behavior and social competence (McHale, Johnson, & Sinclair, 1999; Stright & Neitzel, 2003). Furthermore, several investigations have established that coparenting behavior exerts a unique influence on children’s adjustment, over and above the influence of both marital relationship quality (e.g., McHale & Rasmussen, 1998) and dyadic parenting quality (e.g., Belsky et al., 1996). These findings highlight that coparenting is not simply part of marital or parent-child dyadic relationships, but rather plays a distinct role in the family system (Margolin, Gordis, & John, 2001; Schoppe-Sullivan, Mangelsdorf, Frosch, & McHale, 2004).

Father Involvement and Coparenting Behavior: Does Equality Imply Harmony?

As research on coparenting has grown, questions have arisen about the connections between the father’s role in the family and the quality of the coparenting relationship. A central issue is whether parents need to share parenting tasks and responsibilities equally in order to achieve a successful coparenting relationship. Researchers who emphasize “equally shared parenting” (e.g., Deutsch, 2001) describe coparents as those couples who have made a commitment to parenting equality and have rejected more traditional gender roles dictating that mothers are better suited for caretaking than fathers. However, most coparenting researchers believe that couples do not need to share parenting equally in order to have a high-quality coparenting relationship. Instead, there are numerous ways that a couple can create family cohesion, consistency, predictability, rules, standards, and a safe and secure home environment (McHale et al., 2002), which do not necessarily involve parents sharing the same parenting styles or spending an equal amount of time with their children.

And yet, as mentioned above, our society has been increasingly calling upon its men to assume a more active role in raising their young children (Pleck & Pleck, 1997), and to some extent fathers’ involvement has increased accordingly (Pleck & Mascidrelli, 2004). One might wonder: What is the impact of having two (rather than one) involved parents on the coparenting relationship? However, the lack of empirical data focusing on the connections between father involvement and coparenting has left this question unanswered. On the one hand, it seems obvious that greater father involvement may foster more supportive coparenting behavior (e.g., father steps in to help and support mother and she is pleased). Although little research has addressed this issue directly, a number of studies have demonstrated relations between greater father involvement and higher marital relationship quality (e.g., Blair, Wenk, & Hardesty, 1994; Lee & Doherty, 2007).

However, it is also important to consider the converse: that greater father involvement may lead to more disagreements between parents surrounding parenting issues. Such disagreements (e.g., father finally asserts his opinion about a particular parenting practice and disagrees with mother) could potentially increase the amount of undermining coparenting behavior. Providing support for this possibility, negative associations between father involvement and marital quality have also been found (e.g., Crouter, Perry-Jenkins, Huston, & McHale, 1987; Nangle, Kelley, Fals-Stewart, & Levant, 2003). In addition, the limited literature on “maternal gatekeeping” suggests that not all mothers may desire or facilitate father involvement (e.g., Allen & Hawkins, 1999; Schoppe-Sullivan, Brown, Cannon, Mangelsdorf, & Sokolowski, 2008). Thus, at least in some cases, successful coparenting may result from low levels of father involvement. Given these divergent possibilities, a particularly fruitful direction for research may be to explore factors that moderate relations between father involvement and coparenting behavior.

The “parental beliefs” model

One factor that may be particularly important to consider when examining associations between father involvement and coparenting behavior is parents’ beliefs about appropriate parent and gender roles. Empirical evidence supports the notion that both mothers’ and fathers’ beliefs about fathers’ roles are key correlates of paternal involvement (e.g., Beitel & Parke, 1998; Nangle et al., 2003), such that fathers tend to be more involved in childrearing when they and their partners hold more nontraditional beliefs. Clearly, though, not all parents hold such beliefs. Hackel and Ruble (1992) found that women who endorsed more egalitarian gender roles were most dissatisfied when men participated less in childcare than they had expected, whereas women who endorsed more traditional gender roles were most dissatisfied when their partners participated more in childcare then they had expected. Thus, depending on parents’ beliefs and expectations, adaptive coparenting behavior may be facilitated by higher or lower levels of father involvement. Consistent with this notion, Lee and Doherty (2007) found that fathers’ attitudes toward father involvement moderated the relation between father involvement and marital satisfaction, such that a positive association between involvement and marital satisfaction was observed only for fathers with positive attitudes toward father involvement.

The “family earner status” model

Another aspect of the family ecology that may affect relations between father involvement and coparenting is parental employment patterns, which figure significantly in Doherty et al.’s (1998) theoretical model of responsible fathering. In fact, research suggests that family earner status (dual- vs. single-earner) may moderate the relation between father involvement and marital satisfaction. In their recent study, Lee and Doherty (2007) found that the relation between father involvement and marital satisfaction was positive in dual-earner families, but negative in single-earner families. In contrast, three older studies found a negative association between father involvement and marital satisfaction for dual-earner, but not single-earner families (Crouter et al., 1987; Grych & Clark, 1999; Volling & Belsky, 1991), and two of those studies found a positive association between father involvement and marital satisfaction for single-earner families (Grych & Clark; Volling & Belsky).

Type of father involvement

In attempting to understand and test the parents’ beliefs and family earner status models, it is critically important to take the type of father involvement into account. In the present study, we measured two important aspects of father involvement – involvement in caregiving activities and involvement in play activities. Direct father involvement in caregiving involves the father’s participation in more typically “maternal” activities such as preparing meals for the child and getting up with the child when s/he wakes up at night. This type of involvement is more consistent with the modern ideal of father as “co-parent” (Pleck & Pleck, 1997) and may be desirable for more nontraditional parents, whose views about fathers are more consistent with this type of involvement, or those in dual-earner families, whose schedules frankly demand greater sharing of child care labor. In contrast, father involvement in caregiving may not be desirable for parents with less nontraditional beliefs about fathers’ roles, or those in single-earner families in which mothers are at home with their children and expected to take on the bulk of the child care activities. In fact, in these families, greater father involvement in caregiving may result in friction between parents, consistent with the maternal gatekeeping hypothesis (e.g., Allen & Hawkins, 1999; Schoppe-Sullivan et al., 2008).

Father involvement in play includes activities encompassing physical play and play with toys (e.g., building sets, balls). This type of father involvement is consistent with the more traditional ideal of the father as a “Dad” - a father who engages in fun leisure-time activities with his children (Pleck & Pleck, 1997). The role of the father as a playmate continues to receive emphasis in recent research (Paquette, 2004; Roggman, Boyce, Cook, Christiansen, & Jones, 2004). According to the parents’ beliefs model, because father involvement in play may be consistent with more traditional views of fathers’ roles, greater father involvement in play should be associated with more adaptive coparenting behavior in families with parents who espouse less nontraditional beliefs. For parents with more nontraditional beliefs, father involvement in play should have neither positive nor negative implications for coparenting, because for these parents, father involvement in caregiving activities has augmented – but not supplanted – father involvement in play activities.

The implications of the family earner status model with respect to relations between father involvement in play and coparenting behavior are somewhat different. From this perspective, greater father involvement in play as well as caregiving should be beneficial for coparenting in dual-earner families, because the division of all aspects of parenting needs to be shared, just as the role of economic provider is also shared. For single-earner families, though, according to the family earner status model, greater father involvement in play activities should not have positive or negative implications for coparenting, because it is neither necessary for effective coparenting nor does it encroach upon the mother’s role as primary caregiver.

The Present Study

Given the demonstrated importance of both father involvement and coparenting behavior for children’s development, and the potential for quite disparate patterns linking father involvement and coparenting behavior, it is surprising that little research has examined the connections between these aspects of the family system. The resulting gaps in knowledge underscore the importance of the current investigation, which was guided by two questions: (1) What are the relations between father involvement in caregiving and play and coparenting behavior? (2) Do parents’ nontraditional beliefs about the roles of fathers and family earner status moderate associations between father involvement and coparenting behavior? Rather than anticipating straightforward links between father involvement and coparenting behavior, we expected that the associations would differ based on parents’ nontraditional beliefs and family earner status, and that the type of father involvement (caregiving versus play) would matter as well.

Specifically, with respect to question two, we tested the appropriateness of the parental beliefs model versus the family earner status model. Recall that the hypotheses generated by the parental beliefs model include the following: (a) greater father involvement in caregiving should predict greater supportive and less undermining coparenting behavior for parents with more nontraditional beliefs about fathers, but the opposite should be true for parents with less nontraditional beliefs; and (b) greater father involvement in play should only matter for coparenting in families where parents have less nontraditional beliefs about fathers, and in those families greater play by fathers should predict higher levels of supportive and lower levels of undermining coparenting behavior. In contrast, the hypotheses stemming from the family earner status model are: (a) greater father involvement in caregiving and play will be associated with greater supportive and less undermining coparenting behavior in dual-earner families; and (b) greater father involvement in caregiving should be related to lower levels of supportive and higher levels of undermining coparenting in single-earner families, but greater father involvement in play should not matter for such families.

Method

Participants

Eighty families participated in this study as part of a larger research project focusing on family relationships and children’s development. Participating families included a mother, father, and a preschool-aged child. Families with multiple children were allowed to participate in the study. However, only one preschool-aged child per family was included in the study. Families were recruited through local preschools, churches, a newspaper ad, and by word-of-mouth. At the time of participation, children were approximately 4.1 years old (SD = .5 years; 41 boys, 39 girls). Mothers’ ages ranged from 22.2 to 56.2 years with a mean age of 36.1 years (SD = 5.4 years). Fathers’ ages ranged from 25.1 to 56.7 years with a mean age of 38.1 years (SD = 6.0 years).1 Annual family income ranged from less than $10,000 to over $100,000 (Mdn = $71,000 to 80,000). Sixty-six mothers and 64 fathers had obtained at least a college degree (range: high school degree to Ph.D.). Sixty-one children who participated were European American, seven were African American, one was Asian, 10 were of mixed race/ethnicity, and race/ethnicity for one child was not reported. Sixty-seven of the participating mothers were European American, eight were African American, two were Asian, two were of mixed race/ethnicity, and race/ethnicity for one mother was not reported. Sixty-five of the participating fathers were European American, seven were African American, three were Hispanic, one was Asian, one was of mixed race/ethnicity, and three fathers did not indicate their race/ethnicity. All couples were married or cohabiting for an average of 9.2 years (SD = 4.5 years). Thirteen of the participating families had only one child, 46 families had two children, 14 families had three children, three families had four children, three families had 5 children, and only one family had six or more children. Fifty of the participating children were first-born children, 17 were second-born children, 10 were third-born children, one was fourth-born, one was fifth-born, and one was sixth or later-born.

Data Collection

First, mothers and fathers were mailed identical packets of questionnaires to complete at home. The questionnaires assessed parents’ demographic information and tapped their perceptions of father involvement and coparenting relationships in their families. Parents were instructed to complete their questionnaires independently and to bring them to the laboratory visit. Two weeks after receiving the questionnaire packets, the families visited the laboratory for 1.5 hours. At the visit, both parents and their child completed two 10-minute videotaped tasks together. The first task required the mother, father and child to draw a picture of their whole family together, and after completing the picture, to label the family members that had been drawn. The second task required families to build a house together out of a toy building set. For participating in this study, families received a $30 gift card to a local store. This study was approved by and conducted under the oversight of the University’s Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Father involvement in caregiving and play

Fathers reported on the frequency of their involvement in developmentally appropriate activities with their children using items derived from measures of father involvement used in large national surveys (e.g., the PSID-CDS, see Schoppe-Sullivan, McBride, et al., 2004; the DADS initiative, see Cabrera et al., 2004). Seven items each assessed paternal involvement in caregiving activities (e.g., prepare meals for your child) and play activities (e.g., play together with toys for building things). Each item was rated on a 6-point scale (1 = not at all to 6 = more than once a day). Items reflecting father involvement in caregiving and play were averaged to create summary scores (αs = .72 and .76, respectively).

Observations of coparenting behavior

Coparenting behavior was coded from the videotaped family interaction episodes by a team of two trained researchers. The coders used scales developed by Cowan and Cowan (1996) to rate the overall quality of coparenting incidents within the taped interactions. These scales have been used and validated in previous investigations (Schoppe et al., 2001; Schoppe-Sullivan, Mangelsdorf, et al., 2004). The seven dimensions that the interactions were rated for, which tap important aspects of supportive and undermining coparenting behavior, are: pleasure (degree to which parents seem to enjoy coparenting), warmth (how affectionate and emotionally supportive the partners are of each other), cooperation (extent to which partners help and support one another instrumentally in coparenting), interactiveness (the extent to which parents engage with each other verbally and nonverbally), displeasure (degree to which parents do not enjoy working together or coparenting), anger (extent to which partners show hostility or irritation with each other), and competition (degree to which parents try to “outdo” each other in their efforts to work successfully with the child). These qualities were rated using the following scale: 1 = very low (the behavior is infrequent) to 5 = very high (the behavior happens numerous times). It is important to note that these coparenting behaviors only reflect how the parents interact together regarding parenting-related issues (i.e., the behaviors coded do not include behaviors directed from one parent to the child). Each family received two sets of ratings – one set for the drawing task and one for the building task. These ratings were averaged to create one score for each family on each scale across the 20 minutes of interaction.

Each of the trained raters was randomly assigned half of the drawing episodes and half of the building episodes, and the same rater did not code a family in both episodes with the exception of randomly selected episodes that the coders both rated to ensure consistency. For the 29% of episodes that the coders both rated, gamma coefficients were used to assess interrater reliability, because they are statistics that control for chance agreement like kappa but are more appropriate for ordinal data (Hays, 1981; Liebetrau, 1983). Gammas for the coparenting coding were appropriate, ranging from .78 – .94 (M = .88). The coding data were reduced based on the principal components analysis conducted for a previous report (for details see Schoppe-Sullivan, Weldon, Cook, Davis, & Buckley, 2009). This analysis yielded two components. Component 1, which was named Observed Supportive Coparenting, was characterized by high loadings for pleasure, warmth, cooperation, and interactiveness. Component 2, which was named Observed Undermining Coparenting, was characterized by high loadings for displeasure, anger, and competition. On the basis of these results, two composite variables representing observed supportive and undermining coparenting, respectively, were created by averaging scores for pleasure, warmth, cooperation, and interactiveness, and by averaging scores for displeasure, anger, and competition.

Perceptions of coparenting behavior

Mothers and fathers each responded to fourteen items designed to assess their perceptions of their partner’s coparenting behavior using the Perceptions of Coparenting Partners questionnaire (PCPQ; Stright & Bales, 2003). Half of the items reflect supportive coparenting behaviors (e.g., “My spouse backs me up when I discipline my child”), and the other half reflect undermining coparenting behaviors (e.g., “My partner competes with me for my child’s attention”). Each parent rated the frequency of their partner’s behaviors on a scale from 1 = never to 5 = always. Although mothers’ and fathers’ perceptions of supportive (r = .22, p = .06) and undermining (r = .21, p = .07) coparenting behavior were only modestly correlated, summary scores for perceived supportive coparenting and perceived undermining coparenting were created by averaging mothers’ and fathers’ responses to the support items and the undermining items (separately). This decision allowed the creation of variables parallel to those derived from the observations of coparenting behavior, and is supported by the acceptable Cronbach’s alphas for perceived supportive coparenting (.77) and perceived undermining coparenting (.70).

Nontraditional beliefs about fathers’ roles

To assess mothers’ and fathers’ attitudes about the roles of fathers in the family, each parent completed the What is a Father? Questionnaire (WIAF; Schoppe, 2001). The WIAF questionnaire is a 15-item measure adapted from Palkovitz’s (1984) Role of the Father Questionnaire. Items on the WIAF ask respondents to rate statements concerning fathers and fathering from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. The WIAF includes items that tap both more nontraditional and more traditional beliefs about fathers’ roles (e.g., “fathers and mothers should spend an equal amount of time with their children”; “fathers should be the disciplinarians in the family”). For the purposes of this study we focused on parents’ ratings of four nontraditional attitudes statements which represent the modern ideal of the father as an equally capable and involved coparent. For example, one item on the nontraditional attitudes scale is: “Fathers are just as sensitive in caring for children as mothers are.” Parents’ ratings on these four items were averaged to yield a summary score, with higher scores indicating more nontraditional beliefs about fathers’ roles. Cronbach’s alphas for this scale were .69 for mothers and .75 for fathers. Parents’ nontraditional beliefs about the roles of fathers were significantly correlated, r = .25, p < .05, and were averaged together to create a family-level beliefs variable for use in subsequent analyses.

Family earner status

Half of the study families (n = 40) were single-earner families in which the father worked outside the home (> 20 hours per week) but the mother did not. The other half of the participating families were dual-earner families (n = 40). In these families, both parents worked outside the home for greater than 20 hours per week.

Analysis Procedure

First, preliminary analyses were conducted to examine relations among the independent variables (fathers’ caregiving, fathers’ play, parents’ nontraditional beliefs about fathers, family earner status) as well as relations between the independent and dependent (observed and perceived supportive and undermining coparenting behavior) variables.

Subsequently, hierarchical regression analyses were used to examine the individual and interactive contributions of fathers’ caregiving and play, parents’ nontraditional beliefs about fathers’ roles, and family earner status to observers’ and parents’ perceptions of coparenting behavior. Two series of equations were computed, one considering the contributions of fathers’ caregiving to coparenting behavior, and one considering the contributions of fathers’ play. Further, each series consisted of four hierarchical regressions, each predicting one of the dependent variables (observed supportive coparenting, observed undermining coparenting, perceived supportive coparenting, perceived undermining coparenting). Thus, a total of eight hierarchical regressions were conducted.

On the first step, family income was entered as a control variable.2 On the second step the following variables were entered as a block: fathers’ caregiving (or play), parents’ nontraditional beliefs about fathers’ roles, and family earner status. On the third step, we entered the two-way interaction between fathers’ caregiving (or play) and parents’ nontraditional beliefs, and on the fourth and final step we entered the two-way interaction between fathers’ caregiving (or play) and family earner status. We entered the two-way interaction effects on separate steps in order to gauge their unique contributions to coparenting behavior, and entered the interactions with parents’ nontraditional beliefs first given the somewhat stronger theoretical and empirical basis for expecting parents’ beliefs to play a consistent moderating role.

Given that each equation already included six predictors for a sample size of N = 80 (at the limit of most “rules of thumb” regarding subjects-to-variables ratios; see Green, 1991), the contributions of fathers’ caregiving and play were considered in separate sets of regression analyses. Before the regressions were conducted, all key independent variables were mean-centered, except for family earner status, which was dummy coded (0 = single-earner; 1 = dual-earner). If a significant interaction was obtained, a graph of the interaction was created by substituting particular values into the regression equation (i.e., plus and minus one standard deviation from the mean for the father involvement and parents’ beliefs variables and 0 or 1 for the earner status variable). Interpretation of significant interaction effects was further enhanced through simple slopes analysis (Aiken & West, 1991; Preacher, Curran, & Bauer, 2006).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Descriptive statistics and intercorrelations for all study variables are presented in Table 1. When parents had more nontraditional beliefs about fathers, fathers were more involved in caregiving, r = .29, p < .05, but not in play, even as fathers’ involvement in caregiving and play was significantly correlated, r = .28, p < .05. Parents’ and observers’ perceptions of supportive and undermining coparenting behavior showed modest convergence (r = .24, p < .05 for both associations). There were no significant correlations between father involvement in caregiving and play and any of the measures of coparenting behavior.

Table 1.

Intercorrelations and Descriptive Statistics for Father Involvement and Coparenting Behavior Variables

| Intercorrelations | Overall | Single-Earners | Dual-Earners | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | M | SD | Range | M | SD | Range | M | SD | Range |

| 1. Fathers’ Caregiving | 1.00 | 3.8 | .6 | 2.7 –5.3 | 3.8 | .5 | 3.0 – 5.3 | 3.9 | .6 | 2.7 – 5.0 | ||||||

| 2. Fathers’ Play | .28* | 1.00 | 3.8 | .7 | 2.1 –5.4 | 3.7 | .7 | 2.1 – 5.3 | 3.8 | .8 | 2.4 – 5.4 | |||||

| 3. Nontraditional Beliefs | .29* | .12 | 1.00 | 4.1 | .6 | 2.6 –5.0 | 3.8a | .6 | 2.6 – 4.8 | 4.3a | .4 | 3.1 – 5.0 | ||||

| 4. Supportive Coparenting (O) | −.01 | .11 | .07 | 1.00 | 2.8 | .4 | 1.8 –3.8 | 2.7 | .4 | 1.8 – 3.4 | 2.8 | .4 | 2.0 – 3.8 | |||

| 5. Undermining Coparenting (O) | −.06 | −.22 | .06 | −.34** | 1.00 | 1.8 | .5 | 1.0 –3.2 | 1.9 | .5 | 1.0 – 3.0 | 1.8 | .5 | 1.1 – 3.2 | ||

| 6. Supportive Coparenting (P) | −.13 | .01 | .05 | .24* | −.09 | 1.00 | 4.2 | .3 | 3.5 –5.0 | 4.2 | .4 | 3.5 – 5.0 | 4.2 | .3 | 3.5 – 4.9 | |

| 7. Undermining Coparenting (P) | .09 | −.01 | .01 | −.24* | .24* | −.71** | 1.00 | 1.6 | .3 | 1.0 –2.4 | 1.6 | .3 | 1.0 – 2.2 | 1.6 | .4 | 1.1 – 2.4 |

Note. Corresponding subscripted letters indicate mean-level differences significant at p < .01.

O = Observed Coparenting Behavior; P = Parents’ Perceptions of Coparenting Behavior.

p < .05

p < .01.

One significant difference between single and dual-earner families emerged with respect to the central variables considered in this study: parents from dual-earner families were found to have more nontraditional beliefs about the roles of fathers than parents from single-earner families, t(77) = −4.05, p < .01. We also tested for significant differences between dual-earner and single-earner families with respect to family income, given that two sources of income are likely to yield higher earnings than a single source. Indeed, in the current sample, dual-earner families had higher family incomes (Mdn = 91,000–100,000) than single-earner families (Mdn = 71,000–80,000; Somers’ d = .38, p < .01).

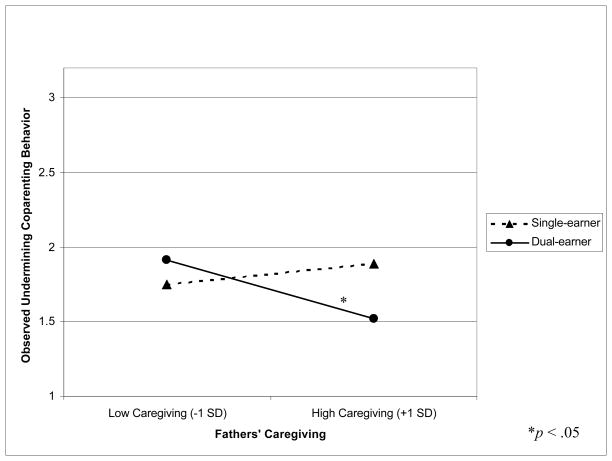

Equations considering fathers’ involvement in caregiving

When considering fathers’ involvement in caregiving as a predictor of observed supportive coparenting, none of the sets of variables entered on the four steps resulted in significant F-change. However, when predicting observed undermining coparenting, the addition of the two-way interaction between fathers’ caregiving and family earner status on the fourth step resulted in significant model improvement, β = −.41, p < .05, ΔR2adj = .04, F-change = 4.13 (see Table 2). As shown in Figure 1, a simple slopes analysis revealed that there was no significant relation between fathers’ involvement in caregiving and observed undermining coparenting behavior in single-earner families, simple slope = .12, p = .45. However, the slope for the line representing dual-earner parents was significantly different from zero, simple slope = −.34, p < .05. Thus, greater caregiving by fathers in dual-earner families, but not single-earner families, was associated with lower levels of observed undermining coparenting.

Table 2.

Hierarchical Regressions of Observed and Perceived Coparenting Behavior on Fathers’ Caregiving, Parents’ Nontraditional Beliefs, and Family Earner Status

| Observed Supportive Coparenting | Observed Undermining Coparenting | Perceived Supportive Coparenting | Perceived Undermining Coparenting | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | ΔR2adj | ΔF | β | ΔR2adj | ΔF | β | ΔR2adj | ΔF | β | ΔR2adj | ΔF | |

| Predictors | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Step 1 | −.01 | .01 | −.01 | .01 | −.01 | .32 | −.01 | .20 | ||||

| Family Income | .01 | .01 | −.07 | .05 | ||||||||

| Step 2 | −.01 | .80 | −.02 | .51 | −.01 | .71 | −.02 | .49 | ||||

| Fathers’ Caregiving (FC) | −.02 | −.10 | −.15 | .09 | ||||||||

| Nontraditional Beliefs (NB) | .02 | .13 | .13 | −.08 | ||||||||

| Family Earner Status (ES) | .18 | −.12 | −.09 | .14 | ||||||||

| Step 3 | −.01 | .66 | −.01 | .34 | −.01 | .16 | −.01 | .58 | ||||

| FC X NB | −.11 | .08 | .05 | .10 | ||||||||

| Step 4 | .01 | 1.18 | .04* | 4.13* | .05* | 4.97* | .05* | 4.44* | ||||

| FC X ES | .22 | −.41* | .45* | −.43* | ||||||||

Note.

p < .05

p < .01.

Figure 1.

Family earner status moderates relations between fathers’ caregiving and observed undermining coparenting behavior.

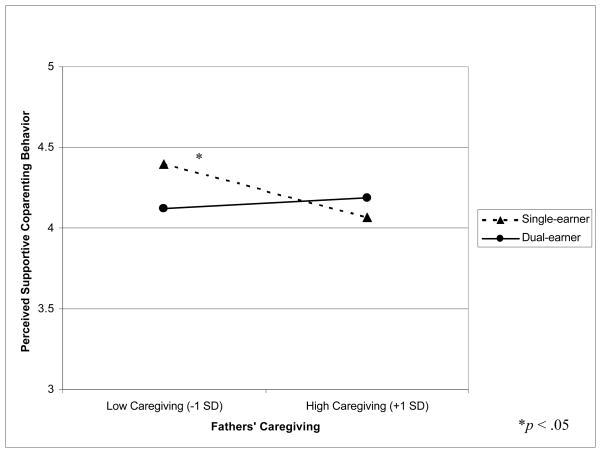

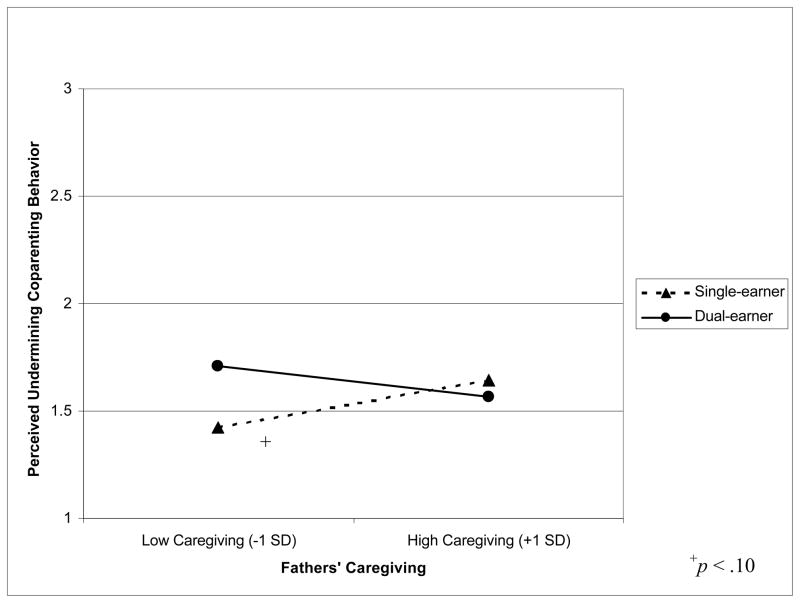

When predicting perceived supportive coparenting from fathers’ caregiving, parents’ nontraditional beliefs, family earner status, and their interactions, the addition of the Fathers’ Caregiving X Family Earner Status interaction on Step 4 resulted in significant model improvement, β = .45, p < .05, ΔR2adj = .05, F-change = 4.97 (see Table 2). The significant interaction is depicted in Figure 2. A simple slopes analysis showed that the association between fathers’ caregiving and perceived supportive coparenting behavior was significant for single-earner families, simple slope = −.29, p < .05, but not for dual-earner families, simple slope = .06, p = .59. In other words, greater caregiving by fathers was associated with lower perceived support by parents – but only in single-earner families. An analogous interaction effect was found in the equation predicting perceived undermining coparenting behavior. The Fathers’ Caregiving X Family Earner Status interaction again resulted in significant model improvement, β = −.43, p < .05, ΔR2adj = .05, F-change = 4.44 (see Table 2). As depicted in Figure 3, the slope of the line for single-earner families approached significance, simple slope = .19, p = .08, whereas the slope of the line for dual-earner families did not, simple slope = −.13, p = .24. Thus, higher involvement in caregiving by fathers was related to higher levels of undermining coparenting behavior from the parents’ perspective – but only for single-earner families.

Figure 2.

Family earner status moderates relations between fathers’ caregiving and perceived supportive coparenting behavior.

Figure 3.

Family earner status moderates relations between fathers’ caregiving and perceived undermining coparenting behavior.

Equations considering fathers’ involvement in play

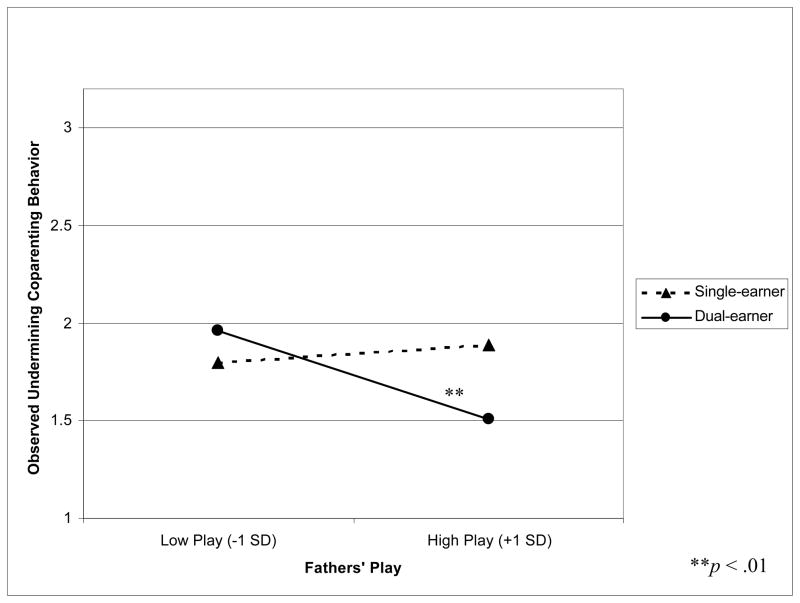

When considering fathers’ involvement in play instead of caregiving in the second series of regression analyses, a quite different pattern emerged. None of the sets of variables entered on any of the steps accounted for significant variance in observed supportive coparenting behavior. However, when regressing observed undermining coparenting on the set of predictor variables, the Fathers’ Play X Family Earner Status interaction entered on Step 4 resulted in significant improvement to the model, β = −.42, p < .05, ΔR2adj = .06, F-change = 5.36 (see Table 3). A graph representing this interaction effect is shown in Figure 4. For single-earner families, the relation between fathers’ involvement in play and observed undermining coparenting was not significant, simple slope = .06, p = .61. In contrast, for dual-earner families, greater father involvement in play was associated with less observed undermining coparenting behavior, simple slope = −.32, p < .01.

Table 3.

Hierarchical Regressions of Observed and Perceived Coparenting Behavior on Fathers’ Play, Parents’ Nontraditional Beliefs, and Family Earner Status

| Observed Supportive Coparenting | Observed Undermining Coparenting | Perceived Supportive Coparenting | Perceived Undermining Coparenting | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | ΔR2adj | ΔF | β | ΔR2adj | ΔF | β | ΔR2adj | ΔF | β | ΔR2adj | ΔF | |

| Predictors | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Step 1 | −.01 | .01 | −.01 | .01 | −.01 | .32 | .05 | −.01 | .20 | |||

| Family Income | .01 | .01 | −.07 | |||||||||

| Step 2 | .00 | 1.03 | .02 | 1.64 | −.03 | .18 | −.03 | .34 | ||||

| Fathers’ Play (FP) | .10 | −.23* | .01 | −.03 | ||||||||

| Nontraditional Beliefs (NB) | .00 | .12 | .08 | −.05 | ||||||||

| Family Earner Status (ES) | .18 | −.10 | −.08 | .13 | ||||||||

| Step 3 | −.01 | .75 | −.01 | .00 | .00 | 1.00 | .01 | 1.71 | ||||

| FP X NB | −.10 | .01 | −.12 | .15 | ||||||||

| Step 4 | −.01 | .18 | .06* | 5.36* | .04 | 3.76 | .03 | 2.76 | ||||

| FP X ES | .08 | −.42* | .36 | −.31 | ||||||||

Note.

p < .05

p < .01.

Figure 4.

Family earner status moderates relations between fathers’ play and observed undermining coparenting behavior.

Finally, when predicting parents’ perceptions of supportive and undermining coparenting behavior from fathers’ play, parents’ nontraditional beliefs about fathers, family earner status, and their interactions, none of the steps resulted in significant improvement to the models, nor did any of the variables entered on Steps 1–4 explain significant variance.

Discussion

Our findings highlight the intricate nature of relations between father involvement and coparenting behavior, which depended upon parental employment patterns, the type of father involvement examined, and whether coparenting behavior was measured from the perspectives of observers or parents. The complex picture that emerged from our findings accentuates the need for researchers to consider aspects of the family ecology, as well as the multidimensional nature of fathering behavior, when studying fathering and coparenting and when making recommendations to fathers and families regarding the best ways to foster the high-functioning family relationships that play a critical role in children’s positive development.

Our findings were most consistent with the family earner status model, which posits that relations between father involvement and coparenting behavior depend primarily upon patterns of employment within the family. Recall that the family earner status model specified two hypotheses. First, greater father involvement in caregiving and play was anticipated to relate to greater supportive and less undermining coparenting behavior in dual-earner families. Indeed, we found that when fathers in dual-earner families were more involved in caregiving and play activities with their children, their coparenting behavior was rated as more adaptive; in particular, lower levels of undermining coparenting behavior were observed. Second, according to the family earner status model, greater father involvement in caregiving was expected to relate to lower levels of supportive and higher levels of undermining coparenting in single-earner families, but greater father involvement in play was not expected to matter for such families. This hypothesis was also supported by our findings. As predicted, we found that coparenting behavior suffered when fathers in single-earner families were more involved in caregiving. More specifically, parents reported less supportive and more undermining coparenting behavior when fathers in single-earner families were more involved in caregiving. In contrast, fathers’ involvement in play was not related to observed or perceived coparenting behavior among single-earner families.

That the links we found between father involvement and coparenting behavior depended upon parental employment patterns is consistent with Lee and Doherty’s (2007) finding that the relation between father involvement and marital satisfaction was dependent upon family earner status. Specifically, they found that father involvement and marital satisfaction were positively associated in dual-earner families, but negatively associated in single-earner families. However, our findings and those of Lee and Doherty reflect the opposite pattern of those reported in several older studies (i.e., Crouter et al., 1987; Grych & Clark, 1999; Volling & Belsky, 1991). We suspect that this divergence is rooted in the fact that several decades have passed since the data from the earlier studies were collected. In the time that has passed, dual-earner families have become much more normative and single-earner families less so (U. S. Census Bureau, 2006). Clearly an important consideration for research on parenting and family relationships is the broader social and historical context in which families are embedded. However, it also seems prudent to re-emphasize that although we have highlighted parallels between the coparenting and marital literatures, coparenting relationship quality is not synonymous with marital quality, dyadic adjustment, or relationship satisfaction (Schoppe-Sullivan, Mangelsdorf, et al., 2004). Thus, future research would do well to consider relations between multiple aspects of interparental relationship quality and diverse types and levels of father involvement.

It is interesting to note that the relations between father involvement and coparenting behavior, and the moderating role of family earner status, differed when considering observed coparenting behavior versus parents’ perceptions of coparenting behavior. In other words, even though dual-earner parents showed more adaptive coparenting behavior when fathers were more involved in caregiving and play, they did not necessarily view their coparenting relationship more positively. In turn, when fathers in single-earner families were more involved in caregiving, parents perceived their coparenting behavior as less adaptive, but the same pattern was not apparent in the observations of coparenting behavior. There are several possible reasons for this discrepancy. One possibility involves the fact that these data were all obtained concurrently, and thus, the passage of time may be necessary before effects of father involvement and coparenting behavior are reflected in parents’ perceptions. Alternatively, the types of coparenting behaviors coded by observers may inherently advantage families in which both parents are highly involved in the day-to-day work of childrearing. This interesting pattern of findings underscores the need to assess coparenting behavior using multiple measures, as others have emphasized (McHale & Rotman, 2007).

It is also important to examine the somewhat surprising fact that – in contrast to previous relevant studies (e.g., Hackel & Ruble, 1992; Lee & Doherty, 2007) - we did not find much support for the parental beliefs model. There are several potential explanations. First, it is possible that our measure of parents’ nontraditional beliefs about fathers was not sensitive enough to tap the kinds of attitude differences that may affect relations between father involvement and coparenting behavior. It may also be fruitful for future research to consider disagreement between parents regarding beliefs about fathers’ roles, as it is easy to imagine that parents with different beliefs may be more likely to experience coparenting struggles. However, recall that our family-level measure of parents’ nontraditional beliefs was related to family earner status. Perhaps family earner status is in some sense a “better” measure of parents’ beliefs because it captures how parents put their more general or ideal beliefs into practice in family life. In future work, more nuanced measures of parental beliefs, including both ideal and more pragmatic dimensions, may help disentangle these possibilities. It is also probable that parents’ beliefs affect their employment patterns, which in turn affect relations between fathering and coparenting. However, even though family earner status and parents’ nontraditional beliefs were related, they did not behave the same way in our study, and the pattern of our results was, in fact, inconsistent with the parental beliefs model. According to the beliefs model, greater father involvement in play should only benefit coparenting in families in which parents hold less nontraditional beliefs about fathers. In fact, we found that father involvement in play only had a positive impact on coparenting in dual-earner families (which tended to consist of parents with more - not less - nontraditional beliefs about fathers’ roles).

Limitations

Even as this study had a number of strengths, including the measurement of two important aspects of father involvement - caregiving and play - and the use of both observations and self-reports of coparenting behavior, some limitations must also be acknowledged. Although considering fathers’ perceptions of their involvement with their children and not relying on mothers’ reports of fathers’ behavior (which likely underestimate father involvement and may have less predictive validity; see Hernandez & Coley, 2007) represents an improvement upon much previous research, including mothers’ as well as fathers’ perceptions of father involvement may be an even better approach. In addition, we measured the frequency of fathers’ involvement in developmentally appropriate caregiving and play activities, but did not directly assess the observed quality of father-child interactions or relationships. Future research on links between father involvement and coparenting should also include more qualitative measures of fathering behavior. Moreover, when questioned, most fathers do not think that face-to-face interactions are the only way that they contribute to their children’s development, and researchers concur (Hawkins & Palkovitz, 1999). Thus, future work could benefit from the inclusion of broader measures of fathers’ commitment to their children and families as well (e.g., cognitive monitoring, McBride, Schoppe-Sullivan, et al., 2005).

It is also imperative to emphasize that these data were collected at one point in time. Therefore, it is unclear whether father involvement affects coparenting behavior, as we have argued, or whether coparenting relationships provide a context that can either foster or inhibit different types of fathering behavior (dependent, as demonstrated in this study, on family earner status). We postulate that a reciprocal relationship likely exists. However, future research is needed in order to determine whether the patterns existing in the present study are maintained across time. It is also important to consider that family systems experience periods of homeostasis and change (Minuchin, 1974), and these changes are often sparked by changes in children’s development. Thus, the nature of the associations between father involvement and coparenting behavior may be different when measured concurrently versus across time, and may also differ for families with children of different ages.

Additionally, our sample was moderate in size and limited in terms of its racial/ethnic and socioeconomic diversity. More specifically, our sample was highly educated and relatively wealthy. The single-earner families were largely single-earner families by choice, and the dual-earner families held jobs that afforded parents advantages such as flexible schedules. Dual-earner families with such advantages and families with one parent who has the earning power to serve as the sole provider may differ in important ways from the larger population of dual- and single-earner families. Thus, the characteristics of our sample limit the generalizability of our findings. We also limited the sample to community families headed by two married or cohabitating parents. Therefore, we are unable to generalize the results of our study to families in which parents or children are experiencing significant mental health, relationship, or behavior problems, to divorced families, or to families with non-residential fathers. The relations among father involvement and coparenting behavior are likely different in these families. Future research is needed to address these issues and broaden the scope of our knowledge.

Conclusion

Although previous investigations of father involvement and coparenting behavior have largely been conducted independently, results of this study confirm the importance of examining both of these aspects of the family system together when trying to understand the intricate system of relationships that serves as a primary context for children’s development. In particular, the present study demonstrated that the extent to which high levels of father involvement are related to adaptive coparenting behavior may differ by type of involvement and for families with different employment patterns. As Lamb (1997) speculated, “the benefits obtained by children with highly involved fathers are largely attributable to the fact that high levels of paternal involvement created family contexts in which parents felt good about their marriages and the child care arrangements they had been able to work out.” (p. 12). As such, it is imperative that researchers continue to consider the larger family context, including the quality of coparental and other family relationships, when studying fathering behavior and when drawing conclusions about the implications of father involvement for children’s development and functioning.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the support of the NICHD for this research (HD 050235). We would also like to thank the families who participated in this study and the students who assisted with data collection and coding, especially Claire Cook, Evan Davis, Kimberly Snyder, Britt Thompson, and Arielle Weldon. Finally, thanks to Stephen Petrill and Carolyn Reed for comments on an earlier draft of this paper.

Footnotes

This paper was derived from the first author’s master’s thesis. Portions of this work were also presented at the 2006 National Council on Family Relations conference, Minneapolis, Minnesota.

The wide age range of the participating parents is because of one set of older parents in our sample (ages 56.2 and 56.7 years).

To simplify its use in the regression analyses, the family income variable was dichotomized and dummy coded. Families with an income at or below the median (n = 35) were assigned “0”, and families with an income above the median (n = 43) were assigned “1”.

Contributor Information

Catherine K. Buckley, Department of Child Development and Family Studies, Purdue University

Sarah J. Schoppe-Sullivan, Department of Human Development and Family Science, The Ohio State University

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Allen SM, Hawkins AJ. Maternal gatekeeping: Mothers’ beliefs and behaviors that inhibit greater father involvement in family work. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1999;61:199–212. [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR. Father-child relations, mother-child relations, and offspring psychological well-being in early adulthood. Journal of the Marriage and the Family. 1994;56:1031–1042. [Google Scholar]

- Beitel AH, Parke RD. Paternal involvement in infancy: The role of maternal and paternal attitudes. Journal of Family Psychology. 1998;12:268–288. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Putnam S, Crnic K. Coparenting, parenting, and early emotional development. In: McHale JP, Cowan PA, editors. Understanding how family level dynamics affect children’s development: Studies of two-parent families. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1996. pp. 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Blair SL, Wenk D, Hardesty C. Marital quality and paternal involvement: Interactions of men’s spousal and parental roles. Journal of Men’s Studies. 1994;2:221–237. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera N, Moore K, Bronte-Tinkew J, Halle T, West J, Brooks-Gunn J, et al. The DADS initiative: Measuring father involvement in large-scale surveys. In: Day RD, Lamb ME, editors. Conceptualizing & measuring father involvement. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2004. pp. 417–452. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan CP, Cowan PA. Unpublished coding scales. University of California; Berkeley: 1996. Schoolchildren and their families project: Description of coparenting style ratings. [Google Scholar]

- Crouter AC, Perry-Jenkins M, Huston TL, McHale SM. Processes underlying father involvement in dual-earner and single-earner families. Developmental Psychology. 1987;23:431–440. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch FM. Equally shared parenting. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2001;10:25–28. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch FM, Servis LJ, Payne JD. Paternal participation in child care and its effects on children’s self-esteem and attitudes toward gendered roles. Journal of Family Issues. 2001;22:1000–1024. [Google Scholar]

- Doherty WJ, Kouneski EF, Erickson MF. Responsible fathering: An overview and conceptual framework. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1998;60:277–292. [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg ME. The internal structure and ecological context of coparenting: A framework for research and intervention. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2003;3:95–131. doi: 10.1207/S15327922PAR0302_01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flouri E, Buchanan A. The role of father involvement in children’s later mental health. Journal of Adolescence. 2003;26:63–78. doi: 10.1016/s0140-1971(02)00116-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flouri E, Buchanan A. Early father’s and mother’s involvement and child’s later educational outcomes. British Journal of Educational Psychology. 2004;74:141–153. doi: 10.1348/000709904773839806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green SB. How many subjects does it take to do a regression analysis? Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1991;26:499–510. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr2603_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grych JH, Clark R. Maternal employment and development of the father-infant relationship in the first year. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:893–903. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.4.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackel LS, Ruble DN. Changes in the marital relationship after the first baby is born: Predicting the impact of expectancy disconfirmation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;62:944–957. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.62.6.944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins AJ, Palkovitz R. Beyond ticks and clicks: The need for more diverse and broader conceptualization and measures of father involvement. Journal of Men’s Studies. 1999;8:11–32. [Google Scholar]

- Hays WL. Statistics. New York: Holt, Rinehart, & Winston; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez DC, Coley RL. Measuring father involvement within low-income families: Who is a reliable and valid reporter? Parenting: Science and Practice. 2007;7:69–97. [Google Scholar]

- Hofferth SL, Pleck J, Stueve JL, Bianchi S, Sayer L. The demography of fathers: What fathers do. In: Tamis-LeMonda CS, Cabrera N, editors. Handbook of father involvement. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2002. pp. 63–90. [Google Scholar]

- Lamb ME, editor. The role of the father in child development. 3. New York: Wiley; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Lamb ME, Pleck JH, Charnov EL, Levine JA. A biosocial perspective on paternal behavior and involvement. In: Lancaster JB, Altmann J, Rossi AS, Sherrod LR, editors. Parenting across the lifespan: Biosocial dimensions. Hawthorn, NY: Aldine Publishing Co; 1987. pp. 111–142. [Google Scholar]

- Lee CS, Doherty WJ. Marital satisfaction and father involvement during the transition to parenthood. Fathering. 2007;5:75–96. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis C, Lamb ME. Fathers’ influences on child development: The evidence from two-parent families. European Journal of Psychology of Education. 2003;18(2):211–228. [Google Scholar]

- Liebetrau AM. Measures of association. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Margolin G, Gordis EB, John RS. Coparenting: A link between marital conflict and parenting in two-parent families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15:3–21. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.15.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglio W, Amato P, Day RD, Lamb ME. Scholarship on fatherhood in the 1990s and beyond. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2000;62:1173–1191. [Google Scholar]

- McBride BA, Schoppe-Sullivan SJ, Ho MR. The mediating role of fathers’ school involvement on student achievement. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2005;26:201–206. [Google Scholar]

- McHale JP, Johnson D, Sinclair R. Family dynamics, preschoolers’ family representations, and preschool peer relationships. Early Education and Development. 1999;10:373–401. [Google Scholar]

- McHale J, Khazan I, Erera P, Rotman T, DeCourcey W, McConnell M. Coparenting in diverse family systems. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of parenting. 2. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2002. pp. 75–107. [Google Scholar]

- McHale JP, Rasmussen JL. Coparental and family group-level dynamics during infancy: Early family precursors of child and family functioning during preschool. Development and Psychopathology. 1998;10:39–59. doi: 10.1017/s0954579498001527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHale JP, Rotman T. Is seeing believing? Expectant parents’ outlooks on coparenting and later coparenting solidarity. Infant Behavior & Development. 2007;30:63–81. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minuchin S. Families and family therapy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Mosley J, Thomson E. Fathering behavior and child outcomes: The role of race and poverty. In: Marsiglio W, editor. Fatherhood: Contemporary theory, research, and social policy. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1995. pp. 148–165. [Google Scholar]

- Nangle SM, Kelley ML, Fals-Stewart W, Levant RF. Work and family variables as related to paternal engagement, responsibility, and accessibility in dual-earner couples with young children. Fathering. 2003;1:71–90. [Google Scholar]

- Palkovitz R. Parental attitudes and fathers’ interactions with their 5-month-old infants. Developmental Psychology. 1984;20:1054–1060. [Google Scholar]

- Paquette D. Theorizing the father-child relationship: Mechanisms and developmental outcomes. Human Development. 2004;47(4):193–219. [Google Scholar]

- Parke RD, McDowell DJ, Kim M, Killian C, Dennis J, Flyer ML, et al. Father’s contributions to children’s peer relationships. In: Tamis-LeMonda CS, Cabrera N, editors. Handbook of father involvement. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2002. pp. 141–166. [Google Scholar]

- Pleck EH, Pleck JH. Fatherhood ideals in the United States: Historical dimensions. In: Lamb ME, editor. The role of the father in child development. 3. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1997. pp. 33–48. [Google Scholar]

- Pleck JH, Masciadrelli BP. Parental involvement by U.S. residential fathers: Levels, sources, and consequences. In: Lamb ME, editor. The role of the father in child development. 4. New York: Wiley; 2004. pp. 222–271. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. Computational tools for probing interaction effects in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2006;31:437–448. [Google Scholar]

- Roggman LA, Boyce LK, Cook GA, Christiansen K, Jones D. Playing with daddy: social toy play, early head start, and developmental outcomes. Fathering. 2004;2:83–108. [Google Scholar]

- Schoppe SJ. Unpublished manuscript. University of Illinois; Urbana-Champaign: 2001. What is a Father? [Google Scholar]

- Schoppe SJ, Mangelsdorf SC, Frosch CA. Coparenting, family process, and family structure: Implications for preschoolers’ externalizing behavior problems. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15:526–545. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.15.3.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoppe-Sullivan SJ, Brown GL, Cannon EA, Mangelsdorf SC, Sokolowski MS. Maternal gatekeeping, coparenting quality, and fathering behavior in families with infants. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:389–398. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.3.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoppe-Sullivan SJ, Mangelsdorf SC, Frosch CA, McHale JL. Associations between coparenting and marital behavior from infancy to the preschool years. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18:194–207. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.1.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoppe-Sullivan SJ, McBride BA, Ho MR. Unidimensional versus multidimensional perspectives on father involvement. Fathering. 2004;2:147–163. [Google Scholar]

- Schoppe-Sullivan SJ, Weldon AH, Cook JC, Davis EF, Buckley CK. Coparenting behavior moderates longitudinal relations between effortful control and preschool children’s externalizing behavior. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50:698–706. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.02009.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stright AD, Bales SS. Coparenting quality: Contributions of child and parent characteristics. Family Relations. 2003;52:232–240. [Google Scholar]

- Stright AD, Neitzel C. Beyond parenting: Coparenting and children’s classroom adjustment. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2003;27:31–39. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. America’s Family and Living Arrangements: 2005 - Table FG1. 2006 Retrieved July 6, 2007, from http://www.census.gov/population/socdemo/hh-fam/cps2005/tabFG1-all.csv.

- Volling BL, Belsky J. Multiple determinants of father involvement during infancy in dual-earner and single-earner families. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1991;53:461–474. [Google Scholar]

- Volling BL, Belsky J. The contribution of mother-child and father-child relationships to the quality of sibling interaction: A longitudinal study. Child Development. 1992;63:1209–1222. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]