Abstract

Little is known about whether patients with chronic pain treated with opioids experience craving for their medications, whether contextual cues may influence craving, or if there is a relationship between craving and medication compliance. We hypothesized that craving for prescription opioids would be significantly correlated with the urge for more medication, preoccupation with the next dose, and current mood symptoms. We studied craving in 62 patients with chronic pain who were at low or high risk for opioid misuse, while they were enrolled in an RCT to improve prescription opioid medication compliance. Using electronic diaries, patients completed ratings of craving at monthly clinic visits and daily during a 14 day take-home period. Both groups consistently endorsed craving, whose levels were highly correlated (p<.001) with urge, preoccupation, and mood. The intervention to improve opioid compliance in the high risk was significantly associated with a rate of decrease in craving over time in comparison to a high-risk control group (p<.05). These findings indicate that craving is a potentially important psychological construct in pain patients prescribed opioids, regardless of their level of risk to misuse opioids. Targeting craving may be an important intervention to decrease misuse and improve prescription opioid compliance.

Keywords: craving, noncancer pain, opioid therapy, opioid misuse, substance abuse

INTRODUCTION

Craving has been described as a strong desire for or urge to imbibe psychoactive substances, such as drugs, alcohol, and tobacco.9 Colloquially, in English-speaking cultures ‘craving something’ implies a lack of control over use of that substance.9 Indeed, studies indicate that craving is a powerful predictor for relapse in heroin and cocaine.15, 19 Thus, important principles in the treatment of addiction and the prevention of relapse are the assessment of craving, attempts to extinguish it, and helping patients to cope with craving.8, 22 Craving can be thought of as a psychological reaction (with physiological underpinnings) to avoid the negative affect associated with drug withdrawal, such as dysphoria, anxiety, or anhedonia.22

Patients with chronic pain taking prescribed opioids, and not demonstrating signs of addiction, may experience psychoactive effects of the medication such as euphoria.24 We have demonstrated in such patients that reports of craving for prescription opioids are associated with an elevated rate of opioid misuse.21 Among 455 patients prescribed opioids for pain, those who reported craving the medication (55%) had twice the rate of opioid misuse.

The American Academy of Pain Medicine (AAPM), The American Pain Society (APS), and The American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) define prescription opioid addiction in patients with pain as “a primary, chronic, neurobiologic disease that is characterized by behaviors that include one of more of the following: impaired control over drug use, compulsive use, continued use despite harm, and craving.”17 These behaviors may be perpetuated by a physiologic drive that comes with using prescription opioids,13 in which mesolimbic motivational circuits are “hijacked,” creating a disorder of motivated behavior.7, 12 For many pain medicine and addiction specialists, this definition is preferred in patients prescribed opioids for pain over the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-IV) definition of substance dependence, because unlike the DSM-IV definition, the criteria for prescription opioid addiction includes craving and does not include physical dependence. APS, AAPM, and ASAM define substance misuse in this patient group as the use of any drug in a manner other than how it is indicated or prescribed.17 Substance abuse is defined as the use of any substance when such use is unlawful, or when such use is detrimental to the user or others.

Thus, opioid misuse may indicate a treatment adherence issue, or may signal a more serious addiction problem, if accompanied by a lack of control over use despite negative consequences. These distinctions can be blurred, and in a clinical pain medicine practice it is often unclear whether a patient is simply noncompliant with their medication or addicted. The presence of craving is central to this distinction in applying the addiction criteria. It remains unclear to what extent craving is indicative of prescription opioid addiction since those without opioid addiction have also reported some craving.21 And yet, reports of craving are significantly associated with a substance use disorder.6, 19 Few studies have focused on craving among patients with pain prescribed opioids and the relationship of craving to risk for opioid misuse. We know very little about what the components of craving may be and whether it changes over time, despite its importance in diagnosing prescription opioid addiction.

The purpose of this study is to characterize self-reports of craving in patients prescribed opioids for chronic pain and to examine the relationships between opioid compliance interventions, self-reports of craving, and opioid misuse. It was hypothesized that craving would be significantly associated with 1) the desire to take more opioids, 2) preoccupation with the next dose, and 3) mood symptoms affecting the urge to take more mediation. We also hypothesized that report of craving would be reduced with frequent monitoring (urine screens and compliance checklists) and motivational counseling (individual and group sessions).

Methods

Participants, study design, and eligibility

This was a prospective, longitudinal, descriptive, cohort study of craving for prescription opioids. This data was collected while subjects were enrolled in a randomized clinical trial (RCT) of a behavioral intervention to improve prescription opioid compliance (NCT# 00988962). Subjects were patients with noncancer pain treated in a pain medicine specialty clinic. Full details of the interventional study have been previously published.10 A brief description of the RCT and the craving study methods are described below.

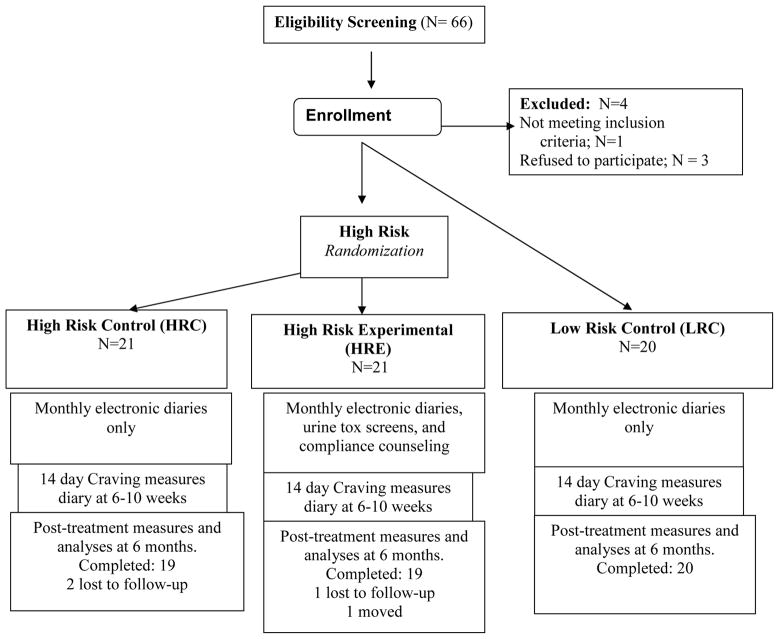

The Human Subjects Committee of Brigham and Women’s Hospital (Boston, MA) approved this study’s procedures and written informed consent was obtained from every subject. All patients were recruited through the Pain Management Center of Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Patients with back or neck pain, with or without radicular symptoms, were recruited to participate in this 6-month trial. Subjects were divided into High Risk Experimental (HRE), High Risk Control (HRC), and Low Risk Control Groups (LRC, see Figure 1 for CONSORT diagram). Patients were eligible if they: (1) had chronic back or neck pain for > 6 months’ duration, (2) averaged 4 or greater on a pain intensity scale of 0 to 10 with medication, and (3) had been prescribed opioid therapy for pain for > 6 months.

Figure 1.

Study schema.

Patients were excluded from participation if they had: (1) a current diagnosis of cancer, any other malignant disease, acute osteomyelitis, or acute bone disease, (2) present or past DSM-IV diagnosis of schizophrenia, delusional disorder, psychotic disorder, or dissociative disorder, or (3) current substance dependence, addiction, or abuse of any kind within the past year (at enrollment, positive on the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; M.I.N.I. v.5.018 and/or meeting the AAPM and ASAM criteria for prescription opioid addiction described above).

Chronic opioid treatment

Patients were evaluated by one of five board-certified pain medicine physicians who all had at least five years of consultant-level experience. Each subject received a complete history, physical, and review of radiological studies. All subjects were maintained on their current opioid medication and asked to remain on a stable dose throughout the study period. The physician evaluation included an assessment of the appropriateness of the current opioid dose(s) as well as the specific opioid used and adjustments were made, if indicated, prior to enrollment. All other adjuvant medication remained constant through the course of the 6-month trial. Prescriptions of immediate release (IR) opioids for breakthrough pain and long-acting opioids were based on physician decision. All prescription medications were carefully monitored by the study manager through the use of electronic diaries and monthly contacts. Medication was prescribed once per month unless decided otherwise by the treating physician.

Enrollment Criteria

Subjects were determined to be at high risk for prescription opioid misuse based on a positive indication on any of the following criteria: 1) their responses on the Revised Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain2 (SOAPP-R; score > 18 for misuse), 2) opioid misuse based on physician report (Addiction Behavior Checklist, ABC > 2 for aberrant drug behaviors)23, or 3) abnormal urine screens. The SOAPP-R is a 24-item, self-administered screening instrument used to assess suitability of long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain patients to help determine risk potential for future opioid misuse. Items are rated from 0=never to 4=very often. The SOAPP-R has been shown to have good predictive validity, with an area under the curve ratio of 0.88 (95% confidence interval [CI], .81–.95). A cutoff score of 18 shows adequate sensitivity (.86) and specificity (.73) for predicting prescription opioid misuse.2 We also examined the responses on item #11 of the SOAPP-R, “How often have you felt a craving for medication?”

The ABC is a 20-item instrument designed to track behaviors characteristic of aberrant drug behaviors related to prescription opioid medications in chronic pain populations. Items are focused on observable behaviors during and between clinic visits. This checklist was found to have adequate validity and reliability. A cut-off score of 3 or greater showed optimal sensitivity and specificity in determining whether a patient is displaying inappropriate opioid use.23

Description of the RCT intervention and treatment groups

Those at high risk of opioid misuse were randomly assigned to High Risk Control (HRC) or High Risk Experimental (HRE) treatment arms. Those in the High-Risk Control group were maintained on their current opioid regimen and were seen on a monthly basis at the Pain Management Center. They completed electronic diaries and had monthly contact with their physician. They represented the usual treatment control condition. They submitted a urine sample for gas chromatography, mass spectroscopy (GCMS) screening for prescription opioids, illegal drugs, and alcohol at study entry and at the end of the six month study period. The High-Risk Experimental Group received the same medical treatment as the High-Risk Controls plus participated in a structured cognitive behavioral training program for prevention of substance abuse, as well as receiving monthly urine screens. Of note, craving was not a specific topic of group discussion or a target of the intervention.

For additional comparative purposes, we identified patients with chronic back or neck pain who had been prescribed long-acting opioids for pain for > 6 months and showed no signs of medication misuse. They had SOAPP-R scores of <18, had a history of compliance with opioid medication based on physician report and ABC scores ≤ 2, and had appropriate urine toxicology screens. These patients, who met criteria for low-risk for opioid misuse (Low Risk Control, LRC), completed monthly electronic diaries, were maintained on their opioid therapy regimen, were followed for a minimum of 6 months, and submitted a GCMS urine screen at study entry and completion, which were identical procedures to the HRC group (Fig. 1). All subjects received $50 gift cards for completing the baseline and post-treatment measures.

Additional Measures

The Brief Pain Inventory (BPI):3

This self-report questionnaire is a well-known measure of clinical pain and evidences sufficient reliability and validity. The questionnaire provides information about pain history, intensity, and location as well as the degree to which the pain interferes with daily activities, mood, and enjoyment of life. Scales (rated from 1 to 10) indicate the intensity of pain in general, at its worst, at its least, average pain, and pain “right now.”

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS):25

The HADS is a 14-item scale without somatic items, designed to assess the presence and severity of anxious and depressive symptoms in medically ill populations. Seven items assess anxiety and seven items measure depression, each coded from 0 to 3 with different descriptive anchors. The HADS has been used extensively in patients with pain and has adequate reliability (Cronbach’s Alpha = .83) and validity, with optimal balance between sensitivity and specificity to predict the presence or absence of a DSM-IV major depression or generalized anxiety disorder.1

Prescription Drug Use Questionnaire (PDUQ):4

This 42-item structured interview is probably the most well-developed abuse-misuse assessment instrument for pain patients at this time.16 The PDUQ is a 20-minute interview during which the patient is asked about his or her pain condition, opioid use patterns, social and family factors, family history of pain and substance abuse, and psychiatric history. In an initial test of the psychometric properties of the PDUQ, the standardized Cronbach’s alpha was 0.79, suggesting acceptable internal consistency. Compton and her colleagues suggested that subjects who scored below 11 did not meet criteria for a substance use disorder, while whose with a score of 11 or greater showed signs of a substance use disorder.

Table 1 displays baseline pain levels, activity interference ratings, mood symptoms, and opioid compliance measures. No clinically meaningful or statistically significant differences between groups were found on the pain, function, or mood variables. The high risk groups were significantly different than the low risk group on opioid compliance measures on study entry (SOAPP-R, ABC, and abnormal urine rates).

Table 1.

Baseline comparisons of groups on demographic, pain intensity, function (BPI), mood (HADS), and craving item (How often crave medication).

| Variable | High Risk Control (N=21) | High Risk Experimental (N=21) | Low Risk Control (N=20) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 46.57±6.78 | 47.00±7.75 | 49.55±6.80 |

| Gender (%male) | 57.1 | 47.6 | 65.0 |

| Avg. pain | 6.24±2.07 | 5.86±1.89 | 5.85±1.76 |

| Pain now | 6.14±2.63 | 6.00±2.47 | 6.25±2.45 |

| % Pain relief from medications | 60.24±25.42 | 57.00±25.57 | 55.79±24.57 |

| Pain Interference with: | |||

| Activity | 6.86±2.67 | 6.52±2.58 | 5.75±1.73 |

| Mood | 4.95±3.29 | 5.71±2.61 | 4.55±2.42 |

| Walking | 6.62±3.14 | 5.14±3.43 | 5.79±2.35 |

| Work | 7.48±3.04 | 6.76±2.98 | 6.83±2.07 |

| Relations with others | 4.24±3.53 | 4.38±2.87 | 3.95±2.46 |

| Sleep | 6.14±3.47 | 6.29±3.18 | 6.45±2.19 |

| Enjoying Life | 6.05±3.03 | 5.81±2.91 | 5.95±2.83 |

| HADS-Anxiety | 8.10±3.48 | 7.43±3.84 | 6.40±3.35 |

| HADS-Depression | 8.43±3.61 | 7.14±3.97 | 6.15±3.95 |

| SOAPP-R | 23.14 ± 9.63a | 18.57 ± 9.31a | 13.25 ± 6.77b |

| ABC | 2.60 ± 3.28a | 2.52 ± 3.43a | 0.70 ± 1.72b |

| Abnl Urines (%) | 39.1c | 37.0c | 5.5d |

| Craving | 10.1 ± 11.9 | 6.4 ± 9.5 | 4.5 ± 7.6 |

| Urge | 19.9 ± 25.5 | 15.1 ± 21.2 | 10.9 ± 18.8 |

| Mood affect urge | 10.1 ± 15.9 | 7.7 ± 10.2 | 9.6 ± 17.1 |

| Think about dose | 20.0 ± 23.7 | 9.3 ± 13.9 | 7.1 ± 10.5 |

p < 0.05 Bonferroni corrected.

p < 0.001 Bonferroni corrected.

How often; never, seldom, sometimes, often

Drug misuse outcome assessment during the RCT

Data on urine toxicology results, the ABC, and Prescription Drug Use Questionnaire (PDUQ) allowed for group comparisons during the RCT. Outcome was assessed based on the percent of patients with a positive Drug Misuse Index at the end of the 6 month study (DMI, positive or negative for misuse). This is a composite measure triangulating urine screen results, staff ratings of abuse behavior (ABC > 2), and results of the PDUQ (>11) over the course of 6 months. Abnormal urine toxicology screens were categorized in the following ways: 1) negative (i.e., normal urine or equivocal results), 2) positive for illicit substances or alcohol (evidence of marijuana, cocaine, ethanol, phencyclidine), and/or 3) positive for a prescription opioid not prescribed or not known to be a metabolite. We decided not to count the absence of a prescribed opioid as abnormal, since there are many reasons other than diversion that could account for this result (such as running out appropriately of opioid prior to the clinic visit). This system of determining drug misuse has been used as an outcome measure by the authors in previous studies.20, 21 Despite both high risk groups having a similar, elevated risk for opioid misuse at study entry, over the course of six months the HRE Group had a significantly lower rate of opioid misuse (positive DMI=26.3%) than the HRC Group (73.7 %, p<.01). The High Risk Experimental Group had a rate of misuse approximately equivalent to the Low Risk Control Group (25%).10

Craving Measures on Electronic diaries

In-clinic diaries

All patients monitored their progress with the use of electronic diaries once a month during each clinic visit (6-month longitudinal component). The pain electronic calendar 11 comprises a comprehensive set of 25 items, incorporating key questions from the Brief Pain Inventory (severity, activity, function and mood), medication questions, and location of pain (pain diagram). The devices consisted of a Hewlett Packard © IPAQ personal digital assistant (PDA). Diary data was downloaded and used to summarize changes in level of pain and activity interference.

The diaries also included four questions rated on a 0–100 visual analog scale (VAS) to assess craving for prescription opioids over the past 24 hours: 1) How strong was your urge to take more opioid medication than prescribed? 2) How much did your mood or anxiety level affect any urge to take more opioid medication? 3) How often have you found yourself thinking about the next opioid dose? and, 4) How much have you craved the medication? These items were based on the Cocaine Craving Scale validated by Weiss and colleagues.22

At-home diaries

Subjects also completed the craving measures and ratings of pain on the PDA for 14 days on a daily basis (signaled by an alarm, 14-day intensive component). This occurred between weeks 6–10 of the 24 week study, depending on the availability of the take-home diaries. This time period was chosen so that the HRE Group would have had some exposure to the drug misuse intervention prior to completing the intensive craving monitoring period. As a result, these data do not represent baseline ratings.

Statistical Analyses

The responses to the 6-month and 14-day craving items were the primary outcomes evaluated in this study. The primary hypothesis tested was that the craving items would be significantly related to each other during the 6-month and 14-day periods. Secondary, exploratory hypotheses tested were; 1) levels of craving would be poorly related to levels of pain intensity, 2) the High Risk Control Group would demonstrate significantly higher levels of craving during the 6-month observation period compared with the other two groups, and 3) levels of craving would be positively correlated to the incidence of opioid misuse (DMI score). All data were analyzed with SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences; Chicago, IL) v.17.0. The main analyses were conducted according to a modified intent-to-treat principle. Patients would be included in the group to which they were originally randomized regardless of whether they completed the intervention assigned and regardless of whether they had missing data as a result of missed visits, with the caveat that the subjects had to have completed at least 3 months of the monthly craving assessments.

Relations among demographic data, interview items, questionnaire data, physician ratings, and urine toxicology results in relation to group were analyzed using Pearson correlations, Chi-square, and analysis of variance (ANOVA) analyses, depending on whether the variables were ordinal or numerical. Linear mixed modeling was used to analyze the relationships between craving levels over time and group. For the 6-month and 14-day craving data, group, time, and group X time were entered as fixed effects using an autoregressive heterogeneous covariance structure. Subject, intercept, and time were entered as random effects, with month or day as repeated random effects, using an unstructured covariance structure. This approach controls for possible differences in baseline craving values in examining whether craving changed differently over time between groups. Logistic regression was used to analyze the relationship between craving and opioid misuse.

Results

Baseline comparisons on demographic variables, pain, function, mood, and the craving items among the three groups are presented in Table 1. No differences were found among the three groups on age, gender, pain, and responses on the BDI and HADS questionnaires. Table 1 also presents differences on the SOAPP-R, ABC, urine screen results, and the craving questions among the groups at study entry. The High-risk subjects had significantly higher SOAPP-R and ABC scores and had a much higher percentage of abnormal urine toxicology screens. The High-risk subjects also reported craving their medication more than the Low-risk subjects based on item #11 of the SOAPP-R (“How often have you felt a craving for medication” 0=never; 4=very often). Mean baseline ratings of the four craving items at session 1 showed that the HRC group had higher baseline values than the HRE and LRC groups, but these differences were not statistically significant. Overall, 38 patients (61.3%) denied any craving at baseline (0, on a 0–100 scale). The results showed no significant differences between those who admitted to craving medication (>0) and those who did not on demographic variables (e.g., age, gender) anxiety (HADS), depression (HADS), pain disability (PDI), and PDUQ, although predicted differences were in the right direction (SOAPP-R item 11 “no craving” PDUQ = 8.30 ±4.36; SOAPP-R item 11 “some craving” PDUQ = 10.04 ±5.26).

Table 2 displays the Pearson correlation coefficients among the 4 craving items (craving level, urge, urge related to mood, and preoccupation with next dose) and pain for the 6-month data. The craving items were highly correlated (.66 – .82) and much less correlated with pain levels (.07 – .19). Among the 4 craving items, the Cronbach’s alpha score was .91, p<.001. The craving items were modestly correlated to mood items on the HADS questionnaire. Baseline depression and anxiety subscale scores had correlation coefficients to baseline craving items ranging between .20 and .30. The correlations among the craving items during the 14-day take-home diary period were similar to the 6-month in-clinic results (not displayed). Correlations ranged between .67 and .85, and correlations of craving items to pain were between .13 and .26.

Table 2.

Correlations between craving diary items and pain over 6 months (N=360 entries).

| Variables | How much craving | Mood affect craving | Think about next dose | Urge to take more | Ave Pain 24 hrs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mood affect craving | .73** | ||||

| Think about Next dose | .82** | .66** | |||

| Urge to take more | .71** | .77** | .73** | ||

| Ave Pain 24 hrs. | .07 | .07 | .07 | .07 | |

| Pain now | .17* | .17* | .15* | .19* | .69* |

p<0.01

p<0.001

Monthly Craving Data

Table 3 summarizes the means of the electronic diary questions related to the use of medication and craving over the 6-month study. Significant differences were found between the HRC subjects and those in the HRE and LRC groups. The HRC group consistently rated all of these items significantly higher than subjects in the other two groups (p<0.05). Across the three groups, craving opioid medication was rated the lowest of the four questions, while the highest ratings and greatest differences between groups were found on the urge to take more medication than prescribed. It needs to be pointed out that the subjects started the diaries at different times during the study and these results do not reflect baselines ratings.

Table 3.

Average 6-month, in-clinic electronic diary ratings of medication and craving variables (mean, std. dev.)

| Variable Over the last 24 hours (0–100) | High-Risk Control (N=19) | High-Risk Experimental (N=19) | Low-Risk Control (N=20) | F-values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urge to take more medication than prescribed± | 26.2 (26.5)a | 13.1 (21.6)b | 14.0 (18.4)b | 12.3*** |

| Mood affect urge to take more meds+ | 21.6 (26.4)a | 10.6 (18.9)b | 12.0 (18.0)b | 9.0*** |

| How often thinking about next dose+ | 22.2 (24.4)a | 12.9 (18.0)b | 13.2 (18.1)b | 7.7*** |

| How much have you craved your medications+ | 15.0 (20.1)c | 9.0(16.6)d | 8.7 (14.7)d | 4.8** |

0=not at all; 50=moderate; 100=as much as possible

0=not at all; 50=moderate; 100=strong as possible

p<0.01;

p<0.001

Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons, p<.01

Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons, p<.05

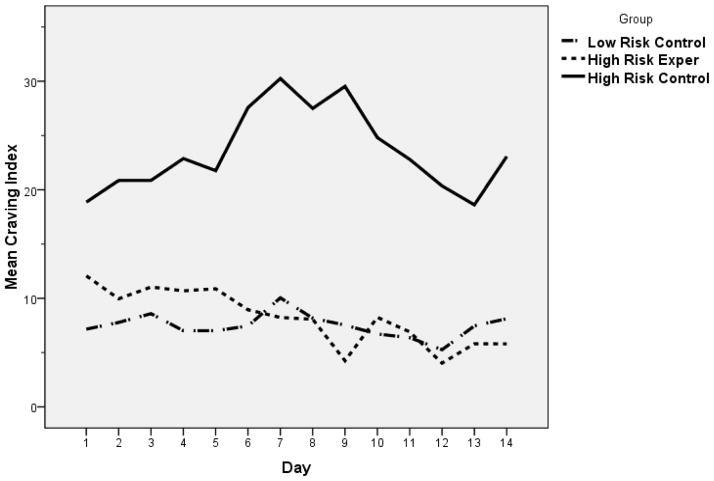

Since the craving items were highly interrelated and appeared to describe an underlying construct, the four items were averaged at each time point to create a “Craving Index” value (CI, ranging from 0–100). These values were then used to analyze changes in craving over time for each group using linear mixed modeling. For the six-month data, 68% percent of all subjects had a CI >0 at baseline (study entry). At baseline the three groups differed significantly on the mean craving index (mean (SE): HRC=26.7 (6.4), HRE=11.0 (3.3), LRC=13.9 (3.2), p<.05). This pattern continued over 6 months in the mean CI values (HRC=21.5 (3.1), HRE=10.7 (3.4), LRC=11.7 (3.3), p<.01), and with the end of study mean CI values (HRC=24.5 (4.0), HRE=9.6 (4.4), LRC=9.4 (4.2), p<.05). While the CI values varied by month, these differences were not statistically significant in the multivariate model. Forty six percent of subjects had an average CI >10 over 6 months. In comparison to the HRC group, the HRE group had a statistically significant rate of decrease in the mean CI value over time (Beta= −2.4, p<.05).

Daily Craving Data

Figure 2 displays the 14-day take-home diary CI calculations, and these patterns mimic the 6-month data. At day one, the HRC group had a higher mean CI value, but these group differences were not statistically significant. Day was not a significant predictive factor in the multivariate model. In comparison to the HRC group, the HRE group had a statistically significant rate of decrease in the mean CI value over time (Beta= −.9, p<.05). Overall, the 6-month and 14-day data had similar patterns in that the HRC group tended to slightly rise over time, the HRE group tended to slightly decrease over time, and the LRC group remained the same.

Figure 2.

Craving index versus day

Craving and Drug Misuse

Using logistic regression to examine whether the craving index predicted drug misuse (DMI), the average CI level over the six-month study was a significant univariate predictor of DMI (Wald statistic=3.9, p<.05). But when added to a multivariate model of Group and CI, average CI was not a significant predictor. Baseline CI, end of study CI, average change in CI, or average percent change in CI over six months were not univariate or multivariate predictors of DMI.

Data Completeness

For the monthly craving measures collected with the in-clinic electronic diary, 89% of the data were complete. For the 14-day take-home diaries, 95% of the data were complete.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that many patients prescribed opioids for pain, who by standardized assessment do not meet criteria for substance dependence and are not addicted to the medication, endorse consistent reports of opioid craving. Over the course of six months of monthly ratings and within a 14-day period of daily monitoring, craving was highly correlated with the urge to take more medication, fluctuations in mood, and preoccupation with the next dose. The correlations of craving with these three factors were remarkably consistent between groups of patients with different phenotypes for opioid misuse (high versus low risk). Levels of craving were only weakly associated with current levels of pain or average pain over 24 hours. This speaks to craving as a mental experience distinct from pain itself.

The consistency between the 6-month and 14-day data indicate that craving of prescription opioids, while varying from day to day or month to month, is a relatively stable construct. These results suggest that craving is a common experience associated with prescription opioid use, which may or may not be related to the presence of a substance use disorder or any form of drug misuse behavior. The relationship between craving and risk for opioid misuse among those with chronic pain is unclear. The presence of craving in all three groups suggest that while it may be an adverse psychological symptom associated with a higher risk of opioid misuse, it may also not be a negative symptom, as illustrated by the craving levels (albeit low) in the low risk control group. Further studies are needed to determine whether a certain threshold of craving is useful an indicator for development of prescription opioid dependence and/or addiction.

One could argue that craving for prescription opioids is actually reflective of drug withdrawal in between medication doses. But the weak correlation of craving levels to pain is not consistent with this supposition. The high correlation of craving to current mood suggests that craving could be considered a negative affective state, underscoring the vulnerability of those with high negative affect to prescription opioid misuse.20 However, it is distinct from other measures of negative affect, since baseline levels of depression and anxiety symptoms were only modestly correlated to levels of craving.

While the average level of diary data craving within each of the three groups was fairly consistent over time, a summary index of craving (CI) was responsive to change in relation to a drug misuse intervention (i.e., the significant rate of decrease in craving over time in the HRE versus the HRC group). This effect was present in the 6-month and 14-day data. Since all three groups monitored craving in the same manner, our data suggests that the intervention itself had an impact on ratings of craving, and the process of monitoring it was not a significant confounder. While the CI in the HRE group significantly decreased over time in relation to the HRC group, the intervention was not designed to specifically address levels of craving, which could explain why the CI at the end of the study in the HRE group was not significantly less than at the start. Furthermore, since the level of craving in the HRE group was relatively low to begin with and comparable to the LRC group, one could argue that this “floor” effect would have mitigated the impact of any intervention on levels of craving within this group. Importantly, since the HRC group had higher baseline levels of craving than the HRE group (although not significantly different), we do not know if this higher level of craving would have precluded any response to the intervention.

To this extent, the HRE and HRC groups were not exactly matched on this important characteristic (which is often the case in RCTs with small sample sizes). Mitigating this concern is that the levels of craving were not significantly associated with the rate of drug misuse over the course of the study when examined in a multivariate logistic regression model. Perhaps our sample size was too small to discover whether this association is an important phenomena. Or, equally as likely, misuse of prescription opioids is a multifactorial phenomena influenced by such factors as pain level or mood. Nevertheless, the importance of the CI as a univariate predictor of drug misuse highlights the need to test an intervention to decrease craving or decrease the negative affect associated with craving in improving opioid compliance.

There are a number of limitations of this study that should be discussed. Unlike other studies of craving using electronic diaries,5 we did not capture reports of craving with random prompts or participant-initiated measures, and instead measured craving at designated times. Thus, our understandings of craving for prescription opioids are still somewhat limited because we do not know the situational contexts in which patients made the ratings. It is unknown what effect this collection method would have had on the quality of our data. In addition, we lack data as to whether the concept of craving is clearly understood by the persons taking opioids for pain, as noted in a previous study.21 Some equate craving with the desire not to experience pain or withdrawal from opioid medication, or with desire for relief. These issues may be on a continuum with craving, but additional attempts to define and understand the concept of craving among chronic pain patients is needed. We found that although craving is common among patients using prescription opioids, actual levels of craving are quite low. More attention is also needed in future studies to gain a greater understanding of the role of interventions for decrease craving. It is possible that the dosing frequency and individual differences in metabolizing opioids may have a direct effect on craving. Also, even though the topic of craving was never discussed, it is possible that patients in the Experimental Group reported less craving because of a need to please the investigators.

Finally, we recognize that there is no gold standard in accurately assessing drug misuse. We decided to not include the absence of a prescribed drug in the urine as abnormal since there are many reasons other than diverting that could explain this result (e.g. the patient did not take the opioid on the day they came to the clinic to get their refill or was appropriately out of drug). We also recognize that there are degrees of seriousness of misuse, and we attempted to examine this (e.g., positive urine screen for marijuana vs. cocaine), but the small group numbers restricted us from drawing any meaningful conclusions.

Overall, our data demonstrate that craving is a coherent and potentially modifiable concept to monitor in any study of prescription opioid misuse or addiction. Our results are consistent with a larger body of work on craving illustrating its salience to the diagnosis of substance use disorders. This powerful association has led the American Psychiatric Association to include craving as a criteria item for substance dependence in the forthcoming DSM-V.14 Craving for prescription opioids in patients with pain is highly correlated to the urge to take more medication, preoccupation with the next dose, and momentary levels of mood symptoms. Craving may be an important vulnerability factor influencing prescription opioid misuse. Future research should examine the effects that type of opioid (e.g., long- vs. short-acting) has on craving and further evaluate the role of adherence interventions in reducing craving among persons prescribed opioids for chronic pain. In sum, the results of this study suggest that lowering craving may be an important mechanism or therapeutic target to improve prescription opioid compliance.

Perspective.

Patients with noncancer pain can crave their prescription opioids, regardless of their risk for opioid misuse. We found craving to be highly correlated with the urge to take more medication, fluctuations in mood, and preoccupation with the next dose, and to diminish with a behavioral intervention to improve opioid compliance.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to especially thank Robert Edwards, Kathleen Howard, David Janfaza, Sanjeet Narang, Heather Thomson, Assia Valovska and staff and patients of Brigham and Women’s Hospital Pain Management Center.

This study was supported by the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA) of the National Institutes of Health (K23 DA020682, Wasan, PI) and the Arthritis Foundation (Investigator Award; Wasan, PI). It was also funded in part by an investigator-initiated grant from Endo Pharmaceuticals, Chadds Ford, PA, and NIDA grant (R21 DA024298, Jamison, PI) as well as K24 DA019855 (Greenfield PI) and K24 DA022288 (Weiss PI) from NIDA.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Contributors: All of the authors significantly contributed to the design, patient enrollment, data collection, data analysis, and manuscript preparation.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Huag TT, Neckelmann D. The validity of the hospital anxiety and depression scale. An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52:69–77. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00296-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Butler SF, Fernandez K, Benoit C, Budman SH, Jamison RN. Validation of the revised screener and opioid assessment for patients with pain (soapp-r) J Pain. 2008;9:360–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cleeland CS, Gonin R, Hatfield AK, Edmonton JH, Blum RH. Pain and its treatment in outpatients with metastatic cancer. NEJM. 1994;330:592–96. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199403033300902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Compton PJ, Darakjian J, Miotto K. Screening for addiction in patients with chronic pain and ‘problematic’ substance use: Evaluation of a pilot assessment tool. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1998;16:355–63. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(98)00110-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Epstein DH, Willner-Reid J, Massoud V, Mezghanni M, Jia-Ling L, Preston KL. Real-time electronic diary reports of acute exposure in mood in the hours before cocaine and heroin craving and use. Arch Gen Psych. 2009;66:88–94. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fareed A, Vayalapalli S, Casarella J, Amar R, Drexler K. Heroin anticraving medications: A systematic review. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2010;36:332–41. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2010.505991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fields HL. Understanding how opioids contribute to reward and analgesia. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2007;32:242–6. doi: 10.1016/j.rapm.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Franken IH. Drug craving and addiction: Integrating psychological and neuropsychopharmacological approaches. Progress Neuro-Psychopharm Bio Psychia. 2003;27:563–579. doi: 10.1016/S0278-5846(03)00081-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hormes JM, Rozin P. Does “craving” carve nature at the joints? Absence of a synonym for craving in many languages. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35:459–63. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jamison RN, Ross EL, Michna E, Chen LQ, Holcomb C, Wasan AD. Substance misuse treatment for high-risk chronic pain patients on opioid therapy: A randomized trial. Pain. 2010;150:390–400. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.02.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marceau LD, Link C, Jamison RN, Carolan S. Electronic diaries as a tool to improve pain management: Is there any evidence? Pain Med. 2007;8 (Suppl 3):S101–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2007.00374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McHugh PR, Slavney PR. Perspectives of psychiatry. 2. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nedeljkovic SS, Wasan AD, Jamison RN. Assessment of efficacy of long-term opioid therapy in pain patients with substance abuse potential. Clin J Pain. 2002;18:S39–51. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200207001-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Brien C. Addiction and dependence in dsm-v. Addiction. 2011;106:866–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03144.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosenberg H. Clinical and laboratory assessment of the subjective experience of drug craving. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29:519–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Savage S. Addiction and pain: Assessment and treatment issues. Clin J Pain. 2002;18:S28–38. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200207001-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Savage S, Covington EC, Heit HA, Hunt J, Joranson D, Schnoll SH. Definitions related to the use of opioids for the treatment of pain: A consensus document from the american academy of pain medicine, the american pain society, and the american society of addiction medicine. 2001 Available at: http://www.ampainsoc.org/advocacy/opioids2.htm.

- 18.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH. The mini international neuropsychiatric interview (m.I.N.I.): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for dsm-iv and icd-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Skinner MD, Aubin HJ. Craving’s place in addiction theory: Contributions of the major models. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2010;34:606–23. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wasan AD, Butler SF, Budman SH, Benoit C, Fernandez K, Jamison RN. Psychiatric hisotry and psychological adjustment as risk factors for aberrant drug-related behavior among patients with chronic pain. Clin J Pain. 2007;23:307–15. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3180330dc5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wasan AD, Butler SF, Budman SH, Fernandez K, Wesiss R, Greenfield S, Jamison RN. Does report of craving opioid medication predict aberrant drug behavior among chronic pain patients? Clin J Pain. 2009;25:193–98. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e318193a6c4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weiss RD, Griffin ML, Mazurick C, Gastfriend DR, Frank A, Barber JP, Blaine J, Salloum I, Moras K. The realtionship between cocaine craving, psychosocial treatment, and subsequent cocaine use. Am J Psych. 2003;160:1320–5. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.7.1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu SM, Compton P, Bolus R, Schieffer B, Pham Q, Baria A, Van Vort W, Davis F, Shekelle P, Naliboff B. The addiction behaviors checklist: Validation of a new clinician-based measure of inappropriate opioid use in chronic pain. J Pain Sym Manage. 2006;32:342–352. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zacny JP, Gutierrez S. Subjective, psychomotor, and physiological effects profile of hydrocodone/acetaminophen and oxycodone/acetaminophen combination products. Pain Med. 2008;9:433–443. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2007.00359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. ACTA Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]