Abstract

The interaction between the stress axis and endogenous opioid systems has gained substantial clinical attention as it is increasingly recognized that stress predisposes to opiate abuse. For example, stress has been implicated as a risk factor in vulnerability to the initiation and maintenance of opiate abuse and is thought to play an important role in relapse in subjects with a history of abuse. Numerous reports indicating that stress alters individual sensitivity to opiates suggest that prior stress can influence the pharmacodynamics of opiates that are used in clinical settings. Conversely, the effects of opiates on different components of the stress axis can impact on individual responsivity to stressors and potentially predispose individuals to stress-related psychiatric disorders. One site at which opiates and stress substrates may interact to have global effects on behavior is within the locus coeruleus (LC), the major brain norepinephrine (NE)-containing nucleus. This review summarizes our current knowledge regarding the anatomical and neurochemical afferent regulation of the LC. It then presents physiological studies demonstrating opposing interactions between opioids and stress-related neuropeptides in the LC and summarizes results showing that chronic morphine exposure sensitizes the LC-NE system to corticotropin releasing factor and stress. Finally, new evidence for novel presynaptic actions of kappa-opioids on LC afferents is provided that adds another dimension to our model of how this central NE system is co-regulated by opioids and stress-related peptides.

Keywords: opioids, enkephalins, dynorphin, corticotropin-releasing hormone, norepinephrine, locus coeruleus

Stress and vulnerability to drug abuse

In the midst of a perceived threat to survival, the body undergoes a number of adaptive responses aimed at mobilizing energy resources and sustaintaining arousal (Selye, 1953). This “stress response” includes an endocrine limb (involving the hypothalamic-pituitary adrenal axis activation), an autonomic limb (involving cardiovascular and gastrointestinal mobilization), an immunological limb (involving immunosuppression) and a behavioral and cognitive limb (involving enhanced arousal and alterations in attention) (Selye and Horava, 1953). The machinery underlying the coordinated function of these limbs is indispensable in effectively adapting to physiological and emotional threats. For almost three decades, multiple evidence demonstrates the role of the neuropeptide, corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) in the coordination of the stress response. CRF acting as a neurohormone and a neurotransmitter was originally characterized as the hypothalamic neurohormone that initiates the release of adrenocorticotropin from the adenohypophysis or anterior pituitary gland and consequently directs the cascade of events culminating in corticosteroid secretion (Rivier et a., 1982; Vale et al., 1981). Following the discovery of the CRF as a neurohormone, several lines of evidence support a role of CRF as a brain neurotransmitter involved in coordinating the different limbs of the stress response (Dunn and Berridge 1990; Owens and Nemeroff 1991).

Stress has been implicated as a risk factor in the vulnerability to the initiation and maintenance of opiate abuse and is thought to play an important role in relapse in subjects with a history of abuse (Gaal and Molnar, 1990; Goeders, 1998; Goeders, 2003; Hyman et al., 2007; Ilgen et al., 2008; Piazza and Le Moal, 1997; Piazza and Le Moal, 1998; Shaham et al., 1998; Shaham et al., 1997; Sinha et al., 2006; Zhou et al., 1996). However, the impact of stress-opioid interactions extends beyond vulnerability to opiate abuse. Numerous reports indicate that stress alters individual sensitivity to opiates and suggest that prior stress can influence the pharmacodynamics of opiates that are used in clinical settings (Benedek and Szikszay, 1985; Christie and Chesher, 1982; Christie et al., 1982; Hyman et al., 2007; Sinha, 2001; Sinha et al., 1999; Sinha et al., 2007; Stohr et al., 1999; Sutton et al., 1997; Terman et al., 1986; Terman and Liebeskind, 1986). Conversely, the effects of opiates on different components of the stress axis can impact on individual responsivity to stressors and potentially predispose individuals to stress-related psychiatric disorders (Burnett et al., 1999; Calogero et al., 1996; Carey et al., 2009; Price et al., 2004; Yamauchi et al., 1997). Because these interactions have potentially widespread clinical consequences, it is important to identify substrates of the stress response and endogenous opioid systems that interact and the specific points at which stress circuits and endogenous opioid systems intersect.

I. The LC as a key nucleus where stress and opioids interact

While it is known that interactions of stress and opiate substrates occur in various brain regions that may play a role in drug dependence and withdrawal (Houshyar et al., 2003; Maj et al., 2003; McNally and Akil, 2002), one site at which opiates and stress substrates may interact to have global effects on behavior is within the LC, the major brain norepinephrine (NE)-containing nucleus. The LC is targeted by several endogenous opioidergic peptides (Kreibich et al., 2008; Reyes et al., 2009; Reyes et al., 2008; Reyes et al., 2006; Reyes et al., 2007b; Tjoumakaris et al., 2003; Van Bockstaele et al., 1995; Van Bockstaele et al., 1996d), stress-related peptides including corticotropin releasing factor (CRF) (Valentino et al., 1992; Valentino et al., 2001; Van Bockstaele et al., 1996e; Van Bockstaele et al., 1998b; Van Bockstaele et al., 1999c) excitatory amino acids (Barr and Van Bockstaele, 2005; Kreibich et al., 2008) and orexin (Baldo et al., 2003; Koob et al., 2008) (Fig. 1). The LC receives afferents from multiple brain nuclei including the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (Van Bockstaele et al., 1999b), the central nucleus of the amygdala (CNA) (Van Bockstaele et al., 1996a), the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (Reyes et al., 2005), the nucleus of the solitary tract (Van Bockstaele et al., 1999a), the nucleus paragigantocellularis (Van Bockstaele et al., 1998a) and the nucleus prepositus hypoglossi (Aston-Jones et al., 1986). In addition, the LC has been implicated in both the stress response (Valentino and Foote, 1987; Valentino and Foote, 1988; Valentino et al., 1993) and opiate actions (Kreibich et al., 2008; Nestler et al., 1994; Nestler et al., 1999; Reyes et al., 2009; Reyes et al., 2008; Reyes et al., 2007a). Chronic stress (Cuadra et al., 1999; Curtis et al., 1995; Curtis et al., 1999), chronic CRF (Conti and Foote, 1995; Conti and Foote, 1996) and chronic exposure to exogenous opiates (Aghajanian, 1978; Duman et al., 1988; Fiorillo and Williams, 1996; Valentino and Wehby, 1989) have all been shown to induce changes in LC plasticity.

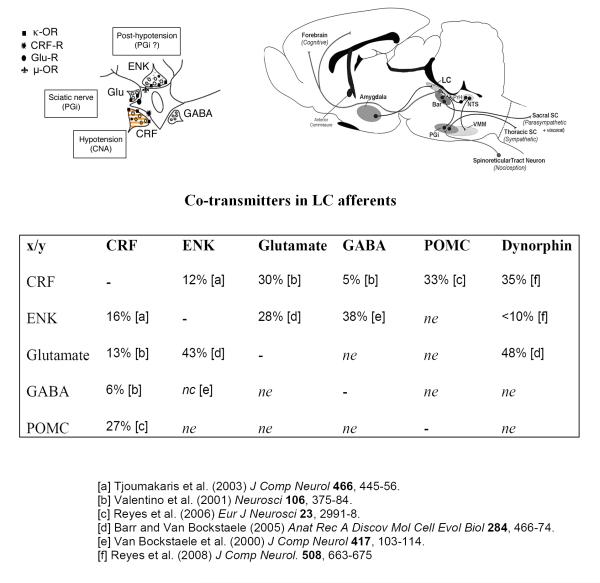

Figure 1.

Our previous studies indicate that NE activity is regulated via distinct CRF and ENK afferents targeting postsynaptically distributed CRF and μ-opioid receptors (μ-OR). The circuitry that links DYN to the LC-NE system and the conditions that engage this circuitry are steadily emerging (see text). Our working model now includes presynaptic modulation of NE activity via dynorphin-κ-OR regulation of afferent inputs that is posited to differentially affect behavior. Left schematic: Schematic diagram of an LC neuron containing μ-OR (symbol: fleur de lis), CRF-R (symbol: ink spot) and glutamate receptors (Glu-R, symbol: circle) targeted by axon terminals containing CRF, ENK, Glu or GABA. Anatomical studies support the localization of κ-OR on terminals containing glutamate, CRF and dynorphin. Right schematic: Schematic depicting selected afferents to the LC that are known to differentially modulate LC activity. CRF afferents from the amygdala are engaged to increase LC neuronal activity following hypotensive stress. Upon termination of the stress, opioid modulation of LC neurons (most likely arising from medullary sources) results in inhibition for a period of time, an effect that is completely blocked by microinfusion of naloxone. Glutamatergic afferents from the nucleus paragigantocellularis (PGi) convey sciatic nerve stimulation that is completely abolished by excitatory amino acid antagonists. Both stimuli are temporally correlated with, and necessary for, cortical EEG activation via LC efferent projections to forebrain structures. Table summarizing percentages of co-transmitters in LC afferents. Percentages are shown with respect to total number of profiles for neurotransmitters in the vertical column (e.g., ENK/total CRF sampled = 12%). Abbreviations: nc: not counted; ne: not examined

II. Anatomical and physiological attributes of the LC

The anatomical and physiological characteristics of the LC-NE system have been reviewed in detail (Aston-Jones et al., 1984; Aston-Jones et al., 1991b; Berridge and Waterhouse, 2003; Foote et al., 1983) and are only briefly summarized here. The LC is a compact, homogenous nucleus that innervates the entire neuraxis through a divergent efferent system. Single LC neurons collateralize to distant and functionally diverse brain regions. It is the sole source of NE in many forebrain regions that have been implicated in cognition (e.g., cortex and hippocampus). LC neurons are spontaneously active and discharge in a synchronous manner that is linked to oscillations in membrane potential (Aston-Jones and Bloom, 1981b; Aston-Jones et al., 1991a; Ishimatsu and Williams, 1996). In addition to their synchronous spontaneous activity, LC neurons are homogeneous in their polymodal response to stimuli (Aston-Jones and Bloom, 1981a; Foote et al., 1980). Coupled with a highly divergent, collateralized efferent system, this synchronous activity provides a mechanism for global NE release throughout the neuraxis in response to stimuli.

Tonic LC activity co-varies with behavioral and electroencephalographic (EEG) indices of arousal, such that activity is highest in the awake state, lower during slow wave sleep and silent during REM sleep (Aston-Jones and Bloom, 1981b). LC neurons respond phasically to environmental stimuli of many modalities and phasic activity is associated with enhanced NE release in target regions (Berridge and Abercrombie, 1999; Florin-Lechner et al., 1996). Excitatory amino acid afferents have been demonstrated to mediate phasic activation of LC neurons by certain somatosensory and auditory stimuli (Ennis et al., 1992). Certain physiological stimuli produce a more tonic activation of LC neurons and the stress neurohormone, CRF has been implicated in these responses (Kosoyan et al., 2005; Lechner et al., 1997; Valentino et al., 1991). Regardless of the stimulus, LC activation is sufficient to activate forebrain (e.g., cortex and hippocampus) EEG and selective LC inhibition has the opposite effect (Berridge and Foote, 1991; Berridge et al., 1993; Curtis et al., 1997; De Sarro et al., 1987; de Sarro et al., 1988; De Sarro et al., 1992; Page et al., 1992; Page et al., 1993). Moreover stress-elicited LC activation has been shown to be necessary for EEG activation by some stressors (Page et al., 1993). Thus, the LC-NE system provides a mechanism by which external and internal stimuli elicit arousal.

In addition to arousal, the LC-NE system is hypothesized to facilitate shifts in the mode of attention, from focused to scanning. This is partly based on LC recordings in monkeys during a focused attention task (Aston-Jones et al., 1999; Rajkowski et al., 1994; Usher et al., 1999). Low tonic LC discharge rate, coupled with low phasic responses to sensory stimuli, are associated with inattention, drowsiness and poor task performance. In contrast, relatively higher tonic LC discharge rates are coupled with robust phasic responses to stimuli and associated with focused attention and optimal behavioral performance. However, increases in tonic LC discharge that exceed the optimal rate are associated with a decrement in attention to the target stimuli and poor task performance. During this time, monkeys attend to task-irrelevant stimuli. In spite of the increase in tonic discharge at this time, phasic responses to stimuli are blunted. This has led to a hypothesized inverted U-shaped relationship between tonic LC activity and focused attention. Importantly, moderate tonic LC activity and robust phasic activity are associated with focused attention, whereas high tonic activity and blunted phasic activity are associated with scanning or labile attention. We will consider the different modes of LC activity as they relate to CRF and μ-opioid agonists below.

III. Opioids and the LC

Afferent regulation of the LC by endogenous opioids is well-supported by anatomical evidence and electrophysiological effects of opiates on LC activity. Enkephalin (ENK) densely innervates the nuclear core of the LC and is robust in peri-coerulear dendritic zones, particularly at the level of the rostral LC (Van Bockstaele et al., 1995; Van Bockstaele and Chan, 1997; Van Bockstaele et al., 1996c; Van Bockstaele et al., 1996d). Small molecule co-transmitters in ENK-containing axon terminals include glutamate (Barr and Van Bockstaele, 2005; Van Bockstaele et al., 2000) and gamma-amino butyric acid (GABA) (Valentino et al., 2001) (Fig. 1).

The three classes of opioid receptors, mu (μ), delta (δ) and kappa (κ) are prominently distributed within the LC (Elde and Hokfelt, 1993; Van Bockstaele et al., 1995; Van Bockstaele et al., 1996b; Van Bockstaele et al., 1996c). The μ-opioid receptor (μ-OR) is prominently localized postsynaptically within noradrenergic somatodendritic processes (Van Bockstaele et al., 1996b; Van Bockstaele et al., 1996c) while δ-OR and κ-OR are mainly localized to axon terminals (Kreibich et al., 2008; Reyes et al., 2009; van Bockstaele et al., 1997) suggesting that δ-OR and κ-OR may play important roles in presynaptic modulation of neurotransmitter release (see below).

Two brainstem regions that have been shown to provide the major sources of opioid innervation to the LC include the nucleus paragigantocellularis (PGi) in the rostral ventrolateral medulla and the nucleus prepositus hypoglossus (PrH) in the dorsomedial rostral medulla (Aston-Jones et al., 1986; Aston-Jones et al., 1991b; Drolet et al., 1992).

Potent inhibitory effects of μ-OR activation on LC neurons in vivo and in vitro have been well documented (Aghajanian and Wang, 1987; Korf et al., 1974; Valentino and Wehby, 1988b; Williams et al., 1984; Williams et al., 1982). However, the impact of endogenous opioids on the LC system remained unknown until we provided evidence that endogenous opioids are released within the LC following the termination of hypotensive stress to produce a robust inhibition (Curtis et al., 2001). Thus, during hypotensive stress, LC neurons are activated and this is temporally correlated with, and necessary for, cortical EEG activation (Page et al., 1993; Valentino et al., 1991). Pharmacological analysis revealed that this activation is mediated by CRF release in the LC (see below). Upon stress termination, LC neurons are inhibited for a period of time and this effect is completely blocked by microinfusion of naloxone into the LC (Curtis et al., 2001). In the presence of naloxone, LC neuronal activity takes longer to return to baseline, suggesting that endogenous opioid release in the LC helps to restore basal activity. This presumably protects against adverse consequences of continued activation of the system (e.g., hyperarousal). Thus, opioid-mediated post-stress inhibition of the LC-NE system may serve as a counterregulatory mechanism to balance or limit this cognitive limb of the stress response, much in the same vein that glucocorticoids counter-regulate the hypothalamo-pituitary limb.

IV. Corticotropin-releasing factor and the LC

CRF, the neurohormone that initiates pituitary adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) release during stress (Vale et al., 1981), also serves as a neuromodulator to activate the LC-NE system in response to certain challenges (Valentino and Van Bockstaele, 2005). CRF axon terminals synapse with LC dendrites and direct administration of CRF onto LC neurons in vivo and in vitro produces a long-lasting tonic increase in LC discharge rate, (Curtis et al., 1997; Jedema and Grace, 2004; Van Bockstaele et al., 1996e). This is associated with elevated cortical NE efflux (Curtis et al., 1997; Page and Abercrombie, 1999), and cortical EEG activation (Curtis et al., 1997). Our laboratory demonstrated that endogenous CRF is released within the LC to activate this system during hypotensive challenge, providing the first evidence for a neurotransmitter role of CRF in a particular nucleus (Curtis et al., 2001; Page et al., 1993; Valentino et al., 1991). Thus, CRF antagonists selectively and completely prevented LC activation by hypotensive challenge when microinfused into the LC. Moreover, the IC 50 for two different CRF antagonists in antagonizing CRF were similar to their IC 50s for preventing an equieffective activation by hypotensive stress, underscoring the involvement of a common receptor (Curtis et al., 1994). CRF-elicited LC activation was necessary for cortical EEG desynchronization that was associated with the stress, suggesting that LC activation is necessary for arousal associated with this stressor (Page et al., 1993). In addition to tonically increasing LC discharge rate, CRF blunts LC phasic responses to somatosensory and auditory stimuli (Valentino and Foote, 1987; Valentino and Foote, 1988). This blunting effect is also observed during hypotensive stress which engages endogenous CRF release in the LC (Valentino and Wehby, 1988a). Increased tonic LC activity accompanied by decreased phasic responses to discrete stimuli (as occurs with CRF) may facilitate a shift from focused to scanning or labile attention. This may be adaptive in the acute response to a stressor.

In studies using lesions and functional neuroanatomy, the CNA was identified as the source of CRF that activates the LC during hypotension (Rouzade-Dominguez et al., 2001). Lesions of the CNA, but not Barrington’s nucleus (Rouzade-Dominguez et al., 2001) or the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (other sources of CRF afferents to the LC) greatly attenuated LC activation by hypotensive challenge. Additionally, hypotensive challenge induced phospho-cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) response element-binding proteins (pCREB) in CNA-CRF neurons that were retrogradely labeled from the LC, but not in other sources of CRF afferents to the LC (Curtis et al., 2002). Interestingly, our anatomical studies argue against the CNA as a source of ENK in the LC, consistent with other evidence that CRF mediating stress-induced LC activation and endogenous opioids mediating post-stress LC inhibition originate from different sources (Tjoumakaris et al., 2003).

V. Co-regulation of the LC-NE system by CRF and opioids

Together, the electrophysiological studies discussed above suggested that activity of the LC-NE system is co-regulated by CRF and endogenous opioids, such that the onset of stress releases CRF within the LC to activate this system with the consequence of increased arousal and shift from focused to scanning attention. The termination of stress engages endogenous opioids to inhibit the system and return activity back to baseline (Curtis et al., 2001; Valentino et al., 1991). In addition to the conceptual relevance of these findings, this study indicated that hypotensive challenge can be used as a tool to probe release of either endogenous CRF or endogenous opioids in the LC.

The finding that CRF and opioids regulate the activity of the LC-NE system during stress in an opposite manner is further supported by anatomical data showing prominent co-existence of CRF and μ-ORs in LC neurons (Reyes et al., 2007a). The co-localization of CRF receptors and μ-ORs in noradrenergic somatodendritic processes suggests that these two receptors may function principally in a postsynaptic fashion. CRF and opioid peptides may be co-released from the same axon terminals to affect LC neuronal activity or released from separate axon terminals that converge onto common LC dendrites (Tjoumakaris et al., 2003). The integrity of the CRF-opioid balance in the LC is important and particularly relevant to opiate-seeking behavior for individuals that are chronically taking opiates (see below). Thus, the strategic co-localization of CRFr and μ-OR in LC dendrites may underlie continued opiate-seeking behavior in an effort to attenuate the hypersensitivity of the LC-NE system to stress.

VI. Implications of a CRF/opioid imbalance in the LC

Given the opposing regulation of the LC-NE system by CRF and opioids, upsetting the CRF:opioid balance in the LC could influence the stress-sensitivity of this system and enhance vulnerability to stress or conversely, vulnerability to opiate abuse. Consistent with this, chronic morphine administration sensitized LC neurons to CRF (Xu et al., 2004). LC sensitization to CRF was expressed as increased sensitivity of the neurons to hypotensive stress. Importantly, this neuronal plasticity translated to a change in the behavioral repertoire of the animal in response to stress. Thus, when exposed to swim stress, morphine-treated rats were unusual in that they exhibited a strikingly higher incidence of climbing (Xu et al., 2004), a behavior that has been attributed to central NE activation in this model (Detke et al., 1995). These findings predict that chronic opiate use, whether as a result of abuse or clinical use, predisposes individuals to certain stress-related pathology. In addition to increasing vulnerability to stress-related pathology, opiate-induced sensitization of the LC-NE system may facilitate the maintenance of opiate use in an effort to counteract the hypersensitivity of the LC-NE system.

VII. Potential mechanisms underlying stress/opioid plasticity of LC neurons

Chronic opiate use results in tolerance at the level of the LC that is expressed as a decreased ability of opiates to hyperpolarize and inhibit LC neurons (Aghajanian, 1978; Christie et al., 1987; Rasmussen and Krystal, 1990). At an intracellular level, repeated opiate administration mimics the effects of chronic stress in increasing expression of components of the cAMP pathway (Guitart and Nestler, 1993; Nestler, 1993; Nestler et al., 1994; Nestler et al., 1999; Nestler et al., 1993; Nestler and Tallman, 1988). The site of opiate-induced plasticity appears to be downstream of adenyl cyclase because the dose–response curve for LC activation by 8-Br-cAMP was also shifted in rats chronically administered morphine (Kogan et al., 1992). One site of opioid regulation along this pathway is at the level of cAMP-dependent protein kinase, which has been demonstrated to be elevated in the LC by chronic morphine treatment (Nestler and Tallman, 1988). Assuming that CRF activation of the LC requires the same intracellular cascade, the effects of CRF and stressors that release CRF into the LC would be predicted to be enhanced in opiate-tolerant subjects.

Like chronic stress, the development of opiate tolerance results in an imbalance of influence on the LC–NE system in favor of CRF-induced activation. Repeated opiate use could predispose to stress-related disorders that have been attributed to the LC–NE system. Examples of these are depression, anxiety, or post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms. In support of this is a high co-morbidity of psychiatric disorders in opiate dependence (Cottler et al., 1992; Markou et al., 1998). The need to reestablish a balance between the influences of these neuropeptides on the LC–NE system may play a role in the maintenance of self-administration of opiates. However, the clinical impact of a CRF–opioid imbalance goes beyond opiate abuse and extends to individuals who chronically use opiates for medical disorders.

Dynorphin and κ-ORs: Presynaptic modulator of LC activity

As described above, the most well studied opioid-mediated effect on LC neurons is the μ-OR mediated-inhibition characterized by a decrease in spontaneous discharge in vivo and hyperpolarization at the cellular level in vitro. Given the prominent expression of μ-OR in the LC and innervation by ENK peptides that can elicit this μ-OR-mediated response, our original working hypothesis proposed that the LC was co-regulated by CRF excitation during stress and μ-OR mediated inhibition following stress. More recently, our model has expanded to include an additional layer of regulation mediated by κ-OR activation. Evidence suggests that κ-OR regulation of the LC is distinct from that mediated by CRF or μ-ORs in that it appears to involve presynaptic regulation of afferent input.

The dynorphin (DYN)/κ-OR system has been implicated in the mediation of stress and vulnerability to drug abuse. For example, stress, which promotes relapse and can facilitate place preference for drugs of abuse, increases prodynorphin gene expression in the limbic system (Shirayama et al., 2004). Genetic deletion of prodynorphin or pharmacological antagonism of kappa receptors prevented stress-induced preference, implicating the DYN/κ-OR system in stress-induced facilitation of drug abuse (Shirayama et al., 2004). Additionally, κ-OR antagonists prevent stress-elicited behaviors that are endpoints of depression such as immobility in the forced swim test and passive behavior in learned helplessness (Mague et al., 2003; McLaughlin et al., 2003; Shirayama et al., 2004). Our recent evidence for localization of DYN in the LC region (Reyes et al., 2007b) and co-localization of DYN with CRF in axon terminals in the LC (Reyes et al., 2008) implicate the LC as one site at which DYN modulates stress responses and the consequences of stress on behavior. Furthermore, the prominent localization of κ-ORs in axon terminals in the LC that contain CRF or the vesicular glutamate transporter, indicate that κ-ORs are poised to presynaptically inhibit diverse afferent signaling to the LC. This is a novel and potentially powerful means of regulating the LC-NE system that can impact on forebrain processing of stimuli and the organization of behavioral strategies in response to environmental stimuli. As described below, our results implicate κ-ORs as a novel target for alleviating symptoms of opiate withdrawal, stress-related disorders or disorders characterized by abnormal sensory responses, such as autism.

I. Anatomical considerations

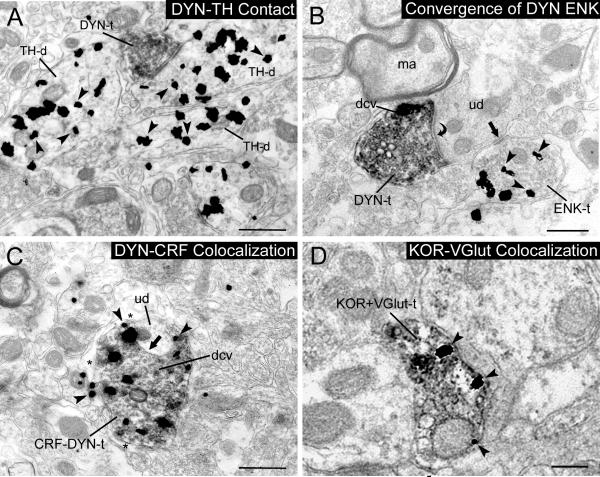

DYN afferents prominently target the LC (Reyes et al., 2007b) and co-exist with CRF in common axon terminals (Fig. 2). By electron microscopy, we have reported that DYN directly targets noradrenergic somatodendritic processes (Reyes et al., 2007b) and that these form primarily asymmetric (excitatory) type synapses (Fig. 3A). When combined with immunogold-silver labeling for CRF, single axon terminals were found to contain both peptides (Fig. 3C) (Reyes et al., 2008). Our data also indicate that the endogenous opioids, DYN and ENK, more frequently converge on common postsynaptic targets (Fig. 3B) rather than being co-localized, a finding that is similar to the synaptic organization of CRF and ENK afferents in the LC (Tjoumakaris et al., 2003).

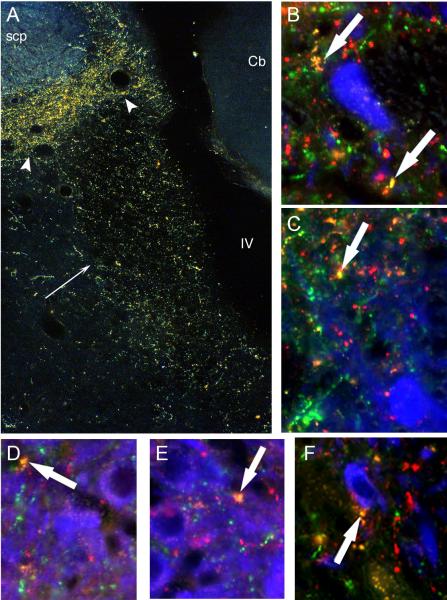

Figure 2.

A. Darkfield photomicrograph showing immunoperoxidase labeling of DYN in the core of the LC (straight black arrow) and peri-LC area (arrowheads). Cb: cerebellum; IV: 4th ventricle; scp: superior cerebellar peduncle. B-F. Processes exhibiting DYN (red), CRF (green) or both DYN/CRF (yellow) overlap TH neurons (blue) in the LC. White arrows indicate DYN/CRF processes in close proximity to TH somatodendritic profiles. Panels D and E are taken through the core of the LC while panels B, C and F are in the peri-LC. Scale bar = 250 μm.

Figure 3.

A. Immunoperoxidase labeled DYN axon terminal (DYN-t) forms an asymmetric-type (excitatory) synapse with a dendrite containing TH (TH-d). B. Immunoperoxidase labeling for DYN (that is particularly enriched in dense core vesicles, dcv) in an axon terminal (DYN-t) that forms a synapse (curved arrow) with an unlabeled dendrite (ud) that receives convergent input from an axon terminal containing gold-silver labeling for ENK. C. An axon terminal contains immunogold-silver labeling for CRF (arrowheads) and immunoperoxidase labeling for DYN. CRF-DYN-t contains several dense core vesicles (dcv) and forms a synapse (black arrow) with an unlabeled dendrite (ud). D. An axon terminal containing immunoperoxidase labeling for VGLUT also exhibits immunogold-silver labeling for κ-OR in the LC. Scale bars: 0.5 μm.

Previous anatomical studies have shown that the CNA is enriched with DYN cell bodies (Khachaturian et al., 1982; Watson et al., 1983). Likewise, retrograde and anterograde tract-tracing studies revealed that the CNA is the source of the CRF innervation in the LC (Sakanaka et al., 1986; Van Bockstaele et al., 1998b). Accordingly, the CNA is considered a potential source of DYN/CRF terminals in the LC. We have demonstrated that unilateral lesions of the CNA substantially decreased CRF-immunolabeling in the LC (Reyes et al., 2008), consistent with our previous reports (Tjoumakaris et al., 2003; Van Bockstaele et al., 1998b) as well as others (Sakanaka et al., 1986). Evidence of reduced DYN innervation in the same cases indicates that DYN innervation of this region and the dually labeled axon terminals are derived from common limbic sources. Our recent studies show that a common neuronal population in the CNA serves as a source for both DYN and CRF projecting to the LC (Van Bockstaele et al., 2009). Additional sources of potential afferent inputs to the LC that colocalize DYN and CRF include the bed nucleus of stria terminalis, the nucleus of the solitary tract and hypothalamic regions including the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (Reyes et al., 2005; Van Bockstaele et al., 1999b; Van Bockstaele et al., 1999b) and these remain to be investigated.

Anatomical studies revealed some evidence of modest co-localization of DYN- and ENK-labeled axon terminals in the LC (Reyes et al., 2008). However, the cellular interactions between individual DYN- and ENK-labeled axon terminals were more frequently convergence of separately labeled afferents on common LC dendrites (Fig. 3B), and also presynaptic interactions. This suggests that co-release of DYN and ENK in the LC by distinct afferents can impact common targets. While CNA provides CRF innervation to the LC (Reyes et al., 2008), it does not provide robust ENK innervation to the LC (Tjoumakaris et al., 2003). Therefore, while the CNA serves as a source of DYN in the LC, it is not the source of axon terminals that co-localize DYN and ENK. A possible mechanism by which a common stimulus could result in DYN and ENK release to impact the same LC neuron is via parallel stimulation of separate populations of DYN and ENK neurons that converge on common targets in the noradrenergic LC. It has been established that the PGi provides a robust enkephalinergic projection to the core and peri-coerulear dendritic area (Drolet et al., 1992). Hence, it is likely that two important autonomic brain regions, the CNA and the PGi, converge on the LC to influence the activity of noradrenergic LC neurons under certain conditions.

As discussed above, κ-OR mRNA and protein have been identified in the LC (DePaoli et al., 1994; Mansour et al., 1994) and anatomical studies have shown that this receptor subtype is prominently distributed presynaptically in LC afferents (Kreibich et al., 2008; Reyes et al., 2009) (Fig. 3D). Presynaptic effects of κ-OR activation have been described in other brain regions (Ackley et al., 2001; Bie and Pan, 2003; Drake et al., 1997; Hjelmstad and Fields, 2001; Ogura and Kita, 2000; Simmons and Chavkin, 1996; Svingos et al., 2001; Svingos and Colago, 2002; Svingos et al., 1999; Wang et al., 2009; Weisskopf et al., 1993). In many of these regions, glutamate, glycine, and GABA neurotransmission were targets of κ-OR-mediated presynaptic effects. Indeed, κ-ORs have been identified in glutamatergic afferents to the LC (Barr and Van Bockstaele, 2005) (Fig. 3D) as well as in DYN (Reyes et al., 2009) and CRF- containing (Kreibich et al., 2008) axon terminals. Thus, κ-ORs can broadly impact LC function through presynaptic modulation of diverse neurotransmitters.

II. Effect of the κ-OR-agonists on LC activity

Our findings of co-localization of DYN with vesicular glutamate transporters (Barr and Van Bockstaele, 2005) or CRF in axon terminals in the LC suggested that this unique endogenous opioid system contributes to the regulation the LC-NE system during stress (Reyes et al., 2008). In support of this, the κ-OR agonists, DYN A or U50488, microinfused directly into the LC had effects on single unit LC activity in halothane-anesthetized rats that were distinct from the μ-agonists, morphine and DAMGO. Without altering LC spontaneous discharge, κ-OR-agonists attenuated LC activation by sciatic nerve stimulation, a sensory-evoked response mediated by excitatory amino acid neurotransmission in the LC (Kreibich et al., 2008). Similar effects were seen in unanesthetized rats where intracerebroventricular administration of U50488 decreased LC activation by auditory stimuli with no effect on spontaneous discharge (Kreibich et al., 2008). These in vivo findings are consistent with in vitro studies in LC slice preparations demonstrating that κ-OR activation depresses excitatory synaptic potentials without affecting passive membrane properties or voltage-sensitive potassium currents (Pinnock, 1992) and suggest that this is a presynaptic effect on glutamate release. The co-localization of DYN with vesicular glutamate transporters in axon terminals within the LC (Barr and Van Bockstaele, 2005) is consistent with presynaptic modulation of glutamate release. Interestingly, LC neuronal activation during opiate withdrawal is mediated in part by excitatory amino acid inputs to the LC (Han et al., 2006; Maldonado et al., 1992; Rasmussen et al., 1990; Redmond and Huang, 1982) and this was also attenuated by U50488 microinfusion into the LC. This is particularly relevant for opiate addiction because activation of the LC-norepinephrine system during opiate withdrawal is thought to underlie some of the aversive aspects of opiate withdrawal and contribute to negative reinforcing properties of morphine. These results suggest that this aspect of withdrawal may be attenuated by engaging kappa opiate receptors in the LC. Nevertheless, it has been shown that κ-OR agonists such as U50-488 cause place aversion in animals (Land et al., 2008; Shippenberg and Herz 1986).

To determine whether κ-OR could modulate CRF afferents to LC, the effects of U50488 on LC activation elicited by hypotensive stress were examined. Pretreatment with U50488 prevented LC activation by hypotensive challenge, a stressor known to selectively engage CRF afferents to the LC (Kreibich et al., 2008). These data underscore the general nature of presynaptic inhibition by κ-OR in the LC.

III. Implications for κ-OR-mediated presynaptic inhibition for LC function

Based on the aforementioned studies, κ-OR modulation of LC phasic sensory responses should translate to diminished reactions to sensory stimuli and decreased ability of these stimuli to alter the course of ongoing behaviors. The absence of an effect on tonic activity implies that this would occur in the absence of alterations in general arousal. Interestingly, kappa agonists have been shown to disrupt performance in the 5-choice serial reaction time task by increasing number of omissions and latency to respond (Paine et al., 2007; Shannon et al., 2007). These effects could also be expressed as a blunting of affect. Consistent with this, the dynorphin-κ-OR system has been implicated in depression and supports the notion that κ-OR antagonists may be useful antidepressants (Mague et al., 2003; McLaughlin et al., 2006; McLaughlin et al., 2003; Pliakas et al., 2001; Shirayama et al., 2004).

In other clinical conditions that are characterized by excessive responses to sensory stimuli, the ability of κ-OR agonists to attenuate responses without altering the general state of arousal might be a useful therapeutic approach. Examples include attentional disorders, where sensory stimuli are significant distracters, or autism, which can present as unusually heightened sensory responses (Gomot et al., 2002; Tomchek and Dunn, 2007). The demonstration that κ-OR activation in the LC also attenuates the excitation of LC neurons by opiate withdrawal is consistent with presynaptic inhibition of glutamate afferents that mediate the effect (Han et al., 2006; Maldonado et al., 1992; Rasmussen and Krystal, 1990; Redmond Jr, 1982) and suggests that κ-OR agonists might be useful in alleviating symptoms of opiate withdrawal (Akaoka and Aston-Jones, 1991; Rasmussen and Aghajanian, 1989; Rasmussen et al., 1991).

Conclusions

LC neurons, with their widely distributed network of axons, promote cognitive and behavioral limbs of the stress response through changes in their discharge rate and pattern in tune with dynamic environments. The mode of LC activity is finely tuned by a convergence of afferents, particularly excitatory amino acids, CRF and endogenous opioids. Aston-Jones and colleagues proposed a model whereby tonic and phasic modes of LC discharge facilitate distinct and exclusive processes (Aston-Jones and Cohen, 2005). In this model, phasic activity facilitates ongoing behavior and optimizes performance in tasks requiring selective attention, whereas high tonic activity promotes attention to extraneous stimuli, disengagement from ongoing tasks and searching for alternate tasks when present behavior is not optimal. By biasing LC activity towards a particular discharge mode, EAA, opioid and CRF afferents can shape predominant behavioral strategies in these environments. EAA afferents would facilitate selective attention and optimal performance of ongoing tasks through enhancement of phasic discharge. CRF shifts LC activity towards a high tonic and lower phasic mode, an effect associated with hyperarousal, disengagement from ongoing behavior and scanning of environmental stimuli (Valentino and Foote, 1987; Valentino and Foote, 1988). In contrast, moderate levels of endogenous opioids acting at μ-OR receptors bias activity toward the phasic mode, by selectively decreasing tonic activity (Valentino and Foote, 1988). In opposition to CRF, engaging μ-OR should promote focused attention and maintenance of ongoing behavior. Consequences of k-OR presynaptic inhibition contrast all of these and suggest a novel level of regulation that takes the LC “offline”. By decreasing the ability of stimuli to phasically activate LC neurons, ongoing behavior and performance in tasks requiring focused attention will be disrupted. At the same time, by not increasing tonic discharge, the impetus to seek alternate strategies will not be promoted. Because spontaneous activity is unaffected, this unresponsive state should be present in the absence of sedation.

In summary, elucidating the circuitry by which particular afferents target LC neurons to influence its activity that may ultimately influence behavioral repertoires in an attempt to adapt to specific situations or environments is important in understanding and formulating therapeutic approaches in the treatment of diverse stress-related psychiatric disorders as well as relapse and vulnerability to opiate abuse.

List of abbreviations

- ACTH

adrenocorticotropic hormone

- cAMP

cyclic adenosine monophosphate

- CNA

central nucleus of the amygdala

- CRF

corticotropin releasing factor

- δ-OR

δ-opioid receptor

- DYN

dynorphin

- EEG

electroencephalographic

- ENK

enkephalin

- GABA

gamma-amino butyric acid

- κ-OR

κ-opioid receptor

- LC

locus coeruleus

- μ-OR

μ-opioid receptor

- NE

norepinephrine

- PGI

nucleus paragigantocellularis

- PrH

nucleus prepositus hypoglossus

- pCREB

phospho-cAMP response element-binding proteins

References

- Ackley MA, Hurley RW, Virnich DE, Hammond DL. A cellular mechanism for the antinociceptive effect of a kappa opioid receptor agonist. Pain. 2001;91:377–388. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00464-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aghajanian GK. Tolerance of locus coeruleus neurones to morphine and suppression of withdrawal response by clonidine. Nature. 1978;276:186–188. doi: 10.1038/276186a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aghajanian GK, Wang YY. Common alpha 2- and opiate effector mechanisms in the locus coeruleus: intracellular studies in brain slices. Neuropharmacology. 1987;26:793–799. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(87)90054-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akaoka H, Aston-Jones G. Opiate withdrawal-induced hyperactivity of locus coeruleus neurons is substantially mediated by augmented excitatory amino acid input. J. Neurosci. 1991;11:3830–3839. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-12-03830.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aston-Jones G, Bloom FE. Activity of norepinephrine-containing locus coeruleus neurons in behaving rats anticipates fluctuations in the sleep-waking cycle. J. Neurosci. 1981a;1:876–886. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.01-08-00876.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aston-Jones G, Bloom FE. Norepinephrine-containing locus coeruleus neurons in behaving rats exhibit pronounced responses to non-noxious environmental stimuli. J. Neurosci. 1981b;1:887–900. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.01-08-00887.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aston-Jones G, Chiang C, Alexinsky T. Discharge of noradrenergic locus coeruleus neurons in behaving rats and monkeys suggests a role in vigilance. Prog. Brain Res. 1991a;88:501–520. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)63830-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aston-Jones G, Cohen JD. An integrative theory of locus coeruleus-norepinephrine function: adaptive gain and optimal performance. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2005;28:403–450. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.061604.135709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aston-Jones G, Ennis M, Pieribone VA, Nickell WT, Shipley MT. The brain nucleus locus coeruleus: restricted afferent control of a broad efferent network. Science. 1986;234:734–737. doi: 10.1126/science.3775363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aston-Jones G, Foote SL, Bloom FE. Anatomy and physiology of locus coeruleus neurons: functional implications. In: Ziegler M, Lake CR, editors. Norepinephrine (Frontiers of Clinical Neuroscience) vol. 2. Williams and Wilkins; Baltimore: 1984. pp. 92–116. [Google Scholar]

- Aston-Jones G, Rajkowski J, Cohen J. Role of locus coeruleus in attention and behavioral flexibility. Biol. Psychiatry. 1999;46:1309–1320. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00140-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aston-Jones G, Shipley MT, Chouvet G, Ennis M, Van Bockstaele EJ, Pieribone V, Shiekhattar R, Akaoka H, Drolet G, Astier B, et al. Afferent regulation of locus coeruleus neurons: anatomy, physiology and pharmacology. Prog. Brain Res. 1991b;88:47–75. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)63799-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldo BA, Daniel RA, Berridge CW, Kelley AE. Overlapping distributions of orexin/hypocretin- and dopamine-beta-hydroxylase immunoreactive fibers in rat brain regions mediating arousal, motivation, and stress. J. Comp. Neurol. 2003;464:220–237. doi: 10.1002/cne.10783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr J, Van Bockstaele EJ. Vesicular glutamate transporter-1 colocalizes with endogenous opioid peptides in axon terminals of the rat locus coeruleus. Anat. Rec. A Discov. Mol. Cell Evol. Biol. 2005;284:466–474. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.20184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedek G, Szikszay M. Sensitization or tolerance to morphine effects after repeated stresses. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 1985;9:369–380. doi: 10.1016/0278-5846(85)90189-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge CW, Abercrombie ED. Relationship between locus coeruleus discharge rates and rates of norepinephrine release within neocortex as assessed by in vivo microdialysis. Neuroscience. 1999;93:1263–1270. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00276-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge CW, Foote SL. Effects of locus coeruleus activation on electroencephalographic activity in neocortex and hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 1991;11:3135–3145. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-10-03135.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge CW, Page ME, Valentino RJ, Foote SL. Effects of locus coeruleus inactivation on electroencephalographic activity in neocortex and hippocampus. Neuroscience. 1993;55:381–393. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90507-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge CW, Waterhouse BD. The locus coeruleus-noradrenergic system: modulation of behavioral state and state-dependent cognitive processes. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 2003;42:33–84. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(03)00143-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bie B, Pan ZZ. Presynaptic mechanism for anti-analgesic and anti-hyperalgesic actions of kappa-opioid receptors. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:7262–7268. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-19-07262.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett FE, Scott LV, Weaver MG, Medbak SH, Dinan TG. The effect of naloxone on adrenocorticotropin and cortisol release: evidence for a reduced response in depression. J. Affect Disord. 1999;53:263–268. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(98)00127-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calogero AE, Scaccianoce S, Burrello N, Nicolai R, Muscolo LA, Kling MA, Angelucci L, D’Agata R. The kappa-opioid receptor agonist MR-2034 stimulates the rat hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis: studies in vivo and in vitro. J. Neuroendocrinol. 1996;8:579–585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey AN, Lyons AM, Shay CF, Dunton O, McLaughlin JP. Endogenous kappa opioid activation mediates stress-induced deficits in learning and memory. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:4293–4300. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6146-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie MJ, Chesher GB. Physical dependence on physiologically released endogenous opiates. Life Sci. 1982;30:1173–1177. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(82)90659-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie MJ, Trisdikoon P, Chesher GB. Tolerance and cross tolerance with morphine resulting from physiological release of endogenous opiates. Life Sci. 1982;31:839–845. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(82)90538-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie MJ, Williams JT, North RA. Mechanisms of tolerance to opiates in locus coeruleus neurons. NIDA Res. Monogr. 1987;78:158–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti LH, Foote SL. Effects of pretreatment with corticotropin-releasing factor on the electrophysiological responsivity of the locus coeruleus to subsequent corticotropin-releasing factor challenge. Neuroscience. 1995;69:209–219. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00222-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti LH, Foote SL. Reciprocal cross-desensitization of locus coeruleus electrophysiological responsivity to corticotropin-releasing factor and stress. Brain Res. 1996;722:19–29. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00175-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottler LB, Compton WM, 3rd, Mager D, Spitznagel EL, Janca A. Posttraumatic stress disorder among substance users from the general population. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1992;149:664–670. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.5.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuadra G, Zurita A, Lacerra C, Molina V. Chronic stress sensitizes frontal cortex dopamine release in response to a subsequent novel stressor: reversal by naloxone. Brain Res. Bull. 1999;48:303–308. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(98)00179-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis AL, Bello NT, Connally KR, Valentino RJ. Corticotropin-releasing factor neurons of the central nucleus of the amygdala mediate locus coeruleus activation by cardiovascular stress termination. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2002;14:667–682. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2002.00821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis AL, Bello NT, Valentino RJ. Evidence for functional release of endogenous opioids in the locus ceruleus during stress termination. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:RC152. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-13-j0001.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis AL, Grigoriadis DE, Page M.E,, Rivier, J., Valentino RJ. Pharmacological comparison of two corticotropin-releasing factor antagonists: in vivo and in vitro studies. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1994;268:359–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis AL, Lechner SM, Pavcovich LA, Valentino RJ. Activation of the locus coeruleus noradrenergic system by intracoerulear microinfusion of corticotropin-releasing factor: effects on discharge rate, cortical norepinephrine levels and cortical electroencephalographic activity. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1997;281:163–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis AL, Pavcovich LA, Grigoriadis DE, Valentino RJ. Previous stress alters corticotropin-releasing factor neurotransmission in the locus coeruleus. Neuroscience. 1995;65:541–550. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)00496-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis AL, Pavcovich LA, Valentino RJ. Long-term regulation of locus ceruleus sensitivity to corticotropin-releasing factor by swim stress. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1999;289:1211–1219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Sarro GB, Ascioti C, Froio F, Libri V, Nistico G. Evidence that locus coeruleus is the site where clonidine and drugs acting at alpha 1- and alpha 2-adrenoceptors affect sleep and arousal mechanisms. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1987;90:675–685. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1987.tb11220.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Sarro GB, Bagetta G, Ascioti C, Libri V, Nistico G. Microinfusion of clonidine and yohimbine into locus coeruleus alters EEG power spectrum: effects of aging and reversal by phosphatidylserine. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1988;95:1278–1286. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1988.tb11765.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Sarro GB, Fratta W, Giglio A, Nistico G. Electrocortical power spectrum changes induced by microinfusion of corticotropin-releasing factor into the locus coeruleus in rats. Funct. Neurol. 1992;7:407–412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePaoli AM, Hurley KM, Yasada K, Reisine T, Bell G. Distribution of kappa opioid receptor mRNA in adult mouse brain: an in situ hybridization histochemistry study. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 1994;5:327–335. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1994.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detke MJ, Rickels M, Lucki I. Active behaviors in the rat forced swimming test differentially produced by serotonergic and noradrenergic antidepressants. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1995;121:66–72. doi: 10.1007/BF02245592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake CT, Chavkin C, Milner TA. Kappa opioid receptor-like immunoreactivity is present in substance P-containing subcortical afferents in guinea pig dentate gyrus. Hippocampus. 1997;7:36–47. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1997)7:1<36::AID-HIPO4>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drolet G, Van Bockstaele EJ, Aston-Jones G. Robust enkephalin innervation of the locus coeruleus from the rostral medulla. J. Neurosci. 1992;12:3162–3174. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-08-03162.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duman RS, Tallman JF, Nestler EJ. Acute and chronic opiate-regulation of adenylate cyclase in brain: specific effects in locus coeruleus. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1988;246:1033–1039. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn AJ, Berridge CW. Physiological and behavioral responses to corticotropin-releasing factor administration: is CRF a mediator of anxiety or stress responses? Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 1990;15:71–100. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(90)90012-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elde R, Hokfelt T. Coexistence of opioid peptides with other neurotransmitters. In: Herz A, editor. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology, Opioids I. Springer; Berlin: 1993. pp. 585–624. [Google Scholar]

- Ennis M, Aston-Jones G, Shiekhattar R. Activation of locus coeruleus neurons by nucleus paragigantocellularis or noxious sensory stimulation is mediated by intracoerulear excitatory amino acid neurotransmission. Brain Res. 1992;598:185–195. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90182-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorillo CD, Williams JT. Opioid desensitization: interactions with G-protein-coupled receptors in the locus coeruleus. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:1479–1485. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-04-01479.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florin-Lechner SM, Druhan JP, Aston-Jones G, Valentino RJ. Enhanced norepinephrine release in prefrontal cortex with burst stimulation of the locus coeruleus. Brain Res. 1996;742:89–97. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)00967-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foote SL, Aston-Jones G, Bloom FE. Impulse activity of locus coeruleus neurons in awake rats and monkeys is a function of sensory stimulation and arousal. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1980;77:3033–3037. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.5.3033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foote SL, Bloom FE, Aston-Jones G. Nucleus locus ceruleus: new evidence of anatomical and physiological specificity. Physiol. Rev. 1983;63:844–914. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1983.63.3.844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaal L, Molnar P. Effect of vinpocetine on noradrenergic neurons in rat locus coeruleus. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1990;187:537–539. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(90)90383-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goeders NE. Stress, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, and vulnerability to drug abuse. NIDA Res. Monogr. 1998;169:83–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goeders NE. The impact of stress on addiction. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2003;13:435–441. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2003.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomot M, Giard MH, Adrien JL, Barthelemy C, Bruneau N. Hypersensitivity to acoustic change in children with autism: electrophysiological evidence of left frontal cortex dysfunctioning. Psychophysiology. 2002;39:577–584. doi: 10.1017.S0048577202394058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guitart X, Nestler EJ. Second messenger and protein phosphorylation mechanisms underlying opiate addiction: studies in the rat locus coeruleus. Neurochem. Res. 1993;18:5–13. doi: 10.1007/BF00966918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han MH, Bolanos CA, Green TA, Olson VG, Neve RL, Liu RJ, Aghajanian GK, Nestler EJ. Role of cAMP response element-binding protein in the rat locus ceruleus: regulation of neuronal activity and opiate withdrawal behaviors. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:4624–4629. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4701-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hjelmstad GO, Fields HL. Kappa opioid receptor inhibition of glutamatergic transmission in the nucleus accumbens shell. J. Neurophysiol. 2001;85:1153–1158. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.3.1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houshyar H, Gomez F, Manalo S, Bhargava A, Dallman MF. Intermittent morphine administration induces dependence and is a chronic stressor in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:1960–1972. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman SM, Fox H, Hong KI, Doebrick C, Sinha R. Stress and drug-cue-induced craving in opioid-dependent individuals in naltrexone treatment. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2007;15:134–143. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.2.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilgen M, Jain A, Kim HM, Trafton JA. The effect of stress on craving for methadone depends on the timing of last methadone dose. Behav. Res. Ther. 2008;46:1170–1175. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishimatsu M, Williams JT. Synchronous activity in locus coeruleus results from dendritic interactions in pericoerulear regions. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:5196–5204. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-16-05196.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jedema HP, Grace AA. Corticotropin-releasing hormone directly activates noradrenergic neurons of the locus ceruleus recorded in vitro. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:9703–9713. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2830-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khachaturian H, Watson SJ, Lewis ME, Coy D, Goldstein A, Akil H. Dynorphin immunocytochemistry in the rat central nervous system. Peptides. 1982;3:941–954. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(82)90063-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogan JH, Nestler EJ, Aghajanian GK. Elevated basal firing rates and enhanced responses to 8-Br-cAMP in locus coeruleus neurons in brain slices from opiate-dependent rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1992;211:47–53. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90261-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF. A role for brain stress systems in addiction. Neuron. 2008;59:11–34. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korf J, Bunney BS, Aghajanian GK. Noradrenergic neurons: morphine inhibition of spontaneous activity. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1974;25:165–169. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(74)90045-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosoyan HP, Grigoriadis DE, Tache Y. The CRF(1) receptor antagonist, NBI-35965, abolished the activation of locus coeruleus neurons induced by colorectal distension and intracisternal CRF in rats. Brain Res. 2005;1056:85–96. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreibich A, Reyes BAS, Curtis AL, Ecke L, Chavkin C, Van Bockstaele EJ, Valentino RJ. Presynaptic inhibition of diverse afferents to the locus ceruleus by kappa-opiate receptors: a novel mechanism for regulating the central norepinephrine system. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:6516–6525. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0390-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Land BB, Bruchas MR, Lemos JC, Xu M, Melief EJ, Chavkin C. The dysphoric component of stress is encoded by activation of the dynorphin kappa-opioid system. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:407–414. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4458-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechner SM, Curtis AL, Brons R, Valentino RJ. Locus coeruleus activation by colon distention: role of corticotropin-releasing factor and excitatory amino acids. Brain Res. 1997;756:114–124. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00116-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mague SD, Pliakas AM, Todtenkopf MS, Tomasiewicz HC, Zhang Y, Stevens WC, Jr., Jones RM, Portoghese PS, Carlezon WA., Jr Antidepressant-like effects of kappa-opioid receptor antagonists in the forced swim test in rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2003;305:323–330. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.046433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maj M, Turchan J, Smialowska M, Przewlocka B. Morphine and cocaine influence on CRF biosynthesis in the rat central nucleus of amygdala. Neuropeptides. 2003;37:105–110. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4179(03)00021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado R, Stinus L, Gold LH, Koob GF. Role of different brain structures in the expression of the physical morphine withdrawal syndrome. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1992;261:669–677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansour A, Fox CA, Burke S, Meng F, Thompson RC, Akil H, Watson SJ. Mu, delta, and kappa opioid receptor mRNA expression in the rat CNS: an in situ hybridization study. J. Comp. Neurol. 1994;350:412–438. doi: 10.1002/cne.903500307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markou A, Kosten TR, Koob GF. Neurobiological similarities in depression and drug dependence: a self-medication hypothesis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1998;18:135–174. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(97)00113-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin JP, Land BB, Li S, Pintar JE, Chavkin C. Prior activation of kappa opioid receptors by U50,488 mimics repeated forced swim stress to potentiate cocaine place preference conditioning. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:787–794. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin JP, Marton-Popovici M, Chavkin C. Kappa opioid receptor antagonism and prodynorphin gene disruption block stress-induced behavioral responses. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:5674–5683. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-13-05674.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally GP, Akil H. Role of corticotropin-releasing hormone in the amygdala and bed nucleus of the stria terminalis in the behavioral, pain modulatory, and endocrine consequences of opiate withdrawal. Neuroscience. 2002;112:605–617. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00105-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestler EJ. Cellular responses to chronic treatment with drugs of abuse. Crit. Rev. Neurobiol. 1993;7:23–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestler EJ, Alreja M, Aghajanian GK. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of opiate action: studies in the rat locus coeruleus. Brain Res. Bull. 1994;35:521–528. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(94)90166-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestler EJ, Alreja M, Aghajanian GK. Molecular control of locus coeruleus neurotransmission. Biol. Psychiatry. 1999;46:1131–1139. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00158-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestler EJ, Hope BT, Widnell KL. Drug addiction: a model for the molecular basis of neural plasticity. Neuron. 1993;11:995–1006. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90213-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestler EJ, Tallman JF. Chronic morphine treatment increases cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase activity in the rat locus coeruleus. Mol. Pharmacol. 1988;33:127–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogura M, Kita H. Dynorphin exerts both postsynaptic and presynaptic effects in the Globus pallidus of the rat. J. Neurophysiol. 2000;83:3366–3376. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.6.3366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens MJ, Nemeroff CB. Physiology and pharmacology of corticotropin-releasing factor. Pharmacol. Rev. 1991;43:425–473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page ME, Abercrombie ED. Discrete local application of corticotropin-releasing factor increases locus coeruleus discharge and extracellular norepinephrine in rat hippocampus. Synapse. 1999;33:304–313. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(19990915)33:4<304::AID-SYN7>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page ME, Akaoka H, Aston-Jones G, Valentino RJ. Bladder distention activates noradrenergic locus coeruleus neurons by an excitatory amino acid mechanism. Neuroscience. 1992;51:555–563. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90295-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page ME, Berridge CW, Foote SL, Valentino RJ. Corticotropin-releasing factor in the locus coeruleus mediates EEG activation associated with hypotensive stress. Neurosci. Lett. 1993;164:81–84. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90862-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paine TA, Tomasiewicz HC, Zhang K, Carlezon WA., Jr Sensitivity of the five-choice serial reaction time task to the effects of various psychotropic drugs in Sprague-Dawley rats. Biol. Psychiatry. 2007;62:687–693. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza PV, Le Moal M. Glucocorticoids as a biological substrate of reward: physiological and pathophysiological implications. Brain. Res. Brain. Res. Rev. 1997;25:359–372. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(97)00025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza PV, Le Moal M. The role of stress in drug self-administration. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1998;19:67–74. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(97)01115-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinnock RD. A highly selective kappa-opioid receptor agonist, CI-977, reduces excitatory synaptic potentials in the rat locus coeruleus in vitro. Neuroscience. 1992;47:87–94. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90123-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pliakas AM, Carlson RR, Neve RL, Konradi C, Nestler EJ, Carlezon WA., Jr Altered responsiveness to cocaine and increased immobility in the forced swim test associated with elevated cAMP response element-binding protein expression in nucleus accumbens. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:7397–7403. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-18-07397.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price RK, Risk NK, Haden AH, Lewis CE, Spitznagel EL. Post-traumatic stress disorder, drug dependence, and suicidality among male Vietnam veterans with a history of heavy drug use. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;76(Suppl):S31–43. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajkowski J, Kubiak P, Aston-Jones G. Locus coeruleus activity in monkey: phasic and tonic changes are associated with altered vigilance. Brain Res. Bull. 1994;35:607–616. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(94)90175-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen K, Aghajanian GK. Failure to block responses of locus coeruleus neurons to somatosensory stimuli by destruction of two major afferent nuclei. Synapse. 1989;4:162–164. doi: 10.1002/syn.890040210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen K, Krystal J. Opiate withdrawal and rat locus coeruleus:behavioral, electrophysiological and biochemical correlates. J. Neurosci. 1990;10:2308–2317. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-07-02308.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen K, Krystal JH, Aghajanian GK. Excitatory amino acids and morphine withdrawal: differential effects of central and peripheral kynurenic acid administration. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1991;105:508–512. doi: 10.1007/BF02244371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redmond E., Jr. The primary locus coeruleus and effects of clonidine on opiate withdawal. J. Clin. Psychol. 1982;43:25–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redmond DE, Jr., Huang YH. The primate locus coeruleus and effects of clonidine on opiate withdrawal. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 1982;43:25–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes BAS, Chavkin C, Van Bockstaele EJ. Subcellular targeting of kappa-opioid receptors in the rat nucleus locus coeruleus. J. Comp. Neurol. 2009;512:419–431. doi: 10.1002/cne.21880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes BAS, Drolet G, Van Bockstaele EJ. Dynorphin and stress-related peptides in rat locus coeruleus: contribution of amygdalar efferents. J. Comp. Neurol. 2008;508:663–675. doi: 10.1002/cne.21683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes BAS, Glaser JD, Magtoto R, Van Bockstaele EJ. Pro-opiomelanocortin colocalizes with corticotropin- releasing factor in axon terminals of the noradrenergic nucleus locus coeruleus. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2006;23:2067–2077. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes BAS, Glaser JD, Van Bockstaele EJ. Ultrastructural evidence for co-localization of corticotropin-releasing factor receptor and mu-opioid receptor in the rat nucleus locus coeruleus. Neurosci. Lett. 2007a;413:216–221. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.11.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes BAS, Johnson AD, Glaser JD, Commons KG, Van Bockstaele EJ. Dynorphin-containing axons directly innervate noradrenergic neurons in the rat nucleus locus coeruleus. Neuroscience. 2007b;145:1077–1086. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.12.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes BAS, Valentino RJ, Xu G, Van Bockstaele EJ. Hypothalamic projections to locus coeruleus neurons in rat brain. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2005;22:93–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivier C, Rivier J, Vale W. Inhibition of adrenocorticotropic hormone secretion in the rat by immunoneutralization of corticotropin-releasing factor. Science. 1982;218:377–379. doi: 10.1126/science.6289439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouzade-Dominguez ML, Curtis AL, Valentino RJ. Role of Barrington’s nucleus in the activation of rat locus coeruleus neurons by colonic distension. Brain Res. 2001;917:206–218. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02917-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakanaka M, Shibasaki T, Lederis K. Distribution and efferent projections of corticotropin-releasing factor-like immunoreactivity in the rat amygdaloid complex. Brain Res. 1986;382:213–238. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)91332-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selye H. The diseases of adaptation. Rec. Prog. Horm. Res. 1953;8:117. [Google Scholar]

- Selye H, Horava A. Stress Research. Science. 1953;117:509. doi: 10.1126/science.117.3045.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaham Y, Erb S, Leung S, Buczek Y, Stewart J. CP-154,526, a selective, non-peptide antagonist of the corticotropin-releasing factor1 receptor attenuates stress-induced relapse to drug seeking in cocaine- and heroin-trained rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1998;137:184–190. doi: 10.1007/s002130050608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaham Y, Funk D, Erb S, Brown TJ, Walker CD, Stewart J. Corticotropin-releasing factor, but not corticosterone, is involved in stress-induced relapse to heroin-seeking in rats. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:2605–2614. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-07-02605.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon HE, Eberle EL, Mitch CH, McKinzie DL, Statnick MA. Effects of kappa opioid receptor agonists on attention as assessed by a 5-choice serial reaction time task in rats. Neuropharmacology. 2007;53:930–941. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shippenberg TS, Herz A. Differential effects of mu and kappa opioid systems on motivational processes. NIDA Res Monogr. 1986;75:563–566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirayama Y, Ishida H, Iwata M, Hazama GI, Kawahara R, Duman RS. Stress increases dynorphin immunoreactivity in limbic brain regions and dynorphin antagonism produces antidepressant-like effects. J. Neurochem. 2004;90:1258–1268. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons ML, Chavkin C. Endogenous opioid regulation of hippocampal function. Int., Rev. Neurobiol. 1996;39:145–196. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7742(08)60666-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R. How does stress increase risk of drug abuse and relapse? Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;158:343–359. doi: 10.1007/s002130100917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R, Catapano D, O’Malley S. Stress-induced craving and stress response in cocaine dependent individuals. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;142:343–351. doi: 10.1007/s002130050898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R, Garcia M, Paliwal P, Kreek MJ, Rounsaville BJ. Stress-induced cocaine craving and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal responses are predictive of cocaine relapse outcomes. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2006;63:324–331. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.3.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R, Kimmerling A, Doebrick C, Kosten TR. Effects of lofexidine on stress-induced and cue-induced opioid craving and opioid abstinence rates: preliminary findings. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;190:569–574. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0640-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stohr T, Almeida OF, Landgraf R, Shippenberg TS, Holsboer F, Spanagel R. Stress- and corticosteroid-induced modulation of the locomotor response to morphine in rats. Behav Brain Res. 1999;103:85–93. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(99)00027-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton LC, Grahn RE, Wiertelak EP, Watkins LR, Maier SF. Inescapable shock-induced potentiation of morphine analgesia in rats: involvement of opioid, GABAergic, and serotonergic mechanisms in the dorsal raphe nucleus. Behav. Neurosci. 1997;111:816–824. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.111.4.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svingos AL, Chavkin C, Colago EE, Pickel VM. Major coexpression of kappa-opioid receptors and the dopamine transporter in nucleus accumbens axonal profiles. Synapse. 2001;42:185–192. doi: 10.1002/syn.10005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svingos AL, Colago EE. Kappa-Opioid and NMDA glutamate receptors are differentially targeted within rat medial prefrontal cortex. Brain Res. 2002;946:262–271. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02894-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svingos AL, Colago EE, Pickel VM. Cellular sites for dynorphin activation of kappa-opioid receptors in the rat nucleus accumbens shell. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:1804–1813. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-05-01804.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terman GW, Lewis JW, Liebeskind JC. Two opioid forms of stress analgesia: studies of tolerance and cross-tolerance. Brain Res. 1986;368:101–106. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)91046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terman GW, Liebeskind JC. Relation of stress-induced analgesia to stimulation-produced analgesia. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1986;467:300–308. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1986.tb14636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjoumakaris SI, Rudoy C, Peoples J, Valentino RJ, Van Bockstaele EJ. Cellular interactions between axon terminals containing endogenous opioid peptides or corticotropin-releasing factor in the rat locus coeruleus and surrounding dorsal pontine tegmentum. J. Comp. Neurol. 2003;466:445–456. doi: 10.1002/cne.10893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomchek SD, Dunn W. Sensory processing in children with and without autism: a comparative study using the short sensory profile. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2007;61:190–200. doi: 10.5014/ajot.61.2.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usher M, Cohen JD, Servan-Schreiber D, Rajkowski J, Aston-Jones G. The role of locus coeruleus in the regulation of cognitive performance. Science. 1999;283:549–554. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5401.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vale W, Spiess J, Rivier C, Rivier J. Characterization of a 41-residue ovine hypothalamic peptide that stimulates secretion of corticotropin and beta-endorphin. Science. 1981;213:1394–1397. doi: 10.1126/science.6267699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentino RJ, Foote SL. Corticotropin-releasing factor disrupts sensory responses of brain noradrenergic neurons. Neuroendocrinology. 1987;45:28–36. doi: 10.1159/000124700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentino RJ, Foote SL. Corticotropin-releasing hormone increases tonic but not sensory-evoked activity of noradrenergic locus coeruleus neurons in unanesthetized rats. J. Neurosci. 1988;8:1016–1025. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-03-01016.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentino RJ, Foote SL, Page ME. The locus coeruleus as a site for integrating corticotropin-releasing factor and noradrenergic mediation of stress responses. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1993;697:173–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb49931.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentino RJ, Page M, Van Bockstaele EJ, Aston-Jones G. Corticotropin-releasing factor innervation of the locus coeruleus region: distribution of fibers and sources of input. Neuroscience. 1992;48:689–705. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90412-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentino RJ, Page ME, Curtis AL. Activation of noradrenergic locus coeruleus neurons by hemodynamic stress is due to local release of corticotropin-releasing factor. Brain Res. 1991;555:25–34. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90855-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentino RJ, Rudoy C, Saunders A, Liu XB, Van Bockstaele EJ. Corticotropin-releasing factor is preferentially colocalized with excitatory rather than inhibitory amino acids in axon terminals in the peri-locus coeruleus region. Neuroscience. 2001;106:375–384. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00279-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentino RJ, Van Bockstaele EJ. Functional interactions between stress neuromediators and the locus coeruleus-noradrenaline system. In: Steckler T, Kalin NH, Reul JMHM, editors. Handbook of Stress and the Brain. Elsevier; 2005. pp. 465–486. [Google Scholar]

- Valentino RJ, Wehby RG. Corticotropin-releasing factor: evidence for a neurotransmitter role in the locus ceruleus during hemodynamic stress. Neuroendocrinology. 1988a;48:674–677. doi: 10.1159/000125081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentino RJ, Wehby RG. Morphine effects on locus ceruleus neurons are dependent on the state of arousal and availability of external stimuli: studies in anesthetized and unanesthetized rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1988b;244:1178–1186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentino RJ, Wehby RG. Locus ceruleus discharge characteristics of morphine-dependent rats: effects of naltrexone. Brain Res. 1989;488:126–134. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)90701-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bockstaele EJ, Branchereau P, Pickel VM. Morphologically heterogeneous met-enkephalin terminals form synapses with tyrosine hydroxylase-containing dendrites in the rat nucleus locus coeruleus. J. Comp. Neurol. 1995;363:423–438. doi: 10.1002/cne.903630307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bockstaele EJ, Carvalho AF, Reyes BAS, editors. Amygdalar efferents that co-express dynorphin and corticotropin-releasing factor target noradrenergic neurons of the rat locus coeruleus. Society for Neuroscience; Chicago, Il: 2009. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Van Bockstaele EJ, Chan J. Electron microscopic evidence for coexistence of leucine5-enkephalin and gamma-aminobutyric acid in a subpopulation of axon terminals in the rat locus coeruleus region. Brain Res. 1997;746:171–182. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)01194-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bockstaele EJ, Chan J, Pickel VM. Input from central nucleus of the amygdala efferents to pericoerulear dendrites, some of which contain tyrosine hydroxylase immunoreactivity. J. Neurosci. Res. 1996a;45:289–302. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19960801)45:3<289::AID-JNR11>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bockstaele EJ, Colago EE, Aicher S. Light and electron microscopic evidence for topographic and monosynaptic projections from neurons in the ventral medulla to noradrenergic dendrites in the rat locus coeruleus. Brain Res. 1998a;784:123–138. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)01250-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bockstaele EJ, Colago EE, Cheng P, Moriwaki A, Uhl GR, Pickel VM. Ultrastructural evidence for prominent distribution of the mu-opioid receptor at extrasynaptic sites on noradrenergic dendrites in the rat nucleus locus coeruleus. J. Neurosci. 1996b;16:5037–5048. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-16-05037.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bockstaele EJ, Colago EE, Moriwaki A, Uhl GR. Mu-opioid receptor is located on the plasma membrane of dendrites that receive asymmetric synapses from axon terminals containing leucine-enkephalin in the rat nucleus locus coeruleus. J. Comp. Neurol. 1996c;376:65–74. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19961202)376:1<65::AID-CNE4>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bockstaele EJ, Colago EE, Pickel VM. Enkephalin terminals form inhibitory-type synapses on neurons in the rat nucleus locus coeruleus that project to the medial prefrontal cortex. Neuroscience. 1996d;71:429–442. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00432-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]