Abstract

Context:

Acquired central hypothyroidism is rare, especially when isolated, and is typically associated with detectable, although biologically inactive, serum TSH.

Objective:

We describe a 56-yr-old woman with profound central hypothyroidism and partial central hypoadrenalism, in the absence of other endocrine abnormalities. In contrast to most cases of central hypothyroidism, serum TSH remained undetectable for 9 months before the initiation of thyroid hormone and hydrocortisone treatment. A test for pituitary autoantibody was moderately positive. Serum free T4, serum T3, and neck radioiodine uptake were low but detectable. The thyroid and pituitary glands appeared morphologically normal on neck ultrasound and head magnetic resonance imaging, respectively.

Settings:

The study was conducted in a tertiary academic medical center.

Conclusions:

This case illustrates the variable clinical presentation of pituitary autoimmunity. The persistence of low but detectable thyroid hormone levels and radioiodine neck uptake in the absence of TSH suggests that significant TSH-independent thyroid hormone synthesis may occur in the normal thyroid.

Central hypothyroidism (CH) is an uncommon form of hypothyroidism. It originates from insufficient TSH stimulation of an otherwise normal thyroid gland and is diagnosed by the demonstration of decreased free T4 (FT4) levels in the presence of low or inappropriately normal TSH levels. Although the pathogenesis of CH is centered on a defective TSH, TSH is in fact detectable and often within normal limits (1). This paradox is explained by a reduced biological activity of the measured (immunoreactive) TSH in many cases of CH (2).

CH can be classified, similar to other central hormone deficiencies, into congenital or acquired and can occur in isolation or combined to other forms of hypopituitarism. Congenital CH most commonly results from mutations in genes involved in pituitary organogenesis (like LHX3, LHX4, and PROP1) or in the differentiation of a particular endocrine cell lineage (like PIT1, which dictates the development of GH-, prolactin-, and TSH-producing cells). More rarely, CH results from isolated defects in the TSH β-subunit gene (3). Congenital CH affects about one in 30,000 newborns and can only be detected in newborn screening programs that measure simultaneously T4 (or FT4) and TSH, or T4, T4 binding globulin, and TSH (4).

Acquired CH manifests later in life, usually combined with other anterior pituitary hormone deficiencies. The etiology of these late-onset combined pituitary hormone deficiencies remains unclear. It has been traditionally linked with autoimmune hypophysitis (AH), and quite interestingly, a recent article has shown in three patients the presence of antibodies recognizing the pituitary-specific transcription factor PIT1 (5).

The degree of hypothyroidism in patients with CH is usually mild and not associated with undetectable thyroid hormone levels. It is unclear whether this low severity is due to a residual TSH activity or to a TSH-independent constitutive secretion of thyroid hormones from the thyroid gland. We describe a case of severe CH and moderate central adrenal insufficiency (CAI) in the presence of a radiologically normal pituitary gland and pituitary antibodies. We also provide for the first time in vivo evidence of spontaneous thyroid hormone production by an apparently normal thyroid, in the absence of circulating immunoreactive TSH.

Case Presentation

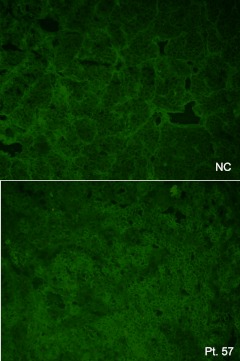

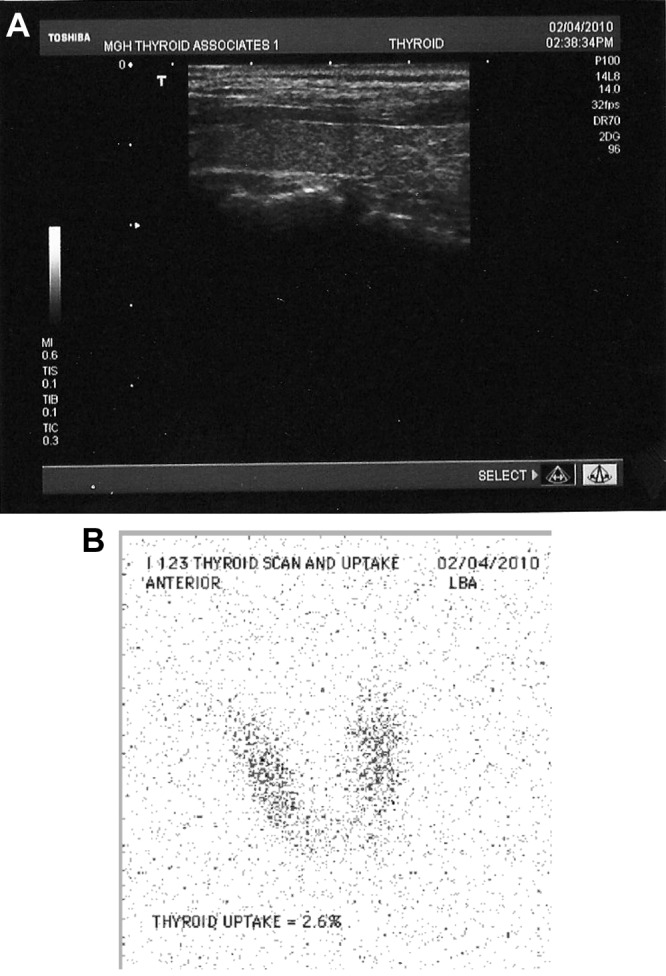

In November 2009, a 56-yr-old woman presented the Thyroid Unit of the Massachusetts General Hospital for evaluation of a suppressed TSH. In June 2009, during her yearly physical exam at another hospital, she had been found to have atrial fibrillation. The patient was prescribed metoprolol, digoxin, and warfarin. No additional medications were prescribed or taken at any time during our observation. Thyroid function tests in early July 2009 showed undetectable TSH. At the end of July, repeat thyroid function tests confirmed undetectable TSH, FT4 was 0.64 ng/dl (normal range, 0.71–1.85), and total T3 was 124 ng/dl (normal range, 80–200). Tests for antithyroid peroxidase antibodies were negative, whereas the antithyroglobulin antibody was weakly positive at 32 IU/ml (normal range, 0–20). On August 6, 2009, thyroid uptake 3 and 24 h after the administration of 300 μCi I-123 was 2.7 and 2.9%, respectively. The patient was diagnosed with painless thyroiditis and advised to monitor her thyroid function tests in the following weeks. She was advised that cardioversion of her atrial fibrillation could be attempted after full euthyroidism had returned. In the following months, the patient moved to the Boston area and established her care at the Massachusetts General Hospital. Her past medical history was significant for several years of amenorrhea in her twenties, attributed to strenuous exercise and low body weight. There was no history of anorexia nervosa. During that period, she had undergone several treatments in another country, including “steroids.” She had no documentation on these treatments. She eventually recovered her periods and had several pregnancies, all ending with first-trimester miscarriages. She carried one pregnancy to term after in vitro fertilization at age 41, after which she had oligomenorrhea until her last menstrual period at age 49. She denies current or past use of oral, topical, or inhaled glucocorticoids, thyroid hormone, and iodinated supplements. There was no history of head trauma and/or head exposure to therapeutic ionizing radiation. On exam, she was a well-appearing woman. Her body mass index was 20.9 kg/m2. There was no skin hyperpigmentation. The eyebrows were sparse. The thyroid was nonpalpable. Her cardiac exam revealed an irregular rhythm with a rate of 69 bpm and blood pressure of 96/65 mm Hg. The exam of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis was normal. Her thyroid function tests were repeated and then monitored over the next few months and demonstrated CH with undetectable TSH (Table 1). A neck ultrasound showed a small, homogenous, and normoechogenic thyroid gland (Fig. 1A), whereas a repeat thyroid I-123 uptake in February 2010 (6 months after the first scan) showed 2.9% uptake at 24 h. The thyroid silhouette was barely appreciable on the scintigraphic images but was normal in size (Fig. 1B). Tests for the serum FSH, LH, IGF-I, prolactin, ferritin, plasma renin activity and aldosterone, and urinary iodine were within the normal range and appropriate for the patient's menopausal status (Table 2). The baseline cortisol was low and responded poorly to the im injection of synthetic ACTH (250 μg), consistent with adrenal insufficiency. A baseline ACTH was not measured due to lab error, but normal renin and aldosterone suggest a central etiology for the adrenal insufficiency (6). The pituitary and hypothalamus appeared normal on gadolinium-enhanced head magnetic resonance imaging. Antipituitary antibody was tested by immunofluorescence on human cadaveric pituitary sections (7) and found to be moderately positive (Fig. 2). To rule out interference in the TSH assay, we performed recovery experiments as follows. We added to the patient's serum an equal volume of the TSH calibrator solution from the kit (Roche, Indianapolis, IN), which has a target concentration of 1.8 μU/ml. We then measured TSH on the mixture after a brief incubation at room temperature. An assay control was also incubated and tested. The patient/calibrator mixture and the assay control gave TSH concentrations of 1.77 and 1.78 U/ml, respectively, after correcting for the dilution. The test was repeated after overnight incubation at 37 C. In this second experiment, the patient/calibrator mixture gave a TSH concentration of 1.46 μU/ml, and the control measured 1.23 μU/ml. In addition, serum TSH antibodies were negative by a commercially available RIA (Quest Diagnostics, Madison, NJ). These data suggest that serum interference is very unlikely to explain the undetectable TSH. Protein-bound T4 electrophoresis (Quest Diagnostics) on the patient's serum showed no abnormal binding, ruling out falsely low T4 levels due to thyroid hormone antibody or other factors. The patient was diagnosed with CH and incomplete CAI and was treated with replacement doses of hydrocortisone and thyroid hormones (desiccated thyroid extract was used instead of synthetic T4 at the patient's request). Her thyroid FT4 and T3 levels normalized as expected upon treatment, confirming the absence of serum interference in the thyroid hormone assays, whereas her TSH remains undetectable.

Table 1.

Thyroid tests during the period of observation

| Date | FT4 (0.9–1.8 ng/ml) | T3 (60–181 ng/dl) | TSH (0.4–5.0 μU/ml) | RAIU at 24 h | TPO Ab | Tg Ab |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| July–August 2009 | 0.64a | <0.01 | 2.9% | Neg | 32 | |

| 10/01/2009 | 0.8 | nd | <0.01 | |||

| 11/13/2009 | 1.1 | 82 | <0.01 | |||

| 1/5/2010 | 0.6 | 46 | <0.01 | 2.9% | ||

| 4/5/2010 | 0.8 | 56 | <0.01 |

RAIU, Radioactive iodine uptake; TPO Ab, thyroid peroxidase antibodies; Tg Ab, thyroglobulin antibodies; nd, not determined.

The reference range here is 0.71–1.85.

Fig. 1.

A, Ultrasonographic image of the right thyroid lobe demonstrating a small, but otherwise normal thyroid gland. B, Thyroid scan after the administration of 200 μCi I-123.

Table 2.

Selected additional blood and urine tests

| Test | Value | Range |

|---|---|---|

| FSH (U/liter) | 44.4 | 18–153 |

| LH (U/liter) | 52.6 | 16–64 |

| Thyroid-stimulating Ig | Negative | Negative |

| Protein-bound T4 electrophoresis | No abnormal binding | |

| Free T3 (pg/dl) | 140 | 230–420 |

| rT3 (ng) | 5 | 11–32 |

| Prolactin (ng/ml) | 7.9 | 0–15 |

| IGF-I (ng/ml) | 146 | 90–360 |

| Cortisol (μg/dl) | ||

| Baseline | 4.1 | |

| 30 min after ACTH | 1.7 | |

| 60 min after ACTH | 14.5 | >19 |

| Urinary iodine (μg/liter) | 53 | 34–523 |

| PRA (ng/ml · h) | <0.6 | <0.6–3.0 |

| Aldosterone (ng/dl) | 14 | <21 |

| Ferritin (ng/ml) | 102 | 10–291 |

PRA, Plasma renin activity.

Fig. 2.

Indirect immunofluorescence on cadaveric human pituitary slices. The upper panel shows a healthy control (NC), whereas the lower panel shows the patient's serum. A diffuse cytoplasmic fluorescence of moderate intensity is seen focally in large numbers of anterior pituitary cells.

Discussion

Isolated acquired CH is a rare condition diagnosed biochemically based on the finding of low T4 and inappropriately normal or low TSH (8). Its diagnosis requires the exclusion of artifacts in the measurement of TSH, thyroid hormones, or both. Extensive tests for abnormal thyroid hormone or TSH serum binding, detailed in the previous section, ruled out this possibility in our patient.

In addition, the low thyroidal uptake repeatedly demonstrated in our patient provides strong biological evidence of the absence of thyroidal stimulation.

Other alternative explanations for this presentation include the recovery phase of any form of thyrotoxicosis, when ensuing hypothyroidism is manifested by low thyroid hormone levels, but TSH secretion has not yet recovered in full. TSH suppression in these situations, however, is usually transient, especially if frank hypothyroidism is present, whereas observation of thyroid function tests in our patient for a period of over 6 months showed no signs of recovery of TSH secretion. In addition, the normal thyroid texture on ultrasound and the absence of thyroid peroxidase antibodies make the diagnosis of autoimmune thyroiditis unlikely, even in the presence of minimally elevated thyroglobulin antibody. Finally, in T3 factitious thyrotoxicosis, chronically undetectable T4 and TSH are observed in adjunct to a rapid drop in T3 levels when the intake of the hormone is suddenly stopped (9). The condition can therefore transiently mimic CH. Our patient has repeatedly denied the intake of thyroid hormone and never has shown signs of thyrotoxicosis during several examinations. In addition, T4 levels were low but not undetectable and paralleled the T3 levels at all times. Although the presence of a nonimmunoreactive but weakly bioactive TSH molecule could in theory explain our findings, this hypothesis cannot be tested because all tests for TSH bioactivity require preliminary immunoadsorption of TSH and, therefore, can only be performed on an immunoreactive TSH. Moreover, such an occurrence has never been observed to our knowledge. We therefore surmise that this is an unusual case of acquired CH where TSH remained undetectable at all times in the absence of other pituitary abnormalities, except for mild CAI.

CAI and CH are found uncommonly in the setting of nonselective hypothalamic-pituitary injury, such as pituitary macroadenomas, brain radiation therapy, or after traumatic brain injury (10–13). The incidence of CAI and CH appears to be low also in most infiltrative or inflammatory disorders of the pituitary, such as neurosarcoidosis and hystiocytosis X (14). It appears thus that the corticotroph and thyrotroph cell populations are particularly resistant to hypothalamic-pituitary injury and are often spared, even when other axes are involved. As an exception to this rule, both CAI and CH are common features of autoimmune (or lymphocytic) hypophysitis (AH) (4). A comprehensive review of all the case reports and series published in the English literature shows approximately 600 cases of biopsy-proven or clinically suspected AH. In this series, CAI, CH, and hypogonadal hypogonadism were the predominant endocrine features (Table 3). Headaches and symptoms of optic chiasm compression are also very common presenting symptoms in AH, uncharacteristically absent in our patient, in agreement with normal magnetic resonance imaging findings. The finding of CH and CAI in association with pituitary autoantibodies strongly suggests AH as the cause of this patient's endocrine abnormalities. Although a pituitary biopsy is currently required to establish a diagnosis of certainty of AH, this procedure is only indicated in the presence of a symptomatic pituitary mass and when other etiologies are in the differential. This patient's history seems to indicate a smoldering form of AH. Indeed, variable courses can be observed in many autoimmune conditions. As a well-recognized example, Hashimoto's thyroiditis can present in its goitrous form, with rapid progression through a short phase of thyrotoxicosis followed by rapid conversion into hypothyroidism, or more subtly in its atrophic form, eventually leading to classic myxedema (15, 16).

Table 3.

Prevalence of distinct pituitary axis hypofunction in 579 total cases of autoimmune hypophysitis from the indexed English language medical literature

| Biopsy proven | Clinical diagnosis | All | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adrenal insufficiency | 172/387 (55.8%) | 111/180 (61%) | 283/488 (58%) |

| CH | 163/314 (51.9%) | 79/177 (44.6%) | 242/491 (49.3%) |

| Hypogonadal hypogonadism | 154/280 (55.0%) | 74/162 (45.6%) | 228/442 (51.6%) |

| GH deficiency | 76/228 (33.3%) | 53/144 (36.8%) | 129/372 (34.7%) |

| Low prolactin | 53/293 (18.1%) | 41/165 (24.8%) | 94/458 (20.5%) |

| Diabetes insipidus | 122/192 (63.5%) | 74/110 (67.0%) | 196/132 (64.9%) |

Denominators in each cell indicate the number of cases tested for each type of the dysfunction. Numerators indicate the number of cases found to be defective.

Finally, of great interest was the demonstration that, despite undetectable TSH levels, FT4 and T3 were low but detectable at all times in our patient. These findings indicate some degree of thyroid activity and are supported by the low, but not nil, radioactive iodine trapping in the thyroid. Although thyroid autonomy is a possible explanation, the absence of thyroid nodules on ultrasound and the homogenous distribution of the minimal observed uptake are against this hypothesis. The absence of thyroid-stimulating Ig also rules out the unlikely co-occurrence of CH and mild Graves' disease. We favor the existence of some degree of constitutional thyroid hormone synthesis in the unstimulated thyroid. This interpretation is somewhat at odds with the model of congenital CH due to homozygous mutations in the β-subunit of the TSH receptor gene (17). In this condition, neonates are born with almost absent TSH activity, a situation physiologically similar to our patient's. In contrast with our case, however, these children present with almost undetectable thyroid hormone levels (18). The shorter half-life of thyroid hormone in children is one potential explanation for this discrepancy (19). Indeed, in at least one of the cases studied by Dacou-Voutetakis et al. (20), the neck radioiodine uptake was as high as 8%, also suggesting some TSH-independent thyroid activity, despite undetectable thyroid hormone levels. It is also conceivable that the fetal thyroid requires more than a constitutive degree of TSH receptor activation to develop the complex enzymatic machine necessary for a detectable 24-h radioiodine uptake. Our observation seems to confirm for the first time in vivo the previous in vitro studies indicating a constitutional cAMP production by the human TSH receptor, in the absence of the ligand (21). One is tempted to speculate that this physiological mechanism responds to the necessity of preventing extreme hypothyroidism. Indeed, our patient did not have any of the classic symptoms of myxedema, such as those observed in complete autoimmune thyroid gland destruction.

Acknowledgments

G.B. and P.C. acknowledge with gratitude Prof. Stefano Mariotti, currently in Cagliari, Italy. His mentorship early during our career planted the seed for our ongoing interest in thyroid pathophysiology.

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grant DK 08035 (to P.C.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to declare.

Footnotes

- AH

- Autoimmune hypophysitis

- CAI

- central adrenal insufficiency

- CH

- central hypothyroidism

- FT4

- free T4.

References

- 1. Patel YC, Burger HG. 1973. Serum thyrotropin (TSH) in pituitary and/or hypothalamic hypothyroidism: normal or elevated basal levels and paradoxical responses to thyrotropin-releasing hormone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 37:190–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Persani L, Ferretti E, Borgato S, Faglia G, Beck-Peccoz P. 2000. Circulating thyrotropin bioactivity in sporadic central hypothyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 85:3631–3635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. van Tijn DA, de Vijlder JJ, Verbeeten B, Jr, Verkerk PH, Vulsma T. 2005. Neonatal detection of congenital hypothyroidism of central origin. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90:3350–3359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yamada M, Mori M. 2008. Mechanisms related to the pathophysiology and management of central hypothyroidism. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab 4:683–694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yamamoto M, Iguchi G, Takeno R, Okimura Y, Sano T, Takahashi M, Nishizawa H, Handayaningshi AE, Fukuoka H, Tobita M, Saitoh T, Tojo K, Mokubo A, Morinobu A, Iida K, Kaji H, Seino S, Chihara K, Takahashi Y. 2011. Adult combined GH, prolactin, and TSH deficiency associated with circulating PIT-1 antibody in humans. J Clin Invest 121:113–119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Oelkers W, Diederich S, Bähr V. 1992. Diagnosis and therapy surveillance in Addison's disease: rapid adrenocorticotropin (ACTH) test and measurement of plasma ACTH, renin activity, and aldosterone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 75:259–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bottazzo GF, Pouplard A, Florin-Christensen A, Doniach D. 1975. Autoantibodies to prolactin-secreting cells of human pituitary. Lancet 2:97–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lania A, Persani L, Beck-Peccoz P. 2008. Central hypothyroidism. Pituitary 11:181–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sylvia Vela B, Dorin RI. 1991. Factitious triiodothyronine toxicosis. Am J Med 90:132–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Agha A, Sherlock M, Brennan S, O'Connor SA, O'Sullivan E, Rogers B, Faul C, Rawluk D, Tormey W, Thompson CJ. 2005. Hypothalamic-pituitary dysfunction after irradiation of nonpituitary brain tumors in adults. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90:6355–6360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Littley MD, Shalet SM, Beardwell CG, Ahmed SR, Applegate G, Sutton ML. 1989. Hypopituitarism following external radiotherapy for pituitary tumours in adults. Q J Med 70:145–160 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Greenman Y, Stern N. 2009. Non-functioning pituitary adenomas. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 23:625–638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Agha A, Rogers B, Sherlock M, O'Kelly P, Tormey W, Phillips J, Thompson CJ. 2004. Anterior pituitary dysfunction in survivors of traumatic brain injury. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89:4929–4936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Carpinteri R, Patelli I, Casanueva FF, Giustina A. 2009. Pituitary tumours: inflammatory and granulomatous expansive lesions of the pituitary. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 23:639–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bastenie PA, Bonnyns M, Neve P, Vanhaelst L, Chailly M. 1967. Clinical and pathological significance of asymptomatic atrophic thyroiditis. A condition of latent hypothyroidism. Lancet 1:915–918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gluck FB, Nusynowitz ML, Plymate S. 1975. Chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis, thyrotoxicosis, and low radioactive iodine uptake. Report of four cases. N Engl J Med 293:624–628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Miyai K, Azukizawa M, Kumahara Y. 1971. Familial isolated thyrotropin deficiency with cretinism. N Engl J Med 285:1043–1048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Borck G, Topaloglu AK, Korsch E, Martiné U, Wildhardt G, Onenli-Mungan N, Yuksel B, Aumann U, Koch G, Ozer G, Pfäffle R, Scherberg NH, Refetoff S, Pohlenz J. 2004. Four new cases of congenital secondary hypothyroidism due to a splice site mutation in the thyrotropin-β gene: phenotypic variability and founder effect. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89:4136–4141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Haddad HM. 1960. Rates of I 131-labeled thyroxine metabolism in euthyroid children. J Clin Invest 39:1590–1594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dacou-Voutetakis C, Feltquate DM, Drakopoulou M, Kourides IA, Dracopoli NC. 1990. Familial hypothyroidism caused by a nonsense mutation in the thyroid-stimulating hormone β-subunit gene. Am J Hum Genet 46:988–993 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Van Sande J, Swillens S, Gerard C, Allgeier A, Massart C, Vassart G, Dumont JE. 1995. In Chinese hamster ovary K1 cells dog and human thyrotropin receptors activate both the cyclic AMP and the phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate cascades in the presence of thyrotropin and the cyclic AMP cascade in its absence. Eur J Biochem 229:338–343 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]