Abstract

The objective of the present study was to investigate vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA) isoform regulation of cell fate decisions of spermatogonial stem cells (SSC) in vivo. The expression pattern and cell-specific distribution of VEGF isoforms, receptors, and coreceptors during testis development postnatal d 1–180 suggest a nonvascular function for VEGF regulation of early germ cell homeostasis. Populations of undifferentiated spermatogonia present shortly after birth were positive for VEGF receptor activation as demonstrated by immunohistochemical analysis. Thus, we hypothesized that proangiogenic isoforms of VEGF (VEGFA164) stimulate SSC self-renewal, whereas antiangiogenic isoforms of VEGF (VEGFA165b) induce differentiation of SSC. To test this hypothesis, we used transplantation to assay the stem cell activity of SSC obtained from neonatal mice treated daily from postnatal d 3–5 with 1) vehicle, 2) VEGFA164, 3) VEGFA165b, 4) IgG control, 5) anti-VEGFA164, and 6) anti-VEGFA165b. SSC transplantation analysis demonstrated that VEGFA164 supports self-renewal, whereas VEGFA165b stimulates differentiation of mouse SSC in vivo. Gene expression analysis of SSC-associated factors and morphometric analysis of germ cell populations confirmed the effects of treatment on modulating the biological activity of SSC. These findings indicate a nonvascular role for VEGF in testis development and suggest that a delicate balance between VEGFA164 and VEGFA165b isoforms orchestrates the cell fate decisions of SSC. Future in vivo and in vitro experimentation will focus on elucidating the mechanisms by which VEGFA isoforms regulate SSC homeostasis.

Spermatogonial stem cells (SSC) reside in the seminiferous tubules of the testis and are the only adult stem cell population capable of transmitting genes to offspring. SSC and their ability to self-renew ensure maintenance of fertility throughout the lifespan of the male, whereas SSC differentiation functions to provide germ cell progeny leading to the production of spermatozoa. The process, spermatogenesis, is one of the most productive biological processes in mammals, leading to a virtually unlimited supply of spermatozoa throughout the lifespan of an adult male. Thus, the balance between SSC self-renewal and differentiation, or homeostasis, is critical for male fertility.

In rodents, gonocytes are the first male-specific germ cells present in the testis during fetal and postnatal development (1), and these cells undergo mitotic arrest late in gestation until shortly after birth when they resume mitosis around postnatal d 1.5 (P1.5) to P3 (2). Gonocytes ultimately give rise to the SSC pool but must first migrate from the center of the testicular cords to the basement membrane, an event initiated around P3 (3). During this period of migration, gonocytes resume mitosis (4, 5) and undergo one of three fates: some mature into SSC, some differentiate and initiate spermatogenesis, whereas the remainder degenerate (4–6). In vivo transplantation studies indicate that testicular germ cells obtained from P0–P3 mice can colonize recipient testes but do not initiate self-renewal or establish donor-derived spermatogenesis (1, 6). In contrast, germ cells collected from P4–P5 testes generate large areas of donor-derived spermatogenesis in recipients after colonization (7), indicating the presence of robust stem cell activity and SSC formation.

SSC reside near the basement membrane of seminiferous tubules and are intimately associated with somatic cells that include Sertoli cells, peritubular myoid cells, and Leydig cells. Accordingly, the environmental cues influencing the cell fate decisions of SSC during this critical period of germ cell development remain unclear, but it is thought that intrinsic and extrinsic factors produced by the stem cell niche may function to modulate SSC homeostasis in vivo (8). For example, glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) produced by Sertoli cells functions to directly regulate the maintenance and self-renewal of SSC (9), a result confirmed by transplantation (10). However, identification of the additional factors regulating SSC remains difficult because no bona fide SSC markers exist, and the only way stem cell activity can be determined is with use of the transplantation assay (11).

Several reports suggest that blood vessels in the interstitial compartment of the testis constitute a niche microenvironment for undifferentiated spermatogonia and SSC populations in the postnatal testis (12–14). Along those lines, angiogenic factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA) and its receptors have been implicated in nonvascular roles such as directing testis morphogenesis in mice (15, 16) and regulating the biological activity of undifferentiated germ cells in bovine testis tissue (17) in a manner independent of angiogenesis (17, 18). These studies have yet to 1) determine the function of VEGF family molecules on regulating the cell fate decisions of SSC and 2) differentiate between the effects of proangiogenic isoforms (VEGFxxx) and antiangiogenic (VEGFxxxb) isoforms. Alternative splicing of VEGFA yields multiple proangiogenic isoforms (VEGFA111, VEGFA121, VEGFA145, VEGFA162, VEGFA165, VEGFA183, and VEGFA206) and multiple antiangiogenic (VEGFA121b, VEGFA145b, VEGFA165b, VEGFA 183b, and VEGFA189b) isoforms (19). VEGFA165 (VEGFA164 in mice) and VEGFA165b are the most prevalent and biologically active splice variants in humans, respectively. The VEGFA splice variants are generated by proximal and distal splice sites in exon 8 of the VEGFA gene (19). Moreover, these families of VEGFA isoforms have diverse functions in vivo: VEGFA165 stimulates endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and survival (20–22), whereas VEGFA165b isoforms inhibit VEGFA165-induced signal transduction and physiological outcomes (23–29). Three VEGFA receptors (VEGFR) have been identified called FLT1 (VEGFR1), KDR (VEGFR2), and VEGFR3 with kinase insert domain receptor (KDR) eliciting the greatest intracellular signaling for promoting cell proliferation, whereas fms-related tyrosine kinase 1 (FLT1) activation stimulates cell migration; the role of VEGFR3 is presently unknown. In addition to multiple receptors, VEGFA isoforms interact with two soluble cofactors, neuropilin 1 (NRP1) and NRP2, that can either facilitate or suppress VEGFA isoform-receptor interaction and subsequent signaling. Nevertheless, signal transduction events triggered by VEGFA family members within nonvascular targets are poorly understood, especially in the postnatal testis.

The objective of the present study was to evaluate the role of VEGFA isoform signaling in vivo in regard to regulating the cell fate decisions of SSC. We hypothesized that proangiogenic isoforms of VEGFA (VEGFA164) stimulate SSC self-renewal, whereas antiangiogenic isoforms (VEGFA165b) induce differentiation of SSC. To test this hypothesis, we used the functional SSC transplantation technique to assay the effects of VEGFA isoform treatment combinations on the stem cell activity of SSC in vivo.

Materials and Methods

Animal care and treatments

All animal experiments were approved by Washington State University Animal Care and Use committees and were conducted in accordance with the Guiding Principles for the Care and Use of Research Animals of the National Institutes of Health. Animals were housed in a standard animal facility and provided ad libitum access to food and water. Rosa26 (stock no. 002192) and C57BL/6 (stock no. 000664) mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME).

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis

qRT-PCR was conducted as previously described (17) using an iCycler iQ (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) detection system. Total RNA was prepared from C57BL/6 testis tissue using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. RNA concentration and purity were determined using a Nanodrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Schwerte, Germany), and only samples with a 260/280 ratio of at least 1.8 were used for qRT-PCR analysis. A list and description of TaqMan probe sets used for gene expression in the current study are provided (Table 1). Ribosomal protein S2 was used as a normalization reference. Relative quantification of mRNA levels was calculated using the Q-Gene method (30). At least three donors were used for each age and treatment (n ≥ 3).

Table 1.

TaqMan PCR probes used for quantitative real-time RT-PCR assays

| Assay ID | Gene symbol | Gene name |

|---|---|---|

| Mm00455914_m1 | Bcl6b | B-cell CLL/lymphoma 6 member B protein |

| Mm01210866_m1 | Flt1 | Fms-related tyrosine kinase 1 |

| Mm00599849_m1 | Gdnf | Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor |

| Mm00833897_m1 | Gfra1 | Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor family receptor α1 |

| Mm01222419_m1 | Kdr | Kinase insert domain receptor |

| Mm02525720_s1 | Nanos2 | Nanos homolog 2 |

| Mm00437606_s1 | Neurog3 | Neurogenin 3 |

| Mm00435379_m1 | Nrp1 | Neuropilin 1 |

| Mm00803099_m1 | Nrp2 | Neuropilin 2 |

| Mm00475529_m1 | Rps2 | Mitochondrial ribosomal protein S2 |

| Mm00437304_m1 | Vegfa | VEGFA |

Immunohistochemistry of VEGF ligands and receptors

Immunohistochemistry was performed on paraffin-embedded testis tissue sections (5 μm thickness) obtained from normal C57BL/6 mice using the avidin-biotin complex method and sodium citrate antigen retrieval (10 mm sodium citrate, pH 6.0), as described (31). A list of affinity-purified primary antibodies (diluted in 10% normal serum, pH 7.4) is provided (Table 2). Immunoreactivity was detected using 3,3′-diaminobenzidine, and sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. As a negative control, serial sections were processed without primary antibody. At least three donors were used for each age and antigen evaluated (n ≥ 3).

Table 2.

List of antibodies used for immunohistochemical analysis

| Antigen | Antigen description | Dilution | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| DDX4 | Rabbit polyclonal to human DDX4/MVH | 1:500 | Abcama |

| FLT1 | Rabbit polyclonal to mouse FLT1 (C-17) | 1:400 | SCBTb |

| KDR | Mouse monoclonal to human KDR (A-3) | 1:400 | SCBTb |

| NRP1 | Rabbit monoclonal to human NRP1 (EPR3113) | 1:200 | Abcama |

| NRP2 | Rabbit monoclonal to human NRP2 (ab39067) | 1:200 | Abcama |

| VEGFA164 | Rabbit polyclonal to mouse VEGFA (A-20) | 1:200 | SCBTb |

| VEGFA165b | Mouse monoclonal to human VEGF 165b (MRVL56/1) | 1:200 | Abcama |

Abcam, Inc., Cambridge, MA.

Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA.

Analysis of VEGFR activation (phosphorylation) in vivo

Testis tissue obtained from neonatal and postnatal C57BL/6 mice was detunicated, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (in 10 mm PBS) at 4 C for 8 h followed by paraffin embedding and sectioning (5 μm thickness). After standard processing, heat-induced epitope retrieval with Tris-EDTA buffer [10 mm Tris Base, 1 mm EDTA solution, 0.05% Tween 20 (pH 9.0)] was used to unmask antigens before quenching endogenous peroxidase activity. After several washes in PBS, slides were blocked (10% normal serum vol/vol in PBS) for 30 min, incubated with affinity-purified antibodies to detect endogenous VEGFR signaling (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) for 12 h at 4 C. Briefly, sections were incubated with 1) rabbit polyclonal to the kinase active domain of human FLT1 (1:150; ab62183) phosphorylated at tyrosine 1333 (V-L-YP-S-T) (32), 2) rabbit polyclonal to activated catalytic domain of human KDR (1:150; ab63405) phosphorylated at tyrosine 1054 (d-I-YP-K-D) (33–35), and 3) rabbit polyclonal to activated human NRP1 (1:100; ab71766) phosphorylated at threonine T916 (LNTQS) (36, 37). After a series of washes, sections were processed with a biotinylated goat antirabbit secondary antibody for 60 min and then washed again and incubated with streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase substrate for 20 min at 25 C. Immunoreactivity was detected after a 2-min incubation in 3,3′-diaminobenzidine, and sections were lightly counterstained with hematoxylin. Sections of developing mouse kidney were processed as a positive control (data not shown). A negative control, serial sections were processed without primary antibody. Four donors were used for each age and antigen evaluated (n = 4).

Neonatal mice treatment

Neonatal mice were treated according to the methodology described by Gerber et al. (38), with minor modifications. Fifty-microliter glass syringes (Hamilton, Reno, NV) were used to administer all ip treatments (10 μl each). Briefly, A 30-gauge needle was inserted approximately 2–3 mm (commensurate with body wall thickness from P3–P5) into the lower right quadrant of the abdominal cavity at a 20° angle (to avoid the cecum and urinary bladder) and ensure rapid delivery of our various treatments. Neonatal mice (P3–P5) received a single, daily ip injection of vehicle (10 mm PBS plus 0.1% BSA), VEGFA164 (500 ng, wt/vol; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), or VEGFA165b (500 ng, wt/vol; R&D Systems) on P3, P4, and P5, respectively. To evaluate the effect of blocking VEGFA isoforms, we also treated neonatal mice with affinity-purified antibodies against VEGFA164 (1 μg, wt/vol; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), VEGFA165b (1 μg, wt/vol; Abcam), or rabbit IgG (1 μg, wt/vol; Vector Labortories, Burlingame, CA) within a similar timeframe. After treatment, Rosa26 mice were killed at P8 and P22, and testes were processed to obtain donor SSC for transplantation. In addition, we evaluated testicular growth and kinetics of germ and Sertoli cell proliferation in a group of C57BL/6 mice killed at 3 d (P8) and 17 d (P22) after treatment. Testes were also harvested from a subset of C57BL/6 mice at P8, P12, and P22 to determine the effect of treatments on the mRNA expression of factors associated with the biological activity of SSC.

Preparation of donor germ cells

Rosa26 donor testes were enzymatically digested as described by McLean (11), with minor modifications. Briefly, testis tissue was transferred to a dish containing digestion medium, which consisted of 0.18 mg/ml trypsin (GibcoBRL, Bethesda, MD) 0.16 mg/ml collagenase type IV (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO), and 0.6 mg/ml deoxyribonuclease (Sigma) in MEM α-medium (pH 7.4) and incubated for 10 min at 37 C. After incubation and addition of FBS (10% vol/vol), testis tissue digests were dispersed by gentle pipetting, and the resulting cell suspension was centrifuged at 600 × g for 7 min at 4 C. After several washes, donor cells were resuspended in MEM containing 0.03% trypan blue (GibcoBRL) to obtain spermatogonial stem cells for transplantation at a concentration of 107 cells/ml.

Germ cell transplantation and analysis of recipient testes

To determine stem cell activity, approximately 7.8 × 104 donor cells were transplanted into seminiferous tubules of busulfan-treated, immunologically compatible 129SvCP × C57BL/6 F1 hybrid recipient mice. When the infused volume deviated from 7 μl, the actual cell number injected was used for colonization efficiency calculations. Recipient mice were killed 8 wk after transplantation, and the colonization efficiency of Rosa26 SSC were determined by counting the number and length of blue colonies after staining with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indoyl β-d-galactoside.

Statistical analysis

All datasets are presented as the mean ± sem, and differences between ages and treatment groups were considered significant at P < 0.05. The effect of treatments on testis size, germ cell number, expression of SSC niche-associated factors, and stem cell activity were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA, and pairwise comparisons were evaluated with a Newman-Keuls multiple-range test. The effect of age on gene expression during testis development was also evaluated using ANOVA, and homogeneity of variance was determined using the Bartlett's test. Heteroscedastic datasets were analyzed using the Kruskal-Wallis test, and comparisons between groups were evaluated using the Dunn's multiple-comparison post hoc test (P < 0.05).

Results

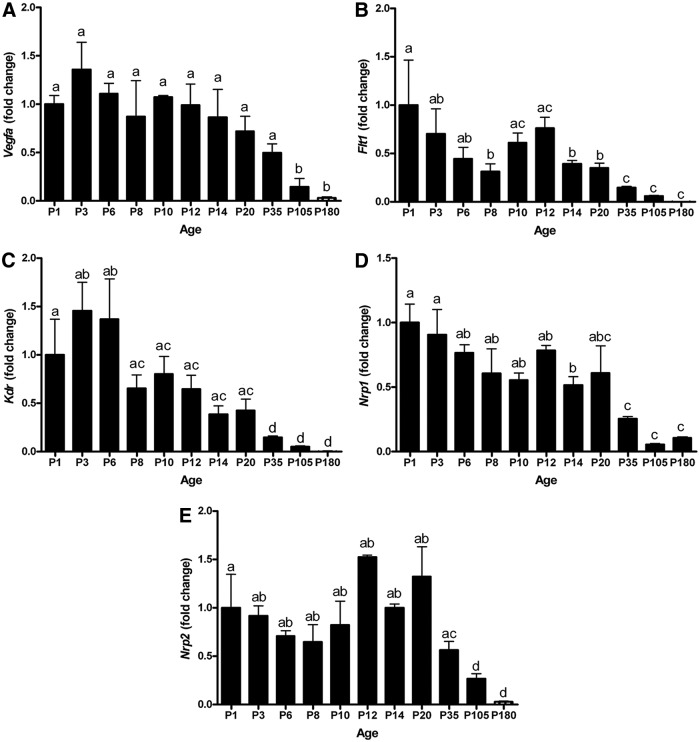

Gene expression of VEGF family molecules during mouse testis development

We assayed the expression of VEGF isoforms, receptors, and coreceptors during mouse testis development. The expression of each gene at each age was compared with the expression at P0 (day of birth), which was set at 1.0. This provides an accurate evaluation of gene expression during testis development for interpretation. The mouse ages selected for gene expression analysis coincided with the age when germ cell-initiated biological events occur, including migration and differentiation. Similarly, specific time points for somatic proliferation and differentiation were included to develop a complete understanding of the dynamics of testis development associated with VEGF signaling. Vegfa isoform expression was highest during early testis development until declining after P20 to P180 (Fig. 1A). Flt1 (vegfr1) expression was highest at birth and declined until P8, followed by an increase in expression at P10–P12 and then declining at P14 and remaining at this level throughout adulthood. Kdr (vegfr2) expression was highest during P1–P6, intermediate during P8–P20, and lowest from P20 throughout adulthood (Fig. 1C). Nrp1 was expressed at a stable level from birth until P20, followed by a 2- and 4-fold decrease at P35 and P105 that remained constant through P180 (Fig. 1D). Nrp2 was expressed in the neonatal testis from birth until P10 with a sharp increase at P12. Nrp2 expression subsequently declined 2-, 4-, and 6-fold from P20 until P35, P105, and P180, respectively, compared with its peak at P12 (Fig. 1E). The expression of VEGFA family molecules in the testis is present during the neonatal period concurrent with SSC formation and proliferation. The VEGFA primers did not distinguish between splice variant isoforms; thus, we conducted immunohistochemistry with antibodies specific for VEGFA164 and VEGFA165b, the two most biologically active isoforms.

Fig. 1.

Expression of VEGFA family isoforms, receptors, and coreceptors in mouse testes. Quantitative measurement (real-time RT-PCR) of mRNA of Vegfa (A), Flt1, (B) Kdr, (C), Nrp1, (D) and Nrp2 (E) from birth to adulthood. Data are representative of three independent experiments (n = 3), and different letters indicate significant differences between means (P < 0.05).

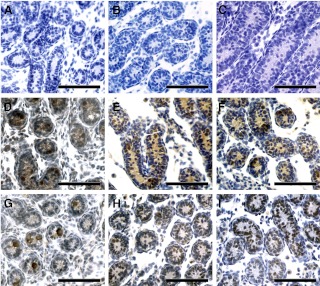

Protein expression of VEGF family molecules during mouse testis development

To determine the specific cells that express the VEGF isoforms, receptors, and coreceptors, we assayed with immunohistochemistry the expression of these proteins daily from birth until P22 in mouse testes. SSC form at P3 and initiate differentiation and proliferation between P5 and P8 (7), so we focused on precise analysis of VEGFA isoform expression in specific testicular cells at these ages. Comparison with negative controls (omission of primary antibody, Fig. 2, A–C) demonstrates that VEGFA164 expression was present in gonocytes and to a lesser degree in Sertoli cells at P3 (Fig. 2D) until P5 (Fig. 2E). From P5–P8, the expression of VEGFA164 was mainly in Sertoli cells (Fig. 2, E and F) with a marked reduction in germ cell expression compared with the first 5 d of life. This age coincides with gonocyte migration and formation of the SSC population. In contrast, VEGFA165b was more heterogeneous in expression during the P3–P5 period, being restricted to a distinct subset of gonocyte, undifferentiated spermatogonia, and Sertoli cell populations in the seminiferous tubules (Fig. 2, G–I). VEGFA165b was also present in primary spermatocytes and round spermatids at P20 (Supplemental Fig. 1G, published on The Endocrine Society's Journals Online web site at http://endo.endojournals.org).

Fig. 2.

VEGFA isoforms are expressed by germ and somatic cells during testis development. Immunohistochemical analysis of VEGFA164 (D–F) and VEGFA165b (G–I), protein expression in the testis tissue of P3, P5, and P8 mice. Omitting primary antibody served as a negative control in testis tissue (A–C). Four donors were used for each age and antigen evaluated. Scale bars, 50 μm.

FLT1 (VEGFR1) and KDR (VEGFR2) were remarkably similar in expression pattern within cell types that were positive for each protein. As can be seen in Supplemental Fig. 1, A–D, FLT1 and KDR were expressed in gonocytes at P3, spermatogonia at P5, and Sertoli cells. NRP1 was expressed by gonocytes and Sertoli cells at P3 (Supplemental Fig. 1E) and primarily localized to undifferentiated spermatogonia at P5 (Supplemental Fig. 1F) with continued expression in spermatogonia from P6–P20. FLT1 and KDR were also detected within testicular interstitial somatic cells throughout development, evidenced by uniform localization in populations of Leydig cells and spasmodic expression in lymphatic endothelial cells (Supplemental Fig. 1, A–D).

VEGFR signaling is active in germ and somatic cells during mouse testis development in vivo

VEGFA164/165b isoforms primarily elicit their effects on cell function after binding to KDR and FLT1, although signal transduction is more pronounced after KDR binding compared with FLT binding. Activation of KDR occurs via two independent pathways: VEGFA164/165b binds directly to KDR or VEGFA isoforms bind directly to NRP1, which presents the ligand to KDR after heterodimerization. Thus, after characterizing the patterns and cell-specific aspects of VEGF ligand and receptor mRNA and protein expression in vivo, we wanted to determine the specific cell types affected by VEGF signaling during neonatal testis development. To accomplish this goal, we used immunohistochemical analysis to detect the phosphorylation-specific expression of p-FLT1Y1333, p-KDRY1054, and p-NRP1T916 in germ and somatic cells during gonocyte maturation (P1–P5), SSC formation (P5–P6), and the first round of SSC expansion and self-renewal in vivo (P8–P14).

Endogenous FLT1 signaling detected by positive staining for p-FLT1Y1333 (the kinase active domain) was mainly localized to gonocytes at P1, but heterogeneous low-grade expression was also detected in Sertoli cells and interstitial Leydig cells (Supplemental Fig. 2D). When compared with P1, the activation of FLT1 signaling was greatly increased in somatic cells based on increased staining intensity for p-FLT1Y1333 in Sertoli cells, Leydig cells, and lymphatic endothelial cells at P3. Interestingly, activated FLT1 signaling was restricted to a subset of pericentrically localized gonocytes in the seminiferous tubules and a few lymphatic endothelial and Leydig cells from P3–P6 (Supplemental Fig. 2E). In contrast, the expression of p-FLT1Y1333 diminished in germ cells after gonocyte migration to the basement membrane and subsequent conversion into undifferentiated spermatogonia during P6–P8. Activation of FLT1 in germ cells did not occur after P8 until approximately P20 when positive staining for p-FLT1Y1333 was detected in type-B spermatogonia and preleptotene primary spermatocytes (Supplemental Fig. 2F). Thus, FLT1 signaling appears to be related to survival and migration of gonocytes and other differentiated germ cell types.

In contrast to FLT1, detection of KDR signaling in the testis after birth was variable. At P1, very few gonocytes expressed p-KDRY1054 (Supplemental Fig. 2G); however, this proportion increased by P3 (Supplemental Fig. 2H), the time period in which gonocytes resume proliferation. Sertoli cells from P1–P3 are positive for p-KDRY1054; however, by P5, Sertoli cells are negative, whereas undifferentiated spermatogonia are positive for p-KDRY1054 (Supplemental Fig. 2H). Activation of KDR in Sertoli cells occurs around P6 and remains strong until P8, when spermatogonia lose the positive signal for p-KDRY1054.

NRP1 signaling appears to be minimal within the seminiferous tubules after birth based on low staining intensity for p-NRP1T916 in gonocytes and Sertoli cells (Supplemental Fig. 2, J and K). Immunohistochemical analysis demonstrated that NRP1 activation in gonocytes, Sertoli cells, and undifferentiated spermatogonia occurs from P3–P8 (Supplemental Fig. 2K) and then declines until adulthood. NRP1 activation is rare by P14 and was observed in only approximately 5–6% of tubule cross-sections evaluated (one of 18), being localized and restricted to single undifferentiated spermatogonia in tubule cross-sections (Supplemental Fig. 2L).

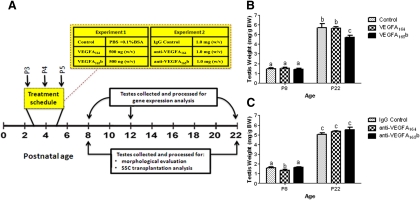

VEGF isoforms regulate testis development and the biological activity of undifferentiated germ cells in vivo

After assaying the expression pattern of VEGF family molecules and evaluating the timeline for VEGFR activation during neonatal testis development, we sought to determine the role of specific VEGF isoforms in regulating SSC cell fate decisions. To accomplish this objective, we used the approach of treating neonatal (P3–P5) mice in vivo using two experimental paradigms (Fig. 3A). Briefly, mice received daily ip injections of 1) control (vehicle alone; 10 mm PBS plus 0.1% BSA), VEGFA164 (500 ng, wt/vol), or VEGFA165b (500 ng, wt/vol) and 2) IgG control (1 μg, wt/vol), anti-VEGFA164 (1 μg, wt/vol), or anti-VEGFA165b (1 μg, wt/vol). It is known that a decline in testis weight indicates impaired cellular development or disruption of spermatogenesis in the postnatal testis. Thus after killing, body weight and paired testes weights were recorded at P8 and P22. When compared with vehicle alone, no difference in testis weight was detected at P8 after VEGFA164 or VEGFA165b treatment (Fig. 3B). However, we observed a significant reduction (P = 0.005) in testis weight when killed at P22 in mice treated with VEGFA165b from P3–P5 when compared with testis weights in control or VEGFA164 treatment groups. Moreover, inhibiting the biological activity of VEGFA164 with anti-VEGFA164 significantly decreased (P = 0.0242) testis weight at P8, when compared with IgG control or the anti-VEGFA165b treatment groups, respectively (Fig 3C). No differences in testis weight were detected when mice were evaluated at P22 (Fig 3C). Thus, VEGFA isoforms are likely important regulators of neonatal testis development in vivo.

Fig. 3.

VEGFA isoforms regulate mouse testis development in vivo. A, Diagram of the treatment schedule for experiments; B, testis weights of mice after VEGFA164, VEGFA165b, and control treatments; C, testis weights of mice after antibody treatments to block the biological activity of VEGFA164 and VEGFA165b in addition to treatment with nonspecific IgG as a control. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments (n ≥ 3), and different letters indicate significant differences between means (P < 0.05).

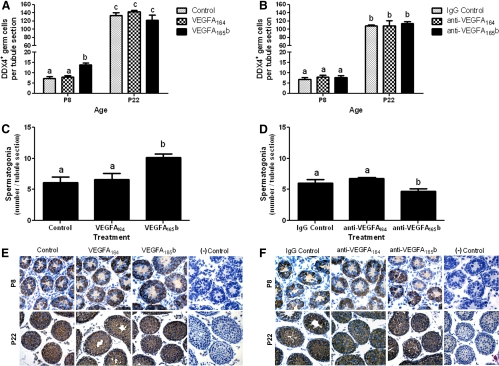

We also evaluated our treatment approach on the kinetics of germ and Sertoli cell proliferation and survival in a subset of mice by counting these cells at each biological endpoint. Regardless of treatment, no differences in Sertoli cell number were detected at P8–P22 (data not shown). We assayed the number of germ cells in testes from treated and control animals to determine whether treatment altered the initiation or pace of germ cell differentiation. Immunohistochemistry with an antibody for the germ cell-specific marker DEAD (Asp-Glu-Ala-Asp) box polypeptide 4 (DDX4) was used to count germ cells. DDX4 is expressed by all germ cells in developing testes providing a useful marker to determine whether changes in the SSC or undifferentiated spermatogonia population lead to changes in meiotic germ cells. Treating mice with VEGFA165b significantly increased the number of germ cells (DDX4+ cells) present at P8, but not P22, when compared with controls (Fig. 4A); a correlated increase in seminiferous tubule diameter was also observed (data not shown). Similarly, VEGFA165b treatment significantly increased the number of spermatogonia localized at the basement membrane at P8 (Fig. 4C), whereas blocking VEGFA165b activity with an antibody resulted in germ cell loss at P8 (Fig. 4D), suggesting a cytoprotective role for VEGFA165b. Thus, a balance with respect to the actions of VEGFA isoforms may be required to support the proliferation, maturation, and survival of undifferentiated spermatogonia. Light micrographs demonstrating immunohistochemical analysis of DDX+ cells in P8 and P22 testis tissue after in vivo treatment are provided (Fig. 4, E and F).

Fig. 4.

VEGFA isoforms regulate the biological activity of undifferentiated germ cells in vivo. Effect of VEGFA isoform ligand (A) and antibody (B) treatments daily from P3–P5 on the number of germ cells present in the testes of P8 and P22 mice. VEGFA isoform ligand (C) and antibody (D) treatments daily from P3–P5 on spermatogonial numbers present in the testes of P8. Germ cells were identified and counted with the use of immunohistochemical localization of DDX4, a germ cell-specific marker. E and F, Representative images of DDX4-stained testis tissue in P8 (E) and P22 (F) mice, respectively. Data are representative of three independent experiments (n = 3), and different letters indicate significant differences between means (P < 0.05). Scale bars, 50 μm.

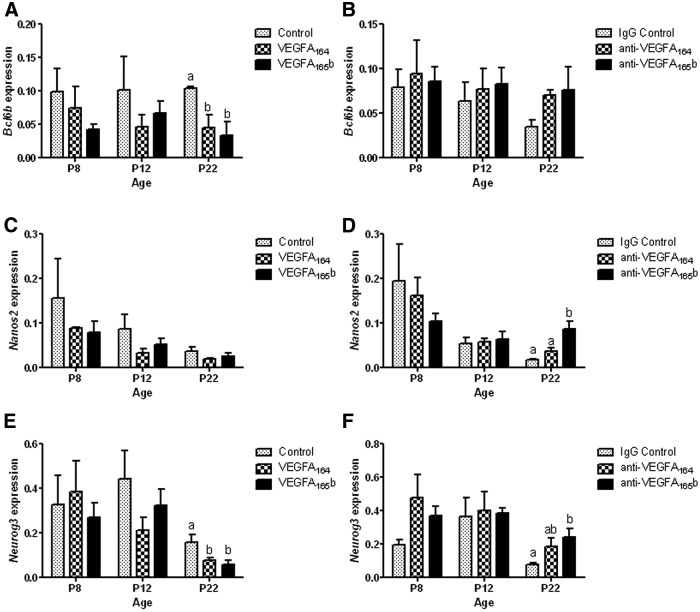

After treatments, mice were killed at P8, P12, and P22 and evaluated for several factors associated with SSC self-renewal (bcl6b and nanos2) and early differentiation (neurog3) with the use of qRT-PCR. TaqMan PCR assays were used to determine the in vivo effect of VEGFA isoform treatments on the mRNA expression of bcl6b, nanos2, and neurog3 in developing mouse testis tissue. Regardless of treatment, no significant differences were observed in bcl6b, nanos2, or neurog3 expression at P8 or P12 (Fig. 5, A–F). However, VEGFA164 and VEGFA165b treatments resulted in a significant decrease of bcl6b and neurog3 expression in vivo at P22 (Fig. 5A) compared with controls, whereas nanos2 expression was not affected (Fig. 5C). Blocking the activity of VEGFA165b isoforms (P < 0.05) increased nanos2 and neurog3 expression when compared with controls and anti-VEGFA164 groups at P22, respectively (Fig. 5, D and F). These data indicate that a balance between VEGFA isoform signal transduction may function to regulate the cell fate decisions of SSC to either self-renew or differentiate.

Fig. 5.

Effect of VEGFA isoform ligand (A, C, and E) and antibody (B, D, and F) treatments daily from P3–P5 on the expression of SSC niche-associated factors in P8, P12, and P22 mice, respectively. A–F, The normalized, mean expression values of Bcl6b (A and B), Nanos2 (C and D), and Neurog3 (E and F). Data are representative of at least three independent experiments, and different letters indicate significant differences between means (P < 0.05).

VEGF isoforms regulate in vivo SSC homeostasis after germ cell transplantation analysis

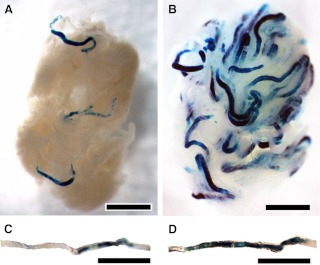

Germ cell transplantation analysis was used to determine the effect of VEGFA isoform treatments from P3–P5 on SSC formation at P8 and subsequent proliferation of the adult SSC population at P22. To accomplish this goal, testis tissue from VEGFA isoform and antibody-treated Rosa26+ mice were obtained at P8 and P22 and digested to obtain a single-cell suspension of germ cells for transplantation into the testis of infertile, busulfan-treated recipient mice (Fig. 6). Eight weeks after transplantation, recipient mice were killed, testes collected and stained with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indoyl β-d-galactoside, and the number of blue, donor-derived stem cell colonies was recorded (Fig. 6, A and B). In addition to calculating the number of SSC, we also assayed the postcolonization expansion rate of our donor-derived SSC to determine the effect of treatment on SSC self-renewal at P8 and maturation at P22, respectively (Fig. 6, C and D).

Fig. 6.

Representative images of recipient testes 8 wk after cell transplantation used to assay the effects of VEGFA ligand and antibody treatments daily from P3–P5 on regulating the biological activity of donor SSC. Light micrographs of recipient testes 8 wk after transplantation with SSC colony formation as indicated by areas of blue staining. A, Representative recipient testis with SSC colonization and donor-derived spermatogenesis after transplantation of germ cells at P8 after VEGFA165b treatment from P3–P5 in the donor mouse. Note the limited number of blue areas representing SSC colonization; B, representative recipient testis with SSC colonization after transplantation of germ cells at P8 after VEGFA164 treatment from P3–P5 in the donor mouse; C, a representative seminiferous tubule from a recipient testis with low rate of SSC expansion such as observed in the recipient testes transplanted with donor germ cells at P8 after VEGFA165b treatment; D, a representative seminiferous tubule from a recipient testis with a high rate of SSC expansion such as observed in the recipient testes transplanted with germ cells from P8 donor mice treated with the anti-VEGFA165b antibody. Data are representative of at least four independent experiments (n ≥ 4), and different letters indicate significant differences between means (P < 0.05). Scale bars, 0.5 mm (all panels).

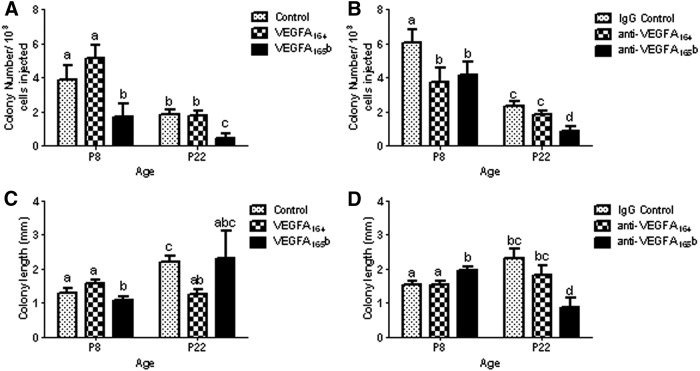

Germ cells obtained from VEGFA164-treated mice contained the same number of SSC as controls at P8 and P22, respectively (Fig. 7A). In contrast, in vivo VEGFA165b treatment significantly decreased the colonization efficiency of SSC, as evidenced by a 2-fold or greater reduction in donor-derived colonies detected at P8 and P22 (P ≤ 0.05), when compared with control and VEGFA164 treatments (Fig. 7A). Interestingly, donor germ cells harvested at P8 from mice treated with antibodies against VEGFA164 and VEGFA165b contained significantly less SSC than controls after 8 wk transplantation (Fig. 7B). However, a compensatory increase in the number of SSC obtained from mice treated with anti-VEGFA164 was detected by P22, based on the number of donor-derived colonies observed after transplantation (Fig. 7B). In contrast, the number of SSC in donor mice injected with anti-VEGFA165b remained significantly lower (P ≤ 0.05) than control and anti-VEGFA164-treated mice, respectively (Fig. 7B). These data indicate that VEGFA164 may be critical for SSC formation and self-renewal, whereas VEGFA165b likely regulates SSC differentiation and/or survival.

Fig. 7.

Effect of VEGFA family isoforms on colonization efficiency of donor-derived SSC originating from mice treated from P3–P5 and transplanted at either P8 or P22. Recipient testes were analyzed 8 wk after transplantation. A, SSC colony number in testes of recipient mice after VEGFA164, VEGFA165b, or control treatment; B, SSC colony number in testes of recipient mice after anti-VEGFA164 antibody, anti-VEGFA165b antibody treatment, or treatment with nonspecific IgG control; C and D, SSC colony growth and expansion after VEGFA164, VEGFA165b, or control treatment (C) and SSC colony growth and expansion after anti-VEGFA164 antibody, anti-VEGFA165b antibody treatment, or treatment with nonspecific IgG control (D). Data are representative of at least three independent experiments, and different letters indicate significant differences between means (P < 0.05).

Analysis of colony expansion demonstrated that VEGFA165b treatment decreased, whereas blocking VEGFA165b significantly increased the growth and expansion rate of P8 donor SSC when compared with controls and anti-VEGFA164 groups (Fig. 7, C and D). Conversely, donor SSC harvested from P22 mice treated with VEGFA164 demonstrated reduced colony growth following transplantation when compared with vehicle alone (Fig. 7C). Interestingly, blocking the activity of VEGFA165b produced similar effects in P22 donor SSC, evidenced by a 3-fold decrease in colony growth and expansion in reference to controls (Fig. 7D). This disparity suggests that a balancing act between VEGFA isoform signaling functions to regulate the cell-fate decisions of SSC in vivo. The results of transplantation indicate diverse roles for VEGFA isoform activity with respect to regulating SSC homeostasis in vivo.

Discussion

VEGFA, known for its role as a potent endothelial cell mitogen (22), has been implicated in a variety of nonvascular processes including neurogenesis (39–44), myogenesis (45–47), granulosa cell function (48–50), and testis development (15, 17, 51, 52). In humans, the VEGFA gene spans 16,272 bp of chromosome 6p12 and consists of eight exons (19). Alternative splicing of VEGFA yields proangiogenic isoforms (VEGFA111, VEGFA121, VEGFA145, VEGFA162, VEGFA165, VEGFA183, or VEGFA206) and antiangiogenic isoforms (VEGFA121b, VEGFA145b, VEGFA165b, VEGFA183b, or VEGFA189b) in regard to vascular development (19), but the role of these isoforms in nonvascular processes have yet to be elucidated. Accordingly, the complexity of VEGFA signal transduction in vivo increases because each of the 14 known VEGFA splice variants vary slightly in terms of biological activity, mechanism of receptor activation, and binding affinity for receptor/coreceptor interactions despite overlapping expression within a given cell type (19, 22, 32, 53–58).

Recent studies have found that SSC self-renewal, proliferation, and differentiation depend on the contributions of extrinsic and intrinsic factors modulated through the somatic cell niche (8). Identification of the network of factors regulating the biological activity of SSC is difficult due to the lack of specific SSC markers. As a result, in vivo treatment and transplantation studies are critical for a better understanding of the underlying mechanisms directing SSC cell fate.

In this study, we used qRT-PCR and immunohistochemical analysis to demonstrate the age- and cell-specific expression of the major VEGFA family ligands and receptors that coincide with specific events critical for germ cell development. The pattern of ligand expression we observed supports the hypothesis that autocrine and paracrine VEGFA production by germ and Sertoli cells is important for regulating SSC proliferation, self-renewal, and differentiation. Just as importantly, these ligands elicit their effects after binding to receptors FLT1 and KDR and the cofactor NRP1 in endothelial (22, 24, 57, 59–63) and nonvascular (37, 41, 44, 46, 49, 64–68) cell types. We demonstrate here differential expression of these receptors in gonocytes, undifferentiated spermatogonia, and Sertoli cells within the seminiferous epithelium during postnatal development. Due to the complex cell biology of the testis and activity of VEGFA isoforms, we also characterized the cell types affected by VEGFR signaling in situ, using phosphorylation-specific antibodies against the major intracellular kinase-active domains of FLT1, KDR, and NRP1. We observed robust FLT1 signal transduction in mitotically inactive and migrating gonocytes shortly after birth, implicating its inherent role in regulating gonocyte survival, proliferation, and migration. In contrast, strong KDR and NRP1 activation was restricted to proliferating gonocytes and undifferentiated spermatogonia present on the basement membrane from P3–P8, and NRP1 activation appears to be restricted to a small population of undifferentiated spermatogonia from P14 to adulthood. The Sertoli cell pattern of FLT1, KDR, and NRP1 activation correlates well with the differential expression of VEGFA ligands observed and, together with our germ cell data, support the hypothesis that VEGFA isoforms regulate SSC either directly or in concert with somatic niche cells.

Thus, we hypothesized that VEGFA family isoforms play an important role in regulating the cell fate decisions of SSC and used functional transplantation to test the effects of VEGFA164 or VEGFA165b, the two most potent pro- and antiangiogenic variants, on SSC self-renewal and differentiation in vivo. Based on colony number and growth rate after ligand and antibody treatment, we conclude that proangiogenic VEGFA164 supports SSC proliferation and self-renewal in mice, extending our findings in bulls (17). In contrast, when donor mice are treated with VEGFA165b, their SSC have a reduced capacity for proliferation and self-renewal. Similarly, treatment with VEGFA165b results in a larger number of spermatogonia present, demonstrating that VEGFA165b has a role in stimulating SSC differentiation to produce spermatogonia. Blocking VEGFA165b activity in mice resulted in a peculiar phenotype characterized by substantial loss of undifferentiated germ cells in situ and a smaller adult SSC population compared with controls. Thus, VEGFA165b signaling may also elicit a cytoprotective response in germ cells, similar to findings in the retinal epithelial cells (69). These data demonstrate VEGFA isoform regulation of SSC homeostasis likely requires a balancing act between proangiogenic and antiangiogenic variants. We recognize the potential for VEGFA treatments to elicit systemic effects on gonadotropin levels, such as FSH, that may modulate somatic cell populations. However, this is unlikely because no difference in Sertoli cell number was observed at any time points in the present study. Alteration of VEGFA isoform production from angiogenic to antiangiogenic isoforms could shift SSC from self-renewal to differentiation. These findings may have implications associated with accelerated loss of sperm production due to loss of SSC or precocious SSC differentiation. Investigation of cell-specific mechanisms that regulate alternative splicing in the testis and the specific mechanisms by which VEGFA treatment affects SSC fate decisions will be the focus of future in vitro studies.

Several studies have demonstrated the importance of GDNF for maintaining SSC survival and self-renewal (9, 10, 70) via activation of ret proto-oncogene (RET)Y1062 signaling (71). This is intriguing because GDNF expression appears to be weak in the postnatal testis in vivo based on publicly accessible microarray datasets (72) and is expressed in both germ and somatic cells in the seminiferous tubule (8). Interestingly, VEGF signaling has been shown to cross talk with the GDNF pathway in the developing kidney by inducing RETY1062 phosphorylation and up-regulation of GDNF expression (73) in a pattern suggesting a positive feedback loop exists for these growth factors. These observations, along with the pattern of VEGFA isoform and receptor expression by germ and somatic niche cells, suggest an intricate, multifactor network supporting the maintenance of SSC and the initiation of spermatogonia differentiation. To our knowledge, this is the first report of active VEGFR signaling detected in male germ cells, and more importantly, functional transplantation of SSC demonstrates that VEGFA isoforms regulate the cell fate decisions of SSC in vivo. The functional roles VEGFA splice variants and the complex partnerships between receptors leading to regulating the biological activity of SSC will be the focus of future experimentation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Nebraska Department of Health and Human Services Grant, 2009 (A.S.C. and D.J.M) and by NIH/NICHD HD051979 (A.S.C.). K.C.C. received support from an Achievement Rewards for Collegiate Scientists Fellowship.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- DDX4

- DEAD (Asp-Glu-Ala-Asp) box polypeptide 4

- FLT1

- fms-related tyrosine kinase 1

- GDNF

- glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor

- KDR

- kinase insert domain receptor

- NRP1

- neuropilin 1

- P1.5

- postnatal d 1.5

- qRT-PCR

- quantitative real-time RT-PCR

- RET

- ret proto-oncogene

- SSC

- spermatogonial stem cells

- VEGFA

- vascular endothelial growth factor A

- VEGFR

- VEGFA receptor.

References

- 1. de Rooij DG, Russell LD. 2000. All you wanted to know about spermatogonia but were afraid to ask. J Androl 21:776–798 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Peters H. 1970. Migration of gonocytes into the mammalian gonad and their differentiation. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 259:91–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Orth JM, Jester WF, Li LH, Laslett AL. 2000. Gonocyte-Sertoli cell interactions during development of the neonatal rodent testis. Curr Top Dev Biol 50:103–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McGuinness MP, Orth JM. 1992. Gonocytes of male rats resume migratory activity postnatally. Eur J Cell Biol 59:196–210 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McGuinness MP, Orth JM. 1992. Reinitiation of gonocyte mitosis and movement of gonocytes to the basement membrane in testes of newborn rats in vivo and in vitro. Anat Rec 233:527–537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Culty M. 2009. Gonocytes, the forgotten cells of the germ cell lineage. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today 87:1–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McLean DJ, Friel PJ, Johnston DS, Griswold MD. 2003. Characterization of spermatogonial stem cell maturation and differentiation in neonatal mice. Biol Reprod 69:2085–2091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Caires K, Broady J, McLean D. 2010. Maintaining the male germline: regulation of spermatogonial stem cells. J Endocrinol 205:133–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Meng X, Lindahl M, Hyvönen ME, Parvinen M, de Rooij DG, Hess MW, Raatikainen-Ahokas A, Sainio K, Rauvala H, Lakso M, Pichel JG, Westphal H, Saarma M, Sariola H. 2000. Regulation of cell fate decision of undifferentiated spermatogonia by GDNF. Science 287:1489–1493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Oatley JM, Avarbock MR, Telaranta AI, Fearon DT, Brinster RL. 2006. Identifying genes important for spermatogonial stem cell self-renewal and survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:9524–9529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McLean DJ. 2005. Spermatogonial stem cell transplantation and testicular function. Cell Tissue Res 322:21–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chiarini-Garcia H, Russell LD. 2001. High-resolution light microscopic characterization of mouse spermatogonia. Biol Reprod 65:1170–1178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chiarini-Garcia H, Raymer AM, Russell LD. 2003. Non-random distribution of spermatogonia in rats: evidence of niches in the seminiferous tubules. Reproduction 126:669–680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yoshida S, Sukeno M, Nabeshima Y. 2007. A vasculature-associated niche for undifferentiated spermatogonia in the mouse testis. Science 317:1722–1726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bott RC, McFee RM, Clopton DT, Toombs C, Cupp AS. 2006. Vascular endothelial growth factor and kinase domain region receptor are involved in both seminiferous cord formation and vascular development during testis morphogenesis in the rat. Biol Reprod 75:56–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bott RC, Clopton DT, Cupp AS. 2008. A proposed role for VEGF isoforms in sex-specific vasculature development in the gonad. Reprod Domest Anim 43(Suppl 2):310–316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Caires KC, de Avila J, McLean DJ. 2009. Vascular endothelial growth factor regulates germ cell survival during establishment of spermatogenesis in the bovine testis. Reproduction 138:667–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schmidt JA, de Avila JM, McLean DJ. 2006. Effect of vascular endothelial growth factor and testis tissue culture on spermatogenesis in bovine ectopic testis tissue xenografts. Biol Reprod 75:167–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Harper SJ, Bates DO. 2008. VEGF-A splicing: the key to anti-angiogenic therapeutics? Nat Rev Cancer 8:880–887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Byrne AM, Bouchier-Hayes DJ, Harmey JH. 2005. Angiogenic and cell survival functions of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). J Cell Mol Med 9:777–794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yamazaki Y, Morita T. 2006. Molecular and functional diversity of vascular endothelial growth factors. Mol Divers 10:515–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cébe-Suarez S, Zehnder-Fjällman A, Ballmer-Hofer K. 2006. The role of VEGF receptors in angiogenesis; complex partnerships. Cell Mol Life Sci 63:601–615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bates DO, Cui TG, Doughty JM, Winkler M, Sugiono M, Shields JD, Peat D, Gillatt D, Harper SJ. 2002. VEGF165b, an inhibitory splice variant of vascular endothelial growth factor, is down-regulated in renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Res 62:4123–4131 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Woolard J, Wang WY, Bevan HS, Qiu Y, Morbidelli L, Pritchard-Jones RO, Cui TG, Sugiono M, Waine E, Perrin R, Foster R, Digby-Bell J, Shields JD, Whittles CE, Mushens RE, Gillatt DA, Ziche M, Harper SJ, Bates DO. 2004. VEGF165b, an inhibitory vascular endothelial growth factor splice variant: mechanism of action, in vivo effect on angiogenesis and endogenous protein expression. Cancer Res 64:7822–7835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cui TG, Foster RR, Saleem M, Mathieson PW, Gillatt DA, Bates DO, Harper SJ. 2004. Differentiated human podocytes endogenously express an inhibitory isoform of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF165b) mRNA and protein. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 286:F767–F773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Konopatskaya O, Churchill AJ, Harper SJ, Bates DO, Gardiner TA. 2006. VEGF165b, an endogenous C-terminal splice variant of VEGF, inhibits retinal neovascularization in mice. Mol Vis 12:626–632 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Qiu Y, Ferguson J, Oltean S, Neal CR, Kaura A, Bevan H, Wood E, Sage LM, Lanati S, Nowak DG, Salmon AH, Bates D, Harper SJ. 2010. Overexpression of VEGF165b in podocytes reduces glomerular permeability. J Am Soc Nephrol 21:1498–1509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hua J, Spee C, Kase S, Rennel ES, Magnussen AL, Qiu Y, Varey A, Dhayade S, Churchill AJ, Harper SJ, Bates DO, Hinton DR. 2010. Recombinant human VEGF165b inhibits experimental choroidal neovascularization. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 51:4282–4288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bevan HS, van den Akker NM, Qiu Y, Polman JA, Foster RR, Yem J, Nishikawa A, Satchell SC, Harper SJ, Gittenberger-de Groot AC, Bates DO. 2008. The alternatively spliced anti-angiogenic family of VEGF isoforms VEGFxxxb in human kidney development. Nephron Physiol 110:p57–p67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Muller PY, Janovjak H, Miserez AR, Dobbie Z. 2002. Processing of gene expression data generated by quantitative real-time RT-PCR. Biotechniques 32:1372–1374, 1376,, 1378–1379 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Caires KC, Schmidt JA, Oliver AP, de Avila J, McLean DJ. 2008. Endocrine regulation of the establishment of spermatogenesis in pigs. Reprod Domest Anim 43(Suppl 2):280–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ito N, Huang K, Claesson-Welsh L. 2001. Signal transduction by VEGF receptor-1 wild type and mutant proteins. Cell Signal 13:849–854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Takahashi T, Yamaguchi S, Chida K, Shibuya M. 2001. A single autophosphorylation site on KDR/Flk-1 is essential for VEGF-A-dependent activation of PLC-γ and DNA synthesis in vascular endothelial cells. EMBO J 20:2768–2778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dougher M, Terman BI. 1999. Autophosphorylation of KDR in the kinase domain is required for maximal VEGF-stimulated kinase activity and receptor internalization. Oncogene 18:1619–1627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kendall RL, Rutledge RZ, Mao X, Tebben AJ, Hungate RW, Thomas KA. 1999. Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor KDR tyrosine kinase activity is increased by autophosphorylation of two activation loop tyrosine residues. J Biol Chem 274:6453–6460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Glinka Y, Prud'homme GJ. 2008. Neuropilin-1 is a receptor for transforming growth factor β-1, activates its latent form, and promotes regulatory T cell activity. J Leukoc Biol 84:302–310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Saban MR, Sferra TJ, Davis CA, Simpson C, Allen A, Maier J, Fowler B, Knowlton N, Birder L, Wu XR, Saban R. 2010. Neuropilin-VEGF signaling pathway acts as a key modulator of vascular, lymphatic, and inflammatory cell responses of the bladder to intravesical BCG treatment. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 299:F1245–F1256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gerber HP, Hillan KJ, Ryan AM, Kowalski J, Keller GA, Rangell L, Wright BD, Radtke F, Aguet M, Ferrara N. 1999. VEGF is required for growth and survival in neonatal mice. Development 126:1149–1159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Schratzberger P, Schratzberger G, Silver M, Curry C, Kearney M, Magner M, Alroy J, Adelman LS, Weinberg DH, Ropper AH, Isner JM. 2000. Favorable effect of VEGF gene transfer on ischemic peripheral neuropathy. Nat Med 6:405–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fantin A, Maden CH, Ruhrberg C. 2009. Neuropilin ligands in vascular and neuronal patterning. Biochem Soc Trans 37:1228–1232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. McLennan R, Teddy JM, Kasemeier-Kulesa JC, Romine MH, Kulesa PM. 2010. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) regulates cranial neural crest migration in vivo. Dev Biol 339:114–125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wada T, Haigh JJ, Ema M, Hitoshi S, Chaddah R, Rossant J, Nagy A, van der Kooy D. 2006. Vascular endothelial growth factor directly inhibits primitive neural stem cell survival but promotes definitive neural stem cell survival. J Neurosci 26:6803–6812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Nishijima K, Ng YS, Zhong L, Bradley J, Schubert W, Jo N, Akita J, Samuelsson SJ, Robinson GS, Adamis AP, Shima DT. 2007. Vascular endothelial growth factor-A is a survival factor for retinal neurons and a critical neuroprotectant during the adaptive response to ischemic injury. Am J Pathol 171:53–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ara J, Fekete S, Zhu A, Frank M. 2010. Characterization of neural stem/progenitor cells expressing VEGF and its receptors in the subventricular zone of newborn piglet brain. Neurochem Res 35:1455–1470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Germani A, Di Carlo A, Mangoni A, Straino S, Giacinti C, Turrini P, Biglioli P, Capogrossi MC. 2003. Vascular endothelial growth factor modulates skeletal myoblast function. Am J Pathol 163:1417–1428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Banerjee S, Mehta S, Haque I, Sengupta K, Dhar K, Kambhampati S, Van Veldhuizen PJ, Banerjee SK. 2008. VEGF-A165 induces human aortic smooth muscle cell migration by activating neuropilin-1-VEGFR1-PI3K axis. Biochemistry 47:3345–3351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bryan BA, Walshe TE, Mitchell DC, Havumaki JS, Saint-Geniez M, Maharaj AS, Maldonado AE, D'Amore PA. 2008. Coordinated vascular endothelial growth factor expression and signaling during skeletal myogenic differentiation. Mol Biol Cell 19:994–1006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Yamamoto S, Konishi I, Tsuruta Y, Nanbu K, Mandai M, Kuroda H, Matsushita K, Hamid AA, Yura Y, Mori T. 1997. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) during folliculogenesis and corpus luteum formation in the human ovary. Gynecol Endocrinol 11:371–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Greenaway J, Connor K, Pedersen HG, Coomber BL, LaMarre J, Petrik J. 2004. Vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptor, Flk-1/KDR, are cytoprotective in the extravascular compartment of the ovarian follicle. Endocrinology 145:2896–2905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Shimizu T, Jayawardana BC, Nishimoto H, Kaneko E, Tetsuka M, Miyamoto A. 2006. Hormonal regulation and differential expression of neuropilin (NRP)-1 and NRP-2 genes in bovine granulosa cells. Reproduction 131:555–559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Korpelainen EI, Karkkainen MJ, Tenhunen A, Lakso M, Rauvala H, Vierula M, Parvinen M, Alitalo K. 1998. Overexpression of VEGF in testis and epididymis causes infertility in transgenic mice: evidence for nonendothelial targets for VEGF. J Cell Biol 143:1705–1712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Rudolfsson SH, Wikström P, Jonsson A, Collin O, Bergh A. 2004. Hormonal regulation and functional role of vascular endothelial growth factor A in the rat testis. Biol Reprod 70:340–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Poltorak Z, Cohen T, Neufeld G. 2000. The VEGF splice variants: properties, receptors, and usage for the treatment of ischemic diseases. Herz 25:126–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Gluzman-Poltorak Z, Cohen T, Herzog Y, Neufeld G. 2000. Neuropilin-2 is a receptor for the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) forms VEGF-145 and VEGF-165 [corrected]. J Biol Chem [Erratum (2000) 275:29922] 275:18040–18045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Matsumoto T, Claesson-Welsh L. 2001. VEGF receptor signal transduction. Sci STKE 2001:re21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Whitaker GB, Limberg BJ, Rosenbaum JS. 2001. Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 and neuropilin-1 form a receptor complex that is responsible for the differential signaling potency of VEGF165 and VEGF121. J Biol Chem 276:25520–25531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zachary I. 2003. VEGF signalling: integration and multi-tasking in endothelial cell biology. Biochem Soc Trans 31:1171–1177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Otrock ZK, Makarem JA, Shamseddine AI. 2007. Vascular endothelial growth factor family of ligands and receptors: review. Blood Cells Mol Dis 38:258–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Nowak DG, Woolard J, Amin EM, Konopatskaya O, Saleem MA, Churchill AJ, Ladomery MR, Harper SJ, Bates DO. 2008. Expression of pro- and anti-angiogenic isoforms of VEGF is differentially regulated by splicing and growth factors. J Cell Sci 121:3487–3495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Neufeld G, Kessler O, Herzog Y. 2002. The interaction of Neuropilin-1 and neuropilin-2 with tyrosine-kinase receptors for VEGF. Adv Exp Med Biol 515:81–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Mineur P, Colige AC, Deroanne CF, Dubail J, Kesteloot F, Habraken Y, Noël A, Vöö S, Waltenberger J, Lapière CM, Nusgens BV, Lambert CA. 2007. Newly identified biologically active and proteolysis-resistant VEGF-A isoform VEGF111 is induced by genotoxic agents. J Cell Biol 179:1261–1273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Wang L, Zeng H, Wang P, Soker S, Mukhopadhyay D. 2003. Neuropilin-1-mediated vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor-dependent endothelial cell migration. J Biol Chem 278:48848–48860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Nakatsu MN, Sainson RC, Pérez-del-Pulgar S, Aoto JN, Aitkenhead M, Taylor KL, Carpenter PM, Hughes CC. 2003. VEGF121 and VEGF165 regulate blood vessel diameter through vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 in an in vitro angiogenesis model. Lab Invest 83:1873–1885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Yang Q, McHugh KP, Patntirapong S, Gu X, Wunderlich L, Hauschka PV. 2008. VEGF enhancement of osteoclast survival and bone resorption involves VEGF receptor-2 signaling and beta3-integrin. Matrix Biol 27:589–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Muthusamy A, Cooper CR, Gomes RR., Jr 2010. Soluble perlecan domain I enhances vascular endothelial growth factor-165 activity and receptor phosphorylation in human bone marrow endothelial cells. BMC Biochem 11:43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Bellon A, Luchino J, Haigh K, Rougon G, Haigh J, Chauvet S, Mann F. 2010. VEGFR2 (KDR/Flk1) signaling mediates axon growth in response to semaphorin 3E in the developing brain. Neuron 66:205–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Zhang S, Zhau HE, Osunkoya AO, Iqbal S, Yang X, Fan S, Chen Z, Wang R, Marshall FF, Chung LW, Wu D. 2010. Vascular endothelial growth factor regulates myeloid cell leukemia-1 expression through neuropilin-1-dependent activation of c-MET signaling in human prostate cancer cells. Mol Cancer 9:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Mac Gabhann F, Popel AS. 2007. Interactions of VEGF isoforms with VEGFR-1, VEGFR-2, and neuropilin in vivo: a computational model of human skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 292:H459–H474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Magnussen AL, Rennel ES, Hua J, Bevan HS, Beazley Long N, Lehrling C, Gammons M, Floege J, Harper SJ, Agostini HT, Bates DO, Churchill AJ. 2010. VEGF-A165b is cytoprotective and antiangiogenic in the retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 51:4273–4281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Wu X, Oatley JM, Oatley MJ, Kaucher AV, Avarbock MR, Brinster RL. 2010. The POU domain transcription factor POU3F1 is an important intrinsic regulator of GDNF-induced survival and self-renewal of mouse spermatogonial stem cells. Biol Reprod 82:1103–1111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Jijiwa M, Kawai K, Fukihara J, Nakamura A, Hasegawa M, Suzuki C, Sato T, Enomoto A, Asai N, Murakumo Y, Takahashi M. 2008. GDNF-mediated signaling via RET tyrosine 1062 is essential for maintenance of spermatogonial stem cells. Genes to Cells 13:365–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Shima JE, McLean DJ, McCarrey JR, Griswold MD. 2004. The murine testicular transcriptome: characterizing gene expression in the testis during the progression of spermatogenesis. Biol Reprod 71:319–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Tufro A, Teichman J, Banu N, Villegas G. 2007. Crosstalk between VEGF-A/VEGFR2 and GDNF/RET signaling pathways. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 358:410–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.