Abstract

Shortly before ovulation, the oocyte acquires developmental competence and granulosa cells undergo tremendous changes including cumulus expansion and luteinization. Zinc is emerging as a key regulator of meiosis in vitro, but a complete understanding of zinc-mediated effects during the periovulatory period is lacking. The present study uncovers the previously unknown role of zinc in maintaining meiotic arrest before ovulation. A zinc chelator [N,N,N′,N′-tetrakis (2-pyridylmethyl) ethylenediamine (TPEN)] caused premature germinal vesicle breakdown and associated spindle defects in denuded oocytes even in the presence of a phosphodiesterase 3A inhibitor (milrinone). TPEN also potently blocked cumulus expansion by blocking induction of expansion-related transcripts Has2, Ptx3, Ptgs2, and Tnfaip6 mRNA. Both meiotic arrest and cumulus expansion were rescued by exogenous zinc. Lack of cumulus expansion is due to an almost complete suppression of phospho-Sma- and Mad-related protein 2/3 signaling. Consistent with a decrease in phospho-Sma- and Mad-related protein 2/3 signaling, TPEN also decreased cumulus transcripts (Ar and Slc38a3) and caused a surprising increase in mural transcripts (Lhcgr and Cyp11a1) in cumulus cells. In vivo, feeding a zinc-deficient diet for 10 d completely blocked ovulation and compromised cumulus expansion. However, 42.5% of oocytes had prematurely resumed meiosis before human chorionic gonadotropin injection, underscoring the importance of zinc before ovulation. A more acute 3-d treatment with a zinc-deficient diet did not block ovulation but did increase the number of oocytes trapped in luteinizing follicles. Moreover, 23% of ovulated oocytes did not reach metaphase II due to severe spindle defects. Thus, acute zinc deficiency causes profound defects during the periovulatory period with consequences for oocyte maturation, cumulus expansion, and ovulation.

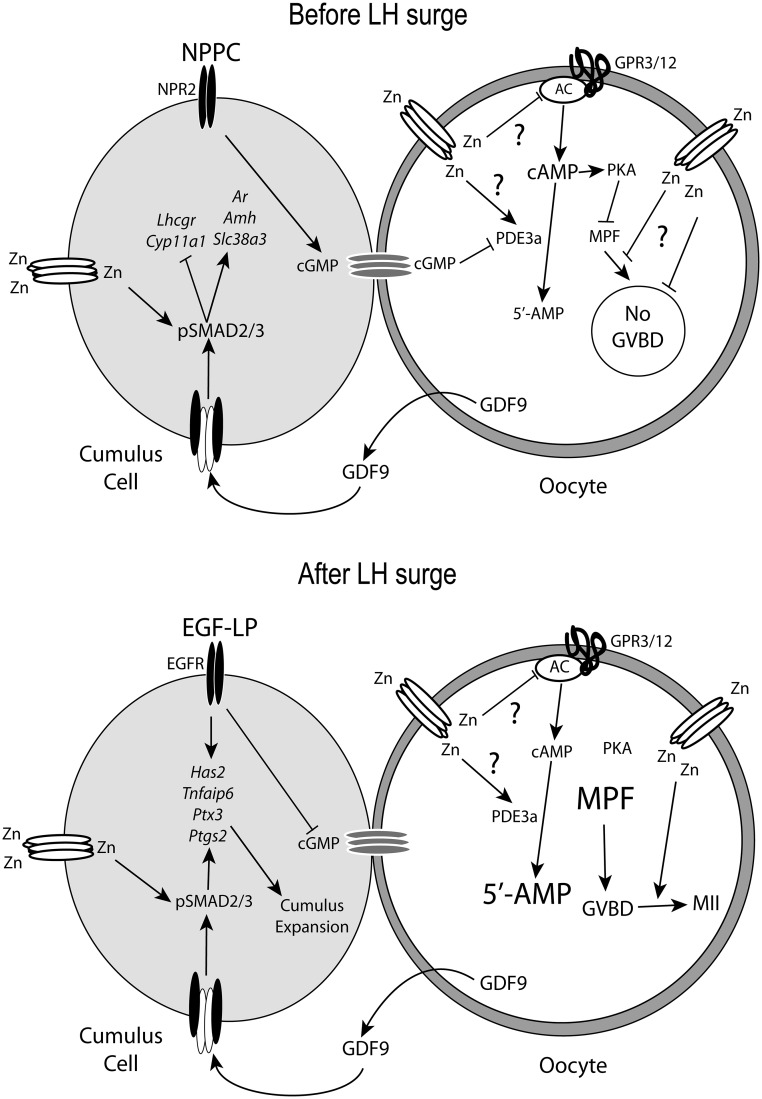

The periovulatory period is a critical transition during follicular development. Until just before ovulation, the oocyte is held in prophase I arrest by the combined action of mural and cumulus granulosa cells. Mural cells produce natriuretic peptide precursor C, which binds to a receptor (natriuretic peptide receptor 2) on the cumulus cells to increase cGMP production (1). Gap junctions mediate the transfer of cGMP from cumulus cells to the oocyte where cGMP inhibits phosphodiesterase 3A (PDE3A) activity to block cAMP breakdown (2, 3). Oocytes also express two G protein-coupled receptors (GPR), GPR3 and GPR12, which generate cAMP in the oocyte (4, 5). The combined effects of GPR3 and GPR12 activity and suppressed PDE3 activity maintain high intra-oocyte cAMP and protein kinase A (PKA) levels. PKA blocks activation of maturation-promoting factor (MPF), composed of cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (CDK1)/cyclin B1, thus preventing germinal vesicle breakdown (GVBD). In the somatic compartment, granulosa cells are divided into mural or cumulus cell lineages depending on the local microenvironment. There is no vasculature inside the basement membrane separating granulosa and theca cell layers. Granulosa cells along the periphery of the follicle are exposed to higher concentrations of FSH and develop a mural cell phenotype with high levels of Lhcgr and Cyp11a1 mRNA (6, 7). The granulosa cells around the oocyte are under direct stimulation of oocyte secreted factors acting, in large part, through phospho-Sma- and Mad-related proteins, pSMAD2/3 (6) and pSMAD1/5/9 (8) signaling pathways to stimulate the cumulus phenotype. Oocyte factors promote increased glycolysis (8, 9), cholesterol synthesis (10), amino acid transport (11), expansion (6, 12, 13), and expression of cumulus marker transcripts, including Ar, Amh, Slc38a3, and Egfr, and suppression of mural transcripts (Lhcgr and Cyp11a1) in cumulus cells (6, 14).

The LH surge initiates changes in the follicle that include oocyte maturation, cumulus expansion, and ultimately ovulation and luteinization. LH activates the PKA/cAMP pathway to induce epidermal growth factor (EGF)-like peptides (EGF-LP) from mural granulosa cells, which in turn transmit and amplify the ovulatory signal throughout the follicle by auto-amplification of EGF-LP in mural and cumulus cells (15–18). This is critical because mouse cumulus cells do not express Lhcgr mRNA (LH receptor) (6, 7). Activation of the EGF receptor by EGF-LP decreases cumulus cell cGMP production and closes gap junctions, thus lowering cGMP levels in the oocyte and promoting PDE3A activation. PDE3A will then degrade cAMP and inactivate PKA, which allows activation of MPF (2, 18–20). MPF mediates GVBD and meiotic progression until metaphase II. In cumulus cells, EGF receptor activation of MAPK3/1 in conjunction with oocyte-stimulated pSMAD2/3 signaling induces expansion-related transcripts (Has2, Ptgs2, Ptx3, and Tnfaip6) and cumulus expansion (21–24). Thus, LH-induced signals initiate a cascade of events to promote both cumulus expansion and oocyte maturation.

Zinc is a transition metal important for reproduction. In males, zinc deficiency leads to poor semen quality, impaired sperm motility, abnormal head morphology, and reduced number of viable sperm (25–27). In females, dietary zinc deficiency causes developmental problems throughout pregnancy (28–30). Prolonged zinc deficiency in rabbits causes decreased mating frequency and lack of corpus luteum (CL) formation (31). Recently, a role for zinc in the completion of meiosis I was demonstrated in vitro (32–34). However, the zinc-dependent mechanisms controlling cumulus cell function and oocyte development during the periovulatory period are largely unknown. In this study, using in vitro and in vivo methods, we uncover dramatic effects of acute zinc deficiency on cumulus expansion, ovulation, and regulation of GVBD.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Female CD1 mice (Mus musculus) were obtained from the research colony of the investigators. For in vitro experiments, ovaries were collected from 21-d-old mice 48 h after ip injection of 5 IU pregnant mare serum gonadotropin (PMSG) (National Hormone and Peptide Program, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Torrance, CA). For in vivo experiments, animals (18 d) were weaned and fed treatment diets as described below. Animals were maintained according to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Institute for Learning and Animal Research). All animal use was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at The Pennsylvania State University.

In vitro culture of cumulus-oocyte complexes (COC) and oocytes

COC were collected from PMSG-primed mice (48 h). Ovaries were collected aseptically and placed in MEM-α (Life Technologies, Inc., Grand Island, NY) with Earle's salts, 75 mg/liter penicillin G, 50 mg/liter streptomycin sulfate, 0.23 mm pyruvate, and 3 mg/ml BSA. COC were released from antral follicles by gentle puncture with a syringe and needle. Fully grown denuded oocytes were isolated from COC by gentle pipetting to remove the cumulus cells. To prevent spontaneous resumption of meiosis, some oocytes and COC were cultured in the presence of the PDE3A-specific inhibitor milrinone (10 μm). In some experiments, oocytes and COC were exposed to the membrane-permeable transition metal chelator N,N,N′,N′-tetrakis (2-pyridylmethyl) ethylenediamine (TPEN). Fully grown denuded oocytes (two oocytes per microliter) or COC (one COC per microliter) were cultured for 4–20 h as indicated in the figure legends. For expansion experiments, COC were cultured in bicarbonate-buffered MEM-α plus 10% fetal bovine serum in the following groups: control, EGF (10 ng/ml), TPEN (10 μm), EGF plus TPEN, or EGF plus TPEN and zinc (10 μm) for 15 h. For measuring expansion transcripts, COC were cultured for 6 and 10 h, and COC were then frozen until RNA isolation.

Histology

For histological analysis, ovaries were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. Ovarian sections (5 μm) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin using standard methods.

Immunofluorescence

Oocytes were fixed in microtubule-stabilizing buffer (2.5 mm EGTA, 5 mm MgCl2, 0.1 mm PIPES, 2% paraformaldehyde, and 2.5 mm Triton X-100) for 30 min at 37 C. After fixing, oocytes were washed (three times) in PBS with Tween 20 (PBST) (1% BSA) and blocked in goat serum blocking buffer (PBS, 2% goat serum, 1% BSA, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 0.05% Tween 20) for 50 min at 37 C followed immediately by incubation with anti-α-tubulin (1:200; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO), anti-γ-tubulin (1:200; Sigma), anti-trimethylated histone H3K4 (1:400; Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA) and anti-acetylated histone H4K9 (1:200; Cell Signaling Technology) for 50 min at 37 C. After washing (three times) in PBST, oocytes were incubated with goat antimouse IgG Alexa Fluor 488 (1:1000; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) and phalloidin-tetraethylrhodamine isothiocyanate (TRITC) (10 μg/ml; Sigma) for 30 min at 37 C followed by washing (three times) with PBST. Oocytes were mounted in 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) anti-fade gold (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) on glass slides with etched rings to prevent oocytes from being ruptured by the coverslip. Slides were imaged with an epifluorescent microscope (AxioScope 2 Plus; Leica, Bannockburn, IL) and a DP20 Olympus digital color camera and DP software or by confocal microscopy using an Olympus Fluoview 1000 confocal microscope.

cAMP assay

Groups of 200–250 oocytes were cultured in medium with or without TPEN (10 μm) for 6 or 10 h. At the end of each incubation period, samples were lysed in 100 μl 0.1 m HCl on ice for 10 min and stored in −80 C until analyzed for cAMP content. All samples and standards were acetylated and intracellular concentration of cAMP was determined by EIA kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Cayman Chemical Co., Ann Arbor, MI).

MPF kinase assay

The CDK1 (cell division and control 2) kinase assay was performed as described by Ito and colleagues (35) using the MESACUP CDK1 kinase assay kit (MBL International, Woburn, MA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 10 mouse oocytes were collected at each time point and lysed in 5 μl kinase sample buffer, containing 50 mm Tris (pH 7.5), 5 mm EDTA, 0.5 m NaCl, 50 mm 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.01% Brij 35, 25 mm β-glycerophosphate, 1 mm Na3VO4, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 50 μg/ml leupeptin. The lysates were incubated with 45 μl kinase assay buffer containing 25 mm HEPES buffer (pH 7.5), 10 mm MgCl2 (MBL), 10% (vol/vol) mouse vimentin peptide solution (SLYSSPGGAYC), and 0.1 mm ATP (Sigma) for 30 min at 30 C. Phosphorylated mouse vimentin peptide was detected by ELISA, which is contained in the kit. Results are expressed as OD at 492 nm. Three independent groups of oocytes were analyzed in duplicate. GV and metaphase II (MII) oocytes served as reference samples for cells with low and high MPF activity, respectively.

Western blotting

Thirty-five COC were treated with control medium or TPEN (10 μm) for 6 h (pSMAD2) or with control medium, EGF (10 ng/ml), TPEN (10 μm), and EGF plus TPEN for 4 h (pMAPK3/1). Samples were denatured and prepared for Western blotting as previously described (22). Primary antibodies used were rabbit anti-pSMAD2 (1:500; Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit anti-β-actin (1:5000; Sigma), and rabbit anti-pMAPK3/1 (1:1000; Sigma). The secondary antibody used was a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat antirabbit (1:2000; Invitrogen).

Total RNA isolation and quantitative PCR

Total RNA was isolated from COC using the RNeasy micro kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA). Total RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using the Quantitek cDNA synthesis kit (QIAGEN). Quantification of cumulus and mural cell transcripts was conducted using gene-specific primers (Table 1) by the 2−ΔΔCt method using Rpl19 as the normalizer as described previously (36, 37). Only one product of the appropriate size was identified for each set of primers, and all amplification products were sequenced to confirm specificity.

Table 1.

Primer sequences used for quantitative PCR

| Gene symbol | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| Amh | AGCTGGACACCATGCCTTT | TTCGAAGCCTGGGTCAGA |

| Has2 | GACCCTATGGTTGGAGGTGTT | ATAAGACTGGCAGGCCCTTT |

| Lhcgr | GGATAGAAGCTAATGCCTTTGACAAC | TAAAAGCACCGGGTTCAATGTATAG |

| Ptgfr | GCAGATCTCACCACCTGGA | CACTGGGGAATTATTTCCATTTATT |

| Ptgs2 | TCCATTGACCAGAGCAGAGA | TTCTGCAGCCATTTCCTTCT |

| Ptx3 | TGGCTGAGACCTCGGATGAC | GCGAGTTCTCCAGCATGATGA |

| Tnfaip6 | GAACATGATCCAGGCTGCTT | GGTCATGACATTTCCTGTGCT |

| Rpl19 | TTCAAAAACAAGCGCATCCT | CTTTCGTGCTTCCTTGGTCT |

All primers are 5′ to 3′.

Zinc-deficient diet (ZDD)

To investigate effects of acute zinc deficiency in vivo on periovulatory ovarian function, 18-d-old weaned mice were housed on wire-bottom racks in polycarbonate cages and given a control diet (29 mg zinc/kg) based on American Institute of Nutrition 76 or a ZDD based on the control diet with zinc supplement omitted (<1 mg zinc/kg) for 3 or 10 d. Diets were purchased from MP Biomedicals (Solon, OH). Animals were primed with PMSG 48 h before the end of treatment. Oocytes and ovaries were collected on d 3 and 10 from four to five animals per group. A separate group of animals were treated as above except they received an ovulatory dose of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) (5 IU) on d 3 or 10. Oocytes and ovaries were collected 13 h later from four to five animals per group.

Statistical analysis

The percentage of oocytes undergoing GVBD was calculated for each replicate and transformed (arcsine) before analysis. Results from GVBD, cAMP, number of oocytes ovulated, and quantitative PCR were analyzed by either Student's t test or two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's honestly significant difference post hoc test if a positive F test was detected. The JMP version 7.1 statistical analysis software (SAS, Cary, NC) and Microsoft Excel were used for analysis.

Results

Zinc is required for maintenance of meiotic arrest

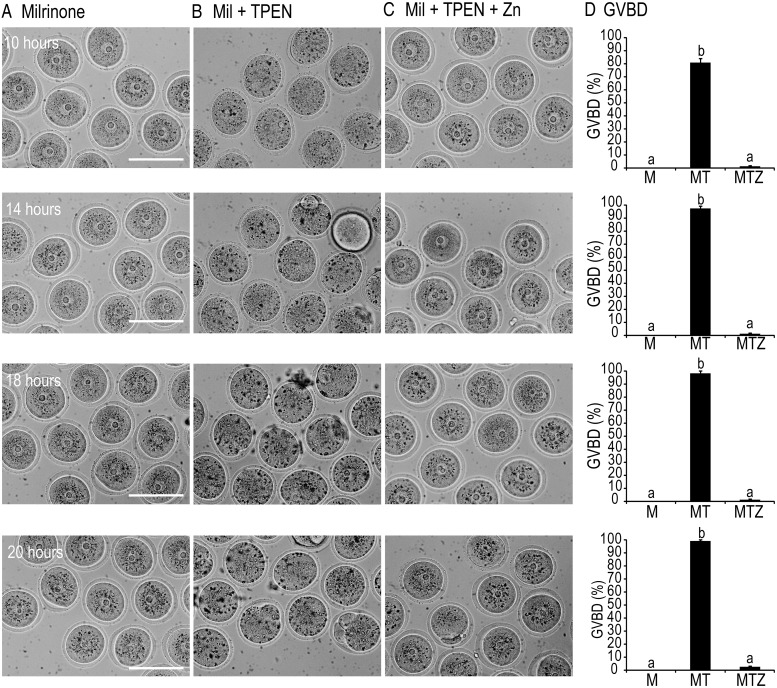

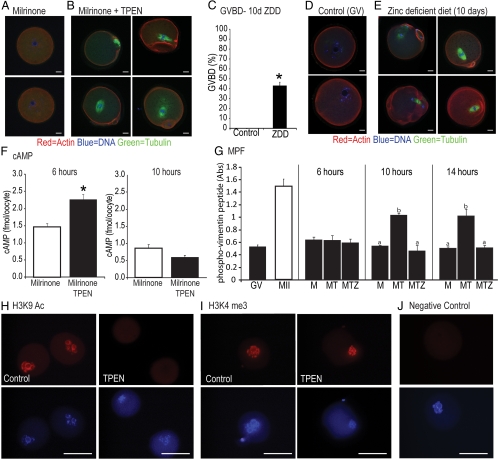

In experiments designed to test the effect of zinc on cumulus cell function (see below), we observed that TPEN induced GVBD even in the presence of a PDE3A inhibitor, milrinone. To test whether TPEN affects GVBD in denuded oocytes, we cultured oocytes with milrinone alone, milrinone and TPEN, or milrinone, TPEN, and zinc (10 μm) for 10–20 h (Fig. 1). Before 10 h, there was no difference in the rate of GVBD between control and TPEN oocytes (data not shown). None of the control oocytes underwent GVBD during the treatment period (n = 88) (Fig. 1, A and D). At 10 h, 80% of TPEN oocytes (n = 115) had undergone GVBD, and this increased to 91, 97, and 99% by 14, 16, and 20 h, respectively (Fig. 1, B and D, P < 0.05). Zinc supplementation restored meiotic arrest, and only 2% of oocytes (n = 85) had resumed meiosis by 20 h (Fig. 1, C and D). Even though TPEN caused resumption of meiosis, oocytes did not reach metaphase II as indicated by a lack of polar body extrusion (Fig. 1B). To further assess meiotic defects caused by TPEN, we analyzed spindle morphology by immunofluorescence staining with antitubulin (α and γ), phalloidin-TRITC, and DAPI to stain microtubules, actin filaments, and DNA, respectively. As shown in Fig. 2A, control oocytes were effectively maintained at the GV stage with the chromatin in a surrounded nucleolus configuration. However, TPEN-treated oocytes resumed meiosis as indicated by GVBD and chromosome condensation but were unable to complete the first meiotic division (Fig. 2B). To examine the effect of zinc deficiency in vivo, weaned mice were fed control or ZDD for 10 d. Animals were primed on d 8 with PMSG to stimulate follicular development. In animals on a ZDD, 42.5% of oocytes had undergone precocious GVBD in the absence of an ovulatory signal (Fig. 2C, P < 0.05), whereas oocytes from control mice had an intact GV (Fig. 2, C and D). Confocal immunofluorescence of oocytes from ZDD mice showed several types of abnormal spindle configurations, including arrest at metaphase I and late telophase (Fig. 2E).

Fig. 1.

A–C, Bright-field images of oocytes cultured for 10, 14, 18, and 20 h in medium containing 10 μm milrinone (A), milrinone (Mil) plus 10 μm TPEN (B), or milrinone (Mil), TPEN, and 10 μm zinc (Zn) (C). Scale bar, 100 μm. D, Proportion of oocytes undergoing GVBD in milrinone (M) alone, milrinone plus TPEN (MT), or milrinone, TPEN, and 10 μm zinc (MTZ). Values are mean ± sem. a–c, Significant difference by ANOVA and Tukey's post hoc test, P < 0.05; n = 4.

Fig. 2.

A, Spindle staining using tubulin antibodies to stain microtubules, phalloidin-TRITC to stain actin filaments, and DAPI to stain DNA in oocytes cultured in milrinone for 20 h (control). B, Spindle staining of oocytes cultured with milrinone and TPEN (10 μm) for 20 h. C, Proportion of oocytes undergoing GVBD (germinal vesicle breakdown) from mice fed a control diet or a ZDD (zinc deficient diet) for 10 d and primed with PMSG (but not hCG) on d 8. D, Spindle staining of oocytes from mice fed control diet. E, Spindle staining of oocytes from animals fed a ZDD for 10 d. F, Levels of cAMP in oocytes treated with milrinone or milrinone plus TPEN and cultured for 6 and 10 h. G, MPF activity in oocytes treated with milrinone (M), milrinone and TPEN (MT), or milrinone, TPEN and zinc (10 μm) (MTZ) for 6, 10, and14 h. MPF activity in GV and MII oocytes are provided as a reference. H, Immunostaining for H3K9Ac in control and TPEN-treated oocytes cultured for 20 h. I, Immunostaining for H3K4me3 in control and TPEN-treated oocytes cultured for 20 h. J, Negative control with secondary antibody only. Scale bars, 10 μm (A, B, D, and E) and 50 μm (H–J). Values are mean ± sem. a–c, Significant differences by ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test, P < 0.05; n = 3. *, Significant difference by Student's t test, P < 0.05; n = 3.

Effect of TPEN on cAMP concentration and MPF activation

To determine whether cAMP levels decrease in TPEN-treated oocytes, we measured cAMP in control and TPEN oocytes before (6 h) and during (10 h) GVBD. Surprisingly, TPEN caused a significant increase in cAMP in oocytes at 6 h (Fig. 2F, P < 0.05), whereas by 10 h, levels of cAMP did not differ between control and TPEN oocytes (Fig. 2F). TPEN-induced GVBD is caused by increased MPF activity by 10–14 h, an effect blocked by exogenous zinc (Fig. 2G, P < 0.05).

Zinc depletion causes changes in histone modifications

Changes in histone modifications are associated with oocyte maturation. Acetylation of various amino acid residues on histone H3, including lysine 9, is decreased during maturation (38). Consistent with the initiation of maturation, acetylation of H3K9 was completely abolished by TPEN (Fig. 2H), even in oocytes that retained the surrounded nucleolus chromatin configuration. Another histone modification, trimethylated H3K4, is stable during oocyte maturation (39) and was not altered by treatment with TPEN (Fig. 2I). At least 25 oocytes from three different animals were analyzed for histone modifications.

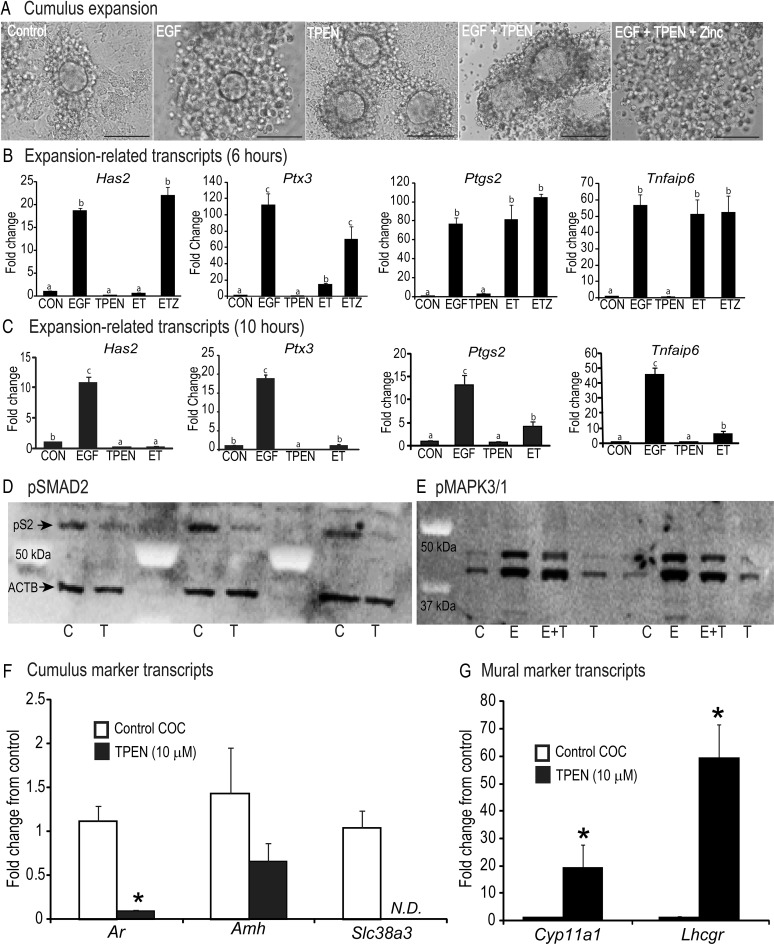

Effect of TPEN on cumulus expansion

To address whether the high intracellular zinc levels are required for cumulus expansion, intact COC were cultured as follows: control medium, EGF (10 ng/ml), TPEN (10 μm), EGF plus TPEN, or EGF plus TPEN and zinc (10 μm) for 15 h. Cumulus cells in the control group attached to the culture dish, whereas EGF treatment stimulated robust cumulus expansion (Fig. 3A). However, TPEN treatment alone prevented cumulus cells from attaching to the substrate and completely blocked EGF-induced cumulus expansion (Fig. 3A). Supplemental zinc restored EGF-induced cumulus expansion (Fig. 3A). The effect of TPEN on concentration of expansion-related transcripts differed at 6 and 10 h (Fig. 3, B and C). At 6 h, TPEN effectively inhibited EGF induction of Has2 and Ptx3 mRNA but not Ptgs2 or Tnfaip6 mRNA (Fig. 3B). Zinc supplementation restored both Has2 and Ptx3 mRNA but had no effect on Ptgs2 and Tnfaip6 mRNA (Fig. 3B). However, at 10 h, all four transcripts were effectively inhibited by TPEN, although Ptgs2 and Tnfaip6 mRNA were still higher than the control group (Fig. 3C). These time points were chosen based on previous determination of maximal induction of expansion transcripts during in vitro maturation (6, 37).

Fig. 3.

Panel A, Cumulus expansion in COC treated with medium only (CON), EGF (10 ng/ml), TPEN (10 μm), EGF plus TPEN (ET), or EGF, TPEN, and zinc (ETZ) (10 μm) for 15 h. Scale bar, 100 μm. Panel B, Levels of expansion-related transcripts Has2, Tnfaip6, Ptx3, and Ptgs2 in COC cultured as in panel A for 6 h. Panel C, Levels of expansion-related transcripts Has2, Tnfaip6, Ptx3, and Ptgs2 in COC cultured in control (CON), EGF, TPEN, and EGF plus TPEN for 10 h. D, Western blot for pSMAD2 (upper band) and actin (ACTB, lower band) in control (C) and TPEN-treated (T) COC for 6 h. E, Western blot for pMAPK3/1 in COC treated with medium only (C, control), EGF (E, 10 ng/ml), EGF plus TPEN (E+T), or TPEN (T, 10 μm) for 4 h. F, Levels of cumulus marker transcripts (Ar, Amh, and Slc38a3) in control and TPEN-treated COC cultured for 20 h. G, Levels of mural marker transcripts (Cyp11a1 and Lhcgr) in control and TPEN-treated COC cultured for 20 h. Values are mean ± sem. a–c, Significant differences by ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test, P < 0.05; n = 4. *, Significant difference by Student's t test, P < 0.05; n = 3–4.

Effect of TPEN on pSMAD2 and MAPK3/1 activation

To determine whether TPEN affects pSMAD2 activation, COC were incubated in medium alone (control) or with TPEN for 6 h. After culture, 35 COC per group were analyzed by Western blot. In control COC, pSMAD2 levels were high (Fig. 3D), but TPEN markedly reduced pSMAD2 levels after 6 h (Fig. 3D). To test the effects of TPEN on pMAPK3/1 activation, COC were treated with medium only, EGF (10 ng/ml), TPEN (10 μm), or both EGF and TPEN for 4 h. This time point was chosen based on robust pMAPK3/1 activation in previous reports (37). However, unlike for pSMAD2 activation, TPEN did not prevent EGF-induced pMAPK3/1 activation (Fig. 3E).

Effect of TPEN on cumulus and mural transcripts

Because TPEN inhibited pSMAD2 activation, we sought to determine whether cumulus and mural transcripts were altered by TPEN. In cumulus cells from COC treated with TPEN for 20 h, levels of Ar mRNA were much lower and levels of Slc38a3 were undetectable (Fig. 3F, P < 0.05). Amh mRNA decreased but was not significantly different after TPEN treatment (Fig. 3F). In contrast to the cumulus transcripts, TPEN alone dramatically increased mural transcripts, Cyp11a1 and Lhcgr mRNA, by 20- to 60-fold (Fig. 3G, P < 0.05).

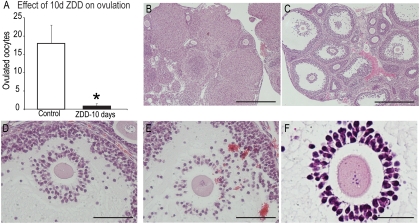

In vivo zinc deficiency impairs oocyte maturation, cumulus expansion, and ovulation

TPEN caused defects in oocyte maturation, cumulus expansion, and gene expression in vitro. To test whether zinc deficiency in vivo has similar effects, newly weaned mice were fed a control or ZDD for 3 or 10 d. Animals were fed the same amount of feed and body weight did not differ on d 3 (control, 18.47 ± 0.87 g; ZDD, 17.88 ± 1.00 g) but was slightly reduced on d 10 in the ZDD group (control, 21.72 ± 0.35 g; ZDD, 18.39 ± 1.10 g, P < 0.05), although this did not reduce growth of antral follicles in ZDD animals (Fig. 4C). To test ovulatory capacity, animals were induced to ovulate with PMSG (48 h) followed by hCG (13 h). Already mentioned was the dramatic increase in premature GVBD before an ovulatory signal in PMSG-primed animals on a ZDD for 10 d (Fig. 2C). In addition to promoting GVBD in oocytes, a ZDD for 10 d completely blocked ovulation as indicated by the near absence of oocytes in the oviduct of superovulated mice (1.0 ± 0.8 ZDD vs. 18.2 ± 4.1 oocytes per mouse, Fig. 4A). Histological examination of control ovaries revealed abundant CL (Fig. 4B). Dramatically, animals in the ZDD group had large unruptured follicles with no evidence of ovulation or CL formation (Fig. 4C). Moreover, COC within these follicles showed various degrees of expansion from fairly normal expansion to little or no expansion (Fig. 4, C–F), even though the oocytes had resumed meiosis (Figs. 4F and 2C). In animals receiving a ZDD for 3 d, there was no difference in ovulation rate between control and ZDD mice (Fig. 5A). The ovaries of control animals had normal CL formation indicating ovulation had occurred (Fig. 5B). However, examination of ovarian sections from ZDD animals revealed significantly more trapped oocytes in animals receiving ZDD compared with controls (5 ± 0.70 ZDD; 2 ± 0.63 control, P < 0.05)(Fig. 5, C–F). Moreover, although a ZDD for 3 d did not decrease the number of ovulated oocytes, only 77% of oocytes had reached metaphase II compared with 98% for controls (Fig. 5G, P < 0.05). Spindle morphology was normal in control oocytes (Fig. 5H). However, as with animals treated with a ZDD for 10 d and oocytes treated with TPEN in vitro, ovulated oocytes from animals treated for 3 d with a ZDD had various spindle defects including arrest at metaphase and late telophase of meiosis I (Fig. 5I).

Fig. 4.

A, Number of ovulated oocytes from mice fed a control diet or a ZDD for 10 d. Animals were primed with PMSG on d 8 and hCG on d 10, and ovulated COC were collected 13 h later. B, Hematoxylin- and eosin-stained sections from animals fed a control diet. Scale bar, 500 μm. C, Hematoxylin- and eosin-stained sections from animals fed a ZDD diet. Scale bar, 500 μm. D and E, Close-up of two large antral follicles from ZDD animals that failed to ovulate. Scale bar, 100 μm. F, Close-up of a COC from a ZDD animal that failed to undergo cumulus expansion, but the oocyte still matured as indicated by condensed chromosomes. Scale bar, 50 μm. Values are mean ± sem. *, Significant difference by Student's t test, P < 0.05; n = 5–6.

Fig. 5.

A, Number of ovulated oocytes from mice fed a control diet or a ZDD for 3 d and primed with PMSG on d 1 and hCG on d 3 and collected 13 h later. B, Hematoxylin- and eosin-stained sections from animals fed a control diet. Scale bar, 500 μm. C, Hematoxylin- and eosin-stained sections from animals fed a ZDD diet. Scale bar, 500 μm. D–F, Close-up of three large luteinizing follicles on the same ovary with trapped oocytes. Scale bar, 100 μm. G, Proportion of ovulated oocytes with a polar body from animals fed control or a ZDD for 3 d. H, Spindle staining of ovulated oocytes from control animals stained with antitubulin, phalloidin-TRITC, and DAPI to localize microtubules, actin filaments, and DNA, respectively. Scale bar, 50 μm. I, Spindle staining of ovulated oocytes from animals fed a ZDD showing examples of defective maturation in oocytes lacking a polar body (33% of total). Scale bar, 50 μm. Arrowheads indicate location of attached cumulus cells. Values are mean ± sem. *, Significant difference by Student's t test, P < 0.05; n = 4–6.

Discussion

Ovulation is regulated by several coordinated pathways to stimulate oocyte maturation, cumulus expansion, and follicle rupture. The main findings of this study are that zinc is intimately involved in controlling oocyte maturation and granulosa cell function before and during ovulation. Zinc deficiency blocks cumulus cell differentiation, cumulus expansion, and follicle rupture. One important pathway disrupted by zinc deficiency in granulosa cells is activation of pSMAD2/3. In GV-stage oocytes, zinc deficiency causes premature resumption of meiosis, but once GVBD occurs, zinc deficiency prevents completion of maturation and oocytes fail to reach MII. The dramatic effect of acute zinc deficiency in vivo and in vitro on both oocyte and somatic cell function has implications for the treatments and management of human infertility and contraception. In particular, the modulation of zinc availability during ovulation and in vitro maturation could be used to improve oocyte fertility during assisted reproduction or potentially as a contraceptive agent to prevent ovulation.

Zinc is required to maintain meiotic arrest before ovulation

Total zinc content increases 30–50% in oocytes during in vitro maturation (33). Nevertheless, even with lower levels of zinc in GV oocytes, we clearly demonstrate a previously unknown role for zinc in maintaining meiotic arrest before ovulation. In antral follicles, the oocyte remains in prophase I of meiosis due to the activity of several reinforcing mechanisms to maintain high cAMP/PKA in the oocyte, which then prevents the activation of MPF (CDK1/cyclin B1). In vitro, oocytes will spontaneously mature unless cultured with a PDE3A inhibitor, such as milrinone. Surprisingly, TPEN caused GVBD in virtually all oocytes even in the presence of milrinone. Exogenous zinc prevented GVBD, indicating the effect of TPEN was zinc specific. However, TPEN-induced maturation does not occur until approximately 10 h. This is much later than spontaneous maturation of denuded oocytes where 99% have undergone GVBD by 2 h (40). Nevertheless, TPEN induced GVBD in more than 90% of oocytes, signifying that it activates a robust mechanism. These results show that a zinc-dependent process is required to maintain meiotic arrest. Interestingly, zinc is also required to maintain MII arrest (41), but the mechanism controlling arrest in GV oocytes likely differs from MII eggs because MPF activity is low in GV oocytes but high in MII eggs. One zinc target protein mediating MII arrest is early meiosis inhibitor 2 (EMI2), which blocks cyclin B1 ubiquination and degradation by inhibiting the anaphase-promoting complex (42, 43). EMI2 contains a zinc-binding region that is essential for blocking anaphase-promoting complex activity during MII arrest (41, 43, 44). In frogs and mice, mutation of the EMI2 zinc-binding region completely abolishes cytostatic activity (44, 45), demonstrating that this zinc binding motif is essential for maintaining MII arrest.

Fully grown oocytes are transcriptionally silent (46–48). Therefore, in order for GVBD to occur, TPEN must alter the activity of one or more intracellular proteins to activate MPF. The increase in MPF activity by 10 h indicates that TPEN treatment induced a true meiotic event and not simply nonspecific degradation of the GV. Interestingly, TPEN does not seem to activate MPF by decreasing cAMP. In fact, TPEN actually increased cAMP at 6 h. At 10 h, cAMP was not different from control oocytes, even though GVBD was in full swing. This was completely unexpected because GVBD does not normally occur in the presence of high cAMP. One possibility is that TPEN treatment causes increased production of the cAMP metabolite, 5′-AMP, which will then activate the kinase, AMPK (AMP kinase). As with TPEN, chemical activators of AMPK can overcome meiotic arrest maintained by milrinone with similar kinetics as TPEN (49). Moreover, the relative decrease in cAMP from 6–10 h in TPEN-treated oocytes could generate enough 5′-AMP to activate AMPK and promote GVBD as shown previously (50). This concept is supported in cancer cells where zinc deficiency increases cAMP (51). There are two ways that TPEN or zinc deficiency could increase cAMP in oocytes. One way is by further suppressing PDE3A activity, which is normally stimulated by zinc (52, 53), and the second is by stimulating adenylate cyclase activity, which is normally suppressed by zinc (54). How zinc deficiency increases cAMP in oocytes and whether this transient increase is responsible for GVBD remains unknown, but clearly zinc is a major player in preventing meiotic resumption in oocytes.

Although GVBD occurs in TPEN-treated oocytes, meiosis does not proceed normally. Similar to previous findings (33), TPEN caused severe spindle defects and failure to properly segregate homologous chromosomes. Most oocytes either arrest at MI or progress to late telophase before meiotic progression is halted. However, unlike findings by Kim and colleagues (33), we did not observe symmetrical cell division in oocytes treated with TPEN and milrinone. Other changes associated with maturation also occur in TPEN-treated oocytes. For example, histone acetylation normally decreases dramatically, whereas methylation is not affected in mature oocytes compared with GV-stage oocytes (38, 39). Our results show that TPEN treatment completely abolishes histone H3K9 acetylation but had no effect on histone H3K4 trimethylation. These changes further emphasize that zinc is involved in regulation of chromatin modification, but whether this is a direct effect on chromatin modifying proteins or an indirect result of precocious maturation is unclear.

The essential role of zinc in preventing premature GVBD was also demonstrated in vivo by feeding mice a ZDD for 10 d. This relatively acute period of zinc deficiency caused 42.5% of oocytes to undergo GVBD in the absence of an ovulatory stimulus. This is a rather dramatic effect of short-term zinc deficiency and shows how sensitive the ovary is to conditions where zinc is limiting. Perhaps zinc transport into the oocyte is not very efficient, and any decrease in follicular zinc would quickly cause zinc deficiency in the oocyte. Spindle defects in oocytes from ZDD mice were identical to TPEN-treated oocytes, confirming that zinc is an essential factor for maintaining meiotic arrest and for completion of meiosis I in vivo. An even shorter 3-d ZDD treatment did not cause premature GVBD (data not shown) but did result in failure to complete meiosis I as indicated by the absence of a polar body in 23% of ovulated eggs. As in TPEN-treated oocytes, spindle defects after 3 d on a ZDD are consistent with a failure to complete meiosis I. Thus, even a very acute exposure to a ZDD (3–10 d) results in significant meiotic defects. This could be an underappreciated source of reproductive dysfunction in individuals receiving an otherwise adequate zinc diet or individuals suffering marginal, but prolonged zinc deficiency caused by alcohol-induced liver damage (55, 56).

Cumulus cell function is dependent on zinc

Cumulus expansion is an essential ovulatory process (57) that requires activation of MAPK3/1 by EGF-LP and of pSMAD2/3 by oocyte-secreted factors that together stimulate the expansion-related transcripts Has2, Ptgs2, Ptx3, and Tnfaip6 mRNA (6, 12, 37, 58–60). Significantly, TPEN completely blocked cumulus expansion, an effect rescued by exogenous zinc. TPEN did not prevent EGF from inducing MAPK3/1 activation, but it remains to be determined whether TPEN diminishes MAPK3/1 activation. However, TPEN blocked EGF induction of Has2 and Ptx3 but not Ptgs2 or Tnfaip6 mRNA at 6 h. In contrast, all four transcripts were inhibited at 10 h. This pattern is identical to that observed using a pSMAD2/3-specific inhibitor, SB431542 (6). Indeed, TPEN completely suppressed pSMAD2 by 6 h. This effect alone is sufficient to block cumulus expansion (6), but effects on other proteins cannot be ruled out. One possible mechanism to explain how TPEN decreases pSMAD2 levels is that zinc is required as a cofactor for pSMAD2/3 complexes to bind DNA (61, 62). Insufficient zinc could cause pSMAD2/3 protein complexes to dissociate from the chromatin and be targeted for degradation. The zinc transporter SLC39A13 controls bone morphogenetic protein or TGF-β signaling by regulating the availability of zinc to bind SMAD proteins in connective tissues (63), providing further support for a zinc-SMAD interaction. Other possibilities are that zinc deficiency could directly increase pSMAD2/3 protein degradation, decrease the kinase activity of the type 1 receptors that phosphorylate SMAD, or potentially activate phosphatase enzymes that dephosphorylate pSMAD in cumulus cells. Nevertheless, the novel observation that zinc-dependent mechanisms regulate SMAD signaling in the follicle represents a clear advance in our understanding of the regulation of this important pathway for ovarian development. These results also suggest that zinc may be important for the action of other important regulatory factors that signal through SMAD-mediated pathways. Many of these factors such as growth and differentiation factor 9, activin, TGF-β, and bone morphogenetic protein act throughout follicular development. Whether perturbations in zinc metabolism affect development of preantral follicles is an intriguing and open question.

A second main finding in regard to cumulus cell function is that zinc plays a crucial role in determining the levels of cumulus vs. mural cell transcripts. Cumulus cell differentiation is driven by secreted factors emanating from the centrally located oocyte, whereas the mural cell lineage develops under the influence of gonadotropins, particularly FSH (6, 64). A hallmark of these two cell lineages is that they express different subsets of transcripts. Cumulus cells express Amh, Ar, and Slc38a3 mRNA at much higher levels, whereas mural granulosa cells express higher levels of Lhcgr and Cyp11a1 mRNA (6, 11). Oocyte secreted factors acting through pSMAD2/3 signaling pathways promote cumulus transcript levels and inhibit mural transcripts (6, 14, 60). Consistent with a reduction in pSMAD2/3 activation in cumulus cells, TPEN caused a decrease in cumulus cell transcripts and, surprisingly, caused a robust increase in mural transcripts. These observations show that TPEN treatment has transcript-specific effects and does not necessarily cause global changes in the cumulus cell transcriptome. Furthermore, zinc deficiency alters the differentiation pathway of cumulus and perhaps mural granulosa cells by altering the potency of SMAD2/3 signaling pathways. The large increase in Lhcgr and Cyp11a1 mRNA, as well as Star mRNA (data not shown), in cumulus cells also suggests that zinc may have a role during luteinization, but this remains to be determined. Both the robust suppression of expansion-related transcripts and the decrease in cumulus cell transcript levels demonstrate the wide-ranging consequences of zinc insufficiency in cumulus cells. In future work, it will be particularly interesting to determine whether zinc-dependent processes affect progesterone production and CL development. It will take some time to identify the totality of zinc effectors in cumulus cells and oocytes, but SMAD2/3 proteins are an important target identified in this study.

In vivo zinc deficiency causes ovulatory defects

Zinc deficiency is common in many parts of the world (65) and in certain populations in the United States (66). Dietary zinc deficiency is known to cause developmental problems throughout pregnancy (28, 29). This is not surprising because zinc is a cofactor for many proteins, including transcription factors and enzymes, important for a variety of cellular and developmental processes (67–69). Zinc can also impact the developmental potential of oocytes. Dietary zinc deficiency in rats for 3 d centered on ovulation and fertilization results in lower-quality blastocyst embryos (70, 71). In our studies, animals received a ZDD for 3 d ending just before (PMSG) or after (PMSG plus hCG) ovulation. Our results show that acute zinc deficiency causes meiotic defects in ovulated oocytes. Whether developmental potential of these oocytes is altered is an important question that is currently under investigation. In addition to their meiotic defects, oocytes from ZDD animals become trapped in luteinizing follicles at a higher rate, suggesting that cumulus expansion is defective. A longer 10-d ZDD treatment caused a more severe phenotype. Cumulus expansion was limited in many cases, and follicle rupture did not occur. Nevertheless, oocytes resumed meiosis, albeit prematurely, and with severe spindle defects. The less robust suppression of cumulus expansion caused by zinc deficiency in vivo compared with TPEN in vitro is probably due to a milder zinc deficiency caused a ZDD compared with the highly permeable TPEN. Importantly, in our studies, animals received exogenous gonadotropins to stimulate follicular development. Therefore, any defects observed are not due to lack of gonadotropin stimulation or insufficient follicular development. The lack of follicle rupture in the ZDD group is likely due to inhibition of matrix metalloproteases and/or members of a disintegrin-like and metalloprotease thrombospondin type 1 motif (ADAMTS) family of peptidases, both of which require zinc as a cofactor (72, 73). In primate preovulatory follicles, injection of a matrix metalloprotease inhibitor (GM6001) blocks follicle rupture with a phenotype similar to our ZDD animals (74).

A model of zinc action during the periovulatory period is shown in Fig. 6. We have uncovered dramatic effects of zinc in preventing premature GVBD. In cumulus cells, we described an important role for zinc in cumulus expansion and pSMAD2/3 signaling and in follicles showed that acute zinc deficiency blocks follicle rupture during ovulation. Knowledge of zinc metabolism and action in the oocyte, cumulus cells, and early embryo could lead to improved in vitro maturation procedures for human in vitro fertilization, which are very inefficient (4–27% clinical pregnancy/transfer) (75–77). In cattle, zinc supplementation of in vitro maturation medium improves blastocyst production from 17 to 30% (78). Also, large influx and efflux of zinc ions during fertilization and in early zygotes suggests a role for zinc as a signaling molecule during early development (79). Thus, our current findings firmly establish zinc as an essential factor for full fertility.

Fig. 6.

Model showing proposed action of zinc-dependent mechanisms in oocytes and cumulus cells before and during ovulation. Before ovulation, the combined effects of natriuretic peptide precursor C (NPPC) and GPR3 and GPR12 maintain high cAMP to prevent MPF activation. NPPC binds to the natriuretic peptide receptor 2 (NPR2) receptor and generates cGMP, which passes through gap junctions into the oocyte and inhibits PDE3A. GPR3 and GPR12 activate adenylate cyclase (AC) to generate cAMP in the oocyte. Zinc enters the oocyte and cumulus cells through specific transporters. In oocytes, zinc may negatively regulate cAMP levels by inhibiting adenylate cyclase and stimulating PDE activity. Additionally, zinc is involved in preventing meiotic resumption by regulating MPF or downstream processes to prevent premature GVBD. In cumulus cells, zinc is required to enable pSMAD2/3 signaling to maintain the cumulus phenotype. After the LH surge, EGF-LP in conjunction with zinc-enabled pSMAD2/3 signaling promotes cumulus expansion. In oocytes, a zinc-mediated process is required for completion of meiosis I.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. John Eppig and Alan Johnson for helpful comments and Dr. Shannon Kelleher for insightful discussions on the biology of zinc.

This research was supported by start-up funds from the College of Agricultural Sciences at The Pennsylvania State University and National Institutes of Health Grant HD057283 to F.J.D.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- AMPK

- AMP kinase

- CDK1

- cyclin-dependent kinase 1

- CL

- corpus luteum

- DAPI

- 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- EGF

- epidermal growth factor

- EGF-LP

- EGF-like peptides

- EMI2

- early meiosis inhibitor 2

- GPR

- G protein-coupled receptor

- GVBD

- germinal vesicle breakdown

- hCG

- human chorionic gonadotropin

- MII

- metaphase II

- MPF

- maturation-promoting factor

- PBST

- PBS with Tween 20

- PDE3A

- phosphodiesterase 3A

- PKA

- protein kinase A

- PMSG

- pregnant mare serum gonadotropin

- pSMAD

- phospho-Sma- and Mad-related protein

- TPEN

- N,N,N′,N′-tetrakis (2-pyridylmethyl) ethylenediamine

- TRITC

- tetraethylrhodamine isothiocyanate

- ZDD

- zinc-deficient diet.

References

- 1. Zhang M, Su YQ, Sugiura K, Xia G, Eppig JJ. 2010. Granulosa cell ligand NPPC and its receptor NPR2 maintain meiotic arrest in mouse oocytes. Science 330:366–369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vaccari S, Weeks JL, 2nd, Hsieh M, Menniti FS, Conti M. 2009. Cyclic GMP signaling is involved in the luteinizing hormone-dependent meiotic maturation of mouse oocytes. Biol Reprod 81:595–604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Norris RP, Ratzan WJ, Freudzon M, Mehlmann LM, Krall J, Movsesian MA, Wang H, Ke H, Nikolaev VO, Jaffe LA. 2009. Cyclic GMP from the surrounding somatic cells regulates cyclic AMP and meiosis in the mouse oocyte. Development 136:1869–1878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mehlmann LM, Saeki Y, Tanaka S, Brennan TJ, Evsikov AV, Pendola FL, Knowles BB, Eppig JJ, Jaffe LA. 2004. The Gs-linked receptor GPR3 maintains meiotic arrest in mammalian oocytes. Science 306:1947–1950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hinckley M, Vaccari S, Horner K, Chen R, Conti M. 2005. The G-protein-coupled receptors GPR3 and GPR12 are involved in cAMP signaling and maintenance of meiotic arrest in rodent oocytes. Dev Biol 287:249–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Diaz FJ, Wigglesworth K, Eppig JJ. 2007. Oocytes determine cumulus cell lineage in mouse ovarian follicles. J Cell Sci 120:1330–1340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Eppig JJ, Pendola FL, Wigglesworth K. 1998. Mouse oocytes suppress cAMP-induced expression of LH receptor messenger RNA by granulosa cells in vitro. Mol Reprod Dev 49:327–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sugiura K, Su YQ, Diaz FJ, Pangas SA, Sharma S, Wigglesworth K, O'Brien MJ, Matzuk MM, Shimasaki S, Eppig JJ. 2007. Oocyte-derived BMP15 and FGFs cooperate to promote glycolysis in companion cumulus cells. Development 134:2593–2603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sugiura K, Pendola FL, Eppig JJ. 2005. Oocyte control of metabolic cooperativity between oocytes and companion granulosa cells: energy metabolism. Dev Biol 279:20–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Su YQ, Sugiura K, Wigglesworth K, O'Brien MJ, Affourtit JP, Pangas SA, Matzuk MM, Eppig JJ. 2008. Oocyte regulation of metabolic cooperativity between mouse cumulus cells and oocytes: BMP15 and GDF9 control cholesterol biosynthesis in cumulus cells. Development 135:111–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Eppig JJ, Pendola FL, Wigglesworth K, Pendola JK. 2005. Mouse oocytes regulate metabolic cooperativity between granulosa cells and oocytes: amino acid transport. Biol Reprod 73:351–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vanderhyden BC, Caron PJ, Buccione R, Eppig JJ. 1990. Developmental pattern of the secretion of cumulus-expansion enabling factor by mouse oocytes and the role of oocytes in promoting granulosa cell differentiation. Dev Biol 140:307–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dragovic RA, Ritter LJ, Schulz SJ, Amato F, Armstrong DT, Gilchrist RB. 2005. Role of oocyte-secreted growth differentiation factor 9 in the regulation of mouse cumulus expansion. Endocrinology 146:2798–2806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Su YQ, Sugiura K, Li Q, Wigglesworth K, Matzuk MM, Eppig JJ. 2010. Mouse Oocytes enable LH-induced maturation of the cumulus-oocyte complex via promoting EGF receptor-dependent signaling. Mol Endocrinol 24:1230–1239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Park JY, Su YQ, Ariga M, Law E, Jin SL, Conti M. 2004. EGF-like growth factors as mediators of LH action in the ovulatory follicle. Science 303:682–684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hsieh M, Lee D, Panigone S, Horner K, Chen R, Theologis A, Lee DC, Threadgill DW, Conti M. 2007. Luteinizing hormone-dependent activation of the epidermal growth factor network is essential for ovulation. Mol Cell Biol 27:1914–1924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Su YQ, Nyegaard M, Overgaard MT, Qiao J, Giudice LC. 2006. Participation of mitogen-activated protein kinase in luteinizing hormone-induced differential regulation of steroidogenesis and steroidogenic gene expression in mural and cumulus granulosa cells of mouse preovulatory follicles. Biol Reprod 75:859–867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Panigone S, Hsieh M, Fu M, Persani L, Conti M. 2008. Luteinizing hormone signaling in preovulatory follicles involves early activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor pathway. Mol Endocrinol 22:924–936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Han SJ, Chen R, Paronetto MP, Conti M. 2005. Wee1B is an oocyte-specific kinase involved in the control of meiotic arrest in the mouse. Curr Biol 15:1670–1676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Masciarelli S, Horner K, Liu C, Park SH, Hinckley M, Hockman S, Nedachi T, Jin C, Conti M, Manganiello V. 2004. Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase 3A-deficient mice as a model of female infertility. J Clin Invest 114:196–205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ochsner SA, Russell DL, Day AJ, Breyer RM, Richards JS. 2003. Decreased expression of tumor necrosis factor-α-stimulated gene 6 in cumulus cells of the cyclooxygenase-2 and EP2 null mice. Endocrinology 144:1008–1019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Diaz FJ, Wigglesworth K, Eppig JJ. 2007. Oocytes are required for the preantral granulosa cell to cumulus cell transition in mice. Dev Biol 305:300–311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Varani S, Elvin JA, Yan C, DeMayo J, DeMayo FJ, Horton HF, Byrne MC, Matzuk MM. 2002. Knockout of pentraxin 3, a downstream target of growth differentiation factor-9, causes female subfertility. Mol Endocrinol 16:1154–1167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ochsner SA, Day AJ, Rugg MS, Breyer RM, Gomer RH, Richards JS. 2003. Disrupted function of tumor necrosis factor-α-stimulated gene 6 blocks cumulus cell-oocyte complex expansion. Endocrinology 144:4376–4384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sørensen MB, Stoltenberg M, Danscher G, Ernst E. 1999. Chelation of intracellular zinc ions affects human sperm cell motility. Mol Hum Reprod 5:338–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fuse H, Kazama T, Ohta S, Fujiuchi Y. 1999. Relationship between zinc concentrations in seminal plasma and various sperm parameters. Int Urol Nephrol 31:401–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Croxford TP, McCormick NH, Kelleher SL. 2011. Moderate zinc deficiency reduces testicular Zip6 and Zip10 abundance and impairs spermatogenesis in mice. J Nutr 141:359–365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Keen CL, Clegg MS, Hanna LA, Lanoue L, Rogers JM, Daston GP, Oteiza P, Uriu-Adams JY. 2003. The plausibility of micronutrient deficiencies being a significant contributing factor to the occurrence of pregnancy complications. J Nutr 133:1597S–1605S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Uriu-Adams JY, Keen CL. 2010. Zinc and reproduction: effects of zinc deficiency on prenatal and early postnatal development. Birth Defects Res B Dev Reprod Toxicol 89:313–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Apgar J. 1985. Zinc and reproduction. Annu Rev Nutr 5:43–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shaw NA, Dickey HC, Brugman HH, Blamberg DL, Witter JF. 1974. Zinc deficiency in female rabbits. Lab Anim 8:1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bernhardt ML, Kim AM, O'Halloran TV, Woodruff TK. 2011. Zinc requirement during meiosis I-meiosis II transition in mouse oocytes is independent of the MOS-MAPK pathway. Biol Reprod 84:526–536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kim AM, Vogt S, O'Halloran TV, Woodruff TK. 2010. Zinc availability regulates exit from meiosis in maturing mammalian oocytes. Nat Chem Biol 6:674–681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Favier AE. 1992. The role of zinc in reproduction. Hormonal mechanisms. Biol Trace Elem Res 32:363–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ito J, Shimada M, Terada T. 2003. Effect of protein kinase C activator on mitogen-activated protein kinase and p34(cdc2) kinase activity during parthenogenetic activation of porcine oocytes by calcium ionophore. Biol Reprod 69:1675–1682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 25:402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Diaz FJ, O'Brien MJ, Wigglesworth K, Eppig JJ. 2006. The preantral granulosa cell to cumulus cell transition in the mouse ovary: development of competence to undergo expansion. Dev Biol 299:91–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Akiyama T, Kim JM, Nagata M, Aoki F. 2004. Regulation of histone acetylation during meiotic maturation in mouse oocytes. Mol Reprod Dev 69:222–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sarmento OF, Digilio LC, Wang Y, Perlin J, Herr JC, Allis CD, Coonrod SA. 2004. Dynamic alterations of specific histone modifications during early murine development. J Cell Sci 117:4449–4459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Eppig JJ, Freter RR, Ward-Bailey PF, Schultz RM. 1983. Inhibition of oocyte maturation in the mouse: participation of cAMP, steroid hormones, and a putative maturation-inhibitory factor. Dev Biol 100:39–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Suzuki T, Yoshida N, Suzuki E, Okuda E, Perry ACF. 2010. Full-term mouse development by abolishing Zn2+-dependent metaphase II arrest without Ca2+ release. Development 137:2659–2669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Madgwick S, Hansen DV, Levasseur M, Jackson PK, Jones KT. 2006. Mouse Emi2 is required to enter meiosis II by reestablishing cyclin B1 during interkinesis. J Cell Biol 174:791–801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Shoji S, Yoshida N, Amanai M, Ohgishi M, Fukui T, Fujimoto S, Nakano Y, Kajikawa E, Perry ACF. 2006. Mammalian Emi2 mediates cytostatic arrest and transduces the signal for meiotic exit via Cdc20. EMBO J 25:834–845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Suzuki T, Suzuki E, Yoshida N, Kubo A, Li H, Okuda E, Amanai M, Perry ACF. 2010. Mouse Emi2 as a distinctive regulatory hub in second meiotic metaphase. Development 137:3281–3291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Schmidt A, Duncan PI, Rauh NR, Sauer G, Fry AM, Nigg EA, Mayer TU. 2005. Xenopus polo-like kinase Plx1 regulates XErp1, a novel inhibitor of APC/C activity. Genes Dev 19:502–513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Abe K, Inoue A, Suzuki MG, Aoki F. 2010. Global gene silencing is caused by the dissociation of RNA polymerase II from DNA in mouse oocytes. J Reprod Dev 56:502–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. De La Fuente R, Eppig JJ. 2001. Transcriptional activity of the mouse oocyte genome: companion granulosa cells modulate transcription and chromatin remodeling. Dev Biol 229:224–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Aoki F, Worrad DM, Schultz RM. 1997. Regulation of transcriptional activity during the first and second cell cycles in the preimplantation mouse embryo. Dev Biol 181:296–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Downs SM, Hudson ER, Hardie DG. 2002. A potential role for AMP-activated protein kinase in meiotic induction in mouse oocytes. Dev Biol 245:200–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Chen J, Chi MM, Moley KH, Downs SM. 2009. cAMP pulsing of denuded mouse oocytes increases meiotic resumption via activation of AMP-activated protein kinase. Reproduction 138:759–770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Skeef NS, Duncan JR. 1988. A possible relation between dietary zinc and cAMP in the regulation of tumour cell proliferation in the rat. Br J Nutr 59:437–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Percival MD, Yeh B, Falgueyret JP. 1997. Zinc dependent activation of cAMP-specific phosphodiesterase (PDE4A). Biochem Biophys Res Commun 241:175–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Law JS, McBride SA, Graham S, Nelson NR, Slotnick BM, Henkin RI. 1988. Zinc deficiency decreases the activity of calmodulin regulated cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases in vivo in selected rat tissues. Biol Trace Elem Res 16:221–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Klein C, Sunahara RK, Hudson TY, Heyduk T, Howlett AC. 2002. Zinc inhibition of cAMP signaling. J Biol Chem 277:11859–11865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Flynn A, Martier S, Sokol R, Miller S, Golden N, Del Villano B. 1981. Zinc status of pregnant alcoholic women: a determinant of fetal outcome. Lancet 317:572–575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sullivan JF, Lankford HG. 1965. Zinc metabolism and chronic alcoholism. Am J Clin Nutr 17:57–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Chen L, Russell PT, Larsen WJ. 1993. Functional significance of cumulus expansion in the mouse: roles for the preovulatory synthesis of hyaluronic acid within the cumulus mass. Mol Reprod Dev 34:87–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Su YQ, Denegre JM, Wigglesworth K, Pendola FL, O'Brien MJ, Eppig JJ. 2003. Oocyte-dependent activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (ERK1/2) in cumulus cells is required for the maturation of the mouse oocyte-cumulus complex. Dev Biol 263:126–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Shimada M, Hernandez-Gonzalez I, Gonzalez-Robayna I, Richards JS. 2006. Paracrine and autocrine regulation of EGF-like factors in cumulus oocyte complexes (COC) and granulosa cells: key roles for prostanglandin synthase 2 (Ptgs2) and progesterone receptor (Pgr). Mol Endocrinol 20:1352–1365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Dragovic RA, Ritter LJ, Schulz SJ, Amato F, Thompson JG, Armstrong DT, Gilchrist RB. 2007. Oocyte-secreted factor activation of SMAD 2/3 signaling enables initiation of mouse cumulus cell expansion. Biol Reprod 76:848–857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Chai J, Wu JW, Yan N, Massagué J, Pavletich NP, Shi Y. 2003. Features of a Smad3 MH1-DNA Complex. J Biol Chem 278:20327–20331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. BabuRajendran N, Palasingam P, Narasimhan K, Sun W, Prabhakar S, Jauch R, Kolatkar PR. 2010. Structure of Smad1 MH1/DNA complex reveals distinctive rearrangements of BMP and TGF-β effectors. Nucleic Acids Res 38:3477–3488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Fukada T, Civic N, Furuichi T, Shimoda S, Mishima K, Higashiyama H, Idaira Y, Asada Y, Kitamura H, Yamasaki S, Hojyo S, Nakayama M, Ohara O, Koseki H, Dos Santos HG, Bonafe L, Ha-Vinh R, Zankl A, Unger S, Kraenzlin ME, Beckmann JS, Saito I, Rivolta C, Ikegawa S, Superti-Furga A, Hirano T. 2008. The zinc transporter SLC39A13/ZIP13 is required for connective tissue development: its involvement in BMP/TGF-β signaling pathways. PLoS One 3:e3642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Eppig JJ, Wigglesworth K, Pendola F, Hirao Y. 1997. Murine oocytes suppress expression of luteinizing hormone receptor messenger ribonucleic acid by granulosa cells. Biol Reprod 56:976–984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Wuehler SE, Peerson JM, Brown KH. 2005. Use of national food balance data to estimate the adequacy of zinc in national food supplies: methodology and regional estimates. Public Health Nutr 8:812–819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Schneider JM, Fujii ML, Lamp CL, Lönnerdal B, Zidenberg-Cherr S. 2007. The prevalence of low serum zinc and copper levels and dietary habits associated with serum zinc and copper in 12- to 36-month-old children from low-income families at risk for iron deficiency. J Am Diet Assoc 107:1924–1929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Berg JM, Shi Y. 1996. The galvanization of biology: a growing appreciation for the roles of zinc. Science 271:1081–1085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Vallee BL, Auld DS. 1990. Zinc coordination, function, and structure of zinc enzymes and other proteins. Biochemistry 29:5647–5659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Ravasi T, Huber T, Zavolan M, Forrest A, Gaasterland T, Grimmond S, Hume DA; RIKEN GER Group; GSL Members 2003. Systematic characterization of the zinc-finger-containing proteins in the mouse transcriptome. Genome Res 13:1430–1442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Hurley LS, Shrader RE. 1975. Abnormal development of preimplantation rat eggs after three days of maternal dietary zinc deficiency. Nature 254:427–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Peters JM, Wiley LM, Zidenberg-Cherr S, Keen CL. 1991. Influence of short-term maternal zinc deficiency on the in vitro development of preimplantation mouse embryos. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 198:561–568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Apte SS. 2009. A disintegrin-like and metalloprotease (reprolysin-type) with thrombospondin type 1 motif (ADAMTS) superfamily: functions and mechanisms. J Biol Chem 284:31493–31497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Tallant C, Marrero A, Gomis-Rüth FX. 2010. Matrix metalloproteinases: fold and function of their catalytic domains. Biochim Biophys Acta 1803:20–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Peluffo MC, Murphy MJ, Baughman ST, Stouffer RL, Hennebold JD. 2011. Systematic analysis of protease gene expression in the rhesus macaque ovulatory follicle: metalloproteinase involvement in follicle rupture. Endocrinology 152:3963–3974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Trounson A, Wood C, Kausche A. 1994. In vitro maturation and the fertilization and developmental competence of oocytes recovered from untreated polycystic ovarian patients. Fertil Steril 62:353–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Cha KY, Koo JJ, Ko JJ, Choi DH, Han SY, Yoon TK. 1991. Pregnancy after in vitro fertilization of human follicular oocytes collected from nonstimulated cycles, their culture in vitro and their transfer in a donor oocyte program. Fertil Steril 55:109–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Child TJ, Abdul-Jalil AK, Gulekli B, Tan SL. 2001. In vitro maturation and fertilization of oocytes from unstimulated normal ovaries, polycystic ovaries, and women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril 76:936–942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Picco SJ, Anchordoquy JM, de Matos DG, Anchordoquy JP, Seoane A, Mattioli GA, Errecalde AL, Furnus CC. 2010. Effect of increasing zinc sulphate concentration during in vitro maturation of bovine oocytes. Theriogenology 74:1141–1148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Kim AM, Bernhardt ML, Kong BY, Ahn RW, Vogt S, Woodruff TK, O'Halloran TV. 2011. Zinc sparks are triggered by fertilization and facilitate cell cycle resumption in mammalian eggs. ACS Chem Biol 6:716–723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]