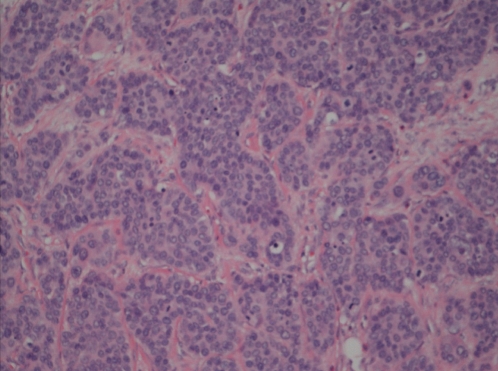

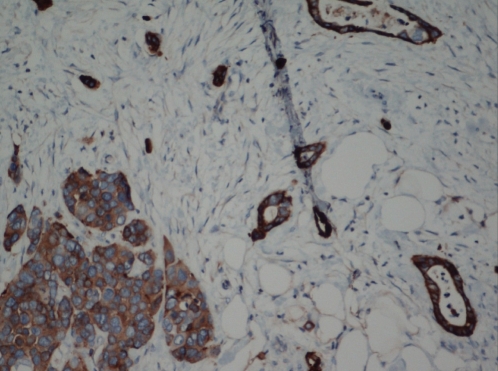

A 58-year-old man was referred in June 1991 with rectal bleeding for a colonoscopy that showed a sigmoid adenocarcinoma. Anterior resection revealed extension into, but not through, the muscularis propria, as well as 18 benign lymph nodes. Annual colonscopies were performed for five years, then every three years. In 2002, he underwent prostatectomy for prostate carcinoma. In 2008, a stage IVA, diffuse large B-cell right testicular lymphoma was treated with right orchidectomy, scrotal radiation and six cycles of CHOP-R (cyclophosphamide-doxorubicin-vincristine-prednisolone-rituximab). In 2008, colonoscopy and computed tomography (CT) scans of the head, abdomen and pelvis were normal, with no evidence of lymphoma. While travelling in southern France and Spain in June 2011, he developed abdominal pain and diarrhea for three days. This resolved for approximately one week and then recurred over a two-week period after his return to Canada. His physical examination was normal and laboratory studies revealed a mild anemia (hemoglobin level 122 g/L), but a normal white blood cell count and no left shift or eosinophilia. Fecal studies for bacteria and parasites were negative. A CT scan showed circumferential thickening of the hepatic flexure along with hepatic hypodense lesions, and colonoscopy showed an obstructing carcinoma. A right hemicolectomy and partial hepatectomy revealed a large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma invading through the colonic wall and involving seven of 14 regional lymph nodes and the liver. Microscopic evaluation showed predominately trebecular and insular architecture; the nests comprised of relatively monomorphous, but large cells, with moderate amounts of cytoplasm, an open nuclear chromatin pattern and a high mitotic apoptotic rate (Figure 1). Immunohistochemical staining for synaptophysin was stongly positive (Figure 2). Chromogranin was also positive. Subsequent chemotherapy treatment included carboplatin and etoposide.

Figure 1).

Trebecular/insular arrangement of high-grade malignancy of hepatic flexure with monomorphous large epithelioid cells with an open nuclear chromatin pattern and a high mitotic/apoptotic rate. Hematoxylin and eosin stain (original magnification ×200)

Figure 2).

Immunohistochemical stain for synaptophysin showing strong cytoplasmic positivity in the malignant cells. Original magnification ×200

DISCUSSION

This patient developed four primary malignancies over two decades, including a highly aggressive and poorly differentiated large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the colon. These unusual cancers accounted for less than 1% of all colorectal malignancies reported over more than a decade from Memorial Sloan-Kettering in New York (USA) (1) and are distinct from well-differentiated carcinoid tumours (or neuroendocrine tumours using the WHO schema). Neuroendocrine carcinomas can be further subdivided into small and large cell types based on their histological and immunohistological features, and most stain positively for markers such as synaptophysin and chromogranin (1). Approximately 70% of neuroendocrine carcinomas present with metastatic disease and are associated with a dismal prognosis, with a reported mean survival of approximately 10 months (1). In spite of scheduled surveillance examinations for dysplasia in high-risk populations, such as long-standing ulcerative colitis (2), highly aggressive neuroendocrine carcinomas have been documented. In some patients, combination platinum and etoposide therapy has been associated with long-term survival (3).

Many anticancer agents have been shown to be carcinogenic, mutagenic and teratogenic in animal and in vitro test systems, while epidemiological studies have noted the association of second neoplasms with specific chemotherapy agents (4). Human exposure has also been a concern, particularly as an occupational exposure in the manufacture, preparation and administration of anticancer agents, including medical staff (4). Recently, concerns have also been expressed regarding the development of malignancies after rituximab, a CD20 monoclonal antibody that has been used effectively in the treatment of B-cell lymphoma (5). In 26 previously reported cases of a second malignancy after initiation of ritixumab treatment, the median time period was five months with a range of one to 40 months (5). Further follow-up studies of patients treated with these regimens are needed.

The Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology is now considering a limited number of submissions for IMAGE OF THE MONTH. These are based on endoscopic, histological, radiological and/or patient images, which must be anonymous with no identifying features visible. The patient must consent to publication and the consent must be submitted with the manuscript. All manuscripts should be practical and relevant to clinical practice, and not simply a case report of an esoteric condition. The text should be brief, structured as CASE PRESENTATION and DISCUSSION, and not more than 700 words in length. A maximum of three images can be submitted and the number of references should not exceed five. The submission may be edited by our editorial team.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bernick PE, Klimstra DS, Shia J, et al. Neuroendocrine carcinomas of the colon and rectum. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:163–9. doi: 10.1007/s10350-003-0038-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freeman HJ, Berean K. Lethal neuroendocrine carcinoma in ulcerative colitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:5882–3. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.5882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Power DG, Asmis TR, Tang LH, Brown K, Kemeny NE. High-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma of the colon, long-term survival in advanced disease. Med Oncol. 2010 Sep 14; doi: 10.1007/s12032-010-9674-1. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sorsa M, Anderson D. Monitoring of occupational exposure to cytostatic anticancer agents. Mutat Res. 1996;355:253–61. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(96)00031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aksoy S, Arslan C, Harputluoglu H, Dizdar O, Altundag K. Malignancies after rituximab treatment: Just coincidence or more? J BUON. 2011;16:112–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]