Abstract

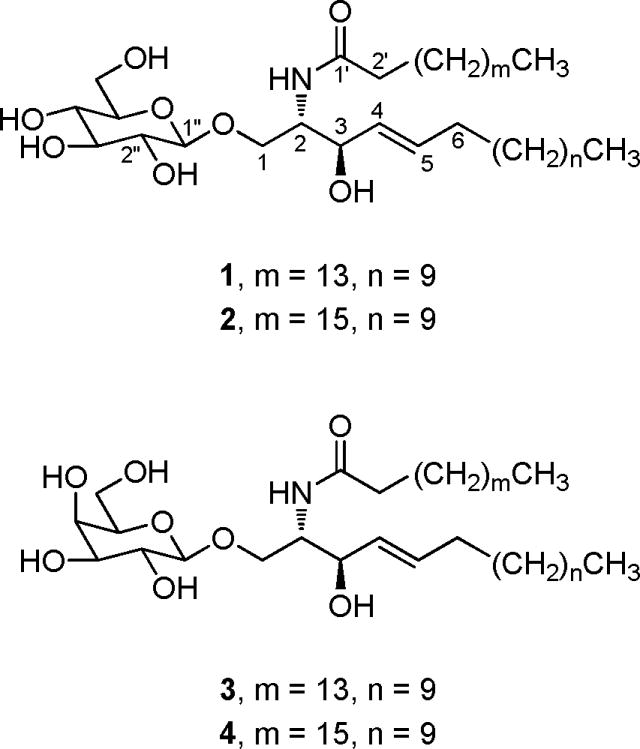

The cancer cell line bioassay-guided separation of an extract from the marine mollusk Turbo stenogyrus led to the isolation of four new cerebrosides designated turbostatins 1–4 (1–4). The structure of each glycolipid was determined by interpreting results of a series of HR-APCI-MS and NMR (1D and 2D) spectral analyses. All four turbostatins exhibited significant (GI50 0.15–2.6 μg/ml) cancer cell growth inhibition against the murine P388 lymphocytic leukemia and a panel of human cancer cell lines.

In 1965–1966, we began the first systematic investigation of marine organisms2 as potential sources of new, structurally unique, and very effective anticancer drugs.3a One of the early (1968) leads uncovered in our geographically far-reaching exploratory evaluation of various marine organisms was the Asian topshell snail Turbo stenogyrus3a,4 (phylum Mollusca, gastropod family Trochidae) collected in Taiwan. In Asia T. stenogyrus is well known as the home shell5 for hermit crabs.6 More generally, topshells are known for the use of some species in the manufacture of pearl ornaments and as a seafood in the Caribbean and Central America. Some (e.g. T. pica) of these algae feeders have been reported to contain toxic tissue.2

We soon found the soft tissue (0.5 kg) from T. stenogyrus to give a 2-propanol extract which displayed strong activity (T/C 177 at 400 mg/kg) against the murine P388 lymphocytic leukemia (in vivo).3a,4 By the summer of 1971 we were able to proceed with the 2-propanol extract from 22.7 kg of T. stenogyrus, and with separation techniques then available, isolated taurine as one of the anticancer constituents.4 Evaluation of taurine using P388 in vivo at dose levels from 4.0 to 800 mg/kg led to T/C values that never exceeded 123 (i.e., 23% increase in median survival time). Furthermore, taurine was found inactive against the in vivo L-1210 lymphoid leukemia and human epidermoid carcinoma of the nasopharynx (KB)7 cell line. As noted at the time,4 we planned to reinvestigate the T. stenogyrus lead when bioassay and chemical separation techniques had improved. We now report the isolation and structural elucidation of four new cancer cell growth inhibitory glycosphingolipids from T. stenogyrus designated turbostatins 1–4 (1–4).

Results and Discussion

The further evaluation of T. stenogyrus fractions was greatly assisted by the subsequent availability of the P388 cell line and human cancer cell lines for bioassay-directed separations, especially combined with advances in general separation procedures and HPLC equipment. Accordingly, another aliquot of the 1971 2-propanol extract of Turbo stenogyrus was first subjected to a 9:1→3:2 CH3OH-H2O/hexane → CH2Cl2 solvent partition sequence. The final active methylene chloride extract (P-388: ED50 3.52 μg/mL) was carefully fractionated by an extensive series of separations involving column gel permeation (Sephadex LH-20), partition chromatography, and a final isolation by reverse-phase HPLC columns on Zorbax SB-C18 in 85:15 CH3OH-H2O. These procedures afforded colorless glycosphingolipids 1–4 as amorphous solids.

The turbostatin 1 (1) molecular formula was assigned C38H74NO8 on the basis of high-resolution APCI mass ([M + H]+ at m/z 672.53855), 1H- and 13C-NMR spectral analyses (Table 1). An IR absorption band at 3393 cm−1 indicated the presence of hydroxyl groups. The typical IR absorptions at 1630 and 1537 cm−1 suggested an amide linkage, which was confirmed by a nitrogen-attached carbon signal at δ 55.05 and a carbonyl signal at δ 173.32 in the 13C-NMR spectrum. The 1H-NMR spectrum exhibited a doublet at δ 8.35 (J = 7.5 Hz) due to an NH proton, which was exchangeable with D2O; a broad singlet at δ 1.21 (methylene protons); a triplet at δ 0.85 (two terminal methyls); an anomeric proton at δ 4.96 (J = 8.2 Hz), and carbinol protons appearing as multiplets between δ 3.90–4.82, suggesting a glycosphingolipid structure.8–11 The 1H-NMR spectrum also showed two olefinic proton signals at δ 5.97 (1H, dd, J = 15.0, 6.0 Hz, H-4), and 5.83 (1H, dt, J = 15.2, 6.0 Hz, H-5), attributable to the presence of one disubstituted double bond. The amino alcohol fragment was identified as a sphingosine unit by the characteristic signals that appeared in the 1H- and 13C-NMR spectra, especially owing to the presence of a typical Δ4 double bond.8,9 The large vicinal coupling constants of H-4 and H-5 (J = 15.0 Hz) clearly indicated an E-geometry for the double bond.9,10

Table 1.

1H- and 13C-NMR Spectral Assignments (δ/ppm) for Turbostatins 1 and 2 in Py-d5

| Position | δH | δC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | |

| Lipid Base Unit | ||||

| 1a | 4.82 (m) | 4.82 (m) | 70.46 | 70.42 |

| 1b | 4.23 (m) | 4.22 (m) | ||

| 2 | 4.81 (m) | 4.80 (m) | 55.05 | 55.02 |

| 3 | 4.75 (m) | 4.75 (m) | 72.58 | 72.57 |

| 4 | 5.98 (dd, 6.0, 15.0) | 5.97 (dd, 6.0, 15.2) | 132.20 | 132.21 |

| 5 | 5.85 (dt, 6.0, 15.0) | 5.83 (dt, 6.0, 15.2) | 132.51 | 132.49 |

| 6 | 2.03 (q, 7.0) | 2.01(q, 7.1) | 32.71 | 32.71 |

| 7~15 | 1.21 (brs) | 1.21 (brs) | 22.9~32.1 | 22.9~32.1 |

| 16 | 0.85 (t, 8.6) | 0.85 (t, 8.6) | 14.25 | 14.24 |

| NH | 8.35 (d, 7.5) | 8.37 (d, 7.8) | ||

| N-Acyl Unit | ||||

| 1′ | 173.32 | 173.30 | ||

| 2′ | 2.41 (t, 7.0) | 2.41 (t, 7.0) | 32.71 | 32.70 |

| 3′ | 1.80 (m) | 1.80 (m) | 26.37 | 26.39 |

| 4′~15′ or 4′~17′ | 1.21 (brs) | 1.21 (brs) | 22.9~32.1 | 22.9~32.1 |

| 16′ or 18′ | 0.85 (t, 8.6) | 0.85 (t, 8.6) | 14.25 | 14.24 |

| Glycoside | ||||

| 1″ | 4.96 (d, 8.2) | 4.96 (d, 8.1) | 105.46 | 105.44 |

| 2″ | 4.06 (dd, 8.4, 9.6) | 4.04 (dd, 8.1, 9.3) | 75.15 | 75.15 |

| 3″ | 4.24 (m) | 4.24 (m) | 78.48 | 78.48 |

| 4″ | 4.37 (m) | 4.37 (m) | 71.64 | 71.63 |

| 5″ | 3.90 (m) | 3.91 (m) | 78.47 | 78.46 |

| 6a″ | 4.51 (dd, 5.1, 11.7) | 4.50 (dd, 5.0, 11.6) | 62.74 | 62.74 |

| 6b″ | 4.20 (dd, 2.3, 11.7) | 4.22 (dd, 2.3, 11.6) | ||

In the 13C-NMR spectrum the carbon resonances appeared at δ 62.74 (CH2), 71.64 (CH), 75.15 (CH), 78.47 (CH), 78.48 (CH), and 105.46 (CH) revealing the presence of a β-glucopyranoside.12 The anomeric proton at δ 4.96 (d, J = 8.2 Hz) correlated to the carbon signal at δ 105.46 in the HMQC spectrum, further confirming the β-configuration of the glucoside unit. The length of the lipid (sphingoid base) base and the lipid amide were determined by APCI-MS. In addition to the quasimolecular ion at m/z 672 [M + H]+, the APCI spectrum of turbostatin 1 exhibited an intense fragment peak at m/z 510 which was produced by elimination of the glucosyl unit from the protonated molecular ion. The loss of palmitoylamide from the molecular ion gave rise to the fragment at m/z 254. The typical fragment ion at m/z 384 was formed by elimination of decene from that at m/z 510 through McLafferty rearrangement.13,14 Therefore, the number of carbons in the lipid base and lipid amide were both determined to be 16.

The linkages of the three component units of turbostatin 1 were deduced from the HMBC spectrum. The carbon signal at δ 173.32 (C-1′) correlated with the proton signals at δ 4.81 (H-2) and 2.41 (H-2′). The proton signal at δ 4.81 (H-2) gave crosspeaks with the carbon signal at δ 72.58 (C-3) and 70.46 (C-1). In addition, the latter also correlated with the proton signal at δ 4.96 (C1″). The carbon signal at δ 72.58 (C-3) showed crosspeaks with the proton signals at δ 5.98 (H-4) and 5.85 (H-5). From these analyses, the structure of turbostatin 1 was elaborated and the overall assignments (Table 1) of 1H-NMR and 13C-NMR data were unambiguously made based on the 1H-1H COSY, TOCSY, HMQC, and HMBC spectra. By considering biogenetic relationships,15 steric factors and the chemical shift of H-2, the chemical shifts of the carbon signals of C-1 to C-3 and C-1′ may be utilized to determine the absolute stereochemistry of glucosphingolipids and sphingolipids.16–18 The proton signal at δ 4.81 (H-2) and the carbon signals at δ 70.46 (C-1), 55.05 (C-2), 72.58 (C-3), and 173.32 (C-1′) of turbostatin 1 were in good agreement with those reported for glycosphingonines (as model structures) with the 2S,3R configuration.8–10,14,19 The optical rotation of turbostatin 1 ([α]23D + 10.2°) was very close to that of 1-O-(β-D-glucopyranosyl)-D-(+)-(2S, 3R)-2-(docosanoylamide)-1,3-eicosanediol ([α]27D + 8.6).8 All of these considerations were used to assign turbostatin 1 as 1-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-2S-hexadecanoylamino-3R-hydroxy-4E-hexadecene.

As with turbostatin 1, the molecular formula of turbostatin 2 (2) was assigned C40H78NO8 on the basis of high-resolution APCI mass spectroscopy ([M + H]+ at m/z 700.57498) and the results of 1H- and 13C-NMR spectral interpretations (Table 1). The NMR results were found to be essentially identical to those of amide 1, which confirmed that turbostatin 2 (2) was also a glycosphingolipid and differed only in the length of the lipid base and lipid amide units. In addition to the quasimolecular ion at m/z 700 [M + H]+, the APCI spectrum of ceramide 2 exhibited an intense fragment peak at m/z 538 which was produced by elimination of the glucosyl unit from the protonated molecular ion. The loss of octadecoylamide from the molecular ion gave rise to the fragment at m/z 254. The typical fragment ion at m/z 412 was formed by elimination of decene through McLafferty rearrangement.13,14 Therefore, the number of carbons in the lipid base and lipid amide were determined to be 16 and 18, respectively. Thus, turbostatin 2 was assigned structure 2.

The molecular formula of turbostatin 3 (3) was found to be C38H74NO8 on the basis of high-resolution APCI mass spectroscopy ([M + H]+ at m/z 672.54142) as well as 1H- and 13C-NMR spectral results (Table 2). Again, the 1H- and 13C-NMR spectra were found to be nearly identical to those of turbostatins 1 and 2 except for the glycoside signals and confirmed that turbostatin 3 (3) was also a glycosphingolipid. In the 13C-NMR spectrum the glycoside unit carbon resonances appeared at δ 62.34 (CH2), 70.21 (CH), 72.71 (CH), 75.38 (CH), 77.07 (CH), and 106.47 (CH) revealing the presence of a β-galactopyranoside.12 The anomeric proton at d 4.89 (d, J = 7.5 Hz) correlated to the carbon signal at δ 106.47 in the HMQC spectrum, further confirming the β-configuration of the galactose unit. The APCI-MS spectrum of cerebroside 3 also exhibited three fragment peaks at m/z 510, 384 and 254, which suggested the number of carbons in the lipid base and lipid amide were both 16. Therefore, structure 3 was determined to represent turbostatin 3.

Table 2.

1H- and 13C-NMR Spectral Assignments (δ/ppm) for Turbostatins 3 and 4 in Py-d5

| Position | δH | δC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | |

| Lipid Base Unit | ||||

| 1a | 4.81 (m) | 4.82 (m) | 70.44 | 70.45 |

| 1b | 4.24 (m) | 4.23 (m) | ||

| 2 | 4.80 (m) | 4.81 (m) | 55.04 | 55.03 |

| 3 | 4.75 (m) | 4.75 (m) | 72.60 | 72.59 |

| 4 | 5.99 (dd, 6.0, 15.2) | 5.98 (dd, 6.0, 15.0) | 132.15 | 132.18 |

| 5 | 5.85 (dt, 6.0, 15.2) | 5.83 (dt, 6.0, 15.0) | 132.50 | 132.49 |

| 6 | 2.03 (q, 7.2) | 2.01(q, 7.0) | 32.72 | 32.70 |

| 7~15 | 1.21 (brs) | 1.21 (brs) | 22.9~32.1 | 22.9~32.1 |

| 16 | 0.85 (t, 8.6) | 0.85 (t, 8.6) | 14.26 | 14.25 |

| NH | 8.37 (d, 7.7) | 8.36 (d, 7.8) | ||

| N-Acyl Unit | ||||

| 1′ | 173.33 | 173.33 | ||

| 2′ | 2.41 (t, 7.2) | 2.41 (t, 7.1) | 32.71 | 32.70 |

| 3′ | 1.80 (m) | 1.80 (m) | 26.38 | 26.38 |

| 4′~15′ or 17′ | 1.21 (brs) | 1.21 (brs) | 22.9~32.1 | 22.9~32.1 |

| 16′ or 18′ | 0.85 (t, 8.6) | 0.85 (t, 8.6) | 14.26 | 14.25 |

| Glycoside | ||||

| 1″ | 4.89 (d, 7.5) | 4.88 (d, 7.3) | 106.47 | 106.46 |

| 2″ | 4.52 (dd, 7.5, 9.5) | 4.52 (dd, 7.5, 9.4) | 72.71 | 72.71 |

| 3″ | 4.16 (dd, 3.0, 9.5) | 4.14 (dd, 3.0, 9.4) | 75.38 | 75.40 |

| 4″ | 4.56 (d, 3.0) | 4.55 (3.0) | 70.21 | 70.22 |

| 5″ | 4.07 (dd, 6.0, 9.0) | 3.07 (dd, 6.2, 8.9) | 77.07 | 77.06 |

| 6″ | 4.44 (m) | 4.44 (m) | 62.34 | 62.35 |

The molecular formula of turbostatin 4 (4) was assigned C40H78NO8 based on the spectral data sequence: [M + H]+ at m/z 700.57537 and as recorded in Table 2 which were found to be essentially identical with that of turbostatin 3 differing only in the length of the lipid base and lipid amide. The APCI-MS spectrum of amide 4 also exhibited three fragment peaks at m/z 538, 412 and 254 as already found for amide 2. This indicated the number of carbons in the lipid base and lipid amide were also 16 and 18, respectively, and allowed assignment of structure 4 to turbostatin 4.

Turbostatins 1–4 were evaluated against the murine P388 lymphocytic leukemia cell line and a minipanel of human cancer cell lines (see Table 3) and were found to exhibit significant cancer cell growth inhibition against each cell line. That was a promising result since some ceramides (parent is an 18 carbon lipid base, 14 carbon lipid amide) and derived hexose glycosides such as glucocerebrosides (e.g., 1 and 2) and galactocerebrosides (e.g., 3 and 4) function as a cellular second messenger and intermediary in a variety of important cell functions such as apoptosis, cell senescence and terminal cell differentiation.20 Ceramide is also known to stimulate mitogen-activated protein kinase21 through binding to protein kinase c-Raf,22 and some cerebrosides are known to possess anticancer, antiviral, antifungal, antimicrobial, Cox-2 inhibitory, immunostimulative and immunosuppressive activities. Some of these properties would appear promising for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease.23 Interestingly, α-alactosylceramides have been shown earlier to have anticancer activity.24–27 As an illustration, KRN7000 has been shown to display remarkable activity against a disparate group of diseases, such as cancer, including melanoma, pancreatic and colon cancer, as well as malaria, juvenile diabetes, hepatitis B and autoimmune encephalomyelitis, using in vivo versions of these diseases.27 We intend to proceed with further biological evaluation of turbostatins 1–4 as these new glycocerebrosides may have a useful role in inhibiting the sphingolipid biochemical pathways of the cancer cell.

Table 3.

Murine P388 Lymphocytic Leukemia Cell Line and Human Cancer Cell Line Inhibition Values (GI50 expressed in μg/mL) for Turbostatins 1–4a

| Cancer cell lineb | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P388 | 0.27 | 0.15 | 0.25 | 0.29 |

| MXPC-3 | 0.71 | 1.0 | 1.6 | 0.93 |

| MCF-7 | 0.44 | 0.39 | 0.48 | 0.44 |

| SF268 | 0.98 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.5 |

| NCI-H460 | 0.34 | 0.53 | 0.55 | 0.49 |

| KML20L2 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.48 | 0.41 |

| DU-145 | 1.6 | 1.7 | 2.6 | 2.6 |

In DMSO.

Cancer type: P388 (lymphocytic leukemia); BXPC-3 (pancreas adenocarcinoma); MCF-7 (breast adenocarcinoma); SF268 (CNS glioblastoma); NCI-H460 (lung large cell); KM20L2 (colon adenocarcinoma); DU-145 (prostate carcinoma).

Experimental Section

General Experimental Methods

Melting points were measured using an Olympus electrothermal melting point apparatus and are uncorrected. IR spectra were recorded with a Thermo Nicolet Avatar 360 infrared spectrometer. NMR spectra were obtained with a Varian XL-300 or a Varian UNITY INOVA-500 spectrometer with tetramethylsilane (TMS) as an internal reference. High-resolution mass spectra were obtained using a JEOL LCMate magnetic sector instrument in the APCI positive mode, with a polyethylene glycol reference.

All chromatographic solvents were redistilled. Sephadex LH-20 used for partition column chromatography was obtained from Pharmacia Fine Chemicals AB. Analytical HPLC was conducted with a Hewlett-Packard Model 1050 HPLC coupled with a Hewlett-Packard diode-array detector. Semipreparative HPLC was performed on a Waters Deltaprep-600 instrument on 9.4 × 250 mm columns of Zorbax SB-C18.

Turbo stenogyrus

The topshell T. stenogyrus (phylum Mollusca, class Gastropoda, subclass Prosobronchia) is a member of the Turbinidae family in the order Archaeogastropoda. A summer of 1971 recollection (22.7 kg; from along the coast of Taiwan) of T. stenogyrus was employed in the present study and supplied by Mr. Elliot Glanz, The Butterfly Company, Brooklyn, New York, NY, in 1968. The voucher specimen is maintained in our Institute, and the taxonomic authority was Dr. I. E. Wallen, Smithsonian Oceanographic Sorting Center, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D. C., 20560.

Extraction and Initial Separation of T. Stenogyrus

The snail portion of the 1971 recollection T. stenogyrus was extracted with 2-propanol. The extract (the long period of storage was in a tightly sealed glass container, maintained in the dark at ca. 20°C) was dissolved in CH3OH-H2O (9:1) and the solution filtered to remove insoluble material. The resulting solution was partitioned four times between hexane and 9:1 CH3OH-H2O. The hexane layer was removed and concentrated to yield 13.3g (P388 ED50 60 μg/mL) of black-brown material. The CH3OH-H2O phase was diluted to give a ratio of 3:2 (by addition of H2O) and extracted four times with CH2Cl2, the CH2Cl2 layer was concentrated to afford a black oily P388-active (14.7g, ED50 3.52 μg/mL) fraction. The remaining CH3OH-H2O solution was P388 cell line inactive.

Isolation of Turbostatins 1–4 (1–4)

A 14.6-g aliquot of the P388-active CH2Cl2 fraction was partially dissolved in CH3OH, and the solution was filtered and separated on a Sephadex LH-20 column with CH3OH as eluent. Ten fractions were obtained. One of the fractions (2.5 g, ED50 1.25 μg/mL) was further separated on a Sephadex LH-20 column in CH3OH-CH2Cl2 (3:2) to yield seven fractions. A 1.4-g fraction with ED50 0.30 μg/mL was rechromatographed on a Sephadex LH-20 column in hexane- CH3OH-2-propanol (8:1:1). Two fractions obtained from this step showed P388 activity, and a 180-mg fraction with ED50 0.76 μg/mL was further separated on a Sephadex LH-20 column in hexane-toluene-acetone- CH3OH (1:4:3:4). Six active fractions were combined and rechromatographed on a Sephadex LH-20 column using hexane-ethanol-toluene-CH2Cl2 (17:1:1:1) as eluent. Four active fractions were obtained, recombined and rechromatographed on a Sephadex LH-20 column with hexane-EtOAc-CH3OH (4:5:1) as eluent. All five fractions obtained from this step showed P388 activity and a 56-mg fraction with ED50 0.21 μg/mL, a dark-brown material, was separated on a semipreparative reversed-phase HPLC Zorbax SB C18 column with 85:15 CH3OH-H2O (a flow rate of 4 mL/min and the UV detector set at 208 nm). Turbostatins 1 (1) and 2 (2) were obtained in the following order: 1 (10.1 mg) at 20.5 min and 2 (11.2 mg) at 25.1 min. A103-mg fraction with ED50 0.56 μg/mL was separated on a semipreparative reversed-phase HPLC Zorbax SB C18 column with 85:15 CH3OH-H2O (a flow rate of 4 mL/min and the UV detector set at 208 nm). The result was that turbostatins 3 (3) and 4 (4) were obtained in the following order: 3 (11.6 mg) at 23.7 min and 4 (8.3 mg) at 28.5 min. All four new compounds were colorless and had very limited solubility in CH3OH, CH2Cl2, CH3CN, and H2O.

Turbostatin 1 (1) 1-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-2S-hexadecanoylamino-3R-hydroxy-4E-hexadecene

colorless amorphous solid; mp 207–209°C; [α]23D + 10.2° (c 0.10, pyridine); IR (KBr)νmax 3393 (OH), 2950, 1630 (C=O), 1537, 1450, 1083, 1032, and 720 cm−1; 1H- and 13C-NMR data see Table 1; APCI-MS (positive) m/z 672 [M+H]+, 654, 510, 492, 384, 254; APCI-HRMS (positive) m/z 672.53855 [M+H]+ (calcd for C38H74NO8, 672.54142).

Turbostatin 2 (2) 1-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-2S-octadecanoylamino-3R-hydroxy-4E-hexadecene

colorless amorphous solid; mp 209–210°C; [α]23D + 10.7° (c 0.10, pyridine); IR (KBr)νmax 3394 (OH), 2950, 1631 (C=O), 1538, 1450, 1084, 1030, and 720 cm−1; 1H- and 13C-NMR data appear in Table 1; APCI-MS (positive) m/z 700 [M+H]+, 682, 538, 520, 412, 254; APCI-HRMS (positive) m/z 700.57498 [M+H]+ (calcd for C38H74NO8, 700.57272).

Turbostatin 3 (3) 1-O-β-D-galactopyranosyl-2S-hexadecanoylamino-3R-hydroxy-4E-hexadecene

colorless amorphous solid; mp 213–214°C; [α]23D – 6.3° (c 0.10, pyridine); IR (KBr)νmax 3395 (OH), 2951, 1633 (C=O), 1537, 1450, 1085, 1031 and 720 cm−1; 1H- and 13C-NMR data refer to Table 2; APCI-MS (positive) m/z 672 [M+H]+, 654, 510, 492, 384, 254; APCI-HRMS (positive) m/z 672.53979 [M+H]+ (calcd for C38H74NO8, 672.54142).

Turbostatin 4 (4) 1-O-β-D-galactopyranosyl-2S-octadecanoylamino-3R-hydroxy-4E-hexadecene

colorless amorphous solid; mp 214–215°C; [α]23D - 6.5° (c 0.10, pyridine); IR (KBr)νmax 3394 (OH), 2950, 1632 (C=O), 1538, 1451, 1084, 1030 and 720 cm−1; 1H- and 13C-NMR data see Table 2; APCI-MS (positive) m/z 700 [M+H]+, 682, 538, 520, 412, 254; APCI-HRMS (positive) m/z 700.57537 [M+H]+ (calcd for C40H78NO8, 700.57272).

Cancer Cell Line Methods

The National Cancer Institute’s standard sulforhodamine B assay was used to assess inhibition of human cancer cell growth as previously described.28 The murine P388 lymphocytic leukemia cell line results were obtained using 10% horse serum/Fisher medium with incubation for 24 hrs. Serial dilutions of the compounds were added, and after 48 hrs, cell growth inhibition (ED50) was calculated using a Z1 Coulter particle counter.

Acknowledgments

For the very necessary financial assistance we are pleased to acknowledge Grant RO1 CA90441-03-04 awarded by the Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis, NCI, DHHS, the Arizona Disease Control Research Commission, the Fannie E. Rippel Foundation, G. L. and D. Tooker, Dr. A. D. Keith, J. W. Kieckhefer Foundation, the Margaret T. Morris Foundation, the Robert B. Dalton Endowment Fund, P. J. Trautman, J. and E. Reyno, Dr. J. C. Budzinski, as well as Mr. E. Glanz and The Butterfly Co. for assistance with the field biology. For other helpful assistance, we are pleased to thank Drs. J. L. Hartwell, F. Hogan, H. A. Fehlmann, J. M. Schmidt, J.-C. Chapuis, D. L. Doubek, Mr. L. Williams, Mr. M Dodson and a referee for suggesting reference 27 as well as NSF grant CHE 9808678 for the high-field NMR equipment.

Footnotes

Dedicated to the memory of Dr. Cecil R. Smith, Jr. (1924–2004), a productive pioneer in the discovery of naturally-occurring anticancer drugs.

References and Notes

- 1.For contribution 544, refer to Bai R, Covell DG, Kepler JA, Copeland TD, Nguyen NY, Pettit GR, Hamel E. J Biol Chem. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402110200. published.

- 2.Halstead BW. Poisonous and Venomous Marine Animals of the World. Vol. 1. U. S. Government Printing Office; Washington, D. C: 1965. p. 708. [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Pettit GR, Day JF, Hartwell JL, Wood HB. Nature. 1970;227:962–963. doi: 10.1038/227962a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Schwartsmann G, Brondani da Rocha A, Mattei J, Lopes RM. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2003;12:1367–1383. doi: 10.1517/13543784.12.8.1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Haefner B. DDT. 2003;8:536–544. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(03)02713-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Kingston DGI, Newman DJ. Drug Discovery & Dev. 2002;15:304–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Luesch H, Harrigan GG, Goetz G, Horgen FD. Curr Med Chem. 2002;9:1791–1806. doi: 10.2174/0929867023369051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pettit GR, Ode RH, Harvey TB., III Lloydia. 1973;36:204–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Kono N, Yamakawa H. Bull Fisheries Res Agency. 2002:19–24. [Google Scholar]; (b) Poulicek M. Malacologia. 1982;22:235–239. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murata K, Watanabe S, Takagi K. Mer-Tokyo. 1988;26:29–35. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pettit GR, Houghton LE, Rogers NH, Coomes RM, Berger DF, Reucroft PR, Day JF, Hartwell JL, Wood HB. Experientia. 1971;28:382. doi: 10.1007/BF02008286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Babu UV, Bhandari SPS, Garg HS. J Nat Prod. 1997;60:732–734. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kawatake S, Nakamura K, Inagaki M, Higuchi R. Chem Pharm Bull. 2002;50:1091–1096. doi: 10.1248/cpb.50.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sitrin RD, Chan G, Dingerdissen J, Debrosse C, Mehta R, Roberts G, Rottschaefer S, Staiger D, Valenta J, Snader KM, Stedman RJ, Hoover JRE. J Antibiot. 1988;41:469–480. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.41.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen JH, Cui GY, Liu JY, Tan RX. Phytochemistry. 2003;64:903–906. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(03)00421-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bock K, Pederson C. In: Advances in Carbohydrate Chemistry and Biochemistry. Jipson RS, Horfon D, editors. Vol. 41. Academic Press; New York: 1983. pp. 27–46. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kong LD, Abliz Z, Zhou CX, Li LJ, Cheng CHK, Tan RX. Phytochemistry. 2001;58:645–651. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(01)00176-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen X, Wu YL, Chen D. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43:3529–3532. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kolter T, Sandhoff K. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1999;38:1532–1568. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19990601)38:11<1532::AID-ANIE1532>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kang SS, Kim JS, Xu YN, Kim YH. J Nat Prod. 1999;62:1059–1060. doi: 10.1021/np990018r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sugiyama S, Honda M, Komoro T. Liebigs Ann Chem. 1990:1069–1078. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sugiyama S, Honda M, Higuchi R, Komoro T. Liebigs Ann Chem. 1991:349–356. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jung JH, Lee CO, Kim YC, Kang SS. J Nat Prod. 1996;59:319–322. doi: 10.1021/np960201+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pushkareva M, Obeid L, Hannun Y. Immunol Today. 1994;16:294. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(95)80184-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raines MA, Kolesnick RN, Golde DW. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:14572–14575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huwiler A, Brunner J, Hummel R, Vervoordeldonk M, Stabel S, van den Bosch H, Pfeilschifter J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:6959–6963. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.14.6959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tan RX, Chen JH. Nat Prod Rep. 2003;20:509–534. doi: 10.1039/b307243f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Plettenburg O, Boddmer-Narkevitch V, Wong CH. J Org Chem. 2002;67:4559. doi: 10.1021/jo0201530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morita M, Motoki K, Akimoto K, Natori T, Sakai T, Sawa E, Yamaji K, Koezaka Y, Kobayashi E, Fukushima H. J Med Chem. 1995;38:2176. doi: 10.1021/jm00012a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Motoki K, Kobayashi E, Uchida T, Fukushima H, Koezuka Y. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1995;140:705. doi: 10.1016/0968-0896(96)00049-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang G, Schmieg J, Tsuji M, Franck RW. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2004;43:3818–3822. doi: 10.1002/anie.200454215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Monks A, Scudiero D, Skehan P, Shoemaker R, Paull K, Vistica D, Hose C, Langley J, Cronise P, Vaigro-Wolff A, et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1991;83:757–766. doi: 10.1093/jnci/83.11.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]