Abstract

Objective

To compare symptom expression in primarily middle-aged (<60) and older (60+) depressed patients and determine if symptom profiles differed by age.

Methods

Patients diagnosed with major depression (n=664) were screened using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies – Depression Scale and sections of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule. Patients were separated into homogeneous clusters based on symptom endorsement using latent class analysis.

Results

Older patients were less likely to endorse crying spells, sadness, feeling fearful, being bothered, or feeling life a failure, but were more likely to endorse poor appetite and loss of interest in sex. Older patients were also less likely to report enjoying life, feeling as good as others, feeling worthless, wanting to die and thinking about suicide. In two latent class models with depressive symptoms as indicators, three-class models best fit the data. Profiles supported heterogeneity in symptom expression. Clusters differed by age when other demographic, clinical, health and social variables were controlled, but did not support age-specific symptom profiles. Overall, older patients had later age of onset, had fewer lifetime spells, were more likely to have ever received ECT and were less likely to have comorbid anxiety. Older patients also had more cognitive impairment, health conditions, and mobility limitations, but had higher levels of subjective social support and had experienced fewer stressful life events.

Conclusions

There are age differences in symptom endorsement between younger/middle-aged and older patients with major depression. The data, however, did not identify a symptom profile unique to late-life depression.

Keywords: depression, symptoms, age differences, latent class analysis

Introduction

The prevalence of major depression is lower in later life (Blazer and Hybels, 2005; Kessler et al., 2010). These observed age differences in prevalence have lead to discussions whether depression manifests itself differently in older adults. For example, Gallo and colleagues reported the prevalence of nondysphoric depression or depression without sadness observed at older ages (Gallo et al., 1994; Gallo et al., 1997).

Few studies have examined age differences in symptom expression among patients with major depression. Brodaty and colleagues reported older patients with major depression were more likely to be psychotic and agitated and less likely to have a family history of depression or personality inadequacies compared to younger patients. They also found that elderly depressives were more likely to have melancholic depression, appetite and weight loss, and overall more severe depression (Brodaty et al., 1997; Brodaty et al., 1991). They recently reported that older patients exhibited more delusions, motor agitation, severe guilt, and hypochondriasis, and less hypersomnia (Brodaty et al., 2005). Other researchers, however, have found agitation and psychotic tendencies were not more common in older depressives (Musetti et al., 1989). Similarly, Blazer and colleagues did not find age differences in melancholic depression among psychiatric inpatients who were not medically ill or cognitively impaired (Blazer et al., 1987).

Age differences in depressive symptoms have been reported from general population studies. Gallo and colleagues reported even controlling for overall level of depression, older adults were less likely to endorse symptoms of dysphoria, anorexia, weight change or agitation while being more likely to endorse sleep difficulties, tiredness and thoughts of death (Gallo et al., 1994). Christensen and colleagues also found older adults were less likely to report worry, irritability and headaches/backaches and feeling ‘worked up’, while age was positively associated with breathlessness. Reports of waking early, slowing down, feeling so miserable it interfered with sleep, not caring if woke up, hopelessness, loss of interest and suicidal thoughts increased with age, while reported weight loss decreased with age (Christensen et al., 1999). Some have reported somatic complaints are more prominent among older than younger adults, especially older women (Berry et al., 1984). Gatz and colleagues, however, examined age differences in CES-D symptoms and found adults 70 or older scored higher only on lack of well-being compared to younger adults, while younger adults scored higher on depressed mood. Somatic symptoms were not elevated in older adults (Gatz and Hurwicz, 1990). While these community-based studies are informative, these differences may not easily translate to age differences among patients with major depression.

Our objective was to compare age differences in symptom expression between primarily middle-aged and older patients diagnosed with major depression at the time of the index episode using two qualitatively different measures of depressive symptoms. We chose two different measures not for comparison but to provide two perspectives on symptom expression. A secondary objective was to use latent class analyses (LCA) to separate patients into homogeneous clusters based on symptom endorsement and determine if the clusters differed by age. We hypothesized that older patients would differ from middle-aged patients in their symptom expression. We also hypothesized that a multi-cluster model would fit the data better than a single-cluster model for both measures, supporting heterogeneity within a mixed age sample of patients with major depression. We hypothesized that the clusters would differ by average age of the patients as well as by levels of exposure to potential risk factors.

Heterogeneity in symptom presentation among adults in the general population has been well documented (Eaton et al., 1989; Lincoln et al., 2007; Sullivan et al., 1998; Sullivan et al., 2002). These studies have usually identified either a high symptom vs. low symptom cluster or one cluster that reflects patients with major depression. We have reported heterogeneity among adults 60+ diagnosed with major depression (Hybels et al., 2011; Hybels et al., 2009) but it is not known how symptom profiles vary within a mixed age sample of adults with major depression and whether there is a unique profile associated with depression in older adults compared to younger/middle-aged adults.

Age differences in symptom expression could reflect differential exposure to risk factors. Jorm and colleagues reported from a community survey that adults 60-64 years of age reported lower levels of mastery, worse self-rated health, and lower levels of education compared to younger adults. In addition, older adults were less likely to report having had a recent illness or injury in the family or a recent crisis at work. Interpersonal problems and being unemployed also declined with age (Jorm et al., 2005). Other factors such as stress and social support linked to depression may vary by age. Ongoing difficulties may have a smaller effect on depression in older adults than younger adults (Bruce, 2002). Older adults may also have smaller social networks but perceive their support as adequate (Blazer and Hybels, 2005). In clinical studies, some adults with late onset major depression have evidence of cerbrovascular disease, leading to a diagnosis of vascular depression, which may present with different symptoms than those with an earlier onset (Alexopoulos et al., 1997a; Alexopoulos et al., 1997b). Depressive symptoms may be different in older compared to younger adults because of comorbid physical illness or cognitive impairment. Kessler and colleagues, however, reported from a community sample that comorbidity of major depression with physical disorders decreased with age despite increasing prevalence of physical disorders with age (Kessler et al., 2010). It is not known how different levels of exposure may differentiate symptom profiles among middle-aged and older adults with major depression.

Identifying heterogeneity in symptom expression between younger/middle-aged and older adults can assist in understanding whether within one categorical diagnosis of depression there can be heterogeneity perhaps due to age-specific etiological factors or clinical presentation, important topics as the nomenclature moves forward (Kraemer, 2007). That is, the rationale for our current study lies in the conceptualization of depression across different age groups.

Methods

Sample design and data collection

Participants were patients diagnosed with major depression enrolled in the Duke Clinical Research Center (CRC) for the Study of Depression in Late Life and ranged in age from 18-90, although patients were predominantly ages 30-50 and 60+ to address the CRC objective of comparing the phenomenology of mid-life to late-life depression.

Patients were screened at enrollment with the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression scale (CES-D) (Radloff, 1977) and administered sections of the NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS) (Robins et al., 1981). A diagnostic team assigned consensus diagnoses. DSM-III (American Psychiatric Association, 1980) was in place at the time of data collection.

To be selected for these analyses, participants had to have diagnosed major depressive disorder (MDD) with their most recent spell within the last 6 months. Patients with bipolar disorder were included if their most recent episode was depression. Of the 909 participants enrolled, 81 were dropped from these analyses because their primary diagnosis did not meet these criteria and 98 patients were removed because their most recent episode was >6 months prior to study enrollment.

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Duke University Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Depression

The CES-D was used in its original format, with patients rating each of 20 symptoms on a score of 0 (rarely/none of the time) to 3 (most/all of the time) to reflect how often the patients were bothered by the symptom in the previous week at the time of enrollment.

The DIS was originally designed to identify cases of major depression in community samples, follows the logic of a diagnostic interview and therefore is qualitatively different from the CES-D. Each symptom had a range of response codes from 1 (not present), 2 (present but below criteria), 3 (due to medication, drugs or alcohol), 4 (due to physical illness), and 5 (above criteria and not due to medication or illness). We assigned codes 0=symptom not endorsed and 1=endorsed. Symptoms endorsed but not present within the two weeks prior to enrollment were coded as 0 to identify only current symptoms.

Demographic data included age, sex, race (White/Other=1, Black=0; less than 1% were Other) and marital status (married=1, not married=0). A measure of education was unavailable. Cognitive status was defined using the number of errors on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (Folstein et al., 1975). The study generally required participants to be cognitively healthy to be able to participate.

The DIS also inquired about number of lifetime spells of depression, coded in these analyses as 0-3, 4-10 and 11+. Forty-one patients who reported more than one lifetime spell but did not know the number were coded with those reporting 4-10 spells since the majority of patients with more than one spell were in this group. Age of onset was used as a continuous variable. A current diagnosis of generalized anxiety (Yes=1/No=0) from the DIS was used also as a covariate. A DDES variable assessed the presence of melancholia by asking what time of day the depression seemed to be the worse – morning, evening or no difference. Finally, we used a variable to indicate whether the patient had ever received ECT (Yes=1/No=0).

Health variables included a list of conditions, five of which were selected for this analysis (diabetes, hypertension, heart trouble, stroke and cancer). Patients indicated if they had the condition and how much it interfered with daily activities. Responses for each condition ranged from 1 to 4 with higher numbers indicating greater interference. The responses were summed and transformed for analytic purposes. We included a variable indicating whether or not (Yes=1/No=0) the patient had one or more limitations in mobility (being able to walk ¼ mile, walk up and down stairs without resting, and get around in the neighborhood).

Social support was measured using the 10-item subjective social support subscale from the Duke Social Support Index (Landerman et al., 1989), which assessed the patient's perception of and satisfaction with social support. Subjective social support was used as a continuous variable, with a possible range from 10 to 29, higher numbers indicating greater support. We also included a measure of stressful life events in these analyses. The total number of twenty events experienced in the past year was used as a continuous variable, with a range from 20 to 40.

Data analysis

We compared age differences on sample characteristics, mean CES-D scores for each symptom and the proportion endorsing each of the depression symptoms from the DIS, comparing those ages 18-59 to those 60+.

We conducted two sets of LCA using clustering techniques with the CES-D symptoms and the DIS items as model indicators. The patients were grouped into clusters so that individuals in one cluster shared similar characteristics and differed from individuals in other clusters with regard to underlying latent characteristics based on responses to the model indicators. LCA uses a model-based approach to cluster analysis in that patients are assigned to the cluster where they had the highest probability of group membership (Magidson and Vermunt, 2002; Vermunt and Magidson, 2002). Cluster numbers are assigned by size. The optimal number of clusters derived from the data is unknown prior to model estimation.

For each measure, we estimated 1-5 cluster models. We used the Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC) fit statistic that takes into account the number of parameters estimated in the model, with a smaller BIC preferable, to identify the model that best fit the data for each measure. We also computed log-likelihood statistics between two nested models to see if an additional cluster significantly improved the model fit. Latent Gold software was used for the LCA (Vermunt and Magidson, 2005).

We output the cluster assignments and compared covariates across clusters for each measure. As a final step we estimated two multinomial logistic regression models with cluster membership as the dependent variable to look at the independent associations between the covariates and cluster membership. SAS analysis software (SAS Institute, 2008) was used for these analyses. All statistical tests were two tailed.

Results

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the 664 patients. The sample varied by age and was predominantly White. With the exception of race, sex, marital status and melancholia, older patients differed from younger patients on all characteristics. Older patients had on average fewer lifetime depression spells and later age of onset and a higher proportion that had ever received ECT. A lower proportion of older patients had a comorbid diagnosis of generalized anxiety and older patients had more MMSE errors. Older adults also had more mobility limitations and more health conditions, but had higher levels of subjective social support and had experienced on average fewer life events the past year. The mean CES-D score was significantly lower for older patients. The patients had on average 7.8 DIS symptoms. The number of current DIS symptoms did not differ by age.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics at enrollment by age group (n=664)

| Sample Characteristic | Total Sample (n=664) | Adults 18-59 (n=366) | Adults 60 + (n=298) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (sd) | 54.1 (16.4) | 41.3 (9.1) | 69.9 (6.8) | t[657.4]=-45.99, p<0.0001 |

| No. White (%) | 610 (91.9%) | 330 (90.2%) | 280 (94.0%) | X2[1]=3.17, p=0.0751 |

| No. Female (%) | 433 (65.2%) | 247 (67.5%) | 186 (62.4%) | X2[1]=1.86, p=0.1725 |

| No. Married (%) | 404 (60.8%) | 230 (62.8%) | 174 (58.4%) | X2[1]=1.37, p=0.2424 |

| No. depression spells | ||||

| 0-3 | 272 (41.0%) | 129 (35.3%) | 143 (48.0%) | X2[2]=18.8, p<0.0001 |

| 4-10 or DK>1 | 242 (36.5%) | 133 (36.3%) | 109 (36.6%) | |

| 11+ | 150 (22.6%) | 104 (28.4%) | 46 (15.4%) | |

| Mean age of onset (sd) | 35.5 (18.7) | 26.4 (11.9) | 46.6 (19.4) | t [470.4]=-15.70, p<0.0001 |

| No. with mobility limitations (%) | 270 (40.7%) | 92 (25.1%) | 178 (59.7%) | X2[1]=81.48, p<0.0001 |

| Mean number MMSE errors (sd) | 2.1 (2.0) | 1.5 (1.7) | 2.8 (2.1) | t[544.0]=-9.19, p<0.0001 |

| No. with anxiety diagnosis (%) | 477 (71.8%) | 275 (75.1%) | 202 (67.8%) | X2[1]=4.39, p=0.0362 |

| Time depression worst | ||||

| No. No difference (%) | 272 (41.0%) | 147 (40.2%) | 125 (42.0%) | X2[2]=4.51, p=0.1050 |

| No. Worse in am (%) | 238 (35.8%) | 123 (33.6%) | 115 (38.6%) | |

| No. Worse in pm (%) | 154 (23.2%) | 96 (26.2%) | 58 (19.5%) | |

| Mean total stressful events past year (sd) | 2.7 (1.8) | 3.1 (2.1) | 2.2 (1.3) | t [632.3]=6.80, p<0.0001 |

| Mean total subjective social support (sd) | 24.7 (4.4) | 24.0 (4.5) | 25.5 (4.1) | t [662]=-4.63, p<0.0001 |

| No. ever received ECT (%) | 150 (22.6%) | 68 (18.6%) | 82 (27.5%) | X2[1]=7.50, p=0.0062 |

| Mean number of health conditions (natural log) (sd) | 1.9 (0.2) | 1.9 (0.2) | 2.0 (0.2) | t [479.2]=-8.65, p<0.0001 |

| Mean CES-D Total Score (sd) | 36.3 (13.6) | 38.0 (13.5) | 34.2 (13.5) | t[662]=3.66, p=0.0003 |

| Mean No. Current DIS Sx (sd) | 7.8 (3.6) | 7.9 (3.6) | 7.8 (3.5) | t[662]=0.25, p=0.8044 |

Table 2 shows the mean score for each CES-D symptom. Ten of the twenty symptoms had mean scores above 2.0, suggesting frequency and some level of severity as expected for patients with major depression. The interpersonal symptoms, people were unfriendly and people disliked me, were the symptoms with the lowest mean scores. Older patients had lower mean scores for bothered by things, thought life had been a failure, felt fearful, felt people were unfriendly, crying spells, felt sad, and felt others disliked them and had higher mean scores for poor appetite. Older patients were less likely to report enjoying life and feeling as good as others.

Table 2.

Mean CES-D item scores by age group at study enrollment (n=664)

| Symptom | Mean (sd) Total Sample | Mean (sd) ages 18-59 (n=366) | Mean (sd) ages 60 + (n=298) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Bothered by things that don't usually bother me | 1.82 (1.26) | 1.93 (1.21) | 1.68 (1.31) | t [662]=2.53, p=0.0116 |

| 2. Did not feel like eating; appetite was poor | 1.48 (1.31) | 1.34 (1.27) | 1.66 (1.33) | t [662]=-3.21, p=0.0014 |

| 3.Could not shake off the blues even with help from family/friends | 2.19 1.12) | 2.26 (1.06) | 2.11 (1.19) | t[599.9]=1.71, p=0.0871 |

| 4. Felt was just as good as other people (reverse coded) | 1.20 (1.32) | 1.49 (1.33) | 0.85 (1.22) | t[662]=6.42, p<0.0001 |

| 5. Trouble keeping mind on what doing | 2.21 (1.11) | 2.28 (1.07) | 2.13 (1.14) | t[662]=1.82, p=0.0692 |

| 6. Felt depressed | 2.47 (0.93) | 2.54 (0.87) | 2.39 (0.99) | t[596.5]=2.00, p=0.0464 |

| 7. Felt everything was an effort | 2.39 (1.00) | 2.39 (1.00) | 2.39 (1.01) | t [662]=-0.02, p=0.9869 |

| 8. Felt hopeful about the future (reverse coded) | 1.52 (1.24) | 1.60 (1.23) | 1.41 (1.26) | t[662]=2.04, p=0.0415 |

| 9. Thought life had been a failure | 1.46 (1.35) | 1.68 (1.35) | 1.19 (1.32) | t[662]=4.67, p<0.0001 |

| 10.Felt fearful | 1.92 (1.23) | 2.02 (1.20) | 1.81 (1.26) | t [662]=2.23, p=0.0260 |

| 11. Sleep was restless | 2.31 (1.04) | 2.32 (1.02) | 2.29 (1.07) | t[662]=0.42, p=0.6781 |

| 12. Was happy (reverse coded) | 2.19 (1.08) | 2.25 (1.01) | 2.12 (1.15) | t [597.2]=1.61, p=0.1081 |

| 13. Talked less than usual | 1.89 (1.26) | 1.90 (1.24) | 1.87 (1.28) | t[662]=0.37, p=0.7148 |

| 14. Felt lonely | 2.20 (1.13) | 2.24 (1.12) | 2.15 (1.14) | t [662]=1.08, p=0.2789 |

| 15. People were unfriendly | 0.55 (0.99) | 0.63 (1.03) | 0.45 (0.92) | t [656.2]=2.43, p=0.0153 |

| 16. Enjoyed life (reverse coded) | 2.04 (1.18) | 2.14 (1.09) | 1.92 (1.28) | t [585.5]=2.35, p=0.0190 |

| 17. Had crying spells | 1.15 (1.19) | 1.44 (1.18) | 0.79 (1.11) | t [662]=7.26, p<0.0001 |

| 18. Felt sad | 2.31 (1.05) | 2.44 (0.95) | 2.16 (1.15) | t [577.1]=3.36, p=0.0008 |

| 19. Felt people dislike me | 0.83 (1.19) | 0.98 (1.22) | 0.64 (1.12) | t [662]=3.64, p=0.0003 |

| 20. Could not get going | 2.14 (1.16) | 2.13 (1.13) | 2.16 (1.20) | t [662]=-0.29, p=0.7700 |

Table 3 shows the proportion endorsing each of the DIS symptoms. The most frequently reported symptoms were feeling sad, insomnia and having trouble concentrating. The symptoms reported the least often were attempting suicide, sleeping too much and gaining weight. Older patients were less likely to report gaining weight, feeling worthless, sinful or guilty, wanting to die and thinking about committing suicide. Older patients were more likely to endorse losing appetite, losing weight and losing interest in sex.

Table 3.

Percent reporting DIS symptom within two weeks prior to the interview by age group at enrollment (n=664)

| DIS Symptom | Total Sample | Ages 18-59 (n=366) | Ages 60 + (n=298) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Felt tired, sad, blue or depressed | 576 (86.8%) | 316 (86.3%) | 260 (87.3%) | X2[1]=0.12, p=0.7310 |

| Two years feeling depressed or sad | 328 (49.4%) | 193 (52.7%) | 135 (45.3%) | X2[1]=3.63, p=0.0568 |

| Lost your appetite | 211 (31.8%) | 98 (26.8%) | 113 (37.9%) | X2[1]=9.41, p=0.0022 |

| Lost weight without trying to | 131 (19.7%) | 46 (12.6%) | 85 (28.5%) | X2[1]=26.40, p<0.0001 |

| Gained weight | 47 (7.1%) | 38 (10.4%) | 9 (3.0%) | X2[1]=13.54, p=0.0002 |

| Trouble falling/staying asleep or waking up too early | 490 (73.8%) | 267 (73.0%) | 223 (74.8%) | X2[1]=0.30, p=0.5835 |

| Sleeping too much | 51 (7.7%) | 34 (9.3%) | 17 (5.7%) | X2[1]=2.98, p=0.0845 |

| Felt tired out all the time | 432 (65.1%) | 246 (67.2%) | 186 (62.4%) | X2[1]=1.66, p=0.1972 |

| Talked or moved more slowly than normal | 357 (53.8%) | 188 (51.4%) | 169 (56.7%) | X2[1]=1.89, p=0.1694 |

| Had to be moving all the time | 130 (19.6%) | 66 (18.0%) | 64 (21.5%) | X2[1]=1.24, p=0.2660 |

| Interest in sex lot less than usual | 433 (65.2%) | 215 (58.7%) | 218 (73.2%) | X2[1]=15.04, p=0.0001 |

| Felt worthless, sinful or guilty | 384 (57.8%) | 225 (61.5%) | 159 (53.4%) | X2[1]=4.44, p=0.0351 |

| Trouble concentrating | 479 (72.1%) | 264 (72.1%) | 215 (72.2%) | X2[1]=0.00, p=0.9962 |

| Thoughts came much slower or seemed mixed up | 407 (61.3%) | 228 (62.3%) | 179 (60.1%) | X2[1]=0.34, p=0.5577 |

| Thought a lot about death | 287 (43.2%) | 161 (44.0%) | 126 (42.3%) | X2[1]=0.20, p=0.6587 |

| Felt like you wanted to die | 185 (27.9%) | 114 (31.2%) | 71 (23.8%) | X2[1]=4.38, p=0.0363 |

| Thought about committing suicide | 237 (35.7%) | 156 (42.6%) | 81 (27.2%) | X2[1]=17.06, p<0.0001 |

| Attempted suicide | 32 (4.8%) | 21 (5.7%) | 11 (3.7%) | X2[1]=1.50, p=0.2207 |

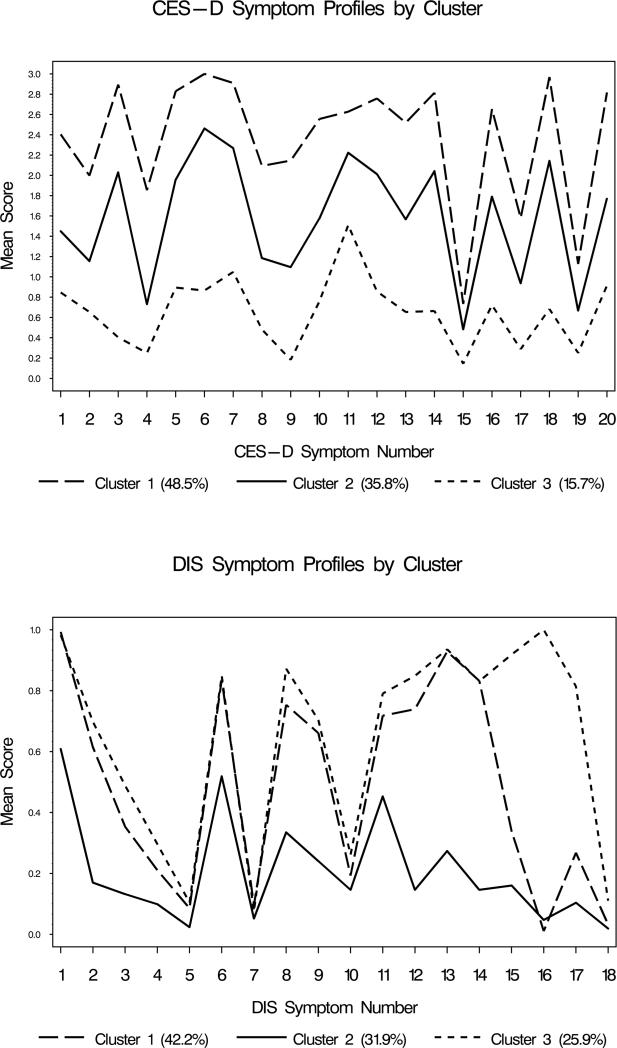

With the CES-D items as indicators, a three-cluster model best fit the data. Patients in Cluster 1 (48.5%) had the highest mean scores for all symptoms compared to the other two clusters, while those in Cluster 3 (15.7%) had the lowest mean symptom scores. The symptom profiles for the CES-D are shown in Figure 1. These clusters appear to differ primarily by severity.

Figure 1. Latent class symptom profiles based on endorsement of CES-D and DIS symptoms (n=664).

CES-D:1=Bothered by things; 2=Appetite poor; 3=Couldn't shake off blues; 4=Felt just as good as others (reverse coded); 5=Trouble concentrating; 6=Felt depressed; 7=felt everything effort; 8=Felt hopeful about future (reverse coded); 9=Thought life a failure; 10=Felt fearful; 11=Restless sleep; 12=Was happy (reverse coded); 13=Talked less than usual; 14=Felt lonely; 15=People were unfriendly; 16=Enjoyed life (reverse coded); 17=Crying spells; 18=Felt sad; 19=Felt people disliked me; 20=Could not get going;

DIS:1=Felt tired, sad, blue or depressed; 2=Two years feeling depressed or sad; 3=Lost appetite; 4=Lost weight without trying to; 5=Gained weight; 6=Trouble falling asleep, staying asleep or waking up too early; 7=Sleeping too much; 8=Felt tired out all the time; 9=Talked or moved more slowly than normal; 10=Had to be moving all the time; 11=Interest in sex lot less than usual; 12=Felt worthless, sinful or guilty; 13=Trouble concentrating; 14=Thoughts came much slower or seemed mixed up; 15=Thought a lot about death; 16=Felt like wanted to die; 17=Thought about committing suicide; 18=Attempted suicide;

With the DIS symptoms, a three-cluster model also best fit the data. As shown in Figure 1, the symptom profiles appear to show more heterogeneity than those observed in the CES-D. Patients in clusters did not appear to differ in their endorsement of weight gain, sleeping too much and moving all the time. For the other symptoms, patients in Cluster 2 (31.9%) generally had lower mean symptom scores on average compared to those in Cluster 1 (42.2%) and Cluster 3 (25.9%). Patients in Clusters 1 and 3 had similar mean scores for the symptoms with the exception of thinking a lot about death, wanting to die, and thinking about committing suicide. That is, the presence of suicidal thoughts appeared to differentiate Cluster 3 from Cluster 1.

In Table 4, we show the distribution of the sample characteristics by assigned cluster for the CES-D and the DIS. For both instruments, we observed differences by age, number of lifetime depression spells, comorbid diagnosis of generalized anxiety, and subjective social support. We observed differences across clusters identified through the CES-D but not the DIS by race and lifetime receipt of ECT. The clusters identified through the DIS differed by marital status and age of onset in addition to those in common with the CES-D.

Table 4.

Distribution of sample characteristics by cluster (n=664)

| CES-D | DIS | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Characteristic | Cluster 1 n=322 (48.5%) | Cluster 2 n=238 (35.8%) | Cluster 3 n=104 (15.7%) | Cluster 1 n=280 (42.2%) | Cluster 2 n=212 (31.9%) | Cluster 3 n=172 (25.9%) | ||

| Mean age (sd) | 52.6 (16.2) | 55.3 (17.0) | 56.3 (15.4) | F(2,661)=3.0, p=0.0483 | 55.2 (15.7) | 55.5 (16.4) | 50.7 (17.1) | F(2,661)=5.1, p=0.0065 |

| No. White (%) | 306 (95%) | 214 (90%) | 90 (87%) | X2[2]=9.5, p=0.0087 | 263 (94%) | 187 (88%) | 160 (93%) | X2[2]=5.7, p=0.0578 |

| No. Female (%) | 210 (65%) | 149 (63%) | 74 (71%) | X2[2]=2.3, p=0.3117 | 176 (63%) | 145 (68%) | 112 (65%) | X2[2]=1.6, p=0.4421 |

| No. Married (%) | 203 (63%) | 139 (58%) | 62 (60%) | X2[2]=1.3, p=0.5182 | 192 (69%) | 117 (55%) | 95 (55%) | X2[2]=12.1, p=0.0023 |

| No. depression spells | ||||||||

| 0-3 | 111 (34%) | 113 (48%) | 48 (46%) | X2[4]=13.2, p=0.0101 | 111 (40%) | 101 (48%) | 60 (35%) | X2[4]=12.8, p=0.0123 |

| 4-10 or DK>1 | 124 (38%) | 84 (35%) | 34 (33%) | 108 (38%) | 75 (35%) | 59 (34%) | ||

| 11+ | 87 (27%) | 41 (17%) | 22 (21%) | 61 (22%) | 36 (17%) | 53 (31%) | ||

| Mean age of onset (sd) | 34.0 (18.0) | 36.9 (19.9) | 36.7 (17.6) | F(2,661)=1.9, p=0.1567 | 36.1 (17.9) | 37.4 (19.5) | 32.0 (18.5) | F(2,661)=4.3, p=0.0143 |

| No. with mobility limitations (%) | 128 (40%) | 93 (39%) | 49 (47%) | X2[2]=2.2, p=0.3406 | 123 (44%) | 79 (37%) | 68 (40%) | X2[2]=2.3, p=0.3099 |

| Mean number MMSE errors (sd) | 2.1 (1.9) | 2.1 (2.1) | 1.9 (2.0) | F(2,661)=0.4, p=0.6594 | 2.1 (1.9) | 2.0 (2.1) | 2.1 (1.9) | F(2,661)=0.2, p=0.7978 |

| No. with anxiety diagnosis (%) | 260(81%) | 160 (67%) | 57 (55%) | X2[2]=30.0, p<0.0001 | 204 (73%) | 128 (60%) | 145 (84%) | X2[2]=27.1, p<0.0001 |

| Time depression worst | ||||||||

| No. No difference (%) | 136 (42%) | 85 (36%) | 51 (49%) | X2[4]=8.8, p=0.0654 | 117 (42%) | 81 (38%) | 74 (43%) | X2[4]=6.9, p=0.1398 |

| No. Worse in am (%) | 116 (36%) | 96 (40%) | 26 (25%) | 108 (38%) | 69 (33%) | 61 (35%) | ||

| No. Worse in pm (%) | 70 (22%) | 57 (24%) | 27 (26%) | 55 (20%) | 62 (29%) | 37 (22%) | ||

| Mean total stressful events past year (sd) | 2.8 (1.9) | 2.6 (1.8) | 2.5 (1.7) | F(2,661)=1.6, p=0.2091 | 2.6 (1.9) | 2.6 (1.8) | 2.9 (1.9) | F(2,661)=1.8, p=0.1741 |

| Mean total subjective social support (sd) | 23.5 (4.4) | 24.9 (4.4) | 27.7 (2.9) | F(2,661)=40.0, p<0.0001 | 24.7 (4.4) | 26.2 (3.8) | 22.7 (4.4) | F(2,661)=32.8, p<0.0001 |

| No. ever received ECT (%) | 96 (30%) | 35 (15%) | 19 (18%) | X2[2]=19.2, p<0.0001 | 70 (25%) | 36 (17%) | 44 (26%) | X2[2]=5.6, p=0.0601 |

| Mean number of health conditions (natural log) (sd) | 1.9 (0.2) | 1.9 (0.2) | 1.9 (0.2) | F(2,661)=1.2, p=0.3065 | 1.9 (0.2) | 1.9 (0.2) | 1.9 (0.2) | F(2,661)=0.3, p=0.7348 |

Table 5 presents the results of the multinomial logistic regression models. We first estimated models with demographic variables only. For the CES-D and DIS cluster models, age was a significant predictor of cluster membership when other demographic, health and social variables were controlled. For both measures, comorbid anxiety diagnosis and subjective social support differentiated the clusters and were the most significant predictors of cluster membership. For the CES-D, lifetime receipt of ECT differed across clusters, as did race and the presence of melancholic depression. The DIS derived clusters were differentiated by marital status in addition to anxiety and social support.

Table 5.

Odds ratios from multinomial logistic regression models predicting cluster membership (n=664)

| Clusters Based on CESD Symptoms | Clusters Based on DIS Symptoms | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster 2 v. Cluster 1 | Cluster 3 v. Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 v. Cluster 1 | Cluster 3 v. Cluster 1 | |||||||||

| Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | Wald Chi-Square | p-value | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | Wald Chi-Square | p-value | |

| Model 1 | ||||||||||||

| Age | *1.01 | 1.00, 1.02 | *1.02 | 1.00, 1.03 | 7.13 | P=0.0284 | 1.00 | 0.99, 1.01 | **0.98 | 0.97, 1.00 | 10.32 | P=0.0057 |

| White | *0.44 | 0.23, 0.84 | **0.33 | 0.15, 0.70 | 9.65 | P=0.0080 | *0.49 | 0.26, 0.95 | 0.93 | 0.43. 2.00 | 5.44 | P=0.0659 |

| Female | 0.88 | 0.62, 1.25 | 1.28 | 0.79, 2.08 | 2.16 | P=0.3402 | 1.24 | 0.85, 1.81 | 1.06 | 0.71, 1.58 | 1.22 | P=0.5443 |

| Model 2 | ||||||||||||

| Age | *1.02 | 1.00, 1.04 | *1.03 | 1.00, 1.05 | 7.49 | P=0.0237 | 1.01 | 0.99, 1.02 | *0.98 | 0.97, 1.00 | 6.62 | P=0.0365 |

| White | *0.39 | 0.19, 0.81 | *0.33 | 0.13, 0.80 | 8.16 | P=0.0169 | 0.51 | 0.25, 1.04 | 1.07 | 0.47, 2.44 | 4.63 | P=0.0990 |

| Female | 0.84 | 0.58, 1.23 | 1.13 | 0.65, 1.96 | 1.45 | P=0.4851 | 1.16 | 0.77, 1.75 | 1.03 | 0.68, 1.57 | 0.51 | P=0.7736 |

| Married | 0.77 | 0.53, 1.12 | 0.80 | 0.47, 1.38 | 2.00 | P=0.3678 | **0.53 | 0.35, 0.79 | *0.60 | 0.39, 0.91 | 11.41 | P=0.0033 |

| Lifetime Spells | ||||||||||||

| 11+ | *0.51 | 0.30, 0.86 | 0.69 | 0.33, 1.42 | 6.52 | P=0.1635 | 0.70 | 0.39, 1.24 | 1.37 | 0.78, 2.41 | 6.72 | P=0.1517 |

| 4-10 | 0.72 | 0.47, 1.11 | 0.78 | 0.42, 1.45 | 0.86 | 0.55, 1.36 | 0.85 | 0.52, 1.39 | ||||

| 0-3 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| Age of onset | 0.99 | 0.98, 1.01 | *0.98 | 0.96, 1.00 | 4.80 | P=0.0908 | 1.00 | 0.98, 1.01 | 1.00 | 0.99, 1.02 | 0.27 | P=0.8735 |

| Mobility limitations | 0.87 | 0.57, 1.32 | 1.12 | 0.63, 1.99 | 0.93 | P=0.6280 | *0.60 | 0.39, 0.94 | 0.87 | 0.55, 1.39 | 5.02 | P=0.0812 |

| Some cognitive impairment | 0.93 | 0.84, 1.03 | 0.90 | 0.78, 1.04 | 2.79 | P=0.2480 | 0.96 | 0.86, 1.07 | 1.03 | 0.92, 1.15 | 1.15 | P=0.5632 |

| Anxiety diagnosis | **0.51 | 0.34, 0.77 | ***0.35 | 0.21, 0.60 | 17.53 | P=0.0002 | *0.63 | 0.42, 0.95 | *1.81 | 1.09, 3.00 | 15.57 | P=0.0004 |

| Depression | ||||||||||||

| Worse in am | 1.29 | 0.81, 2.06 | 1.10 | 0.59, 2.06 | 10.20 | P=0.0372 | **1.75 | 1.08, 2.85 | 0.97 | 0.57, 1.64 | 8.83 | P=0.0656 |

| Worse in pm | 1.27 | 0.84, 1.93 | *0.51 | 0.28, 0.93 | 0.89 | 0.57, 1.39 | 0.93 | 0.59, 1.46 | ||||

| No difference | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| Stressful events past yr | 1.01 | 0.91, 1.12 | 1.03 | 0.89, 1.20 | 0.18 | P=0.9149 | 1.02 | 0.91, 1.14 | 0.98 | 0.87, 1.09 | 0.47 | P=0.7908 |

| Subjective social support | **1.06 | 1.02, 1.11 | ****1.35 | 1.24, 1.47 | 51.15 | P<0.0001 | ****1.11 | 1.05, 1.17 | **0.93 | 0.89, 0.98 | 37.15 | P<0.0001 |

| Lifetime ECT | ****0.37 | 0.24, 0.59 | **0.43 | 0.23, 0.81 | 20.17 | P<0.0001 | 0.65 | 0.40, 1.05 | 1.17 | 0.74, 1.86 | 4.89 | P=0.0869 |

| Health conditions (natural log) | 1.01 | 0.37, 2.74 | 1.48 | 0.38, 5.84 | 0.36 | P=0.8347 | 1.51 | 0.52, 4.43 | 2.45 | 0.83, 7.21 | 2.68 | P=0.2620 |

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

p<0.0001

It is important to note that patients were assigned to the cluster where they had the highest probability of membership. The separation of clusters appears to be sound for both measures. For the clusters defined from the CES-D, the average probability of membership for Cluster 1 was 0.96 (range 0.51-0.99), for Cluster 2 was 0.92 (range 0.51-0.99) and for Cluster 3 was 0.94 (range 0.52-1.00). For the DIS defined clusters the average probability of membership for Cluster 1 was 0.92 (range 0.51-0.99), for Cluster 2 was 0.94 (range 0.50-0.99) and for Cluster 3 was 0.97 (range 0.58-0.99).

Discussion

We report age differences in symptom expression between primarily middle-aged and older patients diagnosed with major depression, confirming our first hypothesis. Our preliminary analyses of these differences in two qualitatively different measures as well as age differences in potential exposures within a mixed age sample provides new information to the field. While age differences in symptoms such as sadness are known, age differences in symptoms such as life satisfaction, crying spells and feeling disliked by others have not previously been reported. We observed age differences in the sadness question in the CES-D but not in the lead question of the DIS asking if the patient felt tired, sad or blue. Like the instruments, these two questions may be qualitatively different. Older adults with major depression were more likely than middle-aged adults to endorse loss of interest in sex within the previous two weeks. Age differences for this symptom, however, were not significant when we included only symptoms that met DIS criteria (code 5). These findings support discussion that the nomenclature may be less applicable to older adults who may not experience the depressive symptom for the required two weeks or with the required severity (Blazer, 1994).

Our second hypothesis, that we would find heterogeneity in symptom expression within a mixed age sample of patients with major depression, was confirmed. Using two measures of depressive symptoms, three-cluster models best fit the data. While in the CES-D the symptom profiles differed primarily by severity, there was considerable heterogeneity in symptom expression when the DIS symptoms, symptoms assessed in a typical clinical interview, were used as the model indicators. It is important to note the CES-D and the DIS are used for different purposes and we would not expect the profiles to mirror each other. While the two instruments cannot be directly compared and a comparative approach was not the focus of the study, the two measures do provide different perspectives regarding the phenomenology of depression.

Another component of the second hypothesis, that the clusters would differ by age of the patients as well as other potential risk factors, was modestly supported. In the clusters derived from the CES-D, the younger patients had higher symptom scores across all symptoms on average. In the DIS derived clusters we observed that younger/middle-aged patients were more likely to endorse thoughts of death and suicide than older patients. We also noted potential exposures were differentially distributed across the clusters derived from both measures.

There is surprisingly little information available concerning age differences in symptom expression among patients with major depression. Our symptom comparisons are particularly informative. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time LCA has been applied to a mixed age sample of patients with major depression. While we found age differences, we did not identify a symptom profile unique to late life depression that included, for example, more somatic symptoms and/or less sadness. That is, we did not identify age-specific clusters. The presence of anxiety and level of social support appeared to be the strongest predictors of heterogeneity, and comorbid anxiety was only weakly associated with age.

While others have reported gender differences in symptom profiles (Brodaty et al., 2005; Christensen et al., 1999), we did not find gender differentiated the clusters in this sample of adults with major depression. In uncontrolled analyses, we found differences in age of onset across the clusters identified from the DIS symptoms, with the cluster associated with middle-aged/younger patients having an earlier age of onset, consistent with earlier reports (Kessler et al., 2010). We did not find significant differences in age of onset across clusters, however, when potential confounders were included in the analysis.

Our study has several limitations. Our sample was predominantly White and generally healthy. In addition, older patients with dementia were excluded from these analyses. Our sample, therefore, may not be representative of all patients with major depression, particularly older patients. We believe our sample is representative of patients typically seen in clinical practice. That is, patients typically have a history of multiple episodes of major depression, many have received ECT, and older patients often have a later age of onset. These experiences may play a role in symptom expression. LCA assigns participants to clusters based on probability and is not without classification error. Although we relied on statistical criteria to assess model fit, there is still subjectivity involved. These analyses are primarily descriptive and hypothesis generating. We did compare groups, however, and cannot rule out a Type I error.

In summary, these findings provide new information. In measures routinely administered in clinical and research settings there were age differences in symptom expression between middle-aged and older patients with major depression. These analyses utilized state of the art statistical techniques to address important clinical questions about age differences in the structure of major depression. While heterogeneity has been established in mixed age community samples and among older adults in clinical samples, sources of heterogeneity have not been reported in mixed age samples with one categorical diagnosis of major depression. We report discrete clusters of patients within a group with one diagnosis that are differentiated, in part, by age. These findings confirm that late life depression remains complex. Whereas symptoms may not be as severe or reported as often in older adults, the symptom profiles were essentially similar to those observed among younger/middle-aged adults. Future work could address whether there are developmental or biological variables related to age that may contribute to cluster separation.

Key Points.

Older patients with major depression endorse different symptoms than younger/middle-aged patients, but there does not appear to be a symptom profile unique to late life depression.

Older patients were more likely to endorse poor appetite and loss of interest in sex but were less likely to endorse sadness, crying spells, feeling fearful or bothered or that life was a failure, enjoying life, feeling as good as others, feeling worthless and suicidal thoughts.

Compared to younger/middle-aged patients, older patients with major depression had later age of onset, had fewer lifetime spells, were more likely to have received ECT, had more cognitive impairment, health conditions and functional limitations, and were less likely to have comorbid anxiety.

Acknowledgements

The analysis and preparation of this manuscript were supported by NIMH grant R01 MH 080311 (Hybels).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors report no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Celia F. Hybels, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences Center for the Study of Aging and Human Development Duke University Medical Center Box 3003 Durham NC 27710 cfh@geri.duke.edu Phone: (919) 660-7546 FAX: (919) 668-0453.

Lawrence R. Landerman, Department of Medicine Center for the Study of Aging and Human Development Duke University Medical Center.

Dan G. Blazer, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences Center for the Study of Aging and Human Development Duke University Medical Center.

References

- Alexopoulos G, Meyers B, Young R, Campbell S, Silbersweig D, Charlson M. ‘Vascular depression’ hypothesis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997a;54:915–922. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830220033006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexopoulos GS, Meyers BS, Young RC, Kakuma T, Silbersweig D, Charlson M. Clinically defined vascular depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1997b;154:562–565. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.4.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . DSM-III: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Third ed. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Berry JM, Storandt M, Coyle A. Age and sex differences in somatic complaints associated with depression. J Gerontol. 1984;39:465–467. doi: 10.1093/geronj/39.4.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazer DG. Is depression more frequent in late life? An honest look at the evidence. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1994;2:193–199. doi: 10.1097/00019442-199400230-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazer DG, Bachar JR, Hughes DC. Major depression with melancholia: A comparison of middle-aged and elderly adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1987;35:927–932. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1987.tb02294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazer DG, Hybels CF. Origins of depression in later life. Psychol Med. 2005;35:1241–1252. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705004411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodaty H, Cullen B, Thompson C, Mitchell P, Parker G, Wilhelm K, Austin M, Malhi G. Age and gender in the phenomenology of depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13:589–596. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.7.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodaty H, Luscombe G, Parker G, Wilhelm K, Hickie I, Austin MP, Mitchell P. Increased rate of psychosis and psychomotor change in depression with age. Psychol Med. 1997;27:1205–1213. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797005436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodaty H, Peters K, Boyce P, Hickie I, Parker G, Mitchell P, Wilhelm K. Age and depression. J Affect Disord. 1991;23:137–149. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(91)90026-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce ML. Psychosocial risk factors for depressive disorders in late life. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52:175–184. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01410-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen H, Jorm AF, MacKinnon AJ, Korten AE, Jacomb PA, Henderson AS, Rodgers B. Age differences in depression and anxiety symptoms: a structural equation modelling analysis of data from a general population sample. Psychol Med. 1999;29:325–339. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798008150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton WW, Dryman A, Sorenson A, McCutcheon A. DSM-III major depressive disorder in the community: A latent class analysis of data from the NIMH Epidemiologic Catchment Area Programme. Br J Psychiatry. 1989;155:48–54. doi: 10.1192/bjp.155.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh P. Mini-mental state: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for clinicians. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo JJ, Anthony JC, Muthen BO. Age differences in the symptoms of depression: A latent trait analysis. J Gerontol Psychol Sci. 1994;49:P251–P264. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.6.p251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo JJ, Rabins PV, Lyketsos CG, Tien AY, Anthony JC. Depression without sadness: Functional outcomes of nondysphoric depression in later life. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45:570–578. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb03089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatz M, Hurwicz M. Are old people more depressed? Cross-sectional data on Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale factors. Psychol Aging. 1990;5:284–290. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.5.2.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hybels CF, Blazer DG, Landerman LR, Steffens DC. Heterogeneity in symptom profiles among older adults diagnosed with major depression. Int Psychogeriatr. 2011 doi: 10.1017/S1041610210002346. First published online 18 January 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hybels CF, Blazer DG, Pieper CF, Landerman LR, Steffens DC. Profiles of depressive symptoms in older adults diagnosed with major depression: Latent cluster analysis. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17:387–396. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31819431ff. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorm AF, Windsor TD, Dear KBG, Anstey KJ, Christensen H, Rodgers B. Age group differences in psychological distress: the role of psychosocial risk factors that vary with age. Psychol Med. 2005;35:1253–1263. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705004976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Birnbaum H, Bromet E, Hwang I, Sampson N, Shahly V. Age differences in major depression: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). Psychol Med. 2010;40:225–237. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709990213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC. DSM categories and dimensions in clinical and research contexts. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2007;16(S1):S8–S15. doi: 10.1002/mpr.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landerman R, George LK, Campbell RT, Blazer DG. Alternative models of the stress buffering hypothesis. Am J Community Psychol. 1989;17:625–641. doi: 10.1007/BF00922639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln KD, Chatters LM, Taylor RJ, Jackson JS. Profiles of depressive symptoms among African Americans and Caribbean Blacks. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65:200–213. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.02.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magidson J, Vermunt JK. Latent class models for clustering: A comparison with K-means. Canadian Journal of Marketing Research. 2002;20:37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Musetti L, Perugi G, Soriani A, Rossi VM, Cassano GB, Akiskal HS. Depression before and after age 65. A re-examination. Br J Psychiatry. 1989;155:330–336. doi: 10.1192/bjp.155.3.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Helzer JE, Croughan J, Ratcliff K. National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule: Its history, characteristics, and validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1981;38:381–389. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1981.01780290015001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute . Statistical Analysis System, Version 9.2. SAS Institute; Cary NC: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan PF, Kessler RC, Kendler KS. Latent class analysis of lifetime depressive symptoms in the National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:1398–1406. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.10.1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan PF, Prescott CA, Kendler KS. The subtypes of major depression in a twin registry. J Affect Disord. 2002;68:273–284. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00364-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermunt J, Magidson J. Latent class cluster analysis. . In: Hagenuars J, McCutcheon A, editors. Applied Latent Class Analysis. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2002. pp. 89–106. [Google Scholar]

- Vermunt J, Magidson J. Latent GOLD 4.0 User's Guide. Statistical Innovations, Inc.; Belmont, Massachusetts: 2005. [Google Scholar]