Abstract

BACKGROUND

Xenotropic murine leukemia virus–related retrovirus (XMRV) is a recently discovered gammaretrovirus that was originally detected in prostate tumors. However, a causal relatioship between XMRV and prostate cancer remains controversial due to conflicting reports on its etiologic occurrence. Even though gammaretroviruses are known to induce cancer in animals, a mechanism for XMRV-induced carcinogenesis remains unknown. Several mechanisms including insertional mutagenesis, proinflammatory effects, oncogenic viral proteins, immune suppression and altered epithelial/stromal interactions have been proposed for a role of XMRV in prostate cancer. However, biochemical data supporting any of these mechanisms are lacking. Therefore, our aim was to evaluate a potential role of XMRV in prostate carcinogenesis.

METHODS

Growth kinetics of prostate cancer cells are conducted by MTT assay. In vitro transformation and invasion was carried out by soft agar colony formation, and Matrigel cell invasion assay, respectively. p27Kip1 expression was determined by western blot and MMP activation was evaluated by gelatin-zymography. Up-regulation of miR221 and miR222 expression was examined by real-time PCR.

RESULTS

We demonstrate that XMRV infection can accelerate cellular proliferation, enhance transformation and increase invasiveness of slow growing prostate cancer cells. The molecular basis of these viral induced activities is mediated by the downregulation of cyclin/cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor p27Kip1. Downstream analyses illustrated that XMRV infection upregulates miR221 and miR222 expression that target p27Kip1 mRNA.

CONCLUSIONS

We propose that downregulation of p27Kip1 by XMRV infection facilitates transition of G1 to S, thereby accelerates growth of prostate cancer cells. Our findings implicate that if XMRV is present in humans, then under appropriate cellular microenvironment it may serve as a cofactor to promote cancer progression in the prostate.

INTRODUCTION

Xenotropic murine leukemia-related retrovirus (XMRV) was first detected in nonmalignant stromal cells in a subset of patients with prostate cancer using viral detection DNA microarray (1). Subsequently, XMRV proteins were detected in malignant epithelial cells but not in the stromal cells of high grade prostate tumor (2). In addition, the presence of XMRV in patients with prostate cancer was also reported by using a serum-based assay for neutralising antibodies against XMRV, PCR and fluorescence in situ hybridisation (FISH) (3). Integrated copies of XMRV were also detected in prostatic cancer cell line of epithelial origin (4). However, a role of XMRV in prostate cancer remains highly controversial since several groups have failed to detect the virus in prostate tissues (5–8). These discrepancies have been attributed to several factors including a) methods used for XMRV detection, b) selection geographic distribution of human specimens, and c) possible contamination of mouse DNA (9–11). Currently there is no general consensus on the origin and prevalence of XMRV in the human population. Therefore, whether XMRV is a genuine human pathogen remains highly controversial. A comparative analysis of XMRV sequences from patients and cell-cultures shows one monophyletic cluster (5). This has raised the question whether the XMRV strains found in patients are derived from the laboratory. A recent report by Paprotka et al. suggests that XMRV may have been originated in the laboratory by a rare recombination event between two mice proviruses (12). These authors also speculate that the association of XMRV with human diseases is due to contamination of samples with virus. Given that these authors relied only on PCR analysis, further studies are warranted to confirm whether the recombination occurred during or prior to xenograft. Intriguingly, very recent data presented in the 2011 Cold Spring Harbor Retroviral meeting suggest the presence of XMRV in the androgen secreting Leydig cells of testis in large percentage of US men (13). Furthermore, an animal study using a macaque model also demonstrates the ability of XMRV to infect various organs including the prostate (14).

Despite the controversies, there is a consensus that XMRV is a genuine retrovirus and is the first gammaretrovirus that has the potential to infect humans. XMRV shares a 94% overall sequence similarity with known endogenous and exogenous murine leukemia viruses (MLVs) (9). However, XMRV harbors distinct amino acid substitutions and a short deletion in the gag leader region (1). Since gammaretroviruses lack host-derived oncogenes several plausible mechanisms have been proposed for XMRV-induced carcinogenesis. One possibility is that XMRV Env has oncogenic property, since other retroviral Env proteins have oncogenic activity (15–16). In addition, integration of the proviral DNA in the host genome may regulate expression of cellular genes that are important for cancer (17). However, data from prostate tumors suggest that not all tumor cells are infected with XMRV (1, 9), indicating involvement of other cellular processes for tumorigenesis. Metzger et al. have proposed that XMRV lacks direct transforming activity although it induced rare transformed foci in rat fibroblasts (18). Other plausible mechanisms for XMRV induced oncogenesis include proinflammatory effects, immune suppression and altered epithelial/stromal interactions (9). Unfortunately, due to lack of data the mechanism of XMRV-induced carcinogenesis remains unclear. Given that gammaretroviruses cause cancer in animals, understanding the molecular details of XMRV infection in human prostate cancer cells will shed light on its potential contribution to human disease.

XMRV infects and efficiently replicates in prostate cancer cell lines (19). As an in vitro model of distinct stages of prostate carcinoma progression, we used the “slow growing” androgen-dependent LNCaP cell line (20) and the “aggressive” androgen-independent PC-3 cell line (21). We demonstrate that XMRV infection accelerates cellular proliferation of LNCaP cells but not that of PC-3 cells. Our data also reveal that viral infection increases transforming activity and enhances invasiveness prostate cancer cells. Deregulation of cell cycle control proteins plays a central role in cell division and development of cancer. In eukaryotic cells, cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) together with their regulatory subunits “cyclins” regulate cell-cycle progression (22). p27Kip1 is a member of a family of CDK inhibitors that bind to cyclin/CDK complexes and arrest cell cycle (22). Therefore, p27Kip1 plays an important role in cell proliferation, cell differentiation, and apoptosis (23–24). Targeted disruption of p27Kip1 gene results in hyperplasia of multiple tissues including the prostate, demonstrating its functional role in prostate carcinogenesis (25–26). Furthermore, p27Kip1 is a putative tumor-suppressor gene and its absence or decreased expression is associated with high grade prostate tumors (27–28). Our data revealed that XMRV infection downregulates p27Kip1 expression via upregulation of miR-221 and miR-222 expression that target p27Kip1 mRNA. In addition, XMRV infection resulted in an upregulation of the zymogen activity of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) that are critical for degradation of extracellular matrix during invasion (29–30). Our data also indicate that these virally induced molecular alterations are partly dependent on androgen. Since cancer progression requires tumor cells to grow invasively and migrate through multiple tissue barriers, our data demonstrate that XMRV may serve as a co-factor for prostate cancer progression.

MATERIALS & METHODS

Cell Lines and Viral Infection

All cell lines were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 20 mM L-glutamine, 100 units/ml of penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin sulfate in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 at 37°C. LNCaP and DU145 cells were purchased from ATCC. XMRV infects and replicates in LNCaP cells efficiently (17). Once infected, LNCaP cells produce XMRV continuously. We use chronically infected LNCaP cells with XMRV (a gift from Dr. James Hildreth, Meharry Medical College) as the source of XMRV and chronically infected 293T cells with ampho-MLV (a gift from Dr. Alan Rein, NCI) as the source of ampho-MLV. We collect the culture supernatant every 24 hrs and filter it through a 0.2-μm filter and store at −80°C. We use this culture supernatant as the source of infectious XMRV for our infection experiments. Prior to infection this culture supernatant is thawed at 37°C water bath. Virus infections were performed using cells plated 1 day before infection. Cells were at 50% confluency at the time of infection. On the day of infection, fresh media containing 5 μg/ml polybrene was added to the cells and virus was layered on the cells and incubated for 6 h to allow virus adsorption. Cells were then washed once with PBS, and fresh media containing FBS were added.

MTT cell proliferation assay

Vybrant MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) Cell Proliferation Assay Kit was purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA) and assay was performed in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, 5×104 cells/well were seeded in a 24-well plate and the proliferation was then measured at OD570 nm at different time intervals. Three independent experiments were performed in triplicates.

Flow Cytometry

G1/S cell cycle transition was evaluated by propidium iodide staining, a widely used method for cell cycle analysis. Cells were harvested and washed with PBS, and fixed with 70% ethanol. These cells were treated with 500 μg/mL RNase for 5 min and stained with 50 μg/mL propidium iodide for 45 min at room temperature in the dark. Subsequently, DNA content was analyzed in these samples by flow cytometry (BD Biosciences). Three independent experiments were performed in triplicates.

Soft Agar Colony Assay

Anchorage-independent growth was determined by soft agar analysis using the cell transformation detection assay kit (Millipore), following the instructions of the manufacturer. Briefly, 2×103 LNCaP cells infected with/without XMRV were seeded in 12-well culture dishes in RPMI with 0.4% agar on top of a base layer containing 0.8% agar. Cells were fed with growth media (100–200 μl/well) once a week until colonies grew to a suitable size for observation (approximately 2–3 weeks). Colonies were stained overnight at 37°C and counted under a microscopic field at ×10 magnification. Each assay was performed in triplicates on three independent occasions.

In vitro Matrigel Invasion Assay

Matrigel invasion assay was performed using a 24-well invasion chamber system (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA) with Matrigel membrane (8.0-μm pore). Briefly, in each well 500 μl of FBS as the chemo-attractant was placed in the lower compartment of the chamber. In the pre-warmed and rehydrated upper compartment, 5×104 cells in 500 μl of RPMI1640 medium without FBS were added. These cells were allowed to migrate through the intermediate membrane for 24h at 37°C. After 24 h the cells at the upper surface of the filters were wiped away with a cotton swab, and the filters were fixed and stained using the Hemacolor staining kit (EMD). The filters were removed from the invasion chamber using a scalpel blade and mounted onto glass microscope slides. The cells attached to the lower side of the membrane were counted in 10 high-powered (×200) fields under a microscope. Assays were done in triplicates for each experiment, and each experiment was repeated three times.

Western Blot Analysis

Cell lysates were prepared and quantified according to established methods. Equal amounts of cell lysates were electrophoresed on 4–12% SDS–polyacrylamide gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane using a semi-dry blotter (Bio-Rad). Membranes were blocked using Tris-buffered saline with 5% nonfat milk (pH 8.0; Sigma). Blots were then probed with the appropriate primary antibody in blocking buffer overnight at 4°C. Incubation with secondary anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (1:2000) was performed at room temperature for 1 h. All blots were washed in Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 (pH 8.0; Sigma) and developed using the enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) procedure (Amersham, Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). Blots were routinely stripped by Encore Blot Stripping Kit (Novus Molecular, Inc., San Diego, CA) and reprobed with anti-actin monoclonal antibody (Sigma) (1:2000) to serve as loading controls. For detecting XMRV we use goat polyclonal anti-Rauscher MLV p30 Gag (a gift from Dr. Sandra Ruscetti, NCI-Frederick) that reacts with XMRV p30 and its precursor Gag.

Determination of MMP Activation by Gelatin Zymography

Cells infected with/without XMRV were grown in serum-free medium for 24 h. The medium was concentrated using 10 kDa Amicon Ultra-4 spin columns and equal protein loads were used for zymography. Gelatinase zymography was performed in 10% Novex pre-cast polyacrylamide gel (Invitrogen) in the presence of 0.1% gelatin under non-reducing conditions. After electrophoresis, the gel was washed 5 times in zymogram wash buffer followed by three washes in incubation buffer and then incubated for 24 h at 37°C in incubation buffer before being stained with coomassie blue (G-250) for visualization of activation. After destaining (30% methanol, 1% formic acid), MMP-2 and MMP-9 activities were visualized as two clear bands against a blue background. Molecular markers were used to identify MMP2/9. Protein standards were run concurrently and approximate molecular weights were determined.

RNA Extraction and PCR Analysis

Total RNA was extracted cells with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RT PCR was carried out using Ready-To-Go RT PCR beads from GE Health care as per the user guidelines. Random hexamer was used for cDNA synthesis and for subsequent amplification amplicon specific primers were used. (PCR cycle conditions: 37°C for 1 hr, 95°C for 5 min, 30 cycles of 95°C for 30 sec, 55°C for 30 Sec and 72°C for 1 min and Final Extension at 72°C for 3 min). For quantitative real time PCR, first strand cDNA was synthesized using miRNA specific LNA primers and universal cDNA synthesis kit (Exiqon). Quantitative PCR was carried out using MyiQ2 Real Time PCR machine (Bio-Rad) and the 2X SYBRR® Green Master mix from Exiqon. Samples were run in triplicates, and relative expression levels were determined compared with 5S rRNA expression. (PCR cycle conditions: 95°C for 10 min, 45 cycles of 95°C for 10 sec, and 60°C for 1 min).

RESULTS

XMRV Infection Accelerates Proliferation of “Slow Growing” Prostate Cancer Cells

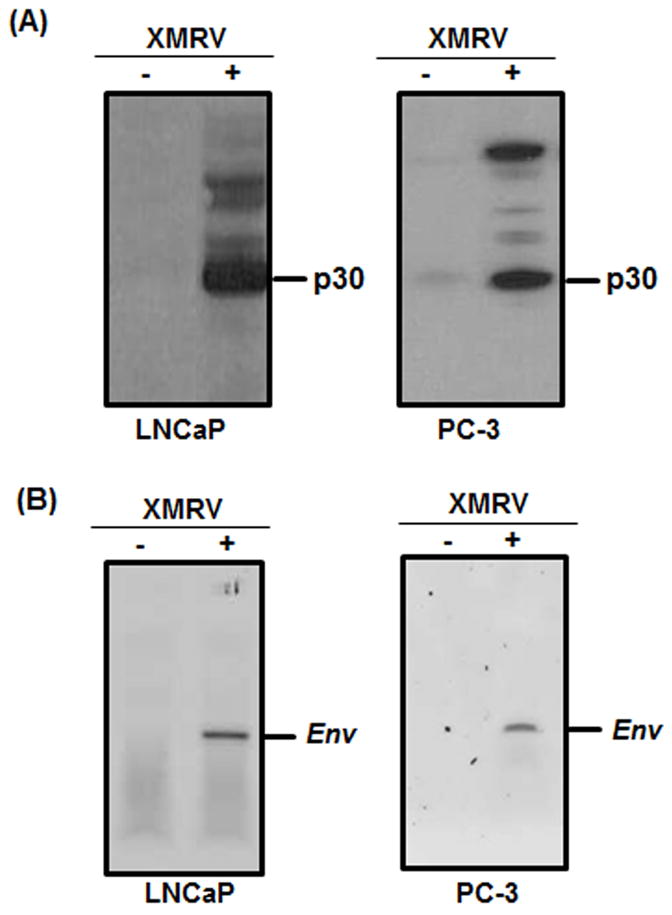

Since XMRV was detected in aggressive prostate tumors, we evaluated whether XMRV infection affects proliferation of prostate cancer cells. We used LNCaP and PC-3 cells to mimic different stages of prostate cancer progression. Infection of these cells with XMRV was confirmed by western blot and RT-PCR analysis. We detected XMRV p30 protein in the XMRV infected cells but not in the uninfected cells (Fig 1A). Since laboratory contamination of XMRV DNA has been reported recently in RT-PCR kits (10–11, 31), we carried out RT-PCR analysis and amplified XMRV Env amplicon only in the infected cells negating contamination problems (Fig 1B).

Fig. 1. XMRV infection analysis.

(A) Western blot analysis of cell lysates from uninfected (−) and XMRV infected (+) cells. We detected XMRV p30 protein by using goat polyclonal anti-Rauscher MLV p30 Gag. The XMRV p30 capsid was detected in the infected cells but not in the uninfected cells. (B) RT-PCR analysis of RNA isolated from uninfected (−) and XMRV infected (+) LNCaP cells using XMRV Env specific primers. The Env amplicon was detected in the XMRV infected cells but not in the uninfected cells. The RT-PCR assay was conducted to exclude possible contamination of mouse DNA in our experiments.

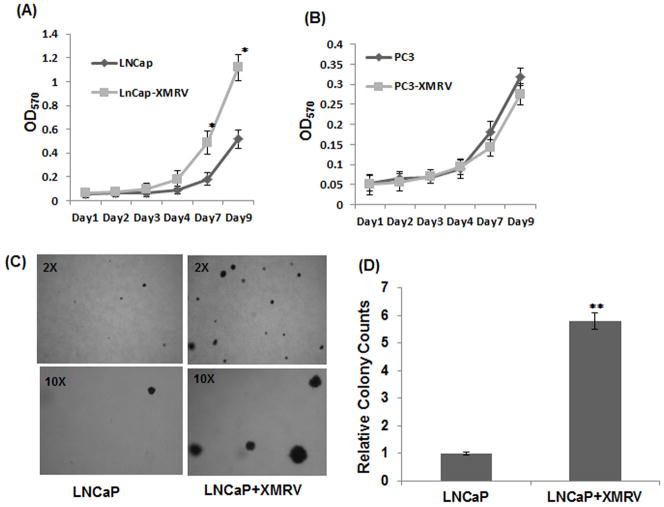

Subsequently, we evaluated XMRV induced cellular proliferation by seeding 5×104 cells in 24-well plate and carrying out MTT assay at different time intervals. A comparative analysis revealed that XMRV infected LNCaP cells grew significantly faster than the uninfected cells (Fig. 2A). By day nine, infected LNCaP cells started to outgrow uninfected cells by almost two fold. In contrast, the proliferation of PC-3 cells was minimally altered by XMRV infection (Fig. 2B). These data emphasized that XMRV infection accelerated proliferation of the slow growing prostate cancer cells but not the growth of aggressive cells.

Fig. 2. Effect of XMRV infection on proliferation and colony forming ability of prostate cancer cells.

(A–B) Cellular proliferation was determined by MTT assay by measuring the OD570 nm. 5×104 cells per well were seeded in a 24-well plate and proliferation was then measured at different time intervals. (A) The virally infected LNCaP cells outgrew the uninfected cells by day nine. Data presented are mean value of three independent experiments that are performed in triplicates. The results are expressed as mean ± S.E. for three separate experiments. * p < 0.01 is for XMRV-infected cells compared with uninfected cells. (B) XMRV infection in PC-3 cells have minimal or no effect on cellular proliferation. (C–D) Colony formation was determined by soft agar assay by seeding 2×104 cells in 12-well culture dishes and feeding with growth media once a week for 2–3 weeks. Colonies were stained overnight at 37°C overnight and counted under microscope. (C) Representative frames depicting number and size of colonies in uninfected and XMRV infected LNCaP cells. The insets in each panel represent the magnification at which the frames were visualized. (D) Comparative analysis of relative number of colonies formed by uninfected and infected cells. Data represents average colony counts from three independent experiments with triplicates for each sample. * p < 0.005 is for XMRV-infected cells compared with uninfected cells.

XMRV Infection Enhances the Transformational Activity of LNCaP Cells

Cellular transformation, a characteristic of tumorigenic cancer cells, is the ability of tumor cells to grow in an anchorage independent manner in a semisolid medium. LNCaP being a transformed cell line forms colonies in soft agar media. To assess whether XMRV infection affects the transforming activity of LNCaP cells, we carried out soft agar assay. We performed a standard transformation assay by seeding 2×103 cells in 12-well culture dishes in 0.4% agar on top of a base layer containing 0.8% agar. After 2–3 weeks colonies were counted after staining overnight at 37°C and the results are presented in Fig. 2 (C–D). As expected uninfected cells formed colonies in soft agar since they are transformed (Fig. 2C). However, the average colony counts of XMRV infected cells were almost 5–6 times higher than the uninfected cells (Fig. 2D). In addition, the dimensions of the colonies formed by the infected cells were substantially larger than the colonies from uninfected cells (Fig. 2C). These results demonstrated that XMRV has the ability to enhance the clonogenicity and size of colonies formed by LNCaP cells.

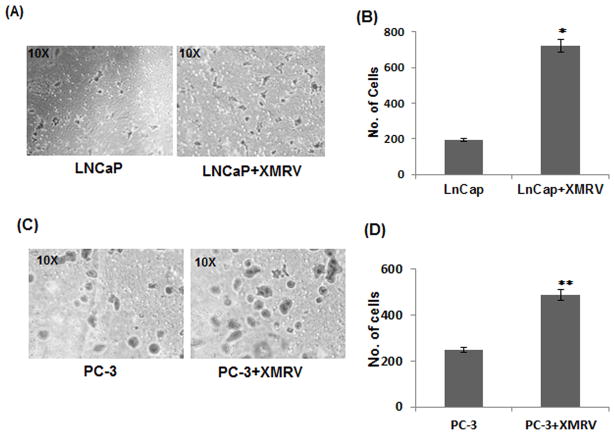

Invasiveness of Prostate Cancer Cells is Accelerated by XMRV Infection

Being metastatic in nature, LNCaP and PC-3 cells have the ability to invade through the subendothelial matrix (19). We examined the effect of XMRV infection on the invasiveness of these cells by carrying out Matrigel invasion assay. We used dual chambered invasion plates containing reconstituted extracellular matrices overlaid on 8 μM pore sized membrane in our experiments. The invasive nature of the cells was measured by their spontaneous ability to migrate from the upper chamber to the lower chamber of the invasion plate. We seeded 5×104 cells in the upper chamber in serum free media and added serum in the lower chamber as a chemo-attractant. After 24 hrs, the cells in the lower chamber were fixed, stained and counted under microscope. It is evident from Fig. 3 that the number of infected cells invaded through the membrane is significantly higher than the uninfected cells. A comparative analysis indicated that XMRV infection enhanced the invasiveness of LNCaP cells almost 3.5 fold (Fig. 3B), whereas that of PC-3 cells at 2.5 fold (Fig. 3D). These results emphasized that XMRV has the ability to increase the invasiveness of both slow-growing and aggressive prostate cancer cells.

Fig. 3. XMRV infection increases the invasiveness of prostate cancer cells.

Cell invasion properties of uninfected and infected cells were determined by Matrigel invasion assay. 5×104 cells in were seeded in the upper chamber of a 24-well invasion chamber system. Using serum as the chemo-attractant in the lower compartment, invasion was measured by the ability of cells to migrate through the intermediate membrane. Assays were performed in triplicates with each experiment repeated three times. Invasion assay of LNCaP (A–B) and PC-3 (C–D) cells. (A and C) Representative frames showing number of cells invaded through the membrane barrier. (B and D) Comparative analysis of relative cell numbers that invaded through the membrane. The results are expressed as mean ± S.E. for three separate experiments. * p < 0.001 and ** p < 0.001 are for XMRV-infected cells compared with uninfected cells.

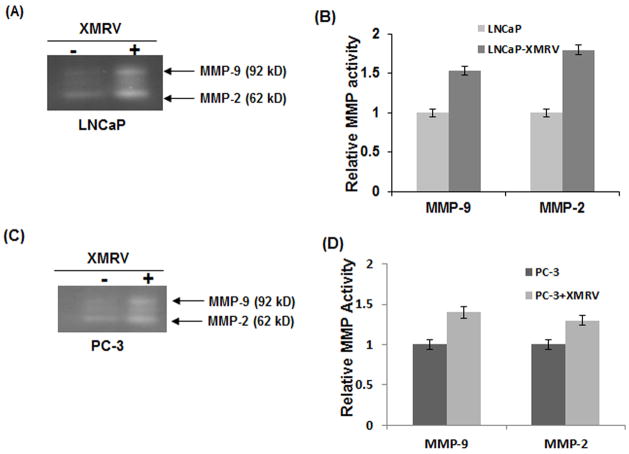

XMRV Infection Upregulates MMP Activity in Prostate Cancer Cells

Degradation of ECM and basement membrane components by MMPs are essential for tumor invasion (29–30). Previous studies have demonstrated that increased zymogen activity of MMP-2 and MMP-9 is associated with prostate cancer progression (32–33). Since XMRV increased the invasiveness of LNCaP and PC-3 cells (Fig. 3), we evaluated whether zymogen activation of MMP-2 and MMP-9 are affected by viral infection. To test this we carried out gelatin zymography and the results of zymogen activation of MMP-2 and MMP-9 are presented in Fig. 4. Consistent with the invasion data, XMRV infected cells showed higher activities of both MMP-2 and MMP-9 in comparison to uninfected cells. These observations suggested that elevated levels of MMP-2 and MMP-9 may in part contribute to the increased invasiveness of XMRV infected prostate cancer cells.

Fig. 4. MMP activities of prostate cancer cells are increased by XMRV infection.

Impact of XMRV infection on the zymogen activity of MMP-2 and MMP-9 in LNCaP (A–B) and PC-3 (C–D) cells. (A and C) Cell lysates were analyzed by Gelatin zymography and MMP activation was detected by commassie blue staining. (B and D) Densitometric measurement for quantitative analysis of relative MMP-2 and MMP-9 activities. The results are expressed as mean ± S.E. for three separate experiments. * p < 0.01 is for XMRV-infected cells compared with uninfected cells.

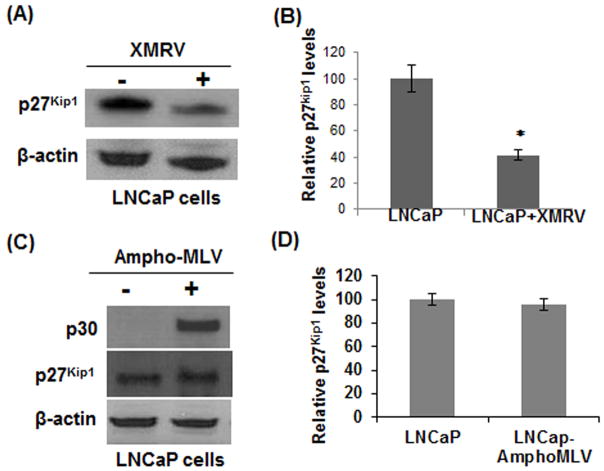

XMRV Infection Down-Regulates p27Kip1 in LNCaP Cells

p27Kip1 preferentially binds to and inactivates the cyclin/CDK complexes thereby inhibits cell cycle entry into S-phase (22–23). Since XMRV infection enhanced proliferation of LNCaP cells (Fig. 2A), we tested whether XMRV utilizes the p27Kip1 pathway for cell cycle deregulation. To analyze the levels of p27Kip1, we isolated total proteins from XMRV infected and uninfected LNCaP cells and compared the p27Kip1 levels by western blot analysis. The results in Fig. 5A revealed that p27Kip1 protein level in infected cells was substantially downregulated in comparison to the uninfected cells. Densitometry analysis indicated that p27Kip1 protein level was almost 50% lower in XMRV infected LNCaP cells (Fig. 5B). Subsequently, we examined whether downregulation of p27Kip1 is specific for XMRV or can be achieved by any related MLVs. For this, we infected LNCaP cells with amphotropic-MLV. The amphotropic-MLV are naturally occurring, exogenously acquired gammaretroviruses that can replicate in a wide range of cell types including human cells in vitro (34). Infection was confirmed by detection of MLV p30 by western blot (Fig. 5C). Results in Fig. 5C–D indicate that unlike XMRV, the protein level of p27Kip1 is minimally altered in ampho-MLV infected LNCaP cells.

Fig. 5. XMRV infection downregulates p27Kip1 in LNCaP cells.

(A) To determine the p27Kip1 proteins levels, cell lysates from uninfected and infected cells were analyzed by western blot. (B) XMRV induced decrease in p27Kip1 level was almost 50% as determined by densitometry. (C–D) Evaluation of p27Kip1 protein expression in LNCaP cells infected by ampho-MLV. In contrast to XMRV, Ampho-MLV had little/no impact on p27Kip1. The results are mean ± S.E. for three separate experiments. * p < 0.005 is for XMRV-infected cells compared with uninfected cells.

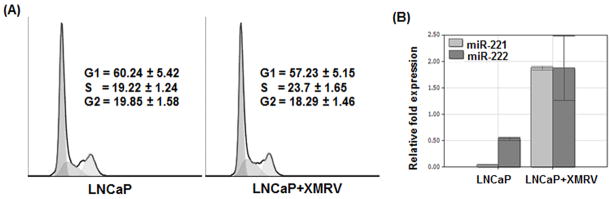

XMRV Infection Induces G1→S Transition in LNCaP Cells

Down-regulation of p27Kip1 activates cyclin/CDK complexes and helps in G1 to S transition of the cell cycle (22–23). Therefore, we evaluated whether downregulation of p27Kip1 leads to G1→S transition in XMRV infected LNCaP cells. To test this we carried out cell cycle analysis by measuring the DNA content in the cells by propidium iodide staining. Our data presented in Fig. 6A indicate higher percentages of infected cells in S phase in comparison to the uninfected cells. These data indicate that XMRV induced downregulation of p27Kip1 allows cell cycle transition, thereby enhances proliferation of prostate cancer cells.

Fig. 6. Downregulation p27Kip1 induces G1→S transition in LNCaP cells and is mediated by upregulation of miR-221 and miR-222.

(A) G1→S cell cycle transition was evaluated by propidium iodide staining by determining DNA content by flow cytometry. Three independent experiments were performed in triplicates. (B) XMRV induced downregulation of p27Kip1 is mediated by upregulation of miR-221 and miR-222 expression. For this experiment, total RNA isolated from cells were used in real time PCR analysis and relative fold expression of miR-221 and miR-222 were determined with reference to the expression of 5S ribosomal RNA. The results are expressed as mean ± S.E. for three separate experiments with triplicates.

XMRV Infection Upregulates miR-221 and miR-222 in LNCaP Cells

It has been demonstrated that p27Kip1 expression is controlled post-transcriptionally by miR-221 and miR-222 expression (35). In addition, overexpression of miR-221 and miR-222 has been shown to affect proliferation of prostate cancer cells (36). Since XMRV lacks regulatory proteins, we hypothesized that XMRV downregulates p27Kip1 by upregulating miR221 and miR222 in LNCaP cells. To test this, we isolated total RNAs from uninfected and XMRV infected LNCaP cells and then carried out real-time PCR analysis to evaluate miR-221 and miR-222 expression. Results in Fig. 6B reveal that expression of miR-221 and miR-222 in XMRV infected LNCaP cells are substantially higher than the uninfected cells. These results confirm our hypothesis that XMRV down-regulates p27Kip1 expression post-transcriptionally by up-regulating miR221 and miR222 in prostate cancer cells.

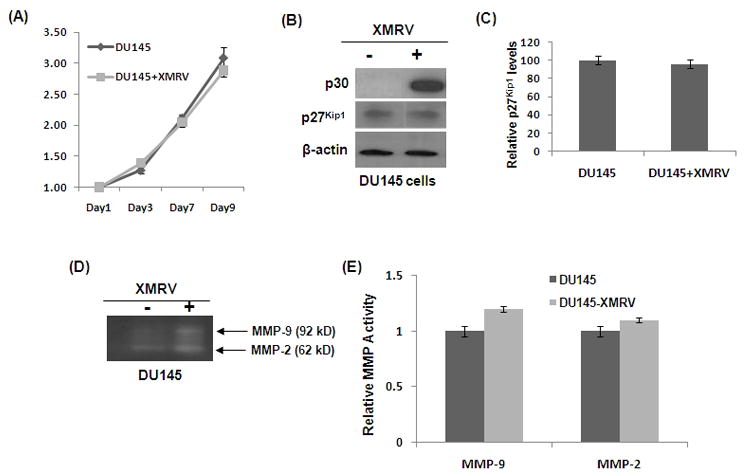

XMRV-induced p27Kip1Downregulation is Sensitive to Androgen

Published data suggests that androgens regulate p27Kip1 expression in the prostate (37–38). In addition, XMRV transcription and replication has been shown to be regulated by androgen (39). Given that LNCaP cells are androgen dependent, we evaluated whether the observed XMRV-induced molecular alterationsare dependent on androgen. To test this we used the androgen-independent prostate cancer cell line DU145 in our experiment. These cells were infected with XMRV and infection was confirmed by detecting XMRV p30 by western blot (Fig. 7B). Thereafter, we determined cellular proliferation, p27Kip1 levels and MMP activities in the uninfected and infected cells. Results in Fig. 7A revealed that proliferation of DU145 cells are not altered by XMRV infection. Furthermore, XMRV infection has little or no impact on p27Kip1 levels in these cells (Fig. 7B). However, XMRV infected DU145 cells showed slightly higher levels of MMP activities in comparison to the uninfected cells (Fig. 7C–D). In summary, our DU145 data indicate that XMRV-induced increase in proliferation and downregulation of p27Kip1 may be dependent on androgen.

Fig. 7. Androgen influences XMRV-induced molecular alterations in prostate cancer cells.

Androgen independent DU145 cells were infected with XMRV and infection was confirmed by detection of p30 protein (B). (A) Cellular proliferation of androgen dependent DU145 cells was determined by MTT assay as described in Fig. 2. (B) p27Kip1 levels was determined by western blot. (C) Densitometry analysis of p27Kip1 levels. (D) Zymogen activation of MMPs and (E) densitometry analysis was carried out as described in Fig. 4.

DISCUSSION

XMRV was initially detected in about 1% of nonmalignant prostatic stromal cells but not in the malignant epithelial cells of prostate tumors (1). Surprisingly, XMRV replication in prostatic epithelial cells was 10 fold higher than prostatic stromal cells (40). In a later study, XMRV proteins were detected in malignant epithelial cells but not in the stromal cells of high grade prostate tumors (2). Given that XMRV does not have host derived oncogenes (9), lacks direct transforming activity (18) and viral infection was not detected in all prostate tumor cells (1–3), a role of XMRV on initiation of prostate cancer remains speculative. Therefore, we evaluated whether XMRV has the potential to contribute towards disease progression. Recently Paprotka et al. have proposed that the association of XMRV with prostate cancer is due to contamination of the virus (12). However, these authors also suggest that XMRV may contribute to the proliferation and androgen independence of tumors derived from CWR22 xenografts.

Initially, we used the androgen-dependent “slow growing” LNCaP and androgen-independent “aggressive” PC- 3 carcinoma cells that mimic different stages of prostate cancer progression in vitro (20–21). Our data revealed that XMRV infection increased cellular proliferation of LNCaP cells but not that of PC-3 cells (Fig. 2A–B). This observation emphasized that XMRV could accelerate proliferation of slow growing cancer cells but not that of an aggressive prostate cancer cell. It is important to point out that we used chronically-infected cells to avoid a population of uninfected and infected cells that can exist under acute viral infection conditions. Furthermore, in acute infection conditions we could not rule out the possibility that proliferation of uninfected cells can be influenced by cellular/viral factors released from the infected cells. Since our goal was to decipher the underlying mechanism of accelerated proliferation of infected cells and acute viral infection can confound interpretation of our data, we used chronically infected cells in our experimental design. Establishment of chronic infection was confirmed by saturating levels of XMRV p30 protein in the infected cells by western blot analysis (Fig. S1). We assumed that saturated p30 level is an indication of chronic infection, since LNCaP cells are highly permissive for XMRV infection and any new infection should elevate total p30 levels.

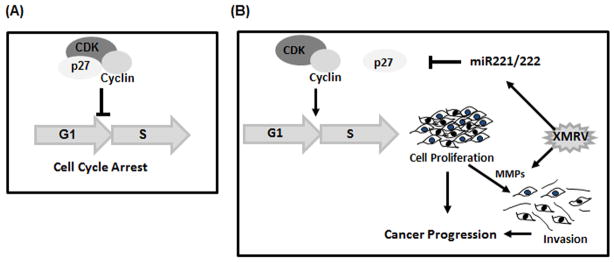

Our data also revealed that XMRV infection dramatically reduced p27Kip1 protein expression in LNCaP cells (Fig. 4A–B). Given that ampho-MLV infection did not alter p27Kip1 expression in these cells, downregulation of p27Kip1 seems to be specific for XMRV. These results suggested deregulation of cell cycle control as a potential mechanism for XMRV-induced cellular proliferation. In eukaryotic cells, G1 → S progression is regulated by cyclins/CDKs (Fig. 8A). p27Kip1 being a CDK inhibitor plays a critical role in cell proliferation as it inactivates the cyclin/CDK complexes (22–23). Given that XMRV downregulated p27Kip1, we envisioned G1→ S transition may contribute to the accelerated cellular proliferation of infected cells (Fig. 8B). Indeed, our flow cytometry analysis indicated that higher percentage of XMRV infected cells are in S phase in comparison to uninfected cells (Fig. 6). Importantly, p27Kip1 is also a putative tumor-suppressor gene and its expression is progressively decreased with increased prostate cancer grades (41–42). Since XMRV was detected in high grade prostate tumors, our data on p27Kip1 expression suggests that XMRV may serve as a cofactor in prostate cancer progression by accelerating cellular proliferation. Our results with androgen-independent DU145 cells revealed that XMRV infection have no effect on p27Kip1 expression and cellular proliferation (Fig. 7). A comparative analysis of results from DU145 and LNCaP cells indicate that downregulation of p27Kip1 and cellular proliferation may be dependent on androgen. This is not surprising since XMRV transcription and replication has been shown to be regulated by androgens (39).

Fig. 8. A model depicting a plausible role of XMRV in prostate cancer progression.

(A) In eukaryotic cells, p27Kip1 plays a critical role in cellular proliferation as it binds to the cyclin/CDK complexes and arrests cell cycle progression. (B) In XMRV infected cells, we hypothesize that by upregulating miR-221 and miR-222, XMRV downregulates p27Kip1 expression, thereby propels G1→S transition of the cell cycle. Subsequently, by upregulating the MMP activities that degrade ECM and basement membranes, XMRV enhances invasiveness of prostate cancer cells. Enhanced cellular proliferation and invasiveness of prostate cancer cells by XMRV infection may play a role in prostate cancer progression.

Although, p27Kip1 expression can be controlled at various levels (43–44), in physiological and pathological conditions post-transcriptional regulation is critical (45). It has been demonstrated that overexpression of miR-221 and miR-222 enhances growth of prostate cancer cells by post-transcriptionally regulating p27Kip1 expression (36). Our real time PCR data revealed that XMRV infection substantially upregulated miR-221 and miR-222 expression in LNCaP cells (Fig. 4C). Since miR-221 and miR-222 target p27Kip1 mRNA, upregulation of these miRNAs will significantly reduce p27Kip1 translation. This may serve in part as the underlying mechanism for the reduced levels of p27Kip1 protein in XMRV infected cells. However we cannot rule out the contributions of transcriptional regulation and protein degradation on p27Kip1 downregulation. XMRV being a gammaretrovirus does not encode accessory proteins (9) that are known to regulate host gene expression in complex retroviruses such as HIV (46). Given that XMRV integration has been documented near miRNA genes of host genome (15), our data supports the unique mechanisms utilized by gammaretroviruses to control host gene expressions (47–48).

MMPs play critical roles in cancer since they degrade components of the ECM and basement membranes that otherwise serve as barriers for tumor progression (49). Previous studies in tissue samples have demonstrated the association of increasing MMP-2 and MMP-9 activities with prostate tumor invasion and metastasis (32–33). Given that XMRV infection accelerated the invasiveness of the prostate cancer cells (Fig. 3A–B), we evaluated whether activities of MMP-2 and MMP-9 were modulated by viral infection. Our data revealed that XMRV infected LNCaP cells have increased MMP-2 and MMP-9 zymogen activity (Fig. 3C–D) that most likely contributed to the accelerated invasiveness of these cells. The MMP-2/9 activities were also increased marginally in the androgen-independent PC-3 and DU145 cells. Although the mechanism by which XMRV upregulated the MMP activity is unclear from our data, it is possible that XMRV induces the zymogen activity through a pathway that is independent of androgen. Since MMPs play important roles in cancer progression, our invasion and MMP data underscore our argument on a potential role of XMRV in cancer progression.

CONCLUSIONS

The acquisition of a malignant phenotype by cells is a highly complex process. In addition to viral infection, the context of genetic, epigenetic, hormonal, and immunological factors in cells play essential roles in malignant transformation (50). Since XMRV lacks transforming ability by itself, viral infection alone might not be sufficient to induce oncogenesis. In addition, the recent report by Paprotka et al. on possible contamination of XMRV in prostate tumors also cast doubt on the initiation of prostate carcinogenesis by XMRV. However, our results implicate that in a cellular microenvironment where a transformation process has been initiated, XMRV infection may accelerate cellular proliferation and invasion of prostate tumors. In conclusion, we hypothesize that XMRV may serve as a cofactor for prostate cancer progression by enhancing tumor growth and invasion. However, further studies involving primary and non-transformed cells are warranted to strengthen our hypothesis.

Supplementary Material

(A) LNCaP cells were infected with XMRV and infection was analyzed by western blot analysis of cell lysates for the detection of XMRV p30 protein. (B) Relative p30 levels in XMRV infected cells were determined with reference to β-actin. Saturation of p30 was achieved day 7 post-infection indicating most of the cells were infected with XMRV.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Sandra Ruscetti (NCI-Frederick) for the antibodies, Dr. Alan Rein (NCI-Frederick) for ampho-MLV and Dr. James Hildreth of Meharry Medical College-CAHDR for LNCaP cells. We thank Dr. Vineet KewalRamani for technical guidance. This work is partly supported by grants to CD from NIH (R00DA024558, R03DA30896) and Vanderbilt-Meharry CFAR (CTSA).

References

- 1.Urisman A, Molinaro RJ, Fischer N, Plummer SJ, Casey G, Klein EA, Malathi K, Magi-Galluzzi C, Tubbs RR, Ganem D, Silverman RH, DeRisi JL. Identification of a novel gammaretrovirus in prostate tumors of patients homozygous for R462Q RNASEL variant. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e25, 0211–0225. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 2.Schlaberg R, Choe DJ, Brown KR, Thaker HM, Singh IR. XMRV is present in malignant prostatic epithelium and is associated with prostate cancer, especially high-grade tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:16351–16356. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906922106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 3.Arnold RS, Makarova NV, Osunkoya AO, Suppiah S, Scott TA, Johnson NA, Bhosle SM, Liotta D, Hunter E, Marshall FF, Ly H, Molinaro RJ, Blackwell JL, Petros JA, et al. XMRV infection in patients with prostate cancer: novel serologic assay and correlation with PCR and FISH. J Urol. 2010;75:755–61. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knouf EC, et al. Multiple integrated copies and high-level production of the human retrovirus XMRV from 22Rv1 prostate carcinoma cells. J Virol. 2009;83:7353–7356. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00546-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fischer N, Hellwinkel O, Schulz C, Chun FK, Huland H, Aepfelbacher M, Schlomm T. Prevalence of human gammaretrovirus XMRV in sporadic prostate cancer. J Clin Virol. 2008;43:277–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2008.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hohn O, Krause H, Barbarotto P, Niederstadt L, Beimforde N, Denner J, Miller K, Kurth R, Bannert N. Lack of evidence for xenotropic murine leukemia virus-related virus (XMRV) in German prostate cancer patients. Retrovirology. 2009;6:92. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-6-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verhaegh GW, de Jong AS, Smit FP, et al. Prevalence of human xenotropic murine leukemia virus-related gammaretrovirus (XMRV) in Dutch prostate cancer patients. Prostate. 2010;71:415–20. doi: 10.1002/pros.21255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aloia AL, Sfanos KS, Isaacs WB, et al. XMRV: a new virus in prostate cancer? Cancer Res. 2010;70:10028–33. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silverman RH, Nguyen C, Weight CJ, Klein EA. The human retrovirus XMRV in prostate cancer and chronic fatigue syndrome. Nat Rev Urol. 2010;7:392–402. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2010.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hué S, Gray ER, Gall A, Katzourakis A, Tan CP, Houldcroft CJ, McLaren S, Pillay D, Futreal A, Garson JA, Pybus OG, Kellam P, Towers GJ. Disease-associated XMRV sequences are consistent with laboratory contamination. Retrovirology. 2010;7:111. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-7-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robinson MJ, Erlwein OW, Kaye S, Weber J, Cingoz O, Patel A, Walker MM, Kim WJ, Uiprasertkul M, Coffin JM, McClure MO. Mouse DNA contamination in human tissue tested for XMRV. Retrovirology. 2010;7:108. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-7-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paprotka T, Delviks-Frankenberry KA, Cingöz O, Martinez A, Kung H-J, Tepper CG, Hu W-S, Fivash MJ, Jr, Coffin MJ, Pathak VK. Recombinant Origin of the Retrovirus XMRV. Science. 2011 May 31; doi: 10.1126/science.1205292. Paper in press. 2011/Page 1/10.1126/science.1205292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh I, Schlaberg R, Shin CH, Thaker H. CSHL Retroviral Meeting Presentation, XMRV, or a related virus, is present in a large percentage of men and is localized to the androgen secreting Leydig cells of the testis Abstract number 245 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Onlamoon N, Das Gupta J, Sharma P, Rogers K, Suppiah S, Rhea J, Molinaro RJ, Gaughan C, Dong B, Klein EA, Qiu X, Devare S, Schochetman G, Hackett J, Jr, Silverman RH, Villinger F. Infection, Viral Dissemination, and Antibody Responses of Rhesus Macaques Exposed to the Human Gammaretrovirus XMRV. J Virol. 2011;85:4547–57. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02411-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alian A, Sela-Donenfeld D, Panet A, Eldor A. Avian hemangioma retrovirus induces cell proliferation via the envelope (env) gene. Virology. 2000;276:161–168. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu SL, Miller AD. Oncogenic transformation by the jaagsiekte sheep retrovirus envelope protein. Oncogene. 2007;26:789–801. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim S, Kim N, Dong B, Boren D, Lee SA, Das Gupta J, Gaughan C, Klein EA, Lee C, Silverman RH, Chow SA. Integration site preference of xenotropic murine leukemia virus-related virus, a new human retrovirus associated with prostate cancer. J Virol. 2008;82:9964–77. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01299-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Metzger MJ, Holguin CJ, Mendoza R, Miller AD. The prostate cancer-associated human retrovirus XMRV lacks direct transforming activity but can induce low rates of transformation in cultured cells. J Virol. 2009;84:1874–1880. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01941-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dong B, Kim S, Hong S, Das Gupta J, Malathi K, Klein EA, Ganem D, DeRisi JL, Chow SA, Silverman RH. An infectious retrovirus susceptible to an IFN antiviral pathway from human prostate tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:1655–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610291104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Horoszewicz JS, Leong SS, Kawinski E, Karr JP, Rosenthal H, Chu TM, Mirand EA, Murphy GP. LNCaP Model of Human Prostatic Carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1983;43:1809–1818. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dozmorov MG, Hurst RE, Culkin DJ, Kropp BP, Frank MB, Osban J, Penning TM, Lin H-K. Unique patterns of molecular profiling between human prostate cancer LNCaP and PC-3 cells. The Prostate. 2009;69:1077–1090. doi: 10.1002/pros.20960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sherr CJ, Roberts JM. Inhibitors of mammalian G1 cyclin-dependent kinases. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1149–1163. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.10.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stacy W, Blain SW, Scher HI, Cordon-Cardo C, Koff A. p27 as a target for cancer therapeutics. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:111–115. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sicinski P, Zacharek S, Kim C. Duality of p27Kip1 function in tumorigenesis. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1703–1706. doi: 10.1101/gad.1583207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fero ML, Rivkin M, Tasch M, Porter P, Carow CE, Firpo E, Polyak K, Tsai LH, Broudy V, Perlmutter RM, Kaushansky K, Roberts JM. A syndrome of multiorgan hyperplasia with features of gigantism, tumorigenesis, and female sterility in p27(Kip1)-deficient mice. Cell. 1996;85:733–744. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81239-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakayama K, Ishida N, Shirane M, Inomata A, Inoue T, Shishido N, Horii I, Loh DY, Nakayama K. Mice lacking p27(Kip1) display increased body size, multiple organ hyperplasia, retinal dysplasia, and pituitary tumors. Cell. 1996;85:707–720. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81237-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cote R, Shi Y, Groshen S, Feng A, Corodon-Cardo C, Skinner D, Lieskovosky G. Association of p27Kip1 levels with recurrence and survival in patients with stage C prostate carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:916–920. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.12.916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Di Cristofano A, De Acetis M, Koff A, Cordon-Cardo C, Pandolfi PP. Pten and p27KIP1 cooperate in prostate cancer tumor suppression in the mouse. Nature Genetics. 2000;27:222–224. doi: 10.1038/84879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sternlicht MD, Werb Z. How matrix metalloproteinases regulate cell behavior. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2001;17:463–516. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.17.1.463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Curran S, Murray GI. Matrix metalloproteinases: Molecular aspects of their roles in tumor invasion and metastasis. Eur J Cancer. 2000;36:1621–1630. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(00)00156-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sato E, Furuta RA, Miyazawa T. An endogenous murine leukemia viral genome contaminant in a commercial RT-PCR Kit is amplified using standard primers for XMRV. Retrovirology. 2010 Dec 20;7(1):110. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-7-110. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sauer CG, Kappeler A, Spath M, et al. Expression and activity of matrix metalloproteinases-2 and -9 in serum, core needle biopsies and tissue specimens of prostate cancer patients. Virchows Arch. 2004;444:518–526. doi: 10.1007/s00428-004-1016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wood M, Fudge K, Mohler JL, et al. In situ hybridization studies of metalloproteinases 2 and 9 and TIMP-1 and TIMP-2 expression in human prostate cancer. Clin Exp Metastasis. 1997;15:246–258. doi: 10.1023/a:1018421431388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Howard TM, Sheng Z, Wang M, Wu Y, Rasheed S. Molecular and phylogenetic analyses of a new Amphotropic murine leukemia virus (MuLV-1313) Virology J. 2006;3:101. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-3-101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.le Sage C, Nagel R, Agami R. Diverse ways to control p27Kip1 function: miRNAs come into play. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:2742–2749. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.22.4900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Galardi S, Mercatelli N, Giorda E, Massalini S, Frajese GV, Ciafre SA, Farace MG. miR-221 and miR-222 Expression Affects the Proliferation Potential of Human Prostate Carcinoma Cell Lines by Targeting p27Kip1. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:23716–23724. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701805200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Macri E, Loda M. Role of p27 in prostate carcinogenesis. Cancer and Metastasis Rev. 1999;17:337–334. doi: 10.1023/a:1006133620914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blain SW, Scher HI, Cordon-Cardo C, Koff A. p27 as a target for cancer therapeutics. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:111–115. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dong B, Silverman RH. Androgen stimulates transcription and replication of XMRV (xenotropic murine leukemia virus-related virus) J Virol. 2009;84:1648–1651. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01763-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hong S, Klein EA, Gupta JD, et al. Fibrils of prostatic acid phosphatase fragments boost infections with XMRV (xenotropic murine leukemia virus-related virus), a human retrovirus associated with prostate cancer. J Virol. 2009;83:6995–7003. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00268-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsihlias J, Kapusta L, Slingerland J. The prognostic significance of altered cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors in human cancer. Annu Rev Med. 1999;50:401–423. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.50.1.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang RM, Naitoh J, Murphy M, Wang HJ, Phillipson J, deKernion JB, Loda M, Reiter RE. Low p27 expression predicts poor disease-free survival in patients with prostate cancer. J Urol. 1998;159:941–945. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koff A. How to decrease p27Kip1 levels during tumor development. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:75–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Servant MJ, Coulombe P, Turgeon B, Meloche S. Differential regulation of p27(Kip1) expression by mitogenic and hypertrophic factors: Involvement of transcriptional and posttranscriptional mechanisms. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:543–56. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.3.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Belletti B, Nicoloso MS, Schiappacassi M, Chimienti E, Berton S, Lovat F, Colombatti A, Baldassarre G. p27(kip1) functional regulation in human cancer: a potential target for therapeutic designs. Curr Med Chem. 2005;12:1589–1605. doi: 10.2174/0929867054367149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Frankel AD, Young JA. HIV-1: Fifteen Proteins and an RNA. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:1–25. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yamamoto N, Takase-Yoden S. Friend murine leukemia virus A8 regulates Env protein expression through an intron sequence. Virology. 2009;385:115–125. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yamamoto N, Takase-Yoden S. Analysis of cis-regulatory elements in the 5′ untranslated region of murine leukemia virus controlling protein expression. Microbiol Immunol. 2009;53:140–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2008.00103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Curran S, Murray GI. Matrix metalloproteinases: Molecular aspects of their roles in tumor invasion and metastasis. Eur J Cancer. 2000;36:1621–1630. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(00)00156-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morris JD, Eddleston AL, Crook T. Viral infection and cancer. Lancet. 1995;346:754–758. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91510-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(A) LNCaP cells were infected with XMRV and infection was analyzed by western blot analysis of cell lysates for the detection of XMRV p30 protein. (B) Relative p30 levels in XMRV infected cells were determined with reference to β-actin. Saturation of p30 was achieved day 7 post-infection indicating most of the cells were infected with XMRV.