Abstract

Eribis peptide 94 (EP 94) is a novel enkephalin derivative which binds with high potency to μ and δ opioid receptors with less affinity for the κ opioid receptor. This compound has recently been shown to produce an acute reduction in myocardial infarct size in the anesthetized pig and rat partially via an eNOS- and KATP channel-dependent mechanism. EP 94 also was found to produce a chronic reduction in infarct size 24 hrs post drug administration via the upregulation of iNOS in rats. In spite of these findings, no data have emerged in which the opioid receptor subtype responsible for cardioprotection has been identified and the site of action, heart, other peripheral organs or the CNS have not been addressed. In the current study, EP 94, was administered in 2 divided doses (0.5 ug/kg, iv) at 5 and 10 min into the ischemic period and the opioid antagonists were administered 10 min prior to the onset of the 30 min ischemic period. The selective antagonists used were the μ receptor antagonist CTOP, the δ receptor antagonists, naltrindole and BNTX and the κ receptor antagonist, nor-BNI. Surprisingly, only CTOP completely blocked the cardioprotective effect of EP 94, whereas, naltrindole, BNTX and nor-BNI had modest but nonsignificant effects. Since there is controversial evidence suggesting that μ receptors may be absent in the adult rat myocardium, it was hypothesized that the protective effect of EP 94 may be mediated by an action outside the heart, perhaps in the CNS. To test this hypothesis, rats were pretreated with the nonselective opioid antagonist, naloxone HCl (NAL), which penetrates the blood brain barrier (BBB) or naloxone methiodide (NME), the quaternary salt of NAL, which does not penetrate the BBB prior to EP 94 administration. In support of a CNS site of action for EP 94, NAL completely blocked its cardioprotective effect, whereas, NME had no effect. These results suggest that EP 94 reduces IS/AAR in the rat primarily via activation of central μ opioid receptors.

INTRODUCTION

There is an increasing body of evidence suggests that exogenous1 and endogenous2 opioids produce marked cardioprotective effects either acutely or delayed 24–72 h post opioid administration.3 More recently, Peart et al.4 have shown that chronic treatment with morphine produces a long-lasting cardioprotective effect that can persist for at least a week after drug withdrawal. Most studies suggest that these effects are mediated via δ opioid receptors5 although there is also evidence to support a role for κ 6 and μ 7 receptors as well depending on the species and age of the animal and the selectivity of the agonists and antagonists employed. In this regard, activation of opioid,5 adenosine8 and bradykinin9 G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) has been universally shown to trigger the phenomenon of ischemic preconditioning (IPC)

With the importance of opioids in acute or chronic IPC well established and a major role for the δ receptor as being the predominant receptor subtype involved in mediating opioid-induced cardioprotection, Eribis Pharmaceutical AB synthesized a novel enkephalin derivative, Eribis 94 (EP 94), for its potential beneficial effect in reducing infarct size in patients suffering an acute myocardial infarction. In support of a cardioprotective role for EP 94, Karlsson et al.10 demonstrated in pigs that an intravenous dose of EP 94 reduced infarct size whether administered early or late during a 40 min ischemic period. They also found that EP 94 given intracoronary at 30 min of ischemia significantly reduced infarct size which suggested that EP 94 was having a direct myocardial effect to produce cardioprotection. Finally, these same investigators found an increase in phosphorylation at eNOS Ser1177 which presumably would result in increased nitric oxide (NO) release following EP 94 treatment. The opioid receptor subtype mediating these effects in the pig heart was not determined.

More recently, preliminary results from our laboratory found that EP 94 produced a dose-related reduction in infarct size in the intact anesthetized rat model of ischemia/reperfusion injury. It was also demonstrated that EP 94 produces an acute effect and a second window effect to reduce infarct size and that these protective effects were mediated by activation of eNOS acutely and upregulation of iNOS chronically. Further evidence suggests that the sarcolemmal KATP and mitochondrial KATP channel may be mediating the effect of NO to produce cardioprotection in this model although the reverse sequence may also be possible. Nevertheless, the opioid receptor responsible for triggering and/or mediating the protective effect of EP 94 is still not known and is one major objective of the current study. The second major objective was to determine if the effect of EP 94 is the result of an effect directly on the heart or whether this compound may have a peripheral or a central component involved in producing its cardioprotective effect.

Methods

Studies followed the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the United States National Institutes of Health (NIH Publications No. 85-23, revised 1996). The protocols were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Medical College of Wisconsin.

In vivo surgical preparation

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (250–300 g) were anesthetized with 100 mg/kg of Inactin, placed on a heating pad and a tracheotomy performed and the rat ventilated with roon air supplemented with 100% oxygen. Catheters were placed in the carotid artery and jugular vein for the measurement of systemic blood pressure, heart rate, blood gases and for administration of drugs or vehicle. The heart was exposed by a left thoracotomy and the left coronary artery isolated and a suture placed around it to produce an occlusion followed by reperfusion. The heart was subjected to 30 min of total coronary artery occlusion followed by 2 hrs of reperfusion at which time the artery was reoccluded and Evans Blue Dye injected into the jugular vein to stain the nonischemic area of the heart blue. Subsequently, the heart was arrested with a bolus of 10% KCl and removed for the measurement of infarct size. After heart removal, it was washed in buffer and cut in a bread loaf fashion into 5–6 pieces and the blue stained normal region and the ischemic region separated and placed in separate vials containing triphenyltetrazolium chloride staining solution and incubated at 37°C in phosphate buffer at pH 7.40 for approximately 15 min. Subsequently, the pieces of tissue were placed into vials containing formaldehyde and stored overnight at room temperature and infarct size determined by gravimetry the following day. Infarct size (IS) was expressed as a percent (%) of the area at risk (IS/AAR, %) as determined by our dual staining technique. In the AAR, the dark red color represents noninfarcted tissue, whereas, the infarcted tissue remains a pale yellow color.

Experimental protocols

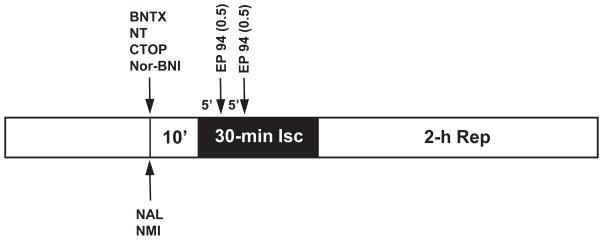

The various drugs and protocols are shown in Fig. 1. Sixteen groups of 9 animals per group (144 total) were subjected to the 30 min ischemia/2 hrs reperfusion protocol. The opioid agonist EP 94 (0.5 ug/kg, iv each dose) was administered at 5 and 10 min into the ischemic period in all experiments and the selective opioid receptor antagonists, CTOP (μ, 0.1 mg/kg, iv) naltrindole (δ, 5.0 mg/kg, iv) BNTX (δ 1, 3.0 mg/kg, iv) or nor-BNI (κ, 0.3 mg/kg, iv) were administered at 10 min prior to ischemia. Naloxone (NL), a nonselective opioid receptor antagonist with peripheral and central actions, or naloxone methiodide (NMI), a nonselective peripheral opioid receptor blocker were administered 10 min prior to EP 94 administration. Selective antagonist doses were chosen based on previous experiments from our laboratory and the literature11 which showed the selectivity of each antagonist for its receptor with the highest affinity.

Figure 1.

A schematic diagram of the various experimental groups. Abbreviations: BNTX = 7-benzylidenenaltrexone, NT = naltrindole, CTOP = D-Phe-Cys-Tyr-D-Trp-Orn-Thr-Pen-Thr-NH2 , nor-BNI = Norbinaltorphimine, NL =Naloxone hydrochloride, NMI = Naloxone methiodide.

Statistics

Data were expressed as mean ± SEM. All data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism v.4.0. Comparison between groups in hemodynamics and blood gases was performed using a two-way ANOVA with post-hoc analysis by Bonferroni’s test. A one way ANOVA was used to compare infarct sizes between groups followed by Tukeys post hoc test. A probability value of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Exclusions

A total of 150 rats were entered into the protocols shown in Fig.1. Two rats were excluded due intractable ventricular fibrillation, abnormal blood gases (2 rats) and severe hypotension (mean arterial pressure less than 40 mm Hg, 2 rats). Therefore, 144 rats were included in the data analysis (16 groups of 9 rats).

Hemodynamics and blood gases

There were no significant differences in the baseline values for heart rate and mean arterial pressure between all groups and at 30 min of ischemia and 2 hrs of reperfusion (Data not shown). Similarly, there were no differences in blood gases or body temperature between groups throughout the experiment.

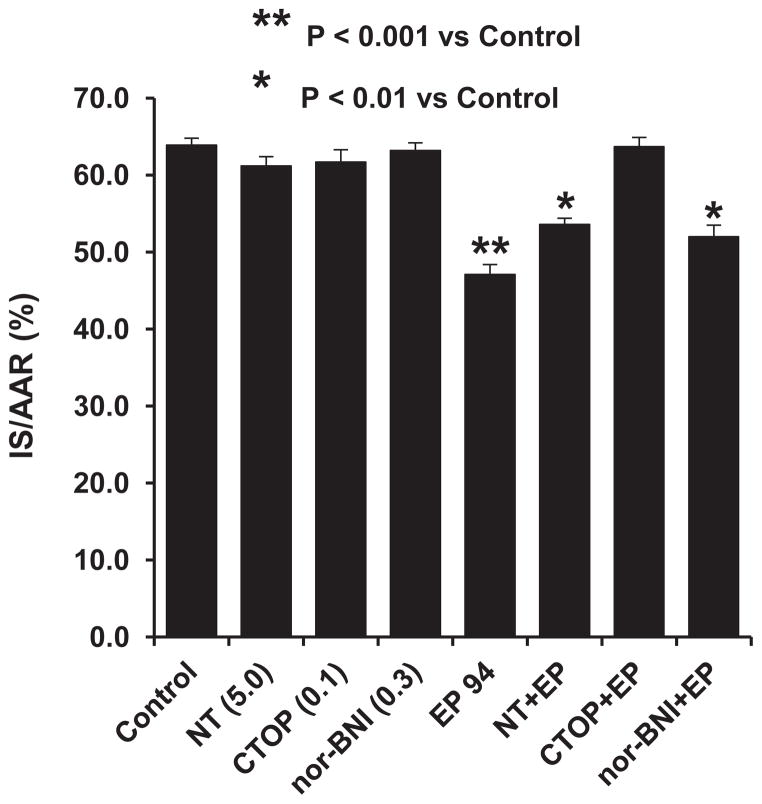

Opioid receptor subtype studies

In this series of rats, we attempted to determine which opioid receptor subtype, μ, δ, or κ, was responsible for the cardioprotective effect of EP 94 in our rat infarct model. The selective antagonists chosen were CTOP, a selective μ receptor antagonist, naltrindole, a selective δ receptor antagonist and nor-BNI, a selective κ receptor antagonist. Interestingly and surprisingly, the selective δ and κ antagonists were only modestly effective at blocking the cardioprotective effect of EP 94 whereas, CTOP, the selective μ antagonist completely abolished the effect of EP 94 (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

The effect of the selective opioid antagonists, NT (5 mg/kg, iv), CTOP (0.1 mg/kg, iv) and nor-BNI (0.3 mg/kg, iv) on EP 94-induced cardioprotection in rats. N = 9/group. *P<0.01, **P<0.001 vs. Control group.

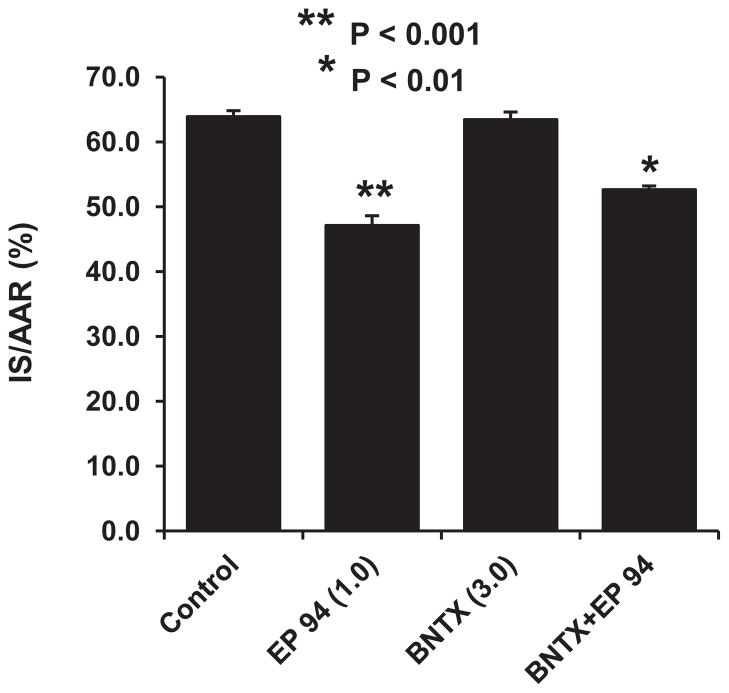

In the next series of experiments, we used the selective δ 1 receptor antagonist, BNTX, to further determine if we would observe different results to those previously obtained with the nonselective δ 1,2 antagonist naltrindole. The results are shown in Fig. 3 and suggest that BNTX produced a nearly identical mild blockade of EP 94-induced infarct size reduction as we previously demonstrated with naltrindole. Taken together, these data strongly suggest that EP 94 is acting primarily via an μ opioid receptor in our rat model of infarction.

Figure 3.

The effect of the selective δ 1 opioid receptor antagonist, BNTX (3 mg/kg, iv), on EP 94-induced cardioprotection in rats. N = 9/group. *P<0.01, **P<0.001 vs. Control group.

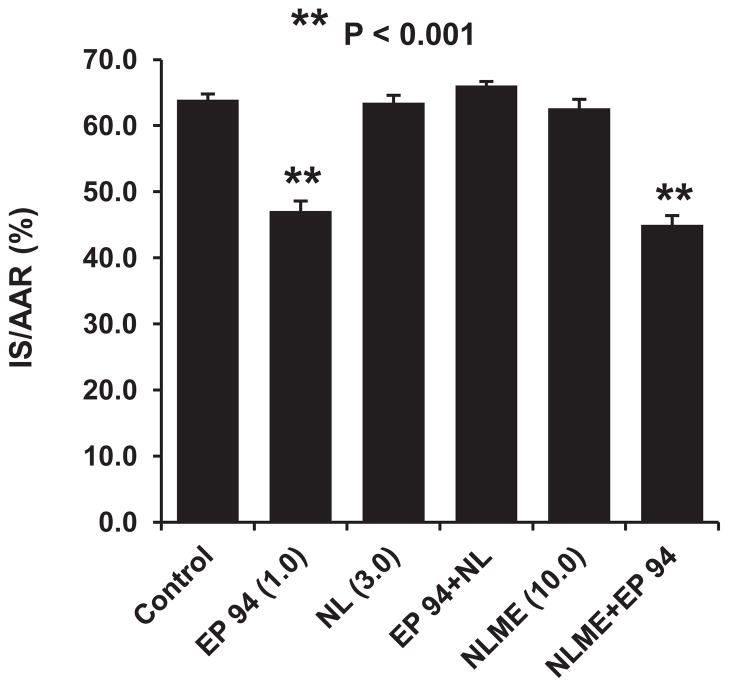

Site of action of EP 94

Since there is strong evidence that the adult rat myocardium does not express μ opioid receptors,12 we hypothesized that EP 94’s major protective effect is mediated in the CNS and not directly on the heart. To test this hypothesis, we used 2 naloxone derivatives, naloxone HCl which penetrates into the CNS and naloxone methiodide which does not pass the blood brain barrier. Interestingly, naloxone HCl totally blocked the cardioprotective effect of EP 94, whereas, naloxone methiodide produced no antagonism of EP 94-induced cardioprotection (Fig. 4). These results further suggest that the cardioprotective effect of EP 94 may be initiated in the CNS via activation of μ opioid receptors and not directly on the heart in this model.

Figure 4.

The effect of the nonselective opioid receptor antagonist, naloxone HCl (3.0 mg/kg, iv) which penetrates the blood brain barrier and its quaternary derivative, naloxone methiodide (10.0 mg/kg, iv) which only blocks peripheral opioid receptors, on the EP 94-induced cardioprotection in rats. N = 9/group. **P<0.001 vs. Control group.

Discussion

The results of the present study confirm our previous observation that the enkephalin derivative, EP 94, possesses potent cardioprotective effects to reduce infarct size in an in vivo rat model of infarction. The magnitude of the effect of EP 94 to reduce IS/AAR (%) was equal to that seen with most opioid agonists studied in this model including morphine,13 although EP 94 is the most potent compound we have investigated. There were no noticeable effects of EP 94 on peripheral hemodynamics including heart rate and blood pressure.

Of great interest was the current series of experiments where we used selective opioid receptor antagonists, CTOP (μ), Naltrindole (δ) and nor-BNI (κ) alone and prior to EP 94 administration. Intriguing data were obtained with CTOP (0.1 mg/kg, iv), the selective μ receptor antagonist. Since there are data that demonstrate the lack of cardiac μ receptors in the adult rat heart,14 it was unexpected when the selectiveμ antagonist, CTOP, completely blocked the protective effect of EP 94, whereas, the δ and κ antagonists, naltrindole and nor-BNI, only partially and modestly antagonized the effect of EP 94. In regards to the presence or absence of μ opioid receptors in the heart, several recent papers suggest that there are indeed μ opioid receptors in the heart7, 15 which may mediate cardioprotection so this is still an area of controversy. However, since most investigators, including ourselves, have previously shown that the δ 1 opioid receptor is the major one responsible for the cardioprotective effects of opioids,16 we chose to look at the more selective δ 1 antagonist, BNTX,17 to determine if similar effects would be obtained to those obtained with naltrindole, the nonselective δ 1 and δ 2 antagonist . In agreement with the data observed in the naltrindole experiments, we found that BNTX had a nearly identical modest but nonsignificant blocking effect against EP 94-induced cardioprotection. Another way to approach the receptor subtype puzzle and the site of action problem would be to use an isolated Langendorff rat heart or an isolated cardiomyocyte model with EP 94 treatment alone or in combination with the selective opioid anagonist. These experiments would help determine if EP 94 is acting centrally or peripherally or both, and the specific opioid receptor involved.

In two other series of experiments, we used naloxone, a nonselective central and peripheral-acting opioid antagonist and naloxone methiodide,17 a nonselective peripherally-acting opioid antagonist to be certain that EP 94 is acting via an opioid receptor and to further determine if its protective effect is mediated via a central nervous system or peripheral effect. The results showed that naloxone completely blocked the cardioprotective effect of EP 94 whereas, naloxone methiodide had no effect. These results clearly suggest that EP 94 is acting on anμ opioid receptor and that its major site of action is most likely central in nature. It is possible that the dose (10 mg/kg) of naloxone methiodide was not high enough to block μ receptors as this compound is much less potent than naloxone as a μ receptor blocker.17

The most important question which the present results have not addressed is the mechanism by which central m opioid receptor activation produces cardioprotection by a central site of action. There are known to be high concentrations of μ opioid receptors in the brain, particularly in the medial thalamus, the medium raphe and the pariaqueductal gray as well as the striatum and hypothalamus.18 These regions may be activated by opioids such as EP 94 and via descending neural pathways may exert cardioprotective effects in the heart via activation of the parasympathetic system or by antagonism of the sympathetic system. All of this is pure conjecture and there are no hard data to support this hypothesis. Only a well-performed investigation of specific neural pathways activated by opioids will answer this question.

In summary, this is the first demonstration to our knowledge which suggests that a specific opioid agonist is able to produce a potent cardioprotective effect via activation of central μ opioid receptors. However, caution is warranted in interpreting these results based on one dose of selective opioid antagonists and more complete dose-response studies are needed in future experiments to enhance confidence in the validity of these fascinating findings. In addition, experiments in other animal species are warranted as there may be important differences in opioid receptor numbers and subtypes depending on animal species. Currently, we have ongoing studies determining the receptor subtype involved in the protection produced by EP 94 in the porcine heart.

Acknowledgments

These experiments were supported by funds obtained from Eribis Pharmaceuticals AB and NIH Grant HL074314 (GJG).

References

- 1.Schultz JE, Rose E, Yao Z, Gross GJ. Evidence for involvement of opioid receptors in ischemic preconditioning in rat hearts. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:H2157–2161. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.268.5.H2157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schulz R, Gres P, Heusch G. Role of endogenous opioids in ischemic preconditioning but not in short-term hibernation in pigs. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;280:H2175–2181. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.5.H2175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fryer RM, Hsu AK, Eells JT, Nagase H, Gross GJ. Opioid-induced second window of cardioprotection: potential role of mitochondrial KATP channels. Circ Res. 1999;84:846–851. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.7.846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peart JN, Gross GJ. Morphine-tolerant mice exhibit a profound and persistent cardioprotective phenotype. Circulation. 2004;109:1219–1222. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000121422.85989.BD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gross GJ. Role of opioids in acute and delayed preconditioning. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2003;35:709–718. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(03)00135-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peart JN, Gross ER, Reichelt ME, Hsu A, Headrick JP, Gross GJ. Activation of kappa-opioid receptors at reperfusion affords cardioprotection in both rat and mouse hearts. Basic Res Cardiol. 2008;103:454–463. doi: 10.1007/s00395-008-0726-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Head BP, Patel HH, Roth DM, Lai NC, Niesman IR, Farquhar MG, Insel PA. G-protein-coupled receptor signaling components localize in both sarcolemmal and intracellular caveolin-3-associated microdomains in adult cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:31036–31044. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502540200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen MV, Downey JM. Adenosine: trigger and mediator of cardioprotection. Basic Res Cardiol. 2008;103:203–215. doi: 10.1007/s00395-007-0687-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen MV, Philipp S, Krieg T, Cui L, Kuno A, Solodushko V, Downey JM. Preconditioning-mimetics bradykinin and DADLE activate PI3-kinase through divergent pathways. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;42:842–851. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karlsson LO, Grip L, Bissessar E, Bobrova I, Gustafsson T, Kavianipour M, Odenstedt J, Wikstrom G, Gonon AT. Opioid receptor agonist Eribis peptide 94 reduces infarct size in different porcine models for myocardial ischaemia and reperfusion. Eur J Pharmacol. 2011;651:146–151. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.10.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raynor K, Kong H, Chen Y, Yasuda K, Yu L, Bell GI, Reisine T. Pharmacological characterization of the cloned kappa-, delta-, and mu-opioid receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 1994;45:330–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zimlichman R, Gefel D, Eliahou H, Matas Z, Rosen B, Gass S, Ela C, Eilam Y, Vogel Z, Barg J. Expression of opioid receptors during heart ontogeny in normotensive and hypertensive rats. Circulation. 1996;93:1020–1025. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.5.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schultz JJ, Hsu AK, Gross GJ. Ischemic preconditioning and morphine-induced cardioprotection involve the delta (delta)-opioid receptor in the intact rat heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1997;29:2187–2195. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1997.0454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zatta AJ, Kin H, Yoshishige D, Jiang R, Wang N, Reeves JG, Mykytenko J, Guyton RA, Zhao ZQ, Caffrey JL, Vinten-Johansen J. Evidence that cardioprotection by postconditioning involves preservation of myocardial opioid content and selective opioid receptor activation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294:H1444–1451. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01279.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schultz JE, Gross GJ. Opioids and cardioprotection. Pharmacol Ther. 2001;89:123–137. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(00)00106-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fryer RM, Wang Y, Hsu AK, Nagase H, Gross GJ. Dependence of delta1-opioid receptor-induced cardioprotection on a tyrosine kinase-dependent but not a Src-dependent pathway. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;299:477–482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lewanowitsch T, Irvine RJ. Naloxone and its quaternary derivative, naloxone methiodide, have differing affinities for mu, delta, and kappa opioid receptors in mouse brain homogenates. Brain Res. 2003;964:302–305. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)04117-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pasternak GW, Snyder SH. Identification of novel high affinity opiate receptor binding in rat brain. Nature. 1975;253:563–565. doi: 10.1038/253563a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]