Abstract

Chemoradiation (CRT) is a valuable treatment option for advanced hypopharyngeal squamous cell cancer (HSCC). However, long-term toxicity and quality of life (QOL) is scarcely reported. Therefore, efficacy, acute and long-term toxic effects, and long-term QOL of CRT for advanced HSCC were evaluated,using retrospective study and post-treatment quality of life questionnaires. in a tertiary hospital setting. Analysis was performed of 73 patients that had been treated with CRT. Toxicity was rated using the CTCAE score list. QOL questionnaires EORTC QLQ-C30, QLQ-H&N35, and VHI were analyzed. The most common acute toxic effects were dysphagia and mucositis. Dysphagia and xerostomia remained problematic during long-term follow-up. After 3 years, the disease-specific survival was 41%, local disease control was 71%, and regional disease control was 97%. The results indicated that CRT for advanced HSCC is associated with high locoregional control and disease-specific survival. However, significant acute and long-term toxic effects occur, and organ preservation appears not necessarily equivalent to preservation of function and better QOL.

Keywords: Chemoradiation, Head and neck cancer, Hypopharyngeal carcinoma, Quality of life

Introduction

For many years, surgical resection followed by radiotherapy has been the standard treatment for advanced hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (HSCC) [1, 2]. However, since the early 1990s, chemoradiation (CRT) has become a valuable alternative treatment option [3, 4]. Due to organ preservation, it has been suggested that CRT is followed by a better long-term quality of life (QOL) than after total laryngectomy (TLE), with similar survival [3, 4].

Two strategies have been developed during the past decade: sequential (i.e., induction) chemotherapy followed by radiotherapy, and concurrent CRT. Superior results of concurrent administration compared with sequential CRT have been reported regarding locoregional control, disease-free survival, and overall survival rates in case of laryngeal cancer [5]. No randomized studies on this subject for HSCC have been performed. However, the meta-analysis of Pignon et al. [6] suggests that concomitant CRT in case of HSCC leads to improved survival compared with radiotherapy alone.

Boscolo-Rizzo et al. [7] described better QOL after CRT compared with TLE. On the other hand, several other studies reported similar QOL outcomes between these modalities [8, 9]. Moreover, growing evidence is pointing towards severe acute and long-term toxicity rates related to CRT, indicating that organ preservation is not necessarily equivalent to preservation of function and better QOL [10, 11].

In summary, a clear picture concerning long-term toxicity and QOL after CRT for head and neck cancer has not evolved yet. Hence, the best treatment modality to cure the cancer while minimizing adverse effects and toxicity in these patients remains subject to debate. Detailed reports of CRT specifically addressing HSCC are particularly scarce. The objectives of this study are to evaluate the efficacy, acute and long-term toxic effects, and long-term QOL of concurrent CRT as a primary treatment modality for advanced HSCC.

Methods

A total of 73 consecutive patients who received concurrent CRT for stage III-IV primary HSCC between January 2000 and January 2008 were included in this study. The study was approved by the institutional ethical review board of the Rotterdam Erasmus Medical Center. Medical records were reviewed for patient demographics, tumor site and stage, treatment, morbidity during and after treatment, and follow-up. Comorbidity was assessed using the Adult Comorbidity Evaluation 27 Index (ACE-27) [12].

All patients received radiotherapy, concurrent with chemotherapy starting on day 1 of radiotherapy. Radiotherapy was given for 43 days (median, range: 17–47 days). The radiation field encompassed the gross disease (primary tumor and/or nodal disease) with a 0.5 cm margin. In all patients, either 3-dimensional conformal (3DCRT) or “step and shot” intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) techniques were applied. Usually, 5–11 non-opposing, coplanar beams were chosen to ensure that at least 95% of the dose encompassed the target volume. Patients were completely treated according to an accelerated fractionation schedule. The intended radiation dose was 70 Gray (Gy) in 35 fractions of 2 Gy, given six times a week. The cumulative dose to the spinal cord was not to exceed 50 Gy. In those patients in whom parotid and submandibular glands sparing was feasible, the mean dose to at least one parotid gland was kept below 26 Gy. The mean dose to submandibular gland was kept below 39 Gy, when possible. Surface bolus was used for nodal disease with skin invasion or fungation. The chemotherapeutic regimen was two cycles of cisplatin 100 mg/m2 on day 1 and 22 of the treatment for the majority of the patients (77%). Eleven percent of the patients received four cycles of paclitaxel 60 mg/m2 once a week, and 8% received different chemotherapeutics due to a cardiovascular risk profile. In three patients (4%) 5FU/carboplatin instead of cisplatin was given due to pre-existent perceptive hearing loss.

Toxicity and morbidity were evaluated during treatment, as well as 3, 6, 12, and 24 months after treatment, using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 3.0 (CTCAE) [13]. In addition, weight loss, mode and duration of nutritional support, and renal function were evaluated before, during, and after treatment. Efficacy data included assessment of residual disease (defined as residual or new tumor within 3 months after the end of treatment) recurrent disease, disease-free survival and overall survival.

The Quality of Life Questionnaires EORTC QLQ-C30 (general cancer questionnaire, version 3.0) [14] and QLQ-H&N35 (specific Head and Neck module) [15] were sent to all patients that were alive at the time of analysis. In addition, the Voice Handicap Index (VHI) [16] was used to evaluate the psychosocial consequences of voice disorders. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 16.0. Paired data were analyzed using the paired t test. Non-parametric tests were performed using the Wilcoxon signed rank test and differences between percentages were calculated using the Chi-square test. Survival was calculated with the Kaplan–Meier method.

Results

Patient demographics, primary tumor site, and disease stage

Patient demographics, comorbidity, intoxications, and tumor characteristics are shown in Table 1. The ACE-classification was mainly determined by cardiovascular risk profile (37%), substance abuse (20%), and previous malignancies (14%). Prior to the start of therapy, 18% of the patients had lost more than 10% of their original body weight.

Table 1.

Patient demographics, co-morbidity, intoxications and tumor characteristics

| Characteristic | Value (%) |

|---|---|

| Total patients | 73 (100) |

| Gender | |

| Men | 61 (84) |

| Women | 12 (16) |

| Age (years) | |

| Median | 56 |

| Range | 43–78 |

| ACE-classification | |

| Grade 0 | 38 (52) |

| Grade 1 | 22 (30) |

| Grade 2 | 12 (17) |

| Grade 3 | 1 (1) |

| Weight loss before start of therapy (%) | |

| Grade 0: <5 | 43 (59) |

| Grade 1: 5–9 | 17 (23) |

| Grade 2: 10−20 | 10 (14) |

| Grade 3: >20 | 3 (4) |

| Smoking (cigarettes/day) | |

| <10 | 16 (22) |

| 10–25 | 21 (29) |

| >25 | 36 (49) |

| Alcohol (units/day) | |

| <6 | 34 (47) |

| 6–10 | 32 (44) |

| >10 | 7 (9) |

| Tumor site | |

| Piriform sinus | 60 (82) |

| Overlapping region | 5 (7) |

| Posterior wall | 4 (5.5) |

| Remaining | 4 (5.5) |

| TNM stage | |

| III | 11 (15) |

| IV | 62 (85) |

Acute toxicity

Three patients died during the treatment as a result of a myocardial infarction, pneumonia in a patient with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or sepsis thought to be the result of ulceration of the HSCC (2 days after the start of CRT, not related to the treatment), resulting in an overall mortality rate of 4% and a treatment-related mortality rate of 3%.

Treatment was completed according to protocol in 91% of the patients. Three previously mentioned patients (4%) died during treatment. In another 4% of the patients, the second chemotherapeutic cycle was postponed by 1 week due to renal insufficiency (n = 2) or pneumonia (n = 1). One patient (1%) received only one cycle of chemotherapy, due to an intermittent myocardial infarction. Unscheduled admissions during treatment were necessary in 27 patients (37%), mostly due to infection (15 patients) or dehydration (8 patients).

Prior to treatment, 36% of the patients had a serum creatinine level below normal (<65 μmol/L); the remaining 64% had values within normal limits. During treatment, the serum creatinine level increased from a mean of 67 μmol/L to 91 μmol/L (p < 0.000). Overall, 22% of the patients had >50% increase of the creatinine levels during treatment (13% had >100% increase).

All graded 3 or 4 adverse events that were monitored during treatment and after 3 and 6 months are displayed in Table 2. Dysphagia was the most severe acute and long-term adverse event that was reported. In 22% of the patients, nutritional support was maintained by either percutaneous gastrostomy (PRG) (n = 10) or nasogastric (n = 6) tube feeding prior to or at the start of the treatment due to severe weight loss, no standard prophylactic PRG or feeding tube placement was performed. During and after treatment, an additional 56% of the patients required PRG (n = 34) or nasogastric (n = 7) tube feeding due to dysphagia resulting in weight loss or dehydration. Nevertheless, during treatment, 45% of the patients lost 5–9% of their body weight (grade 1), and an additional 33% lost more than 10% (grade 2 or 3).

Table 2.

Percentage grade 3 and 4 acute toxicity

| Adverse event | During treatment (%) | After 3 months (%) | After 6 months (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 3 | Grade 4 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | |

| Dysphagia | 53 | 9 | 37 | 3 | 26 | 3 |

| Mucositis | 38 | 4 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Pain | 27 | 6 | 11 | 0 | 16 | 0 |

| Skin toxicity | 31 | 5 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Fatigue | 9 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| Nausea | 6 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Vomiting | 5 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dyspnea | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dry mouth | 6 | 0 | 14 | 0 | 10 | 2 |

| Ototoxicity | 6 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Long-term toxicity

During the first 3 months after therapy, 21 patients (30%) were admitted due to complications: dehydration (33.3%), intestinal infection (19%), dysphagia due to stenosis (19%), pneumonia (14.3%), or other complications (14.3%). Patients with stenosis presented with swallowing difficulties and were diagnosed on panendoscopy to exclude tumor recurrence. Between the fourth and second year after the treatment, most patients were admitted because of pharyngeal stenosis.

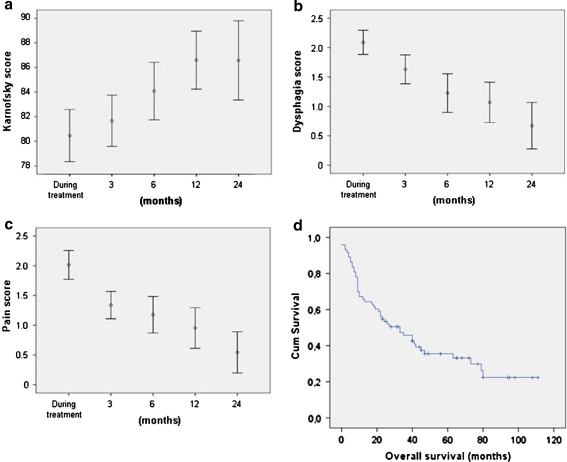

Overall performance was recorded with the Karnofsky index during treatment and follow-up, as illustrated in Fig. 1a. Significant increase of this score post-treatment (mean 87) compared with during treatment (mean 79) was seen after 12 months (p = 0.002).

Fig. 1.

Toxicity scores and survival during treatment and follow-up. The mean scores and 95% confidence interval (CI) of the Karnofsky score (a), dysphagia score (b), and pain score (c) are displayed. Overall cumulative survival (months) is shown in (d). Cum survival is cumulative survival

The percentage of graded 3 or 4 toxicity scores per adverse event are presented in Table 2. Although mucositis recovered mostly during the 6 months after treatment, long-term dysphagia remained significant. Six months after treatment, 26 and 3% still had grade 3 and 4 dysphagia, respectively (Fig. 1b). Despite tube feeding in 78% of the patients during and after treatment, 22% of the patients lost an additional 5–9% of their weight (grade 1), and 5% of the patients lost more than 10% (grade 2 or 3) in the first months following treatment. Overall, most acute toxicity resolved within a 3 months period. However, complaints of a grade 3 or 4 dry mouth increased. After 6 months, 16% of the patients still experienced grade 3 pain, but the mean CTC pain scores reduced to a 0.6 (grade 1) during the complete follow-up period (p = 0.005, Fig. 1c).

Residual disease, disease recurrence and survival

During follow-up, recurrent or residual disease was detected by means of MRI/CT-scan (58%), panendoscopy (35%), or physical evaluation (7%). Residual disease, (i.e., tumor recurrence within 3 months after therapy) was found in 16 patients (23%) of which three patients had local disease, resulting in a local disease control of 96% (67/70 patients) after 3 months. Eighty-one percent of patients with residual disease had regional metastasis (13 patients) confirmed by ultrasound-guided FNA, of which 11 patients were treated with salvage neck dissection. Hence, the regional disease control after 3 months including salvage surgery was 97% (68/70 patients).

In the period following the first 3 months after therapy, 28 patients developed tumor recurrence. The mean time between the end of therapy and recurrence of disease was 14 months (range 3–54 months). Of these patients, 17 patients had local, locoregional, or local and distant disease, resulting in a local disease control of 71% at a mean follow-up of 3 years. The Kaplan–Meier-Estimated cumulative 3-year survival corrected for tumor recurrence or residual disease was 42.1% (SD 6.1%).

Other patients with local recurrence were inoperable due to tumor extension, comorbidity, or distant metastasis. In addition, because three patients had regional recurrence of their disease in this period, the regional disease control after CRT and salvage neck dissection after 3 years was 93%. Furthermore, distant metastasis developed in nine patients, of which most patients (70%) had pulmonary metastasis. Other locations included costal, liver, or skin metastasis. A second primary tumor was found in the esophagus (n = 2) or lungs (n = 1).

The Kaplan–Meier curve for overall survival is shown in Fig. 1d. The median overall survival (calculated starting from the end of treatment) was 33 months (range 0–112 months). The 2 and 3-year survival rates were 56 and 38%, respectively. The disease-specific survival after 3 years was 41%.

Quality of life

The questionnaires were sent to all 24 patients who were alive at the time of the study. Twenty patients returned the completed questionnaires, resulting in a response rate of 83%. These patients were at least 2.5 years after treatment, with a mean of 5 years. The mean overall score for the Voice Handicap Index scale was 30.8 [±25.4 standard deviation (SD)], which is defined as mild-to-moderate voice handicap. The individual subscale scores revealed a mean (±SD; scale) functional score of 11.3 (9.8; mild-to-moderate), a physical score of 12.7 (9.9; mild), and an emotional score of 6.8 (7.2; mild). The results of the questionnaires are shown in Tables 3, 4, 5.

Table 3.

Quality of life questionnaire QLQ C-30

| Item | Mean score |

|---|---|

| Global health statusa | |

| Global health status | 67 |

| Functional scalesa | |

| Physical functioning | 75 |

| Role functioning | 55 |

| Emotional functioning | 73 |

| Cognitive functioning | 75 |

| Social functioning | 68 |

| Symptom scalesb | |

| Fatigue | 40 |

| Nausea and vomiting | 48 |

| Pain | 22 |

| Dyspnoea | 25 |

| Insomnia | 14 |

| Appetite loss | 33 |

| Constipation | 11 |

| Diarrhea | 5 |

| Financial difficulties | 16 |

a Higher scores correspond with higher quality

b Higher scores correspond with higher severity of symptoms

Table 4.

Quality of life questionnaire QLQ H&N35

| Item | Mean score |

|---|---|

| Symptom scales | |

| Pain | 16 |

| Swallowing | 34 |

| Senses problems | 34 |

| Speech problems | 31 |

| Trouble with social eating | 36 |

| Trouble with social contact | 14 |

| Less sexuality | 26 |

| Teeth | 26 |

| Opening mouth | 26 |

| Dry mouth | 39 |

| Sticky saliva | 51 |

| Coughing | 30 |

| Felt ill | 18 |

| Pain killers | 37 |

| Nutritional supplements | 47 |

| Feeding tube | 11 |

| Weight loss | 47 |

| Weight gain | 11 |

Higher scores correspond with higher severity of symptoms

Table 5.

Voice handicap index (VHI) score

| Overall VHI score | No. of patients (%) |

|---|---|

| Mild (0–30) | 10 (50) |

| Moderate (31–60) | 8 (40) |

| Severe (61–120) | 2 (10) |

Discussion

A total of 73 patients were treated with concurrent CRT. Three months after the treatment, local disease control was 96%, which gradually decreased to 71%, 3 years after the end of the treatment. In addition, regional control was very satisfying and durable, being 97 and 93% after 3 months and 3 years, respectively. This is comparable with most literature. HSCC consistently shows a trend for worse survival compared to laryngeal carcinoma [6, 17]. Unfortunately, most studies combine both groups in their analysis, making a comparison more difficult. In general, disease specific survival after 3 years of 41% is comparable with the literature [17–19].

Although synergy between chemotherapy and radiotherapy enhances the efficacy of the treatment [4–6], CRT is associated with high morbidity during treatment. Urba et al. [19] reported 79% of patients with any grade 3 or 4 toxicity treated with CRT for carcinoma in the hypopharynx or base of tongue. The significant treatment-related toxicity is also illustrated by 37% unscheduled admissions during treatment in our study. Even higher numbers have been described in other studies [17, 19], but this will in part be influenced by hospital policy and logistical issues. Nevertheless, this underlines the need for frequent patient monitoring during treatment and the early post-treatment period.

Overall, most moderate to severe toxic effects that occurred during treatment disappeared during the early post-treatment period. Mucositis is one of the most abundant acute toxic effects of CRT, and the 42% grade 3 or 4 rates in our study are comparable with most literature [17, 20]. As a result, tube feeding was required in 78% of the patients during treatment. Nevertheless, after 1 year, 12% of the patients still lost 5–9% of their body weight. This effect has previously been described by Hanna et al. [17] who reported weight loss of 5.4 kg after 1 year in patients with tube feeding, compared with 6.8 kg in patients without tube feeding.

Prior to treatment, 18% of the patients had already lost more than 10% of their original body weight. It has been shown that prophylactic gastrostomy tube placement could prevent weight loss and improve general condition during therapy [21]. However, it was also associated with significantly higher rates of late esophageal stricture formation and in some cases mortality. Corry et al. [22] compared the use of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tubes versus nasogastric tubes for enteral feeding during CRT. They concluded that the use of PEG tubes should be selective, because although PEG patients sustained significantly less weight loss at 6 weeks post-treatment, PEG tubes were also associated with frequent infections, higher overall costs, and more grade 3 dysphagia after 6 months than nasogastric tube patients.

In our population, 13% of the patients had a 100% creatinine level increase as a result of the toxic chemotherapeutic. Others have reported levels above normal limit up to 50% [20], stressing the need for close monitoring of renal function during CRT with cisplatin.

Most studies describe a mean Karnofsky score as inclusion criterion for treatment [9, 23]. In this study, the severity of acute and long-term toxic effects could also be illustrated by a decrease in Karnofsky score during treatment and prolonged recovery during the follow-up period. The mean Karnofsky score significantly recovered after 1 year (Fig. 1a), which is in line with other reports of long-term toxicity of CRT for advanced head and neck cancer [24, 25]. The mean score did not further increase after 2 years despite tumor control, which may be explained by new comorbidity or long-term toxicity. Long-term toxicity of CRT mainly consists of dry mouth and dysphagia [24, 25], which was confirmed by the QOL questionnaires, reporting functional scores of 39 and 34 for dry mouth and swallowing, respectively (Table 4). Although these are high numbers, similar rates have been described in other studies [8, 11, 17, 20]. Dyspgahia and xerostomia are serious complications of CRT resulting in medical, nutritional, and psychological problems and social distress [25]. They have a negative impact on the QOL of these patients due to associated difficulties in speech, chewing, swallowing, and potentially severe dental decay, especially in patients treated for laryngeal or hypopharyngeal lesions [25]. It has been reported that the amount of dysphagia has a significant correlation with the degree of xerostomia [26].

Forty-eight percent of our patient population had ACE score 1-3, indicating mild to severe comorbidity. Although this will most likely have influenced the complication and toxicity rates, the patient population was too diverse for univariate analysis, due to small group sizes.

Hanna et al. [8] reported QOL results using the EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-H&N35 of 19 patients that were treated with CRT for stage III–IV laryngeal cancer 15 months (average) prior to evaluation. Although the patients in the current study were on average 5 years after treatment, overall, the results of our study are similar or slightly better (Tables 3, 4). However, some interesting differences can be noted. In our study, less pain is reported, combined with higher use of painkillers (Fig. 1c). This may imply better pain control, but may also be due to lower numbers of neck dissections, which has been reported to be associated with arm and shoulder pain in 26% of the patients 2 years after surgery [11, 27]. Furthermore, less need for tube feeding is reported in the current study which corresponds with better swallowing function.

On the other hand, Boscolo-Rizzo et al. [7] reported superior results on virtually all categories of QOL-analysis in 28 patients that had been treated with CRT 24 months prior to evaluation. This indicates that large differences between QOL studies still exist, which is most likely explained by small group sizes. Nguyen et al. [11] performed a meta-analysis comparing five QOL studies of patients treated with CRT and concluded that dry mouth (70%) and dysphagia (50%) were the most common long-term side effects. However, these studies described results of different QOL questionnaires, making comparison between them difficult. Furthermore, the VHI results reflect mild or mild-to-moderate problems with speech rehabilitation in most patients. To our knowledge, no VHI results after CRT for HSCC have been reported previously. However, our results compare favorably to VHI results of patients 10 years after they had been treated with TLE [28].

The limitations of our retrospective series of CRT for advanced HSCC are inherent to all retrospective clinical study designs. These include, but are not limited to, selection bias of patients alive at time of the study and heterogeneity of patients. In addition, baseline QOL status prior to therapy is not reported, impeding conclusions on post-treatment QOL outcome. Due to these limitations, combined with the variable reported outcomes in the literature, we fully endorse efforts towards larger prospective clinical QOL trials reporting the use of standardized questionnaires, which would require a multi-center setting.

Future directions of CRT for advanced HSCC are pointing towards the use of new combinations of current therapeutic modalities. New strategies are being developed and tested, including postoperative CRT [29], induction chemotherapy followed by CRT [30], and peroperative gene therapy followed by CRT [31]. However, except from survival and local disease control, focus must also remain on reducing treatment-related toxicity and thereby improving acute and long-term QOL.

Conclusion

Chemoradiation as a primary treatment option for advanced HSCC is associated with high rates of local disease control and disease-specific survival. However, significant acute and long-term toxic effects occur, and organ preservation appears not necessarily equivalent to preservation of function. These effects have a long-lasting repercussion on the quality of life.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully thank Dr. M.H. Wieringa, epidemiologist, for her assistance in the statistical analysis of the data. M.M. Hakkesteegt, speech-language pathologist, is gratefully acknowledged for her comments on long-term quality of life after chemoradiation.

Conflict of interest

None

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Bova R, Goh R, Poulson M, Coman WB. Total pharyngolaryngectomy for squamous cell carcinoma of the hypopharynx: a review. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:864–869. doi: 10.1097/01.MLG.0000158348.38763.5D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keereweer S, de Wilt JH, Sewnaik A, Meeuwis CA, Tilanus HW, Kerrebijn JD (2010) Early and long-term morbidity after total laryngopharyngectomy. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 267(9):1437–1444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.[Anonymous] (1991) Induction chemotherapy plus radiation compared with surgery plus radiation in patients with advanced laryngeal cancer. The Department of Veterans Affairs Laryngeal Cancer Study Group. N Engl J Med 324: 1685–1690 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Lefebvre JL, Chevalier D, Luboinski B, Kirkpatrick A, Collette L, Sahmoud TLarynx. Preservation in pyriform sinus cancer: preliminary results of a European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer phase III trial. EORTC Head and Neck Cancer Cooperative Group. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996;88:890–899. doi: 10.1093/jnci/88.13.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forastiere AA, Goepfert H, Maor M, et al. Concurrent chemotherapy and radiotherapy for organ preservation in advanced laryngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2091–2098. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pignon JP, le Maître A, Maillard E, Bourhis J. MACH-NC Collaborative Group. Meta-analysis of chemotherapy in head and neck cancer (MACH-NC): an update on 93 randomised trials and 17,346 patients. Radiother Oncol. 2009;92(1):4–14. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boscolo-Rizzo P, Maronato F, Marchiori C, Gava A, Da Mosto MC. Long-term quality of life after total laryngectomy and postoperative radiotherapy versus concurrent chemoradiotherapy for laryngeal preservation. Laryngoscope. 2008;118:300–306. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e31815a9ed3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanna E, Sherman A, Cash D, et al. Quality of life for patients following total laryngectomy vs chemoradiation for laryngeal preservation. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:875–879. doi: 10.1001/archotol.130.7.875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trivedi NP, Swaminathan DK, Thankappan K, Chatni S, Kuriakose MA, Iyer S. Comparison of quality of life in advanced laryngeal cancer patients after concurrent chemoradiotherapy vs total laryngectomy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;139:702–707. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lambert L, Fortin B, Soulieres D, et al. Organ preservation with concurrent chemoradiation for advanced laryngeal cancer: are we succeeding? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76:398–402. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.01.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nguyen NP, Sallah S, Karlsson U, Antoine JE. Combined chemotherapy and radiation therapy for head and neck malignancies: quality of life issues. Cancer. 2002;94:1131–1141. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Piccirillo JF, Costas I. The impact of comorbidity on outcomes. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2004;66:180–185. doi: 10.1159/000079875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trotti A, Colevas AD, Setser A, et al. CTCAE v3.0: development of a comprehensive grading system for the adverse effects of cancer treatment. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2003;13:176–181. doi: 10.1016/S1053-4296(03)00031-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:365–376. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bjordal K, Hammerlid E, Ahlner-Elmqvist M, et al. Quality of life in head and neck cancer patients: validation of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire-H&N35. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1008–1019. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.3.1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacobson B, Johnson A, Grywalsky C, et al. The voice handicap index (VHI): development and validation. Am J Speech Language Pathol. 1997;6:66–70. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanna E, Alexiou M, Morgan J, et al. Intensive chemoradiotherapy as a primary treatment for organ preservation in patients with advanced cancer of the head and neck: efficacy, toxic effects, and limitations. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:861–867. doi: 10.1001/archotol.130.7.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tai SK, Yang MH, Wang LW, et al. Chemoradiotherapy laryngeal preservation for advanced hypopharyngeal cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2008;38:521–527. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyn073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Urba SG, Moon J, Giri PG, et al. Organ preservation for advanced resectable cancer of the base of tongue and hypopharynx: a Southwest Oncology Group Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:88–95. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vokes EE, Kies MS, Haraf DJ, et al. Concomitant chemoradiotherapy as primary therapy for locoregionally advanced head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:1652–1661. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.8.1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen AM, Li BQ, Lau DH, et al. Evaluating the role of prophylactic gastrostomy tube placement prior to definitive chemoradiotherapy for head and neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;78:1026–1032. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Corry J, Poon W, McPhee N, et al. Prospective study of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tubes versus nasogastric tubes for enteral feeding in patients with head and neck cancer undergoing (chemo)radiation. Head Neck. 2009;31:867–876. doi: 10.1002/hed.21044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pfister DG, Su YB, Kraus DH, et al. Concurrent cetuximab, cisplatin, and concomitant boost radiotherapy for locoregionally advanced, squamous cell head and neck cancer: a pilot phase II study of a new combined-modality paradigm. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1072–1078. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.00.1792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van der Molen L, Van Rossum MA, Burkhead LM, Smeele LE, Hilgers FJ. Functional outcomes and rehabilitation strategies in patients treated with chemoradiotherapy for advanced head and neck cancer: a systematic review. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;266(6):901–902. doi: 10.1007/s00405-008-0845-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Machtay M, Moughan J, Trotti A, et al. Factors associated with severe late toxicity after concurrent chemoradiation for locally advanced head and neck cancer: an RTOG analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(21):3582–3589. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Logemann JA, Smith CH, Pauloski BR, et al. Effects of xerostomia on perception and performance of swallow function. Head Neck. 2001;23:317–321. doi: 10.1002/hed.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chaplin JM, Morton RP. A prospective, longitudinal study of pain in head and neck cancer patients. Head Neck. 1999;21:531–537. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0347(199909)21:6<531::AID-HED6>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Evans E, Carding P, Drinnan M. The voice handicap index with post-laryngectomy male voices. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2009;44:575–586. doi: 10.1080/13682820902928729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Winquist E, Oliver T, Gilbert R. Postoperative chemoradiotherapy for advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Head Neck. 2007;29:38–46. doi: 10.1002/hed.20465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adelstein DJ, Moon J, Hanna E, et al. Docetaxel, cisplatin, and fluorouracil induction chemotherapy followed by accelerated fractionation/concomitant boost radiation and concurrent cisplatin in patients with advanced squamous cell head and neck cancer: a Southwest Oncology Group phase II trial (S0216) Head Neck. 2010;32:221–228. doi: 10.1002/hed.21179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoo GH, Moon J, LeBlanc M, et al. A phase 2 trial of surgery with perioperative INGN 201 (Ad5CMV-p53) gene therapy followed by chemoradiotherapy for advanced, resectable squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity, oropharynx, hypopharynx, and larynx: report of the Southwest Oncology Group. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;135:869–874. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2009.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]