Abstract

Background

Given that most addiction counselors enter the field unprepared to implement psychosocial evidence-based practices (EBPs), surprisingly little is known about the extent to which substance abuse treatment centers provide their counselors with formal training in these treatments. This study examines the extent of formal training that treatment centers provide their counselors in cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), motivational interviewing (MI), contingency management (CM), and brief strategic family therapy (BSFT).

Methods

Face-to-face interviews with 340 directors of a nationally representative sample of privately funded US substance abuse treatment centers.

Results

Although a substantial number of treatment centers provide their counselors with formal training in EBPs that they use with their clients, coverage is far from complete. For example, of those centers that use CBT, 34% do not provide their counselors with any formal training in CBT (either initially or annually), and 61% do not provide training in CBT that includes supervised training cases. Sizable training gaps exist for MI, CM, and BSFT as well.

Conclusions

The large training gaps found in this study give rise to concerns regarding the integrity with which CBT, MI, CM, and BSFT are being delivered by counselors in private US substance abuse treatment centers. Future research should examine the generalizability of our findings to other types of treatment centers (e.g., public) and to the implementation of other EBPs.

Keywords: dissemination, implementation, training, evidence-based practice

1. Introduction

Both in the US and in other nations, policymakers have strongly encouraged counselors to learn empirically supported mental health and addiction treatments to improve client care (Reickmann et al., 2009; Giuseppe and Clerici, 2006; Hintz and Mann, 2006; Miller et al., 2006). Training addiction counselors in the proficient use of psychosocial evidence-based practices (EBPs) is basic to ensuring the proper delivery of these treatments and improving client outcomes (Martino, 2010; Glasner-Edwards and Rawson, 2010). Inasmuch as most addiction counselors in the US are said to enter the field unprepared to implement EBPs (Weissman et al., 2006), the vast majority of EBP-related training typically occurs on the job, after counselors have completed their formal coursework for the profession (Kerwin et al., 2006).

A growing literature on successful training methods for addiction counselors has shown that, while workshops and self-study approaches may be useful for increasing counselor knowledge of EBPs, by themselves they have minimal influence on counselor behavior or ability to implement EBPs effectively. Rather, to improve counselors’ EBP implementation skills, numerous studies have shown that training needs to include competency-based supervision (i.e., supervised training cases), in which supervisors directly observe counselors’ sessions (via audiotape or videotape review) and then provide performance feedback and individualized coaching, guided by formal treatment integrity ratings (Beidas and Kendall, 2010; Herschell et al., 2010; Martino, 2010; and Rakovshik and McManus, 2010).

Although much has been written about the efficacy and effectiveness of various methods for training addiction counselors in EBPs, surprisingly little is known about the extent to which substance abuse treatment centers in the US actually provide such training for their counselors. To shed light on the prevalence of counselor training in several EBPs in US substance abuse treatment centers, this study uses data from the 2007–2008 wave of the National Treatment Center Study (NTCS), a dataset containing information on training activities from a nationally representative sample of 345 privately funded treatment centers in the US. The NTCS goes beyond prior studies that only surveyed a small number of directors and asked about broad EBP implementation rather than specific approaches (e.g., Zazzali et al., 2008). Directors of all centers were asked questions about the level and type of training they provide their counselors in several EBPs, including cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), contingency management (CM), motivational interviewing (MI), and brief strategic family therapy (BSFT). Answers to these questions have potentially important implications regarding the integrity of EBPs being delivered by treatment center addiction counselors to their clients.

CBT, MI, CM, and BSFT were chosen for inclusion in this study because they are all relatively recent and particularly prominent additions to the EBPs used in substance abuse treatment and thus should be linked with training (Miller et al., 2005). In addition, these treatments collectively address the multifaceted motivational, coping skill, and familial issues often involved in problems of addiction (Glasner-Edwards and Rawson, 2010). To our knowledge, this is the first study in the US or elsewhere to examine systematically the provision of counselor training by substance abuse treatment centers to support the implementation of EBPs.

2. Methods

2.1 Data

Data are taken from the fifth wave of the National Treatment Center Study, a nationally representative longitudinal study of privately funded substance abuse treatment centers. Data were collected via face-to-face interviews between February 2007 and July 2008 with clinical directors of 345 private-sector treatment centers. On average, interviews were approximately 2.5 hours in length. All field interviewers held at least a bachelor’s degree and, prior to conducting interviews on their own, received 20 hours of interview training, spent 10–20 hours reviewing the survey instrument, conducted three to five mock interviews, observed at least one interview, and conducted at least one training interview under the supervision of an experienced field interviewer.

Treatment centers were selected via a two-stage random sampling design. First, all US counties were assigned to 1 of 10 strata based on population and were then randomly sampled within strata. This process ensured inclusion of a mixture of urban, suburban, and rural areas. Second, using national and state directories, all substance abuse treatment facilities in the sampled counties were enumerated. Treatment centers were then proportionately sampled across strata, with telephone screening used to establish eligibility for the study. Facilities screened as ineligible were replaced by random selection of alternative treatment centers from the same geographic stratum. The final NTCS sample of 345 centers represented a 67% response rate. Five of the 345 centers were dropped in the present study due to insufficient data, resulting in a final study sample of 340 treatment centers. Table 1 presents summary statistics that describe the centers in this study.

Table 1.

Study Center Characteristicsa

| M (SD) or % (n) | |

|---|---|

| Structural variables | |

| Total counselors, M (SD) | 11.7 (14.1) |

| Accreditedb,% (n) | 56.5 (192) |

| Not-for-profit, % (n) | 63.1 (212) |

| Residential, % (n) | 27.4 (93) |

| Intensive outpatient (IOP), % (n) | 74.7 (254) |

| Outpatient (non-MM), % (n) | 70.6 (240) |

| Organizational values/norms | |

| 12-step orientationc, % (n) | 24.7 (84) |

| Research experienced, % (n) | 37.4 (129) |

| Counselor variables | |

| % Bachelor’s counselors, M (SD) | 29.1 (29.5) |

| % Master’s counselors, M (SD) | 47.6 (33.6) |

| % Certified SA counselors, M (SD) | 53.2 (33.9) |

| Patient variables | |

| % Women, M (SD) | 38.6 (19.6) |

| % Adolescents, M (SD) | 10.0 (20.8) |

| % Dually diagnosed, M (SD) | 49.9 (26.4) |

M = mean

SD = standard deviation

MM = methadone maintenance

SA = substance abuse

Study sample comprised N = 340 substance abuse treatment centers.

Accredited = 1 if accredited by either JCAHO or CARF; 0 otherwise.

12-step orientation = 1 if the treatment program was primarily based on 12-step model; 0 otherwise.

Research experience = 1 if during the past two years the center was involved in (a) any research

project that directly involved the clients in the center, or (b) any research initiative designed to help

improve the quality of addiction treatment and encourage the use of EBPs; 0 otherwise.

Treatment centers were defined as “private sector” if at least 50% of their annual operating revenues came from commercial insurance, patient fees, and income sources other than “block” funding such as government grants or contracts. Medicaid and Medicare, which are reimbursements from public dollars received by centers on an individual patient basis, were not regarded as “block” funding because they are not guaranteed sources of funding for centers (like government block grants and contracts) and thus are more similar in spirit to private sources of revenue – i.e., centers must seek and attract individual patients with Medicaid and Medicare.

The American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) considers addiction treatment as a continuum defined by the following five levels of care (Mee-Lee et al., 1996): early intervention services (Level 0.5), outpatient services (Level 1), intensive outpatient/partial hospitalization services (Level 2), residential/inpatient services (Level 3), and medically-managed intensive inpatient services (Level 4). To be eligible for the study, centers were required to offer alcohol and drug treatment at a level of intensity at least equivalent to ASAM Level 1 outpatient services. Eligibility requirements excluded counselors in private practice, halfway houses, and transitional living facilities; centers offering exclusively methadone maintenance, court-ordered driver education classes, or detoxification services; and centers located in correctional and Veterans Health Administration facilities. All research procedures, including a $100 donation to centers for participation, were approved by the University of Georgia’s Institutional Review Board.

The face-to-face interview approach offered advantages in assuring data quality. To help prepare for the interview, respondents were provided with a list of pre-interview questions. This allowed them to consult their records prior to the interview to ascertain, for example, the number of counselors who were provided formal training by the center in each of the EBPs used with clients. The interview included separate modules for CBT, MI, CM, and BSFT, including detailed follow-up questions that allowed the interviewer to check for internal consistency and validity of respondents’ answers. Inconsistent and/or invalid responses were clarified and reconciled in real-time by the interviewer. For example, directors who responded that their centers used CBT with clients were asked the extent to which the delivery of CBT in their centers emphasized (a) identification of “triggers” of substance use, (b) routine discussions of encounters with “high-risk” situations for substance use and the coping skills used in those situations, (c) use of role-playing in learning new skills, (d) assigning homework through which clients practice new skills, (e) reviewing homework in terms of what clients learned, (f) discussions of “craving” as normal, (g) development of concrete strategies for coping with craving, (g) learning drug refusal skills, (h) creating an “all-purpose coping plan” of emergency contacts, safe places, and reliable distracters, (i) learning how to recognize and interrupt “seemingly irrelevant decision” chains before relapse occurs, and (j) developing problem-solving skills. Similar detailed EBP-specific follow-up questions were asked for MI1, CM2, and BSFT.3

2.2 Survey questions and analyses

This study comprises three straightforward analyses that examine the provision of counselor training in addiction EBPs by substance abuse treatment centers. Whenever possible, the analyses were conducted in parallel on each of the four EBPs examined in this study: CBT, MI, CM, and BSFT. However, because the NTCS asked a truncated set of questions about training in CM, CM was excluded from several of the analyses below. In describing the specific survey questions (enclosed in quotation marks below) on which the study analyses are based, the phrase “the EBP” acts as a placeholder to represent CBT, MI, CM, and BSFT, as appropriate.

First, for CBT, MI and BSFT, we present the number of treatment centers that answered the following four primary questions affirmatively: (1) “Is the EBP currently used in this center?”, (2) “Does this center provide its counselors with formal training in the EBP (either in-house or off-site)?”, (3) “Does the training include supervised training cases?”, and (4) “Are training cases videotaped or audiotaped and then reviewed by a supervisor?”. We also present the number of treatment centers that (1) use CM with clients, and (2) provide their counselors with formal training in CM.

Second, for each of the four EBPs, we present the average percentage of counselors receiving formal training in that EBP since they began working at the treatment center (assuming the center provides formal training in that EBP). The percentage of counselors receiving training in a given EBP at a given center is calculated as the number of trained counselors divided by the total number of counselors employed at the center. For CBT, MI and BSFT, we also use t-tests to examine whether this percentage significantly differs according to whether there is a formal expectation by the center director (based on his or her beliefs of proficiency) that all counselors will develop proficiency in the use of the EBP. These analyses are based on the following questions: (1) “How many counselors (i.e., clinical staff who carry a patient caseload) are employed by the center?”, (2) “How many of your counselors have received formal training in the EBP since they began working at the center?”, and (3) “Is there a formal expectation that all counselors will develop proficiency in the use of the EBP?”.

Third, for CBT, MI and BSFT, we present (a) the average number of hours of training each counselor receives through the treatment center before they begin using the EBP with their clients, and (b) the average number of hours of ongoing training each counselor receives each year specifically to maintain their EBP skills. We also present the percentage of treatment centers that report providing “no set amount” of initial or ongoing training hours. These analyses are based on the subsample of centers that provide training in the given EBP and the following questions: (1) “How many hours of training does each counselor receive through this center before they begin using the EBP with their clients?”, and (2) “How many hours of ongoing training does each counselor receive each year specifically to maintain their skills in the EBP?”.

3. Results

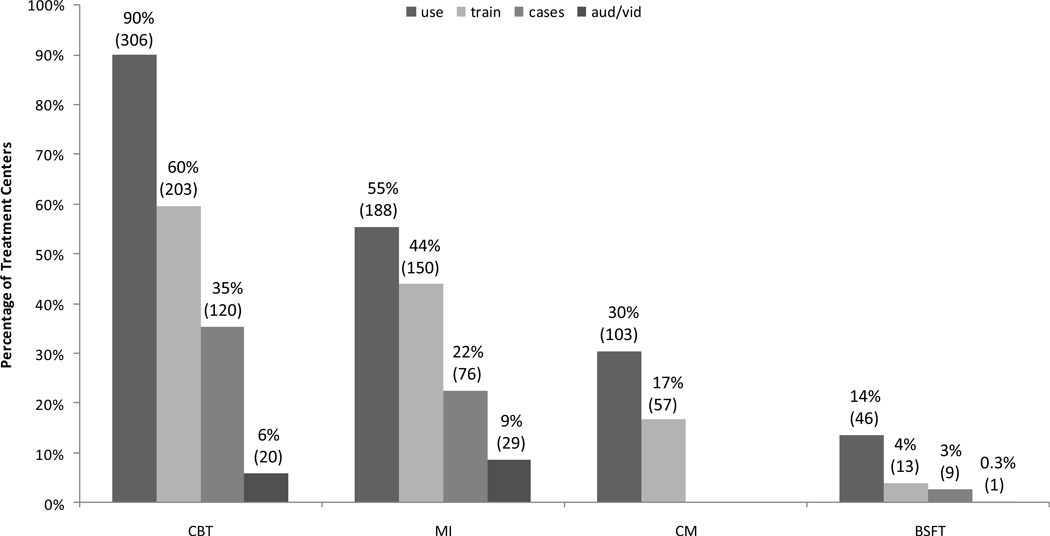

Figure 1 shows the percentage (and number) of treatment centers that answered ‘yes’ to the four primary questions described in section 2.2. For example, of the 340 centers in our study sample, 90%, 55%, 30%, and 14% use CBT, MI, CM, and BSFT, respectively, with clients. The percentage of centers that use exactly one, two, three, and four of the study EBPs with clients is 28%, 42%, 20%, and 4%, respectively (results not shown). Of those centers that use CBT, MI, CM, and BSFT with clients, 66% (203/306), 80% (150/188), 55% (57/103), and 28% (13/46), respectively, provide their counselors with formal training in the corresponding EBP (either in-house or off-site).

Figure 1a,b.

By EBP, the percentage (and number) of treatment centers that (a) currently use the EBP; (b) provide counselors with formal training in the EBP (either in-house or off-site); (c) include supervised training cases in the formal training; and (d) include training cases that are videotaped or audiotaped and then reviewed by a supervisor.

aStudy sample comprised N = 340 substance abuse treatment centers. Percentages (counts in parentheses) are the percentage (number) of centers that answered ‘yes’ to the following four questions: “Use” = Is the EBP currently used in this center?; “Train” = Does this center provide its counselors with formal training in the EBP (either in-house or off-site)?; “Cases” = Does the training include supervised training cases?; “Aud/Vid” = Are training cases videotaped or audiotaped and then reviewed by a supervisor?

bQuestions involving the use of supervised training cases were not asked for CM.

Of those centers that use CBT, MI, and BSFT with clients and provide their counselors with formal training in the corresponding EBP, 59% (120/203), 51% (76/150), and 69% (9/13), respectively, include supervised training cases as part of the training, and 17% (20/120), 38% (29/76), and 11% (1/9), respectively, of these centers include training cases that are audiotaped or videotaped and then reviewed by a supervisor. Said differently, of those centers that use CBT, MI and BSFT with clients, 39% (120/306), 40% (76/188), and 20% (9/46), respectively, provide their counselors with formal training in the corresponding EBP that includes supervised training cases, and 7% (20/306), 15% (29/188), and 2% (1/46), respectively, provide their counselors with formal training in the corresponding EBP that includes training cases that are audtiotaped or videotaped and then reviewed by a supervisor. As seen in Figure 1, a similar pattern of training provision exists across all four EBPs. In addition, the results in Figure 1 are consistent across treatment modalities (i.e., residential, outpatient, IOP; results not shown).

Column 2 (average percentage of counselors trained) of Table 2 shows that treatment centers provide an average of 49%–66% of their counselors with formal training in the various EBPs. Column 3 (percentage of centers that expect all counselors to be proficient) shows that a surprisingly large percentage of center directors report that they expect all of their counselors to be proficient in the EBPs. Columns 4 and 5 show that a substantially higher percentage of counselors receive formal training in treatment centers with directors that expect all of their counselors to be proficient in a given EBP compared to treatment centers with directors that do not have such high expectations. The lack of a statistically significant finding for BSFT in this regard is likely due to the small number of treatment centers that provide training in BSFT (n = 13).

Table 2.

Average Percentage of Counselors Trained – Overall and by Expectation that All Counselors will be Proficienta

| EBP | Average percentage of counselors trained M (SD) |

Percentage of centers that expect all counselors to be proficient % (SD) |

Average percentage of counselors trained in centers that expect all to be proficient M (SD) |

Average percentage of counselors trained in centers that do not expect all to be proficient M (SD) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBT (n=203) | 63.1 | 72.8 | 68.4 | 47.5 | <0.001 |

| (31.5) | (44.6) | (30.3) | (30.2) | ||

| MI (n=150) | 56.3 | 73.3 | 61.4 | 43.2 | 0.003 |

| (32.9) | (44.4) | (32.6) | (30.2) | ||

| CM (n=57) | 66.1 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| (34.5) | |||||

| BSFT (n=13) | 49.0 | 46.2 | 63.4 | 36.6 | 0.206 |

| (37.0) | (51.9) | (40.6) | (31.3) |

M = mean

SD = standard deviation

NA = not asked

Results are based on the subsample of centers that provide their counselors with formal training in the EBP.

Columns 2 and 4 of Table 3 show the average number of hours of initial training and ongoing annual training, respectively, that counselors receive in each of the EBPs, while columns 3 and 5 show the percentage of treatment centers that report providing “no set amount” of initial training hours or ongoing annual training hours, respectively. Given that Table 3 is based on the subsample of treatment centers that provide their counselors with formal training in the given EBPs, it is reasonable to assume that centers that report “no set amount” of training hours are actually providing some training, albeit an unknown amount.

Table 3.

Average Number of Hours of Initial and Annual Ongoing Training per Counselora

| Initial Training |

Annual Ongoing Training |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hours | No Set Amount | Hours | No Set Amount | |

| EBP | M (SD) | (%) | M (SD) | (%) |

| CBT (n=203) | 15.8 (18.0) | 67.0 | 14.8 (18.4) | 62.1 |

| (n=67) | (n=77) | |||

| MI (n=150) | 11.5 (13.6) | 38.7 | 6.8 (8.3) | 40.7 |

| (n=92) | (n=89) | |||

| BSFT (n=13) | 35.8 (27.0) | 30.8 | 24.8 (28.1) | 15.4 |

| (n=9) | (n=11) | |||

M = mean

SD = standard deviation

Results are based on the subsample of centers that provide their counselors with formal training in the EBP.

Although the NTCS did not ask about workshop training activities specifically, the comparatively large number of training hours provided counselors in BSFT is consistent with BSFT workshop intensity, up to 96 hours in total hours of training (Robbins et al., 2011), while workshops in CBT and MI typically last 1 to 3 days (Walters, et al., 2005). Across the EBPs, the average number of initial training hours that counselors receive before they begin using a given EBP with clients is greater than the average number of annual ongoing training hours that counselors receive to maintain their skills in the EBP.

4. Discussion

This study has several important findings. First, although a substantial number of substance abuse treatment centers provide their counselors with formal training in EBPs, the data indicate that many centers do not provide such training. For example, of those centers that use MI, CBT, CM, and BSFT with their clients, 20%, 34%, 45%, and 72%, respectively, do not provide their counselors with any formal training in the corresponding EBP. This includes training provided either in-house or off-site, as well as training provided either initially before counselors begin using the EBP with clients or annually to maintain existing EBP skills. The variation in this training gap across EBPs may be partly attributable to differences in the general availability of training resources across EBPs. For example, MI has a very well established and extensive training network across the US and internationally with MI trainers and translations in at least 38 languages (Miller and Rollnick, 2009), while more recent EBPs, such as BSFT, may not have as many training resources available to teach counselors these approaches. An even more surprising finding occurs among centers that indicate that their approach to quality management includes the expectation that all of their counselors should be proficient in the EBPs adopted for use by the centers. In these centers, approximately 1/3 of the counselors are not provided with any formal training in the corresponding EBPs, either initially or annually (see Table 2). This training gap may be partly attributable to administrators’ acceptance of counselors’ assertions about their skill levels relative to EBPs, which are likely overestimations (Carroll et al., 2010; Martino et al., 2009). It may also be partly attributable to a lag in training due to counselor turnover (i.e., at the time of the survey, some newly-hired counselors may not have received their training yet).

Second, experience with supervised training cases is a critical component of training strategies aimed at improving counselors’ skills in delivering EBPs (Beidas and Kendall, 2010; Herschell et al., 2010; Martino, 2010; Rakovshik and McManus, 2010). It is thus a concern that of those centers that use MI, CBT and BSFT with their clients, 60%, 61%, and 80%, respectively, do not provide training that includes supervised training cases, and in only a small minority of centers do the supervisors review audiotaped or videotaped sessions of the counselors’ use of MI (15%), CBT (7%), and BSFT (2%). Moreover, the average number of hours of initial and annual ongoing training provided to counselors in CBT, MI, and BSFT is consistent with or slightly less than the typical duration of workshops for each of these EBPs, suggesting that relatively little additional supervisory time may be devoted to these EBPs.

Third, of those centers that provide formal training in CBT, MI, and BSFT, 67%, 39%, and 31%, respectively, reported “no set amount” of initial training hours, while 62%, 41%, and 15%, respectively, reported “no set amount” of annual ongoing training hours. This finding indicates that a surprisingly large number of center directors are unaware, even approximately, of how much EBP-related training is provided by their centers. This raises a concern inasmuch as administrative planning and support for training are key features of most dissemination models for EBPs to be successfully implemented (Simpson and Flynn, 2007). As noted by Simpson (2011), administrative leadership pressures and expectations can influence the degree to which counselors attend training or supervision is provided to support implementation, especially when complex behavioral interventions require that training be extensive and multi-staged over time.

One area not directly assessed in this study is the integrity with which the EBPs are being implemented in the treatment centers. The findings of this study, however, were not encouraging in that few of the center directors reported that their supervisors reviewed audiotaped or videotaped sessions of the EBPs used by counselors. Given the positive bias of counselor self-reports about their EBP adherence (Carroll et al., 2010; Martino et al., 2009), without careful monitoring of performance that includes integrity rating, center directors will not know if counselors have used EBPs with sufficient proficiency. Moreover, the vast majority of treatment center counselors are not being provided with rating-based performance feedback and coaching, one of the few strategies that has been shown to improve counselor EBP performance (Miller et al., 2004; Sholomskas et al., 2005). Improving the quality of training strategies used to prepare addiction counselors to implement EBPs remains a challenge to the field (Martino, 2010). Indeed, given the large training gaps found in this study, one wonders about the actual content of the EBPs reported as being utilized by many treatment centers.

This study has several strengths. First, the findings are based on a large, nationally representative sample of private treatment centers. Second, the data were collected via face-to-face interviews with center directors. Third, there was a generally consistent pattern of results across all four EBPs examined in the study.

This study also has several limitations. First, our findings may not generalize to other types of treatment centers (e.g., public) or to psychosocial EBPs not included in this study (e.g., twelve-step facilitation). Second, although the data were collected via face-to-face interviews with center directors, they were not corroborated with center counselors. In addition, center director self-reports might be compromised to some extent by the directors being too far removed from the day-to-day clinical work to accurately know what treatments counselors actually are using within sessions. However, after determining whether centers used a given EBP, a series of detailed questions allowed interviewers to check for internal consistency of respondents’ answers and for real-time clarification and correction in the event of apparent discrepancies. Moreover, the training gaps found in this study persist in spite of the possible pressures faced by directors to present their centers in a positive light. Third, the NTCS data do not allow us to measure the quality of reported training or whether the training improved counselor skills or patient outcomes.

In spite of these limitations, our findings about the absence of formal training support the very real concern expressed by others that “EBPs might be used incorrectly or with insufficient integrity by clinicians who do not have relevant training and/or expertise to facilitate proper delivery of these interventions” (Glasner-Edwards and Rawson 2010). Moreover, treatment centers that do not provide their counselors with formal training in EBPs are potentially missing out on the benefits associated with these workforce development activities (e.g., increased job satisfaction among counselors, reduced counselor turnover rates) (Knudsen et al., 2008).

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the provision of counselor training in addiction EBPs by substance abuse treatment centers. There are several areas for future research, including: (1) examining the generalizability of our findings to other types of treatment centers and to other EBPs; (2) examining in more detail the specific types and patterns (i.e., sequencing and spacing) of training activities that take place in treatment centers, including identifying innovations in training strategies that go beyond the common set of practices currently used and studied, with the goal of identifying the active ingredients of training that result in the most efficient use of resources; (3) examining to what extent, if any, the observed training gaps might be due to an emerging assumption about placing responsibility on the counselors themselves for keeping their professional skills current; (4) examining the correspondence of center director and counselor reports of activities (which may vary), including independent verification of the occurrence of the center training activities (e.g., signed attendance sheets) to lend credence to the self-reported training activities that may be biased; and (5) examining the factors that explain or predict the observed training gaps.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge helpful comments received from two anonymous referees.

Role of Funding Source

This research and preparation of this report was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R01DA013110, R01DA023230, U10DA015831, P50DA009241, and R25DA026636. NIH had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Directors who responded that their centers used MI with clients were asked the extent to which the delivery of MI in their centers emphasized (a) assessing clients with regard to the five stages of change (precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, maintenance), (b) encouraging clients to evaluate how their behaviors are different from their goals and ideals, (c) allowing clients to compare the costs and benefits of continuing or stopping their substance abuse, (d) exploring the areas in which the client wants to achieve change, (e) avoiding the use of argumentation with clients, (f) expressing support for the client’s ability to succeed, and (g) encouraging clients to develop their own “change plan” with goals and plans for dealing with barriers to those goals.

Directors who responded that their centers used CM with clients were asked about which behaviors are incentivized (i.e., What behaviors earn the patient an incentive/voucher?), how incentives are distributed (i.e., Are rewards guaranteed, or is there an element of chance involved?), whether clients receive their incentive/voucher in one-on-one counseling sessions or in a group setting, whether the value of the incentive or voucher increases as patients have consecutive positive outcomes on the desired behavior, and the kinds of motivational incentives that are used (i.e., What do patients receive, or what can the vouchers be exchanged for?).

Directors who responded that their centers used BSFT with clients were asked the extent to which the delivery of BSFT in their centers emphasized (a) building therapeutic alliances with the adolescent as well as family members, (b) gaining the trust of family members as a foundation for the change process, (c) including the entire family in the treatment process, (d) assessing patterns of family communication and interaction that contribute to the adolescent’s drug use, (e) use of “behavioral contracting” to set clear ground rules for family interactions, (f) having family members directly speak to each other rather than recounting events to the therapist, (g) developing appropriate boundaries between family members that avoid enmeshment and reduce disagreement, (h) empowering parents to be the leaders of the family, and (i) reframing negativity expressed by the client and/or family members.

Contributors

Roman was the Principal Investigator for the NTCS grant. Abraham oversaw data collection and contributed to the study design. Martino provided research support and contributed to the study design. Olmstead contributed to the study design, conducted the analyses, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Beidas RS, Kendall PC. Training therapists in evidence-based practice: a critical review of studies from a systems-contextual perspective. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2010;17:1–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01187.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Martino S, Rounsaville BR. No train, no gain? Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2010;17:36–40. [Google Scholar]

- Giuseppe C, Clerici M. Dual diagnosis—policy and practice in Italy. Am. J. Addict. 2006;15:125–130. doi: 10.1080/10550490500528340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasner-Edwards S, Rawson R. Evidence-based practices in addiction treatment: review and recommendations for public policy. Health Policy. 2010;97:93–104. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herschell AD, Kolko DJ, Baumann BL, Davis AC. The role of therapist training in the implementation of psychosocial treatments: a review and critique with recommendations. Clin. Psy. Rev. 2010;30:448–466. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hintz T, Mann K. Co-occurring disorders: policy and practice in Germany. Am. J. Addict. 2006;5:261–267. doi: 10.1080/10550490600754275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerwin ME, Walker-Smith K, Kirby KC. Comparative analysis of state requirements for the training of substance abuse and mental health counselors. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2006;30:173–181. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen HK, Ducharme LJ, Roman PM. Clinical supervision, emotional exhaustion, and turnover intention: a study of substance abuse treatment counselors in the Clinical Trials Network of the National Institute on Drug Abuse. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2008;35:387–395. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martino S. Strategies for training counselors in evidence-based treatments. Addict. Sci. Clin. Pract. 2010;5:30–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martino S, Ball SA, Nich C, Frankforter TL, Carroll KM. Correspondence of motivational enhancement treatment integrity ratings among therapists, supervisors, and observers. Psychother. Res. 2009;19:181–193. doi: 10.1080/10503300802688460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mee-Lee DL, Gartner L, Miller MM, Schulman GD, Wilford BB. Patient Placement Criteria for the Treatment of Substance-Related Disorders. Chevy Chase, MD: American Society of Addiction Medicine; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Ten things that motivational interviewing is not. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 2009;37:129–140. doi: 10.1017/S1352465809005128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Sorensen JL, Selzer JA, Brigham GS. Disseminating evidence-based practices in substance abuse treatment: a review with suggestions. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2006;31:25–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Yahne CE, Moyers TE, Martinez J, Pirritano M. A randomized trial of methods to help therapists learn motivational interviewing. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2004;72:1050–1062. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Zweben JZ, Johnson WR. Evidence-based treatment: why, what, where, when, and how? J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2005;29:267–276. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakovshik S, McManus G. Establishing evidence-based training in cognitive behavioral therapy: a review of current empirical findings and theoretical guidance. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2010;30:496–516. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reickmann TR, Kovas AE, Fussell HE, Stettler NM. Implementation of evidence-based practices for treatment of alcohol and drug disorders: the role of the state authority. J. Behav. Health Ser. Res. 2009;36:407–419. doi: 10.1007/s11414-008-9122-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins MS, Feaster DJ, Horigian VE, Puccinelli MJ, Henderson C, Szapocznik J. Therapist adherence in Brief Strategic Family Therapy for adolescent drug abusers. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2011;79:42–53. doi: 10.1037/a0022146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sholomskas DE, Syracuse-Siewert G, Rounsaville BJ, Ball SA, Nuro KF, Carroll KM. We don't train in vain: a dissemination trial of three strategies of training clinicians in cognitive behavioral therapy. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2005;73:106–115. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.1.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson DD. A framework for implementing sustainable oral health promotion interventions. J. Public Health Dent. 2011;71 Suppl. 1:S84–S94. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2011.00234.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson DD, Flynn PM. Moving innovations into treatment: a stage-based approach to program change. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2007;33:111–120. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters ST, Matson SA, Baer JS, Ziedonis DM. Effectiveness of workshop training for psychosocial addiction treatments: a systematic review. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2005;29:283–293. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Verdeli H, Gameroff MJ, Bledsoe SE, Betts K, Mufson L, Fitterling H, Wickramaratne P. National survey of psychotherapy training in psychiatry, psychology, and social work. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2006;63:925–934. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.8.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zazzali J, Sherbourne C, Hoagwood K, Greene D, Bigley M, Sexton T. The adoption and implementation of an evidence based practice in child and family mental health service organizations: a pilot study of functional family therapy in New York State. Adm. Policy Ment. Health. 2008;35:38–49. doi: 10.1007/s10488-007-0145-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]