Abstract

A survey was distributed nationwide to parents of deaf and hard of hearing children to inquire about their knowledge, acquisition and use of hearing rehabilitation services and related hearing aid care technologies. Two hundred and fifty-seven surveys were returned. The data revealed that parents with moderate to high incomes, regardless of their race or ethnicity, tend to have broader knowledge of the nature of hearing rehabilitation services, and acquire such services and hearing technologies at a rate greater than that of parents with lower incomes. The unavailability of hearing health care services in minority communities and high costs associated with hearing aids and cochlear implants were reported as the major reasons why disparities exist, particularly, among minorities.

Keywords: minority health disparity, hearing health care, hearing impaired children, minority parents

INTRODUCTION

The acquisition and use of hearing aids and participation in auditory rehabilitation therapy are the treatment recommendations for more than 80% of identified hearing loss cases found in the U.S. (National Council on the Aging, 1999). Yet, less than 40% of the estimated 32 million Americans with significant hearing disability avail themselves of these treatments (Kochkin, 2005). Moreover, the use of hearing aids and hearing rehabilitation services by racial and ethnic minority Americans, specifically, African Americans, has been estimated at less than 5% (Jones, 1987; Bazargan et al, 2001). The relatively high costs associated with hearing health products and the unavailability of hearing health care services in racial and ethnic minority communities have been given as explanations (Jones & Richardson, 1994).

Disparity in the acquisition and use of cochlear implants (CI) among minorities has also been reported. Data show that the ‘‘relative rate’’ of implantation by Anglo/Euro American children is five times higher than children of Hispanic origin, and 10 times higher than African American children. In a statistically equivalent comparison group study (Hyde & Power, 2005), 56% of children who wore conventional hearing aids were Anglo/Euro American, whereas in the implanted group 83% of the children were Anglo/Euro American. For children of Hispanic American origin, 21% wore conventional hearing aids and 8% had implants. Among African American children, 16% wore conventional hearing aids and 5% were implanted, and for children of Asian American origin 3% had conventional hearing aids and 2% had implants. Data for Native American children and children of multiracial or multiethnic backgrounds were not reported.

General Healthcare Disparities

A report by a committee of the Institute of Medicine (2002) reviewed over 100 studies that assessed the quality of healthcare for various racial and ethnic minority groups. The findings indicated that a significant variation in the rates of medical procedures exists by race, even when insurance status, income, age, and severity of conditions are comparable. The research indicates that U.S. racial and ethnic minorities are less likely to receive even routine medical procedures and experience a lower quality of health services. The Institute of Medicine committee recommended increasing awareness about disparities among the general public, health care providers, insurance companies, and policy-makers to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in healthcare. The report specifically stated, “Consistency and equity of care also should be promoted through the use of ‘evidence-based’ guidelines to help providers and health planners make decisions about which procedures to order or pay for based on the best available science (Institute of Medicine, 2002, p.1). The report also concluded that more minority health care providers are needed, especially since they are more likely to serve in minority and medically underserved communities.

The U.S. Census Bureau statistics on individuals living below the poverty level is also an important measure on the well-being of racial and ethnic minority groups. Racial and ethnic minorities are more likely than non-Hispanic whites to be poor or near poor. In 2002, the poverty rate for the U.S. population was 12.1%, up from 11.7% in 2001. The poverty rate was even higher for racial and ethnic minorities: Blacks (24%), Hispanics (22%), and 16.6% for foreign born populations (Proctor & Dalaker, 2002). “In general, racial and ethnic minorities often experience worse access to care due to lower quality of preventative, primary and specialty care.”(National Healthcare Disparities Report, 2004). Hispanic and African Americans had poorer quality of care than non-Hispanic Whites for about 40–60% of the quality measures including: access to health care, not receiving prenatal care, immunizations, lack of health insurance, and problems getting referrals to a specialist.

Hearing loss and disparity

It can be assumed that hearing health care disparities for racial and ethnic populations result in delayed identification and intervention for hearing loss and other communication disorders. This is a particularly critical issue for populations that have a higher incidence for hearing disorders. American Indian and Alaskan native infants, for example, have higher otitis media and associated outpatient and hospitalization rates than those for the general U.S. population of children (Curns, 2002). Alaskan Eskimos, African American and Hispanic children have been disproportionately represented in the categories of pre-maturity and meningitis. African American children have also higher rates of cytomegalovirus (Van Naarden et al., 1999; Scott, 2002) and lead poisoning. According to the 2003–2004 Gallaudet Research Institute’s national demographic survey on deaf and hard of hearing youth, of the 38,149 respondents, almost half (48.5%) of the deaf and hard of hearing children were from a racial or ethnic minority group.

Significance of this project

When disparities in the acquisition of therapeutic or rehabilitative services and in the utilization of viable health care technologies have been identified, like those related here to hearing rehabilitation health care, it is critical for researchers, practitioners, policy makers, and others to determine why those disparities persist; particularly in advance of any new approaches or new technologies being introduced. This investigation attempted to identify factors that might account for the reported disparity in the acquisition of information and the utilization of hearing rehabilitative services and related healthcare technologies, particularly, by racial and ethnic minority U.S. populations. Targeted specifically were African American parents of deaf and hard of hearing children.

METHOD

This research was conducted as part of a larger federally funded initiative focusing on minority health care disparity issues. A descriptive research approach was used, wherein a survey was developed to address a series of focused research questions pertaining to the information parents of deaf and hard of hearing children have regarding hearing rehabilitation services and related hearing health care technologies (e.g., hearing aids, cochlear implants, assistive devices, etc.). The primary research questions were as follow:

In what way do parents of deaf and hard of hearing children differ on the types of information they receive or have regarding hearing rehabilitation and hearing health care technologies?

Is there disparity in the acquisition of information and use of hearing rehabilitation services and related technologies across different racial and ethnic groups?

What factors account for the reported underutilization of hearing health rehabilitation services and related technologies among racial and ethnic minorities?

Survey Instrument

A thirty-six question/statement survey was developed that opened with a letter to parents explaining the purpose of the survey and asking their participation in the study. A statement was also provided guaranteeing the anonymity of their individual responses. The survey had three sections which included: Section 1 - questions asking for demographic information, including child’s age, race/ethnicity, hearing aid status, geographic location (city, state), and income status of the survey respondent; Section 2 - statements addressing parents’ knowledge of and experiences with managing their child’s hearing disability (e.g., seeking aural rehabilitation services, disposition regarding communication methods, causes of hearing loss, deaf culture, etc.); and Section 3 - statements pertaining to the acquisition, utilization, availability, and costs of hearing healthcare services and prosthetic technologies. The survey response format for Section 1 included simple yes-no or fill-in answers. The response format for Sections 2 and 3 required parents to indicate their level of agreement with statements. The choices were: strongly agree, agree, uncertain, disagree, or strongly disagree. A copy of the survey is posted in the Appendix.

Participants

Parent-members of the American Society for Deaf Children (ASDC) were targeted, initially, for exclusive participation in the study. The American Society for Deaf Children (http://www.deafchildren.org) was selected because it is advertised as a national organization with parents, therapists, and educators as members who are dedicated to the promotion of communication access and rehabilitation services for deaf and hard of hearing children. It was also reported to have a broad racial and ethnically diverse membership base (ASDC Secretary, personal communication, June 20, 2007). After review and approval by the ASDC Board of Directors, the survey was mailed to five-hundred parent members randomly selected from the organization’s 2007 mailing list. Parents were offered a small financial incentive to return their fully completed surveys by a specified date.

Although the initial survey response rate (30%) was deemed acceptable, there was a disappointingly low response from self-identified racial or ethnic minority parents, specifically, African American parents (<.03%). In that African American families had been the targeted population for the study, it was decided to redistribute the survey through another mailing to a second cohort of parents. Targeted were parents who were not members of ASDC but with deaf and/or hard of hearing children enrolled in urban school districts known (to this investigator) to have proportionally high numbers of African American students. The response from this second cohort was 50%.

RESULTS

Parent characteristics

Seven hundred and fifty surveys were distributed nationwide to the parents and/or guardians of deaf and hard of hearing children. A total of 257 or 34.4% of the surveys were satisfactorily completed, returned, and used for analysis. The data were aggregated according to parent’s income and racial or ethnic group membership. These data were analyzed, but only in terms of the number and percentage of responses to each question/statement in the survey. One hundred percent of the respondents completed questions that specifically asked about family income and parent/child race or ethnic identity. Questions about the gender of the parent/guardian responding, their age, marital status, their educational background, occupations, and their hearing status were omitted from the survey. This was to avoid an over-intrusive tone to the questioning and to entice an expedient response.

The majority of the respondents were Anglo/Euro American (73.9%), with 12.8% African-American, 7.4% Latino, 3.9% Asian, .39% Native American, and 1.5% other (assumed to be multiracial or multiethnic). The comparatively high percentage of African-American responses, which is comparable to that group’s representation in the current U.S. Population (U.S. Census Bureau, 2007) was understood to be a direct result of “oversampling” that population in the redistribution of the survey. It should be noted that the Latino/Latina Hispanic population, currently the largest ethnic minority population in the country (U.S. Census Bureau, 2007), as well as other ethnic minority populations were underrepresented in this sampling. Regarding geographic distribution of the survey respondents, 33 states across the country were represented. Parents who participated as part of the 2nd cohort had deaf and hard of hearing children enrolled in public school programs in small cities located along the Mid-Atlantic coastline (e.g., Virginia, Maryland, Delaware).

Table 1 shows the racial composition of the two cohorts of parent respondents. Cohort #1 consisted of 145 parent-members of ASDC. Cohort #2 consisted of 112 parents whose responses were solicited in the redistribution of the survey. The parents in Cohort #2 were not members of ASDC, and have or had deaf and hard of hearing children enrolled in public school programs in cities located along the mid-Atlantic coast. These data were sorted according to race or ethnic groups.

TABLE 1.

Two cohorts of parent respondents according race or ethnicity

| Race/Ethnicity | Number Cohort #1 | # 2 | (Total) | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White/Anglo/Euro American | 119 | 71 | (190) | 73.9% |

| Black/African American | 4 | 29 | (33) | 12.8% |

| Latino/Latina/Hispanic | 11 | 8 | (19) | 7.4% |

| Asian American | 10 | 0 | (10) | 3.9% |

| Native American | 1 | 0 | (1) | 0.39% |

| Other (multiracial/ethnic) | 0 | 4 | (4) | 1.5% |

| TOTAL | 145 | 112 | (257) | 99.89% |

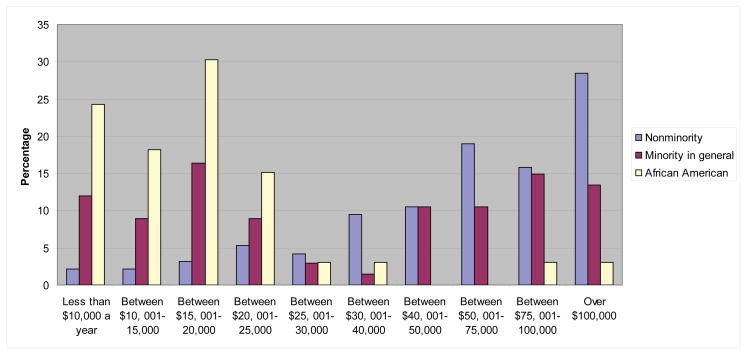

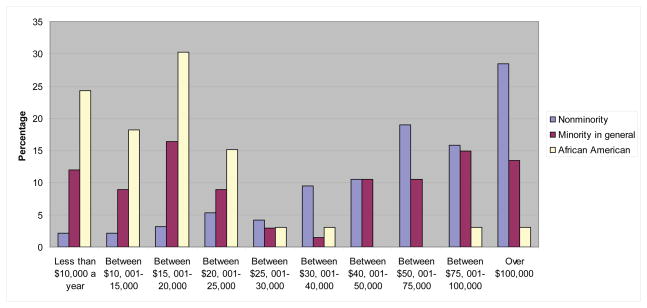

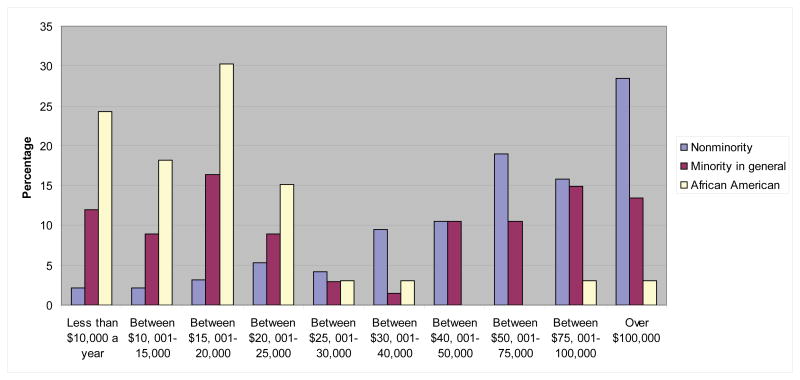

Figure 1 shows a composite for incomes for all parents (Cohort #1 and Cohort #2) according to non-minority minority in general and African American status.

FIGURE 1.

All respondents incomes according to their majority/minority/African American status

Child characteristics

Although the race or ethnicity of the children was presumed to be the same as their parents, one of the survey questions did ask parents to identify the race or ethnicity of their child. Table 2 shows the distribution of children according to their race/ethnicity. Note the number of children (263) exceeds the number of parent respondents (257). Apparently, there were more than one deaf or hard of hearing child in some families.

TABLE 2.

Race/Ethnicity distribution of deaf or hard of hearing children

| Race/Ethnicity | N | Percentage Distribution |

|---|---|---|

| White/Anglo/Euro Amer | 194 | 73.7% |

| Black/African American | 33 | 12.5% |

| Latino/Latina/Hispanic | 19 | 7.2% |

| Asian American | 8 | 3% |

| Native American | 1 | 0.38% |

| Multiracial/multiethnic | 8 | 3.04% |

| Total | 263 |

In addition to identifying their child’s race or ethnicity, parents were asked to identify their child’s age (see Table 3 below), as well as the degree or level of their child’s hearing loss. The majority of parents (48.9%) reported their children with having severe hearing losses. Profound losses were reported by 42.1% of parents and 8.9% of parents reported their children with moderately-severe hearing losses. No children were reported with having a mild hearing loss. Figure 2 shows the distribution for degree of hearing loss according to nonminority and minority group status. Some minor variability in the level of hearing loss across racial/ethnic groups was noted.

TABLE 3.

Number, ages and age range of children according to race or ethnicity

| Race/Ethnicity | Anglo/Euro American | Latino/Latina Hispanic | Asian American | African American | Native American | Multiracial/Multiethnic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 194 | 19 | 8 | 33 | 1 | 8 |

| Average age | 14.7 | 9.3 | 14.4 | 9 | 19 | 14.7 |

| Age Range | 1–24 | 1–18 | 8–24 | 2–17 | 19 | 1–19 |

FIGURE 2.

Percentage distribution of children’s hearing loss according to severity

Approximately two-thirds of the parents (65.5%) reported that the cause of their child’s hearing loss was unknown. The other third (34.4%) of the respondents reported meningitis, prematurity, birth trauma and maternal rubella as possible causes.

Parents were also asked to identify whether their child wore conventional hearing aids, cochlear implant(s), or no amplification at all. Table 4 shows the number of cochlear implants, conventional hearing aids or no amplification worn by children (N=263) according to their race or ethnicity. Figure 3 shows the percentage distribution of all children reported in this survey to be using either cochlear implants, conventional hearing aids, or no amplification according to their race/ethnicity.

TABLE 4.

number of cochlear implants, conventional hearing aids or no amplification worn by children (N=263) according to their race or ethnicity

| Race/Ethnicity | Anglo/Euro American | Latino/Latina Hispanic | Asian American | African American | Native American | Multiracial/Multiethnic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cochlear Implant | 51 | 7 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Conventional aids | 94 | 6 | 2 | 10 | 1 | 3 |

| No amplification | 48 | 8 | 3 | 21 | 0 | 2 |

| TOTAL | 193 | 21 | 9 | 33 | 1 | 6 |

FIGURE 3.

Percentage of children using cochlear implants and conventional hearing aids worn by children according to their race/ethnicity

With regards to the categorical use of cochlear implants, conventional hearing aids or no amplification, a total of 65 children (24.7%) were identified with wearing cochlear implants. Although the majority of the respondents in the survey were Anglo/Euro American, Latino/Latina/Hispanic American parents reported the highest percentage (26.3%) of their children fitted with cochlear implants. Anglo/Euro American children were next with 25.3%. African American children were reported with only 6.06% receiving cochlear implants. Given the very small sample size for Asian American children, Native Americans, and multiracial or multiethnic children, a percentage calculation for cochlear implant use was not calculated.

A total of 116 children (44.1%) were reported wearing conventional hearing aids (i.e., body level, BTE, ITE). Of the Anglo/Euro American children not wearing cochlear implants. 100% were reported wearing some type of conventional personal hearing aid. Of the Latino/Hispanic children not wearing cochlear implants, 66.6% wore conventional personal hearing aids leaving 1/3rd reported to be without personal amplification. As for the African-American children not wearing cochlear implants, 34.4% were reported with using conventional hearing aids, leaving approximately 2/3rd without use of personal amplification.

Regarding mode of communication used at home, the vast majority (93.8%) of parents reported using speech almost exclusively. Another question in the survey, however, revealed that two-thirds of the parents reported using total communication (a combination of speech, cued speech, gestures and sign language). Only 6.2 % of parents reported using American Sign Language (ASL) with their children.

Responses to Survey Questions

The response data from Section 2 and Section 3 of the survey were aggregated according to nonminority, minority-in-general and African-American groups. These data were also aggregated according to two income groups determined by a calculated median value (e.g., Incomes >$40,000, Incomes <$40,000). For ease of reporting, the combined percentages for only the affirmative responses (i.e., “Strongly Agree” and “Agree”) are presented. Although none of these data were analyzed, statistically, asterisks are used to identify percentages that appear to be “notably” divergent Tables 5–8 show these results.

TABLE 5.

Combined “Strongly Agree” and “Agree” responses to survey questions about parent experiences according to race and ethnicity classification

| Since considering a hearing aid or cochlear implant for our child we have learned that… | Nonminorities | Minorities in general | African- Americans |

|---|---|---|---|

| …hearing aids/cochlear implants work with everyone who wears one | 11.57 | 0 | 0 |

| …auditory rehabilitation following hearing aid fitting or implantation is as important as the technology itself | 83.68* | 29.85 | 30.30 |

| …our child can now hear perfectly | 4.21 | 0 | 0 |

| …our child wants to wear the hearing aid or implant all the time | 28.94* | 0 | 0 |

TABLE 8.

Combined “Strongly Agree” and “Agree” responses to survey questions about parent use and acquisition of technologies according to race and ethnicity classification.

| The hearing health care services and related technologies with which I am familiar … | Nonminorities | Minorities in general | African- Americans |

|---|---|---|---|

| …are too expensive | 52.6%* | 89.9% | 92.7% |

| …are not conveniently located in my community | .52%* | 86.5% | 78.7% |

| …do not have service providers who are representative of my social/cultural background | 0* | 94.02 | 96.96 |

| …do not use informational materials (i.e. brochures, pamphlets, etc.) that I can easily understand. | 14.73 | 34.32 | 42.42* |

| …do not have service providers who can relate to my individual hearing health care needs. | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| …are not decorated in a manner that is pleasing to me. | 11.05 | 0 | 0 |

| …have service providers who are unfriendly and intimidating | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| …have service providers who expect me to do all the work | 1.05* | 31.34 | 30.30 |

| …have service providers who are not competent to provide services to persons with my racial and ethnic background | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| …have service providers who do not communicate with me in a way I can easily understand. | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| …do not provide timely services, forcing me to wait. | 9.47 | 0 | 0 |

Parent Knowledge/Experience

Income data aggregated according to nonminority, minority in-general and African American groups were also analyzed and interpreted. The summary of these data are presented in the narrative that follows.

DISCUSSION

Parent Knowledge/Experiences

The results of the survey revealed several notable differences between parent groups with respect to their experiences, knowledge (information obtained), as well as their acquisition and use of hearing rehabilitation services and related technologies. When the parent responses were aggregated according to non-minority, minority-in-general, and African-American group status, it was discovered that approximately 2/3rds of the African American deaf or hard of hearing children, not fitted with cochlear implants, were also not wearing any type of personal amplification. This is in comparison to 1/3rd of Hispanic American children, and in stark contrast to Anglo/Euro American children; none of whom were without a cochlear implant or personal hearing aids. These data are consistent with the findings of Hyde & Power (2005), which showed a five to ten 10 fold difference, respectively, in the use of amplification and cochlear implants by Hispanic American and African American children compared to Anglo/Euro American children. It is important to note that severity of hearing loss associated with use, based on derived benefit from amplification, are factors that could easily explain why profoundly deaf or even severely hearing impaired individuals might choose not to use prescribed hearing aids. However, the data provided here regarding the levels of hearing loss for each group, showed comparable representation for all hearing loss levels. This would preclude the idea that one particular group of children (e.g., African American) had more severe losses than another group and therefore would be inclined not to use or need to use amplification. In point of fact, African American and Hispanic American children in this sample had quite similar levels of hearing loss represented as did Anglo/Euro American children, yet the use of personal amplification by minority children, in general, was substantially less than that of the Anglo/Euro American children.

Regarding information or knowledge parents acquired about hearing rehabilitation and hearing health care technologies (i.e., hearing aids, cochlear implants, classroom amplification systems) after being told their child was hearing impaired; over 80% of non-minority parents either strongly agreed or agreed that they learned that auditory rehabilitation …is as important as the technology itself. This response was in contrast to 29% and 30%, respectively, of the minority parents in general, and African American parents who either strongly agreed or agreed with the statement. It might be surmised that only those parents whose children had or were actively participating in aural rehabilitation, having been fitted with hearing aids or cochlear implants, would be in a position to accurately judge the importance of those services. Those not participating would not likely be in a position to make any positive judgments, nor be inclined to do so. Similar disparate responses were reported to statements relating to information and knowledge received on the different methods of communication used with deaf and hard of hearing children (e.g., total communication, cued speech, text messaging, etc.). Jones & Kretchmer noted in their 1988 investigation of the attitudes and knowledge of Black parents of deaf children, that conventional models for parent education about hearing rehabilitation, hearing aids, communication methods, etc., were possibly ineffective in teaching culturally different and/or low-income families, and new models were needed.

There also appeared to be a substantial difference in parents’ response to statements about the acquisition of knowledge for educational and vocational opportunities for deaf and hard of hearing children. Approximately 97 % of the non-minority parents indicated agreement with the statement that they learned something about vocational opportunities for their children after being told of their child’s hearing loss. Just 53% of minority parents in general and only 27% of African American parents responded affirmatively to this question.

The responses of non-minority, minority in general and African American parents were in far greater agreement with respect to statements relating to knowledge gained about the causes of hearing loss. Responses were again divergent, though, regarding parents’ knowledge about Deaf culture. Approximately 58% of non-minority parents agreed to having learned something about deaf culture after discovering their child was hearing impaired. This, compared to just 17.9% of minority parents in-general and only 9.1% of African American parents. Finally, there were no substantial differences noted for parents’ knowledge or experience gained about the different professionals providing hearing health services, nor any substantial differences in affirming their information about the use of sign language.

Parents’ responses varied little with respect to statements about their decisions to have their child fitted with a hearing aid or a cochlear implant. Virtually all parents with children fitted with a hearing aid or cochlear implant, regardless of non-minority or minority status, indicated they based their decision on information received from their hearing health care professional (e.g., ENT physician, Audiologist, etc.). A little over one-half (53.1%) of non-minority parents indicated they received additional information from other parents of deaf or hard of hearing children. This compared closely with the 41.8% of minority parents in general and 44.2% of African-American parents. Divergence was seen, though, with respect to information provided through promotional literature and government documents. Forty-four percent of non-minority parents affirmed that information provided by hearing aid and cochlear implant companies helped guide their decision to have their child either fitted with a hearing aid or a cochlear implant. Only 10.4% of minority parents in general, and no African American parents indicated agreement to using such materials in making their decisions. A similar pattern of divergence was also seen for information on hearing health care provided in government documents.

Acquisition and Use

As for factors relating to the acquisition and use of hearing health care services and related technologies (e.g., hearing aids, cochlear implants, assistive systems, etc.), two distinct areas of divergence emerged. Substantial percentages, 89.9% and 92.7% of minority parents in general and African American parents, respectively, agreed with the statement that hearing health care services and related technologies were too costly. This was in contrast to the 52.7 % of non-minority parents who agreed with the statement.

The most divergent response on this portion of the survey was to the statement about the availability of hearing health care services (e.g., audiology clinics, hearing aid outlets, etc.). Only one-half of 1% (.52%) of non-minority parents indicated that hearing health care services were not conveniently located in their communities. This is in stark contrast to the 86.5% and 90.7%, respectively, of minority parents in general and African American parents indicating that hearing health care services were not conveniently located. These two responses from African Americans, that hearing health care services and associated technologies are too costly and that services were unavailable in their communities had been identified previously by Jones & Richardson (1994) as the major reasons hearing impaired African-American senior citizens gave for their underutilizing hearing aids and hearing support services.

Finally, parents were asked to respond to the statement “The hearing health care services and related technologies with which I am familiar … Do not have service providers who are representative of my social/cultural background. Interestingly, none (0%) of the non-minority respondents affirmed this statement, whereas 94 % of minority parents in general and 96.6% of African-American parents agreed with it.

Parent Income

When the data were aggregated according to parent incomes, further disparities were noted between non-minority, minority in-general and African-American groups.. Calculating $40,000 as the median income for all respondents, 73.7% of non-minority parents had incomes within the upper category; as did 30% of minority parents in general, and 6.1% of the African American parents. When responses to the statements in Sections 2 and 3 of the survey were aggregated, the findings revealed, in general, that parents with moderate to high incomes (>$40,000), regardless of their racial or ethnic background, agreed to having knowledge of the nature of hearing rehabilitation services, and to acquiring such services for their children and using related hearing health care technologies to a greater extent than did parents with lower incomes (<$40,000). These findings suggest that socioeconomic status rather than race or ethnicity could be the more critical or discernable factor to account for the differences some parents reported in this study.

Limitations of Current Study

Although “oversampling” is an accepted and more recently popularized research method (Beech & Goodman, 2004), it can introduce broad levels of bias, which in turn, can limit the accuracy and possibly the validity of a study’s findings. In this investigation, where only one of the two cohorts were randomly selected (e.g., parent members of the ASDC), and the other targeted for inclusion because of their potential to yield a larger racial or ethnic minority response, the data are inextricably skewed. Immediately, variables such as income, educational background, occupation, etc. need to be considered. If this study were replicated, the use of a more random and stratified selection procedure, similar to that used by Craig et al (2002) would facilitate a more empirical approach and would likely yield more definitive results.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

Two specific outcomes in this study are worthy of noting, essentially because they align with the results of multiple other investigations (Hyde & Power, 2005; Jones, 1987; Bazargan et al, 2001; National Council on the Aging, 1999; Healthcare Research and Quality, 2004). These outcomes are: 1) racial and ethnic minorities use hearing health care services, hearing aids and cochlear implants at levels substantially below that of nonminorities, and 2) socioeconomics rather than race or ethnicity appears a more discernable factor to account for hearing health care disparities among minorities in general.

TABLE 6.

Combined “Strongly Agree” and “Agree” responses to survey questions about knowledge gained according to race and ethnicity classification

| Since discovering our child has a hearing loss we have learned something about… | Nonminorities | Minorities in general | African- Americans |

|---|---|---|---|

| …hearing therapy (aural rehabilitation) | 87.36* | 58.20 | 30.30 |

| …the causes of hearing loss | 53.15* | 23.88 | 21.21 |

| …the different professionals providing hearing health services | 80 | 89.55 | 90.90 |

| …the different methods of communicating with our child (i.e. total communication, cued speech, text messaging, etc.) | 86.84* | 26.86 | 21.21 |

| …educational and vocational opportunities for our child | 97.36* | 53.7 | 27.27 |

| …sign language (i.e., ASL). | 11.57 | 9.12 | 10.12 |

| …Deaf culture | 57.89* | 17.91 | 9.09 |

TABLE 7.

Combined percentages for “Strongly Agree” and “Agree” responses to survey questions about information sources according to race and ethnicity classification

| Our decision about having our child fitted with a hearing aid or being implanted with a cochlear implant was based on… | Nonminorities | Minorities in general | African- Americans |

|---|---|---|---|

| …information received from hearing health professionals (e.g., ENT doctors, audiologists, etc.) | 91.57 | 95.52 | 90.90 |

| …information received from other parents with deaf or hard of hearing children | 53.15 | 41.79 | 86.2* |

| …information provided in literature from hearing aid or cochlear implant companies | 43.68 | 19.40 | 0* |

| …information provided in government documents on hearing loss | 25.78 | 5.97 | 3.03 |

Acknowledgments

This investigator wishes to acknowledge the support of a number of persons who either consulted on the development of the survey questionnaire or assisted during data collection. These individuals include Mr. Ronald Lanier, Director, Department for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing, State of Virginia, Richmond, VA.; Dr. Claire Bernstein, Research Audiologist and Adjunct Professor in the Dept. of Hearing, Speech and Language Sciences at Gallaudet, Washington, D.C.; Mr. Curtis Humphries, former Marketing Director, Cochlear America, Denver, Co.; and, Ms. Kasha Mustin and Ms. Keena James, students from the Communication Sciences and Disorders program at Hampton University, Hampton, Virginia. This project was supported by research funds from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Research Infrastructure at Minority Institutions (RIMI) grant # 1P20MD001822-01, awarded through the Center for Biotechnology and Biomedical Sciences, Norfolk State University, Norfolk, Virginia.

APPENDIX A

July 2008

Dear Parent,

Please take a moment to read this letter. The information you are asked to provide in this survey will be used to help hearing health care providers determine why racial and ethnic minorities, who are Deaf or Hard of Hearing, do not use hearing health care services and hearing aid technologies to the same extent as their non-minority counterparts. As a parent of a child with a hearing impairment your thoughts and ideas on this issue are very important. The information gathered will help health care officials like me to discover better ways of providing hearing health care services and technologies to more people who need them.

You should understand that the information you provide will remain anonymous. Only the code number, which you select, will identify your survey responses. Your name will not appear in any reports, briefings, or in any future mailings you might receive regarding this survey. Know also that you have the right to withdraw your information from this study at any time.

I want to thank you in advance for your cooperation.

Sincerely,

Dr. Ronald Jones

Hearing Health Care Utilization Project Director

Center for Biotechnology and Biomedical Sciences

Norfolk State University

700 Park Avenue

Norfolk, VA 23504

Tel: 757 823-2365

Email: rjones@nsu.edu

APPENDIX B

“I understand that the information I provide in this survey will be anonymous and used to help determine why Deaf and Hard of Hearing individuals from ethnic minority backgrounds do not use hearing health care services and related technologies to the same extent as non-minority individuals.”

I agree to participate in the survey _______ (Check Here)

Please return this sheet and the completed survey in the pre-stamped, self-addressed envelope. Thank you.

I do not agree to participate in this survey ________ (check here). Please return the unanswered survey in the pre-stamped, self-addressed envelope. Thank you.

Signature ___________________________________________ Date___________

APPENDIX C

THE SURVEY

Instruction: Please select a 6 digit number to write in the space below.

_#______________

The number you select will be used to anonymously file your survey. You will want to keep a copy of this number available to refer to in any future contacts.

General Information –

| What is your racial or ethnic background: | Your child’s racial or ethnic background: |

| ____ White/Anglo American | ____ White/Anglo American |

| ____ Latino/Latina/Hispanic | ____ Latino/Latina/Hispanic |

| ____ Black/African American | ____ Black/African American |

| ____ Asian American | ____ Asian American |

| ____ Native American | ____ Native American |

| ____ Other: please state_____________ | ____ Other: please state____________ |

Your child’s gender:

_____Female

_____Male

Your child’s age? _____________

Where do you live?

City/State/Country ______________________________________

Family’s Income:

_____Less than $10,000 a year

_____Between $10,000 to $15,000 a year

_____Between $15,001 to $20,000 a year

_____Between $20,001 to $25,000 a year

_____Between $25,001 to $30,000 a year

_____Between $30,001 to $40,000 a year

_____Between $40,001 to $50,000 a year

_____Between $50,001 to $75,000 a year

_____Between $75,001 to $100,000 a year

_____Over $100,000 a year

_____Other_________________________________________________

How did you discover your child was hearing impaired? ________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Does your child have a cochlear implant?

____ No

____ Yes. How long has your child been implanted? __________________

Does your child where hearing aids?

____ No

____ Yes. How long has your child worn hearing aids?__________________

| What style of hearing aid ? | ___ Body |

| ___ Behind the ear | |

| ___ Eyeglass | |

| ___ In the ear |

Place an “X” in the space that best represents your response:

| Statements | Strongly Agree | Agree | Uncertain | Disagree | Strongly Disagree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Our decision about having our child fitted with a hearing aid or being implanted with a cochlear implant was based on… | |||||

| …Information received from professionals (e.g., audiologists, teachers, physicians, etc.) | |||||

| …Information received from other parents with Deaf or hard of hearing children | |||||

| …Information provided in literature from hearing aid or cochlear implant companies | |||||

| …Information provided in government documents on hearing loss | |||||

| …Other sources (__________) | |||||

| Our decision about having our child fitted with a hearing aid or being implanted with a cochlear implant was also based on… | |||||

| …Our concern about our child’s ability to effectively learn to use normal speech and oral language | |||||

| …Our decision not to have our child become a member of a Deaf community | |||||

| …Our not wanting to have to learn sign language | |||||

| …Other reasons (__________) |

Information and Knowledge

Place an “X” in the space that best represents your response:

| Statements | Strongly Agree | Agree | Uncertain | Disagree | Strongly Disagree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Since considering a hearing aid or cochlear implant for our child we have learned that… | |||||

| …hearing aids/cochlear implants work with everyone who wears one | |||||

| …Auditory rehabilitation following hearing fitting or implantation is almost as important | |||||

| …Our child can now hear perfectly | |||||

| …Our child wants to wear the hearing aid or implant all the time |

Racial and Cultural Perspectives

Place an “X” in the space that best represents your response:

| Statements | Strongly Agree | Agree | Uncertain | Disagree | Strongly Disagree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| My racial and/or ethnic background affects how I…. | |||||

| …Interact with other people, particularly, those who are racially or ethnically different from me | |||||

| …Interact with other people, particularly, those who are racially or ethnically similar to me | |||||

| …Causes me to see things around me differently | |||||

| …Makes me more sensitive to the cultural and ethnic differences in other people | |||||

| …Makes me more suspicious of others who are racially/ethnically different from me. | |||||

| Strongly Agree | Agree | Uncertain | Disagree | Strongly Disagree | |

| …Makes me less suspicious of others who are racially/ethnically different from me | |||||

| …Makes me more suspicious of others who are racially/ethnically the same as me. | |||||

| …Makes me less suspicious of others who are racially/ethnically the same as me. |

| Statements | Strongly Agree | Agree | Uncertain | Disagree | Strongly Disagree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Racial and ethnic minorities in this country do not participate in general health care as much as non-minorities because… | |||||

| …They are generally poorer and cannot afford the health care costs as can more non-minorities. | |||||

| …They are less informed than are non-minorities. | |||||

| …They do not live in areas where health care services are readily available. | |||||

| …They are less concerned about issues affecting their health than are non minorities. |

Thank you for your participation.

References

- Anderson GB, Bowers FG. Racism within the deaf community. American Annals of the Deaf. 1972;6:117–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beech BM, Goodman M. Race & Research: Perspectives on Minority Participation in Health Studies. American Public Health Association; Washington, D.C: 2004. p. 86. [Google Scholar]

- Craig A, Hancock K, Tran Y, Craig M, Peters K. Epidemiology of stuttering in the community across the entire lifespan. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research. 2002;45:1097–1105. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2002/088). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curns AT, Holman RC, Shay DK, Cheek JE, Kaufman SFMS, Rosalyn J, Singleton RJ, Anderson LJ. Outpatient and Hospital Visits Associated With Otitis Media Among American Indian and Alaska Native Children Younger Than 5 Years PEDIATRICS. 2002;109(3):e41. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.3.e41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison M, Dannhardt M, Roush J. Families’ Perceptions of Early Intervention Services for Children with Hearing Loss. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools. 1996 Jul;27:203–214. [Google Scholar]

- Hyde M, Power D. Some Ethical Dimensions of Cochlear Implantation for Deaf Children and Their Families Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education. 2005;11(1) doi: 10.1093/deafed/enj009. Retrieved (July, 2007) http://jdsde.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/full/11/1/102. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Institute of Medicine. Unequal treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. 2002 Retrieved October 20, 2008 from http://www.iom.edu/?id=16740. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Jones RC. Strategies for marketing hearing healthcare services to minority populations. Hearing Journal. 1987;40:1. [Google Scholar]

- Jones RC, Kretschmer LW. The Attitudes of Parents of Black Hearing-Impaired Students Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in the Schools. 1988 Jan;19:41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Jones RC, Richardson JT. A study of the availability of hearing healthcare services in African-American communities. ECHO. 1995;17:2. [Google Scholar]

- Kochkin S. Hearing Review 2005. 2005;12(7):16–2. [Google Scholar]

- Larson VD, Williams DW, Henderson WG, Luethke LE, Beck LB, Noffsinger D, et al. Efficacy of 3 commonly used hearing aid circuits: A crossover trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284:1806–1813. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.14.1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundeen C. Prevalence of Hearing Impairment Among School Children Lang Speech. Hear Serv Sch. 1991 Jan;22:269–271. [Google Scholar]

- Matusek P. Who are the disadvantaged and what should we do for them?. Paper presented at the American Education Research Association Convention; Toronto, Canada. 1977. [Google Scholar]

- National Healthcare Disparities Report: Summary. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, MD. : Feb, 2004. http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/nhdr03/nhdrsum03.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Proctor B, Dalaker J. Poverty in the United States: 2001. Current Population Reports. 2002 Retrieved September 20, 2008 from http://eric.ed.gov/ERICDocs/data/ericdocs2sql/content_storage_01/0000019b/80/1a/78/6b.pdf.

- Schildroth A, Rawlings B, Allen T. Hearing impaired children under age 6: A demographic analysis. American Annals of the Deaf, Reference Issue. 1989:63–69. doi: 10.1353/aad.2012.1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott D. Multicultural Aspects of Hearing Disorders and Audiology. In: Battle DE, editor. Communication Disorders in Multicultural Population. 3. Boston: Buttterworth-Heinemann; 2002. pp. 335–360. [Google Scholar]

- The National Council on the Aging. The Consequences of Untreated Hearing Loss in Older Persons. Washington, D.C.: 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The National Council on the Aging. The Consequences of Untreated Hearing Loss in Older Persons. Washington, D.C.: 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Health and Human Services. 2004 National Healthcare Disparities Report. Priority Populations: Racial and Ethnic Minorities. 2005;Chapter 4:87–100. AHRQ Publication No. 05 -0014. Available at: http://www.qualitytools.ahrq.gov/disparitiesreport/documents/nhdr2004.chap4.pdf.

- U.S. Census Bureau, Washington, D.S. 2007 Retrieved September 20, 2008 from http://www.infoplease.com/spot/hhmcensus1.html.

- US Department of Health and Human Services 2004 National Healthcare Disparities Report. Priority Populations: Racial and Ethnic Minorities. Chapter 4:87–100. AHRQ Publication No. 05 -0014. (March 2005). Available at: http://www.qualitytools.ahrq.gov/disparitiesreport/documents/nhdr2004.chap4.pdf.

- Van Naarden KP, Decoufle P, Caldwell KK. Prevalence and Characteristics of Children With Serious Hearing Impairment in Metropolitan Atlanta, 1991–1993. PEDIATRICS. 1999;103(3):570–575. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.3.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]