Abstract

One thousand one hundred and ninety six Palestinian adults living in the West Bank, Gaza Strip, and East Jerusalem were interviewed beginning in September 2007 and again at 6- and 12-month intervals. Using structural equation modeling, we focused on the effects of exposure to political violence, psychosocial and economic resource loss, and social support, on psychological distress, and the association of each of these variables on subjective health. Our proposed mediation model was partially supported. Exposure to political violence, psychosocial resource loss, and social support were related to subjective health, fully mediated by their relationship with psychological distress. Female sex and being older were also directly related to poorer subjective health and partially mediated via psychological distress. Greater economic resource loss, lower income, and poorer education were directly related to poor subjective health. An alternative model exploring subjective health as a mediator of psychological distress revealed that subjective health partially mediated the relationship between resource loss and psychological distress. The associate between female sex, education, income, and age on psychological distress were fully mediated by subjective health. Social support and exposure to political violence were directly related to psychological distress. These results were discussed in terms of the importance of resource loss on both mental and physical health in regions of chronic political violence and potential intervention strategies.

Keywords: PTSD, resource loss, trauma, political violence, occupation, war, health

Political-military occupation, conflict, and violence may have substantial public health implications, affecting both mental and physical health. In low income regions of the world, political violence may also result in a critical deterioration in economic conditions, educational and social services, availability of food and goods, and the availability of employment and income (Cardozo, Vergara, Agani, & Gotway, 2000; Johnson & Thompson, 2008; de Jong et al., 2001; Ai Al, Person & Ubelhor, 2002). The little research in this field has mainly focused on mental health outcomes of political violence, especially examining symptoms of post-traumatic stress (PTS) and depression. In general, war and ongoing political violence are associated with higher levels of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and symptoms of PTS (Bleich, Gelkopf, & Solomon, 2003; de Jong et al., 2001; Hall et al., in press; Hobfoll, Canetti-Nisim, & Johnson, 2006; Hobfoll et al., 2007; 2008; 2009; Johnson & Thompson, 2008; Shalev & Freedman, 2005). To a lesser extent, studies have shown that depression is also elevated during and after such events (Basoglu et al., 2005; Hall et al., 2008; Hobfoll et al., 2006; Miguel-Tobal et al., 2006; Tracy, Hobfoll, Canetti-Nisim, & Galea, 2008). Few studies, however, have examined the impact of war and political turmoil in low income countries or the predictors of symptoms of PTS and depression in such contexts (Basoglu et al., 2005; Cardozo et al., 2000; de Jong et al., 2001; Pham, Weinstein, & Longman, 2004; Vinck, Pham, Stover, & Weinstein, 2007). Moreover, there has been little attempt to examine how physical health is affected in these circumstances and how physical health might be related to psychological distress (Caspi, Saroff, Suleimani, & Klein, 2008).

Palestinians have experienced years of political-military occupation and military attack in the Israeli-Arab conflict. During the first and second Intifadas (uprisings) more than 6,200 Palestinians were killed (B'Tselem, 2008a, b), more than 60,000 wounded (JMCC, 2008; PCHR, 2008), and more than 65,000 have been detained (JMCC, 2008; B'Tselem, 2008a, c). Palestinians have also experienced a virtual civil war, as Palestinian factions fight for the leadership of Palestine with very different visions of what they hope to accomplish and how they hope the Palestinian State will be governed. These internal political tensions have led to gun battles, assassinations, and a division of the Palestinian Authority, with separate governing authorities in Gaza and the West Bank. Over 150 Palestinians are reportedly arrested by Palestinian Authority security forces in the West Bank each month and in Gaza over 250 people are being detained each month by the security forces of the de facto Hamas government. Over 590 individuals have been killed in internecine warfare between Palestinian political factions (B'Tselem, 2008a, b). The period prior to and during this study was a period of appreciable conflict, deaths due to political violence, as well as major economic distress.

The Association between Trauma, Psychological Distress, and Health

Trauma history is associated with both psychological distress and physical health problems (Dennis et al., 2009; Golding, 1994; Kimerling, & Calhoun, 1994). Among those who report trauma, both PTS and depression are related to health impairment when the trauma exposure is long-term and chronic (Zoellner, Goodwin, & Foa, 2000). It has also been noted that both depression and PTS mediate the impact of trauma exposure on physical health (Eadie, Runtz, & Spencer-Rodgers, 2008). For example, a study of Canadian bus drivers found that only those with trauma exposure and PTSD differed from non-exposed individuals on reports of more health treatment and poorer subjective health ratings (Vedantham, Brunet, Boyer, Weiss, Metzler, & Marmar, 2001). This appears to extend to a wide array of health problems, including subjective health, anemia, arthritis, asthma, back pain, diabetes, kidney and lung disease and ulcer (Weisberg et al., 2002).

The Role of Resource Loss in Contributing to Psychological Distress

One of the major factors linking trauma exposure to psychological distress is loss of material and psychosocial resources (Hobfoll, 1989; 1998). Conservation of Resources (COR) theory has been adopted to explain the impact of mass casualty trauma on individuals (Benight et al., 2000; Freedy, Shaw, Jarrell, & Masters, 1992; Hobfoll et al., 2006; Ironson, et al., 1997; Kaiser, Sattler, Bellack, & Dersin, 1996). Disaster, war, and terrorism are major traumatic events that share the important quality of being outside of people's control, occurring to large groups of people that share a social space (e.g., school, city, nation), and have the potential to cause great harm psychologically, socially, and physically (Hobfoll, 1989; 1998). Inherent in COR theory is the prediction that stress occurs primarily as a consequence of threat of resource loss or actual loss of resources that are highly valued by people (Hobfoll, 1989, 1998). Resources include both material resources (e.g., transportation, housing) and psychosocial resources (e.g., self-efficacy, social support). Several studies of disaster and mass casualty events have found that resource loss is a critical predictor of psychological distress following disaster (Freedy et al., 1992; Ironson et al., 1997). Likewise, studies of terrorism, war, and political violence have found that the loss of interpersonal, intrapersonal, and economic and material resources were key predictors of psychological distress (Galea et al., 2002; Hobfoll et al., 2009; Schlenger et al., 2002). Ironson et al. (1997) found that resource loss following disaster was the best single predictor of down regulation of victims' immune response.

Political violence and upheaval such that occurs in the Palestinian Authority threatens interpersonal resources such as social support. Nevertheless, those who sustain supportive social relationships in disaster and traumatic circumstances have been found to be more resilient (Benight et al., 2000; Galea et al., 2002; Norris & Kaniasty, 1996). Past research has found that perceived social support is especially important in the face of political violence, even in circumstances where personal resources appear to be outstripped (Bleich et al., 2003; Galea et al., 2002; Hobfoll et al., 2006; Palmieri, Galea, Canetti-Nisim, Johnson, & Hobfoll, 2008). Perhaps because people fear for both themselves and loved ones when they face war and political violence, studies of terrorism have found that contacting loved ones is one of the most common forms of coping following such circumstances (Bleich et al., 2003).

It is, of course, also possible that those who experience physical health problems will become more psychologically distressed. This path has not been previously considered in trauma research, but does fall within several trauma theories. First, one basic aspect of what is traumatic is that the person feels that they are unsafe (e.g., Punamaki, Komproe, Qouta, Elmasri, & de Jong, 2005). If people feel ill as a consequence of traumatic stressors, they are more likely to feel that their world has become unsafe as illness cues insecurity. Second, COR theory (Hobfoll, 1998) suggests that traumatic stress results, in part, from a rapid loss of resources, and here too, with illness, people may often feel that they are losing strength, capacity to cope, and vigor. Indeed, this pathway between poor physical health and psychological distress may be more rapid than the opposite pathway as psychological distress is a more immediate reaction to stressful circumstances, and physical health declines are typically seen as occurring following slower moving pathways such as immunological compromise and increased inflammatory processes (Dirkzwager, van der Velden, Grievink, & Yzermans, 2007).

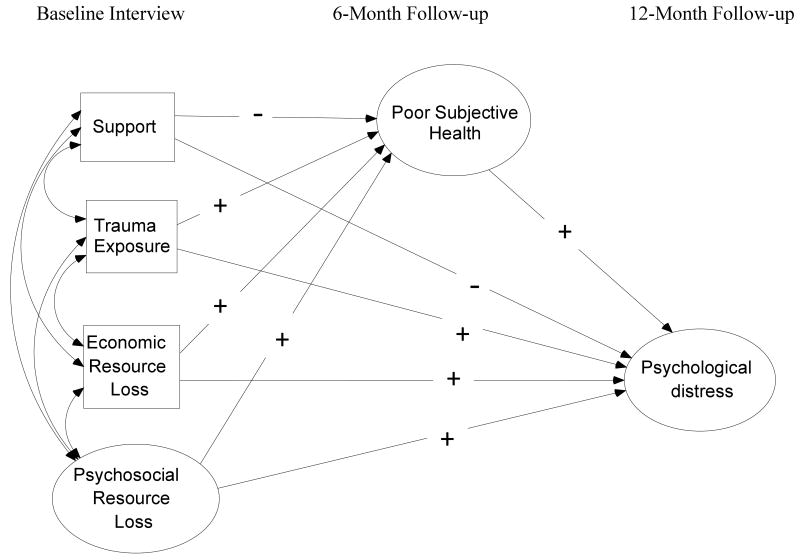

Based on this prior work, we proposed two possible models (see Figures 1 and 2). In the first model, it was predicted that trauma exposure and resource loss will together contribute to psychological distress as measured by PTS and depression symptoms. These symptoms, in turn, were predicted to mediate the impact of trauma exposure and resource loss on health outcomes. The model also suggested that to the extent people can nevertheless sustain social support, this should in part offset the impact of trauma exposure and resource loss on psychological distress, and through psychological distress on health outcomes. Finally, it was predicted that exposure to trauma and resource loss might have more minor direct impact on subjective health because stressors might impact subjective health directly and resource loss might make access to health care, medication, and rehabilitation more difficult to access.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized Structural Model for Subjective Health as a Mediator. Support = social support. Exposure = exposure to political violence. Psychosocial resource loss = intrapersonal and interpersonal resource loss. Psychological distress = posttraumatic stress symptom severity and depressive symptom severity. Poor subjective health = number of days that health has been poor in past 30 days and participant's overall health rating.

Figure 2.

Hypothesized Structural Model for Psychological Distress as a Mediator. Support = social support. Exposure = exposure to political violence. Psychosocial resource loss = intrapersonal and interpersonal resource loss. Psychological distress = posttraumatic stress symptom severity and depressive symptom severity. Poor subjective health = number of days that health has been poor in past 30 days and participant's overall health rating.

In the second, alternative model, we predicted that subjective health might mediate the impact of trauma exposure, resource loss, and social support on psychological distress. As people respond somatically due to stress they are likely to be more vulnerable to negative cognitions and feel weaker. This, in turn, could be translated to greater distress. That physical symptoms may precede or exacerbate PTSD and depression was illustrated in a recent study of battle-injured soldiers by Grieger and colleagues (2006). They noted that severity of physical problems was more strongly associated with later PTSD and depression than 1-month PTSD and depression.

We examined these models in a longitudinal three-wave panel study of a representative random sample of Palestinian citizens of the West Bank, East Jerusalem and Gaza. In addition to allowing an examination of these models, this study represents one of the only multi-wave studies of a region of such substantive conflict anywhere in the world.

Methods

We employed a stratified 3-stage cluster random sampling strategy for Palestinian adults living in the West Bank, Gaza Strip, and East Jerusalem. First, 60 clusters were selected with populations of 1,000 or more individuals (after stratification by district and type of community – urban, rural, and refugee camp) with probabilities proportional to size. Next, 20 households in each of the chosen clusters were selected. The third stage involved selecting one individual in each household using Kish Tables (these tables provide within-household randomization of participants). We visited each sampled household at least 3 times to complete the interview. After complete description of the study to the participants, written informed consent was obtained and they were paid the equivalent of about $5 (U.S.D.).

Three face-to-face interviews were conducted by same-sex interviewers. Interviewers were from the local area where they conducted interviews, were themselves Palestinian, and fluent in Arabic. They were trained in interview techniques, and most held college degrees or their equivalent. Baseline interviews were conducted from September 16th to October 16th, 2007, 6-month follow-up interviews from April 24, 2008 to May 17, 2008, and12-month follow-up interviews were conducted from October 15, 2008 to November 1, 2008. A structured interview comprising several self-report instruments was administered that has previously been translated and back-translated into Arabic for prior research and found to have sound psychometric properties in this population (Hobfoll et al., 2006; Hobfoll et al., 2008). The interview lasted approximately 45-minutes.

Of the 1,902 people approached for the first study wave, 702 refused to participate and 4 terminated the interview early, yielding a sample of 1196 people (a response rate of 63%). Of the original sample, an attempt was made to reach the 999 people who agreed to be contacted at 6-month follow-up. Of this sample, 110 were considered “non-contact” owing to change in address (18), refusal (52), unavailability for interview (36), being in prison (2), or being “martyred,” (2), yielding a response rate of 89%. For 12-month follow-up, 890 people were approached who agreed to be contacted again. Of this sample 98 were considered “non-contact” owing to change of address (15), refusal (32), unavailability (48), or sickness (3), yielding a final interview sample of 792, and a response rate of 89%. The rate of attrition in the overall study was 33.78%, which is excellent for a study of this size and the sociopolitical climate of the region. The institutional review boards of Kent State University, the University of Miami, Rush University and Medical College, and the University of Haifa approved this study.

Instruments

Demographic variables included: sex (coded 1 = male, 2 = female), education (less than high school, high school graduate, some college, college graduate), age, marital status (single, divorced/separated/widowed, married) and income. For income, participants were asked to report their income in relation to the average monthly household income in the Palestinian Authority (2,500 New Israeli Shekel; low: much lower than average or a little lower than average; medium: average; high: a little higher than average or much higher than average).

Exposure to political violence occurring in the past year was assessed by four open-ended items that were summed to indicate the total number of times the following occurred as a result of exposure to political violence: a death of a family member or a friend, an injury to a family member or a friend, an injury to themselves, or whether they had witnessed Israeli attacks or violence among Palestinian factions. An internal consistency reliability estimate was not calculated for this scale, as one exposure does not portend another.

Loss of interpersonal and intrapersonal resources related to exposure to political violence was assessed using a 9-item scale (5-items measured intrapersonal loss and 4-items measured interpersonal loss) from the Conservation of Resources Evaluation (COR-E; Hobfoll et al., 2006; Hall et al., 2008; Hobfoll & Lilly, 1993; Palmieri et al., 2008). Participants were asked “To what extent have you lost any of the following things in the past year as a result of the occupation or violence among factions?” Sample items for interpersonal loss include: “Feeling that you are a person of great value to other people,” “stability of your family,” and “intimacy with at least one friend.” Examples of intrapersonal losses are: “the feeling that you are a successful person,” “Sense of control in your life,” and “Hope.” Participants indicated the degree of their resource loss on a 4-point scale with item responses ranging from 1 (did not lose at all) to 4 (lost very much). Items were summed to create an interpersonal loss and intrapersonal loss score. Internal consistency reliability estimates was not calculated for these scales, as one loss does not portend another.

Economic resource loss was assessed by asking participants whether they suffered significant financial losses (e.g., to money or property) as a result of their exposure to political violence. Responses were coded 0 = no, 1 = yes.

Social support satisfaction was measured by two items of Weiss' (1974) social support provisions scale and were rated from 0 (not at all satisfied) to 3 (very satisfied). “How satisfied are you with the social support you receive from your…. “family” and “friends.” The items were summed to indicate overall support satisfaction. An internal reliability estimate for this scale was not calculated as one type of support may not relate to another.

PTS symptoms occurring within the past month that respondents associated with exposure to political violence were assessed with the 17-item PTSD Symptom Scale Interview format (PSS-I; Foa, Riggs, Dancu, Rothbaum, 1993). This scale has been used previously in non-Western, low income regions (Johnson & Thompson, 2008) and within the Israeli population (including both Palestinians and Jews) (Hobfoll et al., 2006; Hobfoll et al., 2008; Hall et al., 2008; Palmieri et al., 2008). Responses to items were given on a 4-point likert scale from 0 (not at all) to 3 (very much). The internal consistency reliability estimate was .87 at baseline interview, .86, at 6-month follow-up, and .89, at 12-month follow-up, in the current study.

Depression symptom severity was assessed using the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire, a well-validated, highly sensitive instrument for identifying symptoms of depression (Kroenke, Spitzer, Williams, 2001) consistent with the DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). It has been used previously in Israeli Palestinian populations (Hobfoll et al., 2008). Participants responded on a 4-point likert scale, 0 (not at all), 1 (several days), 2 (more than half the days), 3 (nearly every day). Sample items include “Little interest or pleasure in doing things,” “feeling down, depressed, or hopeless,” “feeling tired or having little energy.” The internal consistency reliability estimate was .88 at baseline interview, .89 at 6-month follow-up, and .90, at 12-month follow-up, in the current study.

Subjective health was assessed by two items derived from the Medical Outcomes Survey Short Form-36 (Ware & Sherbourne, 1992). The first item inquired about physical health-related functional impairment, “How many days in the past 30 days did your health prevent you from doing your usual activities?” For the next item, participants provided an overall rating of their health (“How would you rate your overall health during the past 30 days”), from 1 (very good) to 5 (poor).

Data Analyses

Estimated zero-order correlations were examined to assess the bivariate relationships among study variables. Two hypothesized mediation models were tested using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). Figure 1 displays our simplified hypothesized mediation model (i.e., demographic manifest indicators are omitted for ease of presentation). In order to evaluate the adequacy of this model to the observed data, a measurement model was first specified. Demographic variables (i.e., sex, age, income, education, marital status) that were potentially related to the outcomes were added to the model, and their pathways among all study variables were freely estimated. An initial partial structural model was then specified to evaluate the hypothesized relationships of exposure to political violence, psychological resource loss, economic resource loss, and social support (measured at baseline interview), predicting subjective health (measured at 12-month follow-up), and the hypothesized mediating role of psychological distress (measured at 6-month follow-up). The second alternative mediation model tested the hypothesized relationship of exposure to political violence, psychological resource loss, economic resource loss, and social support (measured at baseline interview), predicting psychological distress (measured at 12-month follow-up), and the hypothesized mediating role of subjective health (measured at 6-month follow-up). In order to increase model parsimony, non-significant correlations among variables in the measurement model were excluded from the initial models. We further trimmed non-significant structural model pathways after testing the initial models, and examined direct and indirect effects in final, respecified models. All paths in the models were tested and their direct and indirect effects on 12-month subjective health or 12-month psychological distress were simultaneously estimated (MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002; Shrout & Bolger, 2002).

Many methods for estimating the significance of indirect effects have been proposed in the literature. MacKinnon and colleagues (2002) compared the Type I error rates and power of 14 of these procedures. It was noted that the commonly used method described by Baron and Kenny (1986) actually yielded the lowest statistical power. Shrout and Bolger (2002) described a bootstrap procedure to estimate indirect effects that is superior to other options. Following the recommendations by Shrout and Bolger (2002) a bootstrap procedure was utilized in order to evaluate the significance of the study indirect effects (Shrout & Bolger, 2002). The 95% confidence intervals (CI) about the mean of the indirect effect are used to determine whether the effect is significant. If the CI does not include zero, the indirect effect is significant at the .05 level. The final, trimmed structural models were tested 1,000 times in order to produce 1,000 estimates for each path coefficient in the models, one for each of the 1,000 bootstrapped samples of the original data set (N=1197). The 1000 estimates were then combined in order to calculate the indirect effects. This procedure is automated in the AMOS program (Version 7; Arbuckle, 2006).

For all analyses missing data was imputed using the Estimation Maximization (EM) algorithm in the NORM software program (Schafer, 1999). This technique imputes missing data following an iterative maximum likelihood procedure, which utilizes all available participant data, making EM an efficient missing data handling technique (cf. listwise deletion). EM model based estimates of conditional means and the variance-covariance matrix take into account random error (Little & Rubin, 1987; Schafer, 1997). Simulation studies have demonstrated the clear advantage of using the EM algorithm versus pairwise or listwise deletion in cases where data is assumed to be missing completely at random, or the less stringent missing at random (Enders and Bandalos, 2001). Furthermore, EM is an excellent modern method for missing data handling given that it produces identical variance-covariance matrices as full information maximum likelihood estimation (Graham, 2003; Graham, Hofer, Donaldson, MacKinnon, & Schafer, 1997) and yields highly similar estimates as multiple imputation (Graham, 2003). The covariance coverage values, which reflect the proportion of data present to estimate each pairwise relationship, ranged from 66% to 100% in the current study. These values exceeded the recommended minimum of 10% for imputing missing data (Muthen & Muthen, 2002).

All measured continuous variables were examined for departure from normality. Exposure to political violence and the number of days of health-related impairment at each measurement wave had values indicating non-normal distributions. Following transformation, the univarite skewness and kurtosis values of the study variables indicated that all variables were normally distributed (West, Finch, & Curran, 1995). Model goodness of fit was assessed using the residual mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA), with values below.08 and a lower bound of the 90% confidence interval (CI) less than .05, indicating adequate fit (Browne & Cudeck, 1993) and the Comparative Fit Index (CFI; Bentler, 1990), with values greater than .95 indicating good fit. All data analyses were conducted using the AMOS program (Version 7; Arbuckle, 2006).

Results

The means, standard deviations, and percentages of study variables are presented in Table 1. The mean age of the sample was 35.03 years (SD =12.67). In terms of reported highest level of education, 34.3% finished elementary school, 32.0% finished high school, 10.9% completed some college, and 22.9% had a college degree. Annual household income was 51.7% below average 25.7% average, and 22.6% above average. In terms of marital status, 31.5% reported being single/divorced/separated/widowed and 68.5% reported being married. Our sample mirrored the known Palestinian Authority population demographics in age, economic status, region (the West Bank, Gaza and East Jerusalem), type of locality (cities, villages and refugee camps) and sex, (ICBS, 2007; PCBS, 1999, 2008) suggesting that we were successful in contacting a representative sample of the target population (Vinck et al., 2007).

Table 1.

Percentages, Means, and Standard Deviations for Study Variables

| Variable | % | M (SD) | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Female | 48.0 | ||

| Education | 2.22 (1.15) | 1 – 4 | |

| Age | 35.03 (12.67) | 18 – 80 | |

| Marital Status | |||

| Single | 31.5 | ||

| Married | 68.5 | ||

| Yearly Household Income | 1.70 (0.81) | 1 – 3 | |

| Exposure to Political Violence | 3.10 (6.29) | 1 – 62 | |

| Intrapersonal Resource Loss | 4.72 (3.75) | 0 – 15 | |

| Interpersonal Resource Loss | 2.85 (2.82) | 0 – 12 | |

| Economic Resource Loss | 0.33 (0.47) | 0 – 1 | |

| Social Support | 4.33 (1.58) | 0 – 6 | |

| T1 PTS Symptom Severity | 21.66 (9.40) | 0 – 51 | |

| T2 PTS Symptom Severity | 20.63 (8.96) | 0 – 49 | |

| T3 PTS Symptom Severity | 18.31 (9.62) | 0 – 47 | |

| T1 Depression Symptom Severity | 10.41 (6.06) | 0 – 27 | |

| T2 Depression Symptom Severity | 9.64 (6.28) | 0 – 27 | |

| T3 Depression Symptom Severity | 8.47 (6.24) | 0 – 27 | |

| T1 Number of days of health- related impairment | 2.16 (5.73) | 0 – 30 | |

| T2 Number of days of health- related impairment | 3.60 (6.43) | 0 – 30 | |

| T3 Number of days of health- related impairment | 3.12 (6.09) | 0 – 30 | |

| T1 Overall health rating | 2.11 (1.01) | 1 – 5 | |

| T2 Overall health rating | 2.15 (1.05) | 1 – 5 | |

| T3 Overall health rating | 2.03 (1.05) | 1 – 5 |

The estimated zero-order correlations among all study variables included in either SEM model are displayed in Table 2. For the mediation models, significant associations among exogenous variables and the outcome variables were included in the model as covariates.

Table 2.

Estimated Correlation Matrix of Latent Study Variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sex (female) | - | |||||||||||||

| 2. Education | -.07* | - | ||||||||||||

| 3. Age | -.02 | -.23*** | - | |||||||||||

| 4. Marital Status | .04 | -.17*** | .37*** | - | ||||||||||

| 5. Income | -.01 | .27*** | .03 | -.01 | - | |||||||||

| 6. Exposure | -.20*** | -.07* | -.01 | .01 | -.10*** | - | ||||||||

| 7. Resource loss | -.06 | -.13*** | .08* | .04 | -.08* | .14*** | - | |||||||

| 8. Economic Loss | -.06* | -.04 | .05 | .06* | -.05 | .24*** | .09** | - | ||||||

| 9. Social Support | .03 | .02 | -.03 | .04 | .01 | .02 | -.15*** | .02 | - | |||||

| 10. T1 Distress | .07* | -.11*** | .10** | -.00 | -.08** | .19*** | .63*** | .10** | -.09** | - | ||||

| 11. T2 Distress | .12*** | -.13*** | .11*** | .00 | -.06 | .14*** | .35*** | .06 | -.16*** | .56*** | - | |||

| 12. T3 Distress | .06 | -.14*** | .18*** | .08* | -.08** | .19*** | .37*** | .05 | -.14*** | .46*** | .67*** | - | ||

| 13. T1 Subjective health | .10** | -.25*** | .36*** | .11*** | -.12*** | .16*** | .29*** | .03 | -.11** | .39*** | .38*** | .40*** | - | |

| 14. T2 Subjective health | .11** | -.27*** | .42*** | .15*** | -.20*** | .03 | .18*** | .08* | -.06 | .29*** | .46*** | .47*** | .59*** | - |

| 15. T3 Subjective health | .12** | -.27*** | .41*** | .14*** | -.11*** | .06 | .14*** | .08* | -.09* | .22*** | .40*** | .64*** | .61*** | .77*** |

Note. Exposure = Exposure to Political Violence. Resource loss = Psychosocial resource loss. T1 = baseline interview. T2 = 6-month follow-up. T3 = 12-month follow-up.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

SEM Analyses

Mediation Model Evaluating the Role of Psychological Distress in Subjective Health

We first evaluated the hypothesized measurement model (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988). The model included eight manifest variables that were identified by their observed scores, and three latent variables that represented psychosocial resource loss, psychological distress, and subjective health. Psychosocial resource loss was specified by two manifest indicators measuring interpersonal and intrapersonal resource loss. Psychological distress was specified by the PTS symptom severity and depression symptom severity manifest indicators. Subjective health was specified by two observed health items: number of days with health-related impairment, and the participant's rating of their current health. All observed variables and latent variables were allowed to freely intercorrelate in the measurement model. The standardized loadings for the two psychosocial resource loss indicators were .88 and .84; .79 for PTS symptom severity and .86 for depression symptom severity on the latent psychological distress factor; and, overall health rating loaded .96 and days of health-related impairment loaded at .60 on the subjective health factor. These factor loadings and the fit indices for the measurement model indicated an adequate model fit to the underlying data structure, χ2(30, N = 1197) = 100.37, CFI = .978; RMSEA = .044, 90% CI = .035–.054.

Next, an initial structural model was specified to test the relationships of exposure to political violence, psychosocial and economic resource loss, social support and psychological distress on subjective health. Although allowed to freely correlate in the measurement model, non-significant associations among study predictors were omitted from the model to achieve a more parsimonious initial structural model. The initial model fit the data adequately well, χ2(54, N = 1197) = 161.66, CFI = .966; RMSEA = .041, 90% CI = .034–.048 (figure available on request). To assess the direct and indirect relationships between the study predictors and subjective health, non-significant model paths were trimmed. The final trimmed model accounted for the data quite well, χ2(58, N = 1197) = 165.88, CFI = .966; RMSEA = .039, 90% CI = .032–.047 (see Figure 3). Results of chi-square difference testing indicated that omitting these model paths did not lead to a significant decrement in overall model fit, χ2(4, N = 1197) = 4.22, p = .38). As would be expected, the structural relationships found in the initial model were replicated in the final, trimmed model. The following significant pathways were observed in predicting psychological distress: social support (β = -.10), exposure to political violence (β = .15), resource loss (β = .35), female sex (β = .17), and age (β = .10), explaining a total of 21% of the variance. In the prediction of subjective health, significant pathways were observed for economic resource loss (β = .06), education (β = -.12), female sex (β = .07), age (β = .31), income (β = -.07), and psychological distress (β = .29), explaining a total of 26% of the variance.

Figure 3.

Standardized structural equation modeling results of final trimmed model with subjective health as a mediator, demonstrating the relationship of social support, political violence exposure, economic and psychosocial resource loss, and psychological distress predicting subjective health. Support = social support. Exposure = exposure to political violence. Intra = intrapersonal resource loss. Inter = interpersonal resource loss. PTS = posttraumatic stress symptom severity. Depress = depressive symptom severity. Days = number of days that health has been poor in past 30 days. Rating = overall health rating. All coefficients at or above .10 are significant at p < .001, all others are p < .05.

The indirect effects of study variables were next examined to determine the extent to which psychological distress mediated the relationship between the study predictors and subjective health. Significant indirect and direct effects were observed for female sex and age, indicating that psychological distress partially mediated the relationship between each of these exogenous variables and overall health. Social support, exposure to political violence, and psychosocial resource loss did not have a direct effect on subjective health in the final model, and demonstrated an indirect relationship to this outcome. The effect of social support, exposure to political violence, and psychosocial resource loss on subjective health was fully mediated by psychological distress (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Bootstrap Analysis of the Magnitude and Statistical Significance of Indirect Effects for Mediation Model

| Independent Variable | Mediator Variable | Dependent variable | β standardized indirect effect | B mean indirect effecta | SE of meana | 95% CI mean indirect effecta (lower and upper) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Support→ | Psychological Distress→ | Subjective Health | (-.103) × (.286) = -.030 | -0.019 | 0.006 | -0.034, -0.009 |

| Resource loss→ | Psychological Distress→ | Subjective Health | (.345) × (.286) = .099 | 0.030 | 0.004 | 0.022, 0.039 |

| Exposure→ | Psychological Distress→ | Subjective Health | (.148) × (.286) = .042 | 0.120 | 0.029 | 0.066, 0.182 |

| Sex (female)→ | Psychological Distress→ | Subjective Health | (.170) × (.286) = .049 | 0.099 | 0.022 | 0.058, 0.144 |

| Age→ | Psychological Distress→ | Subjective Health | (.095) × (.286) = .027 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.001, 0.004 |

Note. Exposure = Exposure to Political Violence. CI = confidence interval.

These values are based on unstandardized path coefficients. Resource loss = psychosocial resource loss. All indirect effects are significant at p < .01.

Evaluating Subjective Health as a Mediator of Exposure, Resource Loss and Social Support and Psychological Distress

As above, we first evaluated the measurement model, which included eight manifest variables and three latent variables. Regarding the latent variables, the standardized loadings for the two psychosocial resource loss indicators were .89 and .83; .73 for PTS symptom severity and .85 for depression symptom severity on the latent psychological distress factor; and, overall health rating loaded .89 and days of health-related impairment loaded at .60 on the subjective health factor. These factor loadings and the fit indices for the measurement model indicated an adequate model fit to the underlying data structure, χ2(30, N = 1197) = 95.21, CFI = .979; RMSEA = .043, 90% CI = .33–.052.

Next, an initial structural model was specified to test the relationships of exposure to political violence, psychosocial and economic resource loss, social support and subjective health on psychological distress. As above, non-significant associations among study predictors were omitted from the model to achieve a more parsimonious initial structural model. The initial model fit the data well, χ2(52, N = 1197) = 126.21, CFI = .976; RMSEA = .035, 90% CI = .027–.042. To assess the direct and indirect relationships between the study predictors and psychological distress, non-significant model paths were trimmed. The final trimmed model accounted for the data quite well, χ2(59, N = 1197) = 131.98, CFI = .976; RMSEA = .032, 90% CI = .025–.040 (see Figure 3). Results of chi-square difference testing indicated that omitting these model paths did not lead to a significant decrement in overall model fit, χ2(4, N = 1197) = 5.77, p = .38). The following significant pathways were observed in predicting subjective health: female sex (β = .11), education (β = -.11), age (β = .38), income (β = -.16), and resource loss (β = .13), explaining a total of 26% of the variance. In the prediction of psychological distress, significant pathways were observed for resource loss (β = .30), social support (β = -.07), political violence (β = .08), and subjective health (β = .42), explaining a total of 34% of the variance.

We next examined the indirect effects of study variables to determine the extent to which subjective health mediated the relationship between the study predictors and psychological distress. Significant indirect and direct effects were observed for resource loss indicating that subjective health partially mediated the relationship between resource loss and psychological distress. Female sex, education, income, and age did not have direct effects on psychological distress in the final model, and demonstrated an indirect relationship to this outcome, and therefore their effects on psychological distress were fully mediated by subjective health (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Bootstrap Analysis of the Magnitude and Statistical Significance of Indirect Effects for Alternative Mediation Model

| Independent Variable | Mediator Variable | Dependent variable | β standardized indirect effect | B mean indirect effecta | SE of meana | 95% CI mean indirect effecta (lower and upper) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resource loss → | Subjective Health → | Psychological Distress | (.133) × (.415) = .055 | 0.114 | 0.743 | 0.055, 0.178 |

| Sex (female)→ | Subjective Health → | Psychological Distress | (.114) × (.415) = .047 | 0.656 | 0.656 | 0.290, 1.115 |

| Education→ | Subjective Health → | Psychological Distress | (-.107) × (.415) = -.044 | -0.268 | -0.268 | -0.446, -0.114 |

| Income→ | Subjective Health → | Psychological Distress | (-.161) × (.415) = -.067 | -0.570 | -0.570 | -0.812, -0.364 |

| Age→ | Subjective Health → | Psychological Distress | (.381) × (.415) = .158 | 0.087 | 0.087 | 0.067, 0.114 |

Note. Exposure = Exposure to Political Violence. CI = confidence interval.

These values are based on unstandardized path coefficients. Resource loss = psychosocial resource loss. All indirect effects are significant at p < .01.

Discussion

Our proposed model examining the role of psychological distress as a mediator was partially supported; the effect of economic loss on subjective health was not mediated by psychological distress. Trauma exposure, psychosocial resource loss, and social support were related to subjective health as mediated by their relationship with trauma-related psychological distress. The strongest path in this model was, as predicted, between psychosocial resource loss and subjective health, mediated by psychological distress. Only economic resource loss directly impacted subjective health ratings, with greater economic loss being related to poor subjective health. The alternative model, in which subjective physical health was modeled as a mediator of the impact of other predictors on psychological distress was only partially supported by the findings. Indeed, this model demonstrated that subjective health served only as a mediator of resource loss and psychological distress, but nevertheless suggested that subjective health is reasonably modeled as a mediator between the stressful aspects of community trauma, and the psychological distress people in such circumstances experience. This model further demonstrated that the direct association between subjective health and psychological distress was stronger than what was found the first model we tested, modeling psychological distress as a predictor of subjective health. Overall, these relationships predicted a sizable proportion of the variance in the outcome variables in each of the two tested models, which clearly indicates that the circumstances associated with occupation and the accompanying political violence have a major impact on health perceptions and psychological well-being, and that these two outcomes are transactional, affecting one another

These relationships are further clarified by the fact that they were independent of the influence of demographic factors. They also contribute to our knowledge of the impact of political violence and political occupation on physical health, as most studies have been descriptive or qualitative and lack theoretical bases (Hollified et al., 2002). Our results also coincide with those of Caspi et al., (2008), who found that among Bedouin veterans of the Israeli defense forces, that it was the combination of trauma exposure and psychological distress that was associated with physical health disorder. Caspi et al.'s (2008) study is especially informative as they included health impairments in daily functioning, physician-diagnosed medical conditions, and health visits. Similarly, O'Toole, and Catts (2008) found that it was through trauma's influence on psychological distress that veterans' health was found to be impaired. This latter work suggested that the chronic nature of psychological distress that follows trauma is consistent with altered inflammatory responsiveness that, in turn, results in a wide variety of health disorders.

Although subjective health ratings and psychological distress are not one in the same, it is not possible to fully disentangle how they are affecting each other. Even given our multi-wave data, the association between health status and psychological distress may well precede our initial assessment, setting a cycle in motion that cannot be exactly estimated. This said, our analyses suggest that as subjective health declines it results in increases in psychological distress, and that the inverse is also true, albeit to a lesser degree. Hence, our findings suggest that subjective health ratings actually had greater multi-wave influence on psychological distress, than did psychological distress on subjective health ratings. We must emphasize, however, that even with three waves we have studied a limited time frame and what we may have found in regard to psychological distress and physical health is that physical health rather quickly affects psychological distress, but that if psychological distress affects physical health we would expect that this would take more time to germinate and evolve.

Among demographic factors (see Table 3 and Table 4), it is notable that sex had both direct and indirect impact on subjective health and psychological distress. In this regard, women were found to report poorer subjective health and greater psychological distress both directly and through their greater psychological distress or poor subjective heath compared to men. Older individuals also reported poorer subjective health and greater psychological distress, and educated individuals reported better subjective health than less educated individuals. These findings are similar to those found following Katrina, where women, older individuals, and lower SES individuals both had greater sleep impairment, anxiety, and depression (Adeola, 2009). Likewise, following hurricane exposure, older individuals were both more likely to be depressed and to report poorer subjective health (Ruggiero et al., 2009), and among Lebanese citizens exposed to chronic war conditions, older and less educated individuals were more likely to report greater psychological distress (Roberto, Chaaya, Fares, & Khirs, 2006). These findings further support that those with fewer resources are more vulnerable to the negative impact of chronically stressful environmental conditions.

The question arises as to whether subjective health assessment is more about health or a reflection of psychological states influenced by trauma-related psychological distress. First, much research indicates that subjective and objective health reports are substantively related (McCullough & Laurenceau, 2004; Singh-Manoux et al., 2006). Further, subjective health assessment has been found to be important in its own right as it predicts both functioning and mortality, over and above the influence of objective health factors (Idler, & Benyamini, 1997; Wollinsky, & Johnson, 1992) Moreover, subjective health ratings are a good indicator of health behavior and how individuals will respond to their health circumstances in terms of exercise, smoking, adherence to medical care, and health care visits (Fylkesnes, 1993; Jakupcak, Luterek, Hunt, Conybeare, & McFall, 2008).

Perceived health may be particularly important for Palestinians as the chronic nature of the environmental stressors, overcrowding and poor health services have been emblematic of Palestinian refugee camps. There is nowhere else in the world where 60 years after being created that refugees are still in “temporary” camps. It is at this juncture that health meets politics, as the “temporary” refugee camps owe their longevity to the political process and Palestinian aspirations to return these refugees to Israel, with both sides blaming the other for the camp's continued existence. Indeed, this may link psychological distress to health perceptions, as the never-ending nature of the conflict undermines hope and may keep individuals from seeking to build their lives. This situation has been found to lead to what has been termed a “fragmented and incoherent” healthcare system, with as many as 10% of Palestinian children having stunted growth (Mataria et al., 2009). It is also likely that these health problems are related to the chronic nature of the stressors in this situation, as multiple trauma exposures over time is a major predictor of physical health problems (Sledjeski, Speisman, & Dierker, 2008).

Strengths and Limitations

This study had both limitations and strengths. A major limitation in making any causal interpretation of the data is that participants have long-term exposure to this conflict. Hence, the processes under study capture one period in time, but are interacting with a long prior history. Second, some respondents may have refused to participate out of political fears, and we cannot estimate how this might have affected our results. Also, at least some overlap between subjective health ratings and degree of psychological distress can be assumed, and to the extent that these constructs share variance, ratings of subjective health may be an artifact of distress rather than an accurate reflection of current healthfulness. Several of the measures of key constructs in the current study were necessarily short owing to the space limitations inherent in conducting a large scale longitudinal study such as this one. Given this limitation, this is still one of the few investigations into the role of trauma on subjective health and the relationship between health and trauma-related psychological distress. Strengths of the study include this being one of the only 3-wave studies of an area of such high level conflict ever studied with such large, random sampling on a national level. In particular, it is rare to have such careful interviews outside of Western contexts, although these have been increasing (Ai et al., 2002; Cardozo et al., 2000; Johnson & Thompson, 2008; Goenjian et al., 2000; de Jong et al., 2001). By random sampling, we also are able to analyze models include demographic variables that are themselves important.

Conclusions

This study provides critical insight into the process of chronic traumatic stress exposure of political violence and occupation which is unfortunately common in many regions of the world. It also provides valuable knowledge about how trauma exposure impacts mental and physical health and to the important resiliency value of social support. As prior studies have found major health problems for citizens of the Palestinian Authority (Mataria et al., 2009), our results yield information for potential intervention. Although we might not be able to reduce trauma exposure, intervention could aim at reducing secondary resource loss, supporting people's and communities' resource reservoirs, and buttressing social support. These processes have been referred to as the five principles of mass casualty intervention (Hobfoll et al., 2007), and include promoting: 1) sense of safety, 2) calming, 3) a sense of self-and-community efficacy, 4) connectedness, and 5) hope. Intervention in along these lines would both have the likely effect of reducing psychopathology and health problems.

Figure 4.

Standardized structural equation modeling results of final trimmed model with psychological distress as a mediator, demonstrating the relationship of social support, political violence exposure, economic and psychosocial resource loss, and subjective health predicting psychological distress. Support = social support. Exposure = exposure to political violence. Intra = intrapersonal resource loss. Inter = interpersonal resource loss. PTS = posttraumatic stress symptom severity. Depress = depressive symptom severity. Days = number of days that health has been poor in past 30 days. Rating = overall health rating. All coefficients at or above .10 are significant at p < .001, all others are p < .05.

Acknowledgments

This research was made possible in part by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (RO1MH073687).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/journals/tra

Contributor Information

Stevan E. Hobfoll, Rush Medical College

Brian J. Hall, Rush Medical College and Kent State University

Daphna Canetti, University of Haifa.

References

- Ai AL, Peterson C, Ubelhor D. War-related trauma and symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder among adult Kosovar refugees. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2002;15:157–160. doi: 10.1023/A:1014864225889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adeola FO. Mental health and psychosocial distress sequelae of Katrina: An empirical study of survivors. Human Ecology Review. 2009;16:195–210. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. text rev. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JC, Gerbing DW. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin. 1988;103:411–423. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. AMOS, Version 7. Spring House, PA: SPSS; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basoglu M, Livanou M, Crnobaric C, Franciskovic T, Suljic E, Duric D, et al. Psychiatric and cognitive effects of war in former Yugoslavia: Association of lack of redress for trauma and posttraumatic stress reactions. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 2005;294:580–590. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.5.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benight CC, Freyaldenhoven RW, Hughes J, Ruiz JM, Zoschke TA, Lovallo WR. Coping self-efficacy and psychological distress following the Oklahoma City bombing. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2000;30:1331–1344. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107:238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleich A, Gelkopf M, Solomon Z. Exposure to terrorism, stress-related mental health symptoms, and coping behaviors among a nationally representative sample in Israel. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;290:612–620. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.5.612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural equation models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- B'Tselem Fatalities in the first Intifada. 2008a Retrieved October 14, 2008, from http://www.btselem.org/english/statistics/First_Intifada_Tables.asp.

- B'Tselem Intifada fatalities. 2008b Retrieved October 14, 2008, from http://www.btselem.org/english/statistics/Casualties.asp.

- B'Tselem Statistics on Palestinians in the custody of the Israeli security forces. 2008c Retrieved October 14, 2008, from http://www.btselem.org/english/statistics/Detainees_and_Prisoners.asp.

- Cardozo BL, Vergara A, Agani F, Gotway CA. Mental health, social functioning, and attitudes of Kosovar Albanians following the war in Kosovo. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284:569–577. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.5.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi Y, Saroff O, Suleimani N, Klein E. Trauma exposure and posttraumatic reactions in a community sample of Bedouin members of the Israel Defense Forces. Depression and Anxiety. 2008;25:700–707. doi: 10.1002/da.20449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong JTVM, Komproe IH, Van Ommeren M, El Masri M, Araya M, Khaled N, et al. Lifetime events and posttraumatic stress disorder in 4 postconflict settings. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;286:555–562. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.5.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirkzwager AJ, van der Velden PG, Grievink L, Yzermans CJ. Disaster-related posttraumatic stress disorder and physical health. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2007;69:435–440. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318052e20a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis MF, Flood AM, Reynolds V, Araujo G, Clancy CP, Barefoot JC, et al. Evaluation of lifetime trauma exposure and physical health in women with posttraumatic stress disorder or major depressive disorder. Violence Against Women. 2009;15:618–627. doi: 10.1177/1077801209331410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eadie EM, Runtz MG, Spencer-Rodgers J. Posttraumatic stress symptoms as a mediator between sexual assault and adverse health outcomes in undergraduate women. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2008;21:540–547. doi: 10.1002/jts.20369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK, Bandalos DL. The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling. 2001;8:430–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Riggs DS, Dancu CV, Rothbaum BO. Reliability and validity of a brief instrument for assessing post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1993;6:459–473. [Google Scholar]

- Freedy JR, Shaw DL, Jarrell MP, Masters CR. Towards an understanding of the psychological impact of natural disasters: An application of the conservation resources stress model. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1992;5:441–454. [Google Scholar]

- Fylkesnes K. Determinants of health care utilisation. Visits and referral. Scandinavian Journal of Social Medicine. 1993;21:40–50. doi: 10.1177/140349489302100107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Ahern J, Resnick H, Kilpatrick D, Bucuvalas M, Gold J, et al. Psychological sequelae of the September 11 terrorist attacks in New York City. New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;346:982–987. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa013404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goenjian AK, Steinberg AM, Najarian LM, Fairbanks LA, Tashjian M, Pynoos RS. Prospective study of posttraumatic stress, anxiety, and depressive reactions after earthquake and political violence. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157:911–916. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.6.911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golding JM. Sexual assault history and physical health in randomly selected Los Angeles women. Health Psychology. 1994;13:130–138. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.13.2.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW. Adding missing-data relevant variables to FIML-based structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2003;10:80–100. [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW, Hofer SM, Donaldson SI, MacKinnon DP, Schafer JL. Analysis with missing data in prevention research. In: Bryant K, Windle M, West S, editors. The science of prevention: Methodological advances from alcohol and substance abuse research. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1997. pp. 325–366. [Google Scholar]

- Grieger TA, Cozza SJ, Ursano RJ, Hoge C, Martinez PE, Engel CC, Wain HJ. Postraumatic stress disorder and depression in battle-injured soldiers, American. Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:1777–1783. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.10.1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall BJ, Hobfoll SE, Canetti–Nisim D, Johnson R, Palmieri P, Galea S. Exploring the association between posttraumatic growth and PTSD: A national study of Jews and Arabs during the 2006 Israeli-Hezbollah War. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181d1411b. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall BJ, Hobfoll SE, Palmieri PA, Canetti-Nisim D, Shapira O, Johnson RJ, et al. The psychological impact of impending forced settler disengagement in Gaza: Trauma and posttraumatic growth. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2008;21:22–29. doi: 10.1002/jts.20301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll SE. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist. 1989;44:513–524. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.44.3.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll SE. Stress, culture, and community: The psychology and philosophy of stress. New York: Plenum Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll SE, Canetti-Nisim D, Johnson RJ. Exposure to terrorism, stress-related mental health symptoms, and defensive coping among Jews and Arabs in Israel. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:207–218. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.2.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll SE, Canetti-Nisim D, Johnson RJ, Palmieri PA, Varley JD, Galea S. The association of exposure, risk, and resiliency factors with PTSD among Jews and Arabs exposed to repeated acts of terrorism in Israel. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2008;21:9–21. doi: 10.1002/jts.20307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll SE, Lilly RS. Resource conservation as a strategy for community psychology. Journal of Community Psychology. 1993;21:128–148. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll SE, Palmieri PA, Johnson RJ, Canetti-Nisim D, Hall BJ, Galea S. Trajectories of resilience, resistance and distress during ongoing terrorism: The case of Jews and Arabs in Israel. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:138–148. doi: 10.1037/a0014360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll SE, Watson P, Bell CC, Bryant RA, Brymer MJ, Friedman MJ, et al. Five essential elements of immediate and mid-term mass trauma intervention: Empirical evidence. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes. 2007;70:283–315. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2007.70.4.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollifield M, Warner TD, Lian N, Krakow B, Jenkins JH, Kesler J, et al. Measuring trauma and health status in refugees: A critical review. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288:611–621. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.5.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idler E, Benyamini Y. Self-rated health and mortality: A review of twenty-seven community studies. Journal of Health and social behavior. 1997;38:21–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ICBS. Statistical abstract of Israel 2007 - no 58 subject 2 table no 7: Localities (1) and population, by district, sub-district, religion and population group. 2007. Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Ironson G, Wynings C, Schneiderman N, Baum A, Rodriguez M, Greenwood D, et al. Posttraumatic stress symptoms, intrusive thoughts, loss, and immune function after Hurricane Andrew. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1997;59:128–141. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199703000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakupcak M, Luterek J, Hunt S, Conybeare D, McFall M. Posttraumatic stress and its relationship to physical health functioning in a sample of Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans seeking post deployment VA health care. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2008 May;196:425–428. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31817108ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JMCC. Jerusalem Media and Communication Centre. The Intifada: An Overview: The First Two Years. 2008 Retrieved October 14, 2008, from http://www.jmcc.org/research/reports/intifada.htm#statist.

- Johnson H, Thompson A. The development and maintenance of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in civilian adult survivors of war trauma and torture: A review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:36–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser CF, Sattler DN, Bellack DR, Dersin J. A conservation of resources approach to a natural disaster: Sense of coherence and psychological distress. Journal of Social Behavior & Personality. 1996;11:459–476. [Google Scholar]

- Kimerling R, Calhoun KS. Somatic symptoms, social support, and treatment seeking among sexual assault victims. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62:333–340. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.2.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin N, Ensel WM. Life stress and health: Stressors and resources. American Sociological Review. 1989;54:382–399. [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. New York: Wiley; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mataria A, Khatib R, Donaldson C, Bossert T, Hunter D, Alsayed F, et al. The health-care system: an assessment and reform agenda. The Lancet. 2009;373:783–784. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60111-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough ME, Laurenceau JP. Gender and the natural history of self-rated health: A 59-year longitudinal study. Health Psychology. 2004;23:651–655. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.6.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miguel-Tobal JJ, Cano-Vindel A, Gonzalez-Ordi H, Iruarrizaga I, Rudenstine S, Vlahov D, et al. PTSD and depression after the Madrid March 11 train bombings. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2006;19:69–80. doi: 10.1002/jts.20091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus: The comprehensive modeling program for applied researchers [Computer program] Los Angeles: Muthen & Muthen; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Norris FH, Kaniasty K. Received and perceived social support in times of stress: A test of the social support deterioration deterrence model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;71:498–511. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.71.3.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Toole BI, Catts SV. Trauma, PTSD, and physical health: An epidemiological study of Australian Vietnam veterans. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2008;64:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmieri PA, Galea S, Canetti-Nisim D, Johnson RJ, Hobfoll SE. The psychological impact of the Israel-Hezbollah War on Jews and Arabs in Israel: The impact of risk and resilience factors. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;67:1208–1216. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PCBS. Population, housing, and establishment Census, 1997: Locality type booklet. Ramallah, Palestine: Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- PCBS. Palestine in figures, 2007. Ramallah, Palestine: Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- PCHR. Palestinian Center for Human Rights. Statistics related to Al Aqsa Intifada: 29 September, 2000- updated 27 August, 2008. 2008 Retrieved October 14, 2008, from http://www.pchrgaza.org/alaqsaintifada.html.

- Pham PN, Weinstein HM, Longman T. Trauma and PTSD symptoms in Rwanda: Implications for attitudes toward justice and reconciliation. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;292:602–612. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.5.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Punamaki R, Komproe I, Qouta S, Elmasri M, de Jong J. The Role of peritraumatic dissociation and gender in the association between trauma and mental health in a Palestinian community sample. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:545–551. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.3.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robero SB, Chaaya M, Fares JE, Khirs JA. Psychological distress after occupation: A community cross-sectional survey from Lebanon. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2006;11:695–702. doi: 10.1348/135910705X87536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggiero KJ, Amstadter AB, Acierno R, Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS, Tracy M, Galea S. Social and psychological resources associated with health status in a representative sample of adults affected by the 2004 Florida hurricanes. Psychiatry. 2009;72:195–210. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2009.72.2.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL. Analysis of incomplete multivariate data. New York: Chapman and Hall; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL. NORM: Multiple imputation of incomplete multivariate data under a normal model. University Park, PA: Department of Statistics, Pennsylvania State University; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Schlenger WE, Caddell JM, Ebert L, Jordan BK, Rourke KM, Wilson D, et al. Psychological reactions to terrorist attacks: Findings from the national study of Americans' reactions to September 11. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288:581–588. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.5.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalev AY, Freedman S. PTSD Following terrorist attacks: A prospective evaluation. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:1188–1191. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.6.1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:422–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh-Manoux A, Martikainen P, Ferrie J, Zins M, Marmot M, Goldberg M. What does self rated health measure? Results from the British Whitehall II and French Gazel cohort studies. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 2006;60:364–372. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.039883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sledjeski EM, Speisman B, Dierker LC. Does number of lifetime traumas explain the relationship between PTSD and chronic medical conditions? Answers from the National Comorbidity Survey-Replication (NCS-R) Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2008;31:341–349. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9158-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracy M, Hobfoll SE, Canetti-Nisim D, Galea S. Predictors of depressive symptoms among Israeli Jews and Arabs during the Al Aqsa Intifada: A population-based cohort study. Annals of Epidemiology. 2008;18:447–457. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vedantham K, Brunet A, Boyer R, Weiss DS, Metzler TJ, Marmar CR. Posttraumatic stress disorder, trauma exposure, and the current health of Canadian bus drivers. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry / La Revue canadienne de psychiatrie. 2001;46:149–155. doi: 10.1177/070674370104600206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinck P, Pham PN, Stover E, Weinstein HM. Exposure to war crimes and implications for peace building in Northern Uganda. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 2007;298:543–554. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.5.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware J, Sherbourne C. The MOS 36-item short form health-survey (SF-36): Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss RS. The provisions of social relationships. In: Rubin Z, editor. Doing unto others. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1974. pp. 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Weisberg RB, Bruce SE, Machan JT, Kessler RC, Culpepper L, Keller MB. Nonpsychiatric illness among primary care patients with trauma histories and posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatric Services. 2002;53:848–854. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.7.848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West SG, Finch JF, Curran PJ. Structural equation models with nonnormal variables: Problems and remedies. In: Hoyle RH, editor. Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1995. pp. 56–75. [Google Scholar]

- Wolinsky F, Johnson R. Perceived health status and mortality among older men and women. Journals of Gerontology. 1992 November;47:S304–s312. doi: 10.1093/geronj/47.6.s304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoellner LA, Goodwin ML, Foa EB. PTSD severity and health perceptions in female victims of sexual assault. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2000;13:635–649. doi: 10.1023/A:1007810200460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]