Abstract

Agonistic autoantibodies to the β-adrenergic and muscarinic receptors are a novel investigative and therapeutic target for certain orthostatic disorders. We have identified the presence of autoantibodies to β2-adrenergic and/or M3 muscarinic receptors by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay in 75% (15 of 20) of patients with significant orthostatic hypotension. Purified serum IgG from all 20 patients and 10 healthy control subjects were examined in a receptor-transfected cell-based cAMP assay for β2 receptor activation and β-arrestin assay for M3 receptor activation. There was a significant increase in IgG-induced activation of β2 and M3 receptors in the patient group compared to controls. A dose response was observed for both IgG activation of β2 and M3 receptors and inhibition of their activation with the non-selective β blocker propranolol and muscarinic blocker atropine. The antibody effects on β2 and/or M3 (via production of nitric oxide) receptor-mediated vasodilation were studied in a rat cremaster resistance arteriole assay. Infusion of IgG from patients with documented β2 and/or M3 receptor agonistic activity produced a dose-dependent vasodilation. Sequential addition of the β blocker propranolol and the nitric oxide synthase inhibitor NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester partially inhibited IgG-induced vasodilation (% of maximal dilatory response: from 57.7±10.4 to 35.3±4.6 and 24.3±5.8, respectively, p<0.01, n=3), indicating antibody activation of vascular β2 and/or M3 receptors may contribute to systemic vasodilation. These data support the concept that circulating agonistic autoantibodies serve as vasodilators and may cause or exacerbate orthostatic hypotension.

Keywords: orthostatic hypotension, vasodilation, agonistic autoantibodies, β-adrenergic receptor, muscarinic receptor, nitric oxide synthase

Introduction

Orthostatic hypotension (OH), generally defined as a drop in systolic/diastolic blood pressure (BP) of ≥20/10 mmHg within 3–10 min of standing, has a diverse pathophysiological basis. It is frequently associated with autonomic dysfunction caused by a variety of primary or secondary autonomic disorders.1–3 There are a high percentage of OH patients who have no known etiology and are assigned to the category of idiopathic OH. Several groups4–7 and we8–11 have demonstrated previously that agonistic autoantibodies to certain autonomic G-protein coupled receptors (GPCR) are associated with several cardiovascular diseases including hypertension, cardiomyopathy, myocarditis and cardiac arrhythmias, all of which have a variable degree of associated orthostasis. These autoantibodies are also found in the sera of healthy subjects, but generally in a lower frequency and in lower titers.12 They primarily target the second extracellular receptor loop and mediate physiologic effects.4, 13 We have recently reported for the first time the association of agonistic autoantibodies in 6 patients with demonstrable orthostasis.14 This mechanistic study demonstrated significant vasodilatory activity associated with autoantibodies directed toward the β2-adrenergic receptor (β2AR) and M3 muscarinic receptor (M3R). Although the IgG purified from these patients demonstrated marked vasodilatory activity, the combination of potentially opposing effects from other agonistic autoantibodies and their diverse presentation within the small number of patients made it difficult to develop an impression of the autoantibody frequency and physiological role in patients subject to orthostatic symptomatology.

The purpose of the present study is to expand our sample size, use new cell-based bioassays with transfected target receptors to examine the receptor-specific bioactivity of these autoantibodies and solidify our understanding of the mechanisms by which they may alter cardiovascular homeostasis. We also have the opportunity to initiate studies to examine the potential frequency of these agonistic autoantibodies in subjects who present with OH and the possible co-presence of autonomic neuropathy from a metabolic basis. Since OH is increasingly common in diabetics,15 we have included a group of OH patients with diabetes mellitus (predominantly Type 2) in the presence or absence of apparent associated autonomic dysfunction. This study demonstrates that autoantibodies targeting the β2AR and/or M3R are present in a majority of these OH patients and the autoantibodies possess sufficient bioactivity to alter the postural vascular response, thus contributing to the pathophysiology of OH.

Methods

Patients

Ten patients with idiopathic OH and 10 diabetic patients with OH, 5 with and 5 without concurrent gastroparesis were selected from 50 patients referred to the Oklahoma City VAMC, OUHSC Endocrinology Section and the Harold Hamm Diabetes Center for evaluation of OH symptoms. These 20 patients did not include the 6 idiopathic OH patients previously published,14 and were chosen based on the criteria for OH described below. Patients with evident hypotension from administration of antihypertensive drugs or apparent primary neurological diseases were excluded. Ten voluntary healthy control subjects were examined in order to obtain a “low estimate” of antibody presence and activity in a relatively younger population. This study was approved by the OUHSC IRB and the VAMC R&D Committee. All subjects provided written informed consent.

BP and heart rates were determined following a 5 min period of recumbency and after 5 and 10 min of upright posture. For this study, OH was defined as a drop in systolic BP of >20 mmHg or diastolic BP of >10 mmHg, and/or a lesser decrement in BP with an associated increase in heart rate of >15 bpm. All but 3 had a significant drop in systolic/diastolic BP of >20/10 mmHg. A diagnosis of OH with partial compensation was made in those 3 whose BP dropped by 12/8 mmHg but with an increase in pulse rate of >15 bpm demonstrating a partial cardiac compensatory response. Each recording was made in duplicate using a cuff matched for upper arm circumference. Indirect BP values were recorded by the PG3/4 fellows with experience using an automated Dinamap V100 instrument. The arm was generally supported in a slightly flexed position and the elevation relative to the heart kept constant during standing.

ELISA

The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was performed as described.8

Briefly, a 26-mer peptide (HWYRATHQEAINCYANETCCDFFTNQ)16 and 25-mer peptide (KRTVPPGECFIQFLSEPTITFGTAI)17 corresponding to the amino acid sequence of the second extracellular loop of human β2AR and M3R respectively were synthesized (GenScript, Piscataway, NJ) and used to coat ELISA plates at a concentration of 10 µg/mL in coating buffer. Sera were diluted 1:100, and goat anti-human IgG conjugated with alkaline phosphatase and its substrate para-nitrophenyl-phosphate 104 were used to detect antibody binding. The optical density (OD) values were read at 405 nm at 60 min.

IgG Preparation

IgG was purified from the patient or control sera using the NAb Protein A/G Spin Kit (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL).

cAMP Assay

IgG activation of β2AR was measured using the cAMP Hunter eXpress GPCR Assay kit (DiscoveRx, Fremont, CA), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, 30,000 cAMP Hunter eXpress β2AR-CHO cells were dispensed into each well of a 96-well culture plate and incubated overnight. The medium was then removed, and assay buffer containing the cAMP antibody and serum IgG (0.05–0.45 mg/mL) in the presence and absence of βAR blocker propranolol (1×10−8-1×10−6 mol/L) were sequentially added and incubated for 30 min. cAMP standard, negative (buffer) and positive (isoproterenol 100 nmol/L) controls were included in each assay. All samples were tested in triplicate. Following sample treatment, cAMP detection reagent and solution were added, and chemiluminescent signal was read on a TD-20/20 Luminometer (Turner BioSystems, Sunnyvale, CA). The cAMP values are expressed as percentage of buffer baseline to normalize the individual data.

β-arrestin Assay

IgG activation of M3R was measured using the PathHunter eXpress β-arrestin GPCR Assay kit (DiscoveRx, Fremont, CA), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The PathHunter β-arrestin technology monitors GPCR activity by detecting the interaction of β-arrestin with the activated GPCR using β-galactosidase enzyme fragment complementation. The β-arrestin recruitment occurs as a function of ligand activation of the target receptor. Briefly, 10,000 PathHunter eXpress β-arrestin M3R-CHO cells were dispensed into each well of a 96-well culture plate and incubated for 48 hrs. Assay buffer containing serum IgG (0.3–1.2 mg/mL) in the presence and absence of muscarinic blocker atropine (1×10−8-1×10−6 mol/L) were then added and incubated for 90 min. Negative (buffer) and positive (acetylcholine 100 nmol/L) controls were included in each assay. All samples were tested in triplicate. Following sample treatment, PathHunter detection reagents were added and chemiluminescent signal was read on the same luminometer. The β-arrestin recruitment levels are expressed as percentage of buffer baseline to normalize the individual data.

Isolated Arteriole Assay

The vasodilatory effect of patient IgG via activation of β2AR and M3R on resistance vessels was examined using an isolated rat cremaster arteriole assay as described.14, 18, 19 Briefly, cremaster resistance arterioles (70–80 µm) were surgically removed from anesthetized Sprague Dawley rats (180–250 g). A ~2 mm segment of the main intramuscular arteriole was microdissected, transferred to a 5.0 mL temperature-regulated superfusion chamber (Living Systems, St. Albans, VT) and cannulated at each end with glass micropipettes. Vessel segments were gradually pressurized to 70 mmHg and warmed to 34°C. The vessel preparation was positioned on the stage of an inverted microscope (Nikon TMS) equipped with a video-based imaging system (MyoCam, IonOptix, Milton, MA). Measurements of internal vessel diameter were made using a video edge detector (Model VED-205, Crescent Electronics, Sandy, UT). After equilibration and development of steady-state myogenic tone, the arterioles were perfused with serum IgG (10–300 µg/mL). The β blocker propranolol (1 µmol/L) was then added to the perfusate containing the maximal effective dose of IgG and the effect on vessel diameter was recorded for 5 min. At that point, the nitric oxide synthase inhibitor NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME, 100 µmol/L) was added to the IgG and propranolol and their cumulative effects were recorded until no further change in diameter was observed. The data are reported as percentage of maximal dilatory response to normalize the values. Maximal dilatory response was defined as the increase in diameter from basal tone to the maximal Ca2+-free passive dilation at 70 mmHg measured at the end of each preparation. This procedure was approved by the Oklahoma City VAMC and OUHSC IACUC.

Statistics

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Student’s t test and χ2 test were used for comparison of characteristics and hemodynamic parameters between patient and healthy control groups. Autoantibody positivity by ELISA was defined as OD values above the mean + 2SD from the control group. Control mean OD values were derived from log-transformed data because the distribution of OD is skewed. Autoantibody bioactivity values in the cAMP and β-arrestin bioassays were normalized to their respective baseline values. The positivity of bioactive autoantibodies was defined as bioactivity values above the mean + 2SD from the control group. Control mean bioactivity values were similarly derived from log-transformed data. Spearman rank correlation was performed to examine the relationships between ELISA and bioactivity values. Comparison between patient and healthy control groups was performed using the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. Differences in dose effects and vasodilation were assessed by a paired or unpaired Student's t test as appropriate. A Bonferroni correction was applied to adjust for multiple comparisons. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Compared to the healthy control group of 10 subjects with an assumed 10–15% positive rate for autoantibodies, positive rates as low as 60% for patient groups of 20, 70% for patient groups of 10, and 80% for patient groups of 5 could be detected as significantly different with 80% statistical power.

Results

Patient Characteristics

The OH patients were older than the healthy controls. These patients had a history of orthostatic symptoms and demonstrated a significant decrease in BP and/or a significant increase in pulse rate with only partial compensation of BP. Certain patients had a significant drop in BP and an inappropriate bradycardia demonstrating an inability to compensate for the drop in BP by an increase in cardiac output. The posture test results of all the subjects are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study subjects and their changes in blood pressure and heart rate during the 5-min standing test

| Characteristics & Parameters |

Healthy Controls (n=10) |

Idiopathic OH (n=10) |

Diabetic OH (n=10) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | 33.1±11.7 | 52.8±24.1 * | 60.8±10.5 ‡ |

| Sex (male:female) | 7:3 | 4:6 | 8:2 |

| Delta SBP | 0.4±7.0 | −32.2±21.8 ‡ | −29.3±19.4 ‡ |

| Delta DBP | 0.0±5.8 | −15.3±17.6 * | −11.1±6.5 ‡ |

| Delta HR | 5.2±4.3 | 12.2±11.6 | 7.2±7.3 |

Data are mean ± SD. OH, orthostatic hypotension; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HR, heart rate.

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001 compared to healthy controls by t test.

Autoantibody Screening by ELISA

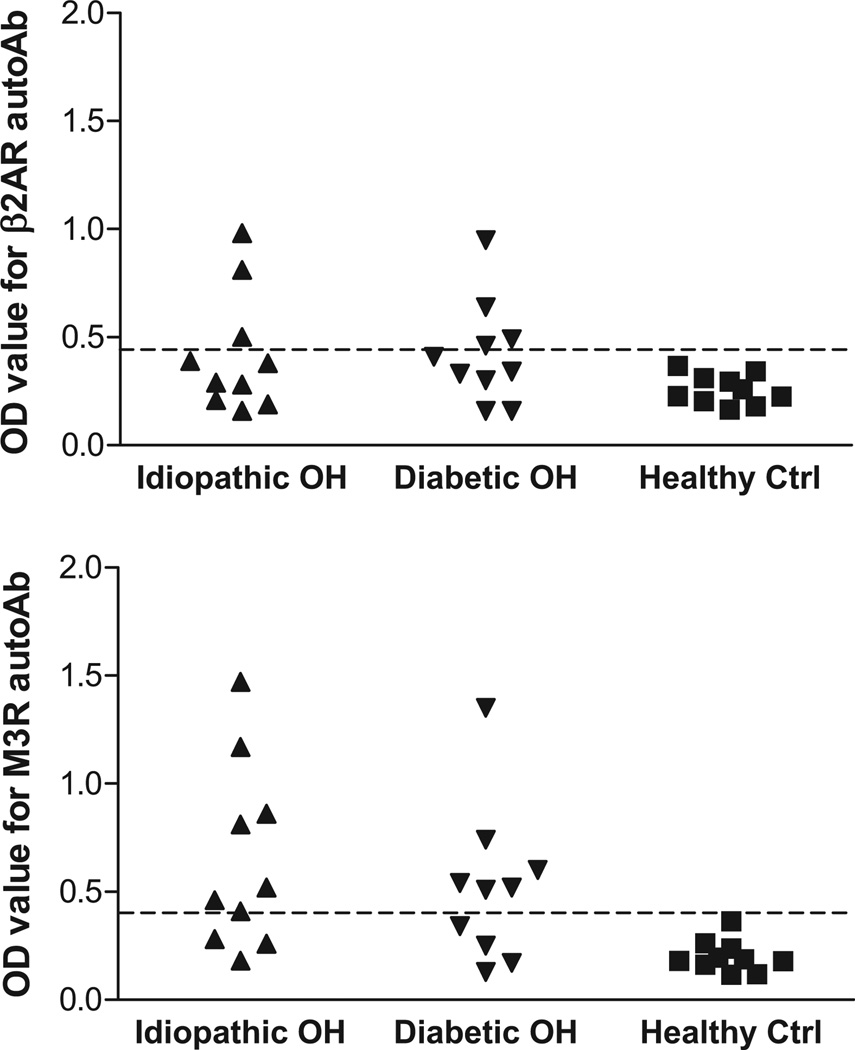

Sera were examined by ELISA for autoantibodies directed against β2AR and M3R. These data are shown in Figure 1. Among the 10 patients with idiopathic OH, 3 were positive for β2AR antibodies, 7 were positive for M3R antibodies, and 3 were positive for both antibodies. A similar percentage of antibody positivity was observed in the 10 diabetic OH patients (β2AR antibodies: 4; M3R antibodies: 6; β2AR and M3R antibodies: 2). In this small sample of diabetic patients with OH, the presence of gastroparesis, a marker of autonomic neuropathy, did not seem to influence results. Since the statistical power for this comparison was low, this observation requires replication in a larger study. Overall 75% (15 of 20) of the OH patients showed positivity for β2AR and/or M3R antibodies, and 25% (5 of 20) had coexisting antibodies.

Figure 1.

ELISA detection of autoantibodies (autoAb) to β2-adrenergic receptor (β2AR) and M3 muscarinic receptor (M3R) in orthostatic hypotension (OH) patients and healthy control (ctrl) subjects. Idiopathic OH, closed upward triangles; diabetic OH, closed downward triangles; healthy ctrl, closed squares; n=10 in each group. The dashed line is the threshold derived from the mean optical density (OD) values + 2SD of the healthy controls.

IgG Activation of β2AR and M3R in Cell-Based Assays

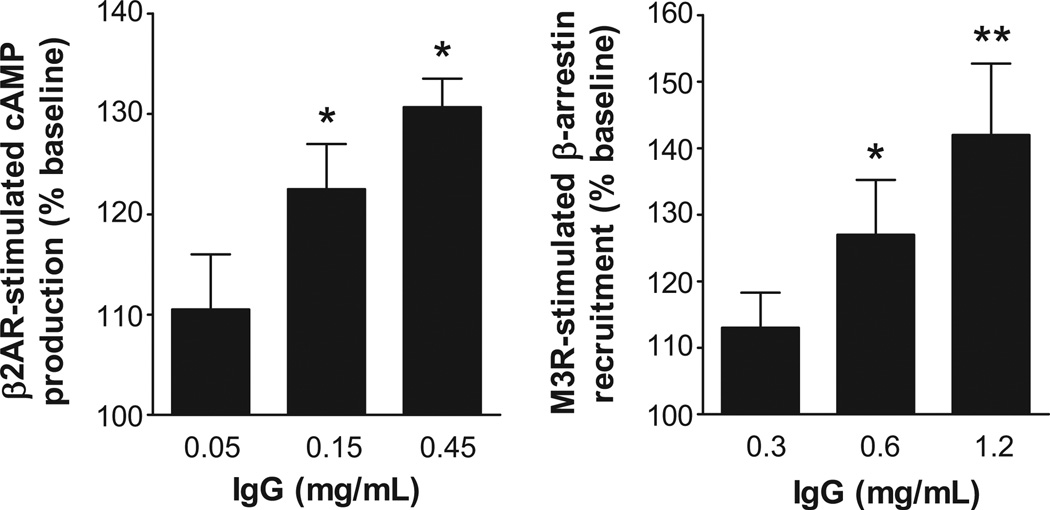

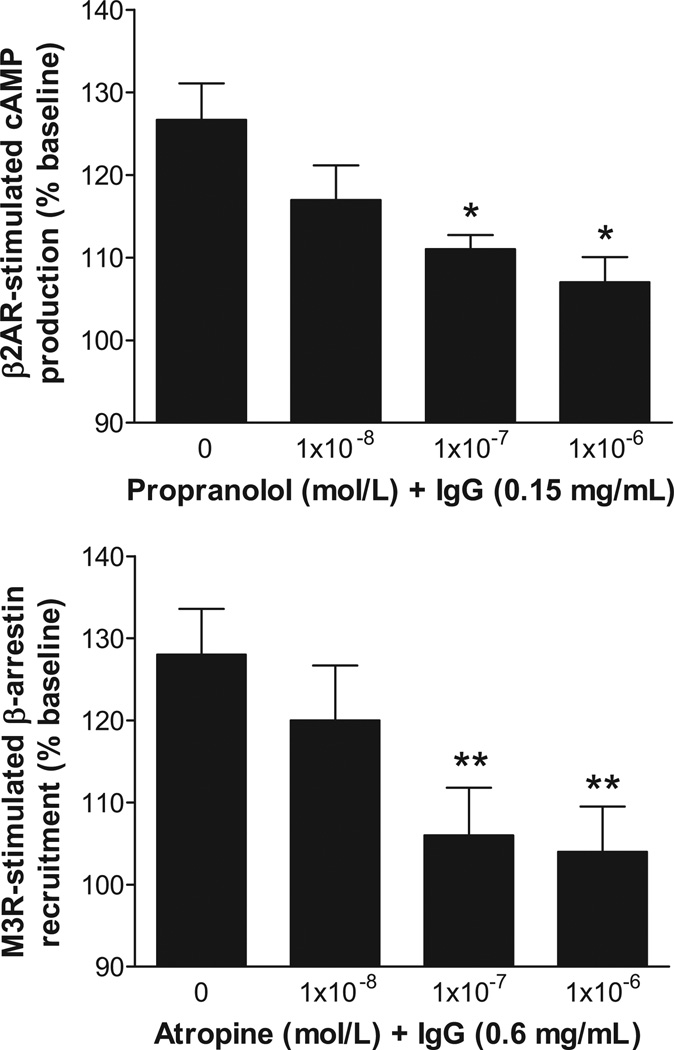

To examine the dose-responsive biological activity of the autoantibodies, IgG from 3 OH patients (2 idiopathic OH and 1 diabetic OH), who were strongly ELISA-positive for autoantibodies to β2AR and M3R were tested for their ability to activate β2AR and M3R in cultured cells using the cAMP Hunter and PathHunter β-arrestin technology. These assays provide an important parameter of cellular function relevant to the intrinsic activity of these autoantibodies. There was a significant dose effect on activation of both β2AR and M3R for these IgG samples (Figure 2). In addition, the IgG-induced activation of β2AR and M3R was effectively blocked in a dose-dependent fashion by the non-selective β blocker propranolol and muscarinic blocker atropine, respectively (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Dose effects of IgG from OH patients on β2AR activation of cAMP production and M3R activation of β-arrestin recruitment in specific receptor-transfected cultured cells. Values are expressed as % of baseline. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01 vs. baseline, n=3 (2 from idiopathic OH and 1 from diabetic OH).

Figure 3.

Dose effects of receptor blockade using propranolol and atropine respectively on IgG-induced activation of β2AR and M3R in specific receptor-transfected cultured cells. Values are expressed as % of baseline. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01 vs. IgG in the absence of receptor blockade, n=3 (2 from idiopathic OH and 1 from diabetic OH).

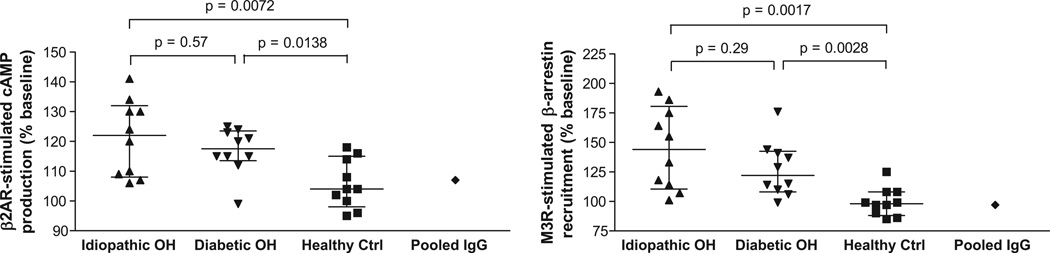

IgG from all 20 OH patients were then tested and demonstrated a variable but significant capacity to activate β2AR and M3R (Figure 4 and Table 2). The idiopathic OH and diabetic OH groups both showed significantly increased β2AR activation compared to healthy controls (p=0.007 and p=0.014 respectively). The increases in M3R activation in the idiopathic OH and diabetic OH groups were even more significant (p=0.002 and p=0.003 respectively) compared to healthy controls. There were no significant differences in autoantibody activity or frequency between the idiopathic OH group and diabetic OH group with or without concurrent gastroparesis, so the two subgroups with diabetic OH were combined for analysis with the caveat that the statistical power to detect all but extreme differences between these subgroups was low. An isoproterenol or acetylcholine stimulation, not shown, was performed with each assay as a positive control. Pooled normal human IgG (Sigma) also was tested and did not show any significant activation of β2AR and M3R (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Effects of IgG from OH patients and healthy control subjects on activation of β2AR and M3R in specific receptor-transfected cultured cells. Idiopathic OH, closed upward triangles; diabetic OH, closed downward triangles; healthy ctrl, closed squares; n=10 in each group. Pooled normal human IgG (closed diamond) also was included as a negative control. IgG was tested at a concentration of 0.15 mg/mL and 0.6 mg/mL for activation of β2AR and M3R, respectively. Values are expressed as % of baseline. Median values and interquartile ranges are shown. Group comparisons were performed by the Mann-Whitney test.

Table 2.

Comparison of IgG-induced activation of β2AR and M3R in cell-based bioassays between OH patients and healthy control subjects

| IgG source | β2AR activation | M3R activation |

|---|---|---|

| Median (Interquartile Range) | Median (Interquartile Range) | |

| Healthy Controls (n=10) | 104 (98–115) | 98 (89–108) |

| Idiopathic OH (n=10) | 122 (108–132) † | 144 (110–180) † |

| Diabetic OH (n=10) | 117 (113–123) * | 122 (108–142) † |

| All OH (n=20) | 120 (111–125) † | 131 (111–161) ‡ |

Data are expressed as % of baseline. β2AR, β2-adrenergic receptor; M3R, M3 muscarinic receptor; OH, orthostatic hypotension.

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001 compared to healthy controls by Mann-Whitney test.

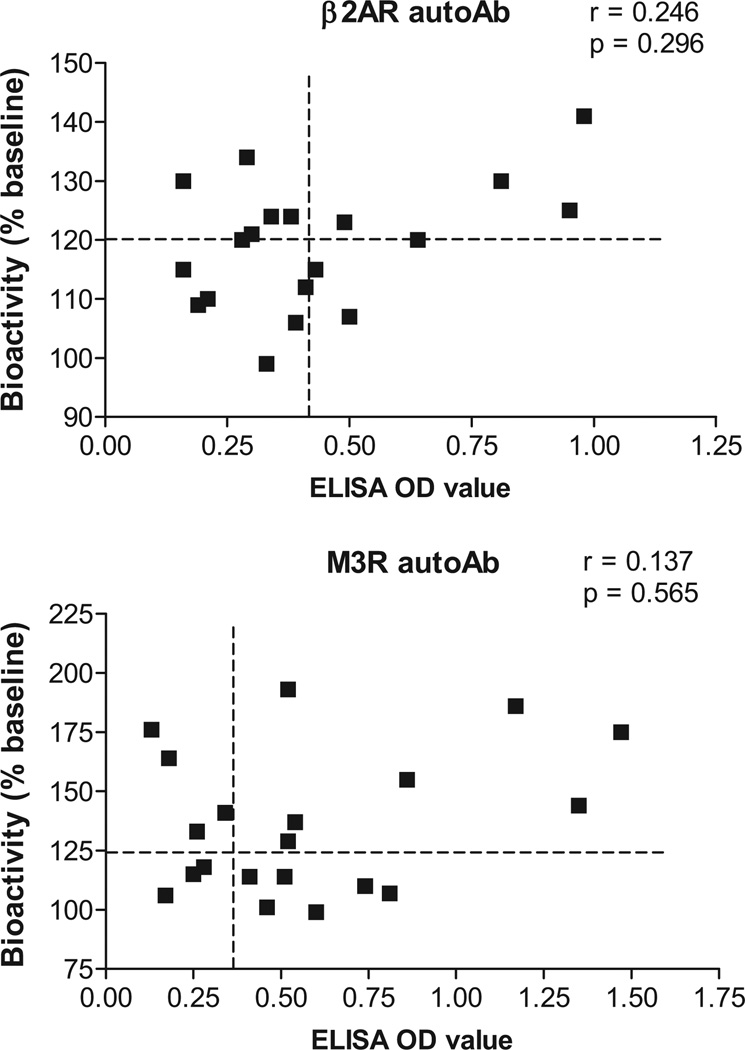

We have plotted the correlation of the individual OH subjects with their bioactivity measured by the receptor activation assays compared to their ELISA OD values in Figure 5. Although individuals with elevated ELISA values more frequently had significant bioactivity, others did not and the Spearman correlation coefficients failed to reach significance.

Figure 5.

Correlation analysis between ELISA and cell-based bioassays for autoantibodies to β2AR and M3R in the 20 OH patients. The vertical and horizontal dashed lines represent the cut-off values (mean + 2SD of healthy controls) for ELISA and bioassay positivity, respectively. No significant correlation was detected between ELISA OD values and bioactivity values.

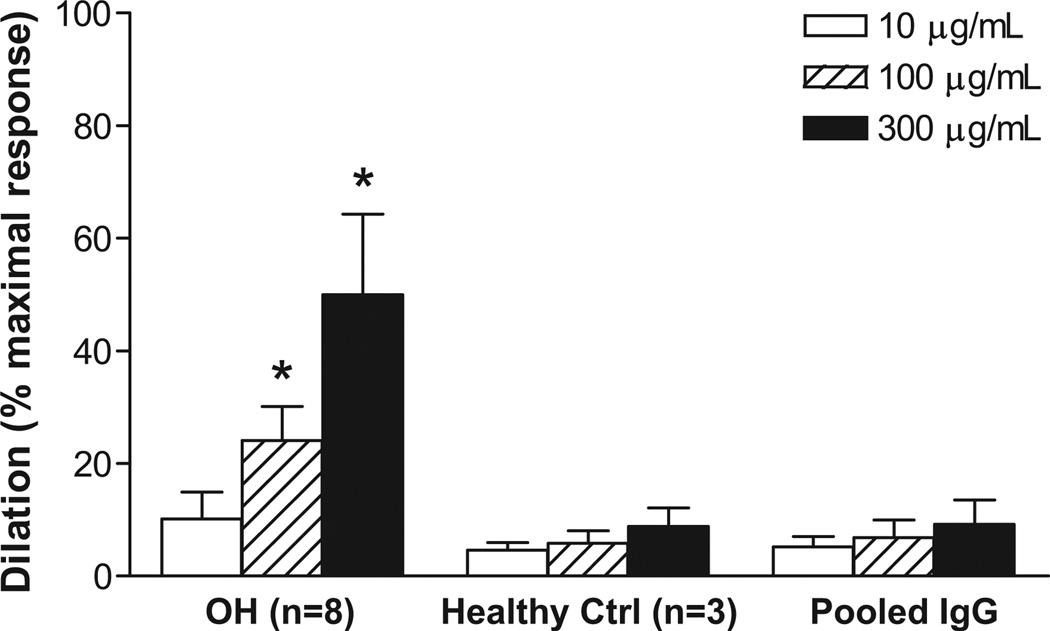

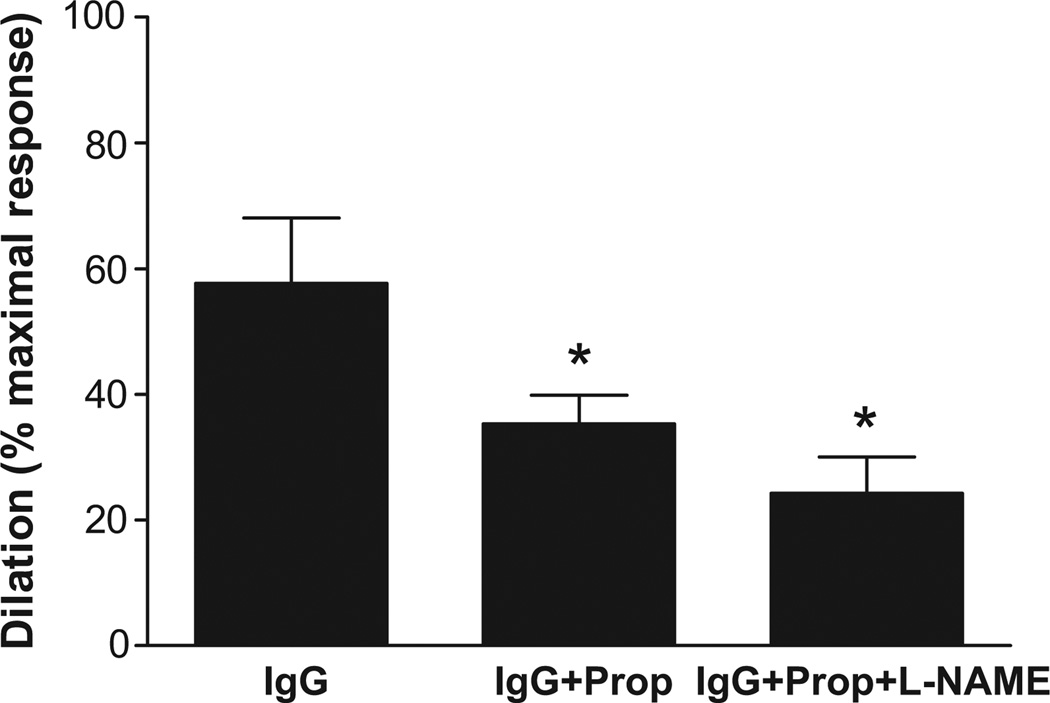

IgG-Induced Vasodilation

The vasodilator response to a 3-point dosage of IgG from 8 OH patients with documented β2 and/or M3 receptor agonistic activity from the cell bioassays was examined using a rat cremaster arteriolar assay (Figure 6). A significant dose effect on vasodilation was observed for all the tested IgG. Pooled, dialyzed normal human IgG (Sigma) and IgG from 3 healthy control subjects failed to produce any significant vasodilation. The effects of sequential addition of propranolol and L-NAME on vasodilation induced by IgG from 3 OH patients are shown in Figure 7. There was a significant decrease in IgG-induced vasodilation with non-selective β blockade and a further decrease with blockade of nitric oxide synthase by L-NAME (from 57.7±10.4% to 35.3±4.6% and 24.3±5.8%, respectively, p<0.01, n=3).

Figure 6.

Dose effects of IgG from 8 OH patients on basal spontaneous myogenic tone of rat cremaster arterioles. Values are expressed as % of maximal dilatory response, which is the increase in diameter from basal tone to the maximal Ca2+-free passive dilation at 70 mmHg measured at the end of each preparation. * p<0.01 vs. buffer control. Pooled normal human IgG and IgG from 3 healthy control subjects also were tested and did not show any significant vasodilatory effect.

Figure 7.

Effects of β-adrenergic blockade and nitric oxide synthase inhibition on IgG-induced arteriolar dilation. Values are expressed as % of maximal dilatory response. Sequential addition of the β blocker propranolol (Prop 10−6 mol/L) and nitric oxide synthase inhibitor NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME, 10−4 mol/L) following IgG infusion led to a progressive decrease in vasodilation (from 57.7±10.4% to 35.3±4.6% and 24.3±5.8%, respectively, p<0.01, n=3).

Discussion

OH is associated with increased mortality, causing falls and injury, impairing quality of life and complicating concurrent medication usage. Any pharmacological or endogenously produced autonomic vasodilation involving the systemic peripheral resistance will cause or accentuate orthostasis in susceptible subjects. While patients with obvious central or peripheral neuropathies have reason to demonstrate significant orthostasis, many other subjects have either minimal or no evidence for such a severe autonomic deficiency yet present with clinically relevant symptoms and signs of OH.

We previously hypothesized and subsequently demonstrated autoantibodies to β2AR and M3R are harbored in a subgroup of idiopathic OH patients and might contribute to the pathophysiology of OH.14 In that size-limited study, we provided mechanistic evidence that these receptor-activating autoantibodies intrinsically possess the capability of inducing significant systemic arteriolar vasodilation, and could be selectively antagonized by β blockade, inhibition of endothelial nitric oxide synthase and clinically by generalized muscarinic blockade.

We have used two commercially available specific receptor-transfected cell-based microassay kits to demonstrate that small amounts of IgG from such subjects are capable of activating β2AR and M3R. These kits provide the means for assay of larger numbers of subjects and will be useful for studies of intrinsic bioactivity since they respond appropriately to orthosteric agonists and antagonists. Using these assays, we have demonstrated that some patients with idiopathic and diabetic OH have significant activation of two different GPCR associated with peripheral vasodilation. The present study also uses a streamlined ELISA technique with the targeted receptor peptides relevant to GPCR activation. These assays demonstrate that detection of autoantibodies against one of the studied receptors may be common; however a small but significant number of patients have autoantibodies against both studied receptors. Although we had originally anticipated 30–40% positivity, we were pleasantly surprised to find the percentage as high as 70–75% in both the idiopathic and diabetic OH groups with more severe orthostasis. However, the ELISA technique has limitations. Firstly, the use of linear peptides as antigens carries the risk of missing conformational epitopes. Secondly, it is well established that ELISA alone will not detect all active antibodies,5, 13 and lastly, it will not predict functionality of the antibodies so detected. As expected, the correlation of antibody bioactivity with the ELISA data overall was not significant. We suspect some subjects have autoantibodies directed to the first rather than the second extracellular loop of their respective target receptor which may explain why some functionally positive subjects were ELISA negative to the second extracellular loop. Autoantibodies to the first extracellular loop of β1- and α1-adrenergic receptors have been reported to have receptor-activating capacity.7, 13

We have examined 8 of these subjects using an isolated resistance arteriole assay and demonstrated a pattern of IgG autoantibody-induced vasodilation very similar to that previously observed with the 6 OH patients from the previous publication. None of those patients were included in this present study and therefore adds to the documentation of a profound vasodilation associated with these autoantibodies. As before, we have confirmed with an additional 3 OH patients that β blockade without and with L-NAME blockade of endothelial nitric oxide synthase provide substantial but not complete return toward buffer baseline conditions. These data suggest that either the combined blockade was not complete, or another unidentified vasodilatory autoantibody(s) may be present. Other explanations include: these autoantibodies may have different affinity, may interact with each other and produce conformational changes which interfere with propranolol affinity and efficacy, or vice versa.20 Since a vasoconstrictive response was not observed following combined blockade, we did not find evidence for concurrent α1AR-activating autoantibodies.7 This remains to be confirmed since their presence might be counterbalanced by either incomplete vasodilatory blockade or the putative other vasodilatory autoantibody.

Orthostatic changes are not generally reported with use of orthosteric β2AR agonists such as in treatment of asthma. There are several reasons to believe this is not a parallel situation. Orthosteric ligands for virtually all GPCR quickly desensitize their target receptors resulting in limited function for the agonist’s intended use such as in asthma as well as for side effects. This desensitization is not observed for allosteric stimulatory autoantibodies in in vitro studies and therefore these autoantibodies have the potential for sustained activation.21 Secondly, vasodilation by β2AR autoantibodies will elicit a baroreceptor-mediated sympathetic response to compensate for the systemic effects. These changes at first may not be sufficient to exhaust the “compensatory homeostatic reserve” but in conjunction with other autoantibodies causing vasodilation (e.g. M3R activation) or limiting the cardiac rate (e.g. M2R activation), associated autonomic neuropathy (e.g. diabetes mellitus), or antibodies directed toward neural elements,22 patients may become symptomatic due to the presence of bioactive autoantibodies. We have observed some patients have coexisting autoantibodies and therefore complex interactions might be expected and vary from subject to subject.

Our finding that vasodilatory autoantibodies to β2AR and M3R are present in a high proportion of OH patients with and without apparent autonomic dysfunction suggests these autoantibodies may cause or exacerbate orthostasis by altering the compensatory postural vascular response.

Perspectives

We have confirmed and extended our observation that a subgroup of patients with OH demonstrates vasodilatory autoantibodies to β2AR and M3R which dilate resistance arterioles. Although isolated vasodilation is unlikely the sole cause of OH, these autoantibodies when present may be important co-culprits in the complex cardiovascular pathophysiology of OH. Our data reinforce the need for an expanded patient study with careful identification of subgroups, their pathophysiology and association with specific autoantibody activity. The inconsistent correlation between the peptide-based ELISA and functional assays indicates that both assays must be performed in parallel at the present time. Since orthosteric antagonists may not provide total protection against allosteric effects of these autoantibodies,13 specific removal of pathological autoantibodies or use of selective autoantibody antagonists will be a desirable goal and permit more definitive assessment of the importance of these autoantibodies.

These data must be interpreted with caution until confirmation by larger studies and by use of specific antagonists to counteract their activity in vivo. However, we believe this study should raise the hopes of patients and their physicians that newer approaches may improve the identification of previously unrecognized causes for OH and lead to new and improved pharmacological management of OH.

Acknowledgments

Source of Funding:

X.Y. has received support from NIH grant P20RR024215 from the COBRE Program of the National Center for Research Resources. This study was also supported in part by funding from NIH grant 5R01HL056267–12 (M.W.C., D.C.K.), Heart Rhythm Institute, OUHSC and a VA Merit Review grant (D.C.K., X.Y.) and individual grants from Will and Helen Webster and Britani T. and Paul E. Bowman, Jr.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: None.

References

- 1.Medow MS, Stewart JM, Sanyal S, Mumtaz A, Sica D, Frishman WH. Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment of orthostatic hypotension and vasovagal syncope. Cardiol Rev. 2008;16:4–20. doi: 10.1097/CRD.0b013e31815c8032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldstein DS, Sharabi Y. Neurogenic orthostatic hypotension: A pathophysiological approach. Circulation. 2009;119:139–146. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.805887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robertson D. The pathophysiology and diagnosis of orthostatic hypotension. Clin Auton Res. 2008;18 Suppl 1:2–7. doi: 10.1007/s10286-007-1004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wallukat G, Nissen E, Morwinski R, Muller J. Autoantibodies against the beta- and muscarinic receptors in cardiomyopathy. Herz. 2000;25:261–266. doi: 10.1007/s000590050017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caforio AL, Daliento L, Angelini A, Bottaro S, Vinci A, Dequal G, Tona F, Iliceto S, Thiene G, McKenna WJ. Autoimmune myocarditis and dilated cardiomyopathy: Focus on cardiac autoantibodies. Lupus. 2005;14:652–655. doi: 10.1191/0961203305lu2193oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lazzerini PE, Capecchi PL, Guideri F, Acampa M, Selvi E, Bisogno S, Galeazzi M, Laghi-Pasini F. Autoantibody-mediated cardiac arrhythmias: Mechanisms and clinical implications. Basic Res Cardiol. 2008;103:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s00395-007-0686-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wenzel K, Haase H, Wallukat G, Derer W, Bartel S, Homuth V, Herse F, Hubner N, Schulz H, Janczikowski M, Lindschau C, Schroeder C, Verlohren S, Morano I, Muller DN, Luft FC, Dietz R, Dechend R, Karczewski P. Potential relevance of alpha(1)-adrenergic receptor autoantibodies in refractory hypertension. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3742. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kem DC, Yu X, Patterson E, Huang S, Stavrakis S, Szabo B, Olansky L, McCauley J, Cunningham MW. Autoimmune hypertensive syndrome. Hypertension. 2007;50:829–834. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.096750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu X, Patterson E, Stavrakis S, Huang S, De Aos I, Hamlett S, Cunningham MW, Lazarra R, Kem DC. Development of cardiomyopathy and atrial tachyarrhythmias associated with activating autoantibodies to beta-adrenergic and muscarinic receptors. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2009;3:133–140. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stavrakis S, Yu X, Patterson E, Huang S, Hamlett SR, Chalmers L, Pappy R, Cunningham MW, Morshed SA, Davies TF, Lazzara R, Kem DC. Activating autoantibodies to the beta-1 adrenergic and m2 muscarinic receptors facilitate atrial fibrillation in patients with graves' hyperthyroidism. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1309–1316. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stavrakis S, Kem DC, Patterson E, Lozano P, Huang S, Szabo B, Cunningham MW, Lazzara R, Yu X. Opposing cardiac effects of autoantibody activation of beta-adrenergic and m2 muscarinic receptors in cardiac-related diseases. Int J Cardiol. 2011;148:331–336. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2009.11.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu HR, Zhao RR, Zhi JM, Wu BW, Fu ML. Screening of serum autoantibodies to cardiac beta1-adrenoceptors and m2-muscarinic acetylcholine receptors in 408 healthy subjects of varying ages. Autoimmunity. 1999;29:43–51. doi: 10.3109/08916939908995971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nikolaev VO, Boivin V, Stork S, Angermann CE, Ertl G, Lohse MJ, Jahns R. A novel fluorescence method for the rapid detection of functional beta1-adrenergic receptor autoantibodies in heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:423–431. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu X, Stavrakis S, Hill MA, Huang S, Reim S, Li H, Khan M, Hamlett S, Cunningham MW, Kem DC. Autoantibody activation of beta-adrenergic and muscarinic receptors contributes to an autoimmune orthostatic hypotension. J Am Soc Hypertens. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2011.10.003. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Low PA. Prevalence of orthostatic hypotension. Clin Auton Res. 2008;18 Suppl 1:8–13. doi: 10.1007/s10286-007-1001-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elies R, Ferrari I, Wallukat G, Lebesgue D, Chiale P, Elizari M, Rosenbaum M, Hoebeke J, Levin MJ. Structural and functional analysis of the b cell epitopes recognized by antireceptor autoantibodies in patients with chagas' disease. J Immunol. 1996;157:4203–4211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reina S, Sterin-Borda L, Orman B, Borda E. Human machr antibodies from sjogren syndrome sera increase cerebral nitric oxide synthase activity and nitric oxide synthase mrna level. Clin Immunol. 2004;113:193–202. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meininger GA, Zawieja DC, Falcone JC, Hill MA, Davey JP. Calcium measurement in isolated arterioles during myogenic and agonist stimulation. Am J Physiol. 1991;26:H950–H959. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1991.261.3.H950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hill MA, Zou H, Davis MJ, Potocnik SJ, Price S. Transient increases in diameter and [ca(2+)](i) are not obligatory for myogenic constriction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;278:H345–H352. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.2.H345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dror RO, Pan AC, Arlow DH, Borhani DW, Maragakis P, Shan Y, Xu H, Shaw DE. Pathway and mechanism of drug binding to g-protein-coupled receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:13118–13123. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104614108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Magnusson Y, Wallukat G, Waagstein F, Hjalmarson A, Hoebeke J. Autoimmunity in idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Characterization of antibodies against the beta 1-adrenoceptor with positive chronotropic effect. Circulation. 1994;89:2760–2767. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.6.2760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Etienne M, Weimer LH. Immune-mediated autonomic neuropathies. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2006;6:57–64. doi: 10.1007/s11910-996-0010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]