Abstract

Invisibility cloaks have recently become a topic of considerable interest thanks to the theoretical works of transformation optics and conformal mapping. The design of the cloak involves extreme values of material properties and spatially dependent parameter tensors, which are very difficult to implement. The realization of an isolated invisibility cloak in the visible light, which is an important step towards achieving a fully movable invisibility cloak, has remained elusive. Here, we report the design and experimental demonstration of an isolated polygonal cloak for visible light. The cloak is made of several elements, whose electromagnetic parameters are designed by a linear homogeneous transformation method. Theoretical analysis shows the proposed cloak can be rendered invisible to the rays incident from all the directions. Using natural anisotropic materials, a simplified hexagonal cloak which works for six incident directions is fabricated for experimental demonstration. The performance is validated in a broadband visible spectrum.

Invisibility cloak, a science fiction for ages, has now turned into a scientific reality thanks to the pioneering theoretical works in transformation optics1 and conformal mapping2. The invisibility cloak designed by the use of transformation optics doesn’t make the object disappear, but instead creates an illusion by guiding the light around the hidden object and making it appear on the other side without any deflection. The initial proposal for such a transformation-based cloak requires the materials to be inhomogeneous and anisotropic1,3. It involves extreme values of materials in the inner boundary and spatially dependent constitutive parameter tensors1. The first cylindrical cloak was experimentally achieved at microwave frequencies using metallic ring resonant metamaterials, which are strongly dispersive and work only in a narrow frequency band3. The bandwidth limitation for the cloak can be circumvented in some specific application situation, for example, in the applications targeted to hide an object sitting on a conducting ground plane. The cloak for this specific application was called carpet cloaks4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17, which are different from the cylindrical3,18,19 or spherical cloaks1 that can be classified as isolated object cloaks. They have limited cloaking potential, but have considerable advantage that, the parameters need not be singular4,20,21. The simple parameters lead to various experimental achievements from microwave frequencies to visible frequencies5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17. However, to achieve an isolated invisibility cloak is much more difficult because of the extreme values of the materials and the spatially dependent anisotropic parameters. Since the first experimental demonstration of the cylindrical cloak3 was reported in 2006, the operating frequency of isolated invisibility cloak has remained in the microwave frequencies22,23,24. The rare experimental works on isolated cloaks results from the fact that, to scale sub-wavelength resonant metamaterial elements and place them in a spatially dependent manner at optical frequencies is a highly challenging work. To realize an isolated cloak in the visible light, a key step towards achieving a fully movable cloak, we need to find a different way to remove the limitations associated with the initial proposal of the cloak. One solution to avoid the spatially dependent constitutive parameters in the cloak design is using linear homogenous coordinate transformation. The idea on homogeneous cloak was firstly studied in Ref [21], where a one-directional diamond cloak created with homogeneous material is proposed. The one-directional cloak21 is equivalent to a carpet cloak when the hidden object is sitting on a conducting ground plane. This point has been experimentally confirmed by several groups from microwave frequencies to visible frequencies5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17. The concept was later further extended to a two-step linear coordinate transformation, which was used to design different shaped cloaks25,26.

In this paper, we report a polygonal optical cloak that can hide an isolated macroscopic object in visible light. We propose a scheme to divide a polygon in a virtual coordinate space into lots of segments and apply a simple linear homogenous transformation in each segment. A big hidden region is transformed into a much smaller one, which can be hardly seen by the naked eye. The linear homogeneous transformation leads to homogenous and finite materials parameters in the cloak. Our theoretical work shows that the proposed cloak can be rendered invisible to the rays incident from all the directions. Using birefringent materials, a simplified hexagonal cloak which works for six incident directions is constructed to approximate the transformation based cloak. We successfully demonstrate that, in the whole visible spectrum, light can be guided through the cloak without it noticing the existence of the hidden object, and appearing on the other side without any deviation. Our work is a new step toward feasible human cloaking devises.

Results

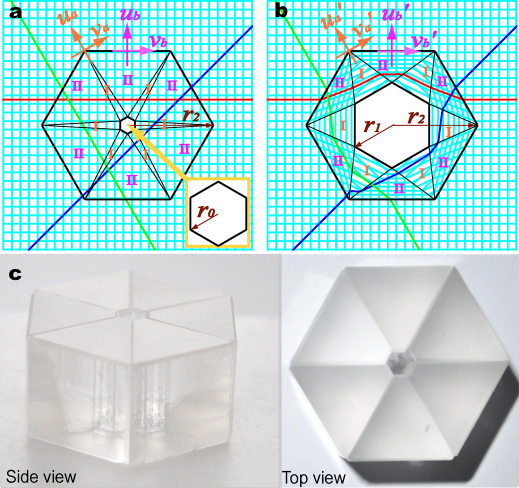

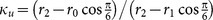

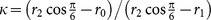

In the optical cloak design, an m-sided polygon is used in a virtual coordinate space (m = 6 in Fig. 1a), which is filled with isotropic material of permittivity  and permeability

and permeability  (

( = 1). In its center is a smaller polygon rotated at an angle of

= 1). In its center is a smaller polygon rotated at an angle of  compared to the outside polygon. The space between the two polygons is divided by several triangular segments. Due to the symmetric pattern shown in Fig. 1a, the triangular segments in the cloak can be grouped into two types, which we marked as Segment I and Segment II with their local coordinate axes, (

compared to the outside polygon. The space between the two polygons is divided by several triangular segments. Due to the symmetric pattern shown in Fig. 1a, the triangular segments in the cloak can be grouped into two types, which we marked as Segment I and Segment II with their local coordinate axes, ( ,

, ,

, ) and (

) and ( ,

, ,

, ), respectively. A linear homogeneous transformation method (see Methods Summary) is applied in all segments, along their local coordinate axes, so that the center polygon with radius

), respectively. A linear homogeneous transformation method (see Methods Summary) is applied in all segments, along their local coordinate axes, so that the center polygon with radius  in the virtual coordinate space is transformed to a bigger polygon with radius

in the virtual coordinate space is transformed to a bigger polygon with radius  in the physical coordinate space, while the outer polygon with radius

in the physical coordinate space, while the outer polygon with radius  in the virtual coordinate space remains the same as that in the physical coordinate space (Fig. 1b). If we only consider the trajectory of the light3,17,24, we can get the following nonmagnetic constitutive parameters for parallel polarized light (electric field is parallel to the polygon plane):

in the virtual coordinate space remains the same as that in the physical coordinate space (Fig. 1b). If we only consider the trajectory of the light3,17,24, we can get the following nonmagnetic constitutive parameters for parallel polarized light (electric field is parallel to the polygon plane):  ,

,  ,

,  , for Segment I, and

, for Segment I, and  ,

,  ,

,  , for Segment II, where

, for Segment II, where  ,

,  , and

, and  are the compression or extension ratios of the triangular segments (see Methods Summary). The cloak is formed by lots of such segments, whose materials are homogenous and anisotropic. No extreme values of the material parameters are involved. Different from the two-folded transformation scheme26, the linear transformation applied here is very simple, yielding simple constitutive parameters of the cloak. The hidden object, here the hexagon with radius

are the compression or extension ratios of the triangular segments (see Methods Summary). The cloak is formed by lots of such segments, whose materials are homogenous and anisotropic. No extreme values of the material parameters are involved. Different from the two-folded transformation scheme26, the linear transformation applied here is very simple, yielding simple constitutive parameters of the cloak. The hidden object, here the hexagon with radius  , is mapped to a hexagon with much smaller radius,

, is mapped to a hexagon with much smaller radius,  , and therefore, becomes much more difficult to be revealed to an outside observer. We can set

, and therefore, becomes much more difficult to be revealed to an outside observer. We can set  to be small enough so that it is invisible to the naked eye. In the virtual coordinate space, the trajectories of the rays marked as blue, red, and green are straight lines (Fig. 1a), while in the physical coordinate space, the rays are guided around the hidden object, and appear in the other region without any deflection (Fig. 1b). If we increase the number of sides of the polygon cloak (see Supplementary Information for a 20-sides polygon cloak), it would be very close to a cylindrical cloak but still, would be composed of homogeneous materials in each segment.

to be small enough so that it is invisible to the naked eye. In the virtual coordinate space, the trajectories of the rays marked as blue, red, and green are straight lines (Fig. 1a), while in the physical coordinate space, the rays are guided around the hidden object, and appear in the other region without any deflection (Fig. 1b). If we increase the number of sides of the polygon cloak (see Supplementary Information for a 20-sides polygon cloak), it would be very close to a cylindrical cloak but still, would be composed of homogeneous materials in each segment.

Figure 1. Illustration of the transformation optics based cloak design.

(a) The hexagon in the virtual coordinate space filled with isotropic materials is divided by lots of segments classified by Segment I and Segment II. (b) The hexagon cloak in the physical coordinate space is constructed by the transformed segments with anisotropic and homogenous optical properties. The hidden region defined by the center hexagon, with radius  in the physical coordinate space, is mapped from a much smaller hexagon, with a radius

in the physical coordinate space, is mapped from a much smaller hexagon, with a radius  in the virtual coordinate space. (c) The side and top views of a simplified hexagonal cloak, which consists of six calcite trapezoids glued together. The optic axis in each calcite trapezoid is parallel to its sides.

in the virtual coordinate space. (c) The side and top views of a simplified hexagonal cloak, which consists of six calcite trapezoids glued together. The optic axis in each calcite trapezoid is parallel to its sides.

In order to conceal a large object, the calculated electromagnetic parameters show that the materials in Segment I should have a big anisotropic degree ( ). Natural birefringent crystals are good candidates to construct the cloak for experimental demonstration10,11, but the anisotropic degree of most of these crystals (e.g. calcite is around 1.26) may be not big enough to squeeze a large space into a much smaller one. In order to observe a clear phenomenon of the cloaking effect in the experimental demonstration, we simplify the cloak design based on the trajectory and the refraction behavior of the horizontal ray marked in red in Fig. 1b. A simplified hexagonal cloak with only six segments is designed by replacing the Segment I materials in the original cloak with Segment II materials (see Supplementary Information for more details). This simplification sacrifices the performance of the cloak for other part of the rays, but can still approximate some properties of the original cloak. We can use natural birefringent crystal for experimental demonstration. The simplified hexagon cloak is fabricated by using six calcite trapezoids glued together (Fig. 1c). The calcite has a refractive index

). Natural birefringent crystals are good candidates to construct the cloak for experimental demonstration10,11, but the anisotropic degree of most of these crystals (e.g. calcite is around 1.26) may be not big enough to squeeze a large space into a much smaller one. In order to observe a clear phenomenon of the cloaking effect in the experimental demonstration, we simplify the cloak design based on the trajectory and the refraction behavior of the horizontal ray marked in red in Fig. 1b. A simplified hexagonal cloak with only six segments is designed by replacing the Segment I materials in the original cloak with Segment II materials (see Supplementary Information for more details). This simplification sacrifices the performance of the cloak for other part of the rays, but can still approximate some properties of the original cloak. We can use natural birefringent crystal for experimental demonstration. The simplified hexagon cloak is fabricated by using six calcite trapezoids glued together (Fig. 1c). The calcite has a refractive index  = 1.66 for ordinary light and

= 1.66 for ordinary light and  = 1.49 for extraordinary light. The optic axis in each calcite trapezoid is perpendicular to its sides, i.e. along the

= 1.49 for extraordinary light. The optic axis in each calcite trapezoid is perpendicular to its sides, i.e. along the  direction. The inner radius of the cloak is

direction. The inner radius of the cloak is  = 1.5 mm, and the outer radius of the cloak is

= 1.5 mm, and the outer radius of the cloak is  = 13 cm. The height of the cloak is

= 13 cm. The height of the cloak is  = 13 mm. The inner six surfaces of the cloak are coated with silver. Because of fabrication errors in the calcite crystal, the outer radius and the height of the cloak may have an error up to 1 mm, while the gap between two glued pieces of the cloak may have an error up to 0.3 mm.

= 13 mm. The inner six surfaces of the cloak are coated with silver. Because of fabrication errors in the calcite crystal, the outer radius and the height of the cloak may have an error up to 1 mm, while the gap between two glued pieces of the cloak may have an error up to 0.3 mm.

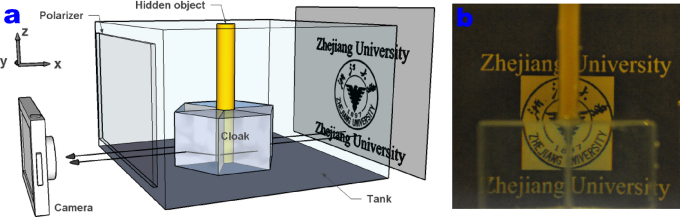

In the experimental setup (Fig. 2a), a yellow column with a radius of 1.3 mm is put inside the cloak as a hidden object. The upper part of the column is unwrapped by the cloak for comparison. The cloak with the hidden object is immersed in a glass tank filled with a transparent, light yellow, liquid with a refractive index of 1.72 at 589.3 nm. The letters and the logo of Zhejiang University, printed on a paper placed behind the tank in the yz plane, are used as an image. A polarizer is attached in front of the tank to ensure parallel wave polarization. A camera is also placed in front of the tank to capture the image. The image captured by the camera (Fig. 2b) is exactly what an observer sees through the tank and the cloak. As the upper part of the hidden column hasn’t been covered by the cloak, in the image captured by the camera, the letters ‘g’ and ‘U’ in the upper “Zhejiang University”, and the upper part of the logo are blocked by the column and cannot be fully seen. The lower part of the column is covered by the cloak, and we find that the lower part of the logo and all the letters in the lower “Zhejiang University” become visible. There is a small stripe in the center of the lower part of the image, which is introduced by the imperfect small gap in the gluing of the six calcite trapezoids. The logo and the letters in the captured image show no distortion and are located in the same position as the real objects, as if the hidden column were not there.

Figure 2. Experimental characterization of the optical cloak.

(a) Schematic of the experimental setup. (b) The image captured by the camera.

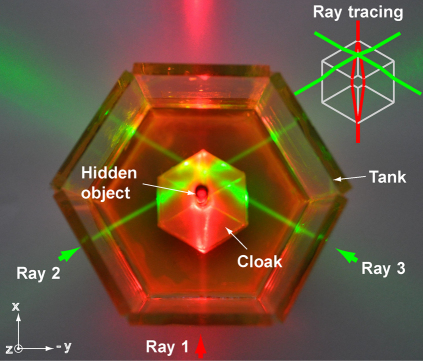

Due to the symmetric pattern of the cloak, the simplified cloak can also work for rays from the other five directions. In the second experiment, we use laser beams to demonstrate how the cloak manipulates the incident light to flow around the hidden object. Three lasers, two for green light (561 nm) and one for red light (650 nm), are used in the demonstration. The red beam from the laser is incident along the  direction, while the two green beams from the lasers are incident along the

direction, while the two green beams from the lasers are incident along the  and

and  directions, respectively (Fig. 3). In order to make sure the beams haven’t changed their directions when propagating from air into the liquids inside the tank, a hexagonal tank is fabricated and the cloak is put in the center of the tank. The laser beams are normally incident onto the three sides of the tank at different positions (Fig. 3). The original path of the red beam (Ray 1) is normally incident onto the hidden column. When it hits the cloak, the beam is split into two. The two split beams are smoothly guided around the hidden object, and emerge back as one beam at the other side of the cloak without any deviation. The cylindrical object at the center of the cloak is therefore invisible for this beam. The original paths of the two green beams (Ray 2 and Ray 3) are very close to the hidden object, although not normally headed to it. The cloak pushes the two beams further from the hidden object compared with the two split beams of Ray 1, and guides them back to their original path again. We see the cloak is able to manipulate the rays flow around the hidden object as if it were not there. A ray tracing model is also applied to demonstrate the path of the rays inside the cloak (the inset in Fig. 3), verifying the performance of the cloak.

directions, respectively (Fig. 3). In order to make sure the beams haven’t changed their directions when propagating from air into the liquids inside the tank, a hexagonal tank is fabricated and the cloak is put in the center of the tank. The laser beams are normally incident onto the three sides of the tank at different positions (Fig. 3). The original path of the red beam (Ray 1) is normally incident onto the hidden column. When it hits the cloak, the beam is split into two. The two split beams are smoothly guided around the hidden object, and emerge back as one beam at the other side of the cloak without any deviation. The cylindrical object at the center of the cloak is therefore invisible for this beam. The original paths of the two green beams (Ray 2 and Ray 3) are very close to the hidden object, although not normally headed to it. The cloak pushes the two beams further from the hidden object compared with the two split beams of Ray 1, and guides them back to their original path again. We see the cloak is able to manipulate the rays flow around the hidden object as if it were not there. A ray tracing model is also applied to demonstrate the path of the rays inside the cloak (the inset in Fig. 3), verifying the performance of the cloak.

Figure 3. The propagation of the laser beams through the cloak.

The three beams from different incident directions are manipulated by the cloak, flowing around the hidden object, and appearing at the other sides without any deviation. The inset (top right) shows the ray tracing of the three beams.

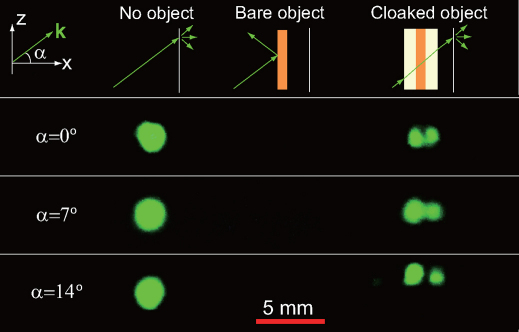

We next show the ability of the cloak in manipulating the beams that are obliquely incident onto the cloak. We change  , the angle between the wave vector of the incident wave and the horizontal

, the angle between the wave vector of the incident wave and the horizontal  plane while keeping the electric field to be horizontal by using a linear polarizer. Three cases are studied: no object, bare object, and cloaked object. The beam with green light propagates through these three cases before projecting onto a black screen (Fig. 4, first row). We use a camera to capture the image of the laser pattern on the screen. As the maximum

plane while keeping the electric field to be horizontal by using a linear polarizer. Three cases are studied: no object, bare object, and cloaked object. The beam with green light propagates through these three cases before projecting onto a black screen (Fig. 4, first row). We use a camera to capture the image of the laser pattern on the screen. As the maximum  that we can measure depends on the height of the cloak and the width of the laser beam, three different incident angles,

that we can measure depends on the height of the cloak and the width of the laser beam, three different incident angles,  ,

, , and

, and  , are selected for measurements. The images of the laser beam for the no object case are shown in the second column in Fig. 4, which are used as references. For the bare object case, the beam is totally blocked by the hidden object, resulting in a big shadow in the image (Fig. 4, third column). For the cloaked object case, the images of the beam in the screen are restored, indicating that the hidden object is well concealed by the cloak (Fig. 4, right column). Because the six pieces of the cloak cannot be glued perfectly during fabrication, there is a small gap in the center of the pattern. Compared with the big shadow in the bare object case, this gap is relatively small, without altering our conclusion on the cloaking effect. In previous literature, both the ray tracing model27 and the full wave electromagnetic scattering model28have shown that the transformation-based cylindrical cloak with ideal constitutive parameters has a three-dimensional behavior, i.e. it can hide an object from oblique incident waves, notwithstanding its transformation function being performed only in a two dimensional xy plane. In our experimental demonstration, the captured images of the transmitted beam at oblique incident angles clearly show the hidden object is well concealed, providing a complementary experimental evidence to support previous theoretical predictions27,28.

, are selected for measurements. The images of the laser beam for the no object case are shown in the second column in Fig. 4, which are used as references. For the bare object case, the beam is totally blocked by the hidden object, resulting in a big shadow in the image (Fig. 4, third column). For the cloaked object case, the images of the beam in the screen are restored, indicating that the hidden object is well concealed by the cloak (Fig. 4, right column). Because the six pieces of the cloak cannot be glued perfectly during fabrication, there is a small gap in the center of the pattern. Compared with the big shadow in the bare object case, this gap is relatively small, without altering our conclusion on the cloaking effect. In previous literature, both the ray tracing model27 and the full wave electromagnetic scattering model28have shown that the transformation-based cylindrical cloak with ideal constitutive parameters has a three-dimensional behavior, i.e. it can hide an object from oblique incident waves, notwithstanding its transformation function being performed only in a two dimensional xy plane. In our experimental demonstration, the captured images of the transmitted beam at oblique incident angles clearly show the hidden object is well concealed, providing a complementary experimental evidence to support previous theoretical predictions27,28.

Figure 4. Characterization of the cloak for oblique incidence.

The laser beam with parallel polarization is projected onto the screen after propagating through three cases: no object (second column), bare object (third column), and cloaked object (right column). The cloak successfully reconstructs the transmitted beam to remove the shadow of the hidden object.

Discussion

It should be noted that we use a simplified hexagonal cloak for experimental demonstration. Although the experimentally realized cloak (Fig. 1c) works for rays incident from only six incident directions, the theoretically proposed polygonal cloak (Fig. 1b) can work for rays incident from all directions. The lost performance is introduced by the simplification process of the experimental cloak where the Segment I materials with big anisotropic degree are removed (see Supplemental Information). This indicates that achieving highly anisotropic materials is very important to restore the omni-directional cloak performance in the future.

In conclusion, we report a new design and experimental demonstration of a polygonal cloak to hide an isolated object in visible light. The electromagnetic parameters of the cloak are finite and spatially independent. The cloaking performance is experimentally demonstrated by using a simplified hexagonal cloak. It works for the whole visible spectrum and does not require to be put on a reflective ground plane. The linear homogenous transformation method in the reported cloaking scheme can be very useful in future cloak design with different shapes and applications. It can be also extended into a new class of optical devices beyond invisibility cloak.

Methods

The hexagonal cloak (Fig. 1b) is designed through a linear homogenous transformation method. The transformation function from the original local coordinates in the virtual coordinate space (defined as [ ,

,  ] and [

] and [ ,

,  ] in Fig. 1a) into the new coordinates in the physical coordinate space (defined as [

] in Fig. 1a) into the new coordinates in the physical coordinate space (defined as [ ,

,  ] and [

] and [ ,

,  ] in Fig. 1b) is defined by:

] in Fig. 1b) is defined by:  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , where

, where  ,

,  , and

, and  are the compression or extension ratios of the space. Applying the coordinate transformation methods to Maxwell’s equations1, we get the following parallel polarized wave related constitutive parameters of the cloak:

are the compression or extension ratios of the space. Applying the coordinate transformation methods to Maxwell’s equations1, we get the following parallel polarized wave related constitutive parameters of the cloak:  ,

,  ,

,  , for Segment I, and

, for Segment I, and  ,

,  ,

,  , for Segment II. As far as the trajectory of light is concerned3,18, the constitutive parameters in the cloak can be simplified to the nonmagnetic reduced form as illustrated in the main text.

, for Segment II. As far as the trajectory of light is concerned3,18, the constitutive parameters in the cloak can be simplified to the nonmagnetic reduced form as illustrated in the main text.

The design of the simplified cloak with six segments is based on the trajectory of the horizontal propagating ray marked in red (Fig. 1b). In the original cloak, it travels through six boundaries and five triangles (two of Segment I medium and three of Segment II medium) before appearing at the other side of the cloak. The trajectory of the red ray is horizontal in the second Segment II medium so that the transmitted ray exhibits no deviation from the original one. We simplify the cloak by squeezing the triangles of Segment I medium to their symmetric lines so that Segment I medium disappears. At the same time, we enlarge the space of Segment II medium. The simplified cloak is therefore composed of only Segment II medium. To make the simplified cloak still work for the red ray, i.e. for the ray trajectory to be horizontal in the second Segment II medium, we can inversely get the electromagnetic parameters of the background material by using Snell’s refraction law at the boundaries. In the Supplemental Information, a k-surface diagram is used to show the derivations of the parameters of the simplified cloak and the background medium.

Author Contributions

Author contribution statement Both authors contribute equally to this work. H.C. proposed the idea, supervised the experiments, interpreted the results, and wrote the manuscript. B.Z. carried out the experiments and interpreted the results.

Supplementary Material

Broadband polygonal invisibility cloak for visible light__Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. James Chen, Dr. Nauman Javed, Dr. Yang Xu for helpful discussions. Financial supports from NSFC grants 60801005, 60990320 and 60990322, the FANEDD grant 200950, the ZJNSF grant R1080320, the MEC grant 200803351025, and the FRFCU grant 2011QNA5020 are gratefully acknowledged.

References

- Pendry J. B., Schurig D. & Smith D. R. Controlling electromagnetic fields. Science 312, 1780-1782 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonhardt U. Optical conformal mapping. Science 312 , 1777-1780 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schurig D. et al. Metamaterial electromagnetic cloak at microwave frequencies. Science 314, 977-980 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J. & Pendry J. B. Hiding under the carpet: a new strategy for cloaking. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 203901 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R. et al. Broadband ground-plane cloak. Science 323, 366-369 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentine J., Li J., Zentgraf T., Bartal G. & Zhang X. An optical cloak made of dielectrics. Nat. Mater. 8, 568-571 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabrielli L. H., Cardenas J., Poitras C. B. & Lipson M. Silicon nanostructure cloak operating at optical frequencies. Nat. Photon. 3, 461-463 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Ma H. F. & Cui T. J. Three-dimensional broadband ground-plane cloak made of metamaterials. Nat. Commun. 1, 21 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ergin T., Stenger N., Brenner P., Pendry J. B. & Wegener M. Three dimensional invisibility cloak at optical wavelengths. Science 328 , 337-339 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B., Luo Y., Liu X. & Barbastathis G. Macroscopic invisibility cloak for visible light. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 033901 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Luo Y., Zhang J., Jiang K., Pendry J. & Zhang S. Macroscopic invisibility cloaking of visible light. Nat. Commun. 2, 176 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ergin T., Fischer J. & Wegener M. Optical phase cloaking of 700 nm light waves in the far field by a three-dimensional carpet cloak. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 173901 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. H. et al. Direct visualization of optical frequency invisibility cloak based on silicon nanorod array. Opt. Express 17, 12922-12928 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gharghi M. et al. A carpet cloak for visible light. Nano Lett. 11, 2825-2828 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamma V. A., Blair J., Summers C. J. & Park W. Dispersion characteristics of silicon nanorod based carpet cloaks. Opt. Express 18, 25, 25746-25756 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Liu L., Luo Y., Zhang S. & Mortensen N. A. Homogeneous optical cloak constructed with uniform layered structures. Opt. Express 19, 9, 8625-8631 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X. et al. Broad band invisibility cloak made of normal dielectric multilayer. Appl. Phys. Lett. 99, 154104 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Cummer S. A., Popa B.-I., Schurig D., Smith D. R. & Pendry J. Full-wave simulations of electromagnetic cloaking structures. Phys. Rev. E 74, 036621 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai W., Chettiar U. K., Kildishev A. V. & Shalaev V. M. Optical cloaking with metamaterials. Nat. Photon. 1, 224-227 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y. et al. A rigorous analysis of plane-transformed invisibility cloaks. IEE Trans. Antenn. Propag. 57, 3926-3933 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Xi S., Chen H., Wu B.-I. & Kong J. A. One directional perfect cloak created with homogeneous material. IEEE Microw. Wirel. Compon. Lett. 19, 131-133 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Tretyakov S., Alitalo P., Luukkonen O. & Simovski C. Broadband electromagnetic cloaking of long cylindrical objects. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 103905 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards B., Alu A., Silveirinha M. G. & Engheta N. Experimental verification of plasmonic cloaking at microwave frequencies with metamaterials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 153901 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanté B., Germain D. & Lustrac A. Experimental demonstration of a nonmagnetic metamaterial cloak at microwave frequencies, .Phys. Rev. B. 80, 201104R (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Guan J., Sun Z., Wang W. & Zhang Q. A near perfect invisibility cloak constructed with homogeneous materials, .Opt. Express 17, 26, 23410-23416 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han T., Qiu C. & Tang X. An arbitrarily shaped cloak with nonsingular and homogeneous parameters designed using a twofold transformation, .J. Opt. 12, 095103 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Schurig D., Pendry J. B. & Smith D. R. Calculation of material properties and ray tracing in transformation medium. Opt. Express 14, 9794-9804 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B. et al. Response of a cylindrical invisibility cloak to electromagnetic waves. Phys. Rev. B 76, 121101R (2007). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Broadband polygonal invisibility cloak for visible light__Supplementary Information