Abstract

The extent of HIV-1 diversity was examined among patients attending a rural district hospital in a coastal area of Kenya. The pol gene was sequenced in samples from 153 patients. Subtypes were designated using the REGA, SCUEAL, and jpHMM programs. The most common subtype was A1, followed by C and D; A2 and G were also detected. However, a large proportion of the samples was found to be recombinants, which clustered within the pure subtype branches. Phylogeographic analysis of Kilifi sequences compared with those from other regions of Africa showed that while many sequences were closely related to sequences from Kenya, others were most closely related to known sequences from other parts of Africa, including West Africa. Overall, these data indicate that there have been multiple introductions of HIV-1 into this small rural town and surroundings with ongoing diversity being generated by recombination.

HIV-1 is composed of four groups (M, N, O, and P) with HIV-1 M being much the most common infection. The HIV-1 M group is subdivided into nine pure subtypes (A–D, F, G, H, J, and K), some of which may be further subdivided into subsubtypes (e.g., A1, A2).1 There is considerable geographic influence on circulating subtypes with some countries having a very high proportion of infections of a single subtype, for example, HIV-1 in North America is predominantly subtype B while subtype C predominates in Southern Africa. However, multiple subtypes coexist in populations and this can lead to the generation of intersubtype recombinant forms.

It has been postulated that HIV-1 subtypes A and D were introduced into East Africa after 1950 and spread exponentially during the 1970s, with the rapid spread in part being due to the strong interconnectivity between major population centers in the area.2 Studies in Kenya, mainly based in Nairobi, have confirmed the predominance of subtype A with subtype D being much less common, with occasional other subtypes and recombinants being detected.3,4 In a full genome characterization of 41 strains from blood donors in 1999–2000 it was found that 25 (61%) were pure subtype (23 A1, 1 C, and 1 D) and the rest intersubtype recombinants of which A1-D was predominant (15%) then A2-D and A1-C (both 7%) with A1-A2-D, A1-C-D, A1-G, and C-D also found.5

It has previously been reported that using a fragment of env gene of 86 samples from the Kenyan coastal strip, including 27 samples from Kilifi, 86% of samples were subtype A1, 5% were subtype C, 8% were subtype D, and 1% was subtype G.6 Full-length genome sequencing of samples from 21 individuals from Mombasa found that 74% of 23 isolates had pure subtype A strains while the rest were recombinants, including A-D, D-G, A-C, and A-A2-C-D.7

Here we report on the subtype diversity of HIV-1 infections among patients attending the comprehensive care and research clinic (CCRC, HIV clinic) at Kilifi District Hospital (KDH), Kenya, looking at pol gene sequences from 153 individuals attending the clinic. We confirm the predominance of subtype A1 but also report the presence of multiple other subtypes (A2, C, D, G) together with many novel recombinants. We further analyze the phylogeography of the sequences and show that there have been multiple introductions of HIV-1 into the area.

Kilifi is a small town serving a mainly rural population of about 250,000 in coastal Kenya about 50 km north of Mombasa. It lies on the main coastal tarmac road between Mombasa and Somalia, at a crossing point of the estuary of the Kilifi River, with most of the population being rural subsistence farmers. The prevalence of HIV-1 in the coastal province of Kenya in 15–49 year olds is estimated at 8.1% (male 6.7%, female 8.9%).8 KDH is a government hospital that has been providing comprehensive HIV services including free antiretroviral therapy (ART) and prevention of mother-to-child transmission since 2004. At the end January 2010, 2618 patients were on active follow-up in the HIV clinic, 47% of whom were on ART.

All samples were collected from attendees at the HIV clinic between July 2008 and June 2009, and were either new diagnoses (n=121) or patients undergoing treatment with ART (n=32). Overall, 72% of patients were female and 23% were children.

Population sequencing of 1245 nucleotides was carried out on PCR amplicons to give sequence for codons 5–99 of protease and 1–320 of reverse transcriptase using in-house methods. The sequences have accession numbers HQ441597–HQ441749. The sequences were manually aligned using the sequence editor Se-Al v2.0 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/seal/). Subtypes were assigned to the sequences using three methods: SCUEAL,9 using the default reference sequences, REGA version 2.0 (http://dbpartners.stanford.edu/RegaSubtyping/), and jpHMM.10 With all three methods, the default settings, including window size, were used. SCUEAL subtype designations of A or ancestral A were called A1, based on the phylogenetic clustering.

Considerable complexity was observed in the subtypes of the samples, with 42/153 (27%) of the samples not giving concordant results using all three methods. However, by all methods subtype A1 was the most common, comprising 54% of samples by SCUEAL, 59% by jpHMM, and 61% by REGA. The next most common subtypes were C, 8% by SCUEAL and jpHMM and 9% by REGA, and D, 9% by SCUEAL and REGA and 10% by jpHMM. The jpHMM analysis did not detect any pure A2 sequences whereas 1% by SCUEAL and 9% by REGA of samples were found to be A2, although there were no samples found to be A2 by both these latter methods. One sample was designated subtype G by all three methods. The rest of the samples were intersubtype recombinants (27% by SCUEAL, 23% by jpHMM, and 12% by REGA). The subtype designations by all three methods are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Subtype Designations by SCUEAL, REGA, and jpHMM

| Subtype | Frequency by SCUEAL % (n) | Frequency by REGA % (n) | Frequency by jpHMM % (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 54% (82) | 61% (93) | 59% (90) |

| A1-AE recombinant | 1% (2) | ||

| A1-C recombinant | 1% (2) | 2% (3) | 2% (3) |

| A1-D recombinant | 7% (10) | 5% (8) | 7% (11) |

| A1-unknown | <1% (1) | ||

| A1-A2 recombinant | 1% (2) | 1% (2) | |

| A1-A2-unknown | 1% (2) | ||

| A1-A2-B | 1% (2) | ||

| A1-A2-D recombinant | 2% (3) | ||

| A2 | 1% (2) | 9% (13) | |

| A2-B | 2% (3) | ||

| A2-D recombinant | 3% (4) | 3% (5) | |

| AE-C recombinant | <1% (1) | ||

| B-C recombinant | <1% (1) | ||

| C | 8% (12) | 9% (14) | 8% (13) |

| C-D recombinant | <1% (1) | 2% (3) | <1% (1) |

| C-unknown | <1% (1) | ||

| CRF16-like | 3% (5) | ||

| Complex | 10% (16) | <1% (1) | |

| D | 9% (14) | 9% (14) | 10% (16) |

| D-unknown | |||

| G | <1% (1) | <1% (1) | <1% (1) |

| Unknown | <1% (1) |

Intersubtype recombinants detected by the various methods included A1-AE, A1-A2, A1-A2-B, A1-A2-D, A1-C, A1-D, A2-B, A2-D, AE-C, B-C, C-D, and CRF-16-like. Concordance between all three methods as to the constituents of the recombinant sequences was present for only eight samples. The detection of subtype B sequences in five sequences by jpHMM and in one by SCUEAL was surprising given the rarity of subtype B in Africa, though the lack of agreement between the methods in the detection of this subtype possibly indicates that this was an artifact. In addition, some recombinants were designated as “complex” or had regions that were not classified and where there was a lack of high confidence in the subtype designations and breakpoints. These sequences included multiple subtypes and may be the consequence of further recombination between recombinants.

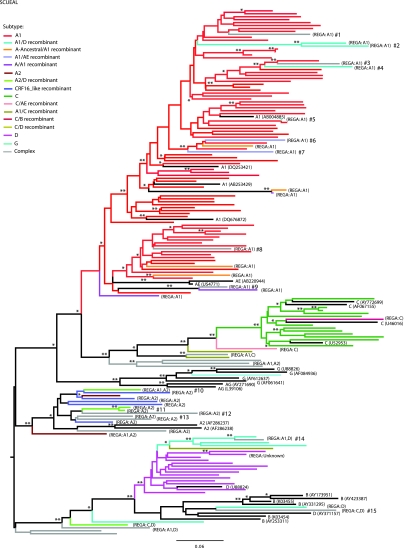

The phylogeny of the 153 Kilifi sequences together with HIV-1 subtype A1, A2, B, C, D, G, CRF01_AE, and CRF02_AG reference sequences from the Los Alamos HIV sequence database (http://www.hiv.lanl.gov/) was reconstructed using the program MrBayes v.3.1.2,11 under the general time reversible (GTR) model of nucleotide substitution with gamma-distributed rate heterogeneity. The GenBank accession numbers of the Los Alamos reference sequences are as follows: A (AB004885, AB253429, DQ253421, DQ676872), A2 (AF286237, AF286238), B (AY173951, AY253311, AY331295, AY423387, K03454, K03455), C (AF067155, AY772699, U46016, U52953), D (AY371157, U88824), G (AF061641, AF084936, AY612637, U88826), AE (AB220944, U54771), and AG (AY271690, L39106). The Bayesian Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) search was set to 8,000,000 iterations, with trees sampled every 100th generation. Convergence of the estimates was determined with the software Tracer v1.5 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/tracer/), as indicated by an effective sampling size of >200. A maximum clade credibility tree (MCCT) was selected from the sampled posterior distribution with the program TreeAnnotator version 1.5.2 (http://beast.bio.ed.ac.uk/), after discarding trees corresponding to a 20% burn-in. The MCCT Tree was edited with the program FigTree version 1.1.2 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/).

Figure 1 shows the relatedness of the sequences derived from patients from Kilifi to each other and to pure subtype sequences from the Los Alamos database, along with an indication of their subtype designation according to SCUEAL. There are large clusters mostly corresponding to the samples' subtype designation, i.e., A1, A2, C, and D, but most of the subclusters show sequence variability greater than 5% indicating multiple separate introductions of viruses. Surprisingly, sequences designated as A1 and A2 did not group together in the tree, as would be expected from subsubtypes. Only four pairs of sequences clustered very closely together, indicating being related by close transmission events (pairwise genetic distance <0.015 substitutions per nucleotide site and Bayesian posterior probability of 1.00). These include two pairs of A1 sequences, one pair of an A2-D recombinant, and one pair of subtype C sequences. Within each subtype cluster there were also many recombinant viruses, but close relationships between the recombinants were seldom seen (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Phylogeny of the 153 HIV-1 isolates from Kilifi. A maximum clade credibility tree was retrieved from a posterior distribution of Bayesian MCMC 10,000 trees, under the GTR+G model of nucleotide substitution. Branches are colored according to the HIV-1 subtype assigned by the program SCUEAL. HIV subtype reference sequences are indicated in black, with the corresponding GenBank accession number. Differences with REGA subtype assignations are indicated in brackets. Bayesian posterior probabilities of 1.00 and above 0.90 are shown on the branches by two asterisks and one asterisk, respectively. Discordant sequences are indicated as #1 to #14. Branch lengths indicate the number of substitutions per nucleotide sites. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/aid

Many of the recombinants picked up by SCUEAL or jpHMM were “sporadic,” i.e., they stemmed from a region of pure subtype, and had unique recombination patterns. Thus, some clusters with high statistical support in the tree in Fig. 1 contained sequences of different subtypes, including complex recombinants. In Fig. 1, these “discordant” sequences are indicated by a hash sign (#) and their deduced major parental subtype is shown in Table 2. These are possibly indicative of de novo recombination. Some of these sporadic samples, such as discordant sequence #14, arose out of clusters of recombinant viruses, e.g., A1-D, and showed evidence of further subtype sequence. By SCUEAL this mosaic sequence contained C, CRF21, D, and A2 sequences and by REGA, C and D. Thus it appears that the “sporadic” recombinants were mosaics between an older recombinant form and another subtype.

Table 2.

Subtype Origin of Discordant Clusters

| |

Discordant clusters (indicated on the tree)a |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of sequences | Subtypeb | Parent subtype | Supportc | |

| #1 | 1 | Complex | A1 | 0.46 |

| #2 | 2 | Both A1-D | A1 | 1.00 |

| #3 | 1 | Complex | A1 | 0.96 |

| #4 | 1 | A1-D | A1 | 0.70 |

| #5 | 1 | A1 | A1 | 1.00 |

| #6 | 1 | A1-AE | A1 | 1.00 |

| #7 | 1 | A1-AE | A1 | 1.00 |

| #8 | 1 | Complex | A1 | 0.93 |

| #9 | 1 | Complex | A1 | 1.00 |

| #10 | 1 | A2-D | A2 | 0.98 |

| #11 | 2 | Both A2-D | A2 | 0.99 |

| #12 | 1 | Complex | A2 | 0.99 |

| #13 | 2 | Complex | A2 | 0.99 |

| #14 | 1 | Complex | A1-D | 1.00 |

| #15 | 1 | Complex | A1-D | 0.78 |

Recombinants with no obvious parent cluster (i.e., singletons) were excluded.

A_Ancestral/A1 and A1/A recombinants are considered as A1.

Bayesian posterior probability of the cluster comprising the recombinant sequence.

To investigate the migration patterns of the Kilifi isolates, phylogeographic analyses were conducted using the Bayesian probabilistic model developed by Lemey et al.12 The Kilifi sequences were grouped per subtype and compared to HIV-1 pol genes sequences of African origin available on the Los Alamos HIV sequence database (http://www.hiv.lanl.gov/content/index). These comprised 226 subtype A sequences, 170 subtype C sequences, 73 subtype D sequences, 21 subtype G sequences, 216 CRF16-like sequences, and 180 A-like complex recombinant forms. Each sequence was assigned a geographic state corresponding to its country of sampling, and ancestral state reconstruction along the sequences' phylogeny was performed using the program BEAST version 1.5.2.13 Trees were reconstructed under the General Time Reversible model of nucleotide substitution with gamma-distributed rate heterogeneity, a relaxed molecular clock, and a Bayesian Skyline coalescent prior. The Bayesian MCMC searches were set to 3,000,000 iterations, with trees sampled every 1000th generation. Maximum clade credibility trees (MCCTs) were selected as described above. For each subtype-specific MCCT tree, phylogenetic clusters supported by a Bayesian posterior probability >90 were considered significant, and the most probable origin of clusters including one or more Kilifi sequence was recorded when associated with a Bayesian probability of 0.95 or more.

The sequences described here were compared with sequences of African origin from the Los Alamos database in order to determine the most likely geographic origin of the nearest related strain. Overall, 112/153 (73%) of the sequences could be linked to other sequences in the database derived from Kenyan samples. Choosing a Bayesian probability of 0.95 for the assignment of the most probable origin of a cluster gave the following results:

Subtype A1: eight/nine clusters with a Kenyan origin (probability 0.99 or 1.00), three of which also included sequences from Uganda, one from Tanzania, and one from Senegal. Subtype A2: Two samples lay in separate clusters on the tree, none of which had a geographic match. Subtype C: There were five separate Kilifi clusters, two of which had either a Kenyan (probability 0.99) or Tanzanian (probability 0.96) origin, while the remaining three clusters had no close geographic link. Subtype D: Of nine clusters only one had a Kenyan origin (probability 0.97). Subtype G: there was no strongly supported geographic match. Thus, overall, most A1 sequences appeared to have originated in Kenya while many of the other strains had widely dispersed or unknown origins.

The study reported here confirms and extends the observations that the HIV-1 epidemic in Kenya is highly diverse. It would appear that even within a relatively small geographic area (∼900 km2), with a population of about 250,000 served by one main HIV clinic, there have been (and probably still are) many separate introductions of the virus. Multiple subtypes were detected and for many they apparently originated elsewhere in Africa (including Senegal, Botswana, Tanzania, Zaire, and other parts of Kenya). Not surprisingly, given such a melting pot of infections, numerous recombinant forms of the virus were also detected.

The designation of subtypes for these samples was challenging due to the large numbers of recombinants, most previously not described. There was some disagreement between the three methods used to determine the subtypes, particularly where one program designated the sequence as a recombinant, possibly reflecting differences in the reference sequences used by the programs. In addition, it was found that SCUEAL did not always provide the same output when highly complex recombinant sequences were repeatedly tested, probably due to SCUEAL being a randomized algorithm.

The phylogeographic analysis of these sequences showed that many were related to previously described samples from Kenya, particularly those of the A1 subtype. However, a substantial proportion showed clustering with strains from elsewhere in Africa including Senegal in West Africa, or else had no close match with African sequences in the Los Alamos database. This may be a reflection of the extensive transport links from Kilifi by road and railway (from Mombasa) into the center of Africa via Nairobi and then onward to Kampala and Rwanda and also along the coast, since the distribution of HIV-1 in East Africa has been postulated to be associated with transport links.2 In addition, Mombasa is a major port with extensive worldwide shipping links. It is likely that there will be a continuing importation of new strains of HIV-1 into the area resulting in the emergence of yet more complex recombinants.

Sequence Data

The sequences reported in this paper have accession numbers HQ441597–HQ441749.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Bharati Patel, Josephine Morris, and Lisa Ryan of HPA Microbiological Services Division, Colindale, for undertaking the sequencing. We thank all the staff of the Comprehensive Care and Research Clinic (CCRC) at Kilifi District Hospital for assisting in coordinating sample collection and providing clinical care. This article is published with the approval of the Director of KEMRI. A.H. and J.B. are funded by the Wellcome Trust, UK. D.P. and S.H. are funded through the NIHR UCLH/UCL Comprehensive Biomedical Research Centre and the European Community's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under the project “Collaborative HIV and Anti-HIV Drug Resistance Network (CHAIN),” Grant 223131. E.J.S. is financially supported through the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative. P.A.C. is funded by the Health Protection Agency, UK.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Robertson DL. Anderson JP. Bradac JA. Carr JK. Foley B. Funkhouser RK. Gao F. Hahn BH. Kalish ML. Kuiken C. Learn GH. Leitner T. McCutchan F. Osmanov S. Peeters M. Pieniazek D. Salminen M. Sharp PM. Wolinsky S. Korber B. HIV-1 nomenclature proposal. Science. 2000;288(5463):55–56. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5463.55d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gray RR. Tatem AJ. Lamers S. Hou W. Laeyendecker O. Serwadda D. Sewankambo N. Gray RH. Wawer M. Quinn TC. Goodenow MM. Salemi M. Spatial phylodynamics of HIV-1 epidemic emergence in east Africa. AIDS. 2009;23:F9–F17. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832faf61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lihana RW. Khamadi SA. Kiptoo MK. Kinyua JG. Lagat N. Magoma GN. Mwau MM. Makokha EP. Onyango V. Osman S. Okoth FA. Songok EM. HIV type 1 subtypes among STI patients in Nairobi: A genotypic study based on partial pol gene sequencing. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2006;22:1172–1177. doi: 10.1089/aid.2006.22.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lihana RW. Khamadi SA. Lwembe RM. Ochieng W. Kinyua JG. Kiptoo MK. Muriuki JK. Lagat N. Osman S. Mwangi JM. Okoth FA. Songok EM. The changing trend of HIV type 1 subtypes in Nairobi. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2009;25:337–342. doi: 10.1089/aid.2008.0228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dowling WE. Kim B. Mason CJ. Wasunna KM. Alam U. Elson L. Birx DL. Robb ML. McCutchan FE. Carr JK. Forty-one near full-length HIV-1 sequences from Kenya reveal an epidemic of subtype A and A-containing recombinants. AIDS. 2002;16:1809–1820. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200209060-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khamadi SA. Lihana RW. Osman S. Mwangi J. Muriuki J. Lagat N. Kinyua J. Mwau M. Kageha S. Okoth V. Ochieng W. Okoth FA. Genetic diversity of HIV type 1 along the coastal strip of Kenya. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2009;25:919–923. doi: 10.1089/aid.2009.0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tovanabutra S. Sanders EJ. Graham SM. Mwangome M. Peshu N. McClelland RS. Muhaari A. Crossler J. Price MA. Gilmour J. Michael NL. McCutchan FM. Evaluation of HIV type 1 strains in men having sex with men and in female sex workers in Mombasa, Kenya. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2010;26:123–131. doi: 10.1089/aid.2009.0115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National AIDS and STI Control Programme (NASCOP), Ministry of Health, Kenya. Kenya AIDS indicator survey 2007: full report Nairobi. Kenya: NASCOP; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kosakovsky Pond SL. Posada D. Stawiski E. Chappey C. Poon AF. Hughes G. Fearnhill E. Gravenor MB. Leigh Brown AJ. Frost SD. An evolutionary model-based algorithm for accurate phylogenetic breakpoint mapping and subtype prediction in HIV-1. PLoS Comput Biol. 2009;5(11):e1000581. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schultz A-K. Zhang M. Bulla I. Leitner T. Korber B. Morgenstern B. Stanke M. jpHMM: Improving the reliability of recombination prediction in HIV-1. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:W647–651. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ronquist F. Huelsenbeck JP. MRBAYES 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1572–1574. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lemey P. Rambaut A. Drummond AJ. Suchard MA. Bayesian phylogeography finds its roots. PLoS Comput Biol. 2009;5(9):e1000520. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drummond AJ. Rambaut A. “BEAST: Bayesian evolutionary analysis by sampling trees.”. BMC Evol Biol. 2007;7:214. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-7-214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]