Abstract

The Green Revolution dwarfing genes, Rht-B1b and Rht-D1b, encode mutant forms of DELLA proteins and are present in most modern wheat varieties. DELLA proteins have been implicated in the response to biotic stress in the model plant, Arabidopsis thaliana. Using defined wheat Rht near-isogenic lines and barley Sln1 gain of function (GoF) and loss of function (LoF) lines, the role of DELLA in response to biotic stress was investigated in pathosystems representing contrasting trophic styles (biotrophic, hemibiotrophic, and necrotrophic). GoF mutant alleles in wheat and barley confer a resistance trade-off with increased susceptibility to biotrophic pathogens and increased resistance to necrotrophic pathogens whilst the converse was conferred by a LoF mutant allele. The polyploid nature of the wheat genome buffered the effect of single Rht GoF mutations relative to barley (diploid), particularly in respect of increased susceptibility to biotrophic pathogens. A role for DELLA in controlling cell death responses is proposed. Similar to Arabidopsis, a resistance trade-off to pathogens with contrasting pathogenic lifestyles has been identified in monocotyledonous cereal species. Appreciation of the pleiotropic role of DELLA in biotic stress responses in cereals has implications for plant breeding.

Keywords: Biotroph/necrotroph, DELLA, Green Revolution, Hordeum vulgare L., polyploidy, Reduced height (Rht), resistance trade-off, Slender 1 (Sln1), Triticum aestivum L

Introduction

The introduction of the Reduced height (Rht) genes (Rht-B1b and Rht-D1b alleles) underpinned the increases in wheat yields that occurred during the ‘Green Revolution’ and they continue to be used in most modern varieties (Hedden, 2003). These alleles are less sensitive to the phytohormone, gibberellin (GA), than their wild-type counterparts (Rht-B1a and Rht-D1a) resulting in a reduction in stem elongation. The yield benefits associated with these alleles arise from increased resistance to lodging when additional nitrogen is applied to varieties carrying these alleles and an altered harvest index whereby a greater proportion of the plant biomass is partitioned into the grain.

Rht-B1 and Rht-D1 encode DELLA proteins (Peng et al., 1999), which act to repress GA-responsive growth, and the Rht-B1b and Rht-D1b mutations are thought to confer dwarfism by producing constitutively active forms of these growth repressors (Peng et al., 1999). Most of our knowledge of DELLA genes derives from studies on Arabidopsis thaliana. The Arabidopsis genome contains five DELLA genes that encode distinct proteins (GAI, RGA, RGL1, RGL2, and RGL3; Peng et al., 1997; Silverstone et al., 1998; Wen and Chang, 2002). DELLA proteins are nuclear localized repressors of growth that are core components of the GA signal transduction pathway (Peng et al., 1997). In the presence of GA, DELLA interacts with the soluble GA receptor, GIBBERELLIN INSENSITIVE DWARF1, GID1 (Ueguchi-Tanaka et al., 2005) and the F-box protein SLY1/GID2, leading to the polyubiquitination, and subsequent degradation of DELLA protein by the 26S proteasome (Ueguchi-Tanaka et al., 2007). In addition to their role in plant development, recent studies in Arabidopsis have implicated DELLA proteins in resistance to biotic stress (Navarro et al., 2008), suggesting that DELLA encoding genes have a role in disease resistance.

Depending on their mode of infection, plant pathogens can be broadly classified into three trophic lifestyles; biotrophs, necrotrophs, and hemibiotrophs. Biotrophs derive nutrients from living cells whilst necrotrophs kill host cells in order to derive energy (Lewis, 1973). A hemibiotrophic pathogen requires an initial biotrophic phase before switching to necrotrophy to complete its life cycle (Perfect and Green, 2001). When subjected to pathogen attack, a plant is required to respond appropriately. An interplay between the phytohormones salicylic acid (SA), jasmonic acid (JA), and ethylene (ET) activates distinct defence pathways, depending on the lifestyle of the invading pathogen (Glazebrook, 2005). The antagonistic cross-talk between the SA and JA/ET signalling pathways enhances resistance to biotrophic and necrotrophic pathogens, respectively. Navarro et al. (2008) suggested that DELLA proteins differentially affect responses to biotrophic and necrotrophic pathogens through their influence on the SA–JA balance. Accumulation of DELLA results in potentiated JA signalling and, consequently, to a dampening of SA signalling. Accordingly, in DELLA accumulating mutants, resistance to necrotrophs in Arabidopsis is enhanced, and resistance to biotrophs is reduced.

In contrast to Arabidopsis, monocot cereal species appear to contain a single DELLA encoding gene. The Reduced height (Rht) gene of Triticum aestivum (bread wheat) and the Slender 1 (Sln1) gene of Hordeum vulgare (barley) are both orthologous to GAI (Peng et al., 1999; Chandler et al., 2002). Mutations disrupting the conserved DELLA domain, essential for GID1 interaction, reduce the susceptibility of DELLA to GA-induced degradation (Peng et al., 1999; Chandler et al., 2002) and result in a dwarf phenotype, a trait which has been exploited by wheat breeders, for example, Rht-B1b and Rht-D1b.

Reduced height in wheat has been associated with increased susceptibility to splash dispersed pathogens (Vanbeuningen and Kohli, 1990; Eriksen et al., 2003; Gervais et al., 2003; Draeger et al., 2007; Klahr et al., 2007). This was thought to be due to the reduced distances between consecutive leaves facilitating progress of the pathogen (the ‘ladder effect’, Bahat et al., 1980) and to alterations in canopy structure providing a micro-climate more favourable for pathogen establishment (Scott et al., 1982, 1985). However, not all plant height QTL are coincident with those for pathogen susceptibility, as has been demonstrated with fusarium head blight (FHB; Draeger et al., 2007), suggesting that resistance is not an effect of height per se but rather of linkage or pleiotropy. Significantly, the Rht-B1 and Rht-D1 loci on chromosome 4B and 4D, respectively, are coincident with FHB resistance loci suggesting that they may have a pleiotropic effect on susceptibility to FHB (Srinivasachary et al., 2009).

The relative resistance of both wheat and barley lines, differing in DELLA status, against cereal fungal pathogens, representing each of the three classes of pathogen lifestyle, was assessed here. Barley was used to study the effect of DELLA (Sln1) gain of function (GoF) and loss of function (LoF) mutants in a diploid species. The effect of Rht in hexaploid wheat was also investigated using GoF mutants of differing severity originating from different sources. In combination the results suggest that DELLA confers a pleiotropic effect on disease resistance which may in part be due to DELLA’s role in the control of cell death.

Materials and methods

Plant material

Near-isogenic lines (NILs) of wheat (Triticum aestivum) varieties Mercia, Maris Huntsman, and April Bearded differing in the alleles at the Reduced height (Rht) loci on chromosome 4B and 4D were kindly supplied by Dr J Flintham of the John Innes Centre, Norwich, England. The semi-dwarf GoF alleles Rht-B1b and Rht-D1b (formerly Rht1 and 2) and the severe dwarf alleles Rht-B1c and Rht-D1c (formerly Rht3 and 10, respectively) are dominant gibberellin-(GA) insensitive alleles which are thought to accumulate DELLA to higher levels than the wild type (Peng et al., 1999) while the wild type (rht-tall) parental lines carry GA-sensitive alleles at all three homoeologous loci (Flintham et al., 1997). The severe dwarf allele, Rht-B1c, is a result of an insertion in Rht-B1 and Rht-D1c results from a gene duplication of Rht-D1 (Pearce et al., unpublished results), in both cases probably resulting in an increase in DELLA accumulation. Barley (Hordeum vulgare) variety Himalaya, the dwarf (GoF) mutant (M640), and the constitutive growth (LoF) mutant (M770) were kindly supplied by Dr P Chandler of CSIRO, Canberra, Australia. M640 carries a dominant GA-insensitive allele (Sln1d) at the Slender 1 (Sln1) locus that is orthologous to Rht of wheat (Chandler et al., 2002). The LoF mutant M770 contains an early termination codon at the Sln1 locus, resulting in a truncated protein lacking the COOH-terminal 17 amino acid residues. This loss of function allele has been designated sln1c. In the homozygous state, the loss of functional DELLA results in male sterility and therefore homozygous sln1c/sln1c plants have to be selected in a 1:3 ratio from a heterozygous parent. All of the lines used in this study are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of plant material used

| Species | Locus | Allele | Phenotype | Origin |

| Triticum aestivum | Rht-B1 | rht-tall | Wild type | – |

| Rht-B1b (Rht 1) | Semi-dwarf | cv. Norin 10—nucleotide substitutiona | ||

| Rht-B1c (Rht 3) | Severe-dwarf | cv. Tom Thumb—insertionb | ||

| Rht-D1 | rht-tall | Wild type | – | |

| Rht-D1b (Rht 2) | Semi-dwarf | cv. Norin 10—nucleotide substitutiona | ||

| Rht-D1c (Rht 10) | Severe-dwarf | cv. Aibian—gene duplicationb | ||

| Hordeum vulgare | Sln1 | WT | Wild type | – |

| Sln1d | Dwarf (GoF) | cv. Himalaya—point mutationc | ||

| sln1c | Slender (LoF) | cv. Himalaya—point mutationc |

Influence of DELLA alleles on resistance of wheat and barley to Blumeria graminis

Near-isogenic lines of wheat cvs Mercia (rht-tall, Rht-B1c, and Rht-D1c), Maris Huntsman (rht-tall, Rht-B1c, and the double mutant Rht-B1c+D1b), and April Bearded (rht-tall and the double mutant Rht-B1c+D1b), and barley cv. Himalaya WT, Sln1d, and sln1c plants were grown to growth stage (GS) 12 (Zadoks et al., 1974; i.e. second seedling leaf as long as the prophyll) in controlled environment cabinets under a 16 h photoperiod and a 17/12 °C day/night temperature regime. Detached sections (2.5 cm) of the second leaf were placed in agar boxes and inoculated with the spores of virulent Blumeria graminis isolates (f. sp. tritici (Bgt) or f. sp. hordei (Bgh) for wheat and barley, respectively) as described by Brown and Wolfe (1990). Experiments were conducted in a randomized block design of four replicates with four detached leaves of each line per replicate. Each experiment was repeated three times.

Bgh inoculated barley leaves were collected at 48 h and 60 h post-inoculation (hpi) for microscopic analysis. Leaf tissue was cleared and fungal structures were scored for papillae defence and host cell death response at each time point as described by Boyd et al. (1994a). One-hundred interaction sites were observed across four leaves per genotype. Fungal structures and plant cellular autofluorescence were observed using a Nikon Microphot-SA with Nomarski (DIC) and a fluorescence filter; FITC (450–490 nm >520LP). In this study, a successful interaction was scored if the fungus developed an haustorium. The stages of Bgh development are well defined (Boyd et al., 1994b), balloon/digitate haustoria form within the epidermal cells and hyphal development follows. The stage to which infection progressed was scored for each interaction. Macroscopic symptoms were assessed at 8 d post-inoculation (dpi) by quantifying colonies cm−2 of leaf area of 12 leaves per genotype.

Influence of DELLA alleles on resistance of barley to Ramularia collo-cygni

Barley cv. Himalaya WT and Sln1d were grown and inoculated with R. collo-cygni according to the methods reported previously by Makepeace et al. (2008). This experiment was conducted in a randomized block design with three blocks each containing five plants per line. Symptoms were assessed at 15 dpi as the percentage of leaf area covered with lesions. This experiment was repeated three times with the addition of sln1c in the third experiment.

Influence of DELLA alleles on resistance of wheat and barley to Oculimacula acuformis and O. yallundae

Wheat cv. Mercia rht-tall, Rht-B1c, and Rht-D1c NILs, and barley cv. Himalaya WT and Sln1d lines were grown and inoculated with either O. acuformis or O. yallundae as described by Chapman et al. (2008). Plants were harvested 6–8 weeks after inoculation and scored for fungal penetration of leaf sheaths according to the scale devised by Scott (1971). The experiments were conducted in a randomized block design with five blocks, each containing ten plants per line of which five were inoculated with O. acuformis and five were inoculated with O. yallundae. The experiment was repeated once to confirm the findings.

In a third experiment, Himalaya WT, Sln1d, and sln1c lines were inoculated with O. acuformis. Due to the elongated nature of the sln1c mutant line, the method described by Chapman et al. (2008) was modified by using longer tubes to contain the inoculum. This experiment was arranged in a randomized block design with five blocks as described above.

Influence of DELLA alleles on Type 1 resistance of wheat heads to Fusarium graminearum

Two independent experiments were carried out to assess resistance to initial infection [Type 1 resistance sensu Schroeder and Christensen (1963)]. In experiment 1, Mercia and Maris Huntsman NILs (rht-tall, Rht-B1b, and Rht-B1c) were grown in the field. Experiment 2 was conducted in an unheated polytunnel, only Mercia NILs (rht-tall, Rht-B1b, and Rht-B1c) were tested. In both experiments, lines were inoculated by spraying until run-off with a conidial suspension of F. graminearum (1×105 conidia ml−1) at GS 65 (Zadoks et al., 1974) as described previously by Gosman et al. (2005). Disease severity was visually assessed as the percentage of spikelets infected at 14 dpi. Experiment 1 was conducted in a randomized complete block design field trial with three replicate plots per line. Experiment 2 was conducted in a randomized complete block design consisting of four blocks within which were seven plants of each line.

Influence of DELLA alleles on Type 2 resistance of wheat and barley heads to Fusarium graminearum

Mercia and Maris Huntsman NILs (rht-tall, Rht-B1b, and Rht-B1c) were phenotyped in independent experiments for resistance to spread within the spike [Type 2 resistance sensu Schroeder and Christensen (1963)] in an unheated polytunnel. Experiments were arranged in a randomized complete block design with four replicate blocks with seven plants per line in each.

Inoculation and disease assessment were as described by Gosman et al. (2007). Lines were inoculated at GS 65 (Zadoks et al., 1974) by point inoculation with 50 μl of conidial suspension (1×106 ml−1) of a deoxynivalenol (DON) producing isolate of F. graminearum (UK1), injected into a single floret within the central portion of each spike. High humidity was maintained for 72 hpi by misting. Disease severity was measured as the number of diseased spikelets 14 dpi.

Influence of DELLA alleles on foliar disease resistance of wheat and barley to Fusarium graminearum

Plants of wheat cv. Maris Huntsman (rht-tall and Rht-B1c NILs) and barley cv. Himalaya (WT and Sln1d) were grown to GS 12 in controlled environment cabinets under a 16 h photoperiod and a 15/12 °C day/night temperature with 70% relative humidity. Sections (5 cm) of the second leaf were inoculated with conidia of F. graminearum (5 μl of 1×106 conidia ml−1) as described by Chen et al. (2009). Leaves were returned to the growth cabinet and lesion areas were measured after 6 d using ImageJ (Abramoff et al., 2004).

Influence of DELLA on resistance of wheat heads to deoxynivalenol

Maris Huntsman (rht-tall, Rht-B1b, and Rht-B1c) NILs were tested for resistance to DON in an unheated polytunnel. DON was kindly supplied by Dr M Lemmens (IFA-Tulln, Austria). At GS 65, two spikes per plant were treated with DON according to the method of Lemmens et al. (2005) with the following modification; DON solution was applied to a single clipped spikelet on each wheat head instead of two. Pots containing individual plants were arranged in a randomized complete block design of four replicates of seven plants per line. Following treatment, the number of damaged spikelets per head was assessed at 14 dpi.

Influence of DELLA on root growth of wheat and barley in response to deoxynivalenol

Seed of wheat cv. Maris Huntsman (rht-tall, Rht-B1b, and Rht-B1c NILs) and barley cv. Himalaya (WT and Sln1d) were germinated on 0.7% water agar and transferred to 90 mm Petri-dishes of water agar containing 25 μM DON or to new water agar dishes (controls) and incubated at 5 °C in the dark. Samples consisted of three replicate dishes of 20 germinated seeds per line. The lengths of primary roots were measured after a period of 10 d (experiment 1) or 14 d (experiment 2). The root length of seedlings grown on DON was expressed as a percentage of the average root length of their respective controls (mean relative length).

Influence of DELLA on deoxynivalenol-induced expression of negative cell death regulators

Maris Huntsman (rht-tall, Rht-B1b, and Rht-B1c) NILs were incubated in darkness at 20 °C for 5 d on moist filter paper. Roots were submerged in water or DON solution (50 μM) and incubated for 8 h prior to RNA extraction. Total RNA was isolated using Qiagen RNA easy spin columns from 100 mg of root tissue, ground in a pestle and mortar under liquid nitrogen. DNase treatment was carried out using the Turbo DNA-free kit (Ambion) and cDNA was synthesised from 5 μg of RNA using SuperScript III (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s instructions with the addition of random nonamers (50 μM, Invitrogen). RNA was digested with RNase-H (Invitrogen) from the RNA-DNA duplex to leave single-strand cDNA. cDNA was diluted 1:20 for qRT-PCR. qRT-PCR reactions were carried out using a DNA engine Opticon2 Continuous Fluorescence Detector (MJ Research Inc., Alameda, CA, USA). Amplification was carried out using SYBR Green Jumpstart Taq ready mix with gene-specific primers (BAX INHIBITOR-1 fwd – TACATGGTGTACGACACGCA and rev – GTCCATGTCGCCGTGG (accession: HM447649) and RADICAL-INDUCED CELL DEATH 1 fwd – GCGTCTGTCTGTGAATCTGC and rev – TGTTGATTGGACAAAAACCAA (Walter et al., 2008)). An initial activation step at 95 °C for 4 min was followed by 40 cycles of 30 s at 95 °C, 30 s at 60 °C, and 30 s at 72 °C. Target gene expression was calculated relative to the expression of the reference gene, 18S rRNA (fwd – AGTAAGCGCGAGTCATCAGCT and rev – CATTCAATCGGTAGGAGCGAC) using the ΔΔCT method (Pfaffl, 2001). cDNA was diluted 1:100 for the quantification of the expression of 18S rRNA.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using GenStat for Windows, 12th edition (Payne et al., 2009). For count data, a Poisson regression and for percentage data a logistic regression was used in a generalized linear model (GLM) to estimate variance attributable to replicate, experiment, and genotype. Means were compared using t-probabilities calculated within the GLM.

Results

Interaction between DELLA and Blumeria graminis

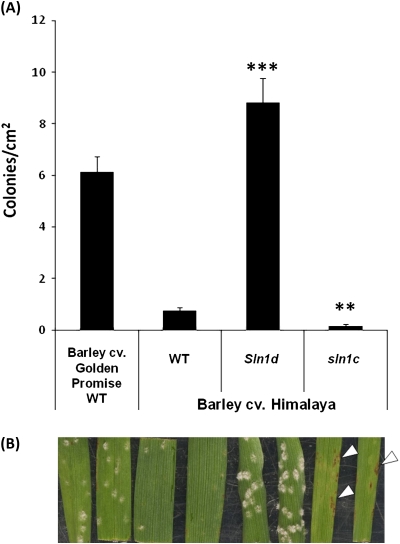

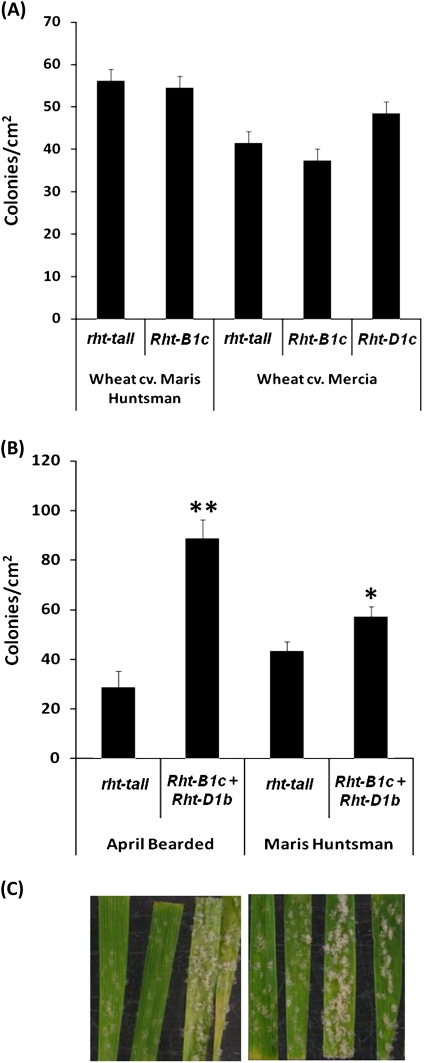

B. graminis f. sp. tritici (Bgt) and f. sp. hordei (Bgh) are obligate biotrophic fungi that infect wheat and barley, respectively, causing powdery mildew. The DELLA GoF barley line, Sln1d, showed a significant (P <0.001) increase in susceptibility to Bgh compared with the Himalaya wild type (Fig. 1A). Whilst the LoF DELLA mutant line, sln1c, was significantly (P <0.01) more resistant compared with the Himalaya wild type, which itself expressed a high level of resistance relative to the susceptible cultivar Golden Promise. The sln1c line exhibited a spreading hypersensitive cell death phenotype (Fig. 1B), which is absent in the other lines. The wild type and severe dwarf (Rht-B1c or Rht-D1c) NILs of Mercia and Maris Huntsman were equally infected by B. graminis (Fig. 2A). However, lines containing two copies of mutant alleles (the semi-dwarf and severe dwarfing alleles; Rht-B1c and Rht-D1b) were significantly (P <0.05) more susceptible (assessed as colonies cm−2) than the respective wild-type plants (Fig. 2B, C).

Fig. 1.

The effect of Sln1 alleles on infection of barley with B. graminis f. sp. hordei. (A) Leaves of barley cvs Golden Promise (susceptible control) and Himalaya allelic at the Sln1 locus inoculated with B. graminis f. sp. hordei. The number of colonies per leaf area (cm2) were measured 8 dpi. Bars ±1 SEM. ***, ** Significant difference (P <0.001 and P <0.01, respectively) from Himalaya wild type (WT). (B) Representative disease phenotypes, white arrow heads denote the hypersensitive response in sln1c.

Fig. 2.

The effect of GoF Rht alleles on infection of wheat with B. graminis f. sp. tritici. The number of colonies cm−2 at 8 dpi is presented for (A) wheat cvs Maris Huntsman and Mercia rht-tall (wild type) and severe dwarf NILs inoculated with B. graminis f. sp. tritici and (B) wheat cvs April Bearded and Maris Huntsman, rht-tall (wild type) and double mutant (Rht-B1c+Rht-D1b) NILs inoculated with B. graminis f. sp. tritici. Bars ±1 SEM. *, ** Significant difference (P <0.05 and P <0.01, respectively) from the respective wild type lines. (C) The representative disease phenotype of two detached leaves correspond to (B).

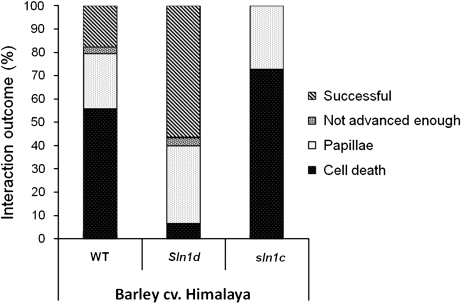

Cytological analysis of the barley lines showed that a significantly (P <0.001) higher proportion of spores infected plant host epidermal cells in Sln1d (57%) compared with WT Himalaya (18%), and none of the spores infected the cells of sln1c leaves. In the sln1c line, a high proportion (73%) of the unsuccessful interactions were due to host cell death. In Sln1d leaves, by contrast, a significantly (P <0.001) lower proportion (15%) of unsuccessful interactions were due to cell death restriction, with the majority attributable to papillae formation (77%, Fig. 3) and the remaining spores not being advanced enough to elicit either response. Interestingly, while the B. graminis-associated cell death differed significantly in a DELLA-dependent manner, restriction of the fungus by papillae formation alone was independent of the DELLA status of the line. Furthermore, the fungal colonization process was more rapid in the Sln1d interaction than in the wild type. By 60 hpi, all successfully infecting spores reached the hyphal stage on Sln1d whilst only 17% of successfully infecting spores had reached this stage on wild-type leaves, with most (83%) only at the balloon/digitate haustorium stage.

Fig. 3.

Cytological analysis of the effect of Sln1 alleles on infection of barley with B. graminis f. sp. hordei. The interaction outcome of 100 spores was analysed at 60 hpi. Spores which produced a haustorium were defined as successful. Unsuccessful interactions were attributed to either host cell death, papillae response or because spores were not advanced enough to elicit a response.

Interaction between DELLA and Ramularia collo-cygni

The responses of barley lines, differing in DELLA status, to the hemibiotroph Ramularia collo-cygni were assessed. R. collo-cygni is a barley infecting pathogen which exhibits a long biotrophic, endophytic phase before switching to a necrotrophic lifestyle late in infection (Stabentheiner et al., 2009). The DELLA GoF mutant, Sln1d was significantly (P <0.001) more susceptible (assessed as % diseased leaf area) to R. collo-cygni than the wild-type line. In a third experiment, the LoF DELLA mutant line, sln1c was included. Confirming the role of DELLA in increasing susceptibility to R. collo-cygni infection, the DELLA LoF mutant line was found to be significantly (P=0.03) more resistant than the wild-type line (Table 2).

Table 2.

The effect of Sln1 alleles on resistance to Ramularia collo-cygni assessed as % Diseased leaf area

| Genotype | % Diseased leaf area | SEM | P-value |

| WT | 6.4 | ±1.0 | |

| Sln1d | 14.1 | ±1.0 | <0.001 |

| sln1c | 1.0 | ±2.2 | 0.033 |

Interaction between DELLA and Oculimacula spp.

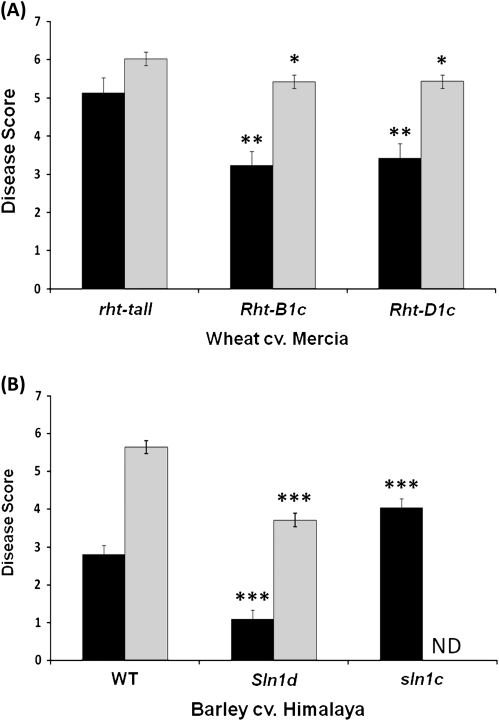

O. acuformis and O. yallundae infect the stem base of cereal hosts and present contrasting pathogenic lifestyles. The former is considered a necrotroph whilst there is evidence that the latter exhibits a short biotrophic phase of establishment before switching to necrotrophic nutrition (Blein et al., 2009). Wheat GoF severe dwarfing mutant lines, Rht-B1c and Rht-D1c, showed significantly greater resistance to both O. acuformis and O. yallundae (P <0.01 and P <0.05, respectively) compared with rht-tall lines (Fig. 4A). Interestingly, the disease resistance conferred by DELLA stabilisation was greater for the fully necrotrophic species O. acuformis than for O. yallundae which exhibits a short initial biotrophic phase. GoF mutants in barley also exhibited significantly (P <0.001) increased resistance to both forms of the disease relative to wild-type plants and in further support of the role of DELLA in disease resistance, the LoF DELLA mutant line sln1c exhibited significantly (P <0.001) greater susceptibility to O. acuformis (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

The effect of Rht and Sln1 alleles on resistance of wheat and barley to Oculimacula species. (A) Wheat cv. Mercia rht-tall (wild type) and severe dwarf NILs inoculated with either O. acuformis (black bars) or O. yallundae (grey bars) were scored for disease severity using a scale devised by Scott (1971). Bars ±1 SEM. *, ** Significant difference (P <0.05 and P <0.01, respectively) from Mercia rht-tall. (B) Barley cv. Himalaya WT, Sln1d and sln1c were scored and presented as above. The sln1c line was not inoculated with O. yallundae (ND; no data). Bars ±1 SEM. *** Significant difference (P <0.001) from Himalaya WT.

Interaction between DELLA and FHB caused by Fusarium graminearum

Fusarium graminearum is one of the predominant causes of FHB. While F. graminearum was, for a considerable period, thought to be entirely necrotrophic in lifestyle, it is now considered to exhibit a short biotrophic phase during the infection of wheat heads (Brown et al., 2010). Schroeder and Christensen (1963) describe two main components of resistance to FHB: resistance to initial infection (Type 1) and resistance to spread within the head (Type 2). These components can be broadly dissected using different inoculation techniques (Miedaner et al., 2003), namely spray or point inoculation.

Spray inoculation of wheat heads is generally used to assess the combined effects of Type 1 and Type 2, but scoring disease symptoms before the fungus begins to spread within the head provides a measure of Type 1 resistance, which includes the biotrophic phase of the interaction. Following establishment, F. graminearum switches to a necrotrophic mode during which it produces the mycotoxin deoxynivelenol (DON) that functions as a virulence factor in FHB of wheat facilitating the spread of the fungus within the head (Bai et al., 2002). Point inoculation of individual spikelets, which bypasses the plant’s defence against initial infection, is used to assess resistance to disease spread (Type 2 resistance).

Near-isogenic wheat lines were subjected to spray or point inoculation with conidia of F. graminearum. Following spray inoculation, rht-tall showed the greatest resistance to initial infection in both field and polytunnel experiments (Table 3). In both experiments the severe dwarf Rht-B1c NIL showed significantly greater (P <0.009) susceptibility to initial infection compared with the semi-dwarf Rht-B1b line.

Table 3.

The effect of Rht alleles on Type 1 resistance to Fusarium Head Blight assessed as % Spikelets infected

| Experiment | Genotype | % Spikelets infected | SEM | P-value |

| Field | rht-tall | 11.7 | ±2.1 | |

| Rht-B1b | 15.8 | ±2.1 | 0.185 | |

| Rht-B1c | 25.0 | ±2.1 | <.001 | |

| Polytunnel | rht-tall | 18.8 | ±0.9 | |

| Rht-B1b | 24.2 | ±1.0 | <.001 | |

| Rht-B1c | 35.9 | ±1.1 | <.001 |

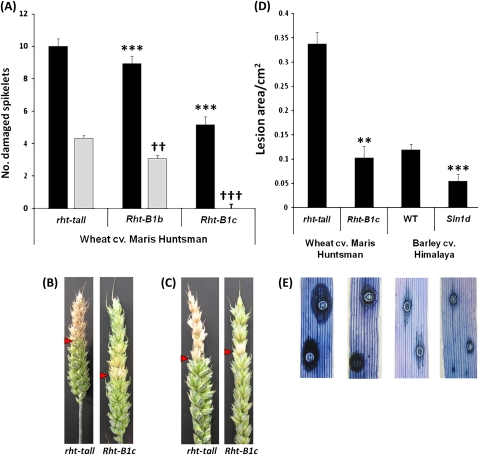

Following point inoculation, the wild-type line of Maris Huntsman was highly susceptible to the spread of F. graminearum with an average of 10.0 spikelets showing disease at 14 dpi (Fig. 5A, B). Rht-B1b NILs showed significantly less (P <0.001) symptom spread than the wild-type line, with an average of 8.9 spikelets showing disease at this stage. The reduction in symptoms was even greater for the Rht-B1c NILs with only 5.2 spikelets exhibiting disease (P <0.001). A similar trend was observed with Mercia wild-type, Rht-B1b, and Rht-B1c NILs (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

The effect of GoF mutant alleles on resistance to Fusarium disease spread. (A) Number of damaged spikelets following point inoculation with either F. graminearum or deoxynivalenol (DON) of the ears of wheat cv. Maris Huntsman NILs allelic at the Rht-B1 loci at 14 dpi. Black bars represent F. graminearum inoculated ears. *** Significant difference (P <0.001) from rht-tall. Grey bars represent DON treated ears. ††, ††† Significant difference (P <0.01 and P <0.001, respectively) from rht-tall. Bars ±1 SEM. (B, C) Typical symptom spread and contained phenotype in rht-tall and Rht-B1c lines following point inoculation with F. graminearum and DON, respectively. Injected spikelet is arrowed. (D) Mean cell death lesion area (cm2) following F. graminearum inoculation of the leaves of wheat and barley lines 6 dpi. **, *** Significant difference (P <0.01 and P <0.001) from the corresponding wild type. Bars ±1 SEM. (E) Representative lesions on leaves of wild-type and mutant plants corresponding to labels in (D) stained with trypan blue to detect cell death. The central circles show inoculation points.

Influence of DELLA on lesion development induced by F. graminearum on leaves of wheat and barley

Wound inoculation of leaves with F. graminearum also bypasses defence against initial infection, and thus disease development can be used to assess resistance to fungal spread independently of resistance to initial infection. Following wound inoculation of leaves, the zone of cell death about the inoculation point at 6 dpi was significantly greater (P=0.006) in Maris Huntsman wild type than the Rht-B1c NIL (Fig. 5D, E). Similarly, the zone was significantly greater (P <0.001) in Himalaya wild type than the Sln1d line (Fig. 5D, E). Cell death was not observed beyond the point of inoculation in wheat or barley following wounding alone (data not shown).

Interaction between DELLA and deoxynivalenol induced lesion development

Production of DON by F. graminearum is required for disease spread in wheat heads (Bai et al., 2002). To determine whether DELLA accumulating lines are more resistant to DON, bleaching symptoms induced by this mycotoxin were assessed following point inoculation with DON. In the wild-type Maris Huntsman line, bleaching symptoms spread an average of 4.3 spikelets from the point of inoculation at 14 dpi (Fig. 5A, C), whereas in the Rht-B1b line, symptom spread was significantly less (P <0.01) than in the wild-type line, with an average of 3.1 spikelets exhibiting symptoms at 14 dpi. Most strikingly, following injection of the Rht-B1c line, symptoms were restricted to the inoculated spikelet (Fig. 5A, C). Overall, these symptoms closely resembled those appearing following point inoculation with a DON-producing isolate of F. graminearum (Fig. 5A, B).

Influence of DELLA on deoxynivalenol-induced inhibition of root elongation of wheat and barley

DON has been demonstrated to inhibit root growth (Eudes et al., 2000). To assess the effect of DELLA on root growth in the presence of DON, treated and untreated roots of Maris Huntsman NILs (rht-tall, Rht-B1b, and Rht-B1c) and Himalaya WT and Sln1d were measured. DON-induced root inhibition was significantly less (P <0.001) for Rht-B1c than for the wild type (rht-tall) or Rht-B1b lines of Maris Huntsman (Table 4). The mean growth of DON-treated roots, relative to untreated roots across experiments was 56.4% for Rht-B1c, 40.0% for Rht-B1b, and 37.7% for the rht-tall line of Maris Huntsman. Similarly, the effect of DON on root growth of Himalaya WT and Sln1d also differed significantly (P <0.001; Table 1). The mean growth of DON-treated roots, relative to untreated roots across experiments was 44.4% for Sln1d, and 36.8% for the Himalaya wild-type line.

Table 4.

Root growth inhibition assay of rht-tall, Rht-B1b, and Rht-B1c near-isogenic lines of Maris Huntsman and Himalaya WT and Sln1d in the presence of deoxynivalenol

| Cultivar | Genotype | % Growth inhibition relative to untreated control | P-value comparison with wild-type |

| Maris Huntsman | rht-tall | 62.4 | |

| Rht-B1b | 60.0 | 0.39 | |

| Rht-B1c | 43.6 | <0.001 | |

| Himalaya | WT | 63.2 | |

| Sln1d | 55.6 | <0.001 |

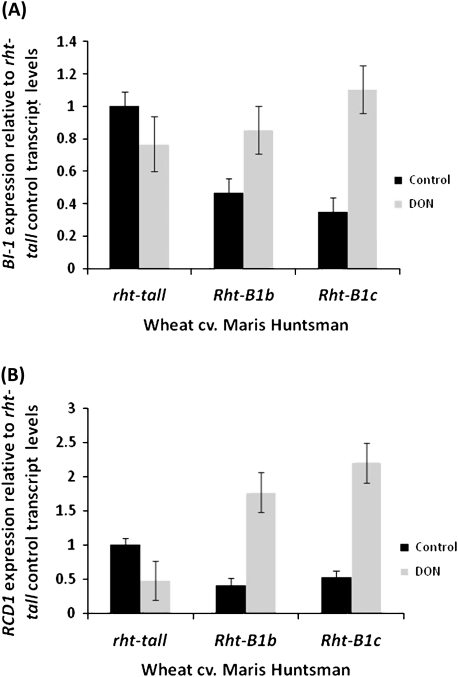

Influence of DELLA on deoxynivalenol-induced expression of negative cell death regulators

Deoxynivalenol has been demonstrated to induce H2O2 production and to promote host cell death (Desmond et al., 2008). To gain an insight into the mechanism of DELLA-conferred tolerance to DON, the expression of two candidate negative regulators of cell death, BAX INHIBITOR-1 (BI-1) and RADICAL INDUCED CELL DEATH 1 (RCD1), was quantified in rht-tall, Rht-B1b, and Rht-B1c Maris Huntsman NILs following exposure to DON (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

The effect of deoxynivalenol on the expression of genes involved in the negative regulation of cell death. BAX INHIBITOR-1 (A) and RADICAL INDUCED CELL DEATH 1 (B) expression was measured in the root tissue of wheat cv. Maris Huntsman NILs allelic at the Rht-B1 locus treated with water (control) or deoxynivalenol (DON). Target gene expression was normalized to 18S expression. Bars ±1 SEM.

Expression of BI-1 differed between the untreated rht-tall, Rht-B1b, and Rht-B1c NILs: expression was significantly lower in the Rht-B1b and Rht-B1c lines than in the rht-tall line (P=0.01 and P=0.003, respectively) while expression levels were similar for all three lines following treatment with DON (Fig. 6A). Treatment with DON did not significantly alter expression of BI-1 in the rht-tall line. By contrast, treatment with DON resulted in a significant increase in expression of BI-1 in both the Rht-B1b (P=0.048) and Rht-B1c (P=0.001) lines.

Expression of RCD1 in the untreated roots also differed between the rht-tall, Rht-B1b, and Rht-B1c NILs. Although it was not significantly different, expression was lower in the Rht-B1b and Rht-B1c lines than in the untreated rht-tall line (Fig. 6B). No significant difference was observed in the rht-tall lines following DON treatment while, by contrast, DON treatment resulted in a significant increase in expression of RCD1 in both the Rht-B1b (P=0.001) and Rht-B1c (P <0.001) lines. Following DON treatment the expression of RCD1 was significantly (P <0.001) greater in both the Rht-B1b or Rht-B1c lines than in the rht-tall line.

Discussion

The reduced GA sensitivity of the DELLA Rht-B1b and Rht-D1b semi-dwarfing alleles in wheat were central to enhanced crop yields achieved as part of the Green Revolution (Hedden, 2003). However, research using Arabidopsis has indicated that DELLA may have pleiotropic effects, including an altered response to pathogens. Using DELLA mutants in Arabidopsis, Navarro et al. (2008) showed that DELLAs promote susceptibility to biotrophs and resistance to necrotrophs. Such findings are potentially significant in agriculture but information relating to potential pleiotropic effects in monocotyledonous species is currently lacking.

In the current study, the role of DELLA proteins in response to pathogens was investigated in two important monocotyledonous crop species. In contrast to Arabidopsis, H. vulgare (barley) is a diploid species which contains a single DELLA-encoding gene. Both GoF and LoF mutants are available in barley arising from point mutations enabling us to observe the effect of Sln1 without the gene redundancy present in Arabidopsis and wheat. Using these mutants, it was demonstrated that DELLA confers a resistance trade-off to a range of fungal pathogens with differing trophic lifestyles that are responsible for some economically important diseases of cereals. T. aestivum (bread wheat) is a polyploid species originating from the hybridization of three diploid progenitors and as such contains three DELLA-encoding genes. Using GoF mutants in polyploids, a correlation between dwarfing severity and influence on resistance was also demonstrated. In addition, the effect of polyploidy has been assessed, observing how disease resistance is influenced by DELLA alleles conferring semi-dwarf and severe-dwarf phenotypes, functioning in the presence of background wild-type homoeologous DELLA-encoding genes. The results reported in this study using diverse DELLA mutants in two cereal species indicates that the effect on disease resistance to pathogens with differing lifestyles is due to pleiotropy rather than linkage. Thus our findings support those previously reported in dicot species (Navarro et al., 2008) that suggested a pleiotropic role of DELLA in disease resistance.

Biotrophic pathogens derive their nutrients from living host cells. All obligate biotrophic pathogens possess specialist feeding structures, known as haustoria, which penetrate the cell wall. Recognition of the invading pathogen results in an increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) production leading to the hypersensitive response (HR), a type of programmed cell death which deprives biotrophic pathogens of their food source. Studies in Arabidopsis have implicated DELLA proteins in processes leading to cell death. Achard et al. (2008) demonstrated that DELLAs delay ROS-induced cell death and Navarro et al. (2008) reported that DELLAs suppress the accumulation of salicylic acid (SA) and cell death in response to infection by Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato. In the present study, microscopic analysis of the host defence response in the barley–B. graminis (biotroph) interaction showed that the DELLA LoF line is hypersensitive to cell death resulting in complete resistance, whilst the frequency of hypersensitive cell death was reduced in the DELLA GoF line, resulting in a higher number of successful haustorial establishment events (Fig. 3). As in Arabidopsis DELLA accumulating mutants, the barley DELLA GoF line may exhibit a delay in ROS-induced cell death which, in turn, reduces the effectiveness of the HR thereby increasing susceptibility both to an obligate biotroph, B. graminis (Figs 1, 2) and to a hemibiotroph with a long biotrophic or endophytic phase, R. collo cygni (Table 2).

The height reduction associated with the Sln1d (GoF) allele in barley is similar to that associated with Rht-B1c and Rht-D1c alleles in wheat (c. 50% of the respective wild type). However, in contrast to the significantly enhanced susceptibility to B. graminis of the barley Sln1d line (Fig. 1), wheat lines carrying single mutant alleles, Rht-B1c or Rht-D1c did not exhibit an equivalent increase in susceptibility. The combination of dwarf and semi-dwarf mutant alleles (Rht-B1c+Rht-D1b) in a single line, however, did enhance susceptibility. In polyploid species like wheat, the presence of wild-type homoeologous copies of the Rht genes might buffer the negative effect of a single mutation on susceptibility to B. graminis. It is conceivable that DELLA accumulation must pass a threshold in order significantly to delay cell death induced by B. graminis and that this threshold is exceeded in Rht-B1c+Rht-D1b (dwarf+semi dwarf) NILs carrying mutations in two of their three Rht (DELLA) homoeologues but not in lines carrying a mutation in only a single homoeologue. Further investigation with other biotrophic pathogens is necessary to determine whether this phenomenon is specific to B. graminis or common to other biotrophs.

Hemibiotrophic pathogens exhibit an initial biotrophic phase before switching to a necrotrophic lifestyle. The barley pathogen, R. collo-cygni, is a hemibiotroph with a prolonged biotrophic phase during which time the fungus grows intercellularly, colonizing the spaces between the mesophyll cells (Sutton and Waller, 1988; Stabentheiner et al., 2009). The barley lines carrying the GoF or LoF DELLA mutations showed differential responses to R. collo-cygni with the GoF mutant being significantly more susceptible and the LoF mutant significantly more resistant than the wild type (Table 2). These results suggest that DELLA-mediated prevention of cell death benefits the initial biotrophic phase of R. collo-cygni infection and supports the current view that R. collo-cygni has a long biotrophic phase (Walters et al., 2008).

Necrotrophic pathogens derive their nutrients from dead host cells. These pathogens have evolved a number of strategies to kill host cells including the secretion of toxins, cell-wall-degrading enzymes, and eliciting ROS production. If, as reported, DELLA prevents ROS-induced cell death then it would be predicted that plants with increased DELLA accumulation would be more resistant to necrotrophs than their tall counterparts. O. acuformis is considered to be a typical necrotrophic pathogen while the closely related species O. yallundae exhibits a very short non-necrotrophic initial phase during the infection of wheat (Blein et al., 2009). Both species cause eyespot disease on the stem base of cereals and are considered a serious disease of winter wheat in northern Europe and north-west USA (Fitt, 1992). GoF mutations of DELLA in both wheat and barley resulted in significantly increased resistance to both Oculimacula species as might be anticipated given their necrotrophic lifestyles. Supportive of DELLA increasing resistance to necrotrophs, the barley LoF mutant exhibits enhanced susceptibility to eyespot caused by O. acuformis.

Interestingly, the effect on the GoF mutation in wheat was greater for O. acuformis than for O. yallundae. It is speculated that this reflects the different growth habits of the two species. Whilst O. acuformis exhibits an invasive growth habit, O. yallundae penetrates the coleoptile in a more ordered, intramural manner (Daniels et al., 1991), with no sign of host cell death (Blein et al., 2009). Once at the first leaf sheath the pathogen initiates the formation of an infection plaque from which hyphae grow and penetrate the first, then successive leaf sheaths facilitated by the secretion of cell-wall-degrading enzymes (Mbwaga et al., 1997). These observations suggest that O. yallundae may be considered to be a hemibiotroph with a very short initial phase of biotrophic growth before switching to a necrotrophic phase once the pathogen reaches the first leaf sheath (Blein et al., 2009) while O. acuformis exhibits the traits of a conventional necrotroph.

F. graminearum was originally considered to be entirely necrotrophic. However, evidence is accumulating to indicate that this may not always be the case. Analysis of the interaction at the cellular level shows that F. graminearum exhibits extracellular growth during the early stages of infection (Pritsch et al., 2000) and sub-cuticular growth reminiscent of O. yallundae (Rittenour and Harris, 2010). It appears that F. graminearum requires a transient biotrophic phase of establishment before switching to necrotrophic nutrition during the infection of wheat leading to FHB (Goswami and Kistler, 2004). This view is supported by studies on the interaction of FHB with the SA and JA signalling pathways. SA content and expression of the SA-inducible PR1 gene in Arabidopisis inoculated with F. graminearum showed that SA signalling is activated in the early stages of infection (Makandar et al., 2010). Furthermore, over-expression of a gene that regulates SA signalling (NPR1), in wheat and Arabidopsis, increases resistance to F. graminearum (Makandar et al., 2006). Methyl jasmonate (MJ), however, has dichotomous effects on the susceptibility of Arabidopsis to F. graminearum. The application of MJ during the early stages of infection enhanced disease severity, presumably due to JA attenuating SA signalling, whilst, when applied at later stages of infection, MJ reduced disease severity (Makandar et al., 2010).

Short wheat varieties tend to be more susceptible to FHB in the field than tall ones and it has been demonstrated that semi-dwarf lines carrying the Rht-B1b allele are more susceptible to initial infection than those carrying the wild-type allele (Srinivasachary et al., 2009). In the present study, it has been demonstrated that both Rht-B1b and Rht-B1c NILs exhibit increased Type 1 susceptibility (initial infection) relative to the wild type, and that this is associated with the severity of the DELLA effect on plant height. By contrast, following point inoculation, Rht-B1b and Rht-B1c NILs exhibited increased resistance to disease spread relative to the wild type and this also correlates with the DELLA effect on plant height. DELLA GoF dwarf lines of both wheat and barley also showed enhanced resistance to cell death following wound-inoculation of leaves with F. graminearum. Overall, these results indicate that, whilst DELLA accumulating lines are more susceptible to the initial establishment phase they are more resistant to the later colonization phase. It is proposed that these contrasting differential susceptibilities reflect the different trophic modes of growth employed by F. graminearum and support the evidence that F. graminearum exhibits an initial biotrophic phase during FHB infection prior to entering a longer necrotrophic phase.

The trichothecene mycotoxin DON functions as a virulence factor for F. graminearum during colonization (Bai et al., 2002). The up-regulation of trichothecene biosynthetic genes and subsequent accumulation of DON in head tissues have been observed 48 hpi (Boddu et al., 2006). This is thought to signal the switch from biotrophic to necrotrophic growth. DON has been shown to induce H2O2 production in the host, promoting cell death (Desmond et al., 2008). In addition, in vitro experiments have demonstrated that H2O2 induces DON production by the fungus (Ponts et al., 2006) leading to a cycle that ultimately favours necrotrophy. Plant lines with enhanced capabilities of alleviating oxidative stress would be anticipated to exhibit increased resistance to F. graminearum and DON. This view is supported by a number of studies. For example, increases in the activity of the antioxidant enzymes superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT) positively correlated with FHB resistance in a set of wheat varieties inoculated with DON-producing isolates (Chen et al., 1997). Similarly, the Arabidopsis RADICAL-INDUCED CELL DEATH 1 (AtRCD1) wheat homologue, referred to as CLONE EIGHTY ONE, that is thought to regulate oxidative stress responses negatively (Overmyer et al., 2000) accumulated in higher amounts in DON-tolerant lines compared with susceptible lines (Walter et al., 2008).

In the present study, it was found that GoF DELLA lines were more resistant both to colonization by F. graminearum and to DON-induced cell death than their tall counterparts, probably due, at least in part, to a reduced propensity of these plants to initiate or undergo cell death. DELLA proteins have been shown to up-regulate genes involved in the ROS scavenging system such as CSD1/2 which encode SOD in response to stress (Achard et al., 2008). It was observed that expression of RCD1 (CEO) and BI-1, that has a putative role in the regulation of cell death (Huckelhoven, 2004), is greater in the roots of wheat DELLA GoF lines than in the wild type following treatment with DON (Fig. 6). Interestingly a trade-off in resistance to pathogens with opposing lifestyles has been observed in barley lines over-expressing HvBI-1. These plants exhibit enhanced susceptibility to Blumeria and enhanced resistance to Fusarium that is associated with their decreased propensity to undergo cell death (Babaeizad et al., 2009). Trade-off between susceptibility to biotrophs and resistance to necrotrophs, and vice versa, has also been demonstrated in barley lines lacking MLO function, which exhibit increased resistance to Blumeria whilst enhancing susceptibility to necrotrophic pathogens (Jarosch et al., 1999; Kumar et al., 2001).

Our data demonstrate that DELLA plays a central and dichotomous role in resistance to necrotrophic and biotrophic pathogens in cereal monocot species in a manner similar to that observed in Arabidopsis (Navarro et al. 2008). Single DELLA GoF mutants of both barley (diploid) and wheat (hexaploid) exhibited enhanced resistance to necrotrophic pathogens (F. graminearum, and Oculimacula species). However, while the barley GoF mutant exhibited significantly enhanced susceptibility to a biotrophic pathogen (Blumeria f. sp.), increased susceptibility in wheat was only observed when two of the three DELLA homoeologues were mutated. These findings indicate that, while the semi-dwarfing alleles deployed in present-day wheat cultivars provide increased tolerance to necrotrophic pathogens, due to the polyploid nature of wheat, they confer only a negligible effect on susceptibility to Blumeria (and possibly other obligate biotrophs). Appreciation of the role of DELLA in responses to biotic stress in cereals is important in plant breeding where the pleiotropic effect on disease resistance of Rht alleles used to achieve appropriate plant stature will have to be balanced through enhancing disease resistance as suggested for FHB by Miedaner and Voss (2008).

Acknowledgments

This work has been funded by the UK Biotechnology and Biological Science Research Council (BBSRC). We thank JIC horticultural and field services for assistance with trials. We also thank Dr Peter Chandler, CSIRO, Australia, and Dr John Flintham, JIC, Norwich for providing seed and Dr Marc Lemmens, IFA-Tulln, Austria for providing DON.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- DON

deoxynivalinol

- ET

ethylene

- FHB

Fusarium head blight

- GoF

gain of function

- GA

gibberellin

- GS

growth stage

- JA

jasmonic acid

- LoF

loss of function

- NILs

near-isogenic lines

- qRT-PCR

quantitative real-time PCR

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SA

salicylic acid

References

- Abramoff MD, Magelhaes PJ, Ram SJ. Image processing with Image J. Biophoton International. 2004;11:36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Achard P, Gong F, Cheminant S, Alioua M, Hedden P, Genschik P. The cold-inducible CBF1 factor-dependent signaling pathway modulates the accumulation of the growth-repressing DELLA proteins via its effect on gibberellin metabolism. The Plant Cell. 2008;20:2117–2129. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.058941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babaeizad V, Imani J, Kogel KH, Eichmann R, Huckelhoven R. Over-expression of the cell death regulator BAX inhibitor-1 in barley confers reduced or enhanced susceptibility to distinct fungal pathogens. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2009;118:455–463. doi: 10.1007/s00122-008-0912-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahat A, Gelernter I, Brown MB, Eyal Z. Factors affecting the vertical progression of septoria leaf blotch in short-statured wheats. Phytopathology. 1980;70:179–184. [Google Scholar]

- Bai GH, Desjardins AE, Plattner RD. Deoxynivalenol-nonproducing Fusarium graminearum causes initial infection, but does not cause disease spread in wheat spikes. Mycopathologia. 2002;153:91–98. doi: 10.1023/a:1014419323550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blein M, Levrel A, Lemoine J, Gautier V, Chevalier M, Barloy D. Oculimacula yallundae lifestyle revisited: relationships between the timing of eyespot symptom appearance, the development of the pathogen and the responses of infected partially resistant wheat plants. Plant Pathology. 2009;58:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Boddu J, Cho S, Kruger WM, Muehlbauer GJ. Transcriptome analysis of the barley-Fusarium graminearum interaction. Molecular Plant–Microbe Interactions. 2006;19:407–417. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-19-0407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd LA, Smith PH, Brown JKM. Molecular and cellular expression of quantitative resistance in barley to powdery mildew. Physiological and Molecular Plant Pathology. 1994a;45:47–58. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd LA, Smith PH, Green RM, Brown JKM. The relationship between the expression of defense-related genes and mildew development in barley. Molecular Plant–Microbe Interactions. 1994b;7:401–410. [Google Scholar]

- Brown JKM, Wolfe MS. Structure and evolution of a population of Erysiphe graminis f. sp. hordei. Plant Pathology. 1990;39:376–390. [Google Scholar]

- Brown NA, Urban M, Van De Meene AML, Hammond-Kosack KE. The infection biology of Fusarium graminearum: defining the pathways of spikelet to spikelet colonisation in wheat ears. Fungal Biology. 2010;114:555–571. doi: 10.1016/j.funbio.2010.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler PM, Marion-Poll A, Ellis M, Gubler F. Mutants at the Slender1 locus of barley cv. Himalaya. Molecular and physiological characterization. Plant Physiology. 2002;129:181–190. doi: 10.1104/pp.010917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman NH, Burt C, Dong H, Nicholson P. The development of PCR-based markers for the selection of eyespot resistance genes Pch1 and Pch2. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2008;117:425–433. doi: 10.1007/s00122-008-0786-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Song Y, Xu Y, Nie L, Xu L. Comparison for activities of superoxide dismutase and catalase between scab-resistant and susceptible wheat varieties. Acta Phytopathologica Sinica. 1997;27:209–213. [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Steed A, Travella S, Keller B, Nicholson P. Fusarium graminearum exploits ethylene signalling to colonize dicotyledonous and monocotyledonous plants. New Phytologist. 2009;182:975–983. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels A, Lucas JA, Peberdy JF. Morphology and ultrastructure of W-pathotype and R-pathotype of Pseudocercosporella herpotrichoides on wheat seedlings. Mycological Research. 1991;95:385–397. [Google Scholar]

- Desmond OJ, Manners JM, Stephens AE, MaClean DJ, Schenk PM, Gardiner DM, Munn AL, Kazan K. The Fusarium mycotoxin deoxynivalenol elicits hydrogen peroxide production, programmed cell death and defence responses in wheat. Molecular Plant Pathology. 2008;9:435–445. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2008.00475.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draeger R, Gosman N, Steed A, et al. Identification of QTLs for resistance to Fusarium head blight, DON accumulation and associated traits in the winter wheat variety Arina. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2007;115:617–625. doi: 10.1007/s00122-007-0592-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen L, Borum F, Jahoor A. Inheritance and localisation of resistance to Mycosphaerella graminicola causing Septoria tritici blotch and plant height in the wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) genome with DNA markers. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2003;107:515–527. doi: 10.1007/s00122-003-1276-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eudes F, Comeau A, Rioux S, Collin J. Phytotoxicity of eight mycotoxins associated with fusarium in wheat head blight. Canadian Journal of Plant Pathology–Revue Canadienne De Phytopathologie. 2000;22:286–292. [Google Scholar]

- Fitt BDL. Eyespot of cereals. In: Singh US, Mukhopadhyay AN, Kumar J, Chaube HS, editors. Plant dseases of international importance, Vol. 1. Diseases of cereals and culses. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall Inc; 1992. pp. 337–355. [Google Scholar]

- Flintham JE, Borner A, Worland AJ, Gale MD. Optimizing wheat grain yield: effects of Rht (gibberellin-insensitive) dwarfing genes. Journal of Agricultural Science. 1997;128:11–25. [Google Scholar]

- Gervais L, Dedryver F, Morlais JY, Bodusseau V, Negre S, Bilous M, Groos C, Trottet M. Mapping of quantitative trait loci for field resistance to Fusarium head blight in an European winter wheat. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2003;106:961–970. doi: 10.1007/s00122-002-1160-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glazebrook J. Contrasting mechanisms of defense against biotrophic and necrotrophic pathogens. Annual Review of Phytopathology. 2005;43:205–227. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.43.040204.135923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosman N, Bayles R, Jennings P, Kirby J, Nicholson P. Evaluation and characterization of resistance to fusarium head blight caused by Fusarium culmorum in UK winter wheat cultivars. Plant Pathology. 2007;56:264–276. [Google Scholar]

- Goswami RS, Kistler HC. Heading for disaster: Fusarium graminearum on cereal crops. Molecular Plant Pathology. 2004;5:515–525. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2004.00252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedden P. The genes of the Green Revolution. Trends in Genetics. 2003;19:5–9. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(02)00009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huckelhoven R. BAX Inhibitor-1, an ancient cell death suppressor in animals and plants with prokaryotic relatives. Apoptosis. 2004;9:299–307. doi: 10.1023/b:appt.0000025806.71000.1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarosch B, Kogel KH, Schaffrath U. The ambivalence of the barley Mlo locus: mutations conferring resistance against powdery mildew (Blumeria graminis f. sp. hordei) enhance susceptibility to the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe grisea. Molecular Plant–Microbe Interactions. 1999;12:508–514. [Google Scholar]

- Klahr A, Zimmermann G, Wenzel G, Mohler V. Effects of environment, disease progress, plant height and heading date on the detection of QTLs for resistance to Fusarium head blight in an European winter wheat cross. Euphytica. 2007;154:17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar J, Huckelhoven R, Beckhove U, Nagarajan S, Kogel KH. A compromised Mlo pathway affects the response of barley to the necrotrophic fungus Bipolaris sorokiniana (Teleomorph: Cochliobolus sativus) and its toxins. Phytopathology. 2001;91:127–133. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.2001.91.2.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemmens M, Scholz U, Berthiller F, et al. The ability to detoxify the mycotoxin deoxynivalenol colocalizes with a major quantitative trait locus for fusarium head blight resistance in wheat. Molecular Plant–Microbe Interactions. 2005;18:1318–1324. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-18-1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis DH. Concepts in fungal nutrition and origin of biotrophy. Biological Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. 1973;48:261–278. [Google Scholar]

- Makandar R, Essig JS, Schapaugh MA, Trick HN, Shah J. Genetically engineered resistance to Fusarium head blight in wheat by expression of Arabidopsis NPR1. Molecular Plant–Microbe Interactions. 2006;19:123–129. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-19-0123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makandar R, Nalam V, Chaturvedi R, Jeannotte R, Sparks AA, Shah J. Involvement of salicylate and jasmonate signaling pathways in Arabidopsis interaction with Fusarium graminearum. Molecular Plant–Microbe Interactions. 2010;23:861–870. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-23-7-0861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makepeace JC, Havis ND, Burke JI, Oxley SJP, Brown JKM. A method of inoculating barley seedlings with Ramularia collo-cygni. Plant Pathology. 2008;57:991–999. [Google Scholar]

- Mbwaga AM, Menke G, Grossmann F. Investigations on the activity of cell wall-degrading enzymes in young wheat plants after infection with Pseudocercosporella herpotrichoides (Fron) Deighton. Journal of Phytopathology–Phytopathologische Zeitschrift. 1997;145:123–130. [Google Scholar]

- Miedaner T, Moldovan A, Ittu M. Comparison of spray and point inoculation to assess resistance to fusarium head blight in a multienvironment wheat trial. Phytopathology. 2003;93:1068–1072. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.2003.93.9.1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miedaner T, Voss HH. Effect of dwarfing Rht genes on Fusarium head blight resistance in two sets of near-isogenic lines of wheat and check cultivars. Crop Science. 2008;48:2115–2122. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro L, Bari R, Achard P, Lison P, Nemri A, Harberd NP, Jones JDG. DELLAs control plant immune responses by modulating the balance and salicylic acid signaling. Current Biology. 2008;18:650–655. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.03.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overmyer K, Tuominen H, Kettunen R, Betz C, Langebartels C, Sandermann H, Kangasjarvi J. Ozone-sensitive Arabidopsis rcd1 mutant reveals opposite roles for ethylene and jasmonate signaling pathways in regulating superoxide-dependent cell death. The Plant Cell. 2000;12:1849–1862. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.10.1849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne RW, Murray DA, Harding SA, Baird DB, Soutar DM. GenStat for Windows (12th Edition). Introduction. Hemel Hempstead: VSN International; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Peng JR, Carol P, Richards DE, King KE, Cowling RJ, Murphy GP, Harberd NP. The Arabidopsis GAI gene defines a signaling pathway that negatively regulates gibberellin responses. Genes and Development. 1997;11:3194–3205. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.23.3194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng JR, Richards DE, Hartley NM, et al. 'Green revolution' genes encode mutant gibberellin response modulators. Nature. 1999;400:256–261. doi: 10.1038/22307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perfect SE, Green JR. Infection structures of biotrophic and hemibiotrophic fungal plant pathogens. Molecular Plant Pathology. 2001;2:101–108. doi: 10.1046/j.1364-3703.2001.00055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Research. 2001 doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. 29, e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponts N, Pinson-Gadais L, Verdal-Bonnin MN, Barreau C, Richard-Forget F. Accumulation of deoxynivalenol and its 15-acetylated form is significantly modulated by oxidative stress in liquid cultures of Fusarium graminearum. FEMS Microbiology Letters. 2006;258:102–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritsch C, Muehlbauer GJ, Bushnell WR, Somers DA, Vance CP. Fungal development and induction of defense response genes during early infection of wheat spikes by Fusarium graminearum. Molecular Plant–Microbe Interactions. 2000;13:159–169. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2000.13.2.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rittenour WR, Harris SD. An in vitro method for the analysis of infection-related morphogenesis in Fusarium graminearum. Molecular Plant Pathology. 2010;11:361–369. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2010.00609.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder HW, Christensen JJ. Factors affecting resistance of wheat to scab caused by Gibberella zeae. Phytopathology. 1963;53:831–838. [Google Scholar]

- Scott PR. Effect of temperature on eyespot (Cercosporella herpotrichoides) in wheat seedlings. Annals of Applied Biology. 1971;68:169–175. [Google Scholar]

- Scott PR, Benedikz PW, Cox CJ. A genetic-study of the relationship between height, time of ear emergence and resistance to Septoria nodorum in wheat. Plant Pathology. 1982;31:45–60. [Google Scholar]

- Scott PR, Benedikz PW, Jones HG, Ford MA. Some effects of canopy structure and microclimate on infection of tall and short wheats by Septoria nodorum. Plant Pathology. 1985;34:578–593. [Google Scholar]

- Silverstone AL, Ciampaglio CN, Sun TP. The Arabidopsis RGA gene encodes a transcriptional regulator repressing the gibberellin signal transduction pathway. The Plant Cell. 1998;10:155–169. doi: 10.1105/tpc.10.2.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasachary Gosman N, Steed A, Hollins TW, Bayles R, Jennings P, Nicholson P. Semi-dwarfing Rht-B1 and Rht-D1 loci of wheat differ significantly in their influence on resistance to Fusarium head blight. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2009;118:695–702. doi: 10.1007/s00122-008-0930-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stabentheiner E, Minihofer T, Huss H. Infection of barley by Ramularia collo-cygni: scanning electron microscopic investigations. Mycopathologia. 2009;168:135–143. doi: 10.1007/s11046-009-9206-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton BC, Waller JM. Taxonomy of Ophiocladium hordei, causing leaf lesions on triticale and other graminaeae. Transactions of the British Mycological Society. 1988;90:55–61. [Google Scholar]

- Ueguchi-Tanaka M, Ashikari M, Nakajima M, et al. GIBBERELLIN INSENSITIVE DWARF1 encodes a soluble receptor for gibberellin. Nature. 2005;437:693–698. doi: 10.1038/nature04028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueguchi-Tanaka M, Nakajima M, Katoh E, et al. Molecular interactions of a soluble gibberellin receptor, GID1, with a rice DELLA protein, SLR1, and gibberellin. The Plant Cell. 2007;19:2140–2155. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.043729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanbeuningen LT, Kohli MM. Deviation from the regression of infection on heading and height as a measure of resistance to Septoria tritici blotch in wheat. Plant Disease. 1990;74:488–493. [Google Scholar]

- Walter S, Brennan JM, Arunachalam C, et al. Components of the gene network associated with genotype-dependent response of wheat to the Fusarium mycotoxin deoxynivalenol. Functional and Integrative Genomics. 2008;8:421–427. doi: 10.1007/s10142-008-0089-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters DR, Havis ND, Oxley SJP. Ramularia collo-cygni: the biology of an emerging pathogen of barley. FEMS Microbiology Letters. 2008;279:1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00986.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen CK, Chang C. Arabidopsis RGL1 encodes a negative regulator of gibberellin responses. The Plant Cell. 2002;14:87–100. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zadoks JC, Chang TT, Konzak CF. Decimal code for growth stages of cereals. Weed Research. 1974;14:415–421. [Google Scholar]