Abstract

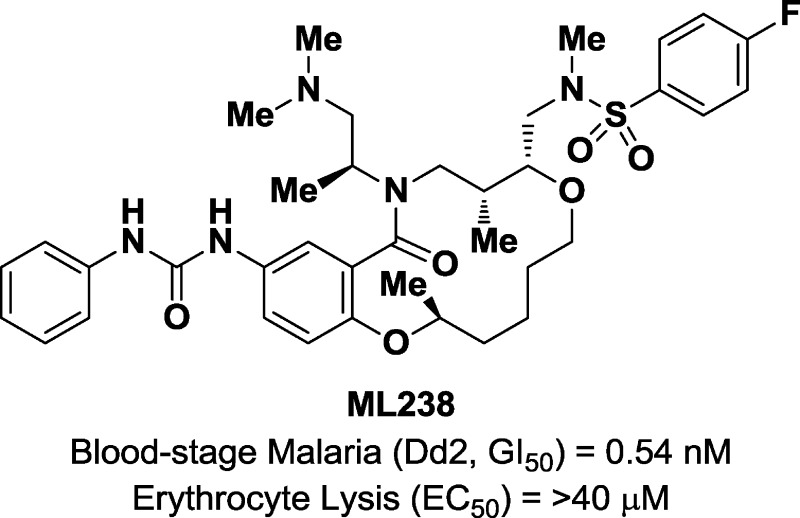

Here, we describe the discovery of a novel antimalarial agent using phenotypic screening of Plasmodium falciparum asexual blood-stage parasites. Screening a novel compound collection created using diversity-oriented synthesis (DOS) led to the initial hit. Structure–activity relationships guided the synthesis of compounds having improved potency and water solubility, yielding a subnanomolar inhibitor of parasite asexual blood-stage growth. Optimized compound 27 has an excellent off-target activity profile in erythrocyte lysis and HepG2 assays and is stable in human plasma. This compound is available via the molecular libraries probe production centers network (MLPCN) and is designated ML238.

Keywords: diversity-oriented synthesis, malaria, macrocycle, high-throughput screening, phenotypic screen, infectious disease, molecular libraries probe production centers, stereochemical structure−activity relationships

Malaria afflicts approximately 225 million people and leads to ∼780 000 deaths per year.1,2 The apicomplexan Plasmodium parasite responsible for this condition is contracted via Anopheles mosquito bites and lives a part of its life cycle within this vector.3 Endemic areas are limited to the tropics, where continuous mosquito breeding is possible. Several species of Plasmodium can infect mammalian hosts, and Plasmodium falciparum is the most prevalent cause of fatal outcomes in malaria patients.4

Chemotherapy over a period of decades has likely contributed to the high degree of genetic diversity within these parasites.5 The emergence of resistance to antimalarial drugs has led to poor treatment outcomes.6 The current best practice is a combination therapy with the artemisinin family of antimalarial agents.7 In addition to drug resistance, malaria is prevalent in underdeveloped nations with poor infrastructures, high population densities, and insufficient health care funding. These factors have combined to present a challenging clinical environment.8 Combination therapies have been used to mitigate the rate of resistance in several diseases.9 As such, new small molecules with novel mechanism(s) of action have the greatest potential to enable a successful path to the treatment of drug-resistant malarial infections.10,11

Diversity-oriented synthesis (DOS)12−14 yields small molecules having diverse stereochemistries and skeletons. Short, modular synthetic pathways, for example, using the build/couple/pair (B/C/P) strategy, facilitate downstream efforts using medicinal chemistry. These novel compounds effectively complement traditional screening collections.15−21 Our recent efforts22 have focused on incorporating both structure–activity relationships (SAR) and stereochemical structure–activity relationships (SSAR) into the library design, thereby enabling quick prioritization of hit clusters from primary screens. Coupling this initial SAR with the ability to synthesize analogues rapidly using modular synthetic pathways provides an efficient process to pursue hits identified using high-throughput screening (HTS). These principles were highlighted recently by an aldol-based B/C/P strategy, resulting in compounds having medium-sized and macrocyclic rings derived from a common linear intermediate.23,24 This report describes an HTS that yielded novel compounds having antimalarial activity and subsequent medicinal chemistry that yielded a promising and novel subnanomolar inhibitor of the major etiologic agent of severe malaria, P. falciparum.

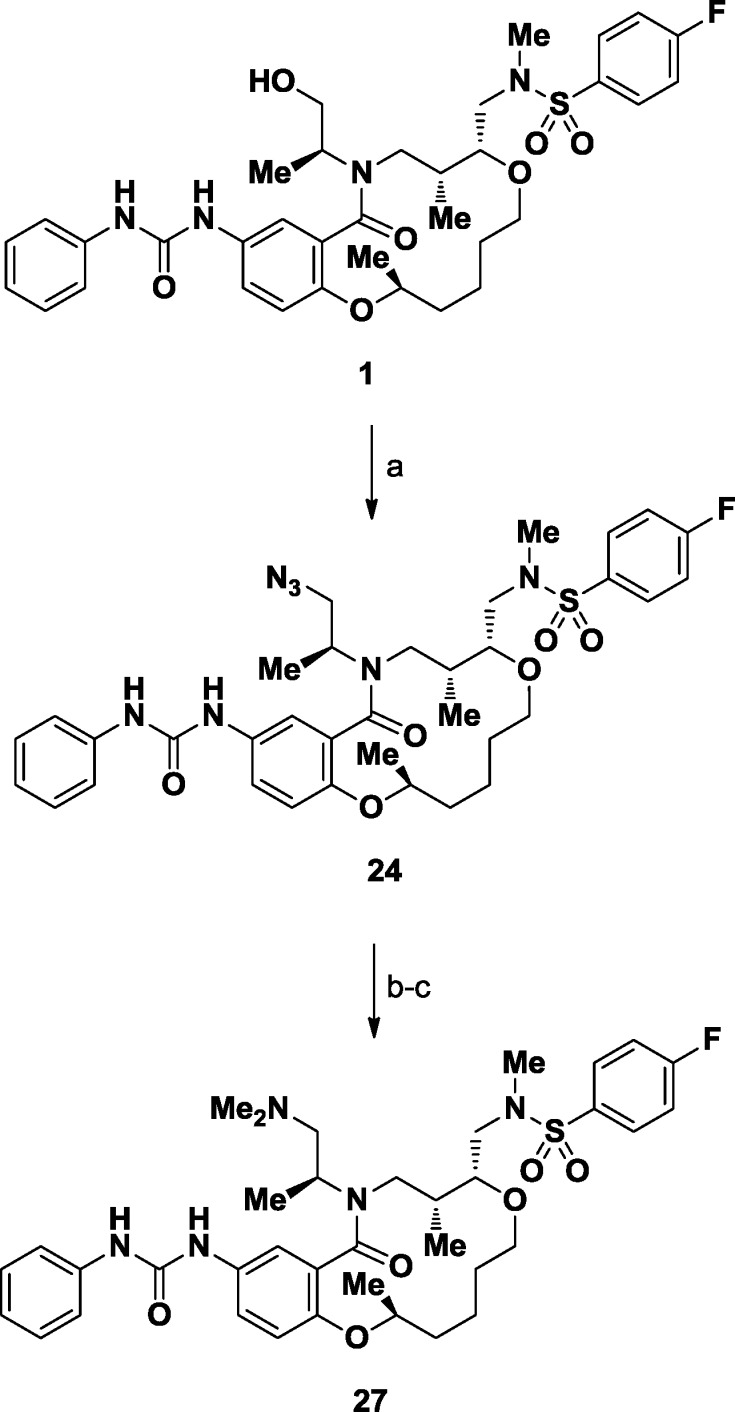

We initiated the search for novel antimalarial agents via HTS of an 8000-membered DOS 'informer' collection in a phenotypic blood-stage malaria assay.25 This representative set of compounds was computationally selected for maximum diversity representing all libraries in our collection while maintaining the full complement of all possible stereoisomers of each compound. HTS was conducted in triplicate at a 5 μM compound concentration using a growth inhibition assay (72 h, DAPI) with multidrug-resistant Dd2 P. falciparum parasites (Figure 1). A total of 560 compounds showed greater than 90% growth inhibition, and titration at a four concentrations further narrowed the list to 26 candidates (>50% inhibition at 280 nM). Of these, 20 compounds were from the 'ring-closing metathesis' (RCM) library, and this scaffold was selected for further studies.26

Figure 1.

Graphical depiction of the HTS triage.

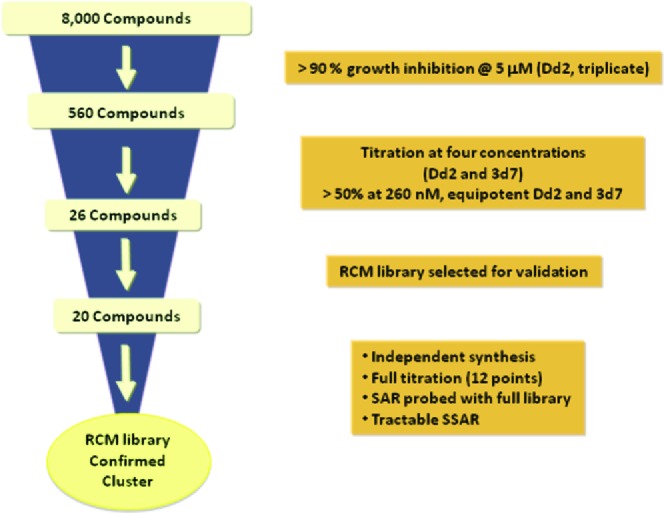

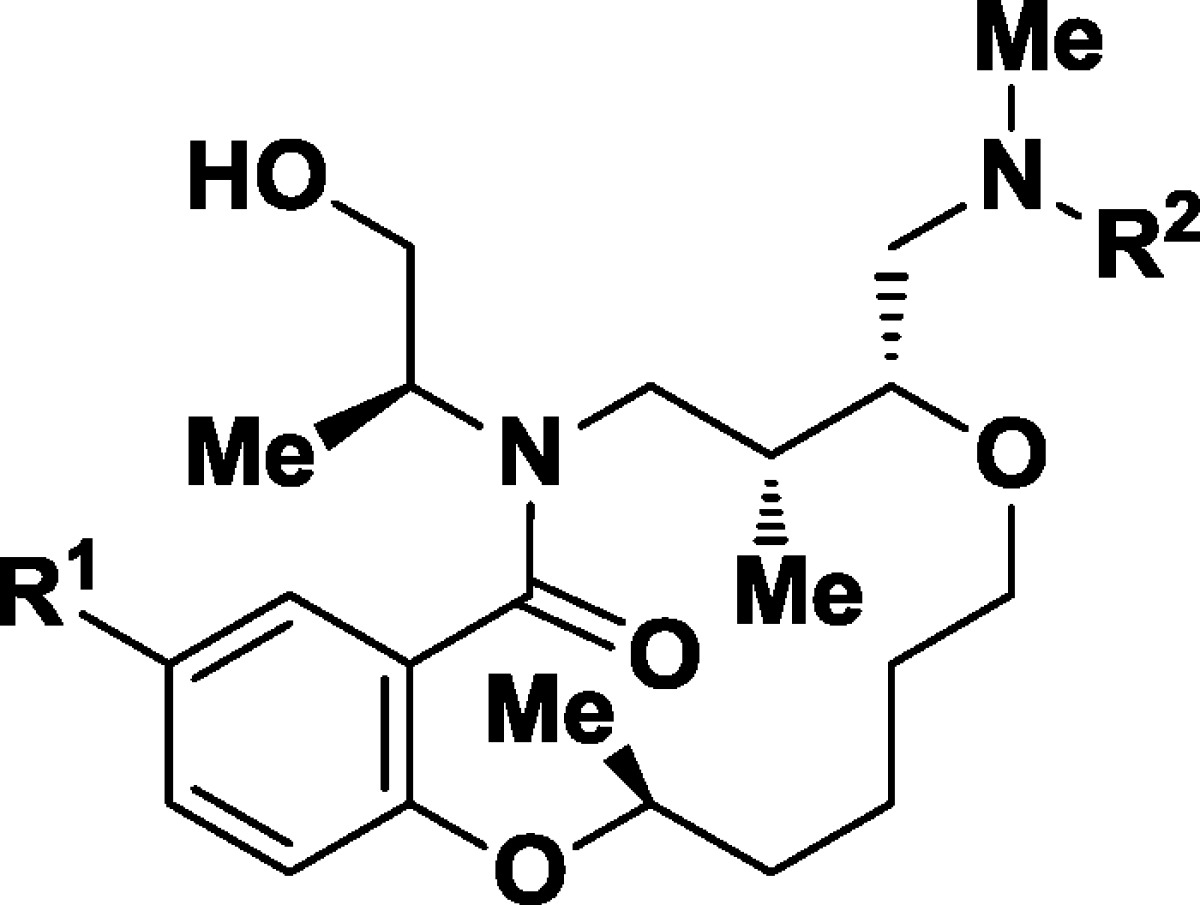

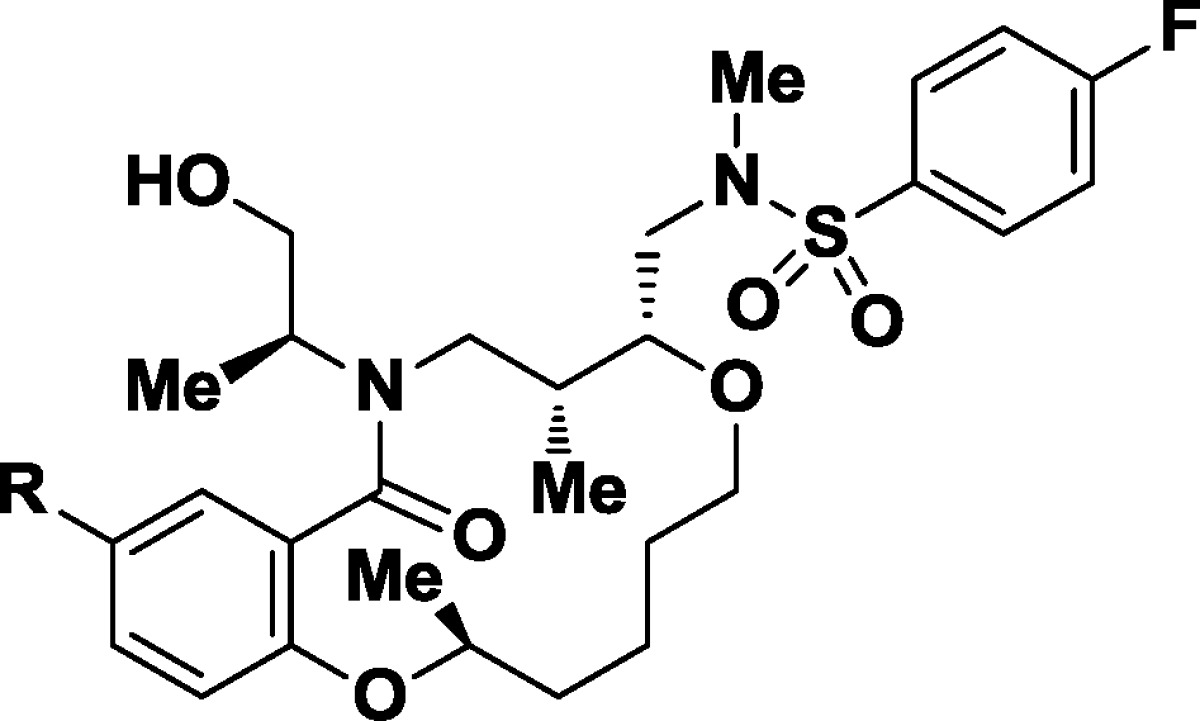

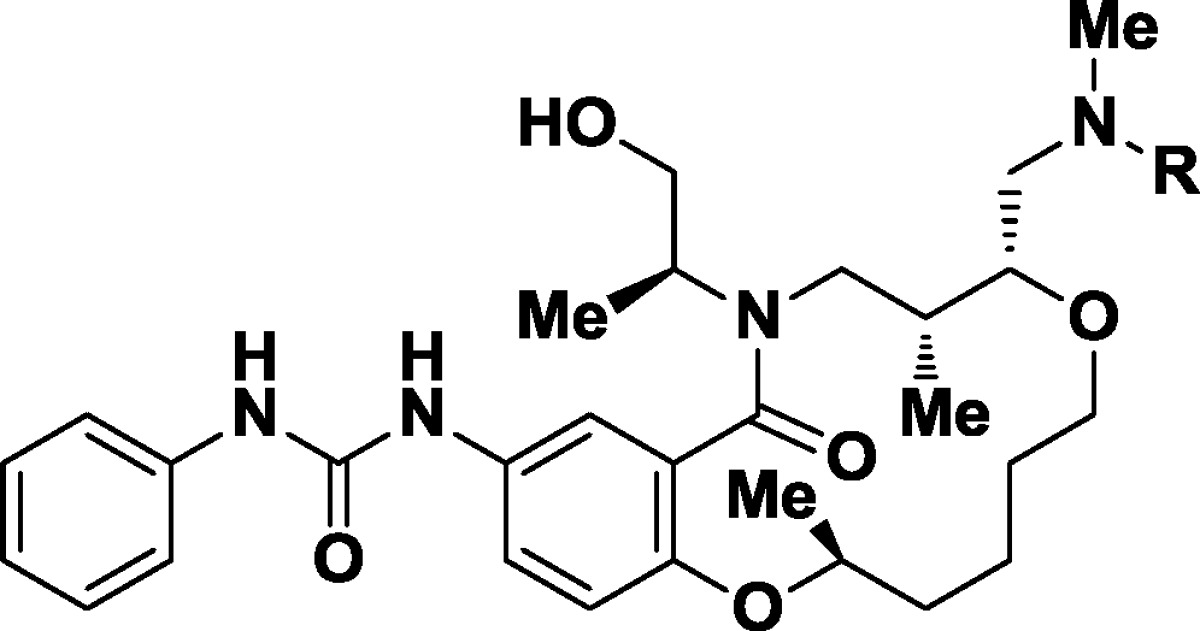

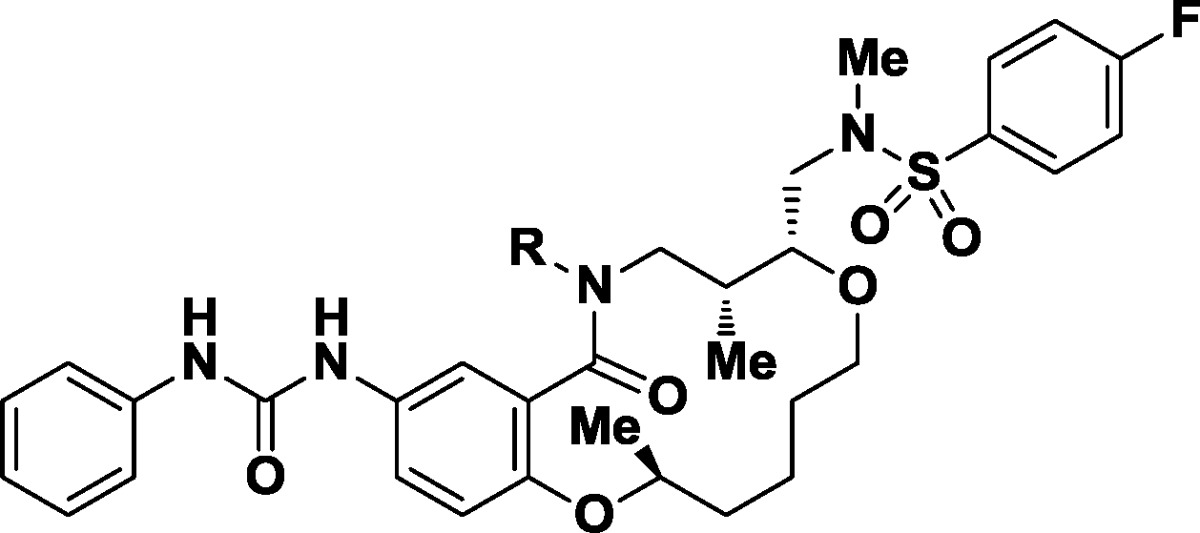

The most active hit (compound 1, Figure 2) was independently synthesized and iteratively titrated in a 12-point assay to confirm a potency (GI50) of 120 nM against Dd2 intraerythrocytic parasites (GI50 values were obtained with Dd2 parasites unless otherwise specified). This lead has a similar potency in the drug-sensitive 3d7 parasite strain and does not cause hemolysis of erythrocytes at up to 40 μM concentration; unfortunately, it is largely insoluble in aqueous solution (<0.5 μM in water). The stereochemical SAR (SSAR) analysis of all 16 possible isomers of compound 1 demonstrates that interesting biological activity is predominantly located in two stereoisomeric compounds that are epimeric outside the macrocyclic ring (C2, Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Structure of lead compound 1, potency in two strains of blood-stage malaria parasites, and the SSAR of the hit.

In the first round of analogue testing, we searched the Broad Institute chemical compound collection for analogues of hit 1 that had the same SRRS configuration (C2C5C6C12) and retained one of the two (phenyl urea or 4-fluorophenyl sulfonamide) side chain diversity elements. This exercise resulted in more than 50 available analogues. The results of selected titrations are reported in Table 1. The first five structures show changes to the amine side chain. Alternatively substituted and unsubstituted sulfonamides 2 and 3 showed similar potency to the lead (GI50 = 160 and 350 nM, respectively), while the corresponding phenyl amide 4 (GI50 = 2600 nM) and benzyl amine 5 (GI50 = 1100 nM) demonstrated a loss in potency.

Table 1. SARs Derived from the Broad Compound Collection.

Alteration of the urea substituent from phenyl (1, L/D = 120 nM) to isopropyl (6, GI50 = 400 nM) or 2,4-dimethylisoxazolyl (7, GI50 = 240 nM) afforded compounds with somewhat diminished potency. Formal truncation of the urea to the dimethylaniline 8 (GI50 = >5000 nM) led to an inactive substrate, while the corresponding phenyl-sulfonamide 9 (GI50 = 2400 nM) also provided a less biologically interesting substrate. The presence of both reasonable SAR via the presence of close structural analogues in the compound collection combined with promising SSAR prompted additional investigation into this lead.

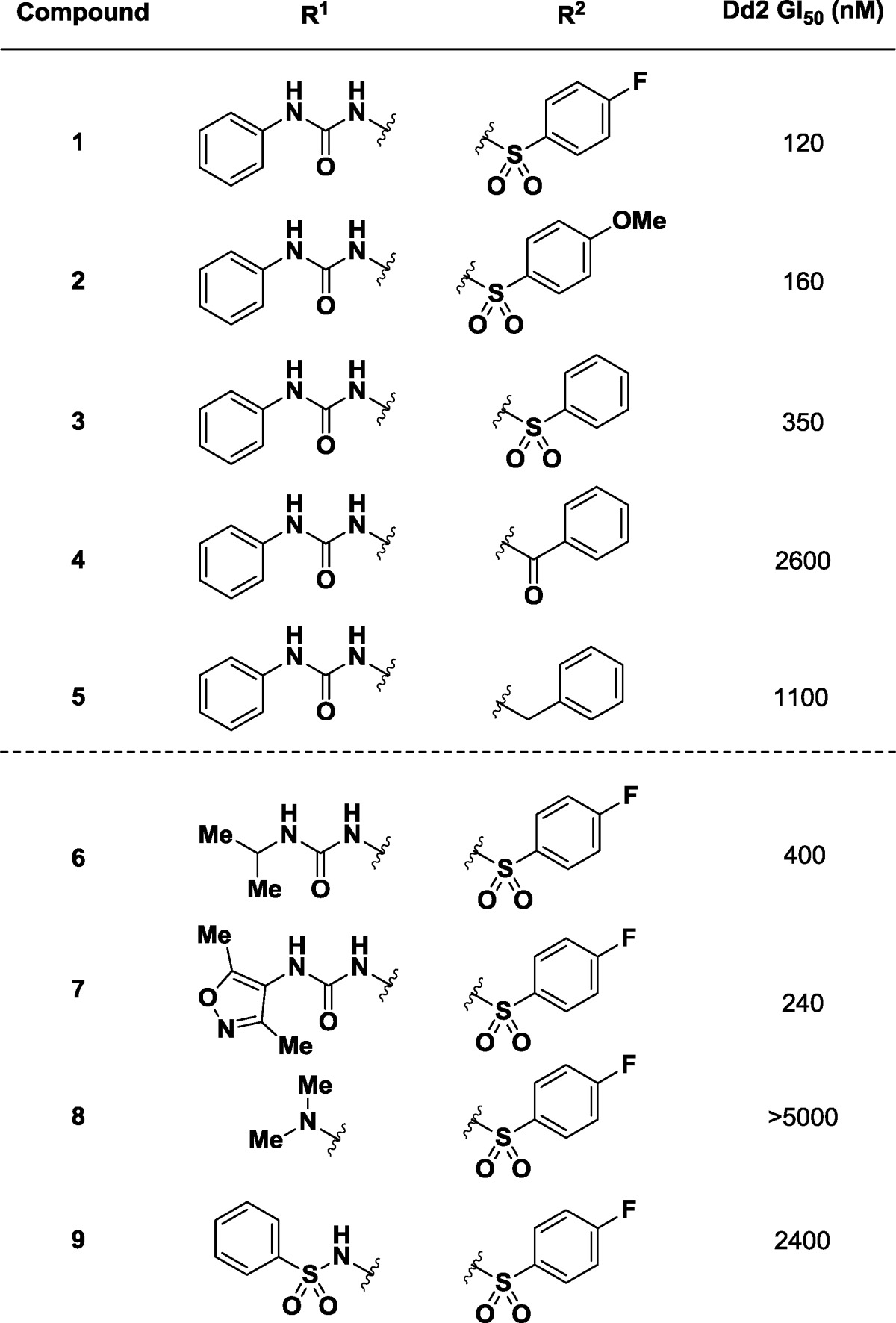

Independent preparation of interesting compounds and the synthesis of additional derivatives closely followed the strategy originally reported by Marcaurelle et al.24 These syntheses were performed in the solution phase. Protected intermediate 10 was converted into the requisite derivatives via iterative capping and deprotection steps (Figure 3). When the aniline group required masking, a 9-fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl (Fmoc) group was used. Details of the synthetic steps used to prepare these compounds can be found in the Supporting Information.

Figure 3.

Preparation of derivatives in the solution phase.

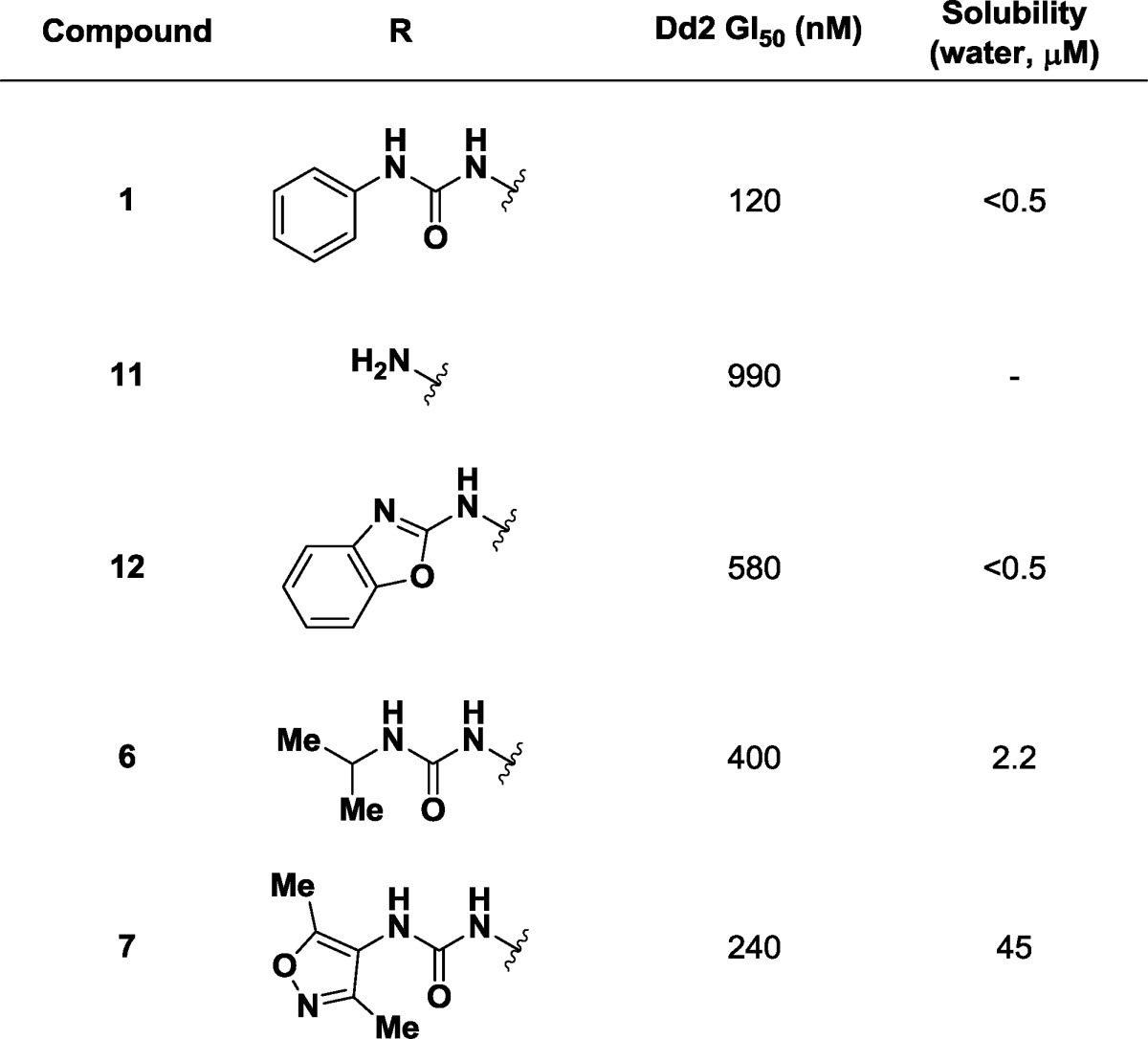

Our preliminary studies of the SAR of this novel lead revolved around monitoring potency in the growth inhibition assay while improving aqueous solubility by the addition of polar functional groups and attempting to remove hydrophobic bulk. We first directed our attention to the N,N′-diaryl urea (Table 2). Formal truncation of the urea group provides the corresponding aniline 11 (GI50 = 990 nM). Aniline 11, heterocyclic aminobenzoxazole 12 (GI50 = 580 nM), and the isopropyl urea 6 (GI50 = 400 nM) led to modest decreases in potency. We followed on the observation that the isopropyl urea 6 showed a modest increase in water solubility (water solubility =2.2 μM) by independent preparation of the heterocyclic and substituted 4-amino-3,5-dimethylisoxazolyl urea 7. This afforded a soluble derivative (water solubility = 45 μM) with some loss of potency (GI50 = 240 nM).

Table 2. Initial SARs of the Aryl Substituent.

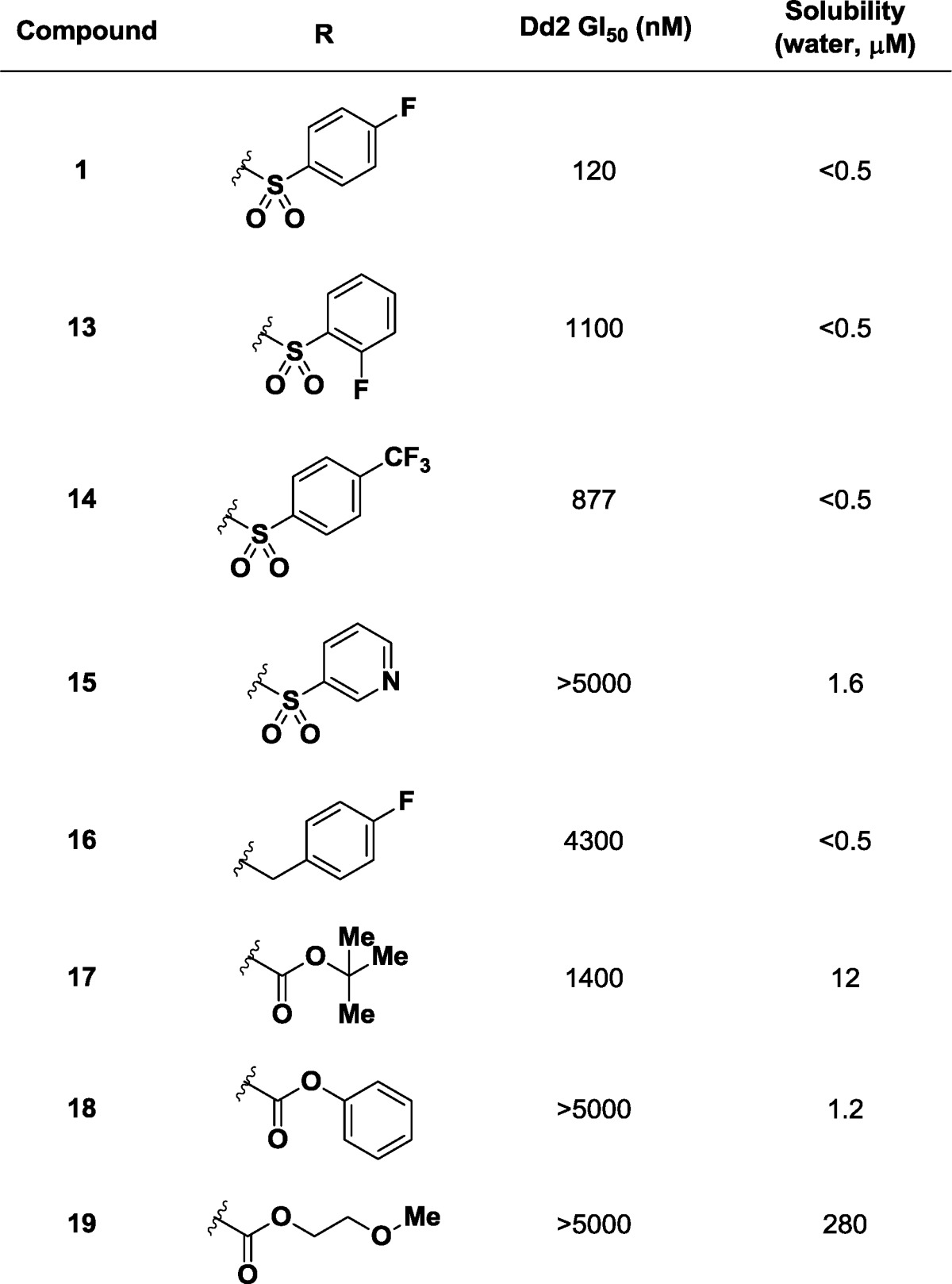

We next optimized the amine side chain for potency and solubility (Table 3). The regioisomeric 2-fluorophenylsulfonamide 13 has lower potency (GI50 = 1100 nM) when contrasted with the parent, and the 4-trifluoromethyl derivative 14 showed no improvement (GI50 = 880 nM). Hetereocycles such as 3-pyridylsulfonamide 15 were not tolerated (GI50 > 5000 nM), and benzylic amine 16 also showed a lack of potency in the primary phenotypic assay (GI50 = 4300 nM). Carbamate derivatives such as tert-butyl (17), phenyl (18), and methoxyethoxy (19) showed improvements in solubility but lost biological activity (all GI50 > 1400 nM).

Table 3. Initial SARs at the Amine Substitutent.

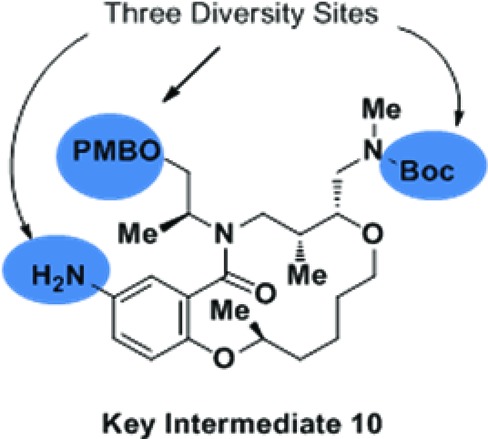

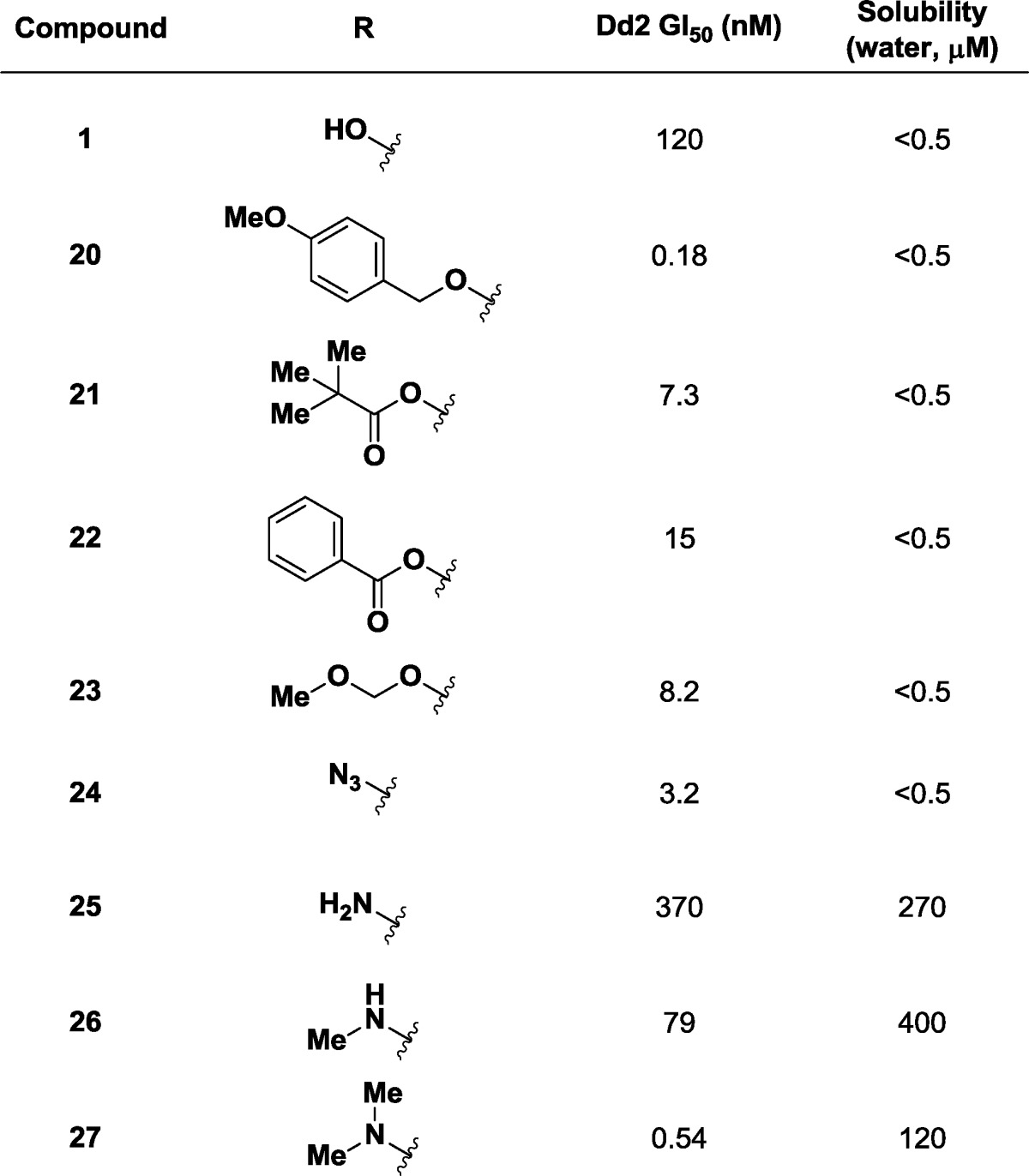

Exploration of alternate substituents of the amide group began serendipitously with the submission of protected derivatives to the growth inhibition assay (Table 4). The para-methoxybenzyl (PMB) ether 20 showed subnanomolar potency (GI50 = 0.18 nM). To confirm this result, other less lipophilic groups were appended to the alcohol. Pivalate (21, GI50 = 7.3 nM), benzoyl (22, GI50 = 15 nM), and methoxymethyl (23, GI50 = 8.2 nM) showed similar but somewhat diminished improvements in potency. Unfortunately, none of these compounds were soluble in water.

Table 4. Initial SARs at the Amide Substitutent.

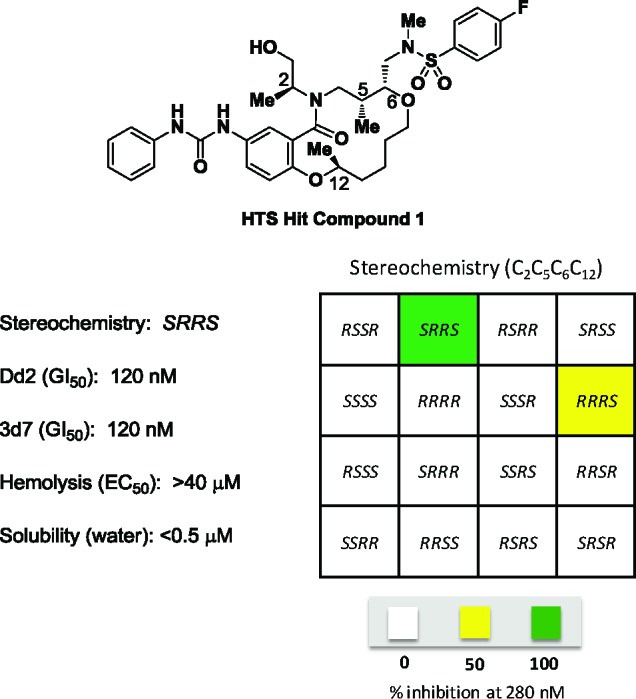

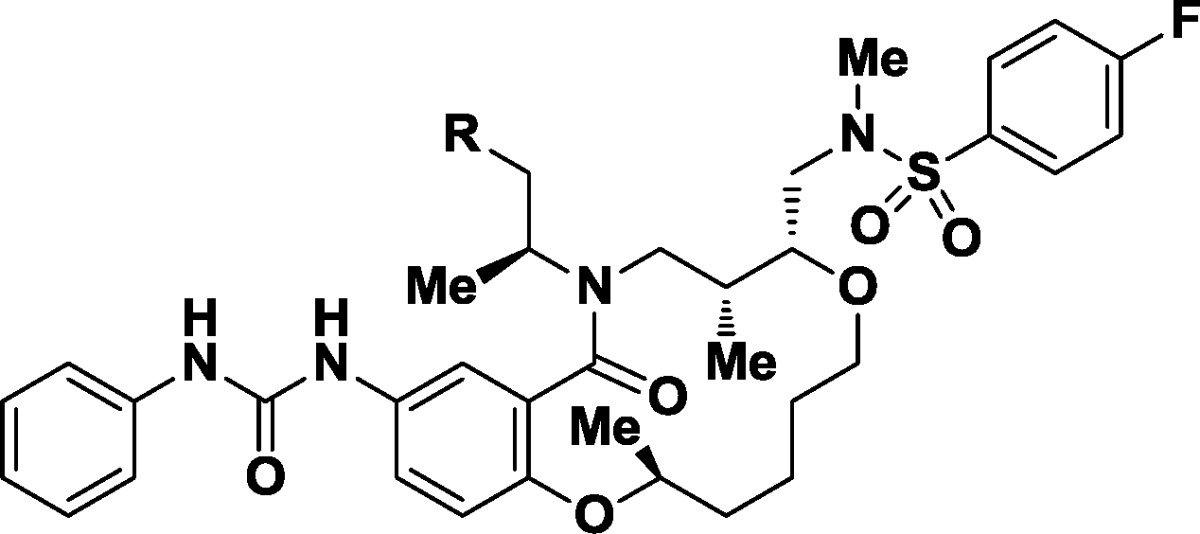

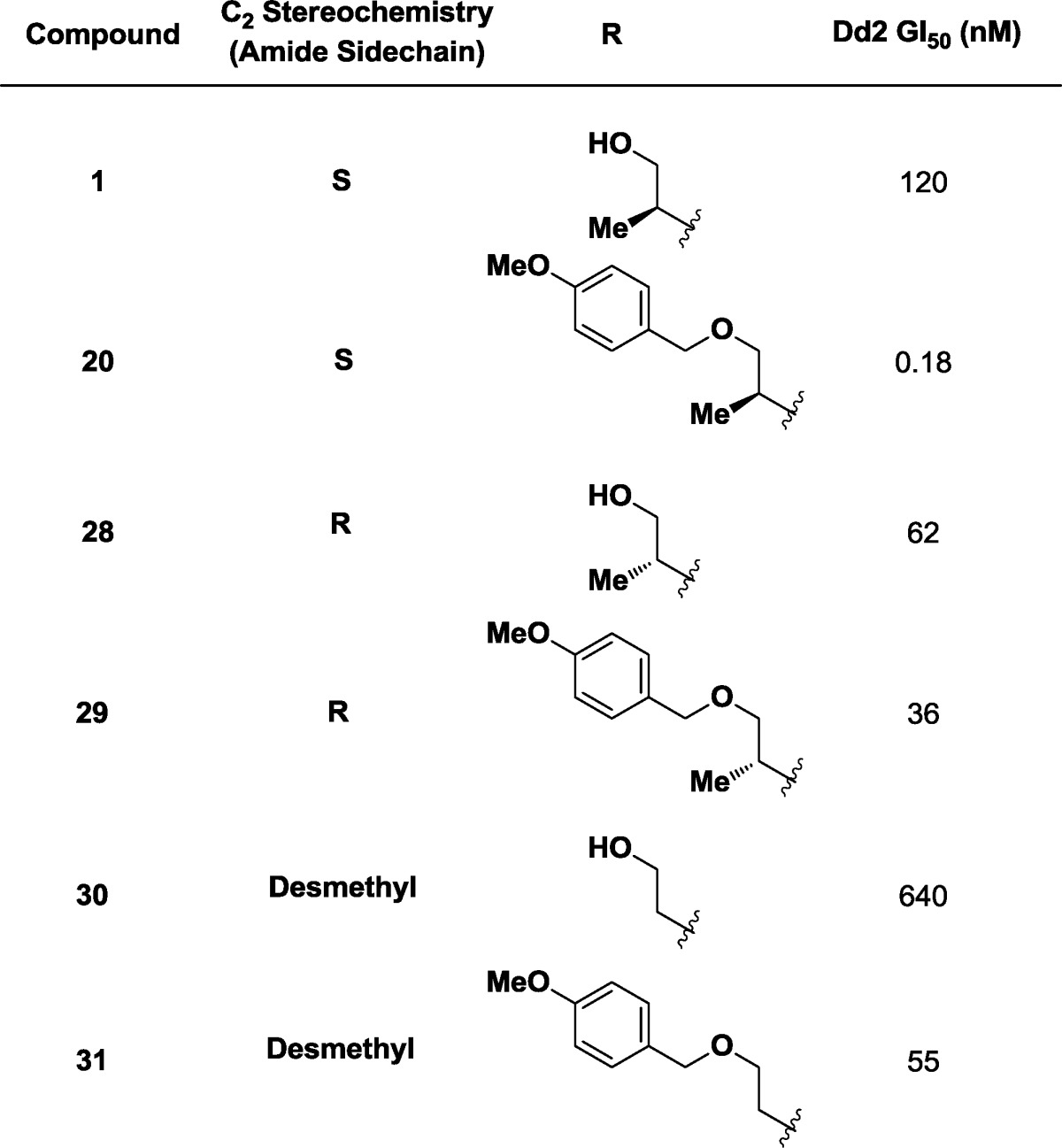

Displacement of the sterically hindered hydroxyl group within 1 with azide under Mitsunobu conditions afforded both a potent derivative (24, GI50 = 3.2 nM) and access to nitrogen-based functional groups expected to improve water solubility (Scheme1). Reduction provided soluble primary amine 25 (GI50 = 370 nM, water solubility = 268 μM). The corresponding monomethylamine 26 showed no improvements over its parent (GI50 = 79 nM, water solubility = 401 μM), while dimethylamino derivative 27 demonstrated both subnanomolar potency (GI50 = 0.54 nM) and solubility in water (water solubility = 120 μM).

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Probe 27 from Initial Lead 1.

Reagents and conditions: (a) DPPA, DBU, THF, 87%. (b) PPh3, H2O, THF, 76%. (c) CH2O, MgSO4, H2O, DCM; then NaBH(OAc)3, 87%.

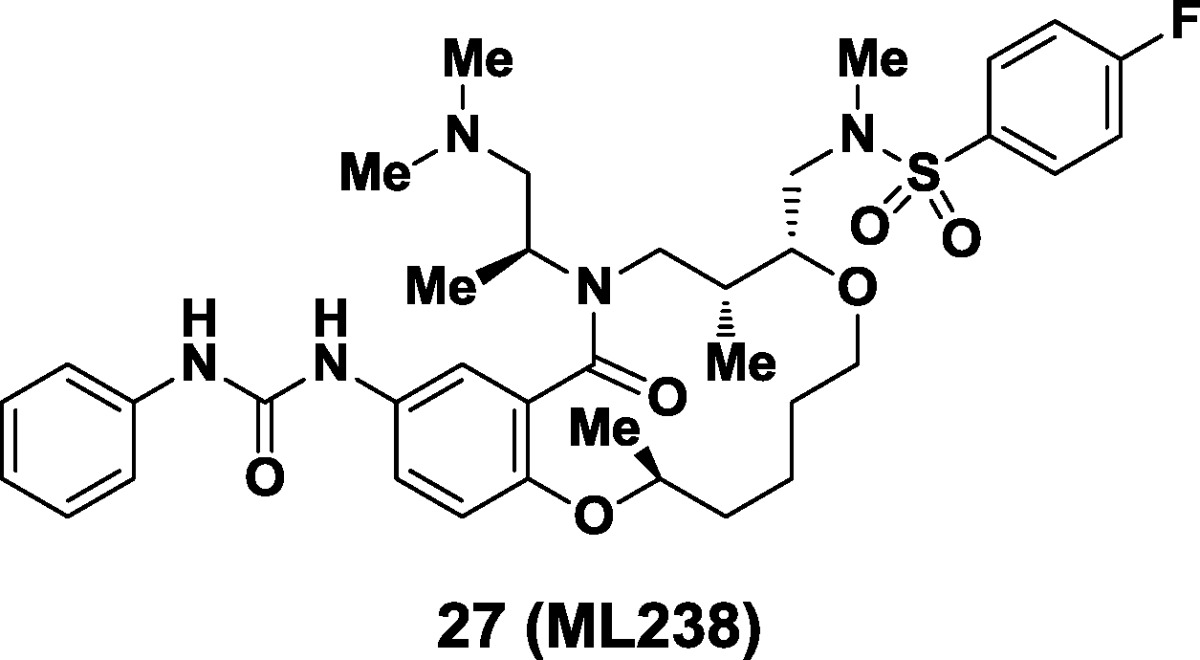

With this encouraging result in hand, we revisited the alternate stereochemical series on the C2 carbon located outside the macrocycle originally noted in the HTS screen (Table 5). Independent synthesis and titration of our original HTS hits showed that the two epimeric alcohols 1 and 28 had similar potency (GI50 = 120 and 62 nM, respectively), while desmethyl ethanol derivative 30 lost some activity (GI50 = 630 nM). As previously noted, the addition of a PMB ether in the S-series resulted in a 3–4 log improvement in potency (20, GI50 = 0.18 nM, vida supra). When the same formal transformation was performed on the epimeric (R) diastereomer and desmethyl examples, no correspondingly large potency improvements were observed (29, GI50 = 36 nM; and 31, GI50 = 55 nM). Confident that we were operating on the optimal stereoisomer, we nominated 27 as the Molecular Libraries Probe Production Centers Network (MLPCN) probe (ML238) and submitted it for further testing.

Table 5. SSARs at the Amide Substitutent.

Compound 27 has subnanomolar activity in two P. falciparum strains, and inhibition of parasite growth is not time dependent (contrasting 48–96 h time points, Table 6). The compound is more potent than chloroquine or artesunate and is similar in potency to atovoquone (GI50 = 0.54 nM, all three known antimalarial agents were used as controls). This compound is soluble in water (120 μM), and nontoxic to both erythrocytes (>40 μM) and HepG2 cells (>30 μM). In the presence of human plasma, it is highly protein-bound (99%) and stable (98% remaining at 5 h).

Table 6. Profile of Malaria Probe 27 (ML238).

| assay | result |

|---|---|

| live/dead (Dd2, GI50, 72 h) | 0.54 nM |

| live/dead (3d7, GI50, 96 h) | 0.54 nM |

| live/dead (3d7, GI50, 48 h) | 3.6 nM |

| solubility (water) | 120 μM |

| erythrocyte lysis | >40 μM |

| HepG2 | >30 μM |

| plasma protein binding (human) | 99% |

| plasma stability (human, 5 h) | 98% |

Studies of the mechanism of action of this new class of antimalarial agent are underway.27 Secondary assays have confirmed that representative compounds from this chemical series are not inhibitors of dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH) enzymes (human and parasite enzymes >30 μM).28,29 This compound (27) is available via the MLPCN and is designated ML238.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Stephen Johnston and Mike Lewandowski of the Broad Institute for analytical chemistry support and Norman Lee of Boston University for high-resolution mass spectroscopy.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- B/C/P

build/couple/pair

- DBU

- 1,8-diazobicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene

- DCM

- dichloromethane

- DHODH

dihydroorotate dehydrogenase

- DAPI

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- DOS

diversity oriented synthesis

- DPPA

- diphenylphosphoryl azide

- FMOC

9-fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl

- HTS

high-throughput screening

- GI50

phenotypic assay GI50 values utilizing Dd2 parasites

- MLPCN

Molecular Libraries Probe Production Centers Network

- PMB

para-methoxybenzyl

- RCM

ring-closing metathesis

- SAR

structure–activity relationships

- SSAR

stereochemical structure–activity relationship

Supporting Information Available

Experimental procedures and characterization of new chemical entities. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through the contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

This work was funded by the NIH-MLPCN program (1 U54 HG005032-1 awarded to S.L.S. and 5 U54MH08468-1 awarded to C.P.A.) and the NIGMS-sponsored Center of Excellence in Chemical Methodology and Library Development (Broad Institute CMLD; P50 GM069721). Funding for EHE and DAF was provided in part by the NIH (R01 AI079709). Funding for specificity testing was provided by Genzyme.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- World Health Organization. World Malaria Report; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood B. M.; Fidock D. A.; Kyle D. E.; Kappe S. H.; Alonso P. L.; Collins F. H.; Duffy P. E. Malaria: Progress, perils, and prospects for eradication. J. Clin. Invest. 2008, 118, 1266–1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissbuch I.; Leiserowitz L. Interplay between malaria, crystalline hemozoin formation, and antimalarial drug action and design. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 4899–4914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekland E. H.; Fidock D. A. In vitro evaluations of antimalarial drugs and their relevance to clinical outcomes. Int. J. Parasitol. 2008, 38, 743–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wootton J. C.; Feng X.; Ferdig M. T.; Cooper R. A.; Mu J.; Baruch D. I.; Magill A. J.; Su X.-Z. Genetic diversity and chloroquineselective sweeps in Plasmodium falciparum. Nature 2002, 418, 320–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackinnon M. J.; Marsh K. The selection landscape of malaria parasites. Science 2010, 328, 866–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastman R. T.; Fidock D. A. Artemisinin-based combination therapies: A vital tool in efforts to eliminate malaria. Nature Rev. Microbiol. 2009, 7, 864–874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snow R. W.; Okiro E. A.; Gething P. W.; Atun R.; Hay S. I. Equity and adequacy of international donor assistance for global malaria control: An analysis of populations at risk and external funding commitments. Lancet 2010, 376, 1409–1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kar S.; Kar S. Control of malaria. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2010, 9, 511–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells T. N. C.; Alonso P. L.; Gutteridge W. E. New medicines to improve control and contribute to the eradication of malaria. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2009, 8, 879–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu T.; Nagle A. S.; Chatterjee A. K. Road towards new antimalarials—Overview of the strategies and their chemical progress. Curr. Med. Chem. 2011, 18, 853–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke M. D.; Schreiber S. L. A planning strategy for diversity-oriented synthesis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 46–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber S. L. Target-oriented and diversity-oriented organic synthesis in drug discovery. Science 2000, 287, 1964–1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen T. E.; Schreiber S. L. Towards the optimal screening collection: a synthesis strategy. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 48–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer R. A.; Wurst J. M.; Tan D. S. Expanding the range of 'druggable' targets with natural product-based libraries: An academic perspective. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2010, 14, 308–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goess B. C.; Hannoush R. N.; Chan L. K.; Kirchhausen T.; Shair M. D. Synthesis of a 10,000-membered library of molecules resembling carpanone and discovery of vesicular traffic inhibitors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 5391–5403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubel K.; Lessmann T.; Waldmann H. Chemical biology—Identification of small molecule modulators of cellular activity by natural product inspired synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 37, 1361–1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch M. A.; Schuffenhauer A.; Scheck M.; Wetzel S.; Casaulta M.; Odermatt A.; Ertl P.; Waldmann H. Charting biologically relevant chemical space: a structural classification of natural products (SCONP). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005, 102, 17272–17277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcaurelle L. A.; Johannes C.; Yohannes D.; Tillotson B. P.; Mann D. Diversity-oriented synthesis of a cytisine-inspired pyridone library leading to the discovery of novel inhibitors of Bcl-2. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19, 2500–2503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcaurelle L. A.; Johannes C. W. Application of natural product-inspired diversity-oriented synthesis to drug discovery. Prog. Drug Res. 2008, 66, 189–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelish H. E.; Westwood N. J.; Feng Y.; Kirchhausen T.; Shair M. D. Use of biomimetic diversity-oriented synthesis to discover galanthamine-like molecules with biological properties beyond those of the natural product. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 6740–6741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou D. H.-C.; Duvall J. R.; Gerard B.; Liu H.; Pandya B. A.; Suh B.-C.; Forbeck E. M.; Faloon P.; Wagner B.; Marcaurelle L. A. Synthesis of a novel suppressor of β-cell apoptosis via diversity-oriented synthesis. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 2, 698–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerard B.; Duvall J. R.; Lowe J. T.; Murillo T.; Wei J.; Akella L. B.; Marcaurelle L. A.. ACS Comb. Sci. 2011, in press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Marcaurelle L. A.; Comer E.; Dandapani S.; Duvall J. R.; Gerard B.; Kesavan S.; Lee M. D. t.; Liu H.; Lowe J. T.; Marie J. C.; Mulrooney C. A.; Pandya B. A.; Rowley A.; Ryba T. D.; Suh B. C.; Wei J.; Young D. W.; Akella L. B.; Ross N. T.; Zhang Y. L.; Fass D. M.; Reis S. A.; Zhao W. N.; Haggarty S. J.; Palmer M.; Foley M. A. An aldol-based build/couple/pair strategy for the synthesis of medium- and large-sized rings: Discovery of macrocyclic histone deacetylase inhibitors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 6962–16976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The assay was performed as described in this report:Baniecki M. L.; Wirth D. F.; Clardy J. High-throughput Plasmodium falciparum growth assay for malaria drug discovery. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007, 51, 716–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The 'RCM' library was the most abundant scaffold (20/26 confirmed by titration) identified in this screening effort. Leads generated from other libraries will be the subject of future reports.

- McNamara C.; Winzeler E. A. Target identification and validation of novel antimalarials. Future Microbiol. 2011, 6, 693–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dihydroorotate dehydrogenase is a contemporary target in the control of malaria:Coteron J. M.; Marco M.; Esquivias J.; Deng X.; White K. L.; White J.; Koltun M.; El Mazouni F.; Kokkonda S.; Katneni K.; Bhamidipati R.; Shackleford D. M.; Angulo- Barturen I.; Ferrer S. B.; Jimenez-Díaz M. B.; Gamo F.-J.; Goldsmith E. J.; Charman W. N.; Bathurst I.; Floyd D.; Matthews D.; Burrows J. N.; Rathod P. K.; Charman S. A.; Phillips M. A. Structure-guided lead optimization of triazolopyrimidine-ring substituents identifies potent plasmodium falciparum dihydroorotate dehydrogenase inhibitors with clinical candidate potential. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 5540–5561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booker M. L.; Bastos C. M.; Kramer M. L.; Barker R. H. Jr.; Skerlj R.; Sidhu A. B.; Deng X.; Celatka C.; Cortese J. F.; Guerrero Bravo J. E.; Crespo Llado D. N.; Serrano A. E.; Angulo-Barturen I.; Jimenez-Díaz M. B.; Viera S.; Garuti H.; Wittlin S.; Papastogiannidis P.; Lin J.-W.; Janse C. J.; Khan S. M.; Duraisingh M.; Coleman B.; Goldsmith E. J.; Phillips M. A.; Munoz B.; Wirth D. F.; Klinger J. D.; Wiegand R.; Sybertz E. Novel inhibitors of Plasmodium falciparum dihydroorotate dehydrogenase with anti-malarial activity in the mouse model. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 33054–33064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.