Abstract

Background

Despite rapid growth, Latino communities’ mental health needs are unmet by existing services and research. Barriers may vary by geographic locations but often include language, insurance coverage, immigration status, cultural beliefs, and lack of services.

Objectives

The aim of this research was development of a cross-sectional instrument to assess the mental health status, beliefs, and knowledge of resources among rural and urban Latinos residing in a mid-western state.

Methods

The purpose of this article is to describe the Community Based Participatory Research process of instrument development and lessons learned.

Results

A culturally relevant, 100-item bilingual survey instrument was developed by community and academic partners.

Conclusions

Community-based participatory research methods are salient for sensitive health topics and varied research objectives, including instrument development. In order to ensure cultural and social relevance of research, community participation is crucial at all stages of research including developing the research question and instrument.

Keywords: Community-based participatory research, community health partnerships, community health research, power sharing, process issues, health services access, mental health, rural population, urban population

INTRODUCTION

In Minnesota, the growth of the Latino population nearly tripled during 1990–2000, surpassing national demographic trends.1 Most Latinos in Minnesota are U.S-born with foreign-born Latinos representing just 27.9% of the state’s overall foreign-born population, compared to 53% for the nation overall.2 Since Census 2000, the state’s Latino population has increased from approximately 130,000 Hispanic residents to 195,138 individuals, according to the 2006 American Community Survey.3,4 Estimates of undocumented workers vary widely, from 18,000 to 85,000.2 Another study estimates 20,000–35,000 migrant farm workers, many Latino, travel to Minnesota each summer.5 Although Latinos now comprise 3.8% of the state’s population, Latinos represent 21.2% of Minnesota’s population living below the federal poverty level.2 This disparity is likely due, in part, to high participation in agricultural occupations which have a high proportion of low-wage workers. For example, in rural south central Minnesota, the largest employers of Latino workers are food processing and packaging firms; an estimated 33% of the employees are Latino.6 Although more than a quarter of the population lives in rural counties, the major concentration of the Latino population is within the Twin Cities metropolitan area.7 Similar to nationwide trends, nearly 40 percent of the Latino population is under age 20, compared to only 25 percent of the white, not Latino population.8

Despite rapid growth, Latino communities have health needs that are persistently overlooked or unmet by existing services and research. For example, the rate of uninsurance among Latinos nearly doubled between 2001 to 2004, with Latinos five times less likely to be insured compared to whites.9 The barriers specific to mental health care services may vary by geographic location but often include language, insurance coverage, immigration status, cultural beliefs, and lack of services.10–13 In general, Latino adolescents have higher rates of depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation and attempts than white adolescents.15–18 There is also evidence that Latino adults and youth face generational differences in mental health status and needs.14

The project described in this article is based on the need for local data on mental health issues in Minnesota’s Latino communities in order to plan effective and culturally-appropriate services. Community-based participatory research (CBPR) emerged as the most appropriate methodology to gather data on sensitive issues of mental health. As indicated in the literature, one aim of CBPR is to advance and integrate knowledge into interventions and social change to improve community health.19, 20 This project embodies the complexities and possibilities of CBPR by including rural and urban partners, and cross-disciplinary researchers.

Study Aim

The aim of this research was development of a cross-sectional instrument to assess the mental health status, beliefs, and knowledge of resources among rural and urban Latinos residing in a mid-western state. The purpose of this article is to describe the CBPR process of instrument development and to describe relevant experiences and lessons learned.

PARTNERSHIP DEVELOPMENT

A unique feature of CBPR is that it can be initiated by community, university, or mutually. In this study, all such scenarios occurred. The Rural-University element resulted from an existing University partnership with a rural Latino-led organization. The Urban-University partnership evolved from disseminating and discussing prior University-initiated research findings about Latino adolescent health.

The project partners include two schools within the University of Minnesota (Medicine and Nursing), Centro Campesino in rural Minnesota, and health and social service agencies in urban Minnesota including West Side Community Health Services, Neighborhood House, and Hispanic Advocacy and Empowerment through Research (HACER).

Rural-University Partnership

The rural element of this CBPR project was catalyzed by a unique invitation to the University of Minnesota from Latino leaders in rural South Central Minnesota. Through the University’s women’s health outreach program, collaboration began in 2005 with Centro Campesino, a grassroots Latino-led organization with a mission to improve the lives of migrant agricultural workers and rural Latinos. Building on the existing partnership, Centro Campesino requested faculty collaboration to conduct a community mental health assessment. This request was prompted by Centro Campesino’s promotoras, who identified mental health as an urgent and unmet health need. As stated by a promatora, “People say to us: ‘I’m not crazy or suicidal but I want to forget my problems. Where do I go? Who can help me?’” As a national leader among Latino advocacy organizations, Centro Campesino had a particular interest in developing a mental health survey meeting rigorous academic research standards.

Urban-University Partnership

In 2002, Dr. Garcia (School of Nursing) began collaborating with Latino-serving schools and churches in the Twin Cities to address health-related concerns for Latino youth. This led to a two-year descriptive research project in which recently immigrated Latino adolescents used photovoice to describe their perceptions of health, including mental health.21 Community partners participated in planning next-steps and considered how to apply findings to existing programs. Subsequent dialogues emphasized the need for future research to address mental health. Teachers and social workers anecdotally reinforced current literature that indicated the mental health problems experienced by Latino youth are significant and require attention.18, 22, 23

Community-university partnerships blossomed in 2005 into a Community Advisory Alliance to facilitate inter-agency communication and provide a platform for Latino parent and adolescent involvement in decision-making. Quarterly Alliance meetings informed the design and implementation of the mental health instrument and discussed other research-related topics.

Rural-Urban-University Partnership

Until early 2005, University faculty were independently maintaining the aforementioned partnerships in distinct rural and urban areas of Minnesota. A coincidental encounter resulted in discussions and the decision to create a single, shared instrument. For University partners, the benefit of collaboration was twofold: 1) Combining rural and urban data provides a more comprehensive snapshot of Latino mental health in Minnesota than is possible independently and 2) to build an interdisciplinary partnership within the University as a strategy to address health disparities.24

At in-person meetings in urban and rural locations, community partners led discussion on project goals and intended outcomes, including the decision to use a single instrument at all sites. Principles of partnership were defined jointly, emphasizing the importance of open communication, mutual respect, and shared ownership of data. Community and academic partners committed to shared ownership of the project, including access to data.

INSTRUMENT DEVELOPMENT

The process of developing and pilot testing this instrument could be compared to an intricate dance. The non-linear experience required extensive communication, active listening, and consideration of numerous preferences. Decision-making was shared among partners in a time-intensive process that resulted in a comprehensive instrument to meet partners’ diverse needs. University partners assisted in identifying existing instruments and examining current literature for knowledge gaps. An extensive search of the scientific literature demonstrated that there was no existing instrument available assessing the mental health status, beliefs, and knowledge of resources that was culturally and linguistically appropriate for Latino adults or adolescents.

Community partners provided culturally relevant guidance in critiquing instruments and consent forms, including word choice for specific items. For example, instrument questions with five-point Likert scale responses were shortened to three level responses based on community member recommendations. Attention was also given to using simple but accurate language on the consent forms, especially related to mandated reporting and potential risks of participation in the survey.

The rural and urban Latino communities had slightly different initial foci for the instrument. The urban community aimed to assess the knowledge of existing mental health resources whereas the rural community sought increased understanding of the mental health status of the community. This may be due partly to the dearth of culturally-specific mental health services in rural areas. Ultimately all partners agreed on the benefit of including both dimensions: resources for and prevalence of mental health behaviors.

The final instrument contained one hundred items assessing mental health-related knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors (see Appendix A). It included items from existing self-report instruments validated in Spanish to assess psychiatric symptoms, such as the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression25 and the Perceived Stress Scale26 as well as established instruments assessing drug abuse,27 domestic violence, 28 and coping. 29 We developed adult and youth versions of the instrument in English and Spanish. In total, there exist four versions; each language available to each age group. To ensure translation validity, individuals independent of the project back-translated the Spanish version into English.

The timeline for this project from initial conversations in the rural and urban settings to collaboration within the university to piloting the instrument was approximately two and a half years. Conversations early in 2005 led to initiating instrument development at the end of 2005. IRB approval was sought early in 2006 and the urban and rural setting began piloting the instrument by the summer of 2006. The piloting in both settings was complete by the fall of 2007. CBPR driven research inherently requires extensive time at each stage of the research process; instrument design, revision and piloting is no exception.

Extensive revision of the instrument was done through electronic communication between partners; though in-person meetings were also essential to ensure integrity of the partnership principles such as shared power. Much attention was given to accurate translation of words and phrases describing mental health. The final name of the instrument is “Emotional Health Survey: Knowledge, Attitudes and Behaviors” instead of “Mental Health Survey.” This was selected after collaboratively defining emotional health as the ‘health of your mind, your feelings, and your emotions. Emotional health can be felt physically such as when you laugh to express happiness or cry when you are sad’. We recognized that avoiding ‘mental health’ terminology in the title could minimize potential negative reaction; this was also consistent with holistic views of physical and mental health commonly held within Latino communities.

INSTRUMENT PILOT

Urban Pilot Process

Piloting of the instrument in the urban setting occurred in two distinct simultaneous projects. First, grant funding provided resources to offer modest participant incentives (10$ Target Gift Cards) for adolescents recruited from school settings and adults recruited from clinic settings. Participants had the choice of completing the survey themselves or with a study team member in interview format.

Second, concurrent with our project there was a community mapping survey taking place in the Latino/Spanish-speaking neighborhoods using door-to-door interviewer data collection methods. Neighborhood House, the agency implementing the survey, had a history of working with Dr. Garcia in collaborative projects. This history facilitated conversations that ensued in adding a shortened version of the instrument to their community mapping interview protocol. Negotiation and flexibility by University and Community partners resulted in acquiring randomly collected community-level data. In retrospect, the result was a mixed blessing. Additional instruments were completed but because they were a ‘shortened’ version there were challenges encountered during the data analysis processes.

At the end of the data collection, 59 youth instruments and 107 adult instruments had been completed. Using the first method of data collection described above, 49 youth and 40 adults completed the instrument. In the second method employing door-to-door randomized strategies, 10 youth and 67 adults participated.

Combining all youth and all adult data, the average age of the youth respondents was 16 (range 12 to 20) while the average age of adults was 32 (range 19 to 62). There is an overlap due to where the instrument was completed; for example, if a 19 or 20 year old was attending school, she or he completed the youth version of the instrument and results were analyzed as youth data. In the door-to-door surveying, it was possible for a 19-year old to self-identify as an adult and thus, complete the adult version of the instrument. Future revisions of the instrument may require theoretical consideration of age and whether the youth and adult versions should not have any existing overlap. Cultural considerations, though, would revolve around the older age of Latino youth in school and simultaneously the independent head of household status of Latino men or women at young ages, including those under 18 who already have dependents.

Over 60% of the adults were from Mexico; among the youth nearly half were either from Mexico or born in the U.S. Other countries represented by adults and youth included Peru, Honduras, Ecuador, Nicaragua, and El Salvador. Adults reported residing in the community an average of 5 years compared to an average of 7 for the youth.

When respondents were asked if they knew of a place in the community that could help a Latino adolescent with depression, 20–25% of adults or youth indicated they knew of such a place. Of those who said they knew a place, 60–80% were female.

Rural Pilot Process

The rural data collection was completed primarily through a one-to-one interview format in a home setting or at Centro Campesino. This resulted in the completion of 153 adult instruments and 36 youth. No incentives for participation were provided. Of the adults completing the instrument, 53% of were male and 46% were female. Among youth participants, 58% were male and 41% females. All surveys with the exception of one youth instrument were completed in Spanish. Over 70% of adult respondents were from Mexico, while 15% reported being born in the U.S. Among the youth, almost half were either from Mexico or born in the U.S. and 30% of this cohort reported speaking only Spanish at home. Adults reported living in the community an average of seven years while youth reported living in the community slightly longer, 7.8 years. When respondents were asked if they knew of a place in the community that could help a Latino adolescent with depression, 20% of adults reported knowing a place while 58% of youth indicated they knew of such a place.

Additional data are being analyzed and will be forthcoming in a publication.

Pilot Qualitative Feedback

Consistent qualitative feedback following instrument administration was that participants were excited that these questions were being asked and the issue of mental health was being broached. Adult respondents described the emotional problems they saw in their youth and frequently asked how the data would be used and what the next steps were going to be. When asked what she or he thought of the survey, one youth shared, “It made me think about me and some of the things I do and situations I am in.” Another youth commented, “I thought it was good to get someone thinking about this stuff and get help if they need it.” Constructive comments from youth included, “that is was okay but could have been shorter”, “honestly, I liked it”, and “some of the questions were kind of confusing.”

Adults shared, “I would like there to be more questions focusing on adolescents; for example, how adults talk about this with their kids” and “everything was good- at least for me-I'd like for you to continue like this.” Suggestions for improvement from adults also focused on the clarity of questions and the survey length: “the questions about 'my culture' are a little difficult to understand” and “make it shorter.” These suggestions will be valuable in revising the instrument, clarifying items, and conducting additional piloting to establish the research and practice utility of the instrument.

LESSONS LEARNED

Through the process described above, we created a bilingual instrument for Minnesota’s Latino communities. We built on existing relationships and established new relationships beyond traditional geographic and academic boundaries. Based on our experiences, overwhelmingly positive, we offer the following summary of lessons learned and future steps.

Key lessons learned include:

Flexibility of timelines is critical. Traditional University-driven research often follows predictable timelines due to the high level of ownership and control. When power is truly shared, the CBPR process is time-intensive because it is dependent on collaborative decision-making through extensive communication and mutual trust. For example, unexpected leadership changes within a community partner organization required adjustment of our original timelines, but ultimately resulted in enhanced internal support for the project. Although challenging to traditional University processes, the resulting collaborative product is highly valuable because all partners have equal ownership in the planning, process, and outcomes.

Public and private funding sources must also consider the time-intensive nature of CBPR in planning grant mechanisms to support this type of research. Consistent with prior recommendations,30 funding sources were pursued to support community and university project expenses. University partners obtained separate internal and external funds to hire graduate research assistants and cover expenses. Through a larger project to reduce health disparities, Centro Campesino received funding from a local foundation to hire rural Latino staff to administer the instrument. Urban partners did not receive funding directly but offered in-kind staff resources and meeting space. Funding agencies desiring to support CBPR research need to examine timelines and expectations established under traditional research models as to their realism for CBPR funded activity.

Community partnering agencies experience frequent change that can be unnerving to University partners when it is not anticipated. For example, an urban partner, West Side Community Health Services (WSCHS), experienced logistical constraints stemming primarily from limited staff availability despite being one of the largest Latino-serving health centers in the Twin Cities area. A solution involved using University acquired grant funds to hire a bilingual interviewer to collect pilot data. Leadership at WSCHS supported this process, offering letters for grant applications, developing the clinic’s piloting strategy, and engaging in dissemination of results. Unexpected changes require innovative levels of thinking by all involved. Fast growing Latino communities and responding Latino-serving or Latino-led agencies inherently experience leadership change, staff turnover, and related growing pains. Both the agencies and university partners benefit from flexible, responsive, creative environments as they collaborate and engage one another in meaningful research with direct practice and policy implications.

A facilitative University infrastructure is optimal. In this project, the interdisciplinary efforts resulted from happenstance. A University infrastructure designed to facilitate coordinated interdisciplinary research efforts could minimize redundancy (e.g. IRB application, grant writing) and enhance efficiency. Improved communication among disciplines and with community agencies would ensure that researchers pursuing similar inquiries are not independently engaging the same community stakeholders without coordination. In some institutions this is occurring through development of specific centers housed within Universities that serve to facilitate collaboration between scholars and departments. An example at the University of Minnesota is the Children, Youth, and Family Consortium, which is dedicated to linking child health researchers within the University to each other and the community. Another example is the Program in Health Disparities Research, housed within the Medical School but intended to support interdisciplinary research efforts and community engagement. Additional efforts are taking place currently within the University to facilitate improved coordination of University-community partnerships across schools and departments such as an inventory of community projects. However, due to the large size of the institution (around 50,000 students), we believe significant resources, as well as leadership from central administration will be needed to ensure that a university wide system is successful and sustained.

Institutional Review Board requirements can be difficult for community partners to meet independently and may require university partner support. This is notable for community partners whose non-English speaking staff are actively engaged in the project. Documentation of online IRB training on confidentiality and the consent process was required for all staff administering the instrument. Rural staff aptly requested that the training be available in Spanish. University and community staff then collaborated to provide interpreter services while staff completed the course, which required additional time and computer resources. This experience led us to believe that there may be benefit to offering IRB training designed specifically for community partners. An unexpected action by the University IRB was recommendation to NOT require written consent from participants. The rationale was based on understanding that many of our potential participants were likely to not have legal documentation to be in the U.S., thus experiencing greater caution in providing written signatures on any formal documents. We believe this increased our success in recruiting participants and was an informed decision by our IRB committee that should be sought at other institutions when the research indicates the need.

-

Research is an opportunity for capacity building. The community agencies involved in this project committed staff participation at all levels, including instrument development, pilot implementation, and future interpretation/dissemination of findings. University partners provided knowledge of current literature and educational opportunities for community partners such as IRB training.

Beyond IRB requirements, there is value for community and academic partners in discussing the benefits and challenges to ensuring ethical research, especially when working with Latinos who may have varying legal status. For example, legal language commonly used in consent forms was also perceived by some community partners to be excessively formal and a potential barrier to participation, especially for undocumented Latinos. This concern elicited valuable conversations that led to revision of forms and increased mutual understanding of requirements of research and potential barriers to research participation among Latino communities.

Relationships are foundational and take time. All partnerships had begun months or years before engaging in this specific project. This level of established trust facilitated timely project progression. In-person meetings took place at least monthly and frequent email communication enabled our partnership. Language used for this communication took place in Spanish, English or both, depending on the comfort level of participants. Frequent communication built strong relationships between University partners, who had not worked together previously. CBPR projects involving new partnerships require time to allow such relationships and trust to develop.

NEXT STEPS

Next steps in this project include further analysis of the pilot data and strategies to improve and develop the instrument. Based on the qualitative feedback of participants, the instrument is too lengthy. One revision may be to separate the instrument into a Part A and a Part B in which Part A consists of attitudes and knowledge and Part B is comprised of behaviors. In this way, agencies and researchers will be able to administer one or both parts depending on the research question at hand. Further, larger scale instrument administration is required to have a sample size adequate to conduct reliability and validity analysis. Test and re-test strategies should also be employed. Further, another instrument could be simultaneously administered to facilitate comparing our instrument to an existing gold standard. Because a comprehensive gold standard does not exist, this comparison could occur using sub-scales of the instrument rather than the entire instrument.

CONCLUSION

Community-based participatory research methods are salient for sensitive health topics and varied research objectives, including instrument development. In order to ensure cultural and social relevance of research, community participation is crucial at all stages of research including developing and piloting the research question and survey instrument.

Objective: To develop a mental health survey eliciting perceptions, knowledge, and behaviors of Latino adolescents and adults regarding mental health and available community resources.

Methods: Using a community-based participatory research(CBPR) approach, a survey instrument was developed collaboratively with an interdisciplinary University research team, staff from organizations serving Latinos, and Latino community members from two rural and urban U.S. locations. The survey was developed in response to Latino community requests to gather local data on mental health status and resources. As a community-driven project, the topics included in the survey were selected by community members including depression, domestic violence and knowledge of existing resources. The bi-lingual instrument was revised by community and academic collaborators and back-translated from Spanish to English. Partnering agencies are concurrently pilot testing in rural and urban sites; initial data analysis anticipated Spring of 2007.

Conclusion: Community-based participatory research methods are salient for sensitive topics such as mental health and for varied research objectives, including instrument development. In order to ensure cultural and social relevance of research, community participation is crucial at all stages of research. This paper describes an instrument development and utilization community health research project that employed CBPR; lessons learned and knowledge gained are communicated.

Supplementary Material

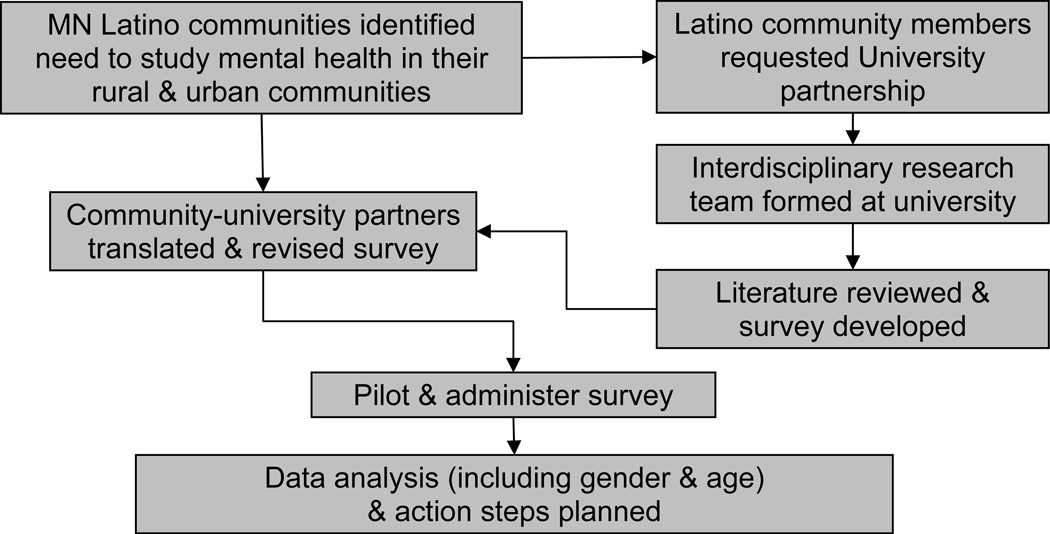

Figure 1. Process of instrument development.

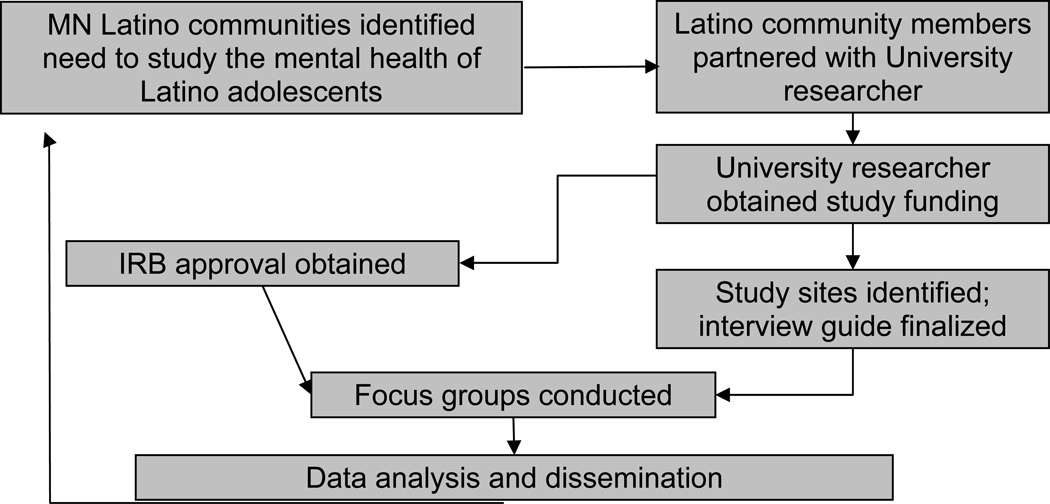

Figure 2.

REFERENCES

- 1.Marotta SA, Garcia JG. Latinos in the United States in 2000. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2003;25:13–34. [Google Scholar]

- 2.State of Minnesota Chicano Latino Affairs Council. Statistical Update: 2006 American Community Survey: The Hispanic/Latino Population in Minnesota. St Paul, MN: Chicano Latino Affairs Council; [Google Scholar]

- 3.U.S. Census Bureau. The Hispanic population in the United States. 2001. pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 4.State of Minnesota Chicano Latino Affairs Council. The Hispanic/Latino Population in Minnesota: Demographic Update 2007. St Paul, MN: Chicano Latino Affairs Council; [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oswald J, Edelman K. Migrant farmworkers and their families in Minnesota: Health and nutritional status and resources, economic contributions, collaborative resources and other issues. St. Paul: Minnesota Department of Health, Center for Health Statistics, Division of Community Health Services; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kielkopf James J. Estimating the economic impact of the Latino workforce in south central Minnesota. Mankato, MN: Center for Rural Policy and Development; 2000. Sep, [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gillapsy T, Hibbs J, et al. Halftime Highlights: Minnesota at Mid-Decade. St Paul, MN: State Demographic Center; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 8.McMurry M. Population Notes: August 2006. St Paul, MN: Minnesota Demographic Center; [Google Scholar]

- 9.Minnesota Department of Health. Populations of Color in Minnesota. Health Status Report. Center for Health Statistics; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gwyther ME, Jenkins M. Migrant farmworker children: Health status, barriers to care, and nursing innovations in health care delivery. Journal of Pediatric Health Care. 1998;12:60–66. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5245(98)90223-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kouyoumdijian H, Zamboanga BL, Hansen DJ. Barriers to community mental health services for Latinos: Treatment considerations. American Psychological Association. 2003;10:394–417. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Timmins CL. The impact of language barriers on the health care of Latinos in the united states: A review of the literature and guidelines for practice. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2002;47:80–96. doi: 10.1016/s1526-9523(02)00218-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flisher AJ, Kramer RA, Grosser RC, et al. Correlates of unmet need for mental health services by children and adolescents. Psychol Med. 1997;27:1145–1154. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797005412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Douglas-Hall A, Koball H. Children of recent immigrants: National and regional trends. 2004:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 15.DHHS. A supplement to mental health: A report of the surgeon general. Washington: Department of Health and Human Services, U.S.; 2001. Mental health: Culture, race, and ethnicity. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rew L, Thomas N, Horner SD, Resnick MD, Beuhring T. Correlates of recent suicide attempts in a triethnic group of adolescents. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2001;33:361–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2001.00361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garcia C, Skay C, Sieving R, Naughton S, Bearinger L. Family and racial factors associated with suicide and emotional distress among Latino students. Journal of School Health. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2008.00334.x. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O'Donnell L, O'Donnell C, Wardlaw DM, Stueve A. Risk and resiliency factors influencing suicidality among urban African American and Latino youth. Am J Community Psychol. 2004;33:37–49. doi: 10.1023/b:ajcp.0000014317.20704.0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Israel B, Schulz A, Parker E, Becker A, Allen A, Guzman J. Critical issues in developing and following community-based participatory research principles. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garcia C. Perceptions of mental health among recently immigrated Mexican adolescents. Iss Mental Health Nurs. 2007;28:37–54. doi: 10.1080/01612840600996257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zayas LH, Lester RJ, Cabassa LJ, Fortuna LR. Why do so many Latina teens attempt suicide? A conceptual model for research. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2005;75:275–287. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.75.2.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fornos L, Mika V, Bayles B, Serrano A, Jimenez R, Villarruel R. A qualitative study of Mexican American adolescents and depression. J Sch Health. 2005;75:162–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lopez S. Mental health care for Latinos: A research agenda to improve the accessibility and quality of mental health care for Latinos. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53:1569–1573. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.12.1569. 25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gryqacz, Joseph G, et al. Evaluating Short-Form Versions of the CES-D for Measuring Depressive Symptoms Among Immigrants From Mexico. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2006;28:404–424. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Remor Eduardo. Psychometric Properties of a European Spanish Version of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) The Spanish Journal of Psychology. 2006;9:86–93. doi: 10.1017/s1138741600006004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bedregal, et al. Psychometric characteristics of a Spanish version of the DAST-10 and the RAGS. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31:309–319. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ping-Hsin Chen, Sue Rovi, Marielos Vega, et al. Screening for domestic violence in a predominantly Hispanic clinical setting. Family Practice. 2005;22:617–623. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmi075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carver Charles S. You Want to Measure Coping But Your Protocol’s Too Long: Consider the Brief COPE. Int J Behav Med. 1997;4:92–100. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garwick AW, Auger S. Participatory action research: The Indian family stories project. Nurs Outlook. 2003;51:261–266. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2003.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.