Abstract

Objective

To determine the rate, extent and clinical significance of neck dilatation after endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR).

Methods

Patients who underwent elective EVAR using bifurcated Zenith (Cook, Bloomington, IN) stent-grafts and had at least 48-months of clinical and radiographic follow-up were included in the present study. Computed tomographic images were analyzed on a 3-dimensional workstation (TeraRecon, San Mateo, CA). Neck diameter was measured 10 mm below the most inferior renal artery, in planes orthogonal to the aorta. Nominal stent graft diameter was obtained from implantation records.

Results

46 patients met the inclusion criteria. Median follow-up was 59 months (range 48-120 months). Neck dilation occurred in all 46 cases. The rate of neck dilation was greatest at early follow-up intervals. At 48-months, median neck dilation was 5.3 mm (range 2.3-9.8 mm). The extent of neck dilation at 48-months correlated with percentage of stent-graft oversizing (Spearman’s rho 0.61, p<0.001). There were no cases of type I endoleak or migration (> 5 mm).

Conclusions

Following EVAR with the Zenith stent-graft, the neck dilates until its diameter approximates the diameter of the stent-graft. Neck dilation was not associated with type I endoleak or migration of the stent-graft.

Introduction

Endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) of abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is associated with less perioperative morbidity and mortality than conventional open repair.1-3 Long-term success depends on the durability of the seal between the stent graft and neck. In theory, neck dilatation could lead to loss of wall contact, resulting in endoleak, aneurysm pressurization, and rupture.

Several authors have described medium-term changes in aneurysm neck diameter after EVAR using a variety of stent grafts.4-11 These studies tended to treat neck dilatation as an all or nothing phenomenon, and focused on its incidence in varying assortments of device types. The only long-term, device-specific data relate to the behavior of a balloon-expanded stent graft, which appears to produce a very low rate of neck dilatation.11 The other studies suggest that following the implantation of a self-expanding stent graft, neck dilatation would continue to proceed relentlessly with an ever-increasing rate of serious complications, especially in the absence of active fixation.6-9 However, none of these studies examined the magnitude and rate of change of neck dilatation long after EVAR. The present study attempts to fill this gap by describing the rate, extent, and clinical significance of aortic neck dilatation after EVAR using the Zenith stent-graft in patients with at least 4-years of follow-up.

Methods

Between October 1998 and November 2004, 272 patients underwent elective EVAR using bifurcated Zenith (Cook, Bloomington, IN) stent-grafts at the University of California, San Francisco Medical Center. Of these, 46 patients had at least 4-years of clinical and radiographic follow-up and are included in the current study. Subjects were excluded from the analysis if the operation was urgent/emergent or involved the implantation of uni-iliac, fenestrated, or multi-branched devices. Routine follow-up included computed tomography (CT) at 1-month, 6-months, 12-months, and annually thereafter. Patient demographic data and information on nominal stent-graft diameter were obtained from a prospectively maintained registry. Stents grafts were sized (or oversized) according to the preferences of individual surgeons.

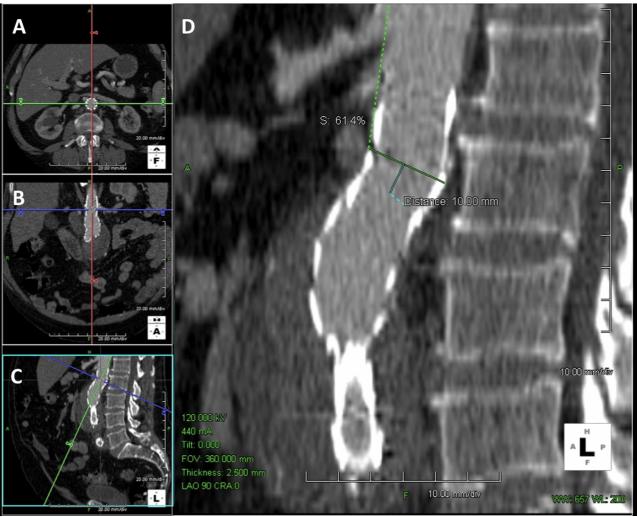

CT images were analyzed on a three-dimensional workstation (TeraRecon, San Mateo, CA). Migration was defined as >5 mm movement of the proximal stent relative to the renal arteries, or any movement requiring a secondary procedure.12 Aortic neck diameter was measured 10 mm below the most inferior renal artery in planes orthogonal to the aorta (Figure 1). The inner diameter of the aortic neck was measured on the major and minor axis. The nominal stent graft diameter was recorded as the main body stent graft diameter, as provided by the manufacturer. Actual device diameter was measured in the unconstrained portion of the stent graft in the aneurysm sac.

Figure 1.

Measurement of proximal aneurysm neck. The level of the most inferior renal artery was identified in the axial (Panel A), coronal (Panel B), and sagital planes (Panel C). The aortic neck was measured 10 mm inferior to the most inferior renal artery in planes orthogonal to the aorta, in the mid portion of the first covered stent (Panel D).

The rate of neck dilatation was determined by dividing the change in neck diameter (from baseline) by the duration of follow-up. The association between neck diameter at 48 months and the percentage of oversizing, as well as the association between neck diameter at 48-months and aneurysm size was assessed using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient. In order to allow us to compare patients with a wide range of neck and stent graft diameters, neck diameter was normalized to nominal stent graft diameter (normalized diameter = aortic neck diameter/nominal stent graft diameter). Statistical analysis was performed using STATA version 11 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

The mean age of the cohort was 74.6 ± 7.5 years, and 89% were men. Median aortic neck diameter, at the time of stent graft placement, was 21.5 mm (range 18.1-27.9 mm), and median nominal device diameter was 28 mm (range 22-32 mm), resulting in a mean oversizing of 29% ± 10%. Median follow-up was 59 months (range 48 -120 months).

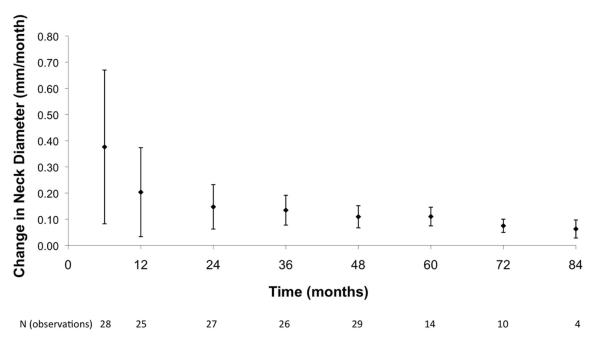

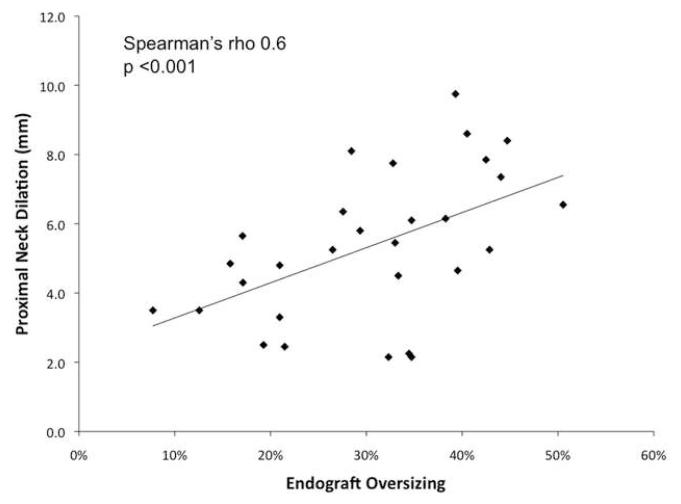

No patients in this cohort had a type I endoleak at any point in follow-up, and there was no device migration (> 5 mm). The neck dilated in all patients. The rate of neck dilation (Figure 2) was greater in early follow-up than in late (≥ 48 months) follow-up. At 48 months, median neck dilation was 5.3 mm (range 2.3-9.8 mm). The extent of neck dilation at 48-months correlated with the percentage of stent-graft oversizing, (Figure 3; Spearman’s rho 0.61, p<0.001) but did not correlate with aneurysm size (p=0.3).

Figure 2.

Rate (mm/month) of proximal neck dilation after EVAR (mean ± standard deviation).

Figure 3.

Relationship between the percentage of endograft oversizing and amount of proximal neck dilation at 48-months of follow-up.

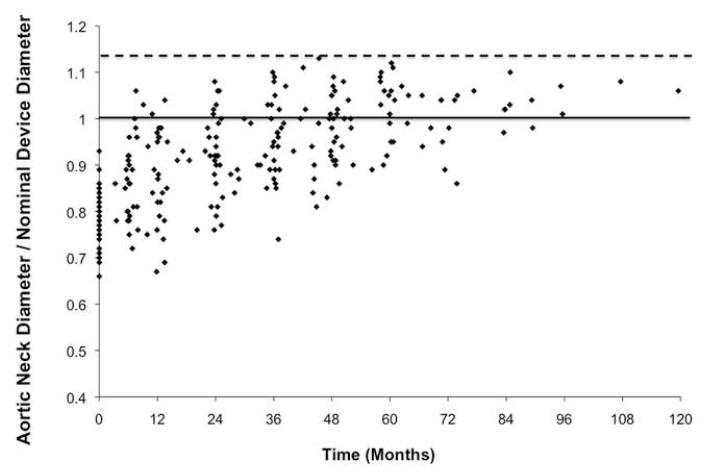

Figure 4 demonstrates the normalized aortic neck diameter over time. Since there were no type I endoleaks or device migration in this cohort, we were surprised to find that the aortic neck expanded by as much as 113% of nominal stent graft diameter (Figure 4). This led us to question whether the nominal stent graft diameter represented the actual stent graft diameter. When we measured the actual stent-graft diameter on the CT scans at 48 months, we found that this was a median of 2.8 mm, or 10%, larger than the median nominal stent graft diameter.

Figure 4.

Normalized aortic neck diameter (aortic neck diameter/nominal stent graft diameter) over time.

Discussion

Durable EVAR depends on a persistent seal between the proximal end of the stent graft and a non-dilated segment of infrarenal aorta (the neck). This study, like others before it4-11 demonstrated a high incidence of neck dilatation following EVAR with a self-expanding stent graft. We observed some degree of neck dilatation at the 4-year follow-up in all cases. This rate is higher than the 20%8 to 30% seen in previous studies, probably because the follow-up is longer.

Since stent graft function depends on contact between the outside of the stent graft and the inside of the neck, one might expect that the universal neck dilatation would ultimately result in universal failure. Yet large studies have shown that secondary endoleak remains a relatively rare complication for many years after EVAR, if only with certain devices.13, 14 The current study helps to explain this apparent disparity between the incidence of neck dilatation and the incidence of long-term failure. Following repair with the Zenith stent graft, the diameter of the neck increased rapidly at early time points, and slowly at later time points. At no point did the diameter of the neck exceed the actual diameter of the stent graft. The diameter of the neck exceeded the nominal diameter of the stent graft but only because the nominal diameter underestimated the actual diameter.

We speculate that when the stent graft, or part of the stent graft, reaches maximum diameter, its inelastic woven polyester covering loses the capacity to expand and contract with the phases of the cardiac cycle, and ceases to transmit force to the aortic wall. This protective effect is likely to be device-specific and dependent upon active barb-mediated attachment. While the loss of a stent graft’s potential for outward expansion probably enhances the stability of the neck, the corresponding reduction in friction would undermine the stability of any stent graft lacking a suprarenal stent for attachment in the pararenal aorta, or barbs for attachment in the neck.8, 9

If, as we believe, the fully expanded stent graft imposes a limit on neck diameter, it is not surprising that the potential for dilatation of the neck depends on the potential for dilatation of the stent graft within the neck; hence, the correlation between oversizing and neck dilatation. A greatly oversized stent graft can expand a lot before reaching its limit, whereas a barely oversized stent graft can expand very little.

The findings of the current study are limited by the small size of the study cohort, which results in part from the combined effects of patient demographics and the requirement for long follow-up. In 1998, when the study started, the Zenith stent graft was not approved for general use in the United States. At the time, our IDE protocol limited EVAR to high-risk patients with short life-expectancy. Many of these patients did not live long enough to qualify for inclusion in this study. It is important to note, however, that these patients did not die from aneurysm-related causes. As of 2007, when the entire underlying cohort was last examined in detail,13 there were no instances of secondary type I endoleak and no conversions to open surgery for migration. Had that not been the case, the current study would suffer from selection bias through the elimination of patients who had serious complications of neck dilatation. We also recognize that the current data apply only to patients treated with the Zenith stent graft. Other patient groups and other stent grafts may have different rates of neck dilatation, migration, and endoleak.

Conclusion

Following EVAR with the Zenith stent-graft, the aortic neck dilates until limited by the fully expanded stent-graft. Expansion of the aortic neck to match the size of the implanted stent-graft is not associated with type I endoleak or migration of the stent-graft.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Endovascular aneurysm repair versus open repair in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm (EVAR trial 1): randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;365:2179–86. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66627-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blankensteijn JD, de Jong SE, Prinssen M, et al. Two-year outcomes after conventional or endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2398–405. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schermerhorn ML, O’Malley AJ, Jhaveri A, Cotterill P, Pomposelli F, Landon BE. Endovascular vs. open repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms in the Medicare population. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:464–74. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0707348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diehm N, Hobo R, Baumgartner I, et al. Influence of pulmonary status and diabetes mellitus on aortic neck dilatation following endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms: a EUROSTAR report. J Endovasc Ther. 2007;14:122–9. doi: 10.1177/152660280701400202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cao P, Verzini F, Parlani G, et al. Predictive factors and clinical consequences of proximal aortic neck dilatation in 230 patients undergoing abdominal aorta aneurysm repair with self-expandable stent-grafts. J Vasc Surg. 2003;37:1200–5. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(02)75340-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dalainas I, Nano G, Bianchi P, et al. Aortic neck dilatation and endograft migration are correlated with self-expanding endografts. J Endovasc Ther. 2007;14:318–23. doi: 10.1583/06-2007.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sampaio SM, Panneton JM, Mozes G, et al. Aortic neck dilation after endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair: should oversizing be blamed? Ann Vasc Surg. 2006;20:338–45. doi: 10.1007/s10016-006-9067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dillavou ED, Muluk S, Makaroun MS. Is neck dilatation after endovascular aneurysm repair graft dependent? Results of 4 US Phase II trials. Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2005;39:47–54. doi: 10.1177/153857440503900105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Napoli V, Sardella SG, Bargellini I, et al. Evaluation of the proximal aortic neck enlargement following endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm: 3-years experience. Eur Radiol. 2003;13:1962–71. doi: 10.1007/s00330-003-1859-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Badran MF, Gould DA, Raza I, et al. Aneurysm neck diameter after endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2002;13:887–92. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(07)61771-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peirano MA, Bertoni HG, Chikiar DS, et al. Size of the proximal neck in AAAs treated with balloon-expandable stent-grafts: CTA findings in mid- to long-term follow-up. J Endovasc Ther. 2009;16:696–707. doi: 10.1583/09-2711.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chaikof EL, Blankensteijn JD, Harris PL, et al. Reporting standards for endovascular aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2002;35:1048–60. doi: 10.1067/mva.2002.123763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hiramoto JS, Reilly LM, Schneider DB, Sivamurthy N, Rapp JH, Chuter TA. Long-term outcome and reintervention after endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair using the Zenith stent graft. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45:461–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.11.034. discussion 5-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Marrewijk CJ, Leurs LJ, Vallabhaneni SR, Harris PL, Buth J, Laheij RJ. Risk-adjusted outcome analysis of endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair in a large population: how do stent-grafts compare? J Endovasc Ther. 2005;12:417–29. doi: 10.1583/05-1530R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]