Abstract

Soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH) is a bifunctional enzyme that has a C-terminus epoxide hydrolase domain and an N-terminus phosphatase domain. The endogenous substrates of epoxide hydrolase are known to be epoxyeicosatrienoic acids, but the endogenous substrates of the phosphatase activity are not well understood. In this study, to explore the substrates of sEH, we investigated the inhibition of the phosphatase activity of sEH toward 4-methylumbelliferyl phosphate by using lecithin and its hydrolyzed products. Although lecithin itself did not inhibit the phosphatase activity, the hydrolyzed lecithin significantly inhibited it, suggesting that lysophospholipid or fatty acid can inhibit it. Next, we investigated the inhibition of phosphatase activity by lysophosphatidyl choline, palmitoyl lysophosphatidic acid, monopalmitoyl glycerol, and palmitic acid. Palmitoyl lysophosphatidic acid and fatty acid efficiently inhibited phosphatase activity, suggesting that lysophosphatidic acids (LPAs) are substrates for the phosphatase activity of sEH. As expected, palmitoyl, stearoyl, oleoyl, and arachidonoyl LPAs were efficiently dephosphorylated by sEH (Km, 3–7 μM; Vmax, 150–193 nmol/min/mg). These results suggest that LPAs are substrates of sEH, which may regulate physiological functions of cells via their metabolism.

Keywords: dephosphorylation, epoxyeicosatrienoic acid, fatty acid

Soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH) is a bifunctional enzyme with a C-terminus epoxide hydrolase domain and an N-terminus phosphatase domain. The substrates of epoxide hydrolase are endogenous epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs) generated by cytochrome P450 epoxygenases (1). EETs have been shown to possess a variety of biological effects, such as vasodilation, antiinflammation, angiogenesis, and antiplatelet aggregation, leading to protection of the renal vasculature from injury and cardiovascular diseases (2–4). EETs are converted by sEH to the corresponding diols, dihydroxyeicosatrienoic acids (DHETs), which are less bioactive lipids or have different effects from EETs. Therefore, the inhibition of sEH is a therapeutic target in the treatment of vascular diseases (2, 5).

The N-terminal domain of sEH was identified as a phosphatase by Cronin et al. (6) and Newman et al. (7). Its phosphatase has sequence similarity to the haloacid dehalogenase (HAD) superfamily, which includes dehalogenases, phosphonatases, phosphomutases, phosphatases, and ATPases. This family possesses a conserved Rossmann fold containing four loops (loops 1–4), which make up the catalytic scaffold (8). Loop 1 contains a highly conserved DXDX(T/V) motif, in which the initial Asp is the nucleophile to attack phosphate. Loop 2 and loop 3 have Ser/Thr and Lys/Arg, which are the binding sites of substrate phosphate, and loop 4 contains two Asp residues binding to Mg2+. The HAD family has three subfamilies (I–III), based on the position of the cap domain, that contribute to the recognition of substrates. The phosphatase domain of sEH belongs to the HAD class I subfamily, which has a small cap domain between loop 1 and loop 2 (9). Because the cap domain encloses the active site of the core domain and limits the insertion of the substrate, the substrate of sEH is predicted to be small. Newman et al. (7) hypothesized that dihydroxy fatty acid phosphates are substrates for the phosphatase of sEH because sEH metabolizes the EETs or linoleic acid epoxide to form the corresponding diols. Indeed, several phosphorylated fatty acids, especially threo-9,10-phosphonooxyhydroxy-octadecanoic acid (PHO), are dephosphorylated by sEH. Gomez et al. (10) also showed the crystal structure of sEH with PHO and suggested that the active site of sEH has a hydrophobic cleft and a long hydrophobic tunnel that accommodate the binding of an aliphatic substrate (10). However, lipid phosphates such as PHO are not known to exist in vivo. Tran et al. (11) and Enayetallah et al. (12) found that sEH dephosphorylated isoprenoid phosphates, which are precursors of cholesterol biosynthesis and a source of protein isoprenylation. It has also been shown that, in sEH knockout mice, the plasma cholesterol level is decreased compared with that in wild-type mice (13). The details of the phosphatase activity of sEH on endogenous substrates remain unknown.

Previously we have shown that the knockdown of sEH in Hep3B cells promoted cell growth and increased the level of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and that overexpression of sEH decreased them both (14). Overexpression of a sEH mutant lacking the phosphatase activity did not have these effects, indicating that the phosphatase activity of sEH is involved in these events. Therefore, the substrates for the phosphatase activity of sEH may be lipid signaling molecules, which activate the growth of cells (15).

Phospholipids are components of the cell membrane and generate a variety of bioactive lipid molecules that play critical roles in cell signaling and control the growth and survival of cells. In the present study, we explored the substrates for the phosphatase activity of sEH. We used an assay system with 4-methylumbelliferyl phosphate (4-MUP) and added several kinds of phospholipids and their hydrolyzed products. The hydrolyzed products of lecithin or lysophosphatidyl choline (LPTC) inhibited the phosphatase activity of sEH. Therefore, we thought that the hydrolyzed products might include substrates for the phosphatase activity of sEH. Finally, we found that lysophosphatidic acids (LPAs) are good substrates of sEH and that fatty acids were good inhibitors for the phosphatase activity of sEH. LPAs are lipid signaling molecules controlling cell proliferation and cell motility through the activation of G-coupled cell-surface LPA receptors (16, 17). Intracellular LPA can activate internal signaling cascades, activating peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-γ (18) and nuclear LPA1 receptors (19).

In this study, we investigated the phosphatase activity of sEH toward several phospholipids, including LPAs. We also investigated the inhibitory effects of fatty acids on the phosphatase activity of sEH.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Lecithin from egg yolk, dodecyl phosphate, sodium laurate, 1-hexadecanol, and 4-methylumbelliferyl phosphate were purchased from Wako Pure Chemicals (Osaka, Japan). Palmitoyl-L-α-lysophosphatidic acid (1-hexadecanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphate) sodium salt was from Doosan Serdary Reserach Laboratories (Toronto, Ontario, Canada). Oleoyl L-α-lysophosphatidic acid (1-octadecenoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphate) sodium salt and (3-phenyl-oxiranyl)-acetic acid cyano-(6-methoxynaphthalen-2-yl)-methyl ester were from Cayman Chemical Co. (Ann Arbor, MI). Stearoyl L-α-lysophosphatidic acid (1-octadecanoyl-sn glycerol-3-phosphate) sodium salt and 1-octadecyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphate ammonium salt were from Avanti Polar lipids (Birmingham, AL). Geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate ammonium salt, palmitoyl glycerol, stearic acid, and palmitic acid were from Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO). Arachidonoyl L-α-lysophosphatidic acid sodium salt and arachidoyl L-α-lysophosphatidic acid sodium salt were from Echelon Biosciences Inc. (Salt Lake, UT). Attophos was from Promega (Madison, WI). Sphingosine-1-phosphate was kindly provided by Professor Katsumura of Kwansei Gakuin University.

Preparation of sEH constructs and purification of sEH protein

Human wild type (WT) or phosphatase mutant (Asp 9 Ala) of sEH cDNA / pcDNA3.1(+) were constructed previously (14) and subcloned into the pET-21a(+) vector. For the construction of the sEH N-terminal domain (amino acid 1–221), the N-terminal fragment was amplified by PCR with the primers 5′-GGAATTCCATATGACGCTGCGCGCGGCCGT-3′ (forward primer; underline, NdeI site; double underline, start codon) and 5′-AAA CTCGAG AAGCTGGATTCCGGTCACTT-3′ (reverse primer; nucleotides 644–663; underline, XhoI site). The fragment was digested with NdeI and XhoI and ligated into pET-21a(+). Escherichia coli (BL21(DE3) codon+) was transformed with these plasmids and cultured for 24 h at 25°C. Protein was purified with a Ni-NTA agarose column (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Purified protein was dialyzed against 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5). The purity of purified sEH was checked by SDS-PAGE, and the proteins were stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue. The purity of WT, phosphatase mutant, or N-terminal domain of sEH was more than 95%.

Inhibition of phosphatase activity of sEH

sEH (5 μg) was incubated with 50 μM 4-MUP in 25 mM Bis Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.0) containing BSA (0.1 mg/ml) and 1 mM MgCl2 at 37°C in the absence or presence of lecithin, LPTC, palmitoyl LPA (p-LPA), palmitoyl glycerol, or fatty acids. To hydrolyze lecithin and LPTC, they were heated at 80°C for 20 min in a 30 mM NaOH solution. Fluorescence of 4-methylumbelliferone was measured every 5 min for 30 min with an EnVision 2104 Multilabel Reader at 330 nm (excitation) and 465 nm (emission). To measure the phosphatase activity with Attophos as a substrate, sEH (5 μg) was incubated in the buffer described above at 30°C for 5 min in the absence or presence of 40 μM stearic acid, palmitic acid, lauric acid, or 1-hexadecanol. Then, Attophos (final 50 μM) was added, and the fluorescence of the hydrolyzed product, 2′-[2-benzothiazoyl]6′-hydroxybenzothiazole, was measured every 1 min for 5 min at 435 nm and 555 nm. For the epoxide hydrolase activity, sEH (1 μg) was incubated with a fluorescent substrate, cyano-(6-methoxynaphthalen-2-yl)-methyl ester (final 25 μM), in 25 mM Bis Tris–HCl (pH 7.0) containing BSA (0.1 mg/ml) at 30°C in the absence or presence of stearoyl LPA (s-LPA), stearic acid, palmitic acid, or lauric acid. The fluorescence of the reaction product, 6-methoxy-2-naphthaldehyde, was measured every 1 min for 30 min at 330 nm and 465 nm. The enzymatic activity of sEH was determined from the initial slope of the time course line.

Dephosphorylation of LPA by sEH assessed with LC-MS

Purified WT or phosphatase mutant of sEH (2.5 μg) was incubated for 5 min at 37°C in 500 μl of 25 mM Bis Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.0) containing BSA (0.1 mg/ml) and 1 mM MgCl2. s-LPA (20 μM) was added and incubated for 15 min at 37°C. To determine the kinetic values, sEH (3 μg) was incubated with LPAs (final concentration, 1, 3, 5, 10, or 20 μM) for 5 min at 37°C. LPA and monoacyl glycerol were extracted by the Bligh Dyer method as follows. The reaction was stopped with 2.3 ml of chloroform/methanol (1:2, v/v) and 100 μl of 1.2 N HCl, and dodecyl phosphate (3 nmol) was added as an internal standard. The mixture was left to stand for 10 min, and then 0.75 ml each of chloroform and water were added. After centrifugation at 1500 × g for 10 min, the lower organic layer was transferred and dried under nitrogen gas. The resulting residue was dissolved in 50% methanol and analyzed by UPLC/electrospray ionization (ESI)/MS. The chromatography was performed with a C18 reversed phase column (TSK-GEL ODS-140HTP, 2.1 × 100 mm) and the UPLC system (ACQUITY UPLC system, Waters, Milford, MA). To detect LPA, mobile phase A (10 mM ammonium acetate and 1% acetic acid) and mobile phase B (99% methanol, 10 mM ammonium acetate, and 1% acetic acid) were used (20). Ammonium acetate was removed from the mobile phase to detect its metabolite, monoacyl glycerol. Chromatography was done at a flow rate of 0.2 ml/min, with a linear gradient from 50% A to 100% B for 20 min. Mass spectrometry was carried out using a Nanofrontier LD mass spectrometer (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) and ionized by ESI. ESI was accomplished in the negative ion mode with a spray potential of 2950 V for the detection of LPA or in the positive ion mode with a spray potential of 5500 V for monoacyl glycerol. The analytes were detected by a tandem TOF monitored by total ion, m/z 437.3 or 409.3 for s-LPA or p-LPA, and m/z 381.4 or 353.4 for stearoyl glycerol or palmitoyl glycerol, respectively. The amount of produced monoacyl glycerol was determined by a calibration curve prepared with authentic stearoyl glycerol or palmitoyl glycerol.

Dephosphorylation assay of sEH with malachite green

The phosphatase activity of sEH toward LPAs, phosphatidic acids (PAs), sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P), or geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate (GGPP) was detected by Biomol green assay (Enzo Life Science, Plymouth Meeting, PA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Purified sEH (0.3 μg) was preincubated for 5 min at 37°C in 25 mM Bis Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.0) containing BSA (0.1 mg/ml) and 1 mM MgCl2. Each substrate was added at various concentrations (1–20 μM) and incubated for 5 min at 37°C. However, because the activities toward arachidoyl or alkyl LPA, PAs, S1P, and GGPP were very low or not detected, reactions were done with an increased concentration of sEH (0.5 μg for alkyl LPA and GGPP and 0.8 μg for arachidoyl LPA, S1P, and PAs) and substrates (1–80 μM). The reaction was stopped by addition of Biomol green reagent and held at room temperature for 60 min. The resulting green color was measured with the EnVision 2104 Multilabel Reader (Perkin Elmer, Foster City, CA) at 630 nm. The concentration of phosphate released was determined using a calibration curve with an inorganic phosphate as a standard. The phosphatase activity of sEH toward s-LPA was also measured in the presence of Triton X-100. s-LPA (5 mM) was suspended in 1% Triton X-100 and sonicated for 5 min, and sEH (0.3 μg) was incubated with s-LPA (final 10 μM) for 5 min at a final concentration of Triton X-100 of 0 to 0.1%.

Statistics and kinetics

The kinetic parameters Km and Vmax were obtained using Prism Graphpad enzyme kinetics software. The statistical analysis was done with Student's t-test, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Inhibition of the phosphatase activity of sEH by phospholipids

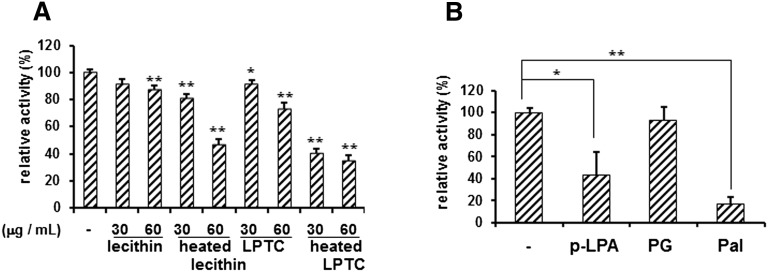

Glycerophospholipids are the major lipid component of most cell membranes. To explore the substrates for the phosphatase activity of sEH, we investigated the inhibitory effect of lecithin from egg yolk and its hydrolyzed products with a synthetic substrate, 4-MUP. Lecithin was heated in a weak alkaline solution to examine the effects of its hydrolyzed products. Although lecithin did not affect the phosphatase activity of sEH, heated lecithin did (Fig. 1A) . Hydrolyzed products of lecithin may include LPTC, fatty acids, etc. Therefore, we used LPTC, which inhibited the sEH phosphatase activity in a dose-dependent manner, suggesting that a structure like a lysophospholipid can bind to the active site of the phosphatase domain of sEH. Furthermore, heated LPTC also inhibited it, suggesting that hydrolyzed fatty acid can inhibit the phosphatase activity of sEH. Because lipid phosphates can be substrates of phosphatase, p-LPA was used in this assay. p-LPA inhibited the phosphatase activity of sEH, but the dephosphorylated product, palmitoyl glycerol, did not (Fig. 1B). Palmitic acid also significantly inhibited the activity.

Fig. 1.

Inhibition of phosphatase activity of sEH toward 4-MUP by phospholipids. A: sEH (5 μg) was incubated with 50 μM 4-MUP in the absence or presence of 30 or 60 μg/ml of lecithin, LPTC, and these lipids heated at 80°C for 20 min. Fluorescence of 4-methylumbelliferone was measured every 5 min for 30 min at 330 nm (excitation) and 465 nm (emission). The y axis indicates the percentage for the activity of sEH with that in the absence of lipids. B: The phosphatase activity of sEH in the presence of 40 μM p-LPA, palmitoyl glycerol, or palmitic acid. LPTC, lysophosphatidic acid; p-LPA, palmitoyl lysophosphatidic acid; PG, palmitoyl glycerol; Pal, palmitic acid. Values are given as the mean ± SD for three separate experiments. *Significantly different from control (P < 0.05). **Significantly different from control (P < 0.01).

Dephosphorylation of s-LPA by sEH

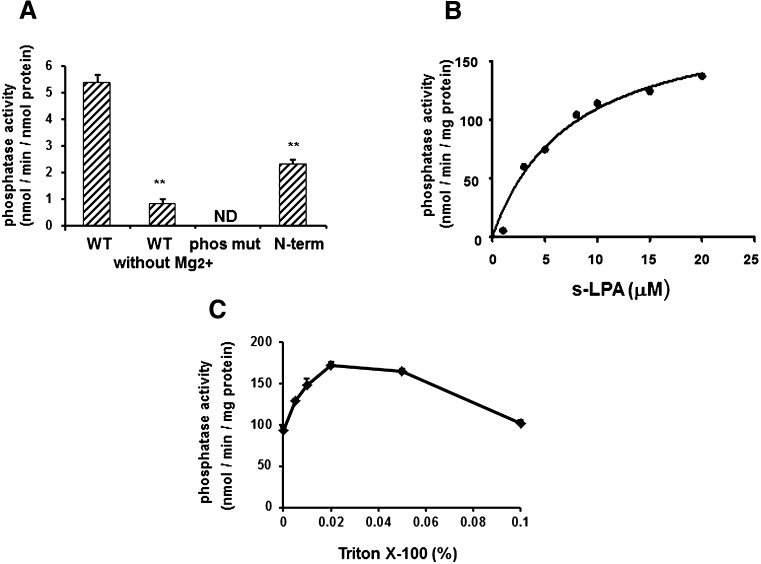

Because LPA can inhibit the phosphatase activity of sEH, we investigated the dephosphorylation of LPA by sEH. s-LPA was incubated with a recombinant WT sEH or phosphatase mutant sEH, in which the catalytic Asp9 was changed to Ala, and detected by UPLC/ESI/MS. The incubation of s-LPA with WT sEH decreased the amount of s-LPA but not that with the mutant sEH (Supplementary Fig. S1A), and the dephosphorylated form of s-LPA, stearoyl glycerol, was detected by the incubation with WT sEH (Supplementary Fig. S1B). The phosphatase activity of sEH toward s-LPA was also detected by malachite green assay (Fig. 2A). The activity of sEH toward s-LPA was significantly decreased without Mg2+. The phosphatase mutant of sEH had no activity, and the N-terminal domain of sEH had phosphatase activity, although less than the full-length sEH. Furthermore, the phosphatase activity was measured with several concentrations of s-LPA and exhibited a Michaelis-Menten curve (Fig. 2B). These results suggested that the malachite green assay can detect the phosphatase activity of sEH and that sEH has Michaelis-Menten type activity toward LPAs. Next, the activity of sEH was measured in the presence of Triton X-100. A transmembrane LPA phosphatase, lipid phosphate phosphatase 1, has been shown to need the micelle formation of Triton X-100 (0.1–0.3%) with LPAs for its activity (21). The highest activity of sEH toward s-LPA was observed in 0.02% Triton X-100, and the increased concentration of Triton-X100 decreased the activity (Fig. 2C). The critical micelle concentration of this detergent is about 0.015%, suggesting that the micelle is not needed for the activity of sEH and that the increased activity of sEH is due to the increased solubility of LPAs.

Fig. 2.

The phosphatase activity of sEH using the malachite green assay. A: The full-length (4.7 pmol: 0.3 μg), phosphatase mutant (4.7 pmol: 0.3 μg), or N-terminal domain (4.7 pmol: 0.12 μg) of sEH was incubated with 10 μM s-LPA in the absence or presence of 1 mM MgCl2 at 37°C for 5 min. The released phosphate was detected with malachite green. B: sEH (0.3 μg) was reacted with s-LPA (1–20 μM) at 37°C for 5 min. C: The phosphatase activity of sEH was measured in the presence of several concentrations of Triton X-100. ND, not detected. Values are given as the mean ± SD for three separate experiments. **Significantly different from control (P < 0.01).

Kinetic analysis of phospholipids by sEH

The kinetic parameters of sEH toward several phospholipids were determined (Table 1). sEH efficiently dephosphorylated LPAs, and similar kinetics were observed for p-LPA (C16:0), s-LPA (C18:0), o-LPA (C18:1), and arachidonoyl LPA (C20:4), with Km values of 3–7 μM and Vmax values of 150–193 nmol/min/mg protein. The kinetic parameters for p-LPA and s-LPA were also determined by LC-MS (given in parentheses in Table 1), and these values were similar to those determined by malachite green assay. Arachidoyl LPA (C20:0) was a poor substrate, with a 5-fold lower Vmax value than the other acyl LPAs, although their Km values were similar. The Km value for octadecyl-sn-glycero phosphate (C18:0) was higher than that of acyl LPAs, such as s-LPA. The carbonyl group in LPA may be important for the high affinity with sEH. The phosphatase activities of sEH toward dipalmitoyl or distearoyl PA were very low, and their kinetic values could not be determined in this study. The activity toward S1P, which is a lysolipid of sphingolipid, was also lower than LPAs, suggesting that lyso-glycerophospholipids are selective for the phosphatase activity of sEH. The activity toward GGPP, which is an isoprenoid phosphate, was also lower than that toward LPAs.

TABLE 1.

Kinetic analysis of phosphatase activity of sEH toward several phospholipids

| Km (μM) | Vmax (nmol/min/mg) | Vmax/Km | |

| Palmitoyl-LPA | 3.0 ± 0.7 (6.4 ± 2.4) | 150.4 ± 11.6 (218.9 ± 33.0) | 49.5 |

| Stearoyl-LPA | 6.4 ± 1.8 (6.8 ± 1.6) | 193.5 ± 20.2 (229.1 ± 22.6) | 30.2 |

| Oleoyl-LPA | 6.2 ± 1.5 | 191.6 ± 22.7 | 31.0 |

| Arachidonoyl-LPA | 5.9 ± 0.6 | 157.9 ± 4.6 | 26.9 |

| Arachidoyl-LPA | 5.3 ± 1.6 | 26.8 ± 1.1 | 5.1 |

| 1-alkyl LPA (C18:0) | 23.5 ± 3.0 | 171.1 ± 10.2 | 7.3 |

| Dipalmitoyl-PA | ND | ND | ND |

| Distearoyl-PA | ND | ND | ND |

| Sphingosine-1-phosphate | 14.8 ± 1.2 | 60.6 ± 0.9 | 4.1 |

| Geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate | 20.9 ± 5.7 | 101.3 ± 11.4 | 4.8 |

The phosphatase activity of sEH was detected by malachite green, and the kinetic parameters of sEH for several phospholipids were analyzed. Km and Vmax values of sEH for s-LPA and p-LPA were determined by LC-MS and are shown in parentheses. The kinetic values were calculated using Prism Graphpad enzyme kinetics software. ND, not detected.

Inhibition of the phosphatase activity of sEH by fatty acids

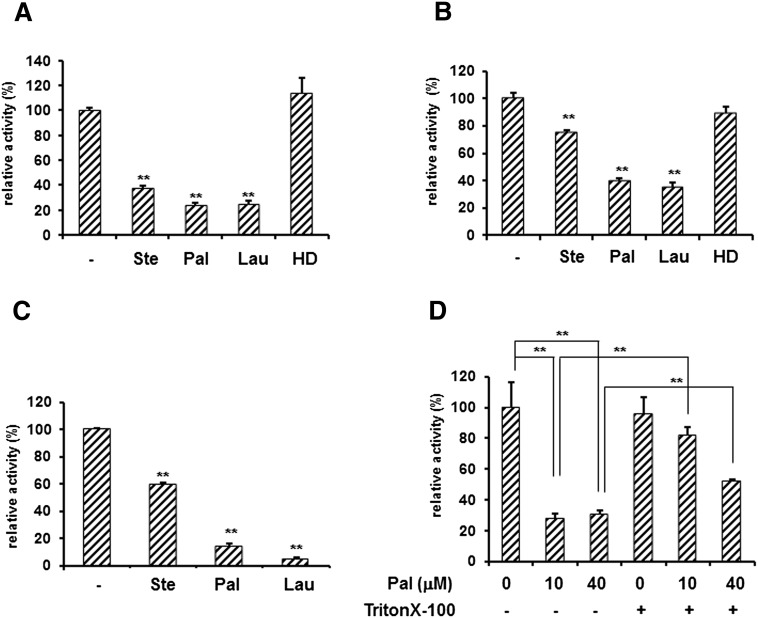

Hydrolyzed LPTC significantly inhibited the phosphatase activity of sEH, suggesting that fatty acids hydrolyzed from LPTC inhibited it. Next, we investigated the effects of fatty acids on the phosphatase activity of sEH toward 4-MUP. Stearic acid (C18), palmitic acid (C16), and lauric acid (C12) significantly inhibited the phosphatase activity of sEH (Fig. 3A). However, 1-hexadecanol did not affect sEH activity. These results suggest that the carboxyl group of fatty acids was important for the inhibition. These fatty acids, especially palmitic acid and lauric acid, also strongly inhibited the phosphatase activity of the N-terminal domain of sEH (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, this inhibition was observed in the phosphatase activity with Attophos as a substrate (Fig. 3C). Next, to negate that the inhibition of fatty acids was due to its detergent effect, we examined the effect of fatty acids in the presence of 0.15% Triton X-100. The effect of palmitic acid was canceled by Triton X-100, suggesting that the interaction of palmitic acid with the micelle of Triton X-100 inhibited its effect (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3.

Inhibition of the phosphatase activity of sEH toward 4-MUP or Attophos by fatty acids. A: Full-length sEH (5 μg) was incubated with 50 μM 4-MUP in the absence or presence of fatty acids. Fluorescence of 4-methylumbelliferone was measured every 5 min for 30 min at 330 nm (excitation) and 465 nm (emission). B: Full-length sEH (5 μg) was incubated with 50 μM Attophos in the absence or presence of fatty acids. The fluorescence of the hydrolyzed product was measured every 1 min for 5 min at 435 nm and 555 nm. C: The N-terminal domain of sEH (2 μg) was incubated with 50 μM 4-MUP. D: Full-length sEH (5 μg) was incubated with 50 μM 4-MUP and palmitic acid (0, 10, or 40 μM) in the absence or presence of 0.15% Triton X-100. The y axis indicates the percentage for the activity with that in the absence of fatty acids. Ste, stearic acid; Pal, palmitic acid; Lau, lauric acid; HD, 1-hexadecanol. Values are given as the mean ± SD for three separate experiments. **Significantly different from control (P < 0.01).

Effects of fatty acids on sEH phosphatase activity toward LPA and on epoxide hydrolase activity

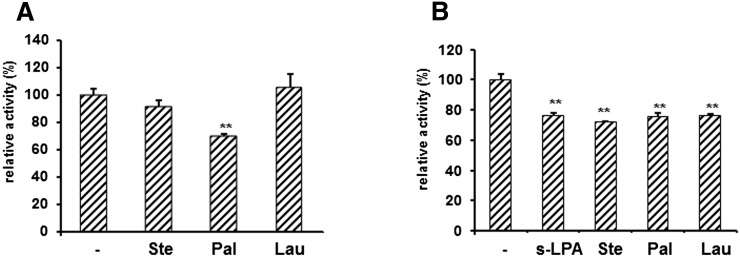

Fatty acids significantly inhibited the sEH phosphatase activity toward 4-MUP and Attophos. Next, inhibition of the phosphatase activity of sEH by fatty acids toward LPA was investigated (Fig. 4A). Palmitic acid slightly inhibited the phosphatase activity of sEH toward s-LPA, and this inhibition was observed toward other acyl LPAs (data not shown). We also investigated the effects of s-LPA and fatty acids on EH activity (Fig. 4B). These lipids slightly inhibited the EH activity by about 20%, and the efficiency of the inhibition was almost the same between s-LPA and fatty acids.

Fig. 4.

Effects of fatty acids on phosphatase activity toward s-LPA and epoxide hydrolase activity toward cyano-(6-methoxynaphthalen-2-yl)-methyl ester (PHOME). A: sEH (0.3 μg) was incubated with 20 μM s-LPA at 37°C for 5 min in the absence or presence of fatty acids (40 μM), and phosphate released was detected with malachite green. B: sEH (1 μg) was incubated with 25 μM PHOME at 30°C in the absence or presence of s-LPA or fatty acids (40 μM), and the fluorescence of 6-methoxy-2-naphthaldehyde was measured every 1 min for 30 min at 330 nm (excitation) and 465 nm (emission). The y axis indicates the percentage of activity with that in the absence of lipids. Ste, stearic acid; Pal, palmitic acid; Lau, lauric acid. Values are given as the mean ± SD for three separate experiments. **Significantly different from control (P < 0.01).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we found LPAs to be good substrates for the phosphatase activity of sEH. Tran et al. (11) and Enayetallah et al. (12) reported that sEH dephosphorylates isoprenoid phosphate, with the turnover rate for farnesyl monophosphate being highest; the Km value was 5.7 or 24.16 μM by LC-MS or phosphate detection assay, respectively. In this study, the Km values of sEH for p-LPA, s-LPA, o-LPA, and arachidonoyl LPA were 3–7 μM, suggesting a similar affinity with isoprenoid phosphate. Furthermore, the ester bond with glycerol is required for LPA to bind to sEH because acyl LPA revealed higher activity than alkyl LPA. On the other hand, the phosphatase activity of sEH toward S1P was lower than that toward LPAs, and the activity toward dipalmitoyl PA or distearoyl PA was not detected, indicating that sEH can selectively hydrolyze LPAs.

LPPs are well known LPA phosphatases that have four isoforms: LPP1, LPP1a, LPP2, and LPP3. LPPs are a six-transmembrane protein, and their active site faces the lumen of endomembrane compartments or the extracellular face of the plasma membrane. LPPs are Mg2+-independent and N-ethylmaleimide-insensitive phosphatases, and hydrolyze a range of lipid phosphomonoesters that includes PA, S1P, ceramide-1-phosphate and diacylglycerol pyrophosphate as well as LPA (22–24).

Lipin/phosphatidic acid phosphohydrolase 1 is known as soluble lipid phosphatase, which is Mg2+-dependent and has nucleophilic aspartate as well as sEH (25, 26). However, the phosphatase activity of mammalian lipin is specific for phosphatidic acid and does not metabolize LPA, ceramide-1-phosphate, or S1P(25), suggesting that sEH is a novel mammalian soluble phosphatase that hydrolyzes LPAs. In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Phm8p, which has a HAD-like domain, was identified as a soluble phosphatase (27). The substrate selectivity of sEH is similar to Phm8p because it dephosphorylates LPAs but not other lipid phosphates. LPAs are mainly produced by secreted autotaxin from lysophosphatidilcholine (28) in extracellular space and activate G-coupled cell-surface LPA receptors. However, recent reports described that within the cells, LPAs are also produced by glycerol 3-phosphate acyltransferanse, which is the rate-limiting step in glycerolipid synthesis (29), and interact with intracellular receptors, peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-γ, and nuclear LPA receptor (18, 19). This suggests the possibility of regulation of intracellular LPAs by soluble phosphatases such as sEH.

Previously we found that the phosphatase activity of sEH decreased the expression level of VEGF and cell growth in Hep3B cells (14). VEGF plays a significant role in tumor development and angiogenesis. Indeed, it has been shown to be decreased sEH levels in renal and hepatic malignant neoplasm (30). The relation between tumor and LPAs is also reported; in ovarian cancer, the levels of LPAs are elevated in malignant effusions of patients (31), and LPAs contribute to the development, progression, and metastasis in ovarian and breast cancer (32, 33). Furthermore, LPAs induce the expression of VEGF in ovarian or prostate cancer cells and hepatoma cells (34, 35). Our finding and these reports suggest the possibility that sEH contribute to the tumor progression through LPA degradation.

In this study, we found that fatty acids significantly inhibited the phosphatase activity of sEH toward synthetic substrates such as 4-MUP and Attophos. Fatty acids that have shorter acyl chain—palmitic acid and lauric acid—efficiently inhibited this activity. These fatty acids did not affect the activity of alkaline phosphatase toward 4-MUP, indicating that fatty acids do not affect the substrate (data not shown). In this study, 1-hexadecanol, which displaced a hydroxyl from a carboxyl group of palmitic acid, had no inhibitory effects. However, dodecyl sulfate inhibited them, and dodecyl phosphate did not (data not shown). Tran et al. (11) reported similar results and showed that the inhibitory effect of dodecyl sulfate on sEH was allosteric. It has been reported that the binding of fatty acids to phosphatidic acid phosphohydrolase 1 induced protein aggregation and inhibited its activity (36). Furthermore, fatty acids did not affect LPA dephosphorylation by sEH. We confirmed a direct binding of lauric acid to sEH by pull down assay using CNBr-activated sepharose coupled with lauric acid, and its binding was prevented in the presence of LPA but not 4-MUP (data not shown). This result suggests that LPA binds to sEH at the same site as that for binding of lauric acid. We speculate that little effect of fatty acids on the activity of sEH toward LPA may be due to a greater affinity of LPA to sEH than to fatty acids. On the other hand, it is possible that 4-MUP binds a separate site from that for binding of lauric acid or has a lower affinity to sEH than it.

The substrates of sEH C-terminal epoxide hydrolase, EETs, are produced from arachidonic acid, which is the product of phospholipase A2 from membrane phospholipid. Phospholipase A2 also produces lysophospholipids, including LPTC, and which are converted to LPA by autotaxin. The common precursor of EETs and LPAs suggests the possibility of an interesting interaction of the two different activities of sEH.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Professor Katsumura of Kwansei Gakuin University for his kind gift of sphingosine-1-phosphate.

Footnotes

Abbreviations:

- EET

- epoxyeicosatrienoic acid

- GGPP

- geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate

- HAD

- haloacid dehalogenase

- LPA

- lysophosphatidic acid

- LPTC

- lysophosphatidyl choline

- 4-MUP

- 4-metylumbelliferyl phosphate

- PA

- phosphatidic acid

- PHO

- threo-9,10-phosphonooxyhydroxy-octadecanoic acid

- p-LPA

- palmitoyl lysophosphatidic acid

- S1P

- sphingosine-1-phosphate

- sEH

- soluble epoxide hydrolase

- s-LPA

- stearoyl lysophosphatidic acid

This study was supported by the Project to Assist Private Universities in Developing Bases for Research of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan and by the Japan Society for the promotion of Science Research Fellowship for young scientist.

The online version of this article (available at http://www.jlr.org) contains supplementary data in the form of two figures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chacos N., Capdevila J., Falck J. R., Manna S., Martin-Wixtrom C., Gill S. S., Hammock B. D., Estabrook R. W. 1983. The reaction of arachidonic acid epoxides (epoxyeicosatrienoic acids) with a cytosolic epoxide hydrolase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 223: 639–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Imig J. D. 2005. Epoxide hydrolase and epoxygenase metabolites as therapeutic targets for renal diseases. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 289: F496–F503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fleming I. 2007. Epoxyeicosatrienoic acids, cell signaling and angiogenesis. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 82: 60–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spector A. A., Norris A. W. 2007. Action of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids on cellular function. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 292: C996–C1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Imig J. D., Hammock B. D. 2009. Soluble epoxide hydrolase as a therapeutic target for cardiovascular diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 8: 794–805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cronin A., Mowbray S., Durk H., Homburg S., Fleming I., Fisslthaler B., Oesch F., Arand M. 2003. The N-terminal domain of mammalian soluble epoxide hydrolase is a phosphatase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100: 1552–1557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Newman J. W., Morisseau C., Harris T. R., Hammock B. D. 2003. The soluble epoxide hydrolase encoded by EPXH2 is a bifunctional enzyme with novel lipid phosphate phosphatase activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100: 1558–1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allen K. N., Dunaway-Mariano D. 2004. Phosphoryl group transfer: evolution of a catalytic scaffold. Trends Biochem. Sci. 29: 495–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cronin A., Homburg S., Durk H., Richter I., Adamska M., Frere F., Arand M. 2008. Insights into the catalytic mechanism of human sEH phosphatase by site-directed mutagenesis and LC-MS/MS analysis. J. Mol. Biol. 383: 627–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gomez G. A., Morisseau C., Hammock B. D., Christianson D. W. 2004. Structure of human epoxide hydrolase reveals mechanistic inferences on bifunctional catalysis in epoxide and phosphate ester hydrolysis. Biochemistry. 43: 4716–4723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tran K. L., Aronov P. A., Tanaka H., Newman J. W., Hammock B. D., Morisseau C. 2005. Lipid sulfates and sulfonates are allosteric competitive inhibitors of the N-terminal phosphatase activity of the mammalian soluble epoxide hydrolase. Biochemistry. 44: 12179–12187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Enayetallah A. E., Grant D. F. 2006. Effects of human soluble epoxide hydrolase polymorphisms on isoprenoid phosphate hydrolysis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 341: 254–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.EnayetAllah A. E., Luria A., Luo B., Tsai H. J., Sura P., Hammock B. D., Grant D. F. 2008. Opposite regulation of cholesterol levels by the phosphatase and hydrolase domains of soluble epoxide hydrolase. J. Biol. Chem. 283: 36592–36598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oguro A., Sakamoto K., Suzuki S., Imaoka S. 2009. Contribution of hydrolase and phosphatase domains in soluble epoxide hydrolase to vascular endothelial growth factor expression and cell growth. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 32: 1962–1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goetzl E. J., An S. 1998. Diversity of cellular receptors and functions for the lysophospholipid growth factors lysophosphatidic acid and sphingosine 1-phosphate. FASEB J. 12: 1589–1598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anliker B., Chun J. 2004. Lysophospholipid G protein-coupled receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 20555–20558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Samadi N., Bekele R., Capatos D., Venkatraman G., Sariahmetoglu M., Brindley D. N. 2011. Regulation of lysophosphatidate signaling by autotaxin and lipid phosphate phosphatases with respect to tumor progression, angiogenesis, metastasis and chemo-resistance. Biochimie. 93: 61–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McIntyre T. M., Pontsler A. V., Silva A. R., St Hilaire A., Xu Y., Hinshaw J. C., Zimmerman G. A., Hama K., Aoki J., Arai H., et al. 2003. Identification of an intracellular receptor for lysophosphatidic acid (LPA): LPA is a transcellular PPARgamma agonist. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100: 131–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gobeil F., Jr, Bernier S. G., Vazquez-Tello A., Brault S., Beauchamp M. H., Quiniou C., Marrache A. M., Checchin D., Sennlaub F., Hou X., et al. 2003. Modulation of pro-inflammatory gene expression by nuclear lysophosphatidic acid receptor type-1. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 38875–38883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee S. H., Raboune S., Walker J. M., Bradshaw H. B. 2010. Distribution of endogenous farnesyl pyrophosphate and four species of lysophosphatidic acid in rodent brain. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 11: 3965–3976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Han G. S., Carman G. M. 2004. Assaying lipid phosphate phosphatase activities. Methods Mol. Biol. 284: 209–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alderton F., Darroch P., Sambi B., McKie A., Ahmed I. S., Pyne N., Pyne S. 2001. G-protein-coupled receptor stimulation of the p42/p44 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway is attenuated by lipid phosphate phosphatases 1, 1a, and 2 in human embryonic kidney 293 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 13452–13460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sigal Y. J., McDermott M. I., Morris A. J. 2005. Integral membrane lipid phosphatases/phosphotransferases: common structure and diverse functions. Biochem. J. 387: 281–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brindley D. N., Pilquil C. 2009. Lipid phosphate phosphatases and signaling. J. Lipid Res. 50(Suppl): S225–S230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Donkor J., Sariahmetoglu M., Dewald J., Brindley D. N., Reue K. 2007. Three mammalian lipins act as phosphatidate phosphatases with distinct tissue expression patterns. J. Biol. Chem. 282: 3450–3457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reue K., Brindley D. N. 2008. Thematic review series: glycerolipids. Multiple roles for lipins/phosphatidate phosphatase enzymes in lipid metabolism. J. Lipid Res. 49: 2493–2503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reddy V. S., Singh A. K., Rajasekharan R. 2008. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae PHM8 gene encodes a soluble magnesium-dependent lysophosphatidic acid phosphatase. J. Biol. Chem. 283: 8846–8854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsuda S., Okudaira S., Moriya-Ito K., Shimamoto C., Tanaka M., Aoki J., Arai H., Murakami-Murofushi K., Kobayashi T. 2006. Cyclic phosphatidic acid is produced by autotaxin in blood. J. Biol. Chem. 281: 26081–26088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stapleton C. M., Mashek D. G., Wang S., Nagle C. A., Cline G. W., Thuillier P., Leesnitzer L. M., Li L. O., Stimmel J. B., Shulman G. I., et al. 2011. Lysophosphatidic acid activates peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-gamma in CHO cells that over-express glycerol 3-phosphate acyltransferase-1. PLoS ONE. 6: e18932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Enayetallah A. E., French R. A., Grant D. F. 2006. Distribution of soluble epoxide hydrolase, cytochrome P450 2C8, 2C9 and 2J2 in human malignant neoplasms. J. Mol. Histol. 37: 133–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baker D. L., Morrison P., Miller B., Riely C. A., Tolley B., Westermann A. M., Bonfrer J. M., Bais E., Moolenaar W. H., Tigyi G. 2002. Plasma lysophosphatidic acid concentration and ovarian cancer. JAMA. 287: 3081–3082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fang X., Gaudette D., Furui T., Mao M., Estrella V., Eder A., Pustilnik T., Sasagawa T., Lapushin R., Yu S., et al. 2000. Lysophospholipid growth factors in the initiation, progression, metastases, and management of ovarian cancer. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 905: 188–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu Y., Fang X. J., Casey G., Mills G. B. 1995. Lysophospholipids activate ovarian and breast cancer cells. Biochem. J. 309: 933–940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee J., Park S. Y., Lee E. K., Park C. G., Chung H. C., Rha S. Y., Kim Y. K., Bae G. U., Kim B. K., Han J. W., et al. 2006. Activation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha is necessary for lysophosphatidic acid-induced vascular endothelial growth factor expression. Clin. Cancer Res. 12: 6351–6358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Song Y., Wu J., Oyesanya R. A., Lee Z., Mukherjee A., Fang X. 2009. Sp-1 and c-Myc mediate lysophosphatidic acid-induced expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in ovarian cancer cells via a hypoxia-inducible factor-1-independent mechanism. Clin. Cancer Res. 15: 492–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Elabbadi N., Day C. P., Gamouh A., Zyad A., Yeaman S. J. 2005. Relationship between the inhibition of phosphatidic acid phosphohydrolase-1 by oleate and oleoyl-CoA ester and its apparent translocation. Biochimie. 87: 437–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.