Abstract

Due to its genetic tractability and increasing wealth of accessible data, the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae is a model system of choice for the study of the genetics, biochemistry, and cell biology of eukaryotic lipid metabolism. Glycerolipids (e.g., phospholipids and triacylglycerol) and their precursors are synthesized and metabolized by enzymes associated with the cytosol and membranous organelles, including endoplasmic reticulum, mitochondria, and lipid droplets. Genetic and biochemical analyses have revealed that glycerolipids play important roles in cell signaling, membrane trafficking, and anchoring of membrane proteins in addition to membrane structure. The expression of glycerolipid enzymes is controlled by a variety of conditions including growth stage and nutrient availability. Much of this regulation occurs at the transcriptional level and involves the Ino2–Ino4 activation complex and the Opi1 repressor, which interacts with Ino2 to attenuate transcriptional activation of UASINO-containing glycerolipid biosynthetic genes. Cellular levels of phosphatidic acid, precursor to all membrane phospholipids and the storage lipid triacylglycerol, regulates transcription of UASINO-containing genes by tethering Opi1 to the nuclear/endoplasmic reticulum membrane and controlling its translocation into the nucleus, a mechanism largely controlled by inositol availability. The transcriptional activator Zap1 controls the expression of some phospholipid synthesis genes in response to zinc availability. Regulatory mechanisms also include control of catalytic activity of glycerolipid enzymes by water-soluble precursors, products and lipids, and covalent modification of phosphorylation, while in vivo function of some enzymes is governed by their subcellular location. Genome-wide genetic analysis indicates coordinate regulation between glycerolipid metabolism and a broad spectrum of metabolic pathways.

THE yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, has emerged as a powerful model system for the elucidation of the metabolism, cell biology, and regulation of eukaryotic lipids. Due to the strong homology of yeast proteins, pathways, and regulatory networks with those in higher eukaryotes, yeast has provided numerous insights into the genetics and biochemistry of lipid-related diseases. As a system for the study of eukaryotic lipid metabolism, the advantages of yeast include its vast, well-curated, and electronically accessible archives of genetic data, including those detailing gene–enzyme relationships in the pathways for lipid synthesis and turnover. Another major advantage is the rapidly increasing understanding of the regulation and localization of enzymes and the movement of lipids within and among cellular membranes and compartments in yeast.

This article presents an overview of progress in elucidating gene–enzyme relationships, cellular localization, and regulatory mechanisms governing glycerolipid metabolism in yeast. The metabolism covered in this YeastBook chapter includes the regulation, synthesis, and turnover of phospholipids and triacylglycerol (TAG) and their precursors in the context of changing growth conditions and nutrient availability. All glycerophospholipids in yeast, including the major phospholipids, phosphatidylinositol (PI), phosphatidylserine (PS), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), and phosphatidylcholine (PC), are derived from the precursor lipid, phosphatidic acid (PA) (Figures 1 and 2). A major topic of this review article is the tremendous recent progress in elucidating the complex regulatory mechanisms that control the connected and coordinated pathways involved in the synthesis of glycerophospholipids and TAG, which is also derived from PA (Figures 2, 3, and 4). The regulation of glycerolipid metabolism occurs at many levels and is a major topic discussed in this article. Adding complexity to analysis of the regulatory networks connected to lipid metabolism is the fact that critical signals controlling this regulation arise during the ongoing biosynthesis and turnover of the lipids themselves and involve precursors and metabolites embedded in the metabolism.

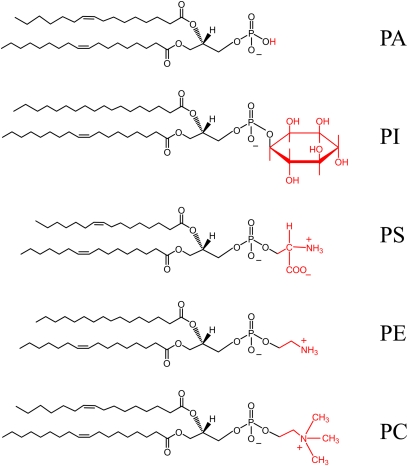

Figure 1 .

Phospholipid structures. The diagram shows the structures of the phospholipid PA and the major phospholipids PI, PS, PE, and PC that are derived from PA. The hydrophilic head groups (H, inositol, serine, ethanolamine, and choline) that are attached to the basic phospholipid structure are shown in red. The four most abundant fatty acids esterified to the glycerol-3-phosphate backbone of the phospholipids are palmitic acid, palmitoleic acid, steric acid, and oleic acid. The type and position of the fatty acyl moieties in the phospholipids are arbitrarily drawn. The relative amounts of the phospholipids as well as their fatty acyl compositions vary depending on strain (e.g., mutation) and growth condition.

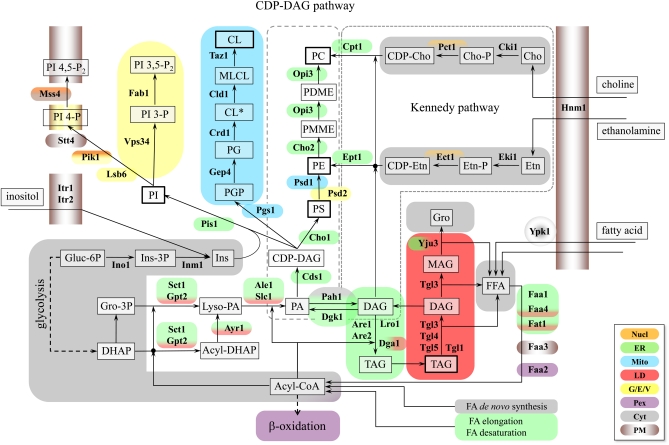

Figure 2 .

Pathways for the synthesis of glycerolipids and their subcellular localization. Phospholipids and TAG share DAG and PA as common precursors. In the de novo synthesis of phospholipids, PA serves as the immediate precursor of CDP-DAG, precursor to PI, PG, and PS. PS is decarboxylated to form PE, which undergoes three sequential methylations resulting in PC. PA also serves as a precursor for PGP, PG, and ultimately CL, which undergoes acyl-chain remodeling to the mature lipid. Alternatively, PA is dephosphorylated, producing DAG, which serves as the precursor of PE and PC in the Kennedy pathway. DAG also serves as the precursor for TAG and can be phosphorylated, regenerating PA. The names of the enzymes that are discussed in detail in this YeastBook chapter are shown adjacent to the arrows of the metabolic conversions in which they are involved and the gene–enzyme relationships are shown in Tables 1–3. Lipids and intermediates are boxed, with the most abundant lipid classes boxed in boldface type. Enzyme names are indicated in boldface type. The abbreviations used are: TAG, triacylglycerols; PI, phosphatidylinositol; PA, phosphatidic acid; CDP-DAG, CDP-diacylglycerol; DAG, diacylglycerol; MAG, monoacylglycerol; Gro, glycerol; DHAP, dihydroxyacetone phosphate, PS, phosphatidylserine; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine; PG, phosphatidylglycerol; PGP phosphatidylglycerol phosphate; CL* precursor cardiolipin; MLCL, monolyso-cardiolipin; CL, mature cardiolipin; PMME, phosphatidylmonomethylethanolamine; PDME, phosphatidyl-dimethylethanolamine; PC, phosphatidylcholine; FFA, free fatty acids; Cho, choline, Etn, ethanolamine, Ins, inositol; Cho-P, choline phosphate; CDP-Cho, CDP-choline; Etn-P, ethanolamine phosphate; CDP-Etn, CDP-ethanolamine; PI 3-P, phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate; PI 4-P, phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate; PI 4,5-P2, phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate; PI 3,5-P2, phosphatidylinositol 3,5-bisphosphate. Nucl, nucleus; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; Mito, mitochondria; LD, lipid droplets; G/E/V, Golgi, endosomes, vacuole; Pex, peroxisomes; Cyt, cytoplasma; PM, plasma membrane. CL* indicates a precursor of cardiolipin (CL) with saturated acyl-chain that undergoes deacylation/reacylation to mature CL. See text for details.

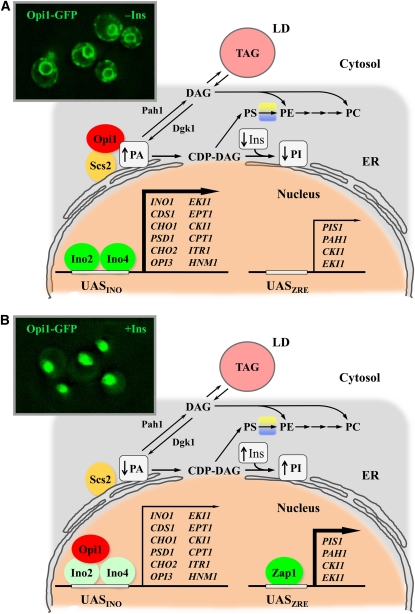

Figure 3 .

Model for PA-mediated regulation of phospholipid synthesis genes. (A) Growth conditions (e.g., exponential phase, inositol depletion, or zinc supplementation) under which the levels of PA are relatively high, the Opi1 repressor is tethered to the nuclear/ER membrane, and UASINO-containing genes are maximally expressed (boldface arrow) by the Ino2-Ino4 activator complex. (Inset) Localization of Opi1, fused with GFP at its C-terminal end and integrated into the chromosome, being expressed under its own promoter in live cells growing logarithmically in synthetic complete medium lacking inositol (−Ins) and analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. (B) Growth conditions (e.g., stationary phase, inositol supplementation, or zinc depletion) under which the levels of PA are reduced, Opi1 dissociates from the nuclear/ER membrane, and enters into the nucleus where it binds to Ino2 and attenuates (thin arrow) transcriptional activation by the Ino2–Ino4 complex. (Inset) Localization of Opi1, as described in A, except that the cells are growing logarithmically in medium containing 75 μM inositol. PA level decreases by the stimulation of PI synthesis in response to inositol (Ins) supplementation and by Zap1-mediated induction of PIS1, that results in an increase in PI synthesis in response to zinc depletion. The regulation in response to zinc depletion and stationary phase occurs without inositol supplementation. Pah1 and Dgk1 play important roles in controlling PA content and transcriptional regulation of UASINO-containing genes. The synthesis of TAG (which is stored in lipid droplets, LD) and phospholipids (with the exception of PE, which occurs in the mitochondria and Golgi) occurs in the ER. Fluorescence microscopy images of Opi1 localization courtesy of Yu-Fang Chang, Henry Laboratory, Department of Molecular Biology and Genetics, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY.

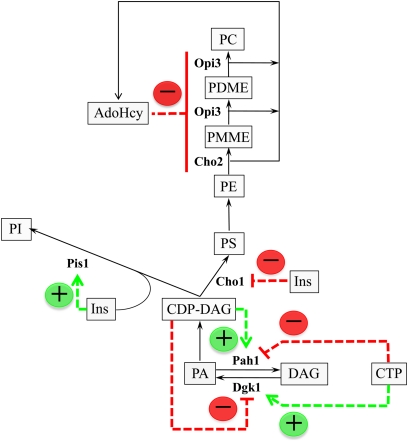

Figure 4 .

Regulation of phospholipid synthesis by soluble lipid precursors and metabolites. The diagram shows the major steps in the synthesis of phospholipids. The enzymes that are biochemically regulated by phospholipid precursors and products are shown. The green arrow designates the stimulation of enzyme activity, whereas the red line designates the inhibition of enzyme activity. Details on the biochemical regulation of these enzymes are discussed in the section Water soluble precursors of phospholipids, metabolism, and regulatory roles and in Carman and Han (2009a). See Figure 2 for abbreviations.

For example, PA plays a number of signaling roles vital to the regulation of lipid metabolism in yeast (Figure 3), in addition to its function as precursor to all phospholipids and TAG (Figure 2). PI synthesis is regulated in response to its precursor, inositol, on several levels (Figures 3 and 4) and PI also serves as precursor to both phosphatidylinositolphosphates and inositol-containing sphingolipids, both of which are implicated in a wide range of signaling and regulatory activities (Strahl and Thorner 2007; Dickson 2008, 2010), topics that will not be dealt with in detail in this YeastBook chapter. In addition, the enzymes controlling the metabolism of gycerolipids are localized to specific cellular compartments (Figure 2; Tables 1–3), while the lipids themselves are, for the most part, distributed to a much wider range of cellular compartments. Moreover, the regulation of TAG metabolism plays a major role in lipid droplet (LD) formation and depletion (Murphy and Vance 1999; Rajakumari et al. 2008; Kurat et al. 2009; Kohlwein 2010a), a topic that will also be addressed in detail in the chapter on Lipid Droplets and Peroxisomes. Thus, detailed knowledge of pathways, gene–enzyme relationships, and subcellular localization of enzymes and pools of lipids and metabolites involved in the synthesis and turnover of glycerolipids (Figures 2–4, Tables 1–3) is essential to the elucidation of the complex mechanisms responsible for their regulation.

Table 1 . Glycerolipid synthesis enzymes.

| Gene | Ino− or Opi− phenotype | Enzyme | Mol mass (kDa) | Isoelectric point | Molecules per cellb | Locationc | Transmembrane domains | Phosphorylation sitesd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCT1 (GAT2) | Ino− | Glycerol-3-P /dihydroxyacetone-P acyltransferase | 85.7 | 7.27 | 1050 | ER | 4 | Few |

| GPT2 (GAT1) | — | Glycerol-3-P /dihydroxyacetone-P acyltransferase | 83.6 | 10.3 | 3100 | ER, lipid droplets | 4 | Several |

| AYR1 | — | Acyl DHAP reductase | 32.8 | 9.92 | 3670 | ER, lipid droplets | None | None |

| SLC1 | — | LysoPA/Acylglycerol-3-P acyltransferase | 33.8 | 10.41 | ND | ER, lipid droplets | 1 | None |

| ALE1 (SLC4,LPT1,LCA1) | — | LysoPA/Acylglycerol-3-P acyltransferase | 72.2 | 10.3 | ND | ER | 7 | Several |

| PSI1 (CST26) | — | LysoPI acyltransferase | 45.5 | 10.15 | 2010 | ER | 4 | None |

| TAZ1 | — | LysoPC acyltransferase/ monolysoCL acyltransferase | 44.2 | 9.38 | 1340 | Mitochondria | None | None |

| CDS1 (CDG1)a | Opi− | CDP-DAG synthase | 51.8 | 8.64 | ND | ER, mitochondria | 6 | Few |

| CHO1 (PSS1)a | Opi− | PS synthase | 30.8 | 6.23 | ND | ER | 2 | Several |

| PSD1a | Opi− | PS decarboxylase | 56.6 | 9.84 | 1080 | Mitochondria | None | None |

| PSD2 | — | PS decarboxylase | 130 | 7.85 | ND | Vacuole, endomembranes | None | Few |

| CHO2 (PEM1)a | Opi− | PE methyltransferase | 101.2 | 8.56 | 1810 | ER | 8 | Few |

| OPI3 (PEM2)a | Opi− | Phospholipid methyltransferase | 23.1 | 9.6 | 5890 | ER, mitochondria | None | None |

| PAH1 (SMP2) | — | PA phosphatase | 95 | 4.68 | 3910 | Cytoplasm, ER | None | Several |

| DGK1 (HSD1) | — | DAG kinase | 32.8 | 9.48 | 784 | ER | 4 | Few |

| EKI1a | — | Ethanolamine kinase | 61.6 | 5.69 | 3420 | Cytoplasm | None | Few |

| ECT1 (MUQ1) | — | Ethanolamine-P cytidylyltransferase | 36.8 | 6.44 | 4700 | Cytoplasm | None | None |

| EPT1a | — | Ethanolamine/choline phosphotransferase | 44.5 | 6.5 | ND | ER | 7 | None |

| CKI1a | — | Choline kinase | 66.3 | 5.43 | 3930 | Cytoplasm | None | Several |

| PCT1 (CCT1,BSR2)a | Opi− | Choline-P cytidylyltransferase | 49.4 | 9.26 | 3050 | Cytoplasm, nucleus | None | Several |

| CPT1a | — | Choline phosphotransferase | 44.8 | 6.57 | 981 | Membrane | 8 | None |

| PGS1 (PEL1) | — | PGP synthase | 59.3 | 10.5 | ND | Mitochondria | None | None |

| GEP4 | — | PGP phosphatase | 20.9 | 9.18 | ND | Mitochondria | None | None |

| CRD1 (CLS1) | — | CL synthase | 32 | 10.55 | 876 | Mitochondria | 3 | None |

| PIS1 | Ino− | PI synthase | 24.8 | 8.92 | 3810 | ER | 3 | None |

| LSB6 | — | PI 4-kinase | 70.2 | 6.68 | 57 | Plasma membrane, vacuole membrane | None | None |

| STT4 | Ino− | PI 4-kinase | 214.6 | 7.44 | 846 | Plasma membrane | None | Few |

| PIK1 | — | PI 4-kinase | 119.9 | 6.46 | 1600 | Plasma membrane, nucleus, Golgi | None | Several |

| VPS34 (END12,PEP15,VPL7,VPT29,STT8,VPS7) | Opi− | PI 3-kinase | 100.9 | 7.79 | 1080 | Vacuole | None | None |

| MSS4 | Ino− | PI 4-P 5-kinase | 89.3 | 10.13 | ND | Cytoplasm | None | Several |

| FAB1 (SVL7) | Ino− | PI 3-P 5-kinase | 257.4 | 8.45 | 149 | Vacuole | None | Several |

| DGA1a | — | Acyl-CoA diacylglycerol acyltransferase | 47.7 | 10.39 | 907 | ER, lipid droplets | 1 | Few |

| LRO1a | — | Phospholipid diacylglycerol acyltransferase | 75.3 | 6.67 | ND | ER | 1 | Few |

| ARE1 (SAT2)a | — | Acyl-CoA sterol acyltransferase | 71.6 | 8.27 | ND | ER | 9 | Several |

| ARE2 (SAT1)a | — | Acyl-CoA sterol acyltransferase | 74.0 | 7.71 | 279 | ER | 9 | Several |

| Phospholipid synthesis regulatory proteins | ||||||||

| INO2 (DIE1, SCS1)a | Ino− | Transcriptional activator | 34.2 | 6.23 | 784 | Nucleus | None | None |

| INO4 | Ino− | Transcriptional activator | 17.4 | 10.21 | 521 | Nucleus, cytoplasm | None | None |

| OPI1 | Opi− | Transcriptional repressor | 46 | 4.87 | 1280 | Nuclear/ER membrane | None | Few |

Much of the information in the table may be found in the Saccharomyces Genome Database. Ino−, inositol auxotrophy; Opi−, inositol excretion; ND, not determined.

Genes containing the UASINO element and regulated by the Ino2-Ino4-Opi1 circuit. The names in parentheses are aliases.

Table 3 . Glycerolipid turnover enzymes.

| Gene | Ino− or Opi−phenotype | Enzyme | Mol mass (kDa) | Isoelectric point | Molecules per cella | Locationbb | Transmembrane domains | Phosphorylation sitesc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLD1 | — | CL specific phospholipase A2 | 52 | 10.3 | ND | Mitochondria | None | None |

| NTE1 | Ino− | PC specific phospholipase B | 187.1 | 8.19 | 521 | ER | 3 | Several |

| PLB1 | — | PC/PE specific phospholipase B | 71.6 | 4.36 | ND | Plasma membrane, ER, vesicles, extracellular | None | None |

| PLB2 | — | Nonspecific phospholipase B | 75.4 | 4.35 | 623 | Plasma membrane, ER, vesicles | None | None |

| PLB3 | — | Nonspecific phospholipase B | 75 | 4.7 | ND | Cytoplasm, vacuole, vesicles | None | None |

| PLC1 | — | PI 4,5-P2 specific phospholipase C | 110.5 | 9.84 | ND | Cytoplasm | None | Few |

| PGC1 | — | PG specific phospholipase C | 37 | 8.93 | 3270 | Mitochondria | None | None |

| SPO14 (PLD1) | — | PC specific phospholipase D | 195.2 | 7.58 | 49 | Cytoplasm | None | Several |

| SAC1 (RSD1) | Ino− | Nonspecific polyphosphoinositide phosphatase | 71.1 | 7.75 | 48,000 | ER, Golgi, vacuole | 2 | None |

| INP51 (SJL1) | — | PI 4,5-P2 phosphatase | 108.4 | 6.7 | 98 | Cytoplasm | None | None |

| INP52 (SJL2) | — | Nonspecific polyphosphoinositide phosphatase | 133.3 | 8.97 | ND | Actin | None | Several |

| INP53 (SJL3, SOP2) | — | Nonspecific polyphosphoinositide phosphatase | 124.6 | 7.18 | 1520 | Actin | None | Several |

| INP54 | — | PI 4,5-P2 phosphatase | 43.8 | 7.6 | 1200 | ER | None | None |

| YRM1 | — | PI 3-P phosphatase | 91 | 7.19 | 125 | Cytoplasm | None | Few |

| FIG4 | — | PI 3,5-P2 phosphatase | 101.7 | 5.52 | 339 | Vacuole | None | None |

| DPP1 (ZRG1) | — | DGPP phosphatase/nonspecific lipid phosphate phosphatase | 33.5 | 6.42 | 3040 | Vacuole | 5 | Few |

| LPP1 | — | Nonspecific lipid phosphate phosphatase | 31.5 | 8.25 | 300 | Golgi | 4 | None |

| PHM8 | — | LysoPA phosphatase | 37.7 | 5.14 | 195 | Cytoplasm, nucleus | None | None |

| TGL1 | — | Triacylglycerol lipase, sterylester hydrolase | 63.0 | 6.83 | 1470 | ER, lipid droplets | None | Several |

| TGL2 | — | Acylglycerol lipase | 37.5 | 8.41 | ND | Mitochondria | None | None |

| TGL3 | — | Triacylglycerol lipase, lysoPA acyltransferase | 73.6 | 8.50 | 3210 | Lipid droplets | 1 | Few |

| TGL4 | — | Triacylglycerol lipase, Ca++ dependent phospholipase A2, lysoPA acyltransferase | 102.7 | 8.05 | 195 | Lipid droplets | None | Several |

| TGL5 | — | Triacylglycerol lipase, lysoPA acyltransferase | 84.7 | 9.84 | 358 | Lipid droplets | 1 | Several |

| YJU3 | — | Monoacylglycerol lipase | 35.6 | 8.5 | 2140 | Lipid droplet, ER | None | None |

Much of the information in the table may be found in the Saccharomyces Genome Database. The names in parentheses are aliases. Ino−, inositol auxotrophy; ND, not determined.

Notably, in eukaryotes phospholipids play many vital roles in the biology of the cell that extend beyond lipid metabolism itself. These include roles in membrane trafficking and membrane identity (Vicinanza et al. 2008) and anchoring of membrane proteins (Roth et al. 2006; Pittet and Conzelmann 2007; Fujita and Jigami 2008), complex topics in their own right, which will be discussed only in brief in this YeastBook chapter. Phospholipids also serve as signaling molecules and as precursors of signaling molecules (Strahl and Thorner 2007). Thus, the advancements in yeast glycerolipid metabolism discussed in this review article also have enormous potential to contribute critical insights into these vital roles of lipids and lipid-mediated signaling in eukaryotic cells.

Pathways of glycerolipid metabolism

Major glycerolipids of S. cerevisiae include the phospholipids PC, PE, PI, PS (Figure 1), phosphatidylglycerol (PG), and cardiolipin (CL) (Rattray et al. 1975; Henry 1982; Carman and Henry 1989; Paltauf et al. 1992; Guan and Wenk 2006; Ejsing et al. 2009). Minor phospholipids include intermediates such as PA, CDP-diacylglycerol (CDP-DAG), phosphatidylmonomethylethanolamine (PMME), phosphatidyldimethylethanolamine (PDME), the D-3, D-4, and D-5 polyphosphoinositides, and lysophospholipids (Rattray et al. 1975; Oshiro et al. 2003; Strahl and Thorner 2007). TAG and diacylglycerol (DAG) are the major neutral glycerolipids. The fatty acids that are commonly esterified to the glycerophosphate backbone of yeast glycerolipids include palmitic acid (C16:0), palmitoleic acid (C16:1), stearic acid (C18:0), and oleic acid (C18:1) (Rattray et al. 1975; Henry 1982; Bossie and Martin 1989; McDonough et al. 1992; Martin et al. 2007). The pathways for the synthesis of phospholipids and TAG are shown in Figure 2. The enzymes and transporters of glycerolipid metabolism and the genes that encode them are listed in Tables 1–3. The gene–protein relationships shown in the tables have been confirmed by the analysis of gene mutations and/or by the biochemical characterization of the enzymes and transporters (Carman and Henry 1989; Greenberg and Lopes 1996; Henry and Patton-Vogt 1998; Carman and Henry 1999; Black and Dirusso 2007; Tehlivets et al. 2007; Kohlwein 2010b; Carman and Han 2011).

Synthesis and turnover of phospholipids

In the de novo pathways (Figure 2, Table 1), all membrane phospholipids are synthesized from PA, which is derived from glycerol-3-P via lysoPA by two fatty acyl CoA-dependent reactions that are catalyzed in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) by the SCT1- and GPT2-encoded glycerol-3-P acyltransferases and the SLC1- and ALE1-encoded lysoPA/lysophospholipid acyltransferases, respectively (Athenstaedt and Daum 1997; Athenstaedt et al. 1999b; Zheng and Zou 2001; Benghezal et al. 2007; Chen et al. 2007b; Jain et al. 2007; Riekhof et al. 2007b). The glycerol-3-P acyltransferase enzymes also utilize dihydroxyacetone-P as a substrate, and the product acyl dihydroxyacetone-P is converted to lysoPA by the lipid droplet (LD) and ER-associated AYR1-encoded reductase (Athenstaedt and Daum 2000). At this point in the pathway, PA is partitioned to CDP-DAG, catalyzed by CDS1-encoded CDP-DAG synthase (Carter and Kennedy 1966; Kelley and Carman 1987; Shen et al. 1996) or to DAG, catalyzed by PAH1-encoded PA phosphatase (Han et al. 2006) (Figure 1). CDP-DAG synthase activity has been detected in the ER and in mitochondria (Kuchler et al. 1986), whereas PA phosphatase is a cytosolic enzyme that must associate with membranes to catalyze the dephosphorylation of PA to produce DAG (Han et al. 2006; Carman and Han 2009a). CDP-DAG and DAG are used to synthesize PE and PC by two alternative routes, namely, the CDP-DAG and Kennedy pathways (Figure 2). In the CDP-DAG pathway, CDP-DAG is converted to PS by the ER localized CHO1-encoded PS synthase (Atkinson et al. 1980; Letts et al. 1983; Bae-Lee and Carman 1984; Kiyono et al. 1987; Nikawa et al. 1987b). Yeast has two PS decarboxylases encoded, by the PSD1 and PSD2 genes. Psd1, localized to the inner mitochondrial membrane, accounts for the majority of the enzymatic activity in yeast, while the minor activity, Psd2, associates with Golgi/vacuole (Clancey et al. 1993; Trotter et al. 1993, 1995; Voelker 2003). PE then undergoes three sequential methylation reactions in the ER (Gaynor and Carman 1990), the first of which is catalyzed by the CHO2-encoded PE methyltransferase, while the final two methylations are catalyzed by the OPI3-encoded phospholipid methyltransferase (Kodaki and Yamashita 1987; Summers et al. 1988; Kodaki and Yamashita 1989; McGraw and Henry 1989). The CDP-DAG pathway is the major route for synthesis of PE and PC when wild-type cells are grown in the absence of ethanolamine and choline, and cho1, psd1psd2, and cho2opi3 mutants defective in this pathway have choline/ethanolamine auxotrophy phenotypes (Atkinson et al. 1980a Summers et al. 1988; McGraw and Henry 1989; Trotter and Voelker 1995; Trotter et al. 1995). PE and PC synthesis in mutants defective in the CDP-DAG pathway can also be supported by exogenously supplied lysoPE, lysoPC, or PC with short acyl chains, which are transported into the cell. LysoPE and lysoPC are acylated by the ALE1-encoded lysophospholipid acyltransferase (Jain et al. 2007; Tamaki et al. 2007; Riekhof et al. 2007a,b). Short chain PE and PC are remodeled with C16 and C18 acyl chains prior to incorporation into the membrane (Tanaka et al. 2008; Deng et al. 2010).

In the Kennedy pathway (Hjelmstad and Bell 1990), PE and PC are synthesized, respectively, from ethanolamine and choline (Figure 2, Table1). Exogenous ethanolamine and choline are both transported into the cell by the HNM1-encoded choline/ethanolamine transporter (Nikawa et al. 1986). The EKI1-encoded ethanolamine kinase (Kim et al. 1999) and the CKI1-encoded choline kinase (Hosaka et al. 1989) are both cytosolic enzymes, which, respectively, phosphorylate ethanolamine and choline with ATP to form ethanolamine-P and choline-P. Ethanolamine-P may also be derived from sphingolipids by dihydrosphingosine-1-P lyase, encoded by the DPL1 gene (Saba et al. 1997; Schuiki et al. 2010). These intermediates are then activated with CTP to form CDP-ethanolamine and CDP-choline, respectively, by the ECT1-encoded ethanolamine-P cytidylyltransferase (Min-Seok et al. 1996) and the PCT1-encoded choline-P cytidylyltransferase (Tsukagoshi et al. 1987), which are associated with the nuclear/ER membrane (Huh et al. 2003; Natter et al. 2005). Finally, the EPT1-encoded ethanolamine phosphotransferase (Hjelmstad and Bell 1988, 1991) and the CPT1-encoded choline phosphotransferase (Hjelmstad and Bell 1987, 1990), respectively, catalyze the reactions of CDP-ethanolamine and CDP-choline with DAG provided by the PAH1-encoded PA phosphatase to form PE and PC. Ept1 will also catalyze the CDP-choline–dependent reaction (Hjelmstad and Bell 1988). Cpt1 and Ept1 have somewhat ambiguous patterns of localization to vesicular structures, but have also been described to localize to mitochondria or ER (Huh et al. 2003; Natter et al. 2005).

The CDP-DAG and Kennedy pathways are both used by wild-type cells, regardless of whether or not ethanolamine and choline are present in the growth medium (Patton-Vogt et al. 1997; Henry and Patton-Vogt 1998; Kim et al. 1999). In the absence of exogenous choline, this Kennedy pathway precursor may be derived from hydrolysis of PC synthesized by the CDP-DAG pathway and subsequently hydrolyzed by phospholipase D (Patton-Vogt et al. 1997; Xie et al. 1998) encoded by the SPO14 gene (Rose et al. 1995; Waksman et al. 1996). Choline for PC synthesis can also be derived from Nte1-catalyzed deacylation (Zaccheo et al. 2004) followed by hydrolysis by Gde1 to produce choline and glycerophosphate (Fernandez-Murray and McMaster 2005a; Fisher et al. 2005; Patton-Vogt 2007). The activity of a Ca++-dependent phospholipase D with preference for PS and PE has been detected (Mayr et al. 1996), but the corresponding gene encoding a PE-specific phospholipase D has yet to be identified. Thus, proof that ethanolamine derived from PE is recycled for PE synthesis via the Kennedy pathway is still lacking. Kennedy pathway mutants (e.g., cki1eki1 and cpt1ept1) defective in both the CDP-choline and CDP-ethanolamine branches can synthesize PC only by the CDP-DAG pathway (McMaster and Bell 1994; Morash et al. 1994; Kim et al. 1999). However, unlike the CDP-DAG pathway mutants, the Kennedy pathway mutants do not exhibit any auxotrophic requirements and have an essentially normal complement of phospholipids (Morash et al. 1994; Kim et al. 1999).

In the synthesis of the inositol-containing phospholipids (Figure 2, Table 1), CDP-DAG donates its phosphatidyl moiety to inositol to form PI (Paulus and Kennedy 1960; Fischl and Carman 1983) in a reaction that competes in the ER with PS synthase for their common substrate, CDP-DAG (Kelley et al. 1988). While PIS1-encoded PI synthase is essential, a strain expressing a mutant form of Pis1 with a lower affinity for inositol has been isolated as an inositol auxotroph (Nikawa and Yamashita 1984; Nikawa et al. 1987a). The inositol used in PI synthesis is either synthesized de novo (discussed below) or obtained from the growth medium via the ITR1- and ITR2-encoded inositol transporters (Table 2) (Nikawa et al. 1991). Once formed, PI may be converted to PI 3-P by the VPS34-encoded PI 3 kinase (Herman and Emr 1990; Schu et al. 1993) or to PI 4-P by the PI 4 kinases encoded by LSB6 (Han G-S et al. 2002; Shelton et al. 2003), STT4 (Yoshida et al. 1994a), and PIK1 (Flanagan et al. 1993; Garcia-Bustos et al. 1994). PI 4-P may be further phosphorylated to PI 4,5-P2 by the MSS4-encoded PI 4-P 5 kinase (Yoshida et al. 1994b), whereas PI 3-P may be phosphorylated to PI 3,5-P2 by the FAB1-encoded PI 3-P 5 kinase (Yamamoto et al. 1995). The specific localization of these kinases and the lipids they produce play important roles in signaling, membrane identity, and membrane trafficking (Strahl and Thorner 2007). PI also serves as a precursor in the synthesis of the complex sphingolipids in yeast, which also play essential roles in signaling and membrane function (Dickson and Lester 2002; Dickson 2008), topics that are beyond the scope of this YeastBook chapter.

Table 2 . Glycerolipid precursor enzymes and transporters.

| Gene | Ino− or Opi− phenotype | Enzyme | Mol mass (kDa) | Isoelectric point | Molecules per cellb | Locationc | Transmembrane domains | Phosphorylation sitesd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACC1 (ABP2,FAS3,MTR7)a | — | Acetyl CoA carboxylase | 250.4 | 6.22 | 20,200 | Cytoplasm | None | Several |

| HFA1 | — | Acetyl CoA carboxylase | 241.8 | 8.05 | 396 | Mitochondria | None | Few |

| FAS1a | — | Fatty acid synthase (β subunit) | 228.7 | 5.79 | 91,800 | Cytoplasm | None | Several |

| FAS2a | — | Fatty acid synthase (α subunit) | 206.9 | 5.21 | 17,000 | Cytoplasm | None | Several |

| ETR1(MRF’) | Ino− | 2-Enoyl thioester reductase | 42 | 9.78 | 1560 | Mitochondria | None | None |

| HTD2 (RMD12) | — | 3-Hydroxyacyl-thioester dehydratase | 33 | 9 | 799 | Mitochondria | None | None |

| MCT1 | — | Malonyl-CoA:ACP transferase | 40.7 | 6.9 | 1360 | Mitochondria | None | None |

| OAR1 | — | 3-Oxoacyl-ACP reductase | 31.2 | 9.3 | 1760 | Mitochondria | None | None |

| ACP1 | — | Acyl carrier protein | 13.9 | 4.64 | 60,500 | Mitochondria | None | Few |

| PPT2 | — | Phosphopantetheine:protein transferase | 19.9 | 8.46 | 486 | Mitochondria | None | None |

| CEM1 | — | β-keto-acyl synthase | 47.6 | 8.26 | 1660 | Mitochondria | None | None |

| FAA1 | — | Fatty acyl CoA synthetase | 77.8 | 7.58 | 7470 | ER, lipid droplets | None | None |

| FAA2 (FAM1) | — | Fatty acyl CoA synthetase | 83.4 | 7.7 | 358 | Peroxisomes | None | None |

| FAA3 | — | Fatty acyl CoA synthetase | 77.9 | 9.7 | 6440 | Plasma membrane | None | None |

| FAA4 | — | Fatty acyl CoA synthetase | 77.2 | 6.52 | 31,200 | ER, lipid droplets | None | None |

| FAT1 | — | Fatty acid transporter and fatty acyl CoA synthetase | 77.1 | 8.47 | 16,900 | ER, lipid droplets | 3 | None |

| OLE1 (MDM2) | — | Δ9 Fatty acid desaturase | 58.4 | 9.71 | ND | ER | 4 | None |

| ELO1 | — | FA elongase, condensing enzyme | 36.2 | 10.2 | 937 | ER | 5 | None |

| FEN1 (ELO2) | — | FA elongase, condensing enzyme | 40.0 | 10.35 | 3510 | ER | 7 | Several |

| SUR4 (ELO3) | — | FA elongase, condensing enzyme | 39.5 | 10.13 | ND | ER | 6 | None |

| IFA38 (YBR159w) | — | β-keto acyl-CoA reductase | 38.7 | 10.28 | 41900 | ER | 1 | None |

| PHS1 | — | 3-Hydroxy acyl-CoA dehydratase | 24.5 | 10.84 | ND | ER | 6 | None |

| TSC13 | — | Enoyl-CoA reductase | 36.8 | 10.38 | 23600 | ER | 4 | None |

| INO1a (APR1) | Ino− | Inositol 3-P synthase | 59.6 | 5.77 | ND | Cytoplasm | None | None |

| INM1 | — | Inositol 3-P phosphatase | 32.8 | 5 | 2440 | Cytoplasm, nucleus | None | None |

| URA7 | Ino− | CTP synthetase | 64.7 | 5.93 | 57,600 | Cytoplasm | None | Several |

| URA8 | — | CTP synthetase | 63 | 6.02 | 5370 | Cytoplasm | None | None |

| ITR1a | Opi− | Inositol transporter | 63.5 | 6.51 | ND | Plasma membrane | 12 | Several |

| ITR2 (HRB612) | — | Inositol transporter | 66.7 | 8.25 | 468 | Plasma membrane | 12 | None |

| HNM1 (CTR1)a | — | Choline transporter | 62 | 6.83 | ND | Plasma membrane | 12 | Few |

| GIT1 | — | GroPIns/GroPCho transporter | 57.3 | 8.64 | ND | Plasma membrane | 11 | None |

Much of the information in the table may be found in the Saccharomyces Genome Database. Ino−, inositol auxotrophy; Opi−, inositol excretion; ND, not determined.

Genes containing the UASINO element and are regulated by the Ino2-Ino4-Opi1 circuit, The names in parentheses are aliases.

In the synthesis of mitochondrial-specific phospholipids (Figure 2, Table1), CDP-DAG donates its phosphatidyl moiety to glycerol-3-P to form phosphatidylglycerophosphate (PGP) in the reaction catalyzed by the PGS1-encoded PGP synthase (Janitor and Subik 1993; Chang et al. 1998a). PGP is then dephosphorylated to PG by the GEP4-encoded PGP phosphatase (Osman et al. 2010). The CRD1-encoded CL synthase (Jiang et al. 1997; Chang et al. 1998b; Tuller et al. 1998) catalyzes the reaction between PG and another molecule of CDP-DAG to generate CL. The CLD1-encoded cardiolipin-specific phospholipase and the TAZ1-encoded monolyso cardiolipin acyltransferase, involved in establishing specific unsaturated cardiolipin species, are also specifically associated with the mitochondria (Beranek et al. 2009; Brandner et al. 2005).

The enzymes that catalyze the turnover of phospholipids include both phospholipases and lipid phosphatases (Table 3). NTE1-encoded phospholipase B (Zaccheo et al. 2004; Fernandez-Murray and McMaster 2005b, 2007) is an integral ER membrane protein and removes both fatty acids from PC to produce glycerophosphocholine (GroPCho). GroPCho may be re-acylated by an uncharacterized acyltransferase to PC (Ståhlberg et al. 2008). The phospholipase B enzymes encoded by PLB1, PLB2, and PLB3 catalyze the same type of reaction, but they are not specific and their localization is ambiguous. Plb1 localizes to the ER, vesicles, the plasma membrane, and the extracellular space and primarily utilizes PC and PE as substrates, whereas Plb3 is found in vesicles, vacuoles, as well as the cytosol and primarily uses PI as a substrate (Lee et al. 1994; Fyrst et al. 1999; Merkel et al. 1999, 2005). The GroPCho and glycerophosphoinositol (GroPIns) produced by the phospholipase B enzymes may be excreted into the growth medium and then transported back into the cell by the GIT1-encoded GroPCho/GroPIns transporter localized in the plasma membrane (Patton-Vogt and Henry 1998; Fisher et al. 2005). In turn, these molecules are hydrolyzed by a phosphodiesterase to produce the phospholipid precursor molecules choline and inositol, respectively (Patton-Vogt 2007). PLC1-encoded phospholipase C is cytosolic and specific for PI 4,5-P2 and produces DAG and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (Flick and Thorner 1993; Yoko-O et al. 1993), and the PGC1-encoded phospholipase C localizes to lipid droplets and mitochondria and is specific for PG and produces DAG and glycerol 3-P (Simockova et al. 2008). The SPO14-encoded cytosolic phospholipase D is specific for PC and produces PA and choline (Rose et al. 1995; Waksman et al. 1996). Most phospholipids undergo rapid turnover and acyl-chain remodeling, which yields the typical complex pattern of lipid molecular species found in yeast (Schneiter et al. 1999; Guan and Wenk 2006; Ejsing et al. 2009). This remodeling is governed by specific acyltransferases, such as the PSI1-encoded acyltransferase in the ER that is involved in stearoyl-acylation of PI (Le Guedard et al. 2009), or the CLD1-encoded cardiolipin-specific phospholipase A in mitochondria (Beranek et al. 2009) and the TAZ1-encoded acyltransferase (yeast tafazzin ortholog; Gu et al. 2004; Testet et al. 2005). Moreover, several enzymes of TAG synthesis and degradation have additional activities, suggesting that they also may play a role in phospholipid acyl-chain remodeling (Rajakumari et al. 2008; Kohlwein 2010b; Rajakumari and Daum 2010a,b).

There are several phosphatase enzymes that catalyze the dephosphorylation of the polyphosphoinositides. Some of these enzymes are specific and some have broad substrate specificity. The YMR1-encoded (Taylor et al. 2000) and FIG4-encoded (Gary et al. 2002) phosphatases are specific for PI 3-P and PI 3,5-P2, respectively, whereas INP51-encoded (Stolz et al. 1998b) and INP54-encoded (Wiradjaja et al. 2001) phosphatases are specific for PI 4,5-P2. The phosphatase encoded by SAC1 will utilize PI 3-P, PI 4-P, and PI 3,5-P2 (Guo et al. 1999), whereas the phosphatases encoded by INP52 and INP53 will utilize any polyphosphoinositide as a substrate (Stolz et al. 1998; Guo et al. 1999).

The DPP1- and LPP1-encoded lipid phosphate phosphatase enzymes dephosphorylate a broad spectrum of substrates that include DAG pyrophosphate (DGPP), PA, lysoPA, sphingoid-base phosphates, and isoprenoid phosphates (Toke et al. 1998, 1999; Faulkner et al. 1999). While these enzymes may utilize PA as a substrate, they are not involved in the de novo synthesis of phospholipids and TAG; the function of which is ascribed to the PAH1-encoded PA phosphatase (Han et al. 2006; Carman and Han 2009a). The PHM8 gene encodes a lipid phosphatase that is specific for lysoPA and yields monoacylglycerol (MAG) and Pi (Reddy et al. 2008). N-acyl PE is a minor phospholipid species implicated in signaling processes (Merkel et al. 2005) and is degraded by the FMP30-encoded phospholipase D to N-acylethanolamide (NAE), which is related to endocannabinoids (Muccioli et al. 2009). NAE may be catabolized by Yju3, the major MAG lipase in yeast (see below).

Synthesis and turnover of TAG

The pathways for the synthesis of TAG and phospholipids share the same initial steps (Figure 2; Table 1; Kohlwein 2010b). Indeed, TAG is derived from the phospholipid, PA. The PAH1-encoded PA phosphatase provides DAG, which is acylated by the DGA1- and LRO1-encoded acyl-CoA–dependent and phospholipid-dependent diacylglycerol acyltransferases, respectively, to TAG (Oelkers et al. 2000; Oelkers et al. 2002; Sorger and Daum 2002; Kohlwein 2010b). The ARE1- and ARE2-encoded sterol acyltransferases utilize acyl-CoA but contribute only marginally to TAG synthesis from DAG (Yang, H. et al. 1996). Notably, deletion of both DGA1 and LRO1 genes does not result in a readily detectable growth phenotype in wild-type cells, indicating that TAG synthesis is not essential (Oelkers et al. 2002; Sorger and Daum 2002). Similarly, simultaneous deletion of the ARE1 and ARE2 genes does not impair cell growth (Yang et al. 1996). Even the dga1Δlro1Δare1Δare2Δ quadruple mutant that lacks both TAG and steryl esters, and has no lipid droplets (LD), exhibits only a slight extension of the lag phase after recovery from quiescence (Petschnigg et al. 2009). The dga1Δlro1Δare1Δare2Δ quadruple mutant, however, does exhibit a defect in sterol synthesis (Sorger et al. 2004) and is highly sensitive to unsaturated fatty acid (FA) supplementation (Garbarino et al. 2009; Petschnigg et al. 2009). Strikingly, provision of exogenous unsaturated FA in the absence of TAG synthesis leads to respiration-dependent cell necrosis (Rockenfeller et al. 2010), challenging the dogma that lipid-induced cell death is exclusively apoptotic. The dga1Δlro1Δare1Δare2Δ quadruple mutant also displays an Ino– phenotype at elevated growth temperature, indicative of altered INO1 expression and/or defective PI synthesis (Gaspar et al. 2011), ER stress induced by tunicamycin, which inhibits protein glycosylation and stimulates LD formation in wild-type cells. However, the dga1Δlro1Δare1Δare2Δ quadruple mutant is no more sensitive to tunicamycin than wild type, indicating that LD formation is not protective against this form of stress (Fei et al. 2009). Dga1 and Lro1 acyltransferase-dependent TAG synthesis, on the other hand, is required for growth at semipermissive temperatures in the absence of inositol in the sec13ts-1 mutant, defective in COPII vesicle budding from the ER. When shifted to higher growth temperature, the sec13ts mutant channels PA and DAG precursors from phospholipid into TAG, which apparently provides a degree of protection from the secretory stress caused by a block in membrane trafficking (Gaspar et al. 2008).

TAG hydrolysis (Figure 2, Table 3) clearly contributes lipid precursors that are essential to the resumption of growth upon exit from stationary phase (Kurat et al. 2009; Kohlwein 2010b). TAG degradation provides substrates for the synthesis of phospholipids and sphingolipids (Rajakumari et al. 2010), which are required for efficient cell cycle progression upon exit from quiescence (Kurat et al. 2009). Degradation of TAG is catalyzed by TGL1-, TGL3-, TGL4-, and TGL5-encoded TAG lipases, all of which are localized to LD (Athenstaedt and Daum 2003, 2005; Jandrositz et al. 2005; Kurat et al. 2006; Rajakumari et al. 2008; Kurat et al. 2009; Kohlwein, 2010b). Tgl1 harbors the canonical lipase catalytic triad, consisting of serine201, aspartate369 and histidine396 (Jandrositz et al. 2005). In contrast, Tgl3, Tgl4, and Tgl5 (and also Nte1, see above) are members of the patatin domain-containing family of (phospho) lipases, characterized by a catalytic diad of serine and aspartate (Kurat et al. 2006). The substrate specificities of the Tgl3, Tgl4, and Tgl5 TAG lipases differ. Tgl5 preferentially hydrolyses TAG molecular species harboring very long chain fatty acids (VLCFA) (Athenstaedt and Daum 2005), while Tgl3 also accepts DAG as a substrate in addition to TAG (Kurat et al. 2006). Tgl3, Tgl4, and Tgl5 also possess lysoPA acyltransferase activities, and Tgl4 additionally functions as a Ca++-dependent phospholipase A2 and steryl ester hydrolase (Rajakumari and Daum 2010a,b). Although Tgl1 also contributes to TAG hydrolysis, its major activity is as a steryl ester hydrolase, in conjunction with the YEH1- and YEH2-encoded enzymes (Jandrositz et al. 2005; Koffel et al. 2005). TGL2 encodes an acylglycerol lipase localized to mitochondria, but its role in TAG homeostasis has not been clarified yet (Ham et al. 2010). YJU3 encodes the major monoacylglycerol (MAG) lipase in yeast (Heier et al. 2010), but yju3Δ mutants do not display any detectable growth phenotype when tested under multiple conditions (Heier et al. 2010).

Stationary phase cells shifted into fresh media rapidly initiate TAG and steryl ester breakdown, which leads to almost full depletion of cellular LD pools within 4–6 hr in lag phase. This initial phase of TAG breakdown is governed by the activity of TGL3- and TGL4-encoded lipases on LD and the tgl3Δtgl4Δ mutant strain exhibits a delay in entering vegetative growth during exit from stationary phase (Kurat et al. 2006). Tgl4 is constitutively present on LD and activation of Tgl4 by Cdc28p-dependent phosphorylation is involved in TAG lipolysis that contributes to bud formation exiting from stasis (Kurat et al. 2009). Resumption of growth following stasis is also dependent on the DGK1-encoded DAG kinase. In comparison to wild-type cells, stationary phase dgk1Δ cells fail to initiate growth when de novo FA synthesis is impaired. The dgk1Δ mutant also fails to mobilize TAG under these conditions and accumulates TAG, phenotypes that are partially suppressed by the pah1Δ mutation or by channeling DAG into PC synthesis when choline is present (Fakas et al. 2011).

TAG synthesis and breakdown are also coordinated with phospholipid metabolism during logarithmic growth. Mutants with defects in TAG hydrolysis exhibit decreased synthesis of inositol containing sphingolipids and decreased PC and PI content during active growth (Rajakumari et al. 2010). Furthermore, mutants defective in synthesis or hydrolysis of TAG exhibit reduced capacity to restore cellular levels of PI when exogenous inositol is resupplied following an interval of inositol starvation during logarithmic growth. Under these conditions, alterations in the synthesis of inositol-containing sphingolipids are also observed in the dga1Δlro1Δare1Δare2Δ strain (Gaspar et al. 2011).

Glycerolipid precursors

Fatty acid synthesis and regulation:

The FA that are esterified to phospholipids and TAG are derived from de novo synthesis, the growth medium, and from lipid turnover (Tehlivets et al. 2007). The spectrum of FA in yeast consists mainly of C16 and C18 FA that are either saturated or monounsaturated, harboring a single double bond between carbon atoms 9 and 10 (Δ9 desaturation). Whereas de novo FA synthesis mostly takes place in the cytosol, all the enzymes involved in FA desaturation and elongation are associated with the ER membrane (Table 2) (Tehlivets et al. 2007).

Minor FA species are C12, C14, and very long chain FA, up to C26. However, FA compositions vary substantially between strains and are also dependent on cultivation conditions (Martin et al. 2007). Two different FA synthesis pathways exist in yeast, as in mammalian cells (Tehlivets et al. 2007): the major cytosolic pathway, which resembles the “eukaryotic” type I pathway and is responsible for the bulk synthesis of all major FA, and the mitochondrial (type II pathway), which is organized similarly to the bacterial FA biosynthetic pathway (Hiltunen et al. 2010). The latter is believed to synthesize FA up to C8 carbons, which serve as precursors for the synthesis of lipoic acid. Cytosolic FA synthesis is initiated by the ACC1-encoded acetyl-CoA carboxylase, which synthesizes malonyl-CoA from acetyl-CoA (Al-Feel et al. 1992; Hasslacher et al. 1993). This reaction requires a covalently bound biotin prosthetic group, which is attached to lysine735 in the biotin-carrier domain of Acc1 by the BPL1-encoded biotin:apoprotein ligase. The FA synthase complex is composed of two subunits, encoded by FAS1 (Fas1, β-subunit) and FAS2 (Fas2, α-subunit) and is organized as an α6/β6 heterooligomeric complex (Kuziora et al. 1983; Schweizer et al. 1986; Chirala et al. 1987). Fas2 carries a pantetheine prostetic group on the acyl-carrier protein (ACP) domain, which is a central element in a cycling series of reactions. In a first condensation step, malonyl-CoA is condensed with pantetheine-bound acetyl-CoA to form 3-keto-acyl-ACP, which is reduced to 3-hydroxyacyl-ACP, dehydrated to 2,3-trans-enoyl-ACP, and further reduced to acyl(C+2)-ACP. Both reduction steps require NADPH and, as a result, FA synthesis is a major consumer of this dinucleotide. This multistep process results in the addition of two carbon units to the growing FA chain and cycles up to seven times, resulting in acyl-chains typically of 16 carbon atoms. The newly formed FA is transferred to coenzyme A, to yield cytosolic long chain acyl-CoA (Tehlivets et al. 2007). Acyl-CoA molecules are precursors for all acylation reactions involved in the synthesis of phospholipids, TAG, long chain bases, ceramide, and steryl esters, and also serve as precursors in protein acylation. The acyl-CoAs, whether derived from FA de novo synthesis or lipid recycling, are subject to elongation and desaturation, yielding the typical pattern of saturated and unsaturated FA species (see below). Yeast also contains an ACB1-encoded acyl-CoA binding protein, which plays an important regulatory function in delivering acyl-CoA into various pathways (Schjerling et al. 1996; Gaigg et al. 2001; Faergeman et al. 2004; Rijken et al. 2009). Mitochondrial FA synthesis involves enzymatic steps similar to those catalyzed by the cytosolic FAS complex. However, in contrast to cytosolic FA synthesis, but resembling archae- and eubacterial type II fatty acid synthase, the reactions of FA synthesis in mitochondria are catalyzed by individual polypeptides, encoded by separate genes (Hiltunen et al. 2010).

Defects in the FAS1 or FAS2 genes encoding cytosolic FA synthase lead to FA auxotrophy and can typically be rescued by the addition of exogenous C14 or C16 FAs. However, defects in ACC1 (Hasslacher et al. 1993) and BPL2 are lethal and cannot be suppressed by the addition of long chain FA. The essential role of these genes, when exogenous C14 and C16 FAs are present, is most likely the requirement for malonyl-CoA in the synthesis of essential VLCFA, which are components of glycerophosphoinositol (GPI) anchors and sphingolipids (Pittet and Conzelmann 2007; Dickson 2008; Dickson 2010). The synthesis of VLCFAs is accomplished by an ER membrane-localized elongase complex that acts on long chain acyl-CoA, consisting of the condensing enzymes encoded by ELO1, ELO2, and ELO3 (Oh et al. 1997), the β-ketoacyl-CoA reductase encoded by gene YBR159w (Han et al. 2002), the dehydratase encoded by PHS1 (Denic and Weissman 2007; Kihara et al. 2008), and the enoyl-CoA reductase, encoded by TSC13 (Kohlwein et al. 2001). Tsc13 accumulates within a specialized region of the ER in juxtaposition to the vacuole, termed the nucleus-vacuole junction (Pan et al. 2000) through interaction with Osh1p and Nvj1p (Kvam et al. 2005). The physiological role for a localization of just one component of the FA elongation complex to this subregion of the ER is currently unclear, but indicates a role for VLCFA in the formation of microautophagic vesicles involved in piecemeal autophagy of the nucleus (Kvam et al. 2005). Triple mutations in all three condensing enzyme genes as well as mutations in PHS1 or TSC13 are lethal, further supporting the notion that VLCFAs are essential in yeast. Yeast also harbors a single FA Δ9-desaturase encoded by OLE1, which localizes to the ER (Stukey et al. 1989) and mutants defective in Ole1 require exogenous C16:1 or C18:1 FA for growth. Since FA desaturation is an oxygen-dependent process (see below), growth of yeast under anaerobic conditions also requires the supplementation of these unsaturated FA.

In the absence of de novo FA synthesis or desaturation, as in fas1, fas2, or ole1 mutants, and in wild-type cells under anaerobic conditions, cellular growth is dependent on an exogenous supply of FA. Under these conditions, the activity of acyl-CoA synthetases (Table 2), encoded by FAA1, FAA2, FAA3, FAA4, and FAT1 (Duronio et al. 1992; Harington et al. 1994; Johnson et al. 1994a,b; Watkins et al. 1998; Choi and Martin 1999; Black and Dirusso 2007) is also required. The acyl-CoA synthetases activate free FA with coenzyme A in an ATP-dependent reaction, and are also believed to be required for FA uptake into yeast cells (Faergeman et al. 2001; Black and Dirusso 2007; Obermeyer et al. 2007). Acyl-CoA synthetases differ in their substrate specificity and subcellular localization and are present in the ER membrane, plasma membrane, peroxisome, and LD (Natter et al. 2005; Black and Dirusso 2007). The acyl-CoA synthetase Faa2 and the enzymes for FA β-oxidation, a cyclic series of reactions breaking down FA into acetyl-CoA and generating FADH2 and NADH, are localized to the peroxisomes (planned YeastBook chapter “Lipid particles and peroxisomes” by Kohlwein and van der Klei). FA uptake into yeast cells is also mediated by an endocytotic mechanism that requires the activity of Ypk1, the yeast ortholog of the human serum- and glucocorticoid-induced kinase (Jacquier and Schneiter 2010). In the absence of acyl-CoA synthetases, FA released by lipid turnover (see above) cannot be activated and utilized for lipid synthesis. For this reason, mutants lacking these activities excrete FA (Scharnewski et al. 2008).

FA synthesis is regulated at multiple levels (Tehlivets et al. 2007). ACC1, FAS1, and FAS2 expression is under control of an UASINO element and coregulated with genes involved in phospholipid synthesis (Chirala 1992; Schuller et al. 1992) (see below). ACC1 expression is also regulated by the SAGA protein complex and TFIID (Huisinga and Pugh 2004) and may therefore depend on histone acetylation. ACC1 expression was also found to fluctuate during the cell division cycle, with a peak of expression in early G1 phase (Cho et al. 1998). Compensatory changes in ACC1 expression in mutants defective in Acc1 activity indicate an autoregulatory loop (Shirra et al. 2001). Expression of the FAS1 and FAS2 genes is regulated by the transcription factors Gcr1, Reb1, Rap1, and Abf1 (Schuller et al. 1994; Greenberg and Lopes 1996) and repressed by long chain FA (Chirala 1992). FAS1 is also regulated by the SAGA complex and TFIID, and both genes show cell cycle-dependent expression, with a peak level at M/G1 (Spellman et al. 1998; Huisinga and Pugh 2004).

Acc1 enzyme activity is greatly elevated in the snf1Δ mutant and the data are consistent with Acc1 being a substrate of AMP-activated protein kinase, encoded by the SNF1 (Woods et al. 1994; Shirra et al. 2001). Snf1 also regulates chromatin by phosphorylating histones among other proteins and, therefore, has multiple effects on expression of genes, including ACC1, FAS1, and FAS2. Notably, FAS1 and FAS2 promoter sequences differ, and the stoichiometry of the FAS complex is established both by the level of FAS1 gene expression and Fas1 protein abundance (Schuller et al. 1992; Wenz et al. 2001; Tehlivets et al. 2007). Excess of either protein is rapidly eliminated by degradation via vacuolar proteases (Fas1) or ubiquitination and proteasomal digestion (Fas2), respectively (Peng et al. 2003).

Knowledge about the regulation of FA elongation leading to VLCFA synthesis is limited. Microarray experiments have shown that ELO1 expression is upregulated in the presence of myristic acid (C14:0), consistent with the preference of the Elo1 protein for this FA (Toke and Martin 1996). Expression of ELO1, ELO2, and ELO3 genes also responds to stationary phase, nitrogen limitation, glycosylation defects, or α-factor treatment, indicating a regulatory cross-talk between nutritional state and cell proliferation to VLCFA synthesis (Gasch et al. 2000).

Ole1 is a nonheme iron-containing integral ER membrane protein (Table 2), which harbors an intrinsic cytochrome b5 domain as an electron carrier (Martin et al. 2007). To subtract two electrons and two protons from the saturated acyl-chain and transfer them to oxygen, Ole1 activity is complemented by the activity of an NADH cytochrome b5 reductase (dehydrogenase) that is also localized to the ER. Desaturation of FA by Ole1 is a highly regulated, oxygen-requiring process (Martin et al. 2007), which is discussed in detail in the section below on cell biology of lipids.

Water soluble precursors of phospholipids, metabolism, and regulatory roles:

A number of water-soluble molecules used in phospholipid synthesis, including inositol, choline, ethanolamine, serine, CTP, and S-adenosyl methionine (AdoMet) and the enzymes involved in these reactions are largely cytosolic (Table 2). However, choline and ethanolamine are produced in yeast in the context of ongoing synthesis and turnover of PE and PC in the membranes as discussed above. Considerable attention has been paid to inositol and CTP, which have major regulatory roles in phospholipid metabolism. The effects of inositol on transcriptional regulation UASINO-containing phospholipid biosynthetic genes controlled by the Opi1 repressor are shown in Figure 3 and will be discussed in a subsequent section. The regulatory effects of the soluble metabolites inositol, CTP, and S-adenosyl homocysteine (AdoHcy) on enzyme activity and metabolic flux in the CDP-DAG pathway (Figure 4) are discussed here.

Inositol is the precursor to PI (Figure 2), which is essential to the synthesis of polyphosphoinositides (Strahl and Thorner 2007), sphingolipids (Cowart and Obeid 2007; Dickson 2008, 2010), and GPI anchors (Pittet and Conzelmann 2007). Inositol is derived from glucose-6-P via the reactions catalyzed by the cytosolic INO1-encoded inositol-3-P synthase (Donahue and Henry 1981; Klig and Henry 1984; Dean-Johnson and Henry 1989) and the INM1-encoded inositol-3-P phosphatase (Murray and Greenberg 2000). Exogenously supplied inositol stimulates PI synthase and inhibits PS synthase activity, alleviating the competition with PI synthase for their common substrate, CDP-DAG (Figure 4). The presence of exogenous inositol leads to increased PI synthesis and reduced levels of both CDP-DAG and its precursor PA in wild-type cells (Kelley et al. 1988; Loewen et al. 2004). TAG, which is derived from PA by the action of Pah1 (Figure 2), is decreased in the presence of inositol and increases in its absence (Gaspar et al. 2006, 2011). In addition, the levels of the complex sphingolipids, which are derived from PI, are reduced when cells are deprived of inositol and increase when inositol is supplied (Becker and Lester 1977; Hanson and Lester 1980; Jesch et al. 2010). The changes that occur in phospholipid synthesis and composition in response to exogenous serine (Kelley et al. 1988) and choline (Gaspar et al. 2006) are much less dramatic than the effects of exogenous inositol. However, when inositol is present in the growth medium, serine (Homann et al.1987), ethanolamine, and choline (Poole et al. 1986) result in the reduction of the activities of PS synthase and CDP-DAG synthase at the transcriptional level (see below). Exogenous choline also results in a dramatic change in the rate and mechanism of PC turnover, leading to a switch from a phospholipase D to a phospholipase B-mediated route (Dowd et al. 2001). The phospholipase responsible for turnover of PC under these conditions is Nte1 (Zaccheo et al. 2004).

CTP is derived from UTP by the cytosolic URA7- and URA8-encoded CTP synthetase enzymes (Ozier-Kalogeropoulos et al. 1991, 1994).

The nucleotide CTP plays a critical role in phospholipid synthesis as the direct precursor of the high-energy intermediates CDP-DAG, CDP-choline, and CDP-ethanolamine that are used in the CDP-DAG and Kennedy pathways (Figure 2) (Chang and Carman 2008). It is also used as the phosphate donor for the synthesis of PA by DAG kinase (Han et al. 2008b). CTP synthetase (Ozier-Kalogeropoulos et al. 1991, 1994) that produces CTP is allosterically inhibited by the product (Yang et al. 1994; Nadkarni et al. 1995), and this regulation ultimately determines the intracellular concentration of CTP (Yang et al. 1994; McDonough et al. 1995). CTP inhibits the CTP synthetase activity by increasing the positive cooperativity of the enzyme for UTP, and at the same time by decreasing the affinity for UTP (Yang et al. 1994; Nadkarni et al. 1995). However, CTP synthetases containing an E161K mutation are less sensitive to CTP product inhibition (Ostrander et al. 1998), and cells expressing the mutant enzymes exhibit a 6- to 15-fold increase in the CTP level (Ostrander et al. 1998). They also show alterations in the synthesis of membrane phospholipids, which include a decrease in the amounts of PS and increases in the amounts of PC, PE, and PA (Ostrander et al. 1998). The decrease in the amount of PS results from direct inhibition of PS synthase activity by CTP (McDonough et al. 1995), and this inhibition favors the synthesis of phospholipids by the Kennedy pathway (Figure 4). The increase in PC synthesis is ascribed to a higher utilization of the CDP-choline branch of the Kennedy pathway due to the stimulation of choline P cytidylyltransferase activity (McDonough et al. 1995; Ostrander et al. 1998) by increased substrate availability of CTP (McDonough et al. 1995; Kent and Carman 1999). Likewise, the increase in PE synthesis could be attributed to stimulation of ethanolamine-P cytidylyltransferase activity. The increase in PA content may result from the stimulation of DAG kinase activity by increased availability of its substrate CTP (Han et al. 2008b). CTP also inhibits the activity of Pah1 (Wu and Carman 1994), another factor that contributes to an elevation of PA content. The cells expressing the E161K mutant CTP synthase excrete inositol (Ostrander et al. 1998), a characteristic phenotype that typifies the misregulation of UASINO-containing phospholipid synthesis genes (see below) in cells that accumulate an excess of PA (Carman and Henry 2007). It is unclear whether UASINO-containing genes in the CDP-DAG and Kennedy pathways are derepressed in CTP overproducing cells, but the overriding regulation that governs the utilization of the two pathways appears to be biochemical in nature.

AdoHcy is a product of the AdoMet-dependent methylation reactions that are catalyzed by Cho2 and Opi3 in the CDP-DAG pathway (Figure 2). SAH1-encoded AdoHcy hydrolase (Malanovic et al. 2008) requires NADH for the hydrolytic breakdown of AdoHcy to adenosine and homocysteine (Takata et al. 2002). AdoHcy (Figure 4) is a competitive inhibitor of the phospholipid methyltransferase enzymes (Gaynor and Carman 1990). Thus, down-regulation of the AdoHcy hydrolase causes the accumulation of AdoHcy and the inhibition of PC synthesis, which leads to an increase in PA content and consequently, as described below, to the derepression of UASINO-containing genes (Malanovic et al. 2008). Although the effects of AdoHcy on phospholipid composition have not been addressed, its accumulation causes an increase in TAG synthesis and LD content (Malanovic et al. 2008), further underscoring the metabolic interconnection between phospholipid and TAG homeostasis discussed above.

Cell Biology of Lipids

In yeast, most subcellular membranes are composed of similar glycerophospholipid classes but the quantitative phospholipid composition of subcellular organelles differs substantially (Schneiter et al. 1999). Moreover, as described above, multiple cellular organelles and compartments contribute to glycerolipid metabolism (Figure 2, Tables 1–3). While multiple compartments contribute to lipid synthesis in yeast (Zinser et al. 1991; Natter et al. 2005), most reactions are confined to single membrane compartments. Thus, extensive regulated flux of lipids, across and among individual membranes and organelles, is required to enable the cell to adjust lipid composition in specific compartments under changing growth conditions. A number of mechanisms involved in these complex interactions have been identified.

For example, a set of membrane-bound flippases are known to govern transmembrane movement of phospholipids (Pomorski et al. 2004; Holthuis and Levine 2005). Intermembrane transfer of lipids is facilitated by a family of proteins, termed oxysterol-binding protein (OSBP) related proteins (ORP), of which seven members, Osh1–7, with overlapping functions, exist in yeast (Beh and Rine 2004). Some of the yeast Osh proteins have been localized to membrane contacts sites (Levine and Loewen 2006; Raychaudhuri and Prinz 2010). While none of these genes individually are essential, simultaneous deletion of all seven OSH genes is lethal and conditional alleles, following a shift to restrictive conditions, result in pleiotropic effects on vesicular trafficking and phospholipid and sterol composition of membranes, as do combinations of individual deletions (Beh and Rine 2004; Fei et al. 2008). The six members of the Sec14 superfamily constitute another major class of proteins involved in sensing and regulating membrane lipid composition (Griac 2007; Bankaitis et al. 2010). The five Sec14 homologs (Sfh1–5) share 28–76% similarity to Sec14 (Griac 2007) and localize to multiple subcellular organelles (Schnabl et al. 2003). Sec14, which performs an essential function at the Golgi, was originally identified as a PI/PC transfer protein, but its role in establishing phospholipid homeostasis is complex (Bankaitis et al. 2010).

In some instances, movement of lipids between membrane compartments is required to carry out a sequence of reactions. For example, PS is synthesized in the ER, but the major PS decarboxylase, Psd1, is located in the mitochondria (Figure 2, Table 1). Subsequently, the PE produced by Psd1 must be transported back to the ER to undergo methylation leading to PC. PS is transported into the mitochondria by an ubiquitin-regulated process that is insensitive to disruption of vesicular trafficking and involves specialized regions of apposition of mitochondria and ER known as the mitochondria-associated ER or MAM (Clancey et al. 1993; Trotter et al. 1993; Trotter and Voelker 1995; Achleitner et al. 1999; Voelker 2003; Osman et al. 2011). An ER–mitochondria tethering complex potentially involved in movement of phospholipids between the ER and mitochondria has been described (Kornmann et al. 2009).

The complex relationship between phospholipid metabolism in the ER and the synthesis and breakdown of cytosolic LD represents another example of the intricate interaction among cellular compartments that occurs in the course of lipid metabolism. LD are not merely storage depots for TAG and steryl esters. They are metabolically active; harboring multiple enzymes involved in lipid metabolism (Athenstaedt et al. 1999a; Rajakumari et al. 2008; Goodmann 2009; Kohlwein 2010b) (See also chapter: Lipid Droplets and Peroxisomes). Interaction of LD with the ER, mitochondria, and peroxisomes has been reported (Goodmann 2009). Pah1 clearly plays a critical role in TAG synthesis, LD formation, and the balance between nuclear/ER membrane proliferation and LD formation (Carman and Han 2009a; Adeyo et al. 2011). Several enzymes involved in TAG synthesis show a dual localization to the ER and LD (Figure 2, Table 1), including acyl-DHAP reductase (Ayr1), glycerol-3-P acyltransferase (Gpt2), and acyl-CoA–dependent DAG acyltransferase (Dga1). Formation of LD is believed to occur between the leaflets of the ER membrane, but alternative models such as vesicular trafficking have also been suggested (Thiele and Spandl 2008; Farese and Walther 2009; Guo et al. 2009). The close interaction of LD with mitochondria and peroxisomes also underscores the important role of LD in metabolism (Goodmann 2009). TAG levels fluctuate drastically during cellular growth and division, and multiple conditions contribute to the level of TAG storage in LD in stationary phase cells (Kurat et al. 2006; Czabany et al. 2007; Daum et al. 2007; Rajakumari et al. 2008; Zanghellini et al. 2008). As cells exit stationary phase, TAG hydrolysis supplies precursors for membrane lipid synthesis. As active cellular growth progresses, de novo FA synthesis increases, satisfying cellular requirements for lipid synthesis but even while TAG turnover is still in progress, de novo formation of TAG and LD is initiated (Kurat et al. 2006; Zanghellini et al. 2008). Methods for imaging-based screening of mutant libraries have been designed to identify factors involved in LD content, morphology, and mobilization (Wolinski and Kohlwein 2008; Wolinski et al. 2009) and screens using such methods have identified >200 genes that potentially influence these processes (Szymanski et al. 2007; Fei et al. 2008). However, there is surprisingly little overlap between the mutants identified in the published screens, indicating that current screens are far from being saturated.

Roles of lipids in organelle function and morphology

Due to the ubiquitous presence of most phospholipids in all subcellular membranes it can be difficult to assess specific phospholipid functions, in particular organelles. However, quite specific functions have been attributed to several lipids in the mitochondrion. For example, PE synthesized in the mitochondria by Psd1 plays an important role in stabilizing mitochondrial protein complexes (Birner et al. 2003; Osman et al. 2009a). Consequently, the psd1Δ mutant is nonviable in conjunction with defects in components of the prohibitin complex, which functions as a protein and lipid scaffold and ensures the integrity and functionality of the mitochondrial inner membrane (Osman et al. 2009b; Potting et al. 2010; van Gestel et al. 2010; Osman et al. 2011). In another example, CL, which is present only in the mitochondrion (Li, G. et al. 2007), plays an important role in mitochondrial genome stabilization and higher order organization of components of the mitochondrial respiratory chain (Koshkin and Greenberg 2002; Zhang et al. 2003; Zhong et al. 2004; Mileykovskaya et al. 2005; Joshi et al. 2009). However, CL function reaches beyond the mitochondria, indirectly regulating morphology and acidification of the vacuole through the retrograde (RTG2) signaling pathway and the NHX1-encoded vacuolar Na+/H+ exchanger (Chen et al. 2008). Lack of CL in crd1Δ mutants is in part compensated by an upregulation of the PE content, which is dependent on the mitochondrial synthesis through Psd1 (Gohil et al. 2005). Defects in Crd1 are also, in part, compensated by an increase in the precursor lipid PGP. Accordingly, mutation of the PGS1 gene encoding PGP synthase leads to more pronounced mitochondrial defects and a petite negative phenotype (Janitor et al. 1996; Chang et al. 1998a).

Alterations in organelle morphology and/or function observed in response to changes in lipid composition due to mutation or pharmacological inhibition of enzymes (Schneiter and Kohlwein 1997) provide tantalizing clues as to the roles of specific lipids. Notably, the pah1Δ mutant exhibits the expansion of the nuclear/ER membrane and up-regulation of phospholipid biosynthesis genes (Santos-Rosa et al. 2005). As discussed previously, dephosphorylation of PA by Pah1 provides DAG for the synthesis of TAG, as well as PE and PC in the Kennedy pathway. Consequently, the pah1Δ mutant has elevated PA levels, which result in up-regulation of phospholipid biosynthesis (see below) and membrane proliferation (Han et al. 2005; Carman and Henry 2007; Carman and Han 2009b). A number of mutants defective in FA metabolism also exhibit morphological abnormalities. For example, conditional mutants defective in FA desaturation (ole1/mdm2) show defective mitochondrial morphology and distribution upon cell division (Stewart and Yaffe 1991; Tatzer et al. 2002). The finding that several dozen proteins species are required to sustain cell viability in the presence of unsaturated FA suggests an enormously complex network of processes and interactions to maintain membrane homeostasis and function (Lockshon et al. 2007). In another example, a conditional acc1 mutant defective in FA de novo synthesis has impaired morphology of the vacuole due to reduced acylation of Vac8 that is involved in stabilizing the vacuolar membrane and vacuole inheritance (Schneiter et al. 2000). Mutants defective in FA elongation show similar fragmentation of the vacuole due to impaired synthesis of sphingolipids, which are important for the stability of the vacuolar ATPase complex (Chung et al. 2003).

Due to their important roles in protein modification, myristic and palmitic acid affect the membrane association of numerous proteins and consequently influence signaling, membrane function and organelle morphology (Dietrich and Ungermann 2004). NMT1 encodes the essential N-myristoyl transferase that attaches coenzyme A-activated myristic acid (C14-CoA) to a glycine residue close to the N-terminus of target proteins, resulting in cleavage of the peptide bond and N-terminal glycine acylation (Towler et al. 1987). Although the myristoyl residue is shorter than the typical C16 or C18 chain length found in membrane phospholipids and, therefore may not fully interdigitate into a membrane leaflet, it serves an essential function in promoting membrane association of proteins (Duronio et al. 1989). Palmitoylation of internal cysteine residues within the peptide chain plays an important role in post-translational modification of some 50 proteins in yeast (Roth et al. 2006), modulating membrane association, folding and activity. Protein palmitoylation is catalyzed by seven members of the “Asp-His-His-Cys-cystein-rich“ (DHHC-CRD) domain family of proteins, and includes the Erf2/Shr5 complex, Akr1, Akr2, Pfa3, Pfa4, Pfa5, and Swf1. Among the substrates for palmitoylation are Vac8, SNAREs, and Ras2, indicating important regulatory functions for this FA modification of proteins in multiple pathways involved in membrane trafficking and signaling.

Mechanisms of compartmentalization and localization of enzymes of lipid metabolism

Many enzymes involved in glycerolipid metabolism have transmembrane domains (Tables 1–3), which anchor the proteins in their specific membrane environment and promote access to hydrophobic lipid substrates. However, several membrane-associated enzymes lack defined transmembrane spanning domains and membrane interaction is mediated, perhaps in a regulated manner, with specific membrane-resident anchor proteins. For example, PIK1-encoded PI 4-kinase binds to the membrane through Frq1 and the VPS34-encoded PI 3-kinase binds through Vps15 (Strahl and Thorner 2007). In addition, enzymes may bind to the membrane through specific interaction with lipids in the membrane, such as PI 3-P, PI 4-P, PI 3,5-P2 and PI 4,5-P2 through PH, PX, FYVE or ENTH domains (Strahl and Thorner 2007). A number of enzymes involved in lipid biosynthesis utilize water soluble lipid precursors, including the choline and ethanolamine kinases and the enzymes of the FAS complex, involved in long chain FA synthesis, and are localized to the cytosol. Acyl-CoA, generated by the FAS complex, has a highly amphiphilic structure and easily associates with membrane surfaces, facilitating the subsequent incorporation of the acyl chains into lipids by membrane-bound enzymes. However, Pah1 is an example of an enzyme that is associated with both cytosolic and membrane compartments. PA, the substrate for Pah1, is present in the membrane, but the largest pool of Pah1 is cytosolic, highly phosphorylated and inactive. Pah1 must be dephosphorylated by the Nem1-Spo7 complex in order to be functional in vivo (Santos-Rosa et al. 2005; Han et al. 2006; Carman and Han 2009a; Choi et al. 2011). Dephosphorylation of Pah1 by the Nem1-Spo7 complex leads to its membrane association and its activation (Choi et al. 2011), leading to the production of DAG and TAG and the lowering of PA levels, which in turn affects regulation of phospholipid biosynthetic genes (see below) (Carman and Henry 2007; Carman and Han 2009b).

Regulation of lipid metabolism in response to membrane function

Several regulatory circuits have been uncovered that govern, by different mechanisms, the cross-talk between membrane function and lipid synthesis. Proteins involved in this regulation may sense specific changes in lipid composition, membrane charge, fluidity, or curvature. One such mechanism controls the expression of the fatty acid desaturase, Ole1, by the ER membrane-bound transcription factors Mga2 and Spt23, which are cleaved and released from the membrane in response to changes in membrane fluidity or permeability (Hoppe et al. 2000). Both proteins are synthesized as larger, ER membrane-bound proteins that are ubiquitinated and cleaved by the activity of the 26S proteasome under low oxygen conditions, in conjunction with the ubiquitin-selective chaperone CDC48UFD1/NPL4. This cleavage detaches the soluble fragments from their membrane anchors, and allows them to enter the nucleus to control transcription of OLE1 and several other genes through the low oxygen response (LORE) promoter element. Proteasomal cleavage of Mga2 and Spt23 requires the essential E3 ubiquitin ligase, Rsp5, and lack of this activity results in a cellular requirement for unsaturated FA. Cleavage of Spt23 and Mga2 in the ER is believed to be regulated by the membrane environment, adjusting membrane lipid composition through the control of FA desaturation. Under normoxic conditions, OLE1 expression is activated by the oxygen-responsive transcription factor Hap1. Addition of unsaturated FA, including linoleic acid (C18:2) or arachidonic acid (C20:4), which are normally not present in yeast, results in a drastic and rapid reduction of OLE1 mRNA expression and stability. However, low oxygen tension leads to a massive induction of OLE1 expression through the LORE element present in its promoter. This induction is believed to increase efficiency of FA desaturation to support cellular growth under oxygen limiting (hypoxic) conditions (Martin et al. 2007; see also the chapter on Lipid Droplets and Peroxisomes for more discussion of fatty acid metabolism and regulation). Mga2 (but not Spt23) was also shown to be responsible for the rapid, but transient, up-regulation of OLE1 and other LORE-containing genes observed when inositol is added to cultures of wild-type yeast growing logarithmically in the absence of inositol (Jesch et al. 2006). Regulation of the phospholipid biosynthetic genes containing the UASINO promoter element also occurs in response to changes in the lipid composition in the ER membrane, through the binding of the Opi1 repressor to PA (see below). The ER is also the locus of complex regulatory cross-talk involving membrane expansion, the secretory pathway, the unfolded protein response (UPR) pathway, and phospholipid metabolism (Cox et al. 1997; Travers et al. 2000; Block-Alper et al. 2002; Chang et al. 2002, 2004; Hyde et al. 2002; Brickner and Walter 2004; Jesch et al. 2006; Gaspar et al. 2008; Schuck et al. 2009).

Another example of regulation of lipid metabolism in yeast in response to changing membrane conditions was discovered in the course of analysis of a cho2Δopi3Δ mutant strain completely defective in PC formation via the PE methylation pathway (Boumann et al. 2006). When this mutant is deprived of choline, PC levels decline and as this process progresses, concomitant changes in acyl-chain distribution occur in PC and other phospholipids, especially PE. However, similar changes were not observed in the neutral lipid fraction. The shortening and increased saturation of PE acyl chains decreases the bilayer forming potential of PE and Boumann et al. (2006) suggest that phospholipid remodeling under these conditions may provide a mechanism for maintaining intrinsic membrane curvature. The nature of such a mechanism has not yet been defined, but yeast has a number of proteins harboring a BAR domain, including Rvs161 and Rvs167, which bind to liposomes in a curvature-dependent manner and promote tubule formation in vitro. In vivo studies in yeast indicate inappropriate regulation of phosphoinositide and sphingolipid metabolism impinges on Rsv161 and Rsv167 function (Ren et al. 2006; Youn et al. 2010). The Rim101 pathway, which is involved in regulating cellular pH in response to alkaline conditions and cell wall biogenesis, also appears to be involved in sensing membrane curvature (Mattiazzi et al. 2010).

Genetic Regulation of Glycerolipid Synthesis

In wild-type cells, both glycerolipid composition and the expression of lipid biosynthetic genes are influenced by a wide variety of growth conditions, including growth phase, temperature, pH, and the availability of nutrients such as carbon, nitrogen, phosphate, zinc, and lipid precursors. Transcript levels of certain lipid biosynthetic genes in yeast are also regulated by message stability. A number of viable mutants defective in genes encoding lipid metabolic enzymes, transporters, and regulatory factors exhibit changes in lipid composition. These complex and interrelated topics have been the subjects of numerous reports and reviews (Henry 1982; Carman and Henry 1989; Paltauf et al. 1992; Henry and Patton-Vogt 1998; Carman and Henry 1999; Gardocki et al. 2005; Jesch and Henry 2005b; Santos-Rosa et al. 2005; Carman and Henry 2007; Chen et al. 2007a; Daum et al. 2007; Gaspar et al. 2007; Li, G. et al. 2007; Patton-Vogt 2007; Gaspar et al. 2008; Schuiki et al. 2010; Young et al. 2010; Carman and Han 2011), as discussed below with a focus on the transcriptional regulation of lipid biosynthetic genes in response to PA.

Regulation of transcript abundance by mRNA degradation