Abstract

Fungi exhibit a large variety of morphological forms. Here, we examine the functions of a deeply conserved regulator of morphology in three fungal species: Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Candida albicans, and Histoplasma capsulatum. We show that, despite an estimated 600 million years since those species diverged from a common ancestor, Wor1 in C. albicans, Ryp1 in H. capsulatum, and Mit1 in S. cerevisiae are transcriptional regulators that recognize the same DNA sequence. Previous work established that Wor1 regulates white–opaque switching in C. albicans and that its ortholog Ryp1 regulates the yeast to mycelial transition in H. capsulatum. Here we show that the ortholog Mit1 in S. cerevisiae is also a master regulator of a morphological transition, in this case pseudohyphal growth. Full-genome chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments show that Mit1 binds to the control regions of the previously known regulators of pseudohyphal growth as well as those of many additional genes. Through a comparison of binding sites for Mit1 in S. cerevisiae, Wor1 in C. albicans, and Wor1 ectopically expressed in S. cerevisiae, we conclude that the genes controlled by the orthologous regulators overlap only slightly between these two species despite the fact that the DNA binding specificity of the regulators has remained largely unchanged. We suggest that the ancestral Wor1/Mit1/Ryp1 protein controlled aspects of cell morphology and that movement of genes in and out of the Wor1/Mit1/Ryp1 regulon is responsible, in part, for the differences of morphological forms among these species.

THE fungal kingdom collectively represents enormous evolutionary diversity, with estimates of >1 million species. Fungi exhibit a large variety of morphological forms ranging from single, budding yeast cells to hyphae (long chains of highly elongated cells) to mushrooms. Morphological differences among species can be seen at the single-cell level, but also encompass differences in the appearance of communities of cells such as colonies on solid medium. In this article, we examine aspects of morphological diversity over a limited range of fungal species including Saccharomyces cerevisiae (baker’s and brewer’s yeast), Candida albicans (a normal resident of the human gut but also the most prevalent fungal pathogen), and Histoplasma capsulatum (the cause of histoplasmosis in humans). These three species represent an estimated 200 million to 1.2 billion years of evolutionary divergence from a common ancestor (herein simplified to 600 million years) (Taylor and Berbee 2006). In all three species, a conserved, orthologous transcriptional regulator (Mit1/Wor1/Ryp1) governs an aspect of morphology, but these morphologies differ between species.

The C. albicans Wor1 protein is a master regulator of a phenomenon known as white–opaque switching. White–opaque switching refers to the transition between two distinctive cell types, termed “white” and “opaque”, each of which is heritable for many generations (Lohse and Johnson 2009; Soll 2009). Switching between these cell types occurs stochastically approximately once every 104 cell generations under standard laboratory conditions, but environmental signals can influence the direction of the switch (Rikkerink et al. 1988). The two cell types are easily distinguishable: opaque cells are more elongated than white cells, have larger vacuoles, and have different cell wall structures when visualized by electron microscopy (Anderson and Soll 1987; Slutsky et al. 1987). Moreover, the appearance of white and opaque colonies is different on a wide variety of media: white cells form rounded, glossy, white-colored colonies, whereas opaque cells form flatter, dull, tan-colored colonies. The two cell types also differ in their mating competence (Miller and Johnson 2002), in their preferred environmental niche in the host (Kvaal et al. 1997, 1999; Lachke et al. 2003), and in their recognition by cells of the innate immune system (Geiger et al. 2004; Lohse and Johnson 2008). Most, if not all, of these differences arise through the differential expression of ∼20% of the genome between the two cell types (Lan et al. 2002; Tsong et al. 2003; Tuch et al. 2010). Wor1 is a transcriptional regulator that contains a novel DNA-binding domain termed WOPR (Lohse et al. 2010); full genome chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiments revealed that Wor1 binds to ∼170 intragenic regions (Zordan et al. 2007), including many that lie upstream of opaque-specific genes. C. albicans ΔΔwor1 cells are locked in the white form, whereas ectopically expressed WOR1 drives white cells into the opaque form (Huang et al. 2006; Srikantha et al. 2006; Zordan et al. 2006).

H. capsulatum, another human fungal pathogen, diverged from a common ancestor with C. albicans ∼600 million years ago (Taylor and Berbee 2006). In the soil, H. capsulatum exists primarily as mycelia—mats composed of tangled hyphae. When mycelial cells break off and are inhaled by a human, they rapidly convert to the disease-causing budding yeast form (Woods 2002; Holbrook and Rappleye 2008). This transition, triggered by a shift in temperature to 37°, involves differential expression of ∼20% of the genome (Nguyen and Sil 2008). RYP1, the ortholog of WOR1 in H. capsulatum, has been identified as a master regulator of this transition as Δryp1 strains are locked in the mycelial form (Nguyen and Sil 2008).

In this article, we show that Ryp1 and Wor1 are both transcriptional activators and that both act through the same DNA sequence motif despite the large evolutionary distance between the proteins. C. albicans and H. capsulatum, however, are too distantly related to meaningfully compare the target genes of these regulators; in particular, the orthology relationships between many genes in the two species are currently ambiguous. To address the question of transcriptional circuit diversification, we turned to a comparison between C. albicans and a much more closely related species, S. cerevisiae, with an estimated divergence time of between 100 and 600 million years (herein stated as 200 million years) (Taylor and Berbee 2006).

S. cerevisiae has two orthologs of WOR1, MIT1 (YEL007W) and YHR177W, as a result of a whole genome duplication that occurred before the Saccharomyces clade diverged. Two previous results suggested these genes were involved in the S. cerevisiae pseudohyphal growth program. First, overexpression of the C. albicans homolog WOR1 induced haploid invasive growth in the S. cerevisiae S288c laboratory strain, which is normally incapable of this behavior (Li and Palecek 2005; Huang et al. 2006). Second, inactivation of MIT1 in the “wild” strain Σ1278b compromised haploid invasive growth (E. Summers and G. R. Fink, unpublished communication). When the Σ1278b strain is starved for nutrients, its cells become elongated and remain attached to one another, forming chains of cells (filaments) known as pseudohyphae. These pseudohyphae grow outward and penetrate into the agar (Gimeno et al. 1992; Gagiano et al. 2002); this behavior can be monitored by plating Σ1278b on nutrient-limited agar, washing away the colonies, and visualizing the proliferation of cells trapped in the agar. Commonly described as a foraging response, this type of growth has been proposed to allow S. cerevisiae to explore new environments. Many common laboratory strains of S. cerevisiae do not exhibit this behavior due to mutations that accumulated during strain domestication (Liu et al. 1996). The inability of common laboratory strains to form pseudohyphae likely explains the sparsity of data for MIT1 or YHR177W in the many high-throughput data sets generated for S. cerevisiae.

Filamentous growth in S. cerevisiae Σ1278b requires a number of previously identified transcriptional regulators, including Mga1, Phd1, Sok2, Ste12, Tec1, and Flo8, and genome-wide ChIP analyses have shown that these six regulators regulate one another and a network of hundreds of downstream targets (Borneman et al. 2006, 2007a,b; Monteiro et al. 2008). Here we show that Mit1 is a central transcriptional regulator of the S. cerevisiae filamentous growth program. Mit1 is required for filamentous growth and its ectopic expression can drive filamentous growth under environmental conditions that normally disfavor it. Genome-wide ChIP experiments show that Mit1 directly binds to, and is bound by, most of the previously known transcriptional regulators of filamentous growth and can therefore be considered a core regulator (Borneman et al. 2006). Thus Wor1, Ryp1, and Mit1 are all central regulators of morphological transitions that are different from one species to the next.

Materials and Methods

Growth conditions

Standard laboratory media were used (Guthrie and Fink 1991). Cultures for all microarray and ChIP experiments were grown in YEP media supplemented with 2% glucose, except for the ChIP of Wor1 that was performed under SD −URA conditions to select for Wor1 expression. β-Galactosidase assays were performed in synthetic complete dextrose (SCD) media lacking URA, HIS, TRP, URA and TRP, or URA and HIS to maintain selection for plasmids. Synthetic low ammonium dextrose (SLAD) nitrogen starvation media for diploid invasive growth assays were prepared as previously described, washing agar three times to remove traces of nitrogen (Gimeno et al. 1992).

Strain construction

A list of yeast strains used in this study can be found in Supporting Information, Table S13. Strains were constructed in the S. cerevisiae Σ2000 background (a Σ1278b derivative), a gift from Hiten Madhani. Selectable markers for deleting genes were amplified with 50 bp of homology on each side of the gene to be replaced and transformed using standard methods (Longtine et al. 1998). Mit1-GFP was generated using a fusion of a S65T GFP cassette in frame at the C terminus of the protein, and nuclear localization was visualized as previously described (Huh et al. 2003).

Plasmids

A list of plasmids used in this study can be found in Table S14. A list of oligos can be found in Table S15. Plasmids for LacZ expression for β-galactosidase assays were derivatives of pLG669z. The previously reported plasmids PFLO11 2/1 to PFLO11 15/14 (Rupp et al. 1999) were used to analyze activity from 440-bp fragments of the FLO11 promoter. To further localize the region of Mit1 activity, reporter plasmids with 50-bp fragments, arranged to provide 25-bp overlap, were synthesized with XhoI compatible ends, annealed, and ligated into pLG669z digested with XhoI.

Versions of a selectable CEN-linked PTEF-containing plasmid were used for ectopic expression of proteins (Mumberg et al. 1995). RYP1 was overexpressed by amplifying its coding region from H. capsulatum G217B and ligating into a CEN-linked PTEF vector. The WOR1 overexpression vector was previously reported (Lohse et al. 2010). To create the MIT1 overexpression construct, the N-terminal portion of MIT1 extending to a HindIII site was PCR amplified and cloned into a CEN-linked PTEF vector. To complete the open reading frame, plasmid YGPM-25i24, containing a genomic fragment encompassing the entire MIT1 ORF, was obtained as a gift from the laboratory of Greg Prelich (Jones et al. 2008), digested with HindIII and SnaBII, and cloned in frame into the PTEF -5′MIT1 plasmid. This plasmid was transformed into XL1-Gold cells (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA).

To create 6-His–tagged Yhr177w and Mit1 protein expression plasmids, regions corresponding to amino acids 6–201 (Yhr177w) or 5–251 (Mit1) were amplified from genomic DNA and ligated into pLIC-H3 between XmaI and XhoI sites. pLIC-H3 is a pET28b derivative and was a gift from the laboratory of Jeff Cox at University of California, San Francisco.

Protein expression and purification

MBP-Wor1 1–321 expression and purification were performed as previously described (Lohse et al. 2010). 6-His–tagged Yhr177w 6–201 aa and Mit1 5–251 aa were expressed in LB media. Cells were induced at an OD of 0.5 with 0.4 mM IPTG and grown for 4 hr at 25°.

For purification, cells were resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 600 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, pH 8.0) supplemented with 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 1 mg/ml lysozyme, and one Complete Mini Protease inhibitor cocktail tablet, EDTA-free (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) per 10-ml vol. Resuspended cells were incubated at 4° for 20 min, sonicated, and incubated with 50 units/ml DNaseI for 30 min at 4°. The lysate was centrifuged and then run over Ni-NTA agarose columns (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA), which were washed with 20 column volumes of wash media (50 mM NaH2PO4, 600 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, pH 8.0) followed by 5 column volumes of elution buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 600 mM NaCl, 250 mM imidazole, pH 8.0). Elution fractions were stored in 10 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM DTT, and 50% glycerol.

Electromobility gel shift assays

Electromobility gel shift Assays were performed as previously described (Lohse et al. 2010), using the 50-bp 1175–1225 fragment from S. cerevisiae PFLO11 or the mutated version of this fragment.

Invasion assays

Haploid invasion assays were performed as previously described (Lo and Dranginis 1998). Briefly, haploid invasion was assayed by plating cells on YEPD media for 2 days, washing them gently under a steady stream of running water for 20 sec, and photographing the remaining cells. Diploid pseudohyphal growth was tested by plating cells at a low density on SLAD agar, allowing individual colonies to form over 7 days, and then photographing colonies under a dissection scope. Ectopic induction of the pseudohyphal growth program was analyzed by patching diploid cells carrying MIT1, WOR1, or RYP1 overexpression plasmids on selectable SD media for 2 days and then washing them under a steady stream of running water. Pseudohyphal microcolonies were observed by plating cells at low density under a coverslip on a slide topped with selectable SD agar media. Microcolonies were allowed to form overnight and then were photographed at 63× magnification on an inverted Zeiss Axiovert 200 M microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany), using Axiovision software.

β-galactosidase assays

β-galactosidase assays were performed in triplicate using a standard protocol (Rupp 2002). Strains were grown in selectable media to maintain selection for plasmids. For each strain, cultures were grown overnight, diluted back, and allowed to reach log phase before harvesting.

Expression microarrays

A full discussion of this topic is presented in File S3. Microarray data have been uploaded to NCBI GEO (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under accession nos. GSE32558 (transcription arrays and ChIP-chip data) and GSE32550 (transcription arrays only).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

Chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments were performed as previously described (Nobile et al. 2009). Briefly, 200 ml of log-phase culture was cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde, quenched with 125 mM glycine, and harvested. Polyclonal anti-GFP antibody (ab290) was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA) and was used for Mit1-GFP experiments. Additional antibodies were generated against N-terminal and C-terminal peptide sequences from Mit1 and Yhr177w, by Bethyl (Montgomery, TX). C-terminal antibodies were used for all experiments with Yhr177w. Antibodies against Wor1 have been previously reported (Zordan et al. 2006, 2007). Yeast Chip on Chip arrays containing ∼244k probes with an average resolution of ∼50 nt were ordered from Agilent Technologies (Santa Clara, CA). These arrays were designed against the S. cerevisiae S288c reference strain, as the Σ genome sequence had not yet been completed; however, the minor sequence variation between these genomes would not impact our experiments. Mit1 and Yhr177w experiments and controls were each performed in duplicate; the Wor1 experiment and control were each performed once. Experimental analysis was performed using Agilent Chip Analytics Version 1.2 software and MochiView Version 1.45 (Homann and Johnson 2010). This process is explained in detail in File S3.

ChIP-chip data have been uploaded to NCBI GEO (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under accession nos. GSE32558 (ChIP-chip data and transcription arrays) and GSE32557 (ChIP-chip data only).

Binding site comparisons

Binding data for Sok2, Tec1, and Ste12 were taken from previously published studies (Borneman et al. 2007b). All data sets for binding site comparisons were processed in the following manner, using MochiView Version 1.45. This process is explained in detail in File S3.

Motif analysis

DNA motif analysis of Mit1 binding sites was performed using MochiView v1.45. Comparisons between the Mit1 and Wor1 motifs were performed in MochiView v1.45, which uses the approach presented in Gupta et al. (2007). A full discussion of this topic is presented in File S3.

Orthology mapping

The C. albicans Wor1 binding site list was previously reported (Zordan et al. 2007). Comparisons between the Mit1/Wor1 target lists were made using gene annotations from the Saccharomyces Genome Database (SGD) (http://www.yeastgenome.org/) and Candida Genome Database (CGD) (http://www.candidagenome.org/). Orthology annotation was obtained from the Fungal Orthogroups Repository (http://www.broadinstitute.org/regev/orthogroups/), which was generated by the SYNERGY algorithm (Wapinski et al. 2007). All files were downloaded on September 30, 2009. On the basis of additional information (Schweizer et al. 2000; Kadosh and Johnson 2001), changes were made to the mapping for three sets of genes prior to further analysis. These changes are discussed in detail in File S3; they do not substantially change the results of the bootstrap statistical analysis described below.

Bootstrap analysis of target overlap

We applied bootstrap statistics to test the hypothesis that the shared orthology between the S. cerevisiae and C. albicans gene lists exceeded the overlap that might be expected by chance. We considered only the 66 S. cerevisiae and 118 C. albicans targets with orthology mapping between the two species (Table S11 and Table S12).

After applying the hand annotations described above to the orthology annotations, 13 of the 66 S. cerevisiae orthology-mapped Mit1 targets share orthology with one or more genes in the Wor1 target list. Sets of 66 S. cerevisiae genes were sampled from the group of all S. cerevisiae genes with ortholog mappings (4524 genes) and tested to determine whether the number of genes in the set with shared orthology to genes in the Wor1 target list equaled or exceeded the observed 13-gene Mit1-to-Wor1 mapping. Only one sampled set met this standard, confirming a significant z (n = 1,000,000; P = 1 × 10−6). A reciprocal test yielded similar results, comparing the benchmark of 10 of 118 Wor1 targets that share orthology with the Mit1 gene list against sets of 118 genes sampled from the 4393 C. albicans genes with ortholog mappings (n = 1,000,000; P = 3.7 × 10−5). These statistical analyses also hold true without the hand-annotated changes to the orthology mapping (File S3).

Results

MIT1 is required for haploid invasive growth and diploid pseudohyphal growth

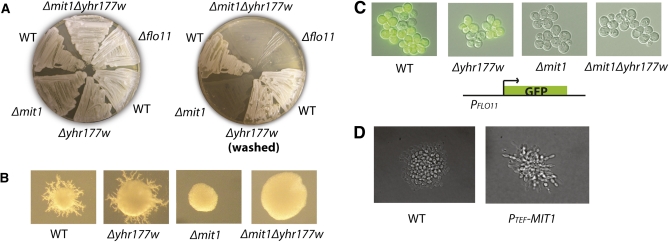

We deleted MIT1 in the Σ2000 background (a derivative of Σ1278b), which resulted in both a recapitulation of the unpublished invasion defect in haploid cells and a pseudohyphal growth defect in diploid cells (Figure 1, A and B). Deletion of YHR177W, the second S. cerevisiae ortholog of WOR1, had no effect on either phenotype. Previous studies have shown that expression of the cell wall floculin FLO11 (MUC1) is critical for filamentous growth (Lo and Dranginis 1998), and whole-genome expression experiments showed that FLO11 expression was at least 40-fold lower in a haploid Δmit1 strain relative to the unmodified parent strain (Table S1, File S1). When the FLO11 coding sequence was replaced with GFP, the Δmit1 strain exhibited a dramatic reduction in GFP production compared to the parent strain, providing further evidence that MIT1 is required for FLO11 expression (Figure 1C). The decrease in FLO11 expression likely accounts, at least in part, for the filament-defective phenotype of the Δmit1 strain.

Figure 1 .

MIT1 is required for haploid invasive growth, diploid pseudohyphal growth, and expression of FLO11 in S. cerevisiae. (A) Haploid invasive growth assay. Haploid a cells of the indicated genotypes (Σ2000 background) were plated on YPD agar plates, grown for 2 days at 30°, and washed. Pre- (left) and post- (right) wash images are shown. (B) Diploid pseudohyphal growth assay. Individual a/α diploid cells (Σ2000 background) were plated on SLAD agar plates, grown for 7 days, and then photographed. A representative colony from each plate is shown. Δmit1 and Δmit1Δyhr177w colonies were never observed to display pseudohyphal growth in this assay. (C) Expression of FLO11 is dependent on MIT1. The FLO11 coding sequence was replaced with GFP (S65T). Haploid a cells were grown in YPD to log phase, placed under a coverslip, and then photographed at 40× magnification. (D) MIT1 expressed from the TEF promoter drives diploid pseudohyphal growth in SD media conditions. Individual diploid Σ2000 cells were plated on an SD agar pad on a glass microscopy slide and allowed to grow under a coverslip at 30° for 16 hr, and then individual microcolonies were visualized at 40× magnification. Wild-type cells were not observed to display pseudohyphal growth while cells containing a plasmid expressing MIT1 from the TEF promoter displayed elongated morphology and agar penetration consistent with the pseudohyphal growth phenotype.

We next determined whether ectopic expression of MIT1 was sufficient to induce pseudohyphal growth under conditions where it does not normally take place. Indeed, ectopic expression of MIT1 from the TEF promoter drives diploid cells to invade agar in rich media conditions (Figure 1D). Thus, MIT1 fulfills the requirements of a “master regulator” of filamentous growth in that deletion of MIT1 prevents filamentous growth and ectopic expression of MIT1 drives it.

Mit1 is a core member of the S. cerevisiae filamentous growth circuit

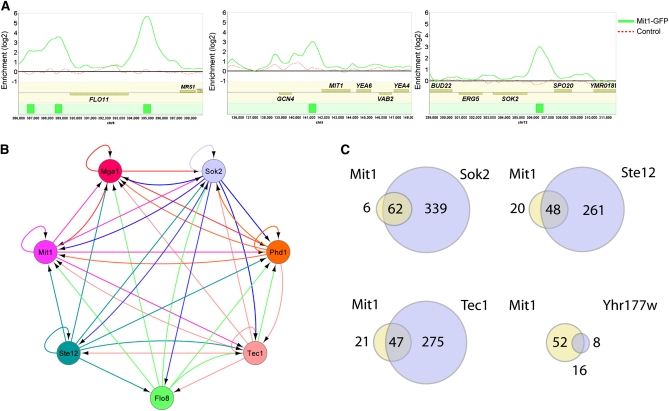

To better understand the role of Mit1 in regulating filamentous growth, we utilized chromatin immunoprecipitation combined with whole genome tiling microarrays (ChIP-Chip) to identify its direct downstream targets. A GFP tag was introduced to the C-terminal portion of Mit1 at its endogenous locus; GFP-tagged Mit1 was fully competent to promote invasive growth (not shown). Cross-linking, followed by DNA shearing and immunoprecipitation with antibodies directed against GFP, identified 74 discrete binding locations across the genome, corresponding to 68 intergenic regions positioned upstream of 94 genes (Figure 2A, Table S2, Table S3, Table S4, File S1, and File S2). These 74 locations were rigorously identified from two highly reproducible high-density tiling microarray experiments, minimizing false positives (see Materials and Methods). Four of the 5 known flocculin genes (FLO1, FLO9, FLO10, and FLO11 but not FLO5) are bound by Mit1, with the strongest enrichment detected upstream of FLO11. Transcriptional regulators were strongly enriched in the Mit1-bound gene set; Mit1 binding was found upstream of 21 genes encoding sequence-specific DNA-binding proteins, including MIT1 itself and most of the regulators previously implicated in filamentous growth (see below). We examined Mit1-bound locations to determine the DNA sequence specifically recognized by Mit1; we identified a motif that is present in ∼70% of Mit1-bound sites, using a stringency level that produces false positive hits in 20% of a control set of promoter regions (Figure S1, Table S5, File S1, and File S3). This DNA motif is nearly identical to the previously reported Wor1 motif (Lohse et al. 2010) (Figure S1).

Figure 2 .

MIT1 is a central transcriptional regulator of filamentous growth. (A) ChIP-chip plots illustrate binding of Mit1-GFP in Σ2000 haploid a cells to promoters of FLO11, MIT1, and SOK2. Experimental enrichment data are presented as a solid green line in each panel and control data from a wild-type untagged strain are presented as a dashed red line. The green boxes in the bottom track represent the called Mit1 binding sites. Data were visualized using Mochiview 1.45, with the x-axis representing the genomic location and the y-axis representing log2 enrichment. (B) The network of interactions between Mit1 and previously known diploid pseudohyphal growth regulators. Arrows indicate binding of a regulator at the promoter of a given regulator. Connections represent those previously reported for the other six regulators (Borneman et al. 2006, 2007b) and those from the Mit1 ChIP-chip data reported here. (C) A genome-wide binding analysis comparison of Mit1 and Yhr177w bound intergenic regions with those previously reported for Sok2, Ste12, and Tec1 (Borneman et al. 2007b) reveals a high degree of target gene overlap.

We also examined binding by the Mit1 paralog, Yhr177w, using two peptide-derived antibodies, but we did not observe any significant enrichment in a wild-type Σ2000 strain. However, YHR177W expression is upregulated approximately eightfold when MIT1 is deleted (Table S1), and in this strain we identified 24 intergenic regions bound by Yhr177w, positioned upstream of 34 genes (Table S6, Table S7, File S1, and File S4). Most of these regions (16/24) were also bound by Mit1 in the experiment described above, indicating that Yhr177w and Mit1 regulate many of the same genes and probably share DNA-binding specificities. It is likely that Yhr177w regulates pseudohyphal growth in some environments, but it did not play an obvious role under the conditions examined here; for example, the Δmit1 strain exhibited the same filament-deficient phenotype as the Δmit1Δyhr177w strain (Figure 1A) and ectopic expression of YHR177W had no visible phenotype in either wild-type or Δmit1 backgrounds.

We next examined whether Mit1 was an integral part of the transcriptional network regulating filamentous growth in S. cerevisiae. Previous ChIP-chip analysis of the regulators Phd1, Sok2, Mga1, Flo8, Tec1, and Ste12 identified a highly interactive regulatory network where each factor regulates, and is regulated by, most of the other transcriptional regulators (Figure 2B) (Borneman et al. 2006). All six of these proteins were previously reported to bind the upstream region of MIT1 (Monteiro et al. 2008) and the immunoprecipitation experiments presented in this article revealed that Mit1 binds to its own upstream region, as well as those of PHD1, SOK2, MGA1, and TEC1 (Figure 2B). Thus, Mit1 appears to be as integral a part of the pseudohyphal growth circuit as any of the previously known regulators.

To determine the extent to which Mit1 shares targets with the previously identified regulators of filamentous growth, we compared the Mit1 ChIP data to the existing high-resolution data for Ste12, Tec1, and Sok2 (Borneman et al. 2007b). We found that 91% (62/68, P = 2.59E-62) of the Mit1 bound intergenic regions were also bound by Sok2, 69% (47/68, P = 3.65E-44) were bound by Tec1, and 71% (48/68, P = 1.00E-46) by Ste12 (Figure 2C, Table S8, and File S1). This strong overlap among downstream targets further supports the conclusion that Mit1 is a central regulator of the filamentous growth program.

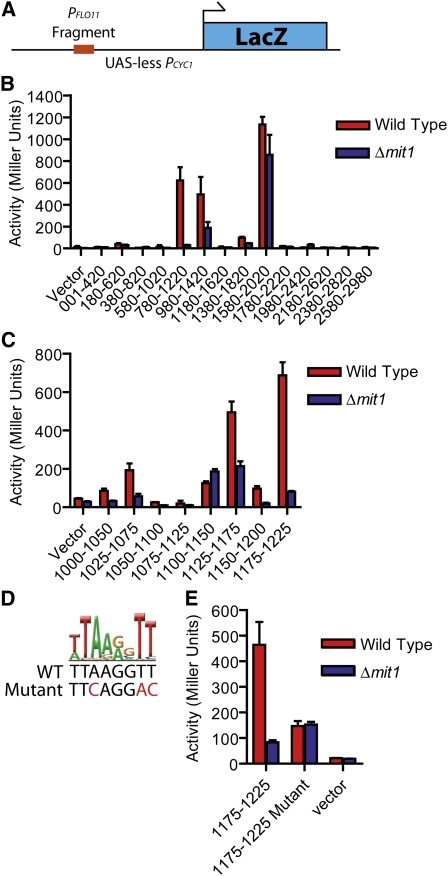

Mit1 acts on a specific motif within the FLO11 promoter

To test whether Mit1 association with DNA, as determined by ChIP, was functionally relevant, we analyzed Mit1’s binding to the promoter of the FLO11 gene in detail. To identify the minimal DNA sequence required for Mit1 to activate expression of FLO11, we utilized a set of constructs containing overlapping 440-bp fragments of the FLO11 promoter cloned into a PCYC1-LacZ plasmid construct lacking its native upstream activating sequence (Figure 3A). These plasmids were previously used to identify regions of the FLO11 upstream region required for activation by Ste12, Tec1, and Flo8 (Rupp et al. 1999). We transformed this plasmid set into both wild-type and Δmit1 haploid Σ2000 S. cerevisiae strains and identified two overlapping 440-bp fragments that possessed Mit1-dependent transcriptional activity (Figure 3B). The 240-bp overlap between these fragments is distinct from the sites of action of Ste12 and Tec1, includes the site of action of Flo8, and corresponds to the most highly enriched site for Mit1 binding in the ChIP experiment.

Figure 3 .

Mit1 acts on a discrete location within the FLO11 promoter corresponding to the Mit1/Wor1 DNA-binding motif. (A) Schematic of the UAS-less PCYC1 plasmid with a FLO11 promoter fragment used for the β-galactosidase activation assays. (B) Fragments (440 bp) of the FLO11 promoter were inserted into a UAS-less CYC1 promoter upstream of a LacZ reporter construct, as previously reported (Rupp et al. 1999). These plasmids were transformed into either wild-type haploid a cells (red) or Δmit1 haploid a cells (blue), and standard β-galactosidase assays were performed in selective SD media. β-Galactosidase units of activity (Miller units) are plotted on the y-axis, and fragments of the FLO11 promoter are indicated on the x-axis (numbers represent the position of individual fragments relative to the FLO11 start codon). (C) Fragments (50 bp) of the FLO11 promoter were inserted into the LacZ reporter plasmid and β-galactosidase activity was measured for strains grown under the same conditions as in B. Fragment 1175–1225 displayed the strongest activity, and this activity was Mit1 dependent. Axis labeling is as in B. (D and E) A sequence resembling the Mit1/Wor1 recognition motif (displayed as a logo) was identified in the 1175–1225 FLO11 promoter fragment. Three bases of this motif were mutated as shown (red), and the corresponding plasmid (“1175–1225 Mutant”) exhibited reduced Mit1-dependent β-galactosidase activity when transformed into yeast. Axis labeling is as in B. Error bars in B, C, and E represent the standard deviation from two or three experiments.

To further refine a DNA element required for activation by Mit1, we generated a series of plasmids containing overlapping 50-bp fragments of this 240-bp region. Two fragments showed Mit1-dependent transcriptional activation, corresponding to 1025–1075 bp and 1175–1225 bp upstream of the start codon (Figure 3C). Both fragments contained a high-scoring DNA motif recognized by the C. albicans ortholog Wor1 (Lohse et al. 2010). To test whether this motif was needed for Mit1-dependent activation, we changed three critical nucleotides in the central core of this motif in the 1175–1225 fragment (Figure 3D). When assayed in the reporter system described above, these mutations reduced Mit1-dependent transcriptional activity (Figure 3E), revealing that the motif is recognized by Mit1. Moreover, these results indicate that Mit1 functions as an activator of transcription, at least in this minimal system.

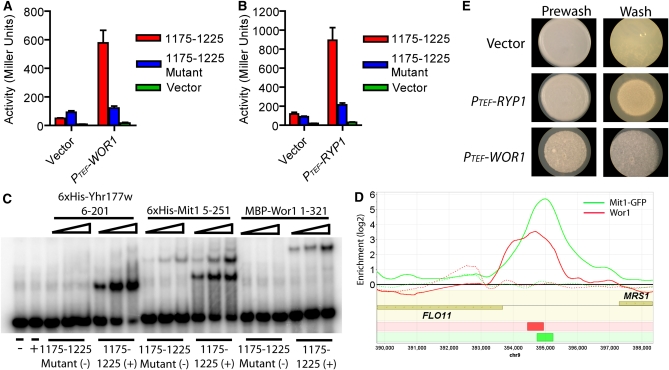

Mit1, Wor1, and Ryp1 recognize the same DNA sequence

To further test the idea that Mit1 and Wor1 can recognize the same DNA sequence, we ectopically expressed C. albicans WOR1 in a Δmit1Δyhr177w S. cerevisiae strain. Wor1 activated transcription from the 1175–1225 sequence of the FLO11 promoter to high levels (Figure 4A), and point mutations in the binding site destroyed Wor1-dependent activation. Similar results were obtained for H. capsulatum Ryp1 (Figure 4B). Furthermore, ectopic expression of either WOR1 or RYP1 induced haploid invasive growth in the absence of MIT1 and YHR177W (Figure S2).

Figure 4 .

DNA binding and activation functions are conserved among S. cerevisiae Mit1, C. albicans Wor1, and H. capsulatum Ryp1. (A and B) Reporter plasmids carrying a functional upstream 1175–1225 FLO11 promoter fragment (1175–1225, red), the nonfunctional mutated version of the fragment (1175–1225 mutant, blue), or no insert (vector, green) were cotransformed with a plasmid containing the TEF promoter driving an empty vector, (A) C. albicans WOR1, or (B) H. capsulatum RYP1. Both PTEF-WOR1 and PTEF-RYP1 activate transcription from the wild-type but not the mutant FLO11 fragment-CYC1 construct. β-Galactosidase units of activity (Miller units) are plotted on the y-axis, and error bars in A and B represent the standard deviation from two or three experiments. (C) Yhr177w, Mit1, and Wor1 bind to the 1175–1225 fragment from the FLO11 promoter, as monitored by gel shift assays. Mit1 (5–251 aa), Yhr177w (6–201 aa), and MBP-Wor1 (1–321 aa) were incubated with either the FLO11 1175–1225 promoter fragment (1175–1225, +) or the FLO11 1175–1225 mutant fragment (1175–1225 mutant, −). All three proteins bind to the FLO11 1175–1225 promoter fragment but not to the mutated fragment, indicating that the binding of Mit1, Yhr177w, and Wor1 to the FLO11 promoter is sequence specific. Yhr177w and Mit1 concentrations range from 0.5 to 4 nM, and MBP-Wor1 concentrations range from 2 to 8 nM. (D) A ChIP-chip plot showing ectopically expressed Wor1 associating with the FLO11 promoter in vivo. Wor1 was immunoprecipitated from a Δmit1Δyhr177w strain carrying the PTEF-WOR1 plasmid (solid red line), and the control is a Δmit1Δyhr177w strain carrying PTEF-vector plasmid (dashed red line). ChIP data for the Mit1-GFP experiments in a Mit1-GFP strain (solid green line) or in a control strain lacking GFP (dashed green line) are included for comparison. The red box in the bottom track represents a called Wor1 binding site and the green box represents a called Mit1 binding site. Data were visualized using Mochiview 1.45, with the x-axis representing the genomic location and the y-axis representing log2 enrichment. (E) Ectopic expression of WOR1 or RYP1 induces invasive growth on SD media. a/α diploid Σ2000 cells were spotted on SD agar, grown for 2 days at 30°, and then washed under a stream of water. Pre- (left) and post- (right) wash images are shown.

Finally, we directly showed that Wor1, Mit1, and Yhr177w bind to the S. cerevisiae Mit1 site by performing electrophoretic mobility shift experiments with Escherichia coli purified MBP-Wor1 (1–321 aa), 6× His-Mit1 (5–251 aa), and 6× His-Yhr177w (6–201 aa). All three proteins bind the 1175- to 1225-bp fragment of the FLO11 promoter, and this binding is lost when the Mit1 motif is mutated (Figure 4C).

The DNA-binding experiments described above predict that Wor1, if ectopically expressed in S. cerevisiae, should occupy at least some of the genomic sites normally occupied by Mit1. To test this idea, we expressed WOR1 (under control of the TEF promoter) in the Δmit1Δyhr177w S. cerevisiae strain and, through full genome chromatin immunoprecipitation, found that it associates not only with the FLO11 promoter, but also with at least six additional Mit1 target upstream regions (Figure 4D, Table S9, Table S10, File S1, and File S5). The levels of enrichment were lower for the Wor1 experiment than for the Mit1 experiment, so we cannot state with precision the actual overlap of target genes; however, it appears very high.

Thus, the DNA-binding specificity of the WOPR domain in Mit1, Ryp1, and Wor1 has been preserved over at least 600 million years. Such a result is not unprecedented; for example, the DNA-binding specificity of a MADS-box protein (Mcm1) has remained constant over this same evolutionary distance (Tuch et al. 2008). On the other hand, there are examples where DNA-binding specificity of a conserved regulator has changed significantly over much shorter evolutionary time periods (Baker et al. 2011).

Comparison of Mit1 and Wor1 target genes

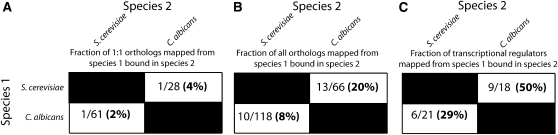

Given that Mit1, Wor1, and Ryp1 recognize the same DNA sequence, it seemed unlikely that the different cellular phenotypes governed by these orthologs could be explained by a major divergence in their protein function. Instead, we hypothesized that the sets of genes controlled by each regulator have changed significantly during the ∼600 million years since they diverged from a common ancestor (Taylor and Berbee 2006). We tested this idea in two ways. First, the ectopic expression of either WOR1 or RYP1 in S. cerevisiae activates the pseudohyphal growth program (Figure 4E, Figure S2), consistent with the idea that the biochemical functions of Wor1, Ryp1, and Mit1 have remained largely conserved. Second, where possible, we mapped the 94 Mit1 target genes in S. cerevisiae (as determined by ChIP-chip) to their C. albicans orthogroups (see Materials and Methods). Sixty-six of the S. cerevisiae Mit1 target genes had at least one ortholog in C. albicans, but only 13 of these were also bound by Wor1 in C. albicans (Zordan et al. 2007) (Figure 5, Table 1, Table S11, Table S12, and File S1). We performed the same analysis in the opposite direction—mapping Wor1 targets to S. cerevisiae orthologs—and, as expected, found similar results (Figure 5, Table 1, Table S11, Table S12, and File S1). These observations are consistent with the high level of rewiring documented in the ascomycete lineage (Borneman et al. 2007a; Tuch et al. 2008) and indicate that the Wor1 and Mit1 circuits have undergone considerable diversification.

Figure 5 .

A comparison of the Mit1 regulon in S. cerevisiae to the Wor1 regulon in C. albicans indicates there is a small conserved set of orthologous genes that code for transcriptional regulators that are bound by both Mit1 and Wor1. (A–C) The number of Mit1- or Wor1-bound genes in species 1 that are also bound in species 2, as a fraction of the total genes bound in species 1 that can be mapped to orthologs in species 2 when (A) only 1:1 orthologous relationships are considered, (B) all orthologous relationships (i.e., 1:1, 2:1, 3:5) are considered, or (C) only Mit1- or Wor1-bound genes that encode sequence-specific DNA-binding proteins are considered.

Table 1 . Conserved targets of the Mit1/Wor1 regulon.

| S. cerevisiae bound target | C. albicans bound target | Transcriptional regulator | Gene description in S. cerevisiae | Gene description in C. albicans |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIT1 | WOR1 | Yes | Master regulator of pseudohyphal growth | Master regulator of the white–opaque switch |

| YHR177w | WOR1 | Yes | No known function | Master regulator of the white–opaque switch |

| TOS8 | CUP9 | Yes | Bound by all seven pseudohyphal growth regulators | Repressed upon yeast–hyphal transition |

| CUP9 | CUP9 | Yes | Regulator of peptide transporters | Repressed upon yeast–hyphal transition |

| PHD1 | EFG1 | Yes | Overexpression enhances pseudohyphal growth | Regulates white–opaque switch, filamentation, cell wall-related genes |

| SOK2 | EFG1 | Yes | Deletion enhances pseudohyphal growth, positively regulates meiosis | Regulates white–opaque switch, filamentation, cell wall–related genes |

| ROX1 | RFG1 | Yes | Repressor of hypoxic genes, required for pseudohyphal growth | Repressor of filamentous growth |

| GAT2 | GAT2 | Yes | Repressed by leucine | Deletion has severe filamentation defects |

| RSF2 | orf19.5026 | Yes | Involved in glycerol-based growth | No known function |

| CLN1 | HGC1 | No | G1 cyclin, late G1-specific expression promotes S phase | Hypha-specific G1 expression, required for hyphal growth |

| SPS4 | orf19.7502 | No | Induced during sporulation | No known function, Hap43 induced |

| SUN4 | SUN41 | No | Glucanase possibly involved in cell septation | Cell wall glycosidase, hyphal induced, Efg1 regulated, involved in biofilm formation and cell separation |

| UTH1 | SIM1 | No | Mitochondrial outer membrane and cell wall localized SUN family member involved in cell wall biogenesis | Putative adhesin-like protein involved in cell wall maintenance |

Although the overlap between these circuits is small, it is not likely to have occurred by chance (P = 1 × 10−6 by bootstrap analysis, see Materials and Methods), indicating that a small portion of an ancestral circuit has likely been preserved in C. albicans and S. cerevisiae (Figure 5, Figure S3, Table 1, Table S11, and Table S12). Nine of the 13 overlapping targets are transcriptional regulators (Table 1). While transcriptional regulators are enriched overall in the Mit1-bound set, this bias for conserved transcription factors in the overlap of the two data sets remains significant [P = 0.008, Fisher’s exact test (two-tailed)]. Seven of the 9 transcription factors that are conserved targets of Mit1/Wor1 are also targets of all six core members of the core filamentous growth network in S. cerevisiae (Monteiro et al. 2008), suggesting that a network of interactions among transcriptional regulators has been conserved across hundreds of millions of years of evolution while the “downstream” target genes of these regulators have rapidly moved in and out of the regulons.

Discussion

A great deal of evolutionary diversity (nominally >1 billion years) is embodied in the fungal kingdom. On a phenotypic level, this diversity can be easily visualized in the many different types of morphological transformations observed across fungal species. In this article, we consider three species of fungi—S. cerevisiae (baker’s yeast), C. albicans (the major human fungal pathogen), and H. capsulatum (the cause of histoplasmosis)—each of which undergoes a specialized morphological program. Despite the fact that the morphologic transitions considered are different from one species to the next (pseudohyphal growth in S. cerevisiae, white–opaque switching in C. albicans, and the mycelia to yeast transition in H. capsulatum), an orthologous regulator (Mit1 from S. cerevisiae, Wor1 from C. albicans, and Ryp1 from H. capsulatum) is a major regulator of each. The three proteins all contain a WOPR domain, a 200-aa region that folds into a sequence-specific DNA-binding domain. We show that, despite an estimated 600 million years of divergence, these orthologs bind to and activate transcription from the same DNA sequence motif. We also show that Wor1 (from C. albicans) and Ryp1 (from H. capsulatum) can drive the pseudohyphal growth of S. cerevisiae when overexpressed in that species. We conclude from our analysis that Mit1, Wor1, and Ryp1 are clear orthologs, that they retain their ancestral DNA-binding specificity, that they can activate transcription, and that, in some cases, the protein from one species can substitute for its ortholog in another species.

Although Mit1, Wor1, and Ryp1 appear to be similar biochemically, they each control a distinctive type of morphological change in their respective species. We hypothesized that evolutionary changes in the genes under control of each regulator—rather than changes to the regulators themselves—are the major contributor to the different physiological responses. We tested this idea directly by considering genes bound by each regulator in each species. ChIP-chip and transcriptional profiling data are available for both Wor1 in C. albicans (Lan et al. 2002; Tsong et al. 2003; Zordan et al. 2007; Tuch et al. 2010) and Ryp1 in H. capsulatum (A. Sil, unpublished data) and, in this article, we generated comparable data for Mit1 in S. cerevisiae. We found that the set of genes bound by an ortholog in one species is considerably different from the set in another species. We were able to carry out a meaningful comparison between S. cerevisiae and C. albicans orthologs and found that—of genes controlled by Mit1 in S. cerevisiae that had a clear ortholog in C. albicans—only 20% were controlled by Wor1 in C. albicans. As described in Results, the overlapping target genes are made up predominately of other transcriptional regulators, indicating that a portion of an ancestral circuit where Wor1/Mit1 controlled other transcriptional regulators was retained in both S. cerevisiae and C. albicans. However, the majority of the orthologous target genes regulated in one species are not regulated by the ortholog in the other species. We suggest that this diversification of target genes explains, in part, why the Mit1, Wor1, and Ryp1 proteins have retained many ancestral characteristics, yet they regulate very different morphological transitions. It also explains why ectopic overexpression of WOR1 (from C. albicans) or RYP1 (from H. capsulatum) in S. cerevisiae drives the S. cerevisiae pseudohyphal growth program rather than aspects of the morphological program specific to the species of origin.

In conclusion, this article shows that three orthologous regulators (one from each of three fungal species) possess very similar biological properties (e.g., they recognize the same DNA sequence and activate transcription), yet they are master regulators of three distinct morphological transitions. We suggest, in accord with other examples (Prud’homme et al. 2007; Carroll 2008; Tuch et al. 2008), that changes in cis-regulatory sequences within target gene promoters are, at least in part, responsible for the different phenotypic outputs in different species produced by orthologous and biochemically similar regulators.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Hiten Madhani, Greg Prelich, and Jeff Cox for plasmids, strains, and experimental advice. In addition, the authors thank Eric Summers and Gerald Fink for sharing unpublished information about the Δmit1 phenotype. The authors thank Aaron Hernday, Christian Perez, and Clarissa Nobile for help with data analysis and valuable comments on this manuscript. Work of the authors was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (R01 AI49187). C.W.C. was supported by a Genentech Graduate Student Fellowship.

Footnotes

Communicating editor: K. M. Arndt

Literature Cited

- Anderson J. M., Soll D. R., 1987. Unique phenotype of opaque cells in the white-opaque transition of Candida albicans. J. Bacteriol. 169: 5579–5588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker C. R., Tuch B. B., Johnson A. D., 2011. Extensive DNA-binding specificity divergence of a conserved transcription regulator. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108: 7493–7498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borneman A. R., Leigh-Bell J. A., Yu H., Bertone P., Gerstein M., et al. , 2006. Target hub proteins serve as master regulators of development in yeast. Genes Dev. 20: 435–438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borneman A. R., Gianoulis T. A., Zhang Z. D., Yu H., Rozowsky J., et al. , 2007a Divergence of transcription factor binding sites across related yeast species. Science 317: 815–819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borneman A. R., Zhang Z. D., Rozowsky J., Seringhaus M. R., Gerstein M., et al. , 2007b Transcription factor binding site identification in yeast: a comparison of high-density oligonucleotide and PCR-based microarray platforms. Funct. Integr. Genomics 7: 335–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll S. B., 2008. Evo-devo and an expanding evolutionary synthesis: a genetic theory of morphological evolution. Cell 134: 25–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagiano M., Bauer F. F., Peretorius I. S., 2002. The sensing of nutritional status and the relationship to filamentous growth in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Yeast Res. 2: 433–470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger J., Wessels D., Lockhart S. R., Soll D. R., 2004. Release of a potent polymorphonuclear leukocyte chemoattractant is regulated by white-opaque switching in Candida albicans. Infect. Immun. 72: 667–677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimeno C. J., Ljungdahl P. O., Styles C. A., Fink G. R., 1992. Unipolar cell divisions in the yeast S. cerevisiae lead to filamentous growth: regulation by starvation and RAS. Cell 68: 1077–1090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S., Stamatoyannopoulos J. A., Bailey T. L., Noble W. S., 2007. Quantifying similarity between motifs. Genome Biol. 8: R24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie C., Fink G. R. (Editors), 1991. Guide to Yeast Genetics and Molecular Biology. Academic Press, San Diego [Google Scholar]

- Holbrook E. D., Rappleye C. A., 2008. Histoplasma capsulatum pathogenesis: making a lifestyle switch. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 11: 318–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homann O. R., Johnson A. D., 2010. MochiView: versatile software for genome browsing and DNA motif analysis. BMC Biol. 8: 49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang G., Wang H., Chou S., Nie X., Chen J., et al. , 2006. Bistable expression of WOR1, a master regulator of white-opaque switching in Candida albicans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103: 12813–12818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh W. K., Falvo J. V., Gerke L. C., Carroll A. S., Howson R. W., et al. , 2003. Global analysis of protein localization in budding yeast. Nature 425: 686–691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones G. M., Stalker J., Humphray S., West A., Cox T., et al. , 2008. A systematic library for comprehensive overexpression screens in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nat. Methods 5: 239–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadosh D., Johnson A. D., 2001. Rfg1, a protein related to the Saccharomyces cerevisiae hypoxic regulator Rox1, controls filamentous growth and virulence in Candida albicans. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21: 2496–2505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvaal C. A., Srikantha T., Soll D. R., 1997. Misexpression of the white-phase-specific gene WH11 in the opaque phase of Candida albicans affects switching and virulence. Infect. Immun. 65: 4468–4475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvaal C., Lachke S. A., Srikantha T., Daniels K., McCoy J., et al. , 1999. Misexpression of the opaque-phase-specific gene PEP1 (SAP1) in the white phase of Candida albicans confers increased virulence in a mouse model of cutaneous infection. Infect. Immun. 67: 6652–6662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachke S. A., Lockhart S. R., Daniels K. J., Soll D. R., 2003. Skin facilitates Candida albicans mating. Infect. Immun. 71: 4970–4976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan C. Y., Newport G., Murillo L. A., Jones T., Scherer S., et al. , 2002. Metabolic specialization associated with phenotypic switching in Candida albicans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99: 14907–14912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F., Palecek S. P., 2005. Identification of Candida albicans genes that induce Saccharomyces cerevisiae cell adhesion and morphogenesis. Biotechnol. Prog. 21: 1601–1609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Styles C. A., Fink G. R., 1996. Saccharomyces cerevisiae S288C has a mutation in FLO8, a gene required for filamentous growth. Genetics 144: 967–978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo W. S., Dranginis A. M., 1998. The cell surface flocculin Flo11 is required for pseudohyphae formation and invasion by Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 9: 161–171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohse M. B., Johnson A. D., 2008. Differential phagocytosis of white vs. opaque Candida albicans by Drosophila and mouse phagocytes. PLoS ONE 3: e1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohse M. B., Johnson A. D., 2009. White-opaque switching in Candida albicans. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 12: 650–654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohse M. B., Zordan R. E., Cain C. W., Johnson A. D., 2010. Distinct class of DNA-binding domains is exemplified by a master regulator of phenotypic switching in Candida albicans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107: 14105–14110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longtine M. S., McKenzie A., Demarini D. J., Shah N. G., Wach A., et al. , 1998. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 14: 953–961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller M. G., Johnson A. D., 2002. White-opaque switching in Candida albicans is controlled by mating-type locus homeodomain proteins and allows efficient mating. Cell 110: 293–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro P. T., Mendes N. D., Teixeira M. C., d’Orey S., Tenreiro S., et al. , 2008. YEASTRACT-DISCOVERER: new tools to improve the analysis of transcriptional regulatory associations in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 36: D132–D136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mumberg D., Müller R., Funk M., 1995. Yeast vectors for the controlled expression of heterologous proteins in different genetic backgrounds. Gene 156: 119–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen V. Q., Sil A., 2008. Temperature-induced switch to the pathogenic yeast form of Histoplasma capsulatum requires Ryp1, a conserved transcriptional regulator. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105: 4880–4885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobile C. J., Nett J. E., Hernday A. D., Homann O. R., Deneault J. S., et al. , 2009. Biofilm matrix regulation by Candida albicans Zap1. PLoS Biol. 7: e1000133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prud’homme B., Gompel N., Carroll S. B., 2007. Emerging principles of regulatory evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 8605–8612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rikkerink E. H., Magee B. B., Magee P. T., 1988. Opaque-white phenotype transition: a programmed morphological transition in Candida albicans. J. Bacteriol. 170: 895–899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rupp S., 2002. LacZ assays in yeast. Methods Enzymol. 350: 112–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rupp S., Summers E., Lo H., Madhani H., Fink G., 1999. MAP kinase and cAMP filamentation signaling pathways converge on the unusually large promoter of the yeast FLO11 gene. EMBO J. 18: 1257–1269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweizer A., Rupp S., Taylor B. N., Röllinghoff M., Schröppel K., 2000. The TEA/ATTS transcription factor CaTec1p regulates hyphal development and virulence in Candida albicans. Mol. Microbiol. 38: 435–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slutsky B., Staebell M., Anderson J., Risen L., Pfaller M., et al. , 1987. “White-opaque transition”: a second high-frequency switching system in Candida albicans. J. Bacteriol. 169: 189–197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soll D. R., 2009. Why does Candida albicans switch? FEMS Yeast Res. 9: 973–989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srikantha T., Borneman A. R., Daniels K. J., Pujol C., Wu W., et al. , 2006. TOS9 regulates white-opaque switching in Candida albicans. Eukaryot. Cell 5: 1674–1687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor J. W., Berbee M. L., 2006. Dating divergences in the Fungal Tree of Life: review and new analyses. Mycologia 98: 838–849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsong A. E., Miller M. G., Raisner R. M., Johnson A. D., 2003. Evolution of a combinatorial transcriptional circuit: a case study in yeasts. Cell 115: 389–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuch B. B., Galgoczy D. J., Hernday A. D., Li H., Johnson A. D., 2008. The evolution of combinatorial gene regulation in fungi. PLoS Biol. 6: e38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuch B. B., Mitrovich Q. M., Homann O. R., Hernday A. D., Monighetti C. K., et al. , 2010. The transcriptomes of two heritable cell types illuminate the circuit governing their differentiation. PLoS Genet. 6: e1001070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wapinski I., Pfeffer A., Friedman N., Regev A., 2007. Natural history and evolutionary principles of gene duplication in fungi. Nature 449: 54–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods J. P., 2002. Histoplasma capsulatum molecular genetics, pathogenesis, and responsiveness to its environment. Fungal Genet. Biol. 35: 81–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zordan R. E., Galgoczy D. J., Johnson A. D., 2006. Epigenetic properties of white-opaque switching in Candida albicans are based on a self-sustaining transcriptional feedback loop. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103: 12807–12812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zordan R. E., Miller M. G., Galgoczy D. J., Tuch B. B., Johnson A. D., 2007. Interlocking transcriptional feedback loops control white-opaque switching in Candida albicans. PLoS Biol. 5: e256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]