Abstract

Two defining functional features of ion channels are ion selectivity and channel gating. Ion selectivity is generally considered an immutable property of the open channel structure, whereas gating involves transitions between open and closed channel states typically without changes in ion selectivity 1. In store-operated Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ (CRAC) channels, the molecular mechanism of channel gating by the CRAC channel activator, STIM1 (stromal interaction molecule 1) remains unknown. CRAC channels are distinguished by an extraordinarily high Ca2+ selectivity and are instrumental in generating sustained [Ca2+]i elevations necessary for gene expression and effector function in many eukaryotic cells 2. Here, we probed the central features of the STIM1 gating mechanism in the CRAC channel protein, Orai1, and identified V102, a residue located in the extracellular region of the pore, as a candidate for the channel gate. Mutations at V102 produced constitutively active CRAC channels that were open even in the absence of STIM1. Unexpectedly, although STIM1-free V102 mutant channels were not Ca2+-selective, their Ca2+ selectivity was dose-dependently boosted by interactions with STIM1. Similar enhancement of Ca2+ selectivity also occurred in wild-type (WT) Orai1 channels by increasing the number of STIM1 activation domains directly tethered to Orai1 channels. Thus, exquisite Ca2+ selectivity is not an intrinsic property of CRAC channels, but rather a tunable feature bestowed on otherwise non-selective Orai1 channels by STIM1. Our results demonstrate that STIM1-mediated gating of CRAC channels occurs through an unusual mechanism wherein permeation and gating are closely coupled.

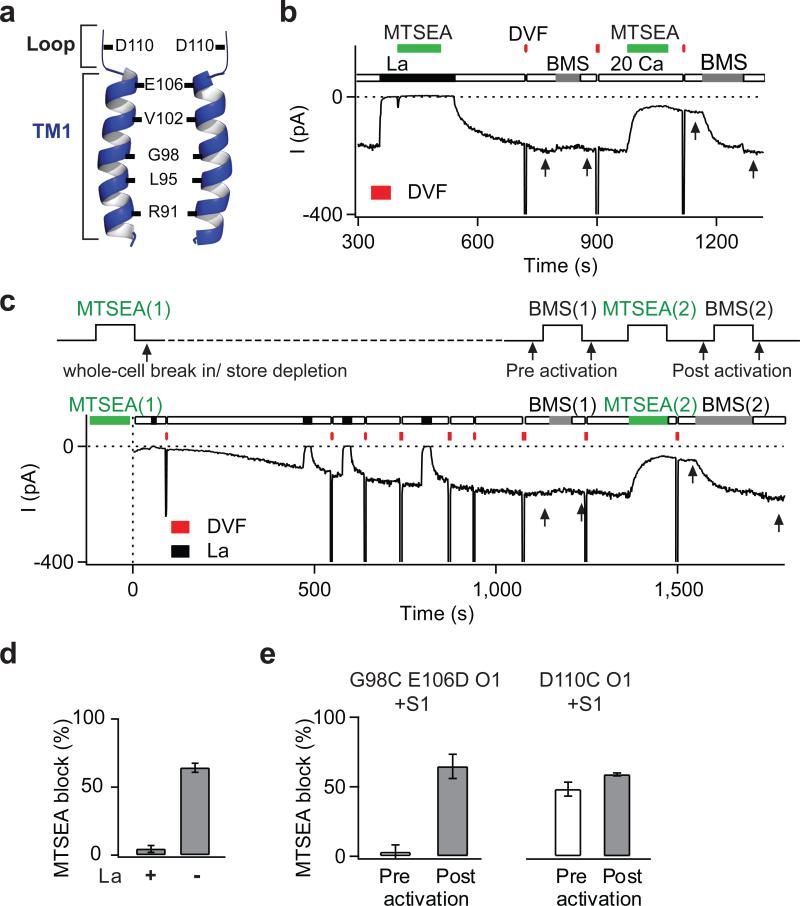

Functional CRAC channels are tetramers of Orai1 subunits 3-5, with the pore flanked by residues of the first transmembrane domain (TM1) of each subunit 6,7(Fig. 1a). To localize the gate region that governs STIM1-dependent activation, we mutated individual pore-lining residues to Cys and analyzed state-dependent differences in the sensitivity of mutant channels to methanethiosulfonate (MTS) Cys-reactive reagents 6,8. Because the unusually narrow CRAC channel pore 9,10 prevents entry of the relatively large MTS reagents 6, we performed these studies in the E106D Orai1 mutant, which exhibits a wider pore, yet maintains store-dependent activation 10. In this background, several TM1 pore-lining residues including V102C and G98C became accessible to the small MTS reagent, MTSEA, with G98C exhibiting particularly strong sensitivity to this reagent (Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. 1). Inhibition of G98C by MTSEA could be protected by La3+ (Fig. 1b,d), which blocks CRAC channels by binding to residues in the outer vestibule 6, consistent with modification of G98C occurring from within the pore.

Figure 1. State-dependent accessibility of pore-lining residues localizes the activation gate to the extracellular TM1 region.

a, Schematic representation of the key pore-lining residues in TM1 6. b, MTSEA modification of G98C is protected by La3+. A HEK293 cell co-expressing G98C E106D Orai1 and STIM1 was exposed to two applications of MTSEA (100 μM), the first in the presence of La3+ (100 μM), and the second following washout of La3+. Periodic applications of a divalent free (DVF) solution facilitated washout of La3+. MTSEA inhibition was quantified by the relief of block induced by BMS (5 mM) (arrows). c, State-dependent modification of G98C. MTSEA (200 μM) was applied for 120 s to resting cells, then washed off. Following whole-cell break in, ICRAC was activated by passive store depletion by dialyzing in BAPTA. BMS was applied to examine relief from MTSEA blockade (arrows). A second application of MTSEA and BMS provide a measure of blockade in open channels. A DVF solution was periodically applied to monitor Na+-ICRAC. d, Summary of MTSEA blockade of open G98C E106D Orai1 in the presence and absence of La3+. e, Summary of blockade of G98C E106D and D110C Orai1 by MTSEA in closed and open channels. Values are mean ± s.e.m.

To determine differences in MTSEA accessibility between closed and open channels, we quantified relief of MTSEA blockade elicited by the reducing agent, bis(2-mercaptoethylsulfone) (BMS) 6. Resting cells were exposed to MTSEA for 100-120 s and subsequently, CRAC current (ICRAC) was activated by passive store depletion (Fig. 1c). These experiments indicated that modification of G98C was profoundly state-dependent, with no modification occurring in closed channels (Fig. 1c,e). By contrast, D110C, a pore-lining residue located in the outer vestibule, was modified to similar extents in both closed and open states (Fig. 1e). The most straightforward explanation for this result is that the closed channel conformation prevents access of MTSEA to G98C, suggesting that the gate is located external to G98, but below D110. As the key pore-lining TM1 residues in this region are E106 and V102, the gated access of G98C implicates these residues as potential candidates for the gate. E106 controls Ca2+ selectivity 11-13 and is not thought to regulate store-operated gating 10, leaving V102 as a residue worthy of further scrutiny.

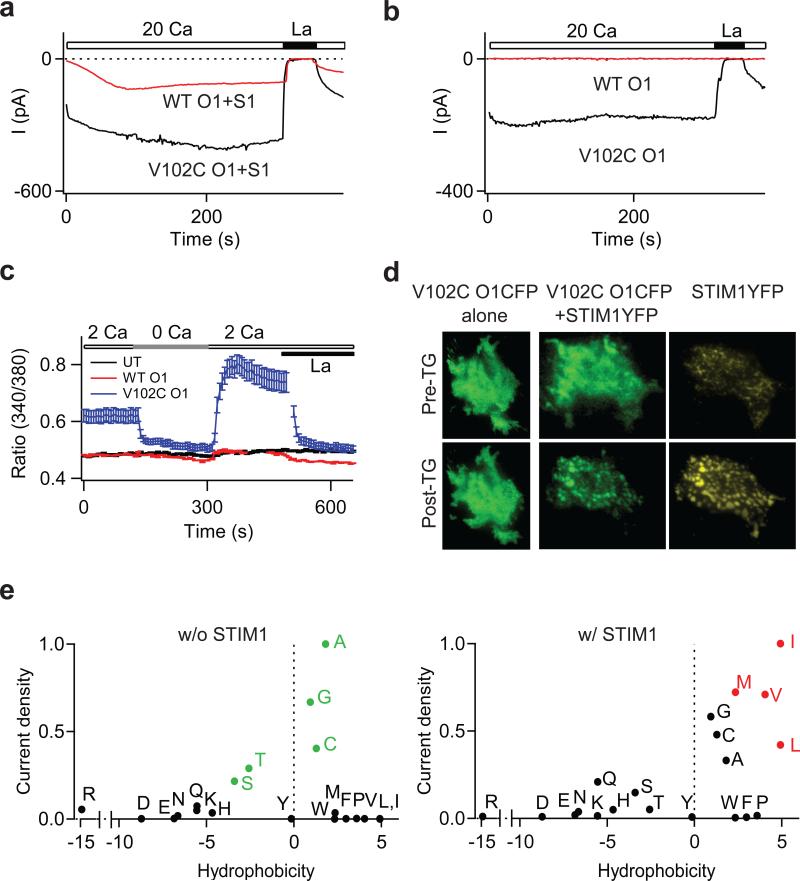

Previous reports suggest that V102 is very close to the central symmetry axis of the channel 6,7, i.e., in a narrow constriction of the pore. If V102 is a component of the gating mechanism, mutations at this locus would be predicted to destabilize channel gating. Consistent with this possibility, a Cys mutation of V102 eliminated store-dependent gating. Cells expressing V102C Orai1 and STIM1 displayed a large standing ICRAC upon whole-cell break-in (Fig. 2a). Moreover, resting cells exhibited constitutive Ca2+ entry and activation of the Ca2+-dependent transcription factor, NFAT (Supplementary Fig. 2), indicating that V102C Orai1 channels are constitutively active.

Figure 2. Mutations at V102 cause STIM1-independent constitutive Orai1 activation.

a, Time course of the development of ICRAC in cells expressing WT or V102C Orai1 and STIM1 following whole-cell break-in. Intracellular Ca2+ stores were depleted by dialyzing cells with 8 mM BAPTA. b, V102C Orai1 currents are constitutively active in the absence of STIM1 co-expression. c, [Ca2+]i measurements in HEK293 cells expressing the indicated Orai1 constructs in the absence of STIM1. WT: wild-type. UT: untransfected. d, Localization of V102C Orai1-CFP before, and following ER Ca2+ store depletion in the absence (left) or presence (right) of STIM1-YFP. e, Mutational analysis of V102. Normalized current densities of V102 substitutions plotted against the solvation energies of the substituted amino acids 30 in the presence or absence of STIM1 co-expression. Currents were normalized to the mutant yielding maximal current density for each condition (Ala for STIM1-free cells and Ile in STIM1-co-expressing cells). Green points in the top graph highlight residues yielding large constitutively active currents in the absence of STIM1. Red points in the lower graph highlight residues that are not constitutively active, but require STIM1 for activation.

Several lines of evidence indicated that the constitutive activation of V102C Orai1 is STIM1-independent. Large La3+-sensitive standing currents were observed in cells expressing V102C Orai1 alone (Fig. 2b). Further, Ca2+ imaging and NFAT activation experiments revealed constitutive Ca2+ entry in these cells (Fig 2c and Supplementary Fig 2c). Recent evidence indicates that STIM1 drives the redistribution of Orai1 into discrete puncta following ER store depletion 2. However, when expressed alone, V102C Orai1 remained diffusely distributed (Fig 2d). Moreover, ICRAC in these cells did not show Ca2+-dependent fast inactivation (CDI) (Supplementary Fig. 3). Because puncta formation and CDI require STIM1 14-16, these results indicate that when over-expressed alone, the mutant channels are functionally free of STIM1. Additionally, knockdown of endogenous STIM1 in HEK293 cells did not affect the constitutive V102C current (Supplementary Table 1). However, when V102C Orai1 was co-expressed with STIM1, puncta formation, interaction with STIM1, and CDI were indistinguishable from the behavior of WT Orai1 (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Figs. 3&4). Additional analyses indicated that introducing the mutations, E106A or R91W, which abrogate store-operated Orai1 activity 11,12,17 strongly diminished V102C Orai1 currents (Supplementary Fig. 5a), indicating that these residues are essential for both store-operated and constitutive activation modes of Orai1. Mutation of the equivalent residue in Orai3 (V77C) also resulted in a STIM1-independent activation phenotype similar to that seen in V102C Orai1 (Supplementary Figure 6). Together, these results indicate that the V102C mutation destabilizes the channel gate, resulting in STIM1-independent constitutive Orai1 activation.

Many ion channels including nAChRs and MscL channels are reported to employ hydrophobic residues (Leu, Val, and Ile) as gates to inhibit the flux of hydrated ions 18,19,20 To explore the possibility that V102 comprises a hydrophobic gate in Orai1, we investigated the side-chain dependence of constitutive activation at this position. We observed constitutive activity with several mildly hydrophobic and polar substitutions, including Cys, Gly, Ala, Ser and Thr (Fig. 2e). Conversely, substitutions to the highly hydrophobic amino acids Leu, Ile, and Met resulted in only STIM1-dependent activation, as seen in WT Orai1. Large hydrophobic residues such as Trp, Tyr, and Phe diminished both constitutive and STIM1-induced currents, as expected for a position in a narrow region of the pore 6,7(Supplementary Fig. 5b). Substitutions to extremely polar residues such as Glu, Asp, Lys, and Arg resulted in non-functional channels with or without STIM1, likely due to secondary effects of these mutations on the nearby selectivity filter at E106. Despite these deviations, however, the overall pattern is consistent with the hypothesis that V102 comprises a hydrophobic gate, with less hydrophobic residues producing a leaky gate.

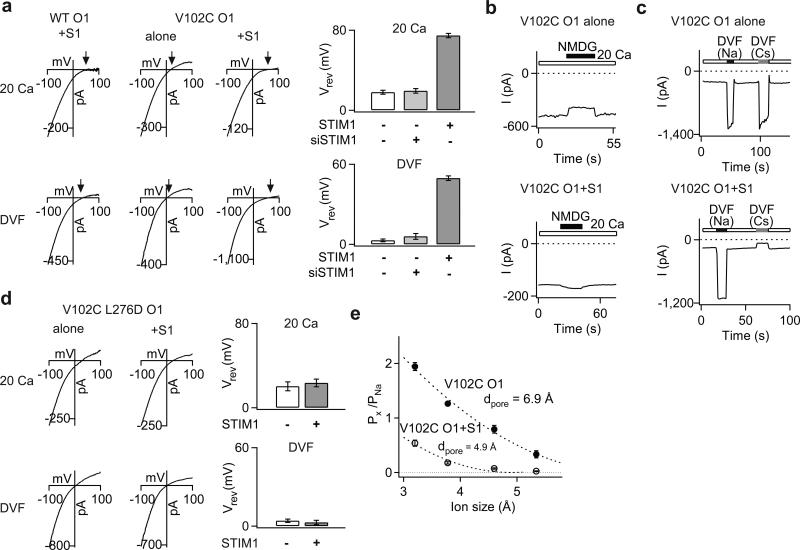

CRAC channels are extraordinarily Ca2+ selective and poorly permeable to the large monovalent cation, Cs+. However, the ion selectivity of STIM1-free V102C Orai1 channels differed from WT Orai1 channels in these respects. STIM1-free V102C Orai1 channels displayed significantly lower Ca2+ permeability, as evidenced by the left-shifted reversal potentials of mutant Ca2+ currents (Fig. 3a). Consistent with this interpretation, replacement of extracellular Na+ with NMDG+, an impermeant ion, revealed significant Na+ conduction in these channels (Fig. 3b). Direct estimates of fractional Ca2+ currents using fluo-4 indicated that V102C Orai1 conducts only 36% of the Ca2+ carried by WT Orai1 in 20 mM Ca2+ (Supplementary Fig. 7a). Additionally, unlike WT channels, STIM1-free V102C channels were highly permeable to the large monovalent cation, Cs+ (Fig. 3a-c, Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 3. STIM1 regulates ion selectivity of constitutively active V102C Orai1 channels.

a, Current-voltage (I-V) relationships of V102C Orai1 currents in 20 mM Ca2+ and DVF Ringer's solutions. Arrows emphasize the reversal potential (Vrev) in each case. The bar graphs (right) summarize (mean±sem) Vrev of V102C Orai1 currents in the presence or absence of STIM1. b, Effects of substituting extracellular Na+ with NMDG+ on V102C Orai1 currents in the absence or presence of STIM1. c, effects of replacing the standard extracellular Ringer's solution with Na+- or Cs+-based DVF solutions. In the absence of STIM1, large Cs+ currents are seen in V102C Orai1 channels. By contrast, no Cs+ conduction is observed in the presence of STIM1. d, I-V relationship of currents in the V102C L276D Orai1 double mutant in the presence or absence of STIM1. The bar graphs summarize the Vrev values (mean±sem) of this mutant in the presence or absence of STIM1. e, Relative permeabilities of V102C Orai1 channels to different organic monovalent cations is plotted against the size of each cation in the presence or absence of STIM1. Dotted lines are fits to the hydrodynamic relationship. Values of dpore estimated from the fits are 4.9 Å for V102C Orai1 + STIM1 channels and 6.9 Å for V102C Orai1 channels.

Unexpectedly, co-expressing exogenous STIM1 together with V102C Orai1 enhanced the Ca2+ permeability and lowered the Cs+ permeability of V102C Orai1, effectively correcting its aberrant ion selectivity (Fig 3a-c). STIM1 also modified permeation of V102C Orai1 for Ba2+ and Sr2+ (Supplementary Fig 7b). Modification of ion selectivity by STIM1 was not unique to V102C Orai1, but occurred in all constitutively active V102x mutants (Supplementary Table 1). These changes in ion selectivity required direct STIM1-Orai1 interactions, as modification of V102C Orai1 ion selectivity was nullified in the V102C L276D Orai1 double mutant (Fig. 3d), in which STIM1-Orai1 binding was impaired (Supplementary Fig. 4b,c) 21. STIM1-free and STIM1-bound V102C channels also displayed very different minimal pore widths (Fig. 3e), directly demonstrating that STIM1 alters the pore structure of V102C channels. Further analyses, using concatenated Orai1 dimers (described in the supplementary text), indicated that the subunit stoichiometry of STIM1-free and STIM1-bound mutant channels are identical, arguing that their distinct permeation properties are due to different pore structures of fully assembled, tetrameric channels rather than different subunit stoichiometries (Supplementary Fig. 8). Collectively, these results indicate that STIM1 binding modifies the structural features of the mutant channel pore, bestowing permeation properties classically associated with CRAC channels.

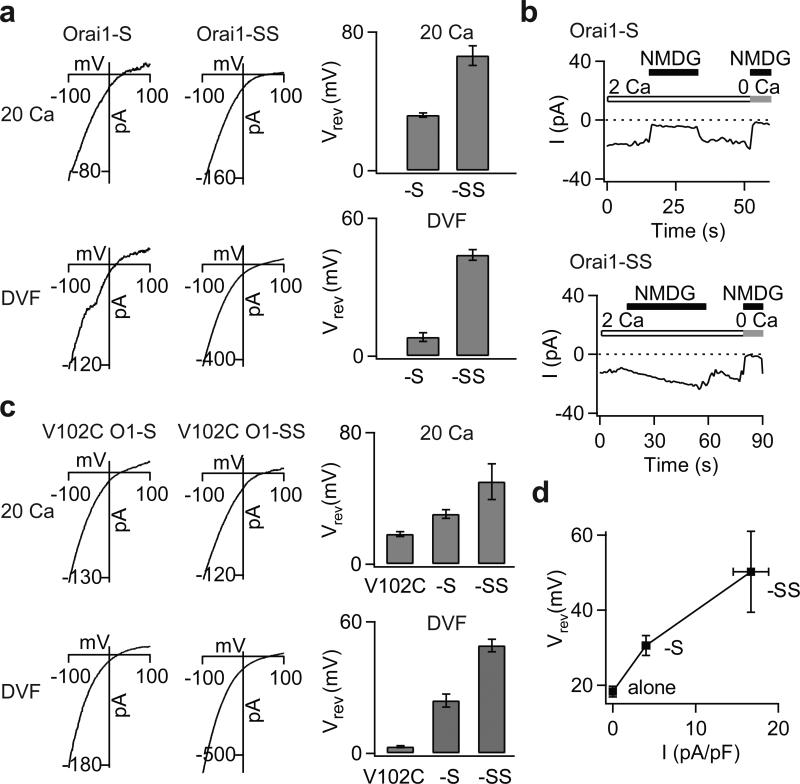

The normalization of ion selectivity of mutant channels by STIM1 suggests that their altered ion selectivity in the absence of STIM1 is not merely a byproduct of the mutations, but rather indicative of a native intermediate activation state not readily seen in WT channels due to a closed gate. Recent studies indicate that Orai1 channels are activated in a non-linear and cooperative manner by STIM1, with maximal channel activation requiring binding of 8 STIM1 molecules per channel 15,22,23. We reasoned that if modification of ion selectivity is coupled to the stoichiometry of STIM1 binding, then partial activation of WT Orai1 by a sub-saturating concentration of STIM1 may lead to incomplete normalization of ion selectivity, revealing an intermediate activation state. To test this hypothesis, we used constructs in which WT Orai1 was tethered to either one or two functional STIM1 (S) domains (resulting in four or eight S domains per channel, respectively) as recently described 23. We found that WT Orai1 channels tethered to one S domain per subunit produced currents that were smaller and displayed diminished CDI compared to Orai1-SS currents (Supplementary Fig. 9a), as expected from the known requirement of STIM1 for CRAC channel activation and inactivation 15,22,23. Importantly, reversal potential measurements and ion substitution experiments indicated that unlike Orai1-SS channels, Orai1-S channels exhibited diminished Ca2+ and enhanced Cs+ selectivity (Fig. 4a,b). Similar effects were seen when WT Orai1 was expressed with limiting concentrations of full-length STIM1 (Supplementary Figure 9b). These results support the hypothesis that the V102 mutations stabilize an intermediate channel activation state. To gauge the dose-dependence of ion selectivity modulation by STIM1, we examined reversal potentials of V102C and WT channels tagged to zero, one or two S domains (Fig. 4c,d). Despite the different starting functional states of WT (closed) and V102C (open) channels, STIM1 caused similar, dose-dependent alterations in ion selectivity in both cases, while concomitantly enhancing activation of WT channels (Fig. 4d). Thus, Orai1 channel activation and changes in ion selectivity likely result from the same underlying energetic changes driven by STIM1 binding.

Figure 4. STIM1 dose-dependently modulates the ion selectivity of WT Orai1 channels.

a, The addition of S domains to WT Orai1 produces a rightward shift in the Vrev of ICRAC. I-V relationships of WT Orai1 channels tagged to either one or two S domains in the 20 mM Ca2+ and DVF Ringer's solutions are shown. The bar graphs summarize the Vrev (mean±SEM) in each solution. The top and bottom traces for each condition are from the same cell. b, Effects of substituting extracellular Na+ with an impermeant ion, NMDG+. Removal of Na+ diminishes the inward current in Orai1-S channels, but not Orai1-SS channels. c, I-V relationships and reversal potentials (mean±SEM) of V102C, V102C-S and V102C-SS channels. Increasing the number of S domains to the V102C monomer causes a progressive rightward shift in Vrev of ICRAC. d, A plot of V102C Orai1 Vrev (in the 20 mM Ca2+ Ringer's solution) against current density of WT Orai1 channels tagged to zero, one, or two S domains.

Collectively, our results show that mutations at V102 cause constitutive activation of Orai1 channels through a mechanism likely involving destabilization of the channel gate at V102. This disposition of the STIM1 activation gate, in the extracellular region of the pore close to the selectivity filter (E106), is strikingly different from the familiar structural designs in K+ channels, and voltage-gated Ca2+ (Cav) channels, which are constructed with the gate located at the cytoplasmic end of the pore 24. We exploited the constitutive channel activity resulting from mutations in the putative gate to identify an unusual ion channel gating mode in which STIM1 regulates ion selectivity and the pore architecture of CRAC channels. Activation by STIM1 bestows several key distinctive characteristics classically associated with CRAC channels including high Ca2+ selectivity, low Cs+ permeability, and a narrow pore to otherwise non-selective Orai1 channels. Although the underlying mechanism remains to be established, the close proximity of the putative STIM1 activation gate (V102) to the selectivity filter (E106) likely contributes to the tight coupling of permeation and gating during channel activation. The altered ion selectivity of Orai1 channels when STIM1 is limiting is reminiscent of the ion selectivity of Orai1 and Orai3 channels directly activated by the compound, 2-APB, which exhibit lower Ca2+ selectivity and higher Cs+ selectivity than STIM1-activated Orai channels 25-28. These findings indicate that the exquisite Ca2+ selectivity of CRAC channels is not an intrinsic and immutable property of Orai1 but is rather uniquely manifested only in response to STIM1 gating. Given emerging evidence indicating that Orai1 can be activated in a STIM1-independent manner by other cellular activators 29, these results suggest that activation of highly Ca2+ selective or non-selective Orai1 currents may be a general mechanism for cells to tune Ca2+ and Na+ entry through Orai1 channels depending on the nature of the upstream activation signal.

METHODS SUMMARY

ICRAC was recorded in the standard whole-cell patch clamp configuration in HEK293 cells overexpressing the indicated Orai1 constructs in a bicistronic expression vector that also expressed GFP. The membrane potential was stepped from +30 mV (holding) to -100 mV (100 ms) followed by a ramp from -100 to +100 mV (100 ms) applied every second in a 20 mM Ca2+-containing Ringer's solution. MTS reagents or Cd2+ were added to the extracellular Ringer's or divalent-free solution at the indicated concentrations. Second order rate constants of MTSEA blockade were determined at a constant holding potential of -80 mV as previously described 6. Additional details are provided in the Methods.

METHODS

Cells

HEK293 cells were maintained in suspension in a medium containing CD293 supplemented with 4 mM GlutaMAX (Invitrogen) at 37°C, 5% CO2. For imaging and electrophysiology, cells were plated and adhered to poly-L-lysine coated coverslips at the time of passage, and grown in a medium containing 44% DMEM (Mediatech), 44% Ham's F12 (Mediatech), 10% fetal calf serum (HyClone), 2 mM glutamine, 50 U/ml penicillin and 50 μg/ml streptomycin.

Plasmids and transfections

Cys mutations employed for electrophysiology were engineered into the previously described C-terminal myc-tagged Orai1 construct (MO7O Orai1) in the bicistronic expression vector pMSCV-CITE-eGFP-PGK-Puro 11. The basic “building blocks” for generating the tandem dimers (monomeric Orai1 (MO7O) and the Bluescript SK+ vector with Orai1 attached to a linker) were kind gifts of Dr. Trevor Shuttleworth (U. of Rochester)3. The orientation and number of subunits in the final constructs were confirmed by restriction enzyme analysis and Western blotting. The eGFP-Orai1-S and eGFP-Orai1-SS constructs were kind gifts of Dr. Tau Xu (Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China). The Orai1-CFP, STIM1-YFP, and CFP-Orai3 plasmids have been previously described 21,28. Site-directed mutagenesis to generate Orai1 mutations was performed using the QuikChange™ Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene) according to manufacturer's instructions and confirmed by DNA sequencing. For electrophysiology, the indicated Orai1 constructs were transfected into HEK293 cells either alone or together with a construct expressing unlabeled STIM1 (pCMV6-XL5, Origene Technologies). Cells were transfected with the indicated STIM1 and/or Orai1 cDNA (ratio of 1:10 by mass for electrophysiology) using TransPass D2 (NEB Labs) and studied 24 hours later. Cells transfected with siSTIM1 (Ambion) were studied 72 h following transfection.

Electrophysiology

Currents were recorded in the standard whole-cell configuration at room temperature on an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Molecular Devices) interfaced to an ITC-18 input/output board (Instrutech). Routines developed by R. Lewis (Stanford) on the Igor Pro software (Wavemetrics) and modified by M. Prakriya were employed for stimulation, data acquisition and analysis. Data are corrected for the liquid junction potential of the pipette solution relative to Ringer's in the bath (-10 mV). The holding potential was +30 mV. The standard voltage stimulus consisted of a 100-ms step to –100 mV followed by a 100-ms ramp from –100 to +100 mV applied at 1 s intervals. In most examples, the peak currents during the -100 mV pulse were measured for analysis. For examining Ca2+-dependent fast inactivation, the voltage protocol consisted of a 300-ms step to -100 mV applied at 2 s intervals. Unless otherwise indicated, ICRAC was activated by passive depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores by internal dialysis of 8 mM BAPTA through the pipette solution. To obviate complications arising from the changing membrane potential in standard step-ramp voltage protocol, rate constants of blockade by MTS reagents were determined at a constant potential of -80 mV by acquiring 200 ms sweeps of current at 4 Hz. All currents were acquired at 5 kHz and low pass filtered with a 1 kHz Bessel filter built into the amplifier. All data were corrected for liquid junction potential of the pipette solution and for leak currents collected in 50-150 μM LaCl3.

MTS reagent protocol

The protocol for analysis of state-dependent modification of Orai1-bearing Cys mutants is described in Fig. 1c. For the D110C mutant, this protocol was slightly modified to adjust for the formation of spontaneous disulfide bonds in this mutant 6. The protocol included an additional application of the reducing agent BMS (90-120 s) prior to any MTSEA (or Cd2+) application to remove preexisting disulfide bonds, as described previously 6.

Solutions

The standard extracellular Ringer's solution contained (in mM): 130 NaCl, 4.5 KCl, 20 CaCl2, 10 TEA-Cl, 10 D-glucose, and 5 Na-HEPES (pH 7.4). The Divalent free (DVF) Ringer's solution contained: 150 NaCl, 10 HEDTA, 1 EDTA, 10 TEA-Cl, and 5 Hepes (pH 7.4). The 110 mM Ca2+ solution contained 110 CaCl2, 10 D-Glucose, and 5 Hepes (pH 7.4). The standard internal (pipette) solution contained 135 Cs aspartate, 8 MgCl2, 8 BAPTA, and 10 Cs-HEPES (pH 7.2). In experiments examining CDI, BAPTA was replaced with EGTA to accentuate CDI. In these experiments, the internal solution contained (in mM) 125 Cs aspartate, 10 EGTA, 3 MgCl2, 8 NaCl, and 10 Cs-HEPES(pH 7.2). Stock solutions of MTS reagents (Toronto Research Chemicals) were prepared as previously described 6.

Data analysis

Reversal potentials were measured from the average of several leak-subtracted sweeps (4-6) in each cell. Measurements were taken in 6-15 cells per mutant per condition. In cases where the I-V curve asymptotically approached the X-axis with no clear reversal (e.g. in some WT Orai1 expressing cells), the reversal potential was assigned as +80 mV. MTSEA reaction rate constant was estimated from single exponential fits to the current decline following MTSEA application. The apparent second order modification rate constant kon was calculated from the relationship:

where [MTS] is the concentration of the MTS reagent.

Relative permeabilities were calculated from changes in the reversal potential using the Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz (GHK) voltage equation:

where R, T, and F have their usual meanings, and Px and PNa are the permeabilities of the test ion and Na+, respectively, [X] and [Na] are the ionic concentrations, and ΔErev is the shift in reversal potential when the test cation is exchanged for Na+. To estimate the minimal width of Orai1 channels, the relative permeabilities for a series of organic monovalent cations of increasing size were examined as described before 10. The cations used were: ammonium (3.2 Å), methylammonium (3.78 Å), dimethylammonium (4.6 Å), and trimethylammonium (5.34 Å). These experiments were carried out in buffered Ca2+-free solutions to avoid the potent blocking effects of Ca2+ ions on monovalent ICRAC. The data were fit to the hydrodynamic relationship 10:

where dion is the diameter of the tested ion and dpore the apparent width of the pore.

All data were corrected for leak currents collected in 20 mM Ca2+ + 50-150 μM La3+. All curve fitting was done by least-squares methods using built-in functions in Igor Pro 5.0.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Chris Lingle, Rich Lewis, Kenton Swartz, Jon Sack, Zhe Lu, Adrian Gross, Leida Tirado-Lee and Tara Hornell for helpful discussions and valuable comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by NIH grant NS057499 to M. Prakriya. A.S. was supported by an American Heart Association predoctoral fellowship.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS.

B.A.M. generated, expressed, and functionally characterized the Orai mutants by patch-clamp electrophysiology with help from M.Y. A.S. performed the Ca2+ imaging, FRET imaging, TIRF microscopy, and Western blot analysis of Orai1 mutants. B.A.M, A.S., and M.P. contributed to the writing and editing of the paper.

References

- 1.Olcese R. And yet it moves: conformational States of the Ca2+ channel pore. J. Gen. Physiol. 2007;129:457–459. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200709814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hogan PG, Lewis RS, Rao A. Molecular basis of calcium signaling in lymphocytes: STIM and ORAI. Annu Rev Immunol. 2010;28:491–533. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mignen O, Thompson JL, Shuttleworth TJ. Orai1 subunit stoichiometry of the mammalian CRAC channel pore. J Physiol. 2008;586:419–425. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.147249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Penna A, et al. The CRAC channel consists of a tetramer formed by Stim-induced dimerization of Orai dimers. Nature. 2008;456:116–120. doi: 10.1038/nature07338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Madl J, et al. Resting-state Orai1 diffuses as homotetramer in the plasma membrane of live mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:41135–41142. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.177881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McNally BA, Yamashita M, Engh A, Prakriya M. Structural determinants of ion permeation in CRAC channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:22516–22521. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909574106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou Y, Ramachandran S, Oh-Hora M, Rao A, Hogan PG. Pore architecture of the ORAI1 store-operated calcium channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:4896–4901. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001169107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karlin A, Akabas MH. Substituted-cysteine accessibility method. Methods Enzymol. 1998;293:123–145. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(98)93011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prakriya M, Lewis RS. Regulation of CRAC channel activity by recruitment of silent channels to a high open-probability gating mode. J. Gen. Physiol. 2006;128:373–386. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200609588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamashita M, Navarro-Borelly L, McNally BA, Prakriya M. Orai1 mutations alter ion permeation and Ca2+-dependent inactivation of CRAC channels: evidence for coupling of permeation and gating. J. Gen. Physiol. 2007;130:525–540. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200709872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prakriya M, et al. Orai1 is an essential pore subunit of the CRAC channel. Nature. 2006;443:230–233. doi: 10.1038/nature05122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yeromin AV, et al. Molecular identification of the CRAC channel by altered ion selectivity in a mutant of Orai. Nature. 2006;443:226–229. doi: 10.1038/nature05108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vig M, et al. CRACM1 multimers form the ion-selective pore of the CRAC channel. Curr. Biol. 2006;16:2073–2079. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.08.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mullins FM, Park CY, Dolmetsch RE, Lewis RS. STIM1 and calmodulin interact with Orai1 to induce Ca2+-dependent inactivation of CRAC channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:15495–15500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906781106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scrimgeour N, Litjens T, Ma L, Barritt GJ, Rychkov GY. Properties of Orai1 mediated store-operated current depend on the expression levels of STIM1 and Orai1 proteins. J Physiol. 2009 doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.170662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Derler I, et al. A Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ (CRAC) modulatory domain (CMD) within STIM1 mediates fast Ca2+ -dependent inactivation of ORAI1 channels. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:24933–24938. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C109.024083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feske S, et al. A mutation in Orai1 causes immune deficiency by abrogating CRAC channel function. Nature. 2006;441:179–185. doi: 10.1038/nature04702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doyle DA. Structural changes during ion channel gating. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:298–302. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miyazawa A, Fujiyoshi Y, Unwin N. Structure and gating mechanism of the acetylcholine receptor pore. Nature. 2003;423:949–955. doi: 10.1038/nature01748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang G, Spencer RH, Lee AT, Barclay MT, Rees DC. Structure of the MscL homolog from Mycobacterium tuberculosis: a gated mechanosensitive ion channel. Science. 1998;282:2220–2226. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5397.2220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Navarro-Borelly L, et al. STIM1-Orai1 interactions and Orai1 conformational changes revealed by live-cell FRET microscopy. J Physiol. 2008;586:5383–5401. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.162503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoover PJ, Lewis RS. Stoichiometric requirements for trapping and gating of Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ (CRAC) channels by stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:13299–13304. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1101664108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li Z, et al. Graded activation of CRAC channel by binding of different numbers of STIM1 to Orai1 subunits. Cell Res. 2011;21:305–315. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yellen G. The voltage-gated potassium channels and their relatives. Nature. 2002;419:35–42. doi: 10.1038/nature00978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peinelt C, Lis A, Beck A, Fleig A, Penner R. 2-Aminoethoxydiphenyl borate directly facilitates and indirectly inhibits STIM1-dependent gating of CRAC channels. J Physiol. 2008;586:3061–3073. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.151365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang SL, et al. Store-dependent and -independent modes regulating Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ channel activity of human Orai1 and Orai3. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:17662–17671. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801536200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schindl R, et al. 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate alters selectivity of Orai3 channels by increasing their pore size. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:20261–20267. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803101200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamashita M, Somasundaram A, Prakriya M. Competitive modulation of CRAC channel gating by STIM1 and 2-aminoethyldiphenyl borate (2-APB). J Biol Chem. 2011;286:9429–9442. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.189035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feng M, et al. Store-independent activation of Orai1 by SPCA2 in mammary tumors. Cell. 2010;143:84–98. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.08.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Radzicka A, Pedersen L, Wolfenden R. Influences of solvent water on protein folding: free energies of solvation of cis and trans peptides are nearly identical. Biochemistry. 1988;27:4538–4541. doi: 10.1021/bi00412a047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.