Abstract

Objective

Follistatin-like protein 1 (FSTL-1) is a secreted glycoprotein that exacerbates murine arthritis and is overexpressed in human arthritis. The aim of this study was to determine the mechanism by which FSTL-1 promotes arthritis.

Methods

Collagen-induced arthritis (CIA) was induced in mice hypomorphic for FSTL-1, created with a gene trap-targeted mutant embryonic stem cell line. Arthritis was assessed by measuring paw swelling and using a qualitative arthritic index. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells (MSC) from hypomorphic mice, as well as mouse stromal ST2 cells transduced with short hairpin RNA to suppress FSTL-1 expression, were stimulated with interleukin-1β (IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and IL-17. The monocyte cell line U937, which does not express FSTL-1, was transfected with a plasmid encoding FSTL-1 and stimulated with PMA and LPS. Cell supernatants were assayed for IL-6, IL-8, monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1), and FSTL-1 by ELISA.

Results

FSTL-1 hypomorphic mice had reduced FSTL-1 compared to littermate controls. Following induction of arthritis, a significant correlation was observed between serum FSTL-1 levels and both paw swelling and the arthritic index. A similar correlation was observed between the amount of FSTL-1 produced by MSC, stromal ST2 cells, and monocytes and the secretion of IL-6, IL-8, and MCP-1.

Conclusion

These findings demonstrate that FSTL-1 upregulates proinflammatory mediators important in the pathology of arthritis and that serum levels of FSTL-1 correlate with severity of arthritis. The latter supports the possibility that FSTL-1 might be a target for treatment of certain forms of arthritis.

Follistatin-like protein-1 (FSTL-1), a glycoprotein originally cloned from a mouse osteoblastic cell line as a transforming growth factor β (TGFβ)-inducible gene (1). FSTL-1 is encoded on chromosome 3 in humans and chromosome 16 in mice. The human and mouse FSTL-1 proteins share 92% amino acid homology. Based on sequence homology, FSTL-1 belongs to a family of secreted proteins rich in cysteines (SPARC/BM-40/osteonectin) sharing a characteristic structural module (the follistatin-like domain) and a pair of EF hands (2). However, the EF hand calcium binding domains of FSTL-1 are non-functional (2) and, in contrast to follistatin, FSTL-1 does not bind activin (3) suggesting that FSTL-1 exhibits unique and distinctive properties.

The function of FSTL-1 is poorly understood. Various, seemingly contradictory, effects have been reported on cell growth and survival. FSTL-1 has been reported to inhibit apoptosis in cardiac myocytes (4), to promote endothelial cell function and blood vessel growth through the activating phosphorylation of Akt and eNOS (5), and to enhance metastatic potential in prostate tumors (6). In contrast, FSTL-1 had a tumor suppressor effect in ovarian and endometrial tumors (7) inhibited invasion in rat fibroblasts transformed by FBR-v-fos (8), and inhibited vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration (9).

In the past decade, a number of reports have been published suggesting a role for FSTL-1 in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis (RA). In 1998, Tanaka et al. cloned FSTL-1 from RA synovial tissue and found FSTL-1 autoantibodies in the serum and synovial fluid of RA patients and suggested that it may be an autoantigen (10). Ameliorative effects of human FSTL-1 on joint inflammation in a mouse model of antibody-induced arthritis have also been reported (3).

Our own studies have demonstrated that FSTL-1 expression was increased in RA synovial tissue (11) and in the joints of mice with collagen-induced arthritis (CIA) (12). Over-expression of FSTL-1 exacerbated CIA, while its neutralization with specific antibody ameliorated CIA (11, 13). More recently, we have shown that serum levels of FSTL-1 correlate with active disease in children with a systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) (14). In vitro, over-expression of FSTL-1 increased interferon-γ (IFNγ) secretion from T cells and increased IL-1β, TNF-α and IL-6 secretion from macrophages and fibroblasts (13).

FSTL-1 is produced by endotheliocytes (5), myocytes (5) and various cells of the mesenchymal lineage, including osteocytes, chondrocytes, adipocytes, and fibroblasts (14). In contrast to other proinflammatory mediators, it is not produced by cells of the hematopoetic lineage, such as monocytes and lymphocytes (14). Its expression can be induced by innate immune signals, including Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) agonists and the arthritogenic cytokines, IL-1β, TNF-α and IL-6 (11, 14).

Taken together, these data imply that FSTL-1 plays an important role in the complex network of inflammatory mediators present in the rheumatoid synovium. The current study was designed to further explore the mechanism by which FSTL-1 exerts its proinflammatory effect.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells, transfection and lentivirus transduction

The human monocytic cell line, U937, was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and cultured in RPMI. Mouse stromal ST2 cells (15) were cultured in DMEM. Mouse mesenchymal stromal cells (MSC) were isolated by flushing the femurs and tibias from 8–12-week-old DBA/1 mice and cultured as previously described (16). All cultures were supplemented with heat-inactivated 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS).

U937 were transfected with the plasmid pRcCMV-hFSTL-1 (encoding human FSTL-1 under control of the CMV promoter and a neomycin-resistance gene) or with the control plasmid pRcCMV (encoding the CMV promoter and the neomycin-resistance gene without a transgene) using the Amaxa Nucleofector System (Lonza) according to the manufacturers protocol. Cells were maintained in G418 selection media for a period of 3–4 weeks and clones were isolated.

ST2 cells were transduced with a lentivirus encoding mouse FSTL-1 small hairpin RNA (shRNA) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or a control lentivirus carrying scrambled shRNA according to the manufacturers protocol. ST2 cells expressing low levels of FSTL-1 were selected following cloning by serial dilution.

To induce cytokine production, U937 cells were activated with phorbol myristate acetate (PMA, 10 ng/ml, Sigma) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS, 100 ng/ml, Sigma). Stromal cells were stimulated with IL-1β (10 ng/ml, R&D Systems), TNF-α(2 ng/ml, Fitzgerald) and/or IL-17 (8 ng/ml, R&D Systems).

ELISA

CCL2/MCP-1, IL-6, TNF-α and CXCL8/IL-8 were assayed using commercial reagents (BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Mouse and human FSTL-1 were assayed by coating Nunc Immunomodule MaxiSorp ELISA plates (Nalgene) with 5 μg/ml rat anti-mouse FSTL-1 (MAB1738; R&D Systems) or goat anti-human FSTL-1 (AF1694; R&D Systems) overnight at 4°C. Plates were washed with PBS/0.05% Tween 20 and blocked with 1% BSA/5% sucrose/0.05% Tween 20 for 1 hour. Cell culture supernatants or mouse sera were added at room temperature for 1 hour. After washing, 5 μg/ml biotin-labeled goat anti-mouse FSTL-1 (AF1738; R&D Systems) or rat anti-human FSTL-1 (MAB1694; R&D Systems) was added for 1 hour. Plates were washed and incubated with streptavidin–horseradish peroxidase (Invitrogen) and developed with TMB peroxidase substrate (BD Biosciences). The absorbance of the plates was read at 450 nm on a microplate reader.

Mice

DBA/1 mice, 9–10 weeks of age, were purchased from Taconic. Mice hypomorphic for FSTL-1 (17) were created with a gene trap-targeted mutant embryonic stem cell line (18) obtained from the German Gene Trap Consortium. FSTL-1 hypomorphs were backcrossed onto the DBA/1 (H-2q) genetic background for 6 generations. To generate litters for CIA experiments, male and female mice heterozygous for the FSTL-1 hypomorphic allele were bred to each other and offspring were screened for genotype (wild-type, homozygous, or heterozygous) by PCR. Primers FSTL-1 Forward (5′-ACT GGC TTA AAT TTC ACC CCT CAG G-3′), FSTL-1 Reverse 1 (5′-GCA TCC GAC TTG TGG TCT CGC TGT T-3′) and FSTL-1 Reverse 2 (5′-GTT TCT GGG GTA GCC TGG CCC CGC C-3′) were used to identify hypomorphic mutants. CIA was induced by intra-dermal immunization of DBA/1 mice with bovine collagen type II (Elastin Products), as previously described (19). Mice were evaluated for arthritis several times weekly by a blinded observer. Paw swelling was measured using calipers. Arthritis was also scored using a macroscopic scoring system ranging from 0 to 4 (0 = no detectable arthritis; 1 = swelling and/or redness of paw or 1 digit; 2 = 2 joints involved; 3 = 3–4 joints involved; and 4 = severe arthritis of entire paw and digits). An arthritic index for each mouse was calculated by adding the score of the 4 individual paws. Mice were housed in the animal resource facility at the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh Rangos Research Center (Pittsburgh, PA). The study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh’s Animal Research and Care Committee.

RESULTS

FSTL-1 expression correlates with severity of arthritis

In order to determine whether FSTL-1 plays a role in regulating the inflammatory response in arthritis, we made use of FSTL-1 hypomorphic mice (17) backcrossed onto the CIA-susceptible DBA/1 (IAq) strain. As shown in Figure 1, FSTL-1 homozygous and heterozygous hypomorphs had a reduction in serum FSTL-1 (26.8±2.2 ng/ml and 28.8±2.5 ng/ml, respectively), compared to wild-type littermate controls (34.3±1.8 ng/ml). The heterogeneity in FSTL-1 levels in the hypomorphs provided an opportunity to compare the effects of different levels of FSTL-1 on susceptibility to arthritis. CIA was induced in wild type, heterozygous and homozygous FSTL-1 hypomorphic littermates. Mice were sacrificed on day 39, when arthritis was at its peak, and sera were collected and assayed for FSTL-1. A significant correlation was observed between increasing serum FSTL-1 levels and an increase in both paw swelling (Figure 2A) and the arthritic index (Figure 2B). The incidence and time course of CIA was not significantly altered in hypomorphic mice compared with wild type controls.

Figure 1.

Serum levels of FSTL-1 in homozygous and heterozygous FSTL-1 hypomorphic mice and in wild-type littermate controls. Each point represents an individual mouse (5 mice per group). WT = wild-type; Het = heterozygous hypomorphic; Hom = homozygous hypomorphic.

Figure 2.

Serum FSTL-1 levels positively correlate with arthritis severity. CIA was induced in wild-type, heterozygous and homozygous FSTL-1 hypomorphic DBA/1 mice. Serum FSTL-1 levels on day 39 were compared to paw swelling (A) and the arthritic index (B). Each point represents an individual paw. The Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) and p-value are shown.

FSTL-1 hypomorphic mice produce less proinflammatory cytokines

To determine the mechanism by which reduced FSTL-1 led to a reduction in arthritis, we investigated the inflammatory phenotype of stromal cells from hypomorphic mice. Stromal cells are an important cell population in RA because of their ability to produce inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, and their ability to modulate the functional activity of neutrophils, monocytes, T cells and B cells (20, 21). Stromal cells were isolated from the bone marrow of homozygous hypomorphic mice and wild-type controls. A significant reduction in the secretion of FSTL-1 was observed in the stromal cells of hypomorphic mice (Figure 3A). Following stimulation with IL-1β, cells from hypomorphic mice produced significantly less IL-6, compared to controls (Figure 3B). Similarly, cells from hypomorphic mice produced less MCP-1 following stimulation with IL-1β or TNF-α (Figure 3C). IL-17 exhibited a strong synergistic effect with TNF-α on the induction of IL-6 and MCP-1. This experiment was repeated three times with three different mice of each genotype, with similar results.

Figure 3.

MSC from FSTL-1 hypomorphic mice have a defect in IL-6 and MCP-1 production. MSC were isolated from the bone marrow of homozygous hypomorphs and wild-type controls and cultured for 3 days in the presence or absence of IL-1β (10 ng/ml), TNF-α (2 ng/ml), and/or IL-17 (8 ng/ml). Supernatants were collected and assayed for FSTL-1 (A), IL-6 (B), or MCP-1 (C). Each bar represents the mean ± SEM of triplicate wells. * p<0.05 compared to cells from wild-type controls.

FSTL-1 regulates IL-6, MCP-1, and IL-8

While the above findings suggest that FSTL-1 directly upregulates expression of IL-6 and MCP-1, it was possible that the FSTL-1 hypomorphs had an additional unidentified defect responsible for the observed phenotype. In order to address this possibility, we performed in vitro studies in cell lines in which FSTL-1 expression was specifically targeted. First, the mouse ST2 stromal cell line was transduced with lentivirus encoding mouse FSTL-1 shRNA or a scrambled control shRNA. FSTL-1 shRNA significantly reduced secretion of FSTL-1 from ST2 cells (Figure 4A). Downregulation of FSTL-1 in ST2 cells resulted in a significant reduction in the secretion of IL-6 (Figure 4B) and MCP-1 (Figure 4C) in response to stimulation with IL-17 plus TNF-α. IL-6 secretion was reduced by nearly 75% and MCP-1 secretion by 50%. Inhibition of protein production was associated with a 7.9-fold decrease in IL-6 mRNA level and a 2.3-fold decrease in MCP-1 mRNA level in ST2 cells transduced with FSTL-1 shRNA (data not shown). Addition of soluble FSTL-1 did not increase IL-6 or MCP-1 secretion in ST2-FSTL-1 shRNA cells (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Targeted inhibition of endogenous FSTL-1 expression in ST2 stromal cells leads to suppression of IL-6 and MCP-1 secretion. FSTL-1 gene transcription was targeted by transducing cells with lentivirus encoding FSTL-1 shRNA. Control cells were transduced with lentivirus encoding a scrambled shRNA. Cells were cultured for 2 days in the presence or absence of TNF-α (2 ng/ml) and IL-17 (8 ng/ml). Supernatants were assayed for FSTL-1 (A), IL-6 (B), or MCP-1 (C). Each bar represents the mean ± SEM of triplicate wells. * p<0.05 compared to control cells.

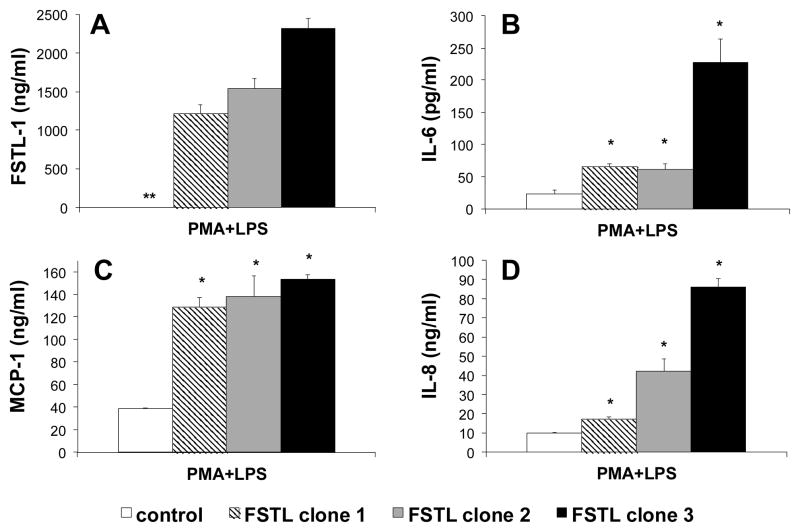

We next transfected the FSTL-1 gene into the monocyte cell line U937, which does not normally express FSTL-1. Three clones expressing high amounts of FSTL-1 were isolated. Low levels of constitutive secretion of IL-8 (<100 pg/ml) and MCP-1 (<1 ng/ml) were measurable in unstimulated clones and control cells, and IL-6 secretion was at the lower limits of detection (data not shown). However, addition of PMA and LPS to induce differentiation towards macrophages and activation of the TLR4 signaling pathway led to a substantial induction of IL-6 (Figure 5B), MCP-1 (Figure 5C) and IL-8 (Figure 5D) by U937 control cells. A significant increase in secretion of all of these cytokines was observed from U937 clones transfected with FSTL-1. A significant positive correlation was observed between the amount of FSTL-1 produced by each clone (Figure 5A) and the amount of IL-6, MCP-1, and IL-8 secreted (regression correlation coefficient of Pearson: FSTL-1 vs. IL-6 r=0.925, p<0.001; FSTL-1 vs. MCP-1 r=0.708, p<0.05; FSTL-1 vs. IL-8 r=0.975, p<0.001).

Figure 5.

Overexpression of FSTL-1 in monocytes leads to increased inflammatory cytokine secretion. The human U937 cell line was transfected with plasmid encoding FSTL-1 or a control plasmid. Clones expressing FSTL-1, as well as control cells, were stimulated with 10 ng/ml PMA and 100 ng/ml LPS for 3 days. Supernatants were assayed for FSTL-1 (A), IL-6 (B), MCP-1 (C) and IL-8 (D). Each bar represents the mean ± SEM of triplicate wells. * p<0.05 compared to control cells. ** FSTL-1 was not detectable in the supernatant of U937 control cells.

DISCUSSION

The current study demonstrates a significant positive correlation between serum FSTL-1 levels and arthritis severity in mice, lending further support to a likely role for FSTL-1 in arthritis. This conclusion is supported by our previous studies demonstrating that overexpression of FSTL-1 in mice exacerbates CIA (11) while its neutralization suppresses CIA (13).

The results described here provide additional insight into the mechanism of the arthritogenic effects of FSTL-1. FSTL-1 overexpression increases IL-6, IL-8 and MCP-1 synthesis by activated macrophages and stromal cells. We observed a direct correlation between FSTL-1 production and secretion of these inflammatory mediators, suggesting that FSTL-1 plays a role in the regulation of their expression. How FSTL-1 acts to do so is currently unclear, however the broad proinflammatory effects of FSTL-1 that we have observed suggest that it may act as an adjuvant to amplify the release of proinflammatory mediators. In addition, this hypothesis is supported by our previous data showing the ability of FSTL-1 to promote T cell response and to induce IFNγ (11).

The centrality of IL-6, IL-8 and MCP-1 to mouse and human arthritis is well known and our data therefore suggest a direct role for FSTL-1 in arthritis. IL-6 is a pleiotropic cytokine with a pivotal role in the pathophysiology of rheumatoid arthritis (22). The neutrophil chemoattractant IL-8, and monocyte chemotactic protein-1, are the most potent chemokines of C-X-C and C-C families, respectively. These chemokines drive the recruitment, activation and effector function of neutrophils, monocytes/macrophages, T cells, NK cells, and are secreted by multiple cellular sources in the site of synovial inflammation (23). IL-8 and MCP-1 play critical roles at all stages of autoimmune joint diseases from an acute to a chronic inflammatory phase (23). IL-8 and MCP-1 are known to play major roles in regulating the trafficking of myelomonocytoid cells and T lymphocytes into inflammatory sites (24). Enhanced production of IL-8 and MCP-1 in established RA correlated with a higher disease activity (23). In addition, we previously reported a role of FSTL-1 for CXCL10/IP-10 (11), a central mediator of bone erosion in CIA (25). These previous results, together with the current data, suggest that FSTL-1 enhances the accumulation of mononuclear cells and neutrophils in the synovium via production of chemokines. Our previous work demonstrating overexpression of FSTL-1 in RA synovium (14) provides clinical relevance to these findings.

The role of mesenchymal stromal cells in activation of inflammatory cells and regulation of their migration into the synovium is still not fully understood. However, mesenchymal stromal cells can differentiate into cells of joint matrix, including fibroblasts, chondrocytes, osteoblasts and adipocytes (21). We have previously demonstrated that all cells of the mesenchymal lineage are able to produce FSTL-1 (14). IL-6, IL-8, and MCP-1 are induced by many factors including TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-17 and others (26–28). Herein, we demonstrated that downregulation of FSTL-1 resulted in substantial suppression of IL-6, IL-8, and MCP-1 production in cytokine-activated mouse bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells and stromal ST2 cells. In the context of arthritis this finding suggests that FSTL-1 is an important regulatory cytokine amplifying the release of proinflammatory mediators by the cells of arthritic joints.

It has previously been reported that IL-17 synergizes with several proinflammatory mediators (e.g. TNF-α, IFNγ, and IL-1β) to induce the secretion of IL-6 by rheumatoid synoviocytes (27, 29) and chemokine release from epithelial cells (28). It is noteworthy that in our experiments FSTL-1 synergized with IL-17 and TNF-α to induce IL-6 in stromal cells. IL-6 has a crucial role in regulating the Treg/Th17 balance (30). Overexpression of IL-6 leads to arthritis, in which Th17 cells are considered to be the initiators of inflammation (30). Of particular interest to the current study, TGFβ has been reported to synergize with IL-6 to promote the development of Th17 (31–33). FSTL-1 is induced by TGFβ (1, 11), suggesting that FSTL-1 may be involved in the IL-6-Th17 axis. We propose that dysregulation/overexpression of FSTL-1 may cause local Th17 induction leading to aggravation of synovial inflammation. Studies to address this possibility are currently underway. Also, FSTL-1-induced release of MCP-1 and IL-8 in the joint space might play an important detrimental role in the pathogenesis of RA by enhancing the infiltration of neutrophils and mononuclear cells. We have previously shown that overexpression of FSTL-1 in mouse paws by gene transfer results in severe inflammation characterized by infiltration of neutrophils and mononuclear cells and cartilage destruction (13). The observation that FSTL-1 influences IL-8 and MCP-1 secretion provides a possible mechanism for recruitment of these cells into the joint.

While the serum FSTL-1 levels in homozygous hypomorphic mice were only modestly reduced, bone marrow-derived MSC from these mice showed a more marked reduction in FSTL-1 secretion. Thus, serum FSTL-1 level may not be a good predictor of disease, at least in the CIA model. We have observed a stronger correlation between serum FSTL-1 and disease in the systemic sub-type of JIA (14). In contrast to other forms of JIA, systemic JIA is characterized by increased IL-1β and IL-6 and patients with systemic JIA often respond to treatment with IL-1β and IL-6 antagonists (34, 35). The current study, demonstrating an effect of FSTL-1 on IL-6, coupled with our earlier observation that FSTL-1 also upregulates IL-1β (13), provide a basis for the possible use of FSTL-1 as a biomarker for diseases in which these cytokines play a central role. We are currently investigating this possibility.

In conclusion, our data demonstrate that FSTL-1 has potent proinflammatory properties that can exacerbate arthritis. Furthermore, the correlation of FSTL-1 serum levels with CIA severity suggests that it might be a potential therapeutic target in arthritis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIH (grants RO1-AI-073556, RO1-AR-056959 to Dr. Hirsch) and the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC.

Footnotes

The University of Pittsburgh has filed a patent application for the use of follistatin-like protein 1 (FSTL-1) as a disease target.

References

- 1.Shibanuma M, Mashimo J, Mita A, Kuroki T, Nose K. Cloning from a mouse osteoblastic cell line of a set of transforming-growth-factor-beta 1-regulated genes, one of which seems to encode a follistatin-related polypeptide. Eur J Biochem. 1993;217(1):13–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb18212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hambrock HO, Kaufmann B, Muller S, Hanisch FG, Nose K, Paulsson M, et al. Structural characterization of TSC-36/Flik: analysis of two charge isoforms. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(12):11727–35. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309318200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kawabata D, Tanaka M, Fujii T, Umehara H, Fujita Y, Yoshifuji H, et al. Ameliorative effects of follistatin-related protein/TSC-36/FSTL1 on joint inflammation in a mouse model of arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(2):660–8. doi: 10.1002/art.20023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oshima Y, Ouchi N, Sato K, Izumiya Y, Pimentel DR, Walsh K. Follistatin-like 1 is an Akt-regulated cardioprotective factor that is secreted by the heart. Circulation. 2008;117(24):3099–108. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.767673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ouchi N, Oshima Y, Ohashi K, Higuchi A, Ikegami C, Izumiya Y, et al. Follistatin-like 1, a secreted muscle protein, promotes endothelial cell function and revascularization in ischemic tissue through a nitric-oxide synthase-dependent mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(47):32802–11. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803440200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trojan L, Schaaf A, Steidler A, Haak M, Thalmann G, Knoll T, et al. Identification of metastasis-associated genes in prostate cancer by genetic profiling of human prostate cancer cell lines. Anticancer Res. 2005;25(1A):183–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan QK, Ngan HY, Ip PP, Liu VW, Xue WC, Cheung AN. Tumor suppressor effect of follistatin-like 1 in ovarian and endometrial carcinogenesis: a differential expression and functional analysis. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30(1):114–21. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnston IM, Spence HJ, Winnie JN, McGarry L, Vass JK, Meagher L, et al. Regulation of a multigenic invasion programme by the transcription factor, AP-1: re-expression of a down-regulated gene, TSC-36, inhibits invasion. Oncogene. 2000;19(47):5348–58. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu S, Wang L, Wang W, Lin J, Han J, Sun H, et al. TSC-36/FRP inhibits vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration. Exp Mol Pathol. 2006;80(2):132–40. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tanaka M, Ozaki S, Osakada F, Mori K, Okubo M, Nakao K. Cloning of follistatin-related protein as a novel autoantigen in systemic rheumatic diseases. Int Immunol. 1998;10(9):1305–14. doi: 10.1093/intimm/10.9.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clutter SD, Wilson DC, Marinov AD, Hirsch R. Follistatin-like protein 1 promotes arthritis by up-regulating IFN-gamma. J Immunol. 2009;182(1):234–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.1.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thornton S, Sowders D, Aronow B, Witte DP, Brunner HI, Giannini EH, et al. DNA microarray analysis reveals novel gene expression profiles in collagen-induced arthritis. Clin Immunol. 2002;105(2):155–68. doi: 10.1006/clim.2002.5227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miyamae T, Marinov AD, Sowders D, Wilson DC, Devlin J, Boudreau R, et al. Follistatin-like protein-1 is a novel proinflammatory molecule. J Immunol. 2006;177(7):4758–62. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.7.4758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson DC, Marinov AD, Blair HC, Bushnell DS, Thompson SD, Chaly Y, et al. Follistatin-like protein 1 is a mesenchyme-derived inflammatory protein and may represent a biomarker for systemic-onset juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(8):2510–6. doi: 10.1002/art.27485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shen F, Hu Z, Goswami J, Gaffen SL. Identification of common transcriptional regulatory elements in interleukin-17 target genes. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(34):24138–48. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604597200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peister A, Mellad JA, Larson BL, Hall BM, Gibson LF, Prockop DJ. Adult stem cells from bone marrow (MSCs) isolated from different strains of inbred mice vary in surface epitopes, rates of proliferation, and differentiation potential. Blood. 2004;103(5):1662–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adams DC, Karolak MJ, Larman BW, Liaw L, Nolin JD, Oxburgh L. Follistatin-like 1 regulates renal IL-1beta expression in cisplatin nephrotoxicity. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2010;299(6):F1320–7. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00325.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Friedrich G, Soriano P. Promoter traps in embryonic stem cells: a genetic screen to identify and mutate developmental genes in mice. Genes Dev. 1991;5(9):1513–23. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.9.1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hughes C, Wolos JA, Giannini EH, Hirsch R. Induction of T helper cell hyporesponsiveness in an experimental model of autoimmunity by using nonmitogenic anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody. J Immunol. 1994;153(7):3319–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takeuchi E, Tomita T, Toyosaki-Maeda T, Kaneko M, Takano H, Hashimoto H, et al. Establishment and characterization of nurse cell-like stromal cell lines from synovial tissues of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42(2):221–8. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199902)42:2<221::AID-ANR3>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bouffi C, Djouad F, Mathieu M, Noel D, Jorgensen C. Multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells and rheumatoid arthritis: risk or benefit? Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009;48(10):1185–9. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dayer JM, Choy E. Therapeutic targets in rheumatoid arthritis: the interleukin-6 receptor. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010;49(1):15–24. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koch AE. Chemokines and their receptors in rheumatoid arthritis: future targets? Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(3):710–21. doi: 10.1002/art.20932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baggiolini M, Dewald B, Moser B. Human chemokines: an update. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:675–705. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kwak HB, Ha H, Kim HN, Lee JH, Kim HS, Lee S, et al. Reciprocal cross-talk between RANKL and interferon-gamma-inducible protein 10 is responsible for bone-erosive experimental arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(5):1332–42. doi: 10.1002/art.23372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yao Z, Fanslow WC, Seldin MF, Rousseau AM, Painter SL, Comeau MR, et al. Herpesvirus Saimiri encodes a new cytokine, IL-17, which binds to a novel cytokine receptor. Immunity. 1995;3(6):811–21. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90070-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fossiez F, Djossou O, Chomarat P, Flores-Romo L, Ait-Yahia S, Maat C, et al. T cell interleukin-17 induces stromal cells to produce proinflammatory and hematopoietic cytokines. J Exp Med. 1996;183(6):2593–603. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.6.2593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Awane M, Andres PG, Li DJ, Reinecker HC. NF-kappa B-inducing kinase is a common mediator of IL-17-, TNF-alpha-, and IL-1 beta-induced chemokine promoter activation in intestinal epithelial cells. J Immunol. 1999;162(9):5337–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chabaud M, Fossiez F, Taupin JL, Miossec P. Enhancing effect of IL-17 on IL-1-induced IL-6 and leukemia inhibitory factor production by rheumatoid arthritis synoviocytes and its regulation by Th2 cytokines. J Immunol. 1998;161(1):409–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kimura A, Kishimoto T. IL-6: regulator of Treg/Th17 balance. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40(7):1830–5. doi: 10.1002/eji.201040391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bettelli E, Carrier Y, Gao W, Korn T, Strom TB, Oukka M, et al. Reciprocal developmental pathways for the generation of pathogenic effector TH17 and regulatory T cells. Nature. 2006;441(7090):235–8. doi: 10.1038/nature04753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mangan PR, Harrington LE, O’Quinn DB, Helms WS, Bullard DC, Elson CO, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta induces development of the T(H)17 lineage. Nature. 2006;441(7090):231–4. doi: 10.1038/nature04754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Veldhoen M, Hocking RJ, Atkins CJ, Locksley RM, Stockinger B. TGFbeta in the context of an inflammatory cytokine milieu supports de novo differentiation of IL-17- producing T cells. Immunity. 2006;24(2):179–89. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nigrovic PA, Mannion M, Prince FH, Zeft A, Rabinovich CE, van Rossum MA, et al. Anakinra as first-line disease-modifying therapy in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis: report of forty-six patients from an international multicenter series. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(2):545–55. doi: 10.1002/art.30128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Benedetti F. Targeting interleukin-6 in pediatric rheumatic diseases. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2009;21(5):533–7. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e32832f1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]