Abstract

Background

Oxytocin (OXT) has been implicated in reproduction and social interactions as well as in the control of digestion and blood pressure. OXT-immunoreactive axons occur in the dorsal vagal complex (DVC; nucleus tractus solitarius, NTS, dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus, DMV, and area postrema, AP), which contains neurons that regulate autonomic homeostasis. The aim of the present work was to provide a systematic investigation of the OXT-immunoreactive innervation of DVC neurons involved in the control of gastrointestinal (GI) function.

Methods

We studied DMV neurons identified by 1) prior injection of retrograde tracers in the stomach, ileum or cervical vagus or 2) induction of c-fos expression by glucoprivation with 2-deoxyglucose. Another subgroup of DMV neurons was identified electrophysiologically by stimulation of the cervical vagus and then juxtacellularly labelled with biotinamide. We used two- or three-color immunoperoxidase labelling for studies at the light microscopic level.

Results

Close appositions from OXT-immunoreactive varicosities were found on the cell bodies, dendrites and axons of DMV neurons that projected to the GI tract and that responded to 2-deoxyglucose as well as juxtacellularly-labelled DMV neurons. Double staining for OXT and choline acetyltransferase revealed that OXT innervation was heavier in the caudal and lateral DMV than in other regions. OXT-immunoreactive varicosities also closely apposed a small subset of tyrosine hydroxylase-immunoreactive NTS and DMV neurons.

Conclusions and inferences

Our results provide the first anatomical evidence for direct OXT-immunoreactive innervation of GI-related neurons in the DVC.

Keywords: Dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus, Nucleus of the solitary tract, Stomach, Tyrosine hydroxylase, Ultrastructure, Immunoreactivity

INTRODUCTION

The dorsal vagal complex (DVC) consists of the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS), dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus (DMV) and area postrema (AP). The DVC contains all of the circuitry required for the activation of vago-vagal reflexes. Regardless of modality, information from thoracic and subdiaphragmatic organs, including the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, is transmitted by vagal afferents to the NTS (reviewed by1–5). Heterogeneous subpopulations of second-order NTS neurons receive synaptic inputs from central vagal afferent terminals as well as inputs from higher centers involved in the regulation of autonomic functions2,4,6–8. Information from these converging inputs is integrated with metabolic and hormonal signals to shape the resulting output, which is conveyed to other caudal brainstem nuclei, such as the DMV, and other CNS sites.

Vagal preganglionic neurons in the DMV are involved in controlling gastrointestinal and endocrine functions4. DMV neurons are organized in mediolateral columns spanning its entire rostrocaudal extent9–11. These columns represent the DMV populations that send efferent axons through the five subdiaphragmatic branches of the vagus. Efferent axons in the anterior and posterior gastric vagal branches originate from somata in the medial portions of the DMV, while neurons in the lateral portions of the DMV send axons to the celiac and accessory celiac branches. Neurons scattered throughout the left DMV provide axons to the hepatic branch. This columnar mediolateral DMV organization is not maintained at the target organs supplied by the various vagal branches12. The gastric branches innervate, amongst other organs, the stomach, duodenum and pancreas. The celiac branches supply the intestine from duodenum to transverse colon. The hepatic branch innervates portions of the stomach, liver, and proximal duodenum.

The neuropeptide oxytocin (OXT) is present in DVC axons that arise from parvocellular neurons in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN)13–16. OXT in the DVC has well-documented physiological roles in gut function17–21. OXT is released following ingestion of a meal22 and activation of OXT receptors on DMV neurons increases their firing rate, possibly via the opening of a sustained sodium conductance sensitive to agents that modulate cAMP23,24. The OXT-mediated activation of brainstem vagal motor neurons profoundly inhibits GI motility and stimulates gastric acid secretion19,20,25. Intracerebroventricular administration of OXT reduces food intake in rats, an effect that can be blocked by OXT antagonists26. The OXT pathway from PVN to DVC may also be functionally important in providing tonic inhibitory drive to the pancreas since injecting OXT or an OXT antagonist into the DVC affects plasma insulin levels27. OXT can also modulate reflex control of the heart at the level of the DVC14.

High densities of OXT binding sites occur medially and rostrally within the DMV. Some of these receptors are likely located on vagal preganglionic neurons since OXT binding in the DMV is abolished by subnodose vagotomy28,29. At the cellular level, OXT excites NTS and DMV neurons24. Recently, we have also shown that OXT selectively increases the release probability of glutamate from vagal afferents onto NTS neurons16.

Central application of OXT has anxiolytic effects, attenuates activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis in response to chronic stress and mediates adaptation to repeated restraint stress in mice30–33. In healthy humans, acute stress inhibits gastric emptying, supporting a pathological role for stress in dyspeptic symptoms; and chronic stress induces symptoms of functional dyspepsia (FD). In dyspepsia patients, stress-related alterations in gastric motility are among the main pathophysiological mechanisms producing dyspeptic symptoms although the relative contribution of stress varies substantially between different patient subgroups. Furthermore, most FD patients associate stressful life events with initiation or exacerbation of symptoms34–37 and appear more susceptible to gastric dysmotility following stress. Anger stress, for example, inhibits gastric motility in FD patients but not in healthy volunteers34.

Physiological evidence shows that OXT acts directly on NTS and DMV neurons that control the stomach; however, little is known about which functional groups of DVC neurons receive OXT-containing innervation. In this study, we aimed to provide the first systematic investigation of the OXT-immunoreactive innervation of DVC neurons involved in the control of gastrointestinal (GI) function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sprague-Dawley rats of both sexes were used. Juxtacellular labeling was carried out under a U.K. Home Office License in accordance with the U.K. Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act, 1986. The Animal Welfare Committees of Flinders University or the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Penn State College of Medicine approved other procedures.

2-deoxyglucose activation

Rats were fasted overnight (water ad libitum) before receiving subcutaneous injections of either saline or 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG, 400 mg/kg). In a subset of rats (n=8), cardiovascular variables were measured before and during 2-DG treatment. Femoral arteries were catheterized under isoflurane anesthesia the day before treatment. Baseline mean arterial pressure (MAP) and heart rate were recorded at 5-minute intervals for 30 minutes before 2-DG/saline. After 2-DG/saline, MAP and heart rate were measured every 10 minutes until perfusion at 2 hours.

Retrograde labeling

To retrogradely label DMV neurons, cholera toxin B subunit (CTB, 1 μl of 0.5% or 2 μl of 0.25%) was injected with glass micropipettes into 3 peripheral sites: the gastric corpus, ileum or cervical vagus nerve. The stomach, or distal ileum, was exposed through a laparotomy and 4–5 CTB injections per rat were placed along the major curvature of the gastric corpus (n=8) or along the anti-mesenteric side of the distal ileum about 1 cm aboral from the ileo-caecal junction (n=5). Vagal fibers of passage are absent in both regions.

The incisions were closed with 5-0 suture (muscle) and staples (skin), rats were administered carpofen 5mg/kg s.c. as needed. Animals were fixed via transcardial perfusion 3–4 days post-surgery (see below).

Juxtacellular labeling

Individual DMV neurons were identified and juxtacellularly labeled using our previously described and established protocols38,39. Briefly, male rats were pentobarbitone-anaesthetized, artificially ventilated, neuromuscularly blocked, fixed on a stereotaxic frame and the exposed cervical vagus was placed on a bipolar silver wire electrode before being covered with paraffin wax or stabilized with dental impression material. DMV neurons were identified by antidromic stimulation and confirmed with collision test. Glass micropipettes filled with 1.5–2.5% Neurobiotin recorded single-unit activity; extracellular signals were filtered and amplified. For labeling, vagal-responsive neurons received positive current pulses through the recording electrode to entrain the cell to fire with the current pulses (20 seconds to 6 minutes). Current amplitude was adjusted continuously to maintain entrainment38. Rats were fixed 1–2 hours after the final fill.

Tissue Processing

2-DG or saline-treated rats and rats with GI injections of CTB were anesthetized and perfused transcardially with heparin, DMEM/F12 culture medium and phosphate-buffered 4% formaldehyde. Brains were post-fixed 3–4 days at room temperature. Following juxtacellular labeling, rats were perfused with heparinized saline before formaldehyde and brains were post-fixed at 4°C. Medullas were cut on a cryostat into 4 series of 30μm transverse sections.

Immunocytochemistry

Immunocytochemistry was done at room temperature on a shaker. Primary antisera (Table 1) were titrated to determine optimal dilutions. Secondary antibodies were biotinylated donkey immunoglobulins (IgGs) for multiple labelling (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove PA) diluted 1:500. ExtrAvidinhorseradish peroxidase (ExtrAvidin-HRP; Sigma) diluted 1:1,500 revealed antibody binding.

Table 1.

Primary Antibodies

| Primary Antibodies Antigen | Immunogen | Manufacturer, Species antibody was raised in, Mono- vs. polyclonal, Catalog & Lot number | Dilution used | Adsorption Controla |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxytocin (OXT) | Oxytocin (H-Cys-Tyr-Ile-Gln-Asn-Cys-Pro-Leu-Gly-NH2) | Peninsula / Bachem, guinea-pig, polyclonal, Catalogue # T-5021, Lot # 0501063, purchased 7/2004 | 1:250,000 or 1:500,000 | 1:250,000b 10 μg/ml OXT |

| Choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) | Human placental choline acetyltransferase | Chemicon (Temecula, CA, USA), goat polyclonal, Catalog # AB144P, Lot #18110644 | 1:5,000 | 1:2,000c 2 μg/ml ChAT |

| Tyrosine Hydroxylase (TH) | Tyrosine hydroxylase from rat pheochromocytoma (denatured with sodium dodecyl sulfate) | Chemicon International , rabbit, polyclonal, Catalogue # AB152, Lot # LV1375881, LV1382810 | 1:40,000 | |

| Cholera toxin B subunit (CTB) | B subunit (choleragenoid) of cholera toxin isolated from Vibrio cholerae type Inaba 569B | List Biological Laboratories (Campbell, CA, USA), goat polyclonal, Catalog # 703; Lot #GAC-01A, purchased 8/1989 | 1:800,000 | 1:100,000d 1 μg/ml CTB |

| Fos | A peptide mapping within an internal region of c-Fos of human origin | Santa Cruz Biotechnology, rabbit polyclonal, Catalog # sc-253, Lot # F131, purchased 11/2001 | 1:5,000 | 1:5,000e 0.1 μg/ml Fos |

Light microscopy (LM)

All LM sections were washed 3 × 10 minutes in Tris-phosphate-buffered saline (TPBS) containing 0.3% Triton X-100 and 0.05% thimerosal and then blocked in 10% normal horse serum (NHS) in TPBS-Triton. Diluents were TPBS-Triton-10% NHS for primary antibodies, TPBS-Triton-1% NHS for secondary antibodies and TPBS-Triton for ExtrAvidin-HRP. Incubations were 3–4 days for primary antisera, overnight for secondary antibodies and 4–6 hours for ExtrAvidin-HRP. After each incubation, sections received 3 × 10 minutes TPBS washes. Immunostained sections were mounted on subbed slides, dehydrated and coverslipped.

Two color immunoperoxidase labeling was used to localize OX T-immunoreactivity (black product) and either choline acetyltransferase (ChAT)-, tyrosine hydroxylase (TH)- or CTB-immunoreactivity (brown product).

After permeabilization and NHS blocking, sections from untreated rats or rats with gut injections of CTB were exposed to guinea-pig anti-OXT antiserum (Table 1), biotinylated anti-guinea-pig IgG and ExtrAvidin-HRP followed by a cobalt- and nickel-intensified diaminobenzidine (DAB) reaction40. After a second NHS block, sections from untreated rats were exposed to goat anti-ChAT (Table 1) or rabbit anti-TH (Table 1) and sections from CTB-injected rats, to goat anti-CTB (Table 1). Secondary antibodies were biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG to localize TH or biotinylated anti-goat IgG to localize ChAT or CTB. After ExtrAvidin-HRP exposure, an imidazole-intensified DAB reaction40 stained immunoreactive neurons brown.

Sections from 2-DG- or saline-treated rats were incubated in anti-OXT plus anti-Fos (Table 1), biotinylated anti-guinea-pig IgG plus biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG and ExtrAvidin-HRP. A cobalt+nickel-DAB reaction simultaneously revealed OXT-and Fos-immunoreactivity. Then, TH- or ChAT-immunoreactivity was visualized with imidazole-DAB.

For demonstrating OXT appositions on juxtacellularly-labeled neurons38,41, all sections from each medulla were treated with 1% H2O2 before permeabilization and NHS blocking. The sections were incubated in 1:250 ExtrAvidin-HRP plus anti-OXT. Juxtacellularly-labeled neurons were visualized with imidazole-DAB. Then sections were incubated in biotinylated anti-guinea-pig IgG and 1:1,500 ExtrAvidin-HRP. A nickel-DAB reaction revealed OXT-immunoreactivity.

Three-color immunoperoxidase labeling was used to localize OXT, ChAT and TH in untreated rats and Fos, OXT, ChAT and TH in 2-DG treated rats. Using the two-color protocol, OXT-immunoreactivity with or without Fos-immunoreactivity was localized with cobalt+nickel-DAB and ChAT-immunoreactivity, with imidazole-DAB. After a third NHS block, the sections were incubated in rabbit anti-TH, biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG and ExtrAvidin-HRP. TH-immunoreactivity was localized with a Vector SG kit with glucose oxidase generating peroxide42.

Image Capture and Analysis

LM images were captured with a SPOT RT color camera and digitally adjusted with Adobe PhotoShop.

Digital images of juxtacellularly labeled neurons were reconstructed in layers using Photoshop. OXT-immunoreactive close appositions were identified on reconstructed neurons using a ×100 oil immersion lens. A close apposition was identified when (1) no space could be discerned between a varicosity and the neuron for terminals lying side-by-side with a filled neurons or when (2) the terminal and the filled neuron were in the same focal plane for varicosities overlying filled neurons. Two criteria identified synapses: pre-synaptic vesicle clustering and post-synaptic densities.

RESULTS

Distribution of OXT axons in the DVC

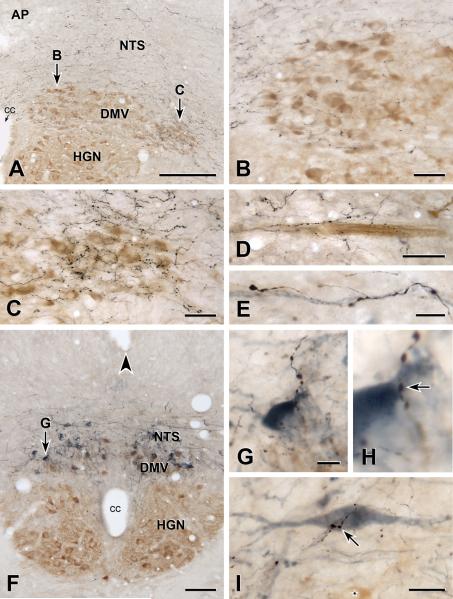

OXT-immunoreactive axons occurred throughout the rostrocaudal extent of the NTS and DMV. In the NTS, the distribution of OXT-positive axons was relatively homogeneously, as we have reported previously for caudal NTS16. In contrast, OXT-immunoreactive axons were heterogeneously distributed in the DMV (Figure 1A–D). In the subpostremal DMV (Figure 1A–C), the density of OXT-positive axons was lower medially (Figure 1B) and higher laterally (Figure 1C). OXT-immunoreactive axons were also dense more caudally in the DMV, and caudal to calamus scriptorius. The density of OXT-positive axons in this region and in the lateral rostral subpostremal DMV was similar. OXT-immunoreactive axons were also occasionally present among the bundles of ChAT-positive DMV axons that traveled from the ventrolateral edge of the DMV to exit points in the ventrolateral medulla (Figure 1D).

FIGURE 1. OXT-immunoreactive innervation of cholinergic and catecholaminergic DVC neurons.

A–D: Two-color immunoperoxidase staining for OXT plus ChAT. E–I: Three-color immunoperoxidase staining for OXT plus ChAT plus TH. A: DVC near the middle of the area postrema (AP). Arrows B and C, locations of Figures 1B and 1C. Bar, 250 μm. B: DMV at arrow B in 1A. OXT-immunoreactive axons (black) are sparse around ChAT-immunoreactive neurons (brown) in the medial DMV at mid-AP level. Bar, 50 μm. C: DMV at arrow C in 1A. OXT-immunoreactive axons (black) are dense around ChAT-immunoreactive neurons (brown) in the lateral DMV at mid-AP level. Bar, 50 μm. D: OXT-immunoreactive axons (black) associated with a bundle of ChAT-positive axons (brown) traveling towards the ventral surface of the medulla. Bar, 50 μm. E: An OXT-immunoreactive axon (black) near a TH-immunoreactive axon (blue-grey) that travels toward the ventral surface. Bar, 10 μm. F: DVC at the level of the obex (arrowhead). Arrow G, location of Figures 1G and 1H. Some DMV neurons are double-labeled for ChAT (brown) and TH (blue-grey). cc, central canal; DMV, dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus, HGN hypoglossal nucleus; NTS, nucleus tractus solitarius. Bar, 100 μm. G & H: The terminal of an OXT-immunoreactive axon (black) closely apposes (arrow in H) the proximal dendrite of a TH-immunoreactive NTS neuron (blue-grey) that lies just dorsal to the DMV. Bar in G, 10 μm. I: An OXT-immunoreactive axon terminal (black) closely apposes (arrow in H) the cell body of a TH-immunoreactive NTS neuron (blue-grey) that lies about 250 micrometers rostral to calamus scriptorius. A ChAT-immunoreactive neuron in the DMV (star, brown) lies ventromedial to the TH neuron. Bar, 20 μm.

As in the NTS16, OXT-immunoreactive axons in the DMV varied in their morphology. Most axons had fine varicosities with thin intervaricose segments, however, occasional axons throughout the rostrocaudal extent of the DVC were thick with large varicosities.

OXT axons appose neurochemically-identified DVC neurons

Sections stained for OXT and ChAT or TH showed OXT-positive terminals apposing both types of neurochemically distinct somata. To determine whether the TH-positive neurons were in the DMV or NTS, we adopted a triple staining approach, localizing OXT with black reaction product, ChAT with brown product and TH with blue-grey product. We also lightly stained for ChAT so that brown ChAT staining and blue-grey TH staining were visible in the same cell. Triple-staining established conclusively that (1) OXT axons closely apposed TH-positive NTS neurons (Figures 1G–1I) and that (2) a subset of the DMV neurons with OXT appositions were both ChAT-positive and TH-positive. OXT-immunoreactive axons also traveled with TH-immunoreactive axons from the DMV to the ventral medullary surface.

OXT axons appose GI-projecting DMV neurons

CTB injection into the corpus labeled many neurons that spanned the entire length of the DMV; these corpus-projecting neurons were distributed bilaterally in the medial DMV. Fewer DMV neurons were labeled after injections of CTB into the ileum. These neurons were distributed bilaterally in the lateral DMV throughout its rostro-caudal extent.

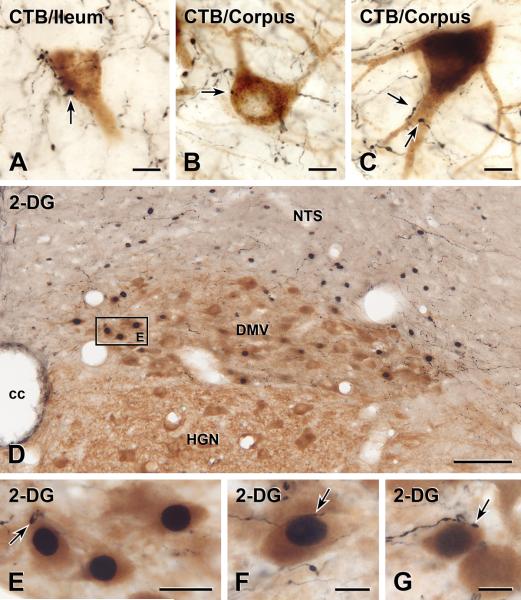

DMV neurons labeled with CTB from the ileum (Figure 2A) or from the corpus (Figures 2B–C) received close appositions from OXT-immunoreactive axons.

FIGURE 2. OXT-immunoreactive innervation of functionally-identified DMV neurons.

A–C: Two-color immunoperoxidase staining for OXT plus CTB. D–G: Two-color immunoperoxidase staining for OXT plus Fos plus ChAT. A: An ileum-projecting DMV neuron receives close appositions from OXT-immunoreactive varicosities, one of which is arrowed. Bar, 10 μm. B: A small OXT-immunoreactive varicosity (black) closely apposes the cell body of a corpus-projecting DMV neuron (brown). Bar, 10 μm. C: OXT-immunoreactive varicosities (black) from two separate axons closely appose the proximal dendrite of a corpus-projecting DMV neuron (brown). Bar, 10 μm. D: DVC at mid-AP level. Square E, DMV neurons in Figure 2E. ChAT-immunoreactive neurons (brown) with Fos-immunoreactive nuclei (black) are concentrated in the medial DMV. Bar, 100 μm. E: DMV neurons outlined by box E in panel 2D. The nuclei of 3 ChAT-positive DMV neurons (brown) show 2-DG-induced Fos. The neuron on the left is closely apposed by a large OXT-immunoreactive varicosity (black, arrow). Bar, 20 μm. F: A small varicosity on a fine OXT-immunoreactive axon (black) closely apposes (arrow) a ChAT-positive DMV neuron (brown) with 2-DG-evoked Fos (black). Bar, 10 μm. G: A large varicosity on a thick OXT-immunoreactive axon (black) close apposes (arrow) a ChAT-positive DMV cell body (brown) showing 2-DG-induced Fos (black). This neuron was located near the obex. Bar, 10 μm.

Oxytocin-positive appositions onto identified corpus-projecting neurons were distributed preferentially in areas caudal to calamus scriptorius, where 81 of 109 (i.e. 74.3%; n=4 rats) DMV neurons received oxytocin-positive appositions. Conversely, in regions rostral to area postrema 31 of 142 (i.e. 21.8%; n=4 rats) DMV neurons received oxytocin-positive appositions.

Since ileum-projecting neurons did not show rostro-caudal differences in the distribution of their oxytocin appositions, the data have been combined. Ninety-nine of the 124 (i.e. 79.8%; n=5 rats) identified ileum-projecting DMV neurons received oxytocin-positive appositions.

OXT axons appose glucoprivation-responsive DMV neurons

Fourteen rats were treated with 2-DG to induce Fos-immunoreactivity in glucoprivation-sensitive DMV neurons. Five control rats received saline injections.

In eight rats treated with 2-DG, we confirmed that Fos activation in the DVC was not due to cardiovascular changes as mean arterial pressure (MAP) and heart rate were unaffected by 2-DG administration (Table 2).

Table 2.

Effect of 2-Deoxyglucose on Mean Arterial Pressure (MAP) and Heart Rate (HR)

| Male (n=4) | Female (n=4) | |

|---|---|---|

| Resting MAP (mmHg) | 112.5±7.1 | 120.5±2.9 |

| MAP after 2-DG | ||

| 5 min | 111.6±10.0 | 119.7±2.0 |

| 30 min | 113.4±7.4 | 117.1±7.3 |

| 60 min | 110.1±11.3 | 117.6±4.9 |

| Resting HR (bpm) | 384.2±19.9 | 386.5±19.5 |

| HR after 2-DG | ||

| 5 min | 384.9±27.5 | 390.9±26.8 |

| 30 min | 381.7±30.8 | 382.5±11.1 |

| 60 min | 365.4±22.5 | 383.8±10.0 |

Administration of 2-DG induced Fos expression in some DMV neurons (Figure 2D–G). NTS and ventral medullary neurons also expressed Fos after 2-DG, as previously reported43. In saline-treated rats, Fos-immunoreactivity was rare in the DMV, NTS and ventral medulla.

In sections stained for OXT, Fos and ChAT, Fos was found in cholinergic and non-cholinergic DMV neurons. Fos/ChAT DMV neurons (i.e., glucoprivation-sensitive vagal motor neurons) were concentrated in the medial DMV beneath AP (Figures 2D–E) but occasionally occurred rostral and caudal (Figure 2G) to AP. 2-DG-responsive non-cholinergic DMV neurons were usually located at and caudal to calamus scriptorius.

OXT-immunoreactive axons innervated a subset of the ChAT/Fos DMV neurons (Figures 2D–G), which comprised 76 of 173 (i.e. 43.9%, n=5) Fos-positive neurons. These 2-DG-responsive neurons received close appositions from both fine OXT-positive axons with small varicosities (Figure 2F) and thick axons with large varicosities (Figures 2E, 2G). Glucoprivation-sensitive neurons with OXT-immunoreactive appositions were concentrated in the subpostremal DMV (Figures 2E–F) but also occurred in DMV regions rostral and caudal (Figure 2G) to AP. TH-positive neurons were amongst the population of Fos/ChAT DMV neurons that received OXT appositions. Despite the high background labeling in sections stained for these four antigens, 3 of 83 (n=3) 2-DG responsive DMV neurons were identified as both Fos and TH-Immunoreactive.

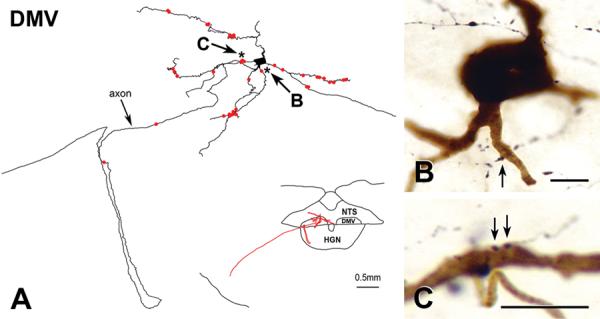

OXT axons appose juxtacellularly-labelled DMV neurons

In 5 rats, a total of 6 DMV neurons responding to antidromic vagal stimulation were juxtacellularly-labeled. Labeling was heavy in three neurons, moderate in two and light in one neuron. Two cell bodies occurred roughly at calamus scriptorius, one soma lay between calamus scriptorius and mid-AP. The remaining three were located around mid-AP with two in lateral DMV. All of the well-labeled neurons had extensive dendritic trees that extended into the NTS (Figure 3A).

FIGURE 3. OXT-immunoreactive innervation of juxtacellularly labelled DMV neurons.

A: Reconstruction of a juxtacellularly-labeled DMV neuron. The map in the lower right shows that the cell body of the neuron lay just rostral to calamus scriptorius, a region with dense OXT innervation. A labeled dendrite extends into the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS); other dendrites extend medially and laterally. The axon loops through the hypoglossal nucleus (HGN) before traveling toward the ventrolateral medullary surface. Bar for map, 0.5 mm. The juxtacellularly-labeled neuron received 27 OXT appositions (red dots) on its proximal and distal dendrites. Two OXT appositions occurred on the axon. Stars, appositions in 3B and 3C. B: Starred apposition (black) indicated by arrow B in 3A closely apposes a ventrally-projecting proximal dendrite (brown) about 15 μm from the cell body. Bar, 10 μm. C: Starred appositions (black) indicated by arrow C in 3A closely appose a laterally-projecting dendrite (brown). Bar, 10 μm.

OXT-immunoreactive axons closely apposed the dendrites of all labeled neurons (e.g., Figure 3). Appositions occurred on proximal (Figure 3B,C) and distal dendrites. Heavy labeling in five neurons made it impossible to determine whether they received axosomatic appositions. The soma of the lightly filled neuron received several OXT-immunoreactive appositions. Two OXT-containing varicosities also appeared to contact the axon of the best filled neuron (Figure 3A).

DISCUSSION

In the present manuscript, we provide the first detailed, systematic investigation of the OXT-immunoreactive innervation of identified DMV neurons involved in the control of GI function. Here, we show a heterogeneous distribution of OXT axons throughout the DMV, with more innervation caudally and laterally, and asymmetric OXT synapses with small clear and large granular vesicles on DMV cell bodies and dendrites.

We also provide the first anatomical evidence for a direct OXT input to identified GI-projecting DMV neurons.

Specifically, we show 1) OXT axons closely apposing corpus-projecting, ileum-projecting and juxtacellularly-labeled DMV neurons, 2) OXT appositions on ChAT and ChAT/TH DMV neurons as well as TH-containing NTS neurons and 3) OXT appositions on glucoprivation-responsive DMV neurons with and without ChAT-immunoreactivity. These OXT appositions probably represent synaptic input. Studies on central autonomic circuits that have directly correlated close appositions and synapses show that 50% of terminals closely apposing neurons at the LM level form synapse at the EM level44.

Physiological role of OXT in the DVC

OXT is synthesized by magnocellular and parvocellular neurons in the paraventricular (PVN) and supraoptic nuclei of the hypothalamus. The magnocellular neurons are part of the hypothalamic-neurohypophyseal axis and their release of OXT accounts for its hormonal effects on a variety of functions, including enhancement of prolactin release and milk ejection. The parvocellular oxytocinergic PVN neurons are part of the HPA axis and innervate brainstem autonomic neurons45. In rat DVC, OXT axons of PVN origin are present at birth and increase severalfold into adulthood21. In adult rats, the density of OXT-immunoreactive axons has been reported as far lower in the DMV than in the dorsal NTS46; but we have not replicated this finding as we found a homogeneous distribution of OXT-immunoreactive varicosities in the NTS with no regional variation16. The present work confirms and extends our previous observations, showing OXT innervation throughout the DVC with a homogenous distribution of axons in the NTS but denser innervation in the subpostremal and lateral DMV than in other DMV regions.

The occurrence of descending OXT-containing PVN-to-DMV projections suggests that hypothalamic OXT neurons regulate visceral targets, including the GI tract. Electrophysiological studies support this suggestion. OXT excites subpopulations of putative DMV neurons47, which lie in regions containing OXT binding sites/receptors29. OXT also selectively increases the probability of glutamate release onto NTS neurons from vagal afferents16, suggesting that OXT may affect DMV neurons through presynaptic mechanisms.

Consistent with these studies, OXT-releasing PVN inputs to the NTS and DMV decrease gastric motility and increase secretion (reviewed by19). This OXT pathway, which activates brainstem vagal motor neurons to induce profound inhibition of GI motility, is tonically active20,25; and intracerebroventricular administration of OXT antagonists increases baseline gastric motility by affecting DMV neurons20.

OXT projections to the DVC are also involved in controlling ingestive behaviors, although some data appear to downplay the role of OXT since oxytocin-deficient mice are still susceptible to the anorexigenic effect of CCK and dfenfluramine48. Plasma OXT concentrations increase following a meal22 and intracerebroventricular OXT reduces food intake. This effect can be blocked by pretreatment with OXT antagonists26, which also decreases CCK-induced c-fos activation in brainstem vagal areas15. The present study provides anatomical evidence for the potential OXT's role in ingestion, showing that OXT-containing varicosities closely appose DMV neurons that are activated by 2-DG-induced glucoprivation. Previous studies suggest that, i n t h e D V C, only A2/C2 catecholaminergic neurons express Fos after 2-DG (reviewed in49). However, our data reveal that a subset of ChAT-immunoreactive DMV neurons is 2-DG-responsive and that OXT-immunoreactive axons innervate some glucoprivation-sensitive neurons. In triple-labeling studies, some of our 2DG-activated neurons with oxytocin appositions were TH-positive, indicating that they were indeed A2/C2 neurons. Oxytocin synapses have already been demonstrated on C2 neurons in the DMV50. Hence, part of the hypothalamic control of GI functions may involve synaptic connections between OXT axons and DVC catecholamine as well as noncatecholamine neurons.

The present study demonstrates an OXT input to DMV neurons that probably reflexly control the GI tract4. Reflex gastric accommodation to a meal is achieved via vagally-mediated relaxation of the proximal stomach, allowing the efficient transport of ingesta into the stomach without an increase in intragastric pressure. Our data showing a widespread OXT innervation of DVC areas that control GI functions provide the anatomical substrate for a direct influence of OXT in modulating vagal GI-regulating circuitry.

Possible pathophysiological role of OXT in DVC

Many pathophysiological stimuli induce alterations of GI motility. Among these, stress is very important in the development of GI diseases, including motility disorders such as functional dyspepsia (FD). Stress-related alterations of gastric motility are among the main pathophysiological mechanisms for generating dyspeptic symptoms; and most FD patients associate stressful events with initiation or exacerbation of their symptoms34–37. In animals as well as healthy humans, acute stress decreases gastric emptying by inducing uncoordinated gastric motility patterns and chronic stress induces FD-like symptoms33,51–56. These observations support a pathological role for stress in the dysmotility that characterizes FD, with some evidence pointing towards impairment of the vagal sensory-motor loop that reciprocally connects the gut with the CNS. The observations that almost 50% of FD patients have disturbed efferent vagal functions and abnormal intragastric meal distribution with preferential accumulation in the distal stomach emphasize the involvement of the vagus57–59.

Central OXT plays an important role in regulating social behavior and has anti-stress and anti-anxiety effects31. A demonstrated anti-stress effect of central OXT is reversal of the gastric dysmotility resulting from acute stress; conversely, OXT antagonists reverse adaptation to chronic repeated homotypic stress33. While the mechanism underlying the anti-stress effects of OXT are still under investigation, it is clear that OXT acts centrally to reverse the stress-induced delay in gastric emptying by restoring co-ordinated gastric motility patterns.

During stress, corticotrophin releasing factor (CRF) released from hypothalamic neurons also profoundly disrupts GI motility (reviewed by54) and the DVC is a likely site of action63. The anxiolytic and anti-stress effects of OXT may be mediated by its inhibitory influence on CRF expression in the brain. These two peptides could interact in the DMV since axons from hypothalamic CRF and OXT neurons innervate the DMV15. Indeed, our electrophysiological results indicate that CRF uncovers an OXT-mediated modulation of otherwise unresponsive GABAergic currents between NTS and DMV64.

Because FD is exacerbated by stress, the PVN-DVC projections that use OXT (and CRF) may undergo stress-induced rearrangements that impair function. In fact, when autonomic-emotional neurocircuits are assembling in neonatal and juvenile rats, they are more susceptible to environmental influences65,66. For example, the increased maternal care induced by brief daily periods of separation facilitates the development of hypothalamo-gastric preautonomic circuits65; and brief pharmacological manipulation produces FD-like symptoms67.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates the anatomical substrate that underpins the important role of OXT in the DVC for regulating GI functions, particularly in response to stress. Our current findings mesh with the concept that autonomic homeostatic neurocircuits, including those controlling GI function, are extremely malleable. A variety of influences, such as stress, feeding, time of day and activity, can rearrange and modulate synaptic interactions, with profound effects on visceral function.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Carolyn Martin, Natalie Fenwick and Lee Travis provided valuable technical assistance. We would also like to thank Cesare M. and Zoraide Travagli and W. Nairn Browning for support and encouragement.

Grant Support: Grants from the National Health & Medical Research Council of Australia to ILS (Project Grant #480414, Principal Research Fellowship #229921), a Biomedical Research Collaboration Grant from the Wellcome Trust UK to DJ and ILS (067996/Z/02/Z), a grant from the British Heart Foundation to DJ supporting DOK, NIH NIDDK 55530 to AT and NIH NIDDK 078364 to KNB.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES Ida J. Llewellyn-Smith, Kirsteen N. Browning and R. Alberto Travagli designed the research study and wrote the paper.

Ida J. Llewellyn-Smith, Daniel O. Kellett, David Jordan

Kirsteen N. Browning and R. Alberto Travagli performed the research.

No COI for any of the authors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andresen MC, Kunze DL. Nucleus tractus solitarius - gateway to neural circulatory control. Annual Review of Physiology. 1994;56:93–116. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.56.030194.000521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Travagli RA, Hermann GE, Browning KN, Rogers RC. Brainstem circuits regulating gastric function. Annu Rev Physiol. 2006;68:279–305. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.68.040504.094635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hornby PJ. Receptors and transmission in the brain-gut axis. II. Excitatory amino acid receptors in the brain-gut axis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001;280:G1055–G1060. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.280.6.G1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Browning KN, Travagli RA. Plasticity of vagal brainstem circuits in the control of gastric function. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:1154–1163. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01592.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andresen MC, Paton JFR. The nucleus of the solitary tract: Processing information from viscerosensory afferents. In: Llewellyn-Smith IJ, Verberne AJM, editors. Central Regulation of Autonomic Functions. Second Edition Oxford University Press; New York: 2011. pp. 23–46. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bailey TW, Hermes SM, Andresen MC, Aicher SA. Cranial visceral afferent pathways through the nucleus of the solitary tract to caudal ventrolateral medulla or paraventricular hypothalamus: target-specific synaptic reliability and convergence patterns. J Neurosci. 2006;26:11893–11902. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2044-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonham AC, Chen CY, Sekizawa S, Joad JP. Plasticity in the nucleus tractus solitarius and its influence on lung and airway reflexes. J Appl Physiol. 2006;101:322–327. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00143.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jin YH, Bailey TW, Li BY, Schild JH, Andresen MC. Purinergic and vanilloid receptor activation releases glutamate from separate cranial afferent terminals in nucleus tractus solitarius. J Neurosci. 2004;24:4709–4717. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0753-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fox EA, Powley TL. Longitudinal columnar organization within the dorsal motor nucleus represents separate branches of the abdominal vagus. Brain Res. 1985;341:269–282. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)91066-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shapiro RE, Miselis RR. The central organization of the vagus nerve innervating the stomach of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1985;238:473–488. doi: 10.1002/cne.902380411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Norgren R, Smith GP. Central distribution of subdiaphragmatic vagal branches in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1988;273:207–223. doi: 10.1002/cne.902730206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berthoud HR, Carlson NR, Powley TL. Topography of efferent vagal innervation of the rat gastrointestinal tract. Am J Physiol. 1991;260:R200–R207. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1991.260.1.R200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Voorn P, Buijs RM. An immuno-electronmicroscopical study comparing vasopressin, oxytocin, substance P and enkephalin containing nerve terminals in the nucleus of the solitary tract of the rat. Brain Res. 1983;270:169–173. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)90809-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higa KT, Mori E, Viana FF, Morris M, Michelini LC. Baroreflex control of heart rate by oxytocin in the solitary-vagal complex. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2002;282:R537–R545. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00806.2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blevins JE, Eakin TJ, Murphy JA, Schwartz MW, Baskin DG. Oxytocin innervation of caudal brainstem nuclei activated by cholecystokinin. Brain Res. 2003;993:30–41. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peters JH, McDougall SJ, Kellett DO, Jordan D, Llewellyn-Smith IJ, Andresen MC. Oxytocin enhances cranial visceral afferent synaptic transmission to the solitary tract nucleus. J Neurosci. 2008;28:11731–11740. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3419-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saper CB, Loewy AD, Swanson LW, Cowan WM. Direct hypothalamo-autonomic connections. Brain Res. 1976;117:305–312. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(76)90738-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Swanson LW, Kuypers HG. The paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus: cytoarchitectonic subdivisions and organization of projections to the pituitary, dorsal vagal complex, and spinal cord as demonstrated by retrograde fluorescence double-labeling methods. J Comp Neurol. 1980;194:555–570. doi: 10.1002/cne.901940306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Richard P, Moos F, Freund-Mercier MJ. Central effects of oxytocin. Physiol Rev. 1991;71:331–370. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1991.71.2.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flanagan LM, Olson BR, Sved AF, Verbalis JG, Stricker EM. Gastric motility in conscious rats given oxytocin and an oxytocin antagonist centrally. Brain Res. 1992;578:256–260. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90255-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rinaman L. Oxytocinergic inputs to the nucleus of the solitary tract and dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus in neonatal rats. J Comp Neurol. 1998;399:101–109. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19980914)399:1<101::aid-cne8>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Verbalis JG, McCann MJ, McHale CM, Stricker EM. Oxytocin secretion in response to cholecystokinin and food: differentiation of nausea from satiety. Science. 1986;232:1417–1419. doi: 10.1126/science.3715453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tribollet E, Charpak S, Schmidt A, Dubois-Dauphin M, Dreifuss JJ. Appearance and transient expression of oxytocin receptors in fetal, infant, and peripubertal rat brain studied by autoradiography and electrophysiology. J Neurosci. 1989;9:1764–1773. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-05-01764.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raggenbass M, Dreifuss JJ. Mechanism of action of oxytocin in rat vagal neurones: induction of a sustained sodium-dependent current. J Physiol. 1992;457:131–142. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fujimiya M, Inui A. Peptidergic regulation of gastrointestinal motility in rodents. Peptides. 2000;21:1565–1582. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(00)00313-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olson BR, Drutarosky MD, Chow MS, Hruby VJ, Stricker EM, Verbalis JG. Oxytocin and an oxytocin agonist administered centrally decrease food intake in rats. Peptides. 1991;12:113–118. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(91)90176-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Siaud P, Puech R, Assenmacher I, Alonso G. Microinjection of oxytocin into the dorsal vagal complex decreases pancreatic insulin secretion. Brain Res. 1991;546:190–194. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91480-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dreifuss JJ, Raggenbass M, Charpak S, Dubois-Dauphin M, Tribollet E. A role of central oxytocin in autonomic functions: its action in the motor nucleus of the vagus nerve. Brain Res Bull. 1988;20:765–770. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(88)90089-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tribollet E, Barberis C, Jard S, Dubois-Dauphin M, Dreifuss JJ. Localization and pharmacological characterization of high affinity binding sites for vasopressin and oxytocin in the rat brain by light microscopic autoradiography. Brain Res. 1988;442:105–118. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)91437-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Windle RJ, Kershaw YM, Shanks N, Wood SA, Lightman SL, Ingram CD. Oxytocin attenuates stress-induced c-fos mRNA expression in specific forebrain regions associated with modulation of hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal activity. J Neurosci. 2004;24:2974–2982. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3432-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neumann ID. Brain oxytocin: a key regulator of emotional and social behaviours in both females and males. J Neuroendocrinol. 2008;20:858–865. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2008.01726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zheng J, Babygirija R, Bulbul M, Cerjak D, Ludwig K, Takahashi T. Hypothalamic oxytocin mediates adaptation mechanism against chronic stress in rats. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2010;299:G946–G953. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00483.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Babygirija R, Zheng J, Ludwig K, Takahashi T. Central oxytocin is involved in restoring impaired gastric motility following chronic repeated stress in mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010;298:R157–R165. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00328.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Camilleri M, Malagelada JR, Kao PC, Zinsmeister AR. Gastric and autonomic responses to stress in functional dyspepsia. Dig Dis Sci. 1986;31:1169–1177. doi: 10.1007/BF01296514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Geeraerts B, Vandenberghe J, Van OL, Gregory LJ, Aziz Q, Dupont P, Demyttenaere K, Janssens J, Tack J. Influence of experimentally induced anxiety on gastric sensorimotor function in humans. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1437–1444. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thumshirn M. Pathophysiology of functional dyspepsia. Gut. 2002;51(Suppl 1):i63–i66. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.suppl_1.i63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tack J, Lee KJ. Pathophysiology and treatment of functional dyspepsia. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:S211–S216. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000156109.97999.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jones GA, Llewellyn-Smith IJ, Jordan D. Physiological, pharmacological, and immunohistochemical characterisation of juxtacellularly labelled neurones in rat nucleus tractus solitarius. Auton Neurosci. 2002;98:12–16. doi: 10.1016/s1566-0702(02)00022-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jeggo RD, Kellett DO, Wang Y, Ramage AG, Jordan D. The role of central 5-HT3 receptors in vagal reflex inputs to neurones in the nucleus tractus solitarius of anaesthetized rats. J Physiol. 2005;566:939–953. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.085845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Llewellyn-Smith IJ, DiCarlo SE, Collins HL, Keast JR. Enkephalin-immunoreactive interneurons extensively innervate sympathetic preganglionic neurons regulating the pelvic viscera. J Comp Neurol. 2005;488:278–289. doi: 10.1002/cne.20552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Llewellyn-Smith IJ, Schreihofer AM, Guyenet PG. Distribution and amino acid content of enkephalin-immunoreactive inputs onto juxtacellularly labelled bulbospinal barosensitive neurons in rat rostral ventrolateral medulla. Neuroscience. 2001;108:307–322. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00415-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Llewellyn-Smith IJ, Martin CL, Arnolda LF, Minson JB. Retrogradely transported CTB-saporin kills sympathetic preganglionic neurons. NeuroReport. 1999;10:307–312. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199902050-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ritter S, Llewellyn-Smith IJ, Dinh TT. Subgroups of hindbrain catecholamine neurons are selectively activated by 2-deoxy-D-glucose induced metabolic challenge. Brain Res. 1998;805:41–54. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00655-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pilowsky P, Llewellyn-Smith IJ, Lipski J, Chalmers J. Substance P immunoreactive boutons form synapses with feline sympathetic preganglionic neurons. J Comp Neurol. 1992;320:121–135. doi: 10.1002/cne.903200109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sawchenko PE, Swanson LW. Immunohistochemical identification of neurons in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus that project to the medulla or to the spinal cord in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1982;205:260–272. doi: 10.1002/cne.902050306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Siaud P, Denoroy L, Assenmacher I, Alonso G. Comparative immunocytochemical study of the catecholaminergic and peptidergic afferent innervation to the dorsal vagal complex in rat and guinea pig. J Comp Neurol. 1989;290:323–335. doi: 10.1002/cne.902900302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Raggenbass M, Dubois-Dauphin M, Charpak S, Dreifuss JJ. Neurons in the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve are excited by oxytocin in the rat but not in the guinea pig. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:3926–3930. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.11.3926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mantella RC, Rinaman L, Vollmer RR, Amico JA. Cholecystokinin and D-fenfluramine inhibit food intake in oxytocin-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2003;285:R1037–R1045. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00383.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ritter S, Dinh TT, Li AJ. Hindbrain catecholamine neurons control multiple glucoregulatory responses. Physiol Behav. 2006;89:490–500. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Siaud P, Denoroy L, Assenmacher I, Alonso G. Comparative immunocytochemical study of the catecholaminergic and peptidergic afferent innervation to the dorsal vagal complex in rat and guinea pig. J Comp Neurol. 1989;290:323–335. doi: 10.1002/cne.902900302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gue M. Effect of stress on gastrointestinal motility. In: Johnson LR, Barrett KE, Merchant JL, Ghishan FK, Said HM, Wood JD, editors. Physiology of the Gastrointestinal Tract. Academic Press; London: 2006. pp. 781–790. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nakade Y, Tsuchida D, Fukuda H, Iwa M, Pappas TN, Takahashi T. Restraint stress delays solid gastric emptying via a central CRF and peripheral sympathetic neuron in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;288:R427–R432. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00499.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tache Y, Martinez V, Million M, Wang L. Stress and the gastrointestinal tract III. Stress-related alterations of gut motor function: role of brain corticotropin-releasing factor receptors. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001;280:G173–G177. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.280.2.G173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tache Y, Bonaz B. Corticotropin-releasing factor receptors and stress-related alterations of gut motor function. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:33–40. doi: 10.1172/JCI30085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nakade Y, Tsuchida D, Fukuda H, Iwa M, Pappas TN, Takahashi T. Restraint stress augments postprandial gastric contractions but impairs antropyloric coordination in conscious rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;290:R616–R624. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00161.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bulbul M, Babygirija R, Ludwig K, Takahashi T. Central oxytocin attenuates augmented gastric postprandial motility induced by restraint stress in rats. Neurosci Lett. 2010;479:302–306. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.05.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Troncon LE, Thompson DG, Ahluwalia NK, Barlow J, Heggie L. Relations between upper abdominal symptoms and gastric distension abnormalities in dysmotility like functional dyspepsia and after vagotomy. Gut. 1995;37:17–22. doi: 10.1136/gut.37.1.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Holtmann G, Goebell H, Jockenhoevel F, Talley NJ. Altered vagal and intestinal mechanosensory function in chronic unexplained dyspepsia. Gut. 1998;42:501–506. doi: 10.1136/gut.42.4.501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tack J. Neurophysiologic mechanisms of gastric reservoir function. In: Johnson LR, Barrett KE, Merchant JL, Ghishan FK, Said HM, Wood JD, editors. Physiology of the Gastrointestinal Tract. Academic Press; London: 2006. pp. 927–934. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bisschops R, Tack J. Dysaccommodation of the stomach: therapeutic nirvana? Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2007;19:85–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2006.00863.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Grundy D, Gharib-Naseri MK, Hutson D. Role of nitric oxide and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide in vagally mediated relaxation of the gastric corpus in the anaesthetized ferret. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1993;43:241–246. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(93)90330-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tack J, Caenepeel P, Piessevaux H, Cuomo R, Janssens J. Assessment of meal induced gastric accommodation by a satiety drinking test in health and in severe functional dyspepsia. Gut. 2003;52:1271–1277. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.9.1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lewis MW, Hermann GE, Rogers RC, Travagli RA. In vitro and in vivo analysis of the effects of corticotropin releasing factor on rat dorsal vagal complex. J Physiol. 2002;543:135–146. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.019281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Browning KN, Travagli RA. In vitro studies. Gastroenterology Digestive Diseases Week; San Diego (CA): 2008. Modulation of brainstem vagal inhibitory circuits in response to application of CRF and oxytocin. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Banihashemi L, Rinaman L. Repeated brief postnatal maternal separation enhances hypothalamic gastric autonomic circuits in juvenile rats. Neuroscience. 2010;165:265–277. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.09.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Oreland S, Gustafsson-Ericson L, Nylander I. Short- and long-term consequences of different early environmental conditions on central immunoreactive oxytocin and arginine vasopressin levels in male rats. Neuropeptides. 2010;44:391–398. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liu LS, Winston JH, Shenoy MM, Song GQ, Chen JD, Pasricha PJ. A rat model of chronic gastric sensorimotor dysfunction resulting from transient neonatal gastric irritation. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:2070–2079. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Llewellyn-Smith IJ, Martin CL, Fenwick NM, DiCarlo SE, Lujan HL, Schreihofer AM. VGLUT1 and VGLUT2 innervation in autonomic regions of intact and transected rat spinal cord. J Comp Neurol. 2007;503:741–767. doi: 10.1002/cne.21414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Llewellyn-Smith IJ, Pilowsky P, Minson JB, Chalmers J. Synapses on axons of sympathetic preganglionic neurons in rat and rabbit spinal cord. J Comp Neurol. 1995;354:193–208. doi: 10.1002/cne.903540204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fenwick NM, Martin CL, Llewellyn-Smith IJ. Immunoreactivity for cocaine-and amphetamine-regulated transcript in rat sympathetic preganglionic neurons projecting to sympathetic ganglia and the adrenal medulla. J Comp Neurol. 2006;495:422–433. doi: 10.1002/cne.20870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]