Abstract

The goal of this study is to estimate the prevalence of Metabolic Syndrome (MetS), together with its components and correlates, among elderly Russians. Our population-based sample included randomly selected residents of Moscow aged 55 and older: 955 women with an average age of 67.6, and 833 men with an average age of 68.9. MetS was defined according to NCEP-ATPIII. The prevalence of MetS was found to be 41.7% in women and 26.8% in men. It tended to decrease with age in men, but not in women. MetS was inversely related to education in women, but not in men. The most prevalent individual components of MetS were as follows: hypertension (64.4%), abdominal obesity (55%), and decreased HDL C (46%) for women; and hypertension (71%) and fasting hyperglycemia (35.2%) for men. An elevated level of TG was the rarest MetS component, affecting 23.5% of women and 22.1% of men. The higher female prevalence of MetS was attributable to abdominal obesity. MetS was found to be associated with markers of insulin resistance, low-grade inflammation, and insufficient fibrinolysis. Although the metabolic burden is an important contributor to high levels of ill-health and cardiovascular mortality among elderly Russians (especially women), it does not explain why cardiovascular mortality is much higher in Russia than in other industrialized countries.

Keywords: elderly, metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance, C-reactive protein, coagulation and fibrinolysis, Russia

1. Introduction

The clustering of several metabolic abnormalities (central obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, impaired glucose metabolism) in a single person, known as metabolic syndrome (MetS), is associated with an increased risk of diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease (CVD), and all-cause mortality (Haffner et al., 1992; Isomaa et al., 2003; Galassi et al., 2006; Gami et al., 2007). Surveys have indicated that MetS affects large portions of the population across the industrialized world (Cameron et al., 2004; Tzou et al., 2005; He et al., 2006; Gami et al., 2007). While the prevalence of MetS has generally been shown to vary from between one-fifth and one-fourth of the adult population in most industrialized countries, the syndrome has been found to affect more than one-third of adults in some US and European samples (Balkau et al., 2002; Ford et al, 2002; Hildrum et al., 2007). These differences have been attributed to varying behavioral and epidemiological patterns in different countries, and (to some extent) to the use of different MetS definitions and different sampling and recruitment schemes in individual studies (Expert Panel, 2001; Balkau et al., 2002; Grundy et al., 2005; The IDF Consensus Worldwide Definition, 2006). It is, however, clear that MetS is a highly prevalent condition, and represents a global health concern (Isomaa et al., 2003; Eckel et al., 2005).

A study of MetS in Russia is of special interest due to the extremely high levels of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in this country (Meslé, 2004). In 2009, life expectancy at birth was 74.7 years for Russian women and 62.7 years for Russian men, and the age-standardized (European population standard) mortality rates per 100,000 were 927 for men and 525 for women (The Demographic Yearbook of Russia, 2010). The latter figures are more than four times higher than those for the original member states of the European Union (Health for All Database, 2011). In addition, the Russian population (especially women) experience high rates of ill health and disability at older ages (Andreev et al., 2003).

Reliable information about the spread of the principal risk factors in the general population is essential for addressing health challenges. So far, very little is known about MetS in Russia. We know of only one population-based study that contains information about the prevalence of MetS (Sidorenkov et al., 2010; Sidorenkov, Nilssen, Grjibovski, 2010). This work was conducted in the city of Arkhangelsk in northwestern Russia, and included relatively young subjects aged 18 and older (41.6 on average), most of whom were working or in education. The prevalence of MetS (NCEP criteria) was found to be relatively low: nearly 20% in women and 12% in men.

The present study complements the prior study in three respects. First, it looks at an older group of the normal population that is exposed to higher cardiovascular risk and experiences higher and less varying by age prevalence of metabolic abnormalities. Second, we assess the links between MetS and certain inflammation and haemostatic markers that were not examined in the Arkhangelsk study. Third, our sample originates from the population of Moscow, a metropolitan region with somewhat lower level of total and cardiovascular mortality as compared to Arkhangelsk (Vallin et al., 2005).

Our study provides estimates of MetS and its components among older men and women in Russia, and informs about associations between MetS and the biomarkers of insulin resistance, prothrombotic status, and inflammation.

2. Data and Methods

2.1. Sample

This study relies on baseline survey data from “Stress, Aging, and Health in Russia” (SAHR), an ongoing prospective population-based cohort study of Muscovites aged 55 and older. The study is jointly conducted by the State Research Center for Preventive Medicine (Moscow, Russian Federation), the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research (Rostock, Germany) and Duke University (Durham, USA). The study protocols were approved by the Ethics Committee of the State Research Center for Preventive Medicine in Moscow and the Institutional Review Board at Duke University in Durham, USA. Before being interviewed and medically tested, all of the participants in the SAHR study were fully informed about the survey program, and were asked to sign participation agreement forms. The sampling and recruitment procedures, as well as the study design, have been described in detail elsewhere (Shkolnikova et al., 2009).

The SAHR study participants were randomly selected from epidemiological cohorts (such as Lipid Research Clinics and Monica cohorts) who were first screened in the 1970s to the 1990s, as well as from medical insurance registers. The SAHR baseline survey was conducted between December 1, 2006 and June 30, 2009. The final response rate was 66%. The sample of the baseline survey included 1,800 subjects (961 women and 839 men). The characteristics of the sample are described later in the text.

Face-to-face interviews and extensive medical testing were administered at the hospital or at home according to the study protocol (Shkolnikova et al., 2009). The biomedical protocol included anthropometric measurements, office blood pressure, blood lipid and glucose tests, and a broad range of other biochemical and clinical measurements (Shkolnikova et al., 2009). One or more MetS measurements were missing for only 12 subjects (0.7%). Correspondingly, a MetS assessment and related analyses were performed on a sample of 1 788 subjects.

2.2. Definition of metabolic syndrome

MetS was defined in accordance with the definition provided by the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III (NCEP-ATPIII) (Executive Summary, 2001). Individuals with MetS suffer from at least three of the following five conditions: (1) abdominal obesity (waist circumference >88 cm for women, and >102 cm for men); (2) elevated blood pressure (BP): systolic BP ≥130 mm Hg or diastolic BP ≥ 85 mm Hg or ongoing antihypertensive treatment; (3) triglycerides (TG) level ≥1.7 mmol/L; (4) high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL C) <1.0 mmol/L for men, and <1.3 mmol/L for women, and (5) fasting glucose ≥6.1 mmol/L.

2.3. Laboratory tests

A blood sample was drawn from the median cubital vein after overnight fasting. Sera or plasma were obtained by low-speed centrifugation at 4°C, and were aliquoted for subsequent testing. Serum total cholesterol (C), TG and HDL C values were measured using standard enzymatic methods. Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL C) was calculated according to Freidewald’s equation, if TG level did not exceed 4.5 mmol/L. The glucose level in serum was determined by the glucose oxidase method, and glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) was measured in the whole blood samples using high-performance liquid chromatography; levels of less than 6% were accepted as normal.

Fasting insulin levels were measured in serum as total immunoreactive insulin by radioimmunoassay (RIA) using IRMA kits. Hyperinsulinemia was estimated as an insulin level that exceeded upper quartile cut-off points: 11.6 for men and 13.2 μU/mL for women. Insulin resistance was quantified using a Homeostasis Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR) index equal to (fasting blood glucose, mmol/L)*(serum insulin, μU/mL)/22.5 (Matthew et al., 1985). Insulin resistance was defined as HOMA-IR levels exceeding 3.24 for men and 3.55 for women, which corresponded to upper quartile cut-off points.

Fibrinogen in citrate plasma was determined using the Clauss method. Hyperfibrinogenemia was defined as fibrinogen levels exceeding 4.0 g/L. Activity of fibrinolysis was estimated as a time of spontaneous lysis of euglobulin fraction clot (ECLT). Hypofibrinolysis was defined as ECLT longer than 240 min.

High-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT) were considered markers of low-grade inflammation. hsCRP concentration was measured by means of particle-enhanced rate immunonephelometry using N Latex CRP monoreagent. Elevated hsCRP was defined as hsCRP>3.0 mg/L. IL-6 was determined by the quantitative sandwich ELISA technique. Elevated IL-6 was defined as IL-6>4.0 pg/mL. Gamma- (GGT) activity was measured by the colorimetric kinetic method. Elevated GGT elevation was defined as GGT>49 Units/L.

2.4. Statistical analysis

The sex-specific characteristics of the sample were obtained by means of simple tabulations and descriptive statistics. Logistic regression with age under control was used to detect the MetS components responsible for sex difference in MetS, as well as for linking MetS with demographic and biochemical variables. In regressions, relative risk was expressed by the age-adjusted odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Statistical computations were executed in Stata 10.0. MS Excel 2003 was used for building figures.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the sample

Table 1 presents the socio-demographic, behavioral, and biomedical characteristics of the sample. The number of women exceeded the number of men in the sample by nearly 7%. All of the subjects were aged 55 to 92, with mean ages of around 68 for women and 69 for men. Nearly half of the sample had a higher level of education, while the other half had secondary or lower levels of education. The percentage of the sample with higher education was above that of the general population of Moscow (35%) and of the whole Russian Federation (13%), according the last census (Vserossiskaya Perepis Naseleniya, 2011).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the sample under study#

| Women | Men | p-value for sex difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics: | |||

| Number of subjects | 955 | 833 | - |

| Percentage, % | 53.4 | 46.6 | - |

| Mean age, years | 67.6 (7.3)§ | 68.9 (8.2) | <0.001 |

| Education, %: | |||

| Secondary and lower | 49.1 | 53.1 | NS& |

| Higher | 50.9 | 46.9 | NS |

| Smoking, %: | |||

| Current | 8.5 | 25.5 | <0.0001 |

| Former | 11.1 | 41.0 | <0.0001 |

| Never | 80.4 | 33.5 | <0.0001 |

| Alcohol use: | |||

| Ethanol consumption, L/year | 0.70 (1.99) | 2.81 (6.23) | <0.0001 |

| Frequency, times/month | 1.80 (2.44) | 6.96 (9.12) | <0.0001 |

| Physical measurements: | |||

| Height, cm | 158.9 (6.06) | 171.6 (6.8) | <0.0001 |

| Weight, kg | 74.4 (13.4) | 81.3 (14.8) | <0.0001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 29.5 (5.1) | 27.6 (4.5) | <0.0001 |

| Waist, cm | 90.3 (11.8) | 96.6 (12.7) | <0.0001 |

| Systolic BP, mm Hg | 139.9 (22.9) | 144.6 (23.7) | <0.0001 |

| Diastolic BP, mm Hg | 79.5 (12.3) | 83.4 (12.9) | <0.0001 |

| Biochemical tests: | |||

| Cholesterol total, mmol/L | 6.3 (1.2) | 5.6 (1.1) | <0.0001 |

| Triglycerides, mmol/L | 1.38 (0.75) | 1.33 (0.74) | NS |

| HDL cholesterol, mmol/L | 1.34 (0.32) | 1.22 (0.32) | <0.0001 |

| LDL cholesterol, mmol/L | 4.3 (1.1) | 3.8 (1.0) | <0.0001 |

| Glucose, mmol/L | 6.0 (1.6) | 6.2 (1.7) | <0.005 |

| Diseases: | |||

| History of diabetes, % | 12.3 | 10.4 | NS |

| History of myocardial infarction, % | 5.3 | 14.8 | <0.0001 |

n=1,788.

Standard deviations are given in parentheses.

Not significant.

A marked gender difference was found in smoking and alcohol use, with women being far less likely than men to consume alcohol and tobacco. While women had higher total C and were more likely to be overweight than men, men had higher BP and were more likely to have a history of myocardial infarction than women. Among women, 80.1% were found to be overweight (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2) (compared to 69.8% of men). Elevated BP (systolic BP≥140 mm Hg and/or diastolic BP≥90 mm Hg) was observed in 58.6% of men (compared to 48.0% of women).

3.2. Metabolic syndrome in demographic dimensions

Table 2 shows the prevalence rates of MetS and its five components in relation to gender and age. For all ages combined, the prevalences were computed both with the actual age structure of the sample and with Segi’s world population standard. The differences between the crude and the age-standardized prevalences appear to be minor. MetS was found in 41.7% of women and in 26.8% of men (34.7% for both sexes). In all age groups, prevalences were found to be higher among women than among men. While MetS was shown to decrease with age among men (by 1.2% (0.4%–4.5%) per additional year of age, p<0.05), this was not found to be the case among women.

Table 2.

Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and its components by sex and age group

| Age/gender group | n | MetS, % | Abdominal obesity, % | Hypertension, % | Elevated TG, % | Depressed HDL C, % | Hyperglycemia, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | |||||||

| Ages: 55–59 | 146 | 43.8 | 64.4 | 52.1 | 25.3 | 44.5 | 31.5 |

| 60–69 | 428 | 40.4 | 51.9 | 60.5 | 25.0 | 45.3 | 29.4 |

| 70–79 | 304 | 41.1 | 54.3 | 72.0 | 21.1 | 46.4 | 22.4 |

| 80+ | 77 | 46.8 | 57.1 | 79.2 | 22.1 | 58.4 | 23.4 |

|

| |||||||

| Ages 55+ | 955 | 41.7 | 55.0 | 64.4 | 23.6 | 46.6 | 27.0 |

| Ages 55+, age-standardized# | 955 | 42.3 | 56.4 | 61.6 | 24.1 | 47.4 | 28.1 |

|

| |||||||

| Men | |||||||

| Ages: 55–59 | 127 | 30.7 | 29.9 | 68.5 | 29.9 | 24.4 | 37.0 |

| 60–69 | 319 | 29.5 | 29.2 | 69.9 | 24.8 | 27.0 | 38.9 |

| 70–79 | 288 | 24.7 | 29.5 | 75.0 | 18.4 | 24.0 | 34.7 |

| 80+ | 99 | 19.2 | 26.3 | 67.7 | 13.1 | 23.2 | 22.2 |

|

| |||||||

| Ages 55+ | 833 | 26.8 | 29.1 | 71.2 | 22.0 | 25.1 | 35.2 |

| Ages 55+, age-standardized | 833 | 28.3 | 29.3 | 70.0 | 24.5 | 25.4 | 36.0 |

Segi’s world population standard

Of the MetS components, hypertension was found to be the most prevalent, affecting 64.3% (95%CI 62.9–65.8) of the women and 71.2% (95%CI 69.9–72.6) of the men. Other components frequently observed among women included abdominal obesity, which was confirmed in 55.0% (95%CI 53.4–56.5) of the female sample, and low HDL C, which was reported for 46.6% (95%CI 45.0–48.2) of the women. Among the men, the second-most common component was found to be an elevated fasting glucose level, affecting 35.2% (95%CI 33.6–36.7) of the male sample. Elevated TG was shown to be much less prevalent than the other components for both sexes, affecting 23.5% (95%CI 22.3–24.6) of the women and 22.1% (95%CI 20.9–23.2) of the men.

When the individual components of MetS are compared, the most pronounced female-male gaps can be seen in abdominal obesity and in lowered HDL C (Table 2). In order to find out which of the five MetS components explain the higher level of metabolic abnormalities in women, MetS was regressed on sex with and without controlling for each of the five individual MetS components. The results demonstrate the importance of abdominal obesity and HDL C (Table 3). The strong age-adjusted effect of being female (OR=1.961, 95%CI 1.602–2.401, p<0.001) totally disappeared after we adjusted for abdominal obesity (OR=1.058, 0.825–1.358, p=0.654), and became weaker after we adjusted for HDL C (OR=1.283, 95%CI 1.009–1.612, p<0.05).

Table 3.

Effects of female sex on metabolic syndrome before and after adjustment for individual metabolic components#

| Explanatory variables | OR | 95%CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.961 | 1.602 | 2.401 | <0.0001 |

| Age + Abdominal obesity | 1.058 | 0.825 | 1.358 | NS& |

| Age + Hypertension | 2.403 | 1.934 | 2.986 | <0.0001 |

| Age + Elevated TG | 2.505 | 1.957 | 3.205 | <0.0001 |

| Age + Low HDL C | 1.275 | 1.009 | 1.612 | 0.0417 |

| Age + Hyperglycemia | 3.114 | 2.440 | 3.973 | <0.0001 |

Odd ratios for variable sex in six logistic regressions with different sets of variables under control.

Not significant.

Having a higher level of education was found to be associated with lower ORs of having MetS among women (OR=0.708, 95%CI 0.544–0.921, p<0.01), but not among men. Lower education was also shown to be associated with abdominal obesity among women, and with hypertension and decreased HDL C among women and men (data not shown. In spite of these associations, the prevalence of MetS in the sample increased very little after the elimination (by means of standardization) of the educational difference between the sample and the general population of Moscow (35.6% vs. 34.7%), and also between the sample and the general population of Russia (36.6% vs. 34.7%).

3.3. Metabolic syndrome and biochemical markers

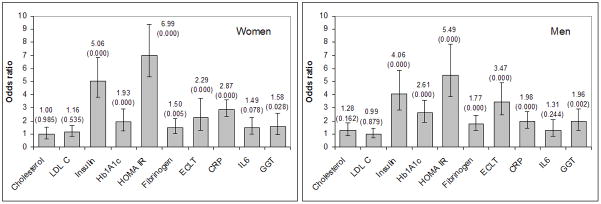

Figure 1 shows the odds ratios for the associations between MetS and markers of lipid profile, insulin-resistance, prothrombotic status, and low-grade inflammation. MetS was found to be strongly associated with fasting hyperinsulinemia: OR=5.058 (3.681–6.950) for women and 4.058 (2.815–5.850) for men, with insulin resistance (elevated HOMA-IR): OR=6.994 (95%CI 5.030–9.727) for women and 5.494 (3.843–7.853) for men and with HbA1c: OR=1.928 (95%CI 1.478–2.514) for women and 2.607 (95%CI 1.896–3.585) for men (all p<0.001).

Figure 1. Links between metabolic syndrome and selected biomedical variables: age-adjusted odds ratios with 95% CI.

Note: p-values are given in parentheses. Cutpoints for the explanatory variables: Cholesterol>5 mmol/L; LDLC>3 mmol/L; Insulin>13 μU/mL; Hb1A1c>6.0%; HOMA IR>3.5; Fibrinogen>4 g/L; ECLT>240 min; hsCRP>3 mg/L; IL6>4 pg/L; GGT>49.0 U/L.

MetS was shown to be associated with markers of haemostatic abnormality such as elevated fibrinogen: OR=1.502 (1.148–1.968) for women and 1.775 (1.297–2.429) for men, and with decreased fibrinolysis (elevated ECLT): OR=2.288 (95%CI 1.703–3.075) for women and 3.474 (95%CI 2.458–4.909) for men (all p<0.0001).

Among the inflammation markers, MetS was found to be associated with increased hsCRP: OR=2.863 (2.158–3.798) for women and 1.975 (1.426–2.736) for men (all p<0.001), as well as with elevated GGT activity: OR=1.581 (1.035–2.416, p<0.01) for women and 1.962 (1.310–2.939, p<0.001) for men. In women, a weak association was also observed between MetS and IL-6: OR=1.489 (0.948–2.339).

4. Discussion

The main objective of this study was to assess the prevalence of MetS in a population-based sample of 1,788 Muscovites. We also examined links between MetS on the one hand; and age, sex, education, markers of insulin-resistance, prothrombotic status, and low-grade inflammation on the other. To our knowledge, this is the first study that has examined the prevalence and features of MetS in population-based sample of elderly Russians aged 55 and older (68.4 years on average) who are exposed to high cardiovascular and all-cause mortality hazards.

Our analysis showed that MetS prevalence was 41.7% (n=955) for women and 26.8% (n=833) for men. The corresponding age-standardized (Segi’s world population standard) prevalence figures were 42.3% and 28.3%. For older women, the prevalence of MetS found in the Russian sample is comparable to levels observed in industrialized countries with the highest rates of MetS; for older men, the prevalence of MetS was shown to be roughly the same as the levels observed in industrialized countries with average or slightly higher-than-average levels of MetS (Balkau et al., 2002; Ford et al., 2002; Cameron et al., 2004; Dupuy et al., 2007; Hildrum et al., 2007).

Our overall prevalence estimates are much higher than the figures reported in the Arkhangelsk study, which was focused on a much younger group (Sidorenkov et al., 2010). However, for ages 60 and older the Arkhangelsk results are comparable to the results of our study: 44.8% (n=297) for women and 24.4% (312) for men versus 41.3% (809) and 26.1% (706), respectively. For people in their 50s, the MetS prevalence in Arkhangelsk is substantially lower than that in our study: 17.7% (290) for women and 15.5% (298) for men aged 50 to 59 versus 43.8% (146) for women and 30.7% (127) for men aged 55 to 59, respectively. Although it is possible that this discrepancy is partly attributable to regional differences between Arkhangelsk and Moscow, possible selectivity of the Arkhangelsk sample acknowledged by the authors (Sidorenkov et al., 2010, p. 4) may have also played a role.

It is well established that the prevalence of MetS rises from young to old ages (Ford et al., 2002; Cameron et al., 2004; Hildrum et al., 2007). Studies with good coverage of the elderly have also suggested that the increase slows down and even reverses after ages 60 to 65 (Ford et al., 2002; Gu et al., 2002; Kuzuya et al., 2007). In earlier works, the decrease in MetS among the oldest individuals was found to be more pronounced for men than for women (Kuzuya et al., 2007). Our results are completely consistent with these observations. In the Moscow sample, MetS prevalence reached a peak at ages 60 to 69, and then significantly decreased for men, but not for women.

The results of our study showed that elderly women in Moscow were 1.5 times more likely than Muscovite men to suffer from MetS. This finding is similar to the gender ratio reported for the younger age sample in Arkhangelsk (Sidorenkov et al., 2010). Yet in most Western countries, the prevalence of MetS has either not been shown to differ substantially by gender, or the prevalence has been found to be slightly higher in men than in women (Isomaa et al., 2001; Balkau et al., 2002; Ford et al., 2002; Cameron et al., 2004). At the same time, however, a substantially higher prevalence of MetS in women than in men was observed in several countries in Asia and Eastern Europe, as well as among African, Hispanic, and Native Americans (Ford et al., 2002; Cameron et al., 2004; Cankurtaran et al., 2006; Mokan et al., 2008).

Our analysis showed that the main factors that explain why MetS prevalence was significantly higher in elderly Muscovite women than men were the higher levels of obesity and the lower levels of HDL C among women. Abdominal obesity was found in more than half of the women, and in less than one-third of the men. Abdominal obesity is an important contributor to the development of insulin resistance, and is a widely accepted underlying factor of MetS pathogenesis. Furthermore, fat tissue secretes several pro-inflammatory cytokines, or adipokines. With abdominal fat accumulation, the production and secretion of certain adipokines is increased, inducing inflammation and predisposing patients to the development of metabolic abnormalities (Grundy et al., 2005).

Higher prevalence of low antiatherogenic HDL C in women than in men (47% vs. 25%) is the second major contributor to higher rates of female MetS.

Of the environmental and behavioral factors that might influence the female-male MetS gap, maternity and gender differences in alcohol use may be the most important. With regard to maternity, prospective studies have shown that childbearing was associated with elevated risks of long-term abdominal adiposity and decreased HDL C level, compared to the period before pregnancy (Gunderson et al., 2004; Loucks et al., 2007).

With regard to alcohol, the Russian male-female gap in alcohol intake is known to be unusually large (Deev et al., 1997; Carlson and Vågerö, 1998; Bobak et al., 1999). While an underreporting of alcohol intake is possible (Mustonen, 1997; Stockwell et al., 2004), the results of our study clearly indicate that, even at advanced ages, many Russian men continue to drink substantial amounts of alcohol, while women of the same age drink very little. These facts, together with evidence that alcohol has a positive effect upon blood lipid profile (Klatsky, 2009), suggest that the relatively high HDL C levels and the moderate levels of total cholesterol found in Russian men can be (at least partly) related to alcohol consumption (Shestov et al., 1993).

We also found differences between the genders with respect to the inverse relationship between MetS and education, which was evident in women but not in men. This finding is in line with prior research, which showed a similar sex-specificity of socioeconomic disparities in MetS in France and the USA (Dallongeville et al., 2005; Loucks et al., 2006). Following the logic of the male-female metabolic gap, this dissimilarity can be at least partly attributed to the higher number of births among women with lower levels of education (Zakharov, 2008), and the higher alcohol intake among men with lower levels of education (Malyutina et al., 2004). While the former factor can reinforce the socioeconomic differential in MetS among women, the latter factor can ameliorate the socioeconomic differential among men.

Compared to other populations, Muscovites were found to be characterized by a specific distribution of individual metabolic components. According to our data, arterial hypertension was the most common MetS component both in women and men. It was followed by abdominal obesity in women and by an elevated fasting glucose level in men. HDL C level depression was another highly prevalent MetS component among Muscovite women.

Quite similar results have been reported for elderly Swedes (Gause-Nilsson et al, 2008) and Italians (Maggi et al., 2008). Both of these studies showed a high prevalence of hypertension among men and women and of obesity among women. In the Swedish study (as in the Moscow study), elevated fasting glucose was found to be the second most prevalent MetS component among men. In the Italian study, however, and elevated TG level was identified as the second-most prevalent component of MetS for men. Hypertension and central obesity were also found to be leading components of MetS among Turkish people aged 65 and older (Cankurtaran et al., 2006), but the prevalence of adiposity in this study was almost half that of the Moscow study.

On the other hand, the Framingham Offspring Study (FOS) and the San Antonio Heart Study (SAHS) found that lowered HDL C and hypertension were the two most prevalent single metabolic components in both women and men (Meigs et al., 2003). These results diverge from the findings of the Moscow study.

Our study identified associations between MetS or its components and other disorders, including insulin resistance, hypercoagulability and hypofibrinolysis and elevated markers of chronic inflammation. The strong relationships found between the syndrome and the direct characteristics of glucose metabolism and insulin resistance were expected (since fasting glucose is a component of MetS) and confirm the prognostic importance and clinical significance of MetS. These results are in line with those of other studies (Wannamethee et al., 2005; Jellinger, 2007; Kanbak et al., 2010). Our findings regarding the relationship between MetS and pro-inflammatory markers and markers of decreased fibrinolysis are also consistent with international evidence. Corresponding links between MetS or its individual components and hsCRP levels (Lao et al., 2007; Zuliani et al., 2009) and disorders in the fibrinolytic system and elevated coagulation have been detected in several elderly populations (Nieuwdorp et al., 2005; Alessi and Juhan-Vague, 2006; Palomo et al., 2006).

An interesting finding of this study is a relationship between MetS and elevated serum GGT activity. A similar relationship was detected in Arkhangelsk (Sidorenkov, Nilssen, Grjibovski, 2010). In other studies, increased GGT activity was found to be associated with arterial hypertension and Type 2 diabetes; with all-cause and CVD mortality, independent of alcohol intake or liver disease (Onat et al., 2002); and with an elevated risk of new-onset MetS; even after adjustments were made for age, sex, BMI, BP, fasting glucose, smoking status, and alcohol consumption (Lee et al., 2011). A modest elevation in serum GGT activity is regarded as an early marker of cellular oxidative stress, or, like other hepatic enzymes, as a marker reflecting the presence of inflammation, which can impair insulin signaling, both in the liver and systemically. However, the precise mechanisms through which liver enzymes increase the likelihood of MetS and diabetes mellitus development have yet to be fully explained.

5. Conclusion

Data on the population prevalence of metabolic syndrome and its individual components can provide useful information about the potential burden of metabolic and cardiovascular disorders, and thus facilitate health care planning. It appears that MetS is highly prevalent among elderly Muscovite women, and is quite common among Muscovite men. Hypertension and abdominal obesity in women and hypertension and hyperglycemia in men are the most frequent components of MetS. The metabolic burden is an important contributor to the high levels of ill health in elderly Russians and especially in Russian women. However, in a sample of younger men and women from Arkhangelsk, MetS was found to be unrelated to all-cause mortality, mortality from all cardiovascular and from ischemic heart diseases (Sidorenkov, Nilssen, Grjibovski, 2010).

This result and other considerations suggest that these metabolic changes cannot explain the substantially higher rates of cardiovascular mortality among Russians than among the populations of other industrialized countries. While the prevalence of MetS is lower among Russian men than among their US counterparts, mortality from CVD is about three times higher among Russian men. To help explain this discrepancy, future studies should pay special attention to the mechanisms of heart failure, arrhythmia, cardiomyopathia, and hemorrhage stroke, especially in connection with the high levels of alcohol and tobacco use among Russian men (Leon et al., 2010). The quality of diagnostics and the coding of IHD as a cause of death in Russia deserves further investigation as well (Zaridze et al., 2009).

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by research grant R 01 AG 026786 from the National Institute of Aging (USA). The funding agency had no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; in writing the manuscript; or in the decision to submit it for publication. We are grateful to Edelgard Katke for careful check and formatting the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alessi M-C, Juhan-Vague I. PAI-1 and the metabolic syndrome. Links, causes, and consequences. Arterioscler Throm Vas. 2006;26:2200–2207. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000242905.41404.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreev EM, McKee M, Shkolnikov VM. Health expectancy in the Russian Federation: a new perspective on the health divide in Europe. B World Health Organ. 2003;81(11):778–788. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balkau B, Charles MA, Drivsholm T, Borsch-Johnsen K. Frequency of the WHO metabolic syndrome in European cohorts, and an alternative definition of insulin resistance syndrome. Diabetes Metab. 2002;28:364–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobak M, McKee M, Rose R, Marmot M. Alcohol consumption in a national sample of the Russian population. Addiction. 1999;94:857–866. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.9468579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron AJ, Shaw JF, Zimmet PZ. The metabolic syndrome: prevalence in worldwide populations. Endocrinol Metab Clin N Am. 2004;33:351–375. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cankurtaran M, Halil M, Yavuz BB, Dagli N, Oyan B, Ariogul S. Prevalence and correlates of metabolic syndrome in older adults. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2006;42:35–45. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson P, Vågerö D. The social pattern of heavy drinking in Russia during transition. Evidence from Taganrog 1993. Eur J Public Health. 1998;8:280–289. [Google Scholar]

- Deev A, Shestov D, Abernathy J, Kapustina A, Muhina N, Irving S. Association of alcohol consumption to mortality in middle aged U.S. and Russian men and women. Ann Epidemiol. 1997;8:147–153. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(98)00004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallongeville J, Cottel D, Ferrières J, Arveiler D, Bingham A, Ruidavets JB, Haas B, Ducimetiere P, Amouyel P. Household income is associated with the risk of metabolic syndrome in a sex-specific manner. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:409–415. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.2.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupuy AM, Jaussent I, Lacroux A, Durant R, Cristol JP, Delcourt C POLA Study Group. Waist circumference adds to the variance in plasma C-reactive protein levels in elderly patients with metabolic syndrome. Gerontology. 2007;53:329–339. doi: 10.1159/000103555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmer PZ. The metabolic syndrome. Lancet. 2005;365:1415–1428. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66378-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Executive summary of the Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, And Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) J Amer Med Assoc. 2001;285:2486–2497. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford ES, Giles WH, Dietz WH. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among US adults: findings from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Amer Med Assoc. 2002;287:356–359. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.3.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galassi A, Reynolds K, He J. Metabolic syndrome and risk of cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2006;119:812–819. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gami AS, Witt BJ, Howard DE, Erwin PJ, Gami LA, Somers VK, Montori VK. Metabolic syndrome and risk of incident cardiovascular events and death. A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:403–414. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gause-Nilsson I, Gherman S, Kumar Dey D, Kennerfalk A, Stehen B. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in an elderly Swedish population. Acta Diabetol. 2006;43:120–126. doi: 10.1007/s00592-006-0226-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson EP, Murtaugh MA, Lewis CE, Quesenberry CP, West DS, Sidney S. Excess gains in weight and waist circumference associated with childbearing: The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study (CARDIA) Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28:525–535. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson EP, Lewis CE, Murtaugh MA, Quesenberry CP, Smith West D, Sidney S. Long-term plasma lipid changes associated with a first birth: The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:1028–1039. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, Donato KA, Eckel RH, Franklin BA, Gordon DJ, Krauss RM, Savage PJ, Smith SC, Spertus JA, Costa F. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: An AHA/NHLBI Scientific Statement. Circulation. 2005;112:2735–2752. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.169404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haffner SM, Valdez RA, Hazuda HP, Mitchell BD, Morales PA, Stern MP. Prospective analysis of the insulin-resistance syndrome (syndrome X) Diabetes. 1992;41:715–722. doi: 10.2337/diab.41.6.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y, Jiang B, Wang J, Feng K, Chang Q, Fan L, Li X, Hu FB. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome and its relation to cardiovascular disease in an elderly Chinese population. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:1588–1594. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.11.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Online Database. World Health Organisation. Office for Europe; Health for All. Available at http://data.euro.who.int/hfadb/ last visited 6.05.2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hildrum B, Mykletun A, Hole T, Midthjell K, Dahl AA. Age-specific prevalence of the metabolic syndrome defined by the International Diabetes Federation and the National Cholesterol Education Program: the Norwegian HUNT 2 study. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:220–228. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jellinger PS. Metabolic consequences of hyperglycemia and insulin resistance. Excerpta Medica. 2007;4 (1):2–14. doi: 10.1016/s1098-3597(07)80019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu D, Reynolds K, Wu X, Chen J, Duan X, Reynolds RF, Whelton PK, He J for the InterASIA Collaborative Group. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and overweight among adults in China. Lancet. 2005;365:1398–1405. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66375-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isomaa B, Almgren P, Tuomi T, Forsen B, Lahti K, Nissen M, Taskinen MR, Groop L. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality associated with the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:683–689. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.4.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanbak G, Akalin A, Dokumacioglu A, Ozcelik E, Bal C. Cardiovascular risk assessment in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and metabolic syndrome: role of biomarkers. Diab Met Syndr: Clin Res Rev. 2011;5:7–11. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klatsky AL. Alcohol and cardiovascular health. Physiol Behav. 2009;100:76–81. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2009.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuzuya M, Ando F, Iguchi A, Shimokata H. Age-specific change in prevalence of metabolic syndrome: Longitudinal observation of large Japanese cohort. Atherosclerosis. 2007;191:305–312. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lao XQ, Thomas GN, Jiang CQ, Zhang WS, Yin P, Adab P, Lam TH, Cheng KK. c-Reactive protein and the metabolic syndrome in older Chinese: Guangzhou biobank cohort study. Atherosclerosis. 2009;194:483–489. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.08.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DS, Evans JC, Robins SJ, Wilson PW, Albano I, Fox CS, Wang TJ, Benjamin EJ, D’Agostino RB, Vasan RS. Gamma glutamyl transferase and metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, and mortality risk: The Framingham Heart Study. Arterioscl Throm Vas. 2007;27:127–133. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000251993.20372.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon DA, Shkolnikov VM, McKee M, Kiryanov N, Andreev E. Alcohol increases circulatory disease mortality in Russia: acute and chronic effects or misattribution of cause? Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39:1279–1290. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loucks EB, Rehkopf DH, Thurston RC, Kawachi I. Socioeconomic disparities in metabolic syndrome differ by gender: evidence from NHANES III. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2006.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggi S, Noale M, Zambon A, Limongi F, Romanato G, Crepaldi G for the ILSA Working Group. Validity of the ATP III diagnostic criteria for the metabolic syndrome in an elderly Italian Caucasian population. The Italian Longitudinal Study on Aging. Atherosclerosis. 2008;197:877–882. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malyutina S, Bobak M, Kurilovich S, Nikitin Y, Marmot M. Trends in alcohol intake by education and marital status in an urban population in Russia between the mid 1980s and the mid 1990s. Alcohol Alcoholism. 2004;39:64–69. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agh022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthew DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. 1985;28:412–419. doi: 10.1007/BF00280883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meigs JB, Wilson PWF, Nathan DM, D’Agostino RB, Williams K, Haffner SM. Prevalence and characteristics of the metabolic syndrome in the San Antonio Heart and Framingham Offsprings Studies. Diabetes. 2003;52:2160–2167. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.8.2160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meslé F. Mortality in Central and Eastern Europe: long-term trends and recent upturns. Demogr Res Special Collection 2 Article. 2004;3:45–50. [Google Scholar]

- Mokáň M, Galajda P, Prídavková D, Tomášková V, Šutarík L, Kručinská L, Bukovská’ A, Rusnáková G. Prevalence of diabetes mellitus and metabolic syndrome in Slovakia. Diabetes Res Clin Pr. 2008;81:238–242. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustonen H. Positive and negative experiences related to drinking. In: Simpura J, Levin B, editors. Demystifying Russian Drinking Comparative Studies from the 1990s. Research Rep85, Gummerus Kirjapaino Oy; Helsinki: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwdorp M, Stroes ESG, Meijers JCM, Büller H. Hypercoagulability in the metabolic syndrome. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2005;5:155–159. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onat A, Ceyhan K, Basar O, Erer B, Toprak S, Sansoy V. Metabolic syndrome: major impact on coronary risk in a population with low cholesterol levels: a prospective and cross-sectional evaluation. Atherosclerosis. 2002;165:285–292. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(02)00236-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palomo I, Alarson M, Moore-Carrasco R, Argiles JM. Hemostasis alterations in metabolic syndrome (Review) Intern J Mol Med. 2006;18:969–974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shestov DB, Deev AD, Klimov AN, Davis CE, Tyroler HA. Increased risk of coronary heart disease death in men with low total and low-density Lipoprotein Cholesterol in the Russian lipid research clinics prevalence follow-up study. Circulation. 1993;88:846–853. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.3.846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shkolnikova M, Shalnova S, Shkolnikov VM, Metelskaya V, Deev A, Andreev E, Jdanov D, Vaupel JW. Biological mechanisms of disease and death in Moscow: rationale and design of the survey on Stress Aging and Health in Russia (SAHR) BMC Public Health. 2009;9:293. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-293. http://www.biomedcentral.com/content/pdf/1471-2458-9-293.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidorenkov O, Nilssen O, Brenn T, Martushov S, Arkhipovsky VL, Grjibovski AM. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome and its components in Northwest Russia: the Arkhangelsk study. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:23. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-23. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/10/23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidorenkov O, Nilssen O, Grjibovski AM. Metabolic syndrome in Russian adults: associated factors and mortality from cardiovascular diseases and all causes. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:582. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-582. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/10/582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockwell T, Donath S, Cooper-Stanbury M, Chikritzhs T, Catalano P, Mateo C. Under-reporting of alcohol consumption in household surveys: a comparison of quantity-frequency, graduated-frequency and recent recall. Addiction. 2004;99:1024–1033. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Demographic Yearbook of Russia. Federal Service for Federal Statistics. Moscow: Statistical Handbook 2010; p. 525. [Google Scholar]

- The IDF consensus worldwide definition of the metabolic syndrome. International Diabetes Federation; Brussels: 2006. Available at http://www.idf.org/webdata/docs/IDF_Meta_def_final.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Tzou WS, Douglas PS, Srinivasan SR, Bond MG, Tang R, Chen W, Berenson GS, Stein JH. Increased subclinical atherosclerosis in young adults with metabolic syndrome. The Bogalusa Heart Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:457–463. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.04.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vserossiyskaya Perepis’ naseleniya 2002 goda [All Russia Population Census of 2002] Available at http://www.perepis2002.ru/index.html?id=12.

- Vallin J, Andreev E, Meslé F, Shkolnikov VM. Geographical diversity of cause-of-death patterns and trends in Russia. Demographic Research. 2005;12(13):323–380. Available at http://www.demographic-research.org/Volumes/Vol12/13/12-13.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Wannamethee SG, Lowe GDO, Shaper AG, Rumley A, Lennon L, Whincup PH. The metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance: relationship to haemostatic and inflammatory markers in older non-diabetic men. Atherosclerosis. 2005;191:101–108. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakharov S. Russian Federation: from the first to the second demographic transition. Demographic Research. 2008;24:908–951. available at http://www.demographic-research.org/Volumes/Vol19/24/19-24.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Zaridze D, Maximovitch D, Lazarev A, Igitov V, Boroda A, Boreham J, Boyle P, Peto R, Boffetta P. Alcohol poisoning is a main determinant of recent mortality trends in Russia: evidence from a detailed analysis of mortality statistics and autopsies. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38:143–153. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuliani G, Volpato S, Galvani M, Ble A, Bandinelli S, Corsi AM, Lauterani F, Maggio M, Guralnik JM, Fellin R, Ferucci L. Elevated C-reactive protein levels and metabolic syndrome in the elderly: The role of central obesity. Data from the InChiati study. Atherosclerosis. 2009;203:626–632. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.07.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]