Abstract

Although use of buprenorphine in the treatment of opioid dependence is expected to continue to increase, little is known about the optimal setting for providing the medical and psychosocial care required with buprenorphine pharmacotherapy.

OBJECTIVE

This study compared buprenorphine therapy delivered in three distinct treatment settings: an opioid-treatment program (OTP) offering individual counseling; a group counseling program utilizing the manualized Matrix Model (MMM) of cognitive-behavioral treatment; and a private clinic setting mirroring standard medical management for buprenorphine treatment provided specifically at a psychiatrist’s private practice (PCS).

METHOD

Participants were inducted on buprenorphine and provided with treatment over a 52-week study duration. All participants were scheduled for weekly treatment visits for the first 6 study weeks, and two sites reduced treatment to monthly visits for dispensing of medication and psychosocial counseling. Outcomes include opioid use, participant retention in treatment, and treatment participation.

RESULTS

Participants presenting for treatment at the sites differed only by race/ethnicity, and opioid use did not differ by site. Retention differed by treatment site, with the number of participants who stayed in the study until the end of 20 weeks significantly associated with treatment site. The mean number of minutes spent in each individual counseling session also differed by site. Although no difference in opioid use by treatment site was found, results document a significant association between opioid use and buprenorphine dose.

DISCUSSION

These results show some differences by treatment site, although the similarity and relative ease in which the sites were able to recruit participants for treatment with buprenorphine, and minor implementation problems reported suggests the feasibility of treatment with buprenorphine across various treatment settings.

CONCLUSION

Similar rates of continued opioid use across study sites and few qualitative reports of problems indicates that treatment with buprenorphine and associated psychosocial counseling are safe and relatively easy to implement in a variety of treatment settings.

Keywords: buprenorphine, opioid treatment program, physicians

Introduction

Opioid dependence is a medical condition associated with severe and costly health and social consequences (Hser et al., 2001). Estimates from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) indicate a rapidly increasing population of people dependent on prescription opioids as well as heroin (SAMHSA, 2003). Methadone maintenance has been the predominant treatment for opioid dependence. Methadone treatment programs are subject to rigorous federal, state, and local regulations, and clinics tend to be located in large urban areas. In 2002, after more than a decade of efficacy research (Ling et al., 1997) the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved buprenorphine and a combination product containing buprenorphine and naloxone (Subutex® and Suboxone®) for maintenance or detoxification of opioid-dependent individuals (FDA, 2002). Buprenorphine is a partial opioid agonist that suppresses withdrawal and blocks the effects of additional opioids.

Legislation outlined in the Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000 (Ling et al., 1997; FDA, 2002) allowed qualified physicians to treat opioid dependence in the primary care office setting for the first time in 80 years. This legislation stipulates that physicians receive training about buprenorphine treatment of opioid-dependent patients and requires that physicians have the capacity to refer patients to psychosocial therapy (e.g., group counseling and individual counseling). In addition to pharmacological treatment with buprenorphine or methadone, behavioral therapy is necessary to address the psychological processes that underlie addiction. Behavioral interventions can include physician counseling, education, and monitoring. Alternatively, group therapy can teach cognitive behavioral strategies to avoid drug use and how to manage high-risk situations (Kakko et al., 2003).

The addition of buprenorphine to the arsenal of treatment alternatives for opioid dependence requires investigations to determine best practices for the delivery of buprenorphine and the psychosocial treatment component required. Elements of the treatment milieu that may impact outcomes include modality, the characteristics of the treatment provided, and the treatment providers. The current study was conducted to compare treatment outcomes of opioid-dependent individuals in three treatment settings with contrasting outpatient strategies, and to gather unstructured qualitative data from treatment providers to assess the feasibility of implementing buprenorphine treatment in each setting. Settings include: (1) a typical OTP is a structured clinical setting where the administration of methadone is observed, (2) a physician's primary care office, and (3) a cognitive behavioral group therapy program, which had not offered physician services on-site in the past.

Method

Participants

Potential participants were recruited beginning in September 1999 until December 2000 through flyers, web-based postings, newspaper ads, and word-of-mouth, and contacted study staff on a toll-free central recruiting number. Additional effort was made to enroll female participants through recruitment at local treatment sites where women were referred.

Candidates completed the informed consent procedure, and were screened to confirm meeting safety and eligibility criteria. The screening assessment included a comprehensive medical and psychiatric history, a physical examination, and laboratory tests. Eligibility requirements included: being opioid dependent based on DSM-III-R criteria (the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Revised Third Edition) 1, no medical or psychiatric condition that would interfere with treatment; no dependence on non-opioid prescription medications such as benzodiazepines or dependence on other drugs of abuse except tobacco; no methadone use in the last 30 days, or concurrent enrollment in a methadone program; and women of reproductive age were required to practice birth control and were excluded if they were pregnant or breastfeeding. The Institutional Review Board at the Friends Research Institute approved this research study.

Randomization

If deemed eligible, participants were randomized and scheduled to for induction onto buprenorphine. The randomization assignments were generated by computer software using block sizes. Assignments were printed on individual cards and kept in sealed envelopes until selected.

Participants were equally likely to be randomized to one of three different settings: (1) An Opioid Treatment Program (OTP), which included individual, one-on-one counseling sessions that emphasized practical aspects of recovery and coping with environmental stressors that may elicit craving and induce relapse to drug use; (2) A primary care setting (PCS), in which a physician provided supportive and educational counseling about drug abuse and recovery; (3) A behaviorally-oriented psychosocial treatment (MMM) using the manualized Matrix Recovery-Relapse Prevention Model (McCann et al., 2005). All participants received Suboxone®, a sublingual formulation of buprenorphine and naloxone.

Assessments

In addition to baseline assessments collected during the screening process, participants were assessed twice during the week of medication induction, once weekly through week 9, and monthly during weeks 10 through 52. The study team documented opioid withdrawal symptoms and adverse events. Urine samples were analyzed on site for amphetamine, benzoylecgonine (cocaine metabolite), barbiturates, opioids, and benzodiazepines using test cups (Roche Diagnostic Corporation, OnTrak Testcup-5) (Bogema, 2006). The Addiction Severity Index (ASI) (Cacciola et al., 1997) was administered on the first and last visit. In keeping with the naturalistic nature of the study, participants were given a choice of detoxification or maintenance; medically stable participants who requested detoxification were offered a buprenorphine taper to begin after six weeks. Participants could alternatively select buprenorphine maintenance for 52 weeks, buprenorphine taper scheduled for the end of the 52-week study. Participants were also given referrals to other treatment resources at discharge. Efforts were made to contact study participants for follow-up assessments at intervals of 30, 90, and 180 days. Those who completed the follow-up assessment were given $25 in compensation.

Treatment

Participants were provided with Suboxone 2mg tablets (2mg buprenorphine and 0.5mg naloxone) and/or 8mg tablets (8mg buprenorphine and 2mg naloxone). Suboxone is expressed in terms of buprenorphine for this paper (e.g., 8mg, 2mg). Study medication was dispensed at a single pharmacy located several miles from the treatment settings.

Participants were instructed to present at clinic at least 12 hours after their last opioid use for medication induction. The study physician selected an initial dose of 2, 4, or 8mg of buprenorphine at his/her discretion, with a subsequent dose of 8mg later in the day. Initial dose was based on the severity of withdrawal symptoms and physician assessment. Physician discretion was the standard for dose determination at each of the three sites, in accordance with the naturalistic nature of the study. After the first induction day, the study physician could adjust the dose up to a maximum of 24mg per day. As part of diversion monitoring, participants were subject to random callbacks on a quarterly basis to verify the amount of medication they had on hand.

In conjunction with study drug, each participant was randomly assigned to treatment site. Each treatment site offered distinct psychosocial intervention: (1) The OTP provided opioid supportive counseling by a certified drug and alcohol counselor at the time of the medication visit (once weekly during weeks 1–6, once monthly during weeks 7–52). Individual appointment times were restricted to the hours between 6 and 10 a.m. (2) A physician provided brief counseling in the primary care setting (PCS). Flexible appointment times were available during the day and were offered once weekly during weeks 1–6, and once monthly during weeks 7–52. (3) The behaviorally-oriented psychosocial treatment (MMM) included weekly cognitive behavioral groups conducted by a master’s level clinician for the duration of the subjects’ participation. Participants were encouraged to attend the weekly counseling groups but these were not mandatory. Participants could receive a buprenorphine prescription by seeing the on-site study physician without attending group sessions. The MMM group therapy and physician visits were held in the evening.

Outcome Measures and Statistical Analyses

Outcome efficacy measures included opioid use, treatment retention, and treatment participation. An objective measure of drug use utilized results from urine toxicology tests. The Treatment Effectiveness Score (TES) (Ling et al., 1998) was used to calculate the proportion of negative urine tests over all tests possible.

Treatment retention was measured as both a continuous variable, and a dichotomous variable. As a continuous variable, retention was measured as the number of weeks between induction and the last day the participant was assessed during the treatment period and was tested using Kaplan-Meier survival curves and a Wilcoxen rank sum test to compare the groups across sites. Retention was also measured by percentage of the group who were present at Week 9, and at Week 20. Treatment participation was measured by number and minutes of sessions attended and types of counseling received.

Eleven couples volunteered for the study, and 10 women and their male partners were randomized. To avoid likely problems associated with randomization to different sites, the female partners were randomized and their male counterparts were yoked to the same treatment condition. To simplify analyses, rather than adjusting analyses for the yoked assignments, the data collected from the male partners was excluded from the between-group comparisons.

Unstructured qualitative data was collected from the study physician and staff at each study site as possible, in order to document site experiences in the use of buprenorphine for opioid dependence. Because of the unstructured nature of this information, some practical information provided by the sites is presented in the results section, however, additional information on site experiences is included in the discussion section

Results

Participant Characteristics

Of the 124 individuals screened, 20 participants either failed to meet study eligibility or failed to show up for randomization, and 10 male partners were eliminated from analyses, leaving a total of 94 study participants included in these analyses. The number of randomized participants included 28 in OTP, 33 in PCS, and 33 in MMM.

The final sample included more men (58%) than women (42%), and most were white (58%) or Hispanic (28%). Table 1 shows baseline demographic characteristics and related variables by treatment site. At baseline, participants in the three settings had a significantly different distribution for race (chi-square = 12.83; p = 0.01), with 24% Black (non-Hispanic) participants in the PCS site, whereas only 7% and 6% of participants were Black (non-Hispanic) in the OTP and MMM sites respectively. Similarly, 50% of the participants self-reported as “other” race/ethnicity (American Indian, Alaskan Native, Asian or Hispanics) in the OTP site but only 18% and 24% belonged to that category in the PCS and MMM sites, respectively.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and associated variables by treatment site.

| Characteristics (N = 94) | Mean (Std. Dev.)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| OTP (n = 28) | PCS (n = 33) | MMM (n = 33) | |

| Age | 34.51 (10.47) | 36.46 (9.76) | 35.24 (9.88) |

|

| |||

| Education completed | |||

| Number of years | 12.50 (2.41) | 13.09 (1.83) | 13.33 (2.16) |

|

| |||

| Number of days with medical problems in the past 30 days | 1.32 (5.69) | 1.91 (5.86) | 1.76 (5.80) |

|

| |||

| Number of days with Psychological or Emotional problems in the past 30 days | 0.65 (1.94) | 4.00 (8.27) | 0.79 (2.33) |

|

| |||

|

% (n)

|

|||

| OTP | PCS | MMM | |

|

| |||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 67.86 (19) | 51.52 (17) | 57.58 (19) |

| Female | 32.14 (9) | 48.48 (16) | 42.42 (14) |

|

| |||

| Race* | |||

| White (not Hispanic) | 42.86 (12) | 57.58 (19) | 69.70 (23) |

| Black (not Hispanic) | 7.14 (2) | 24.24 (8) | 6.06 (2) |

| American Indian | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3.03 (1) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0 (0) | 3.03 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Hispanic-Mexican | 28.57 (8) | 6.06 (2) | 9.09 (3) |

| Hispanic Puerto Rican | 3.57 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Other Hispanic | 17.86 (5) | 9.09 (3) | 12.12 (4) |

|

| |||

| In controlled environment in the past 30 days | |||

| No | 100 (28) | 100 (33) | 96.97 (32) |

| Alcohol/Drug treatment | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3.03 (1) |

|

| |||

| Usual employment pattern (past 3 yrs) | 50.00 (14) | 42.42 (14) | 30.30 (10) |

| Full time | 17.86 (5) | 18.18 (6) | 18.18 (6) |

| Part time (reg. hrs.) | 10.71 (3) | 12.12 (4) | 18.18 (6) |

| Part time (irreg. day work) | 3.57 (1) | 6.06 (2) | 3.03 (1) |

| Student | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3.03 (1) |

| Retired/disability | 17.86 (5) | 21.21 (7) | 27.27 (9) |

| Unemployed | |||

|

| |||

| On probation or parole | |||

| Yes | 10.71 (3) | 12.12 (4) | 6.25 (2) |

| No | 89.29 (25) | 87.88 (29) | 93.75 (30) |

|

| |||

| Arrested for some crime in lifetime | |||

| Yes | 46.43 (13) | 63.64 (21) | 54.55 (18) |

| No | 53.57 (15) | 36.36 (12) | 45.45 (15) |

|

| |||

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 14.81 (4) | 6.25 (2) | 12.12 (4) |

| Widowed | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 6.06 (2) |

| Separated | 11.11 (3) | 9.38 (3) | 6.06 (2) |

| Divorced | 14.81 (4) | 25.00 (8) | 9.09 (3) |

| Never Married | 59.26 (16) | 59.38 (19) | 66.67 (22) |

|

| |||

| Was emotionally abused by family/ friends/neighbors in the past 30 days | |||

| Yes | 11.11 (3) | 18.75 (6) | 9.09 (3) |

| No | 88.89 (24) | 81.25 (26) | 90.91 (30) |

|

| |||

| Physically abused by family/friends/ neighbors in the past 30 days | |||

| Yes | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3.03 (1) |

| No | 100 (27) | 100 (32) | 96.97 (32) |

|

| |||

| Sexually abused by family/ friends/ neighbors in the past 30 days | |||

| Yes | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| No | 100(27) | 100 (32) | 100 (33) |

Significantly different among treatment conditions (p<0.05)

Table 2 shows baseline drug use characteristics. There were no significant baseline differences found among the participants groups across treatment sites.

Table 2.

Drug Use Characteristics.

| Drug | Mean (Std. Dev.)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| OTP (n = 28) | PCS (n = 33) | MMM (n = 33) | |

| Alcohol | |||

| Past 30 days | 6.43 (8.73) | 2.45 (5.57) | 4.12 (8.52) |

| Lifetime | 9.75 (8.59) | 9.18 (9.25) | 12.64 (10.71) |

|

| |||

| Alcohol Intoxication | |||

| Past 30 days | 1.64 (4.12) | 0.27 (0.84) | 0.24 (0.90) |

| Lifetime | 3.07 (4.09) | 3.06 (5.40) | 4.82 (6.89) |

|

| |||

| Heroin | |||

| Past 30 days | 28.32 (6.24) | 29.88 (0.69) | 27.52 (7.36) |

| Lifetime | 8.96 (10.02) | 10.00 (9.39) | 9.55 (11.09) |

|

| |||

| Methadone | |||

| Past 30 days | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Lifetime | 0.71 (1.21) | 0.97 (1.38) | 0.85 (2.12) |

|

| |||

| Other opioids/analgesics | |||

| Past 30 days | 1.71 (5.79) | 0.79 (2.03) | 2.21 (6.57) |

| Lifetime | 0.46 (1.89) | 0.94 (2.03) | 2.36 (5.59) |

|

| |||

| Barbiturates | |||

| Past 30 days | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.33 (0.96) |

| Lifetime | 0.29 (1.51) | 0.24 (0.79) | 1.85 (5.29) |

|

| |||

| Other sed/hyp/tranq. | |||

| Past 30 days | 1.14 (5.66) | 1.61 (5.38) | 2.09 (5.59) |

| Lifetime | 0.11 (0.31) | 2.00 (4.37) | 1.12 (2.52) |

|

| |||

| Cocaine | |||

| Past 30 days | 2.79 (4.35) | 3.84 (7.16) | 2.82 (5.57) |

| Lifetime | 3.96 (6.37) | 5.18 (6.73) | 4.21 (6.93) |

|

| |||

| Amphetamines | |||

| Past 30 days | 0.14 (0.76) | 0.24 (0.79) | 0.21 (0.78) |

| Lifetime | 0.39 (1.19) | 1.27 (2.85) | 1.76 (3.97) |

|

| |||

| Cannabis | |||

| Past 30 days | 2.75 (7.11) | 1.09 (2.16) | 3.73 (8.41) |

| Lifetime | 6.71 (6.15) | 8.48 (10.11) | 9.82 (10.59) |

|

| |||

| Hallucinogens | |||

| Past 30 days | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.12 (0.48) |

| Lifetime | 0.61 (1.19) | 0.94 (1.89) | 2.21 (3.32) |

|

| |||

| Inhalants | |||

| Past 30 days | 1.07 (5.67) | 0 (0) | 0.12 (0.42) |

| Lifetime | 0.36 (1.89) | 0.15 (0.87) | 0.21 (0.78) |

|

| |||

| More than one substance per day (Including Alcohol) | |||

| Past 30 days | 10.86 (10.91) | 6.16 (8.31) | 7.73 (9.77) |

| Lifetime | 6.36 (7.51) | 5.58 (7.38) | 7.09 (9.55) |

|

| |||

| Number of times treated for alcohol abuse in lifetime | 0.04 (0.19) | 0.61 (3.48) | 0.48 (1.69) |

|

| |||

| Number of times treated for drug abuse in lifetime | 2.50 (2.19) | 4.69 (8.29) | 4.42 (5.48) |

Opioid Use

Table 3 shows that at the end of 9 weeks there was no significant difference across treatment sites in the number of opioid-negative urine tests as measured by the TES (F=1.96; p = 0.15). Similarly, there was no difference among the treatment sites in TES at the end of 20 weeks (F = 2.64; p = 0.08).

Table 3.

Main Study Findings by Treatment Site

| OTP (n = 28) | PCS (n = 33) | MMM (n = 33) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opioid Use - TES | ||||

| Week 9 | 0.21 (0.26) | 0.16 (0.22) | 0.29 (0.35) | F = 1.96; p = 0.15 |

| Week 20 | 0.22 (0.27) | 0.17 (0.24) | 0.33 (0.37 | F = 2.67; p = 0.08 |

| Mean Dose | 21.92 (2.96) | 18.10 (4.80) | 20.97 (3.63) | F = 5.91; p = 0.00 |

| Retention | ||||

| Present at Week 9 | 53.57% | 39.39% | 54.55% | Chi-sq = 1.86; p = 0.39 |

| Present at Week 20 | 21.43% | 33.33% | 51.52% | Chi-sq = 6.12; p = 0.05 |

| # weeks retained | 13.96 (14.96) | 18.52 (21.77) | 24.85 (22.09) | F=2.26; p=0.1097 |

| Treatment Participation | ||||

| # Counseling Sessions | 8.91 (median = 7) | 7.06 (median = 5) | 6.13 (median = 6) | F=0.64; p=0.53 |

| # Counseling Minutes | 17.49 (median = 16.25) | 35.98 (median = 30.0) | 30.0 (median = 30) | F = 33.65; p < 0.00 |

Dose

Significant differences were found for mean dose prescribed to participants by treatment site (F = 5.91;p = 0.00). Table 3 shows that participants at the PCS site were prescribed significantly lower doses than those at both OTP and MMM sites.

A significant association was found between TES and prescribed dose. The correlation between the TES at 9 weeks and mean dose over the entire study duration was −0.40 (p = 0.00), and the correlation between the TES at 20 weeks and mean dose over the entire study duration was −0.41 (p = 0.00), indicating that higher dosage is associated with a lower percentage of opioid-negative urine test results.

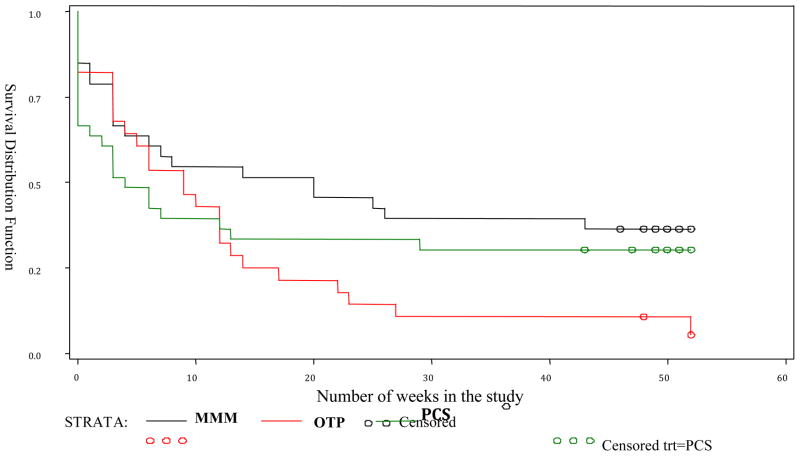

Retention

Retention was analyzed in two ways. One method compared the proportion of participants at each treatment site who stayed until the end of the two target time periods of 9 and 20 weeks. The second method computed the number of weeks in treatment at each site before drop out.

Table 3 provides the results of analyses comparing the number of participants who stayed in the study through weeks 9 and 20. No difference was found in retention through Week 9 by treatment site (chi-square = 1.86; p = 0.39), however the proportion of participants who stayed in the study through Week 20 was significantly associated with treatment site (chi-square = 6.12; p = 0.05) with the MMM site associated with the highest percentage of participants retained through week 20 (51.5%). Table 3 also shows the mean number of weeks that participants in each treatment condition remained in treatment, differences that were not statistically significant. Comparing the number of weeks in the treatment-by-treatment condition by using proportional hazards model shows that for participants who remained in the study past 9 weeks, OTP participants had a 4 times higher drop-out rate compared to MMM participants (p = 0.01), and a 6 times higher drop-out rate compared to PCS participants (p = 0.01). There was no difference in the percentage of participants at the PCS and MMM sites who remained in treatment for more than 9 weeks.

The number of weeks a participant remained in the study was significantly associated with opioid use as measured by the TES at both 9 weeks (r = 0.48; p < 0.00) and 20 weeks (r = 0.58;p < 0.00). That is, a higher percentage of opioid-negative urine test results was associated with longer treatment retention at both 9 and 20 weeks. After controlling for treatment site, a significant association remained between the TES at 9 weeks and number of weeks retained in the study (F = 10.17; p < 0.00). The results were similar for the TES at 20 weeks and the number of weeks retained in the study (F = 17.48; p < 0.00).

Addressing treatment site, the TES at 9 weeks was significantly associated with number of weeks in the study for the PCS (r = 0.43;p = 0.01) and MMM sites (r = 0.59;p = 0.00), but not the OTP site (r = 0.29; p = 0.12). The TES at 20 weeks, however, was associated with number of weeks retained in the study for all three treatment sites, OTP (r = 0.42; p = 0.03), PCS (r = 0.50; p = 0.00), and MMM (r = 0.72; p < 0.00).

A total of 24 (25%) of the randomized participants completed 52 weeks of treatment. Of the completers, 12 were in MMM, 10 were in PCS, and 2 were in OTP. Follow-up assessments were collected from 26 participants regarding reasons for not completing 52 weeks of treatment. Of the 26, 12 participants reported that they were no longer interested in buprenorphine treatment, with 5 of the 12 reporting that they lost interest on the first day of treatment. Other reasons for termination included: four administrative discharges for failure to keep clinic appointments, two participants developed medical problems unrelated to buprenorphine, two individuals were incarcerated, three participants requested detoxification, one went to the hospital with concurrent psychiatric problems, and two participants tapered off buprenorphine after 98 and 182 days of treatment.

Treatment Participation

A total of 64 participants received some form of psychosocial counseling during their participation in the study, with individual counseling occurring most often. A small number of participants attended other types of counseling such as group sessions, NA or AA meetings, or AIDS counseling. The importance of psychosocial counseling was examined by analyzing possible differences in the number of sessions attended and the number of minutes attended by participants at each treatment site.

Table 3 shows that the mean number of counseling sessions attended was not significantly different across the three sites, but the mean number of minutes spent in each individual counseling session was significantly different across treatment site (F = 33.65; p < 0.00). There was a significant correlation between the number of weeks the participant stayed in the study and the mean number of individual counseling sessions attended (r = 0.31; p = 0.02), such that longer retention was associated with a greater number of counseling sessions attended. There was also a significant correlation between the mean number of individual counseling sessions attended and the TES at 20 weeks (r = 0.26; p = 0.05), such that a greater number of individual counseling sessions was associated with a higher percentage of opioid-negative urine test results.

Qualitative Information: Site Experiences and Study Feasibility

At the primary care office setting (PCS), patients were allowed to reschedule missed appointments due to problems with transportation, work schedule and childcare. Trying to accommodate the patients' schedules led to physician and staff frustration. Fitting late patients into the schedule led to a pattern of patients being chronically late. The physician’s office staff was satisfied with conducting the on-site analysis of urine test using the urine cups. The cups allowed the monitoring of the patients’ progress without requiring access to a laboratory.

At the CBT clinic (MMM), which had been a medication-free setting, there was a concern about introducing opioid-dependent patients taking a maintenance medication into the clinic environment. Because not all clinic policies were determined in advance of treatment, staff were troubled that the physician provided prescriptions for buprenorphine even when participants did not attend all the group therapy sessions scheduled. The study patients were not integrated into groups with other substance users but congregated among themselves, causing less of a problem than anticipated, although one prescription opioid user became an injection user in the context of befriending heroin users in the group.

Physicians at the OTP site benefited from established site procedures in treating and monitoring the population. Staff was familiar with administering and interpreting urine tests, as well as performing random callbacks of medication.

Discussion

This study was conducted prior to the FDA approval of buprenorphine in 2002 and is the first study to report on the provision of buprenorphine in three distinct treatment settings: a group therapy program, a physician's primary care office, and an opioid treatment program. Findings were similar for participant opioid use and treatment participation across sites, but indicate significant differences in retention across sites. Although comparative treatment effectiveness could not be determined due to high drop-out rate, the different advantages and challenges experienced at the three sites offer useful insights for the creation of successful programs. Additionally, although the efficacy of buprenorphine in the treatment of opioid dependence has previously been established in placebo-controlled and open-label trials (Johnson et al., 1995; Fudala et al., 2003), the open-label study reported here supports the conclusion that buprenorphine is an important medical intervention in a population of predominantly injection heroin users.

Treatment Settings

The group therapy program at the MMM site was the most novel setting for examining the implementation and outcomes of buprenorphine treatment in this study. Historically, treatment for opioid dependence using maintenance medication (i.e., methadone) has been a controversial modality in group support programs, such as 12-Step groups, because it is seen as the continued use of an addictive drug. Additionally, intensive outpatient group therapy programs such as those provided at the MMM site have been considered "drug free" programs in contrast to methadone treatment. As expected, there was the greatest tension between clinic staff and the physician related to assumptions about the patients and their behaviors. Clear guidelines related to patient attendance, buprenorphine treatment, and urine test results initiated and implemented could have eased this tension.

A significant issue emerging in the MMM group counseling setting was the fact that a patient who was dependent on prescription opioids experimented with intravenous heroin use in the context of a "friendship" with another study participant which arose through long-term group participation. This is particularly relevant today as prescription drug use is increasing nationwide, and several investigators have described individuals progressing from prescription opioids to heroin because heroin is more accessible and less expensive (Siegal et al., 2003). As the numbers of prescription opioid users are increasing at treatment programs, possible risk reduction practices may include education about the risk of progression to heroin use in the context of the group therapy or if feasible a trial of separating users of different drugs into different treatment groups.

Implementing buprenorphine treatment in primary care office settings has been demonstrated to be relatively straightforward (Mintzer et al., 2007), and results from this study adds to this evidence. The primary care setting has the advantage of decreasing interaction with other drug users, and the practice can be easily replicated in diverse geographical areas in order to increase the availability of treatment (Fiellin et al., 2004). Initial efforts to engage patients into opioid treatment may require accommodating patients who are late or miss an appointment. Late patients are a common occurrence in any physician's practice, although many of the heroin-dependent patients in this study had a chaotic lifestyle that increased difficulties in adhering to a schedule, particularly early in treatment. Proactive practices that anticipated late arrivals, with standard policies and scripts that went into effect upon the initial late office visits as well as avoiding repeated accommodations and reinforcement of late arrivals would have lessened the frustration experienced by staff. Finally, it was notable that urine testing using on-site test cups provided rapid results that could be easily incorporated into the physician visit.

The OTP site had the benefit of a long-established treatment and monitoring system for individuals with opioid dependence, making personnel there familiar with the procedures required in handling this difficult-to-treat population. The clinic staff and physician in this study were also familiar with administration and interpretation of urine screens and random callback of medication. The OTP clinic adhered to an inflexible schedule however, which constrained some individuals from participating. OTP’s can dispense buprenorphine from a window similar to the practice of a methadone clinic or, as in the case of this study a program physician can provide buprenorphine via prescriptions filled at a pharmacy. Unfortunately, some patients reported that there is a stigma associated with methadone treatment programs and that such facilities attracted drug dealers seeking to take advantage of addicted individuals.

Retention and Treatment Effectiveness

Twenty-two percent of the participants dropped out of the study within the first three days of treatment, which illustrates the importance of early engagement of patients in treatment due to the risk of dropout within the first week of treatment. Some of the dropout that occurred may be due to the fact that this study was conducted before buprenorphine was approved by the FDA, and before buprenorphine earned a reputation as an effective treatment for opioid dependence. None of the patients had a history of buprenorphine treatment and few of the patients had heard of the medication. Poor retention within the first week of buprenorphine treatment has also been attributed to slow induction (Fischer et al., 1999; Mattick et al., 2003; Mueller et al., 2007). In this study, the average first day induction dose was 8mg, the dose listed in the package insert. This dose generally suppressed withdrawal symptoms and no ancillary medications were provided. A recent consensus statement on treatment with buprenorphine encourages the use of ancillary medication during induction to suppress the unmanaged symptoms of withdrawal (Fiellin et al., 2004). Offering ancillary medication may have increased retention during the first week of treatment. An important area of study is how to avoid imposing undue burden on providers in the course of improving retention of patients. Early study dropout decreased the sample size to a point where a statistical comparison of the three settings was problematic.

One-quarter of the patients completed 52 weeks. As in a typical clinical setting, patients were recruited with different goals: detoxification or maintenance. The protocol specified six weeks of treatment followed by a buprenorphine taper. No patients elected to initiate a taper after six weeks. Notably, all participants wanted to continue treatment and only at a later time period did three patients elect to detoxify or taper off study medication. The dropout rate was 48%, after the initial attrition of 22% within the first week of the study. At the OTP, this may have been due to limited clinic hours. Other reasons for dropout may have also included logistic problems, such as transportation to the clinic and/or pharmacy, and work schedule conflicts.

Half of the 10 couples completed the study. Treatment providers are often negative about the prognosis of heroin-using couples. However, the interpersonal support that couples provide can be tapped for its potential in shaping pharmacological and behavioral intervention efforts. Ideally, treatment providers can establish policies that recognize the existence and importance of opioid-dependent couples, and work with them to coordinate simultaneous treatment for both partners (Simmons & Singer, 2006).

None of the treatments had a markedly significant effect on decreasing opioid use, although there was a trend toward improvement at the MMM site. The lack of significance does not provide an indication that any of the three psychosocial services were inappropriate. Instead, these findings have implications for the treatment of opioid dependence with buprenorphine. In this sample of primarily heroin-dependent patients, cocaine use remained a problem, with 20% to 30% of participants intermittently testing positive for cocaine, although all participants denied dependence on another drug at admission. Patients who repeatedly use cocaine or other drugs may need to be referred to a higher level of care. Furthermore, the populations of patients initially studied in the development of buprenorphine were dependent on heroin, whereas a large percentage of the patients treated in office-based treatments today are dependent on prescription opioids. Current populations of patients treated with buprenorphine for opioid dependence may respond to different psychosocial interventions, such as contingency management with motivational incentives, which have been shown effective in recent research (Prendergast et al., 2006). Notably, Moore and colleagues have shown that prescription opioid dependent patients had a more favorable treatment response in the primary care office setting, compared to heroin users (Moore et al., 2007).

Retention in treatment has been associated with decreased drug use over time. In this study, retention in treatment was associated with a significant decrease in opioid use at all three treatment sites at the 20 week assessment, and at the PCS and MMM sites at the 9 week assessment. A study with a larger sample size, which also analyzes cost-effectiveness, would be necessary to determine the potential added benefits to the more costly service, such as weekly group therapy, individualized therapeutic interventions by a physician (a psychiatrist in this case) or by a drug counselor.

Limitations

There are a number of limitations to this study. Foremost among these limitations was the underpowered nature of the study. Although the drop-out rate was higher than expected, it seems likely that too few subjects were recruited to sufficiently power a comparison between treatment settings; the high drop out rate exacerbated these effects. The open-label nature of the study limited analysis of the effectiveness of buprenorphine as a treatment, as did the variation in prescription practice by site. Further studies to compare the effectiveness of different settings are recommended, with sufficiently large initial populations, and measures in place to limit drop-out rates.

Conclusion: Buprenorphine Treatment

Buprenorphine is a relatively new treatment innovation that can be implemented in a number of different settings where opioid dependence has not been traditionally addressed. Although over 18,000 physicians have received approval to prescribe buprenorphine, its use has not yet been widely adopted by physicians and substance abuse treatment centers in the United States. Some physicians have been reluctant to integrate buprenorphine into office-based practice citing barriers such as lack of sufficient training in addiction, medication, cost, psychosocial service requirements, and limited ancillary support (Barry et al., 2009; SAMHSA, 2006). Organizational factors (e.g., staffing, structure) and provider characteristics (e.g., attitudes about medication-assisted treatment) have been shown to differentially impact buprenorphine adoption and implementation among private and public addiction treatment programs (Fitzgerald & McCarty, 2009; Roman et al., 2006), with private centers more likely to integrate addiction pharmacotherapies than public centers (Roman et al., 2006).

The lessons learned from implementation of buprenorphine in the three treatment sites in this study are fundamental and may be applicable to other practices of these three setting types. Although it is worth noting that this study was conducted before FDA approval, initial education of the staff in all three settings about the utility of buprenorphine was crucial. This was particularly true at the MMM program where the staff advocated an abstinence approach to treatment. In addition to a shift in attitude, modifications of practice management were necessary, such as implementing a monitored induction protocol, on-site drug testing and random pill callback checks. The study staff all indicated that they would have made additional refinements in patient management practices, had they not been confined by a research protocol. These refinements in management practices are noteworthy.

The initial refinement, which may have optimized successful outcomes, was to give careful consideration to patient complexity prior to initiation of treatment. This study accepted opioid-dependent patients without extensive prescreening for polysubstance use and psychosocial resources for sobriety. Treating individuals committed to abstinence with social and occupational resources can improve outcome. The key factor after patient selection is engagement and retention in treatment. Previous research reports have shown that during the first 30 days there is the greatest risk for dropout (Stein et al., 2005). Early engagement in treatment may be facilitated by regular one-on-one contact with the patients, including frequent visits, regular telephone contact and appointment reminders. Stein and colleagues reported that early abstinence in treatment and participation in counseling predicts a favorable response to buprenorphine treatment (Stein et al., 2005). Conversely, relapse to opioids or other illicit drugs are commonly seen before patient dropout. On-site drug testing allows prompt feedback and adjustments in the treatment plan. Initial signs of on-going drug use should not be overlooked; instead a modification of the treatment process can be implemented, such as increasing the frequency of counseling or office visits, or 12-Step participation.

Participants were not terminated from the study for positive drug screens, as long as some improvements in functioning were noted by the study physician and patient. However, in many settings “leveraged treatment” may be beneficial. Examples of leveraged treatment would be where the provider requires that the patient enter a higher level of care, such as frequent 12-Step meetings or a residential treatment program as a condition of ongoing buprenorphine treatment.

Special attention must be given to the risk of conversion from prescription opioids to heroin use. As evidence in the Siegal et al. investigation (2003), conversion from prescription drug abuse to heroin abuse is a risk and “suggests that the abuse of opioid analgesics constitutes a new route to heroin abuse, placing new populations at risk for heroin addiction. This is a reversal of the classic pattern in which heroin users would turn to prescription opioids when heroin was unavailable.” Having buprenorphine available in diverse settings will ideally help prevent patients from making the transition from prescription opioid use to injection heroin use.

Treatment of opioid dependence with buprenorphine includes the responsibility to monitor for diversion. It became clear during this study that diversion monitoring was less familiar to the primary care provider and MMM staff but a routine activity at the OTP site. At the time of this study, an easy dipstick urine assay for buprenorphine was not available. However, asking patients to bring in their medication on a day other than their scheduled visit to count the number of pills was employed as a diversion safeguard. An insufficient number of pills may suggest a pattern of use other than the one prescribed, or possible diversion. If the patient has more buprenorphine tablets over what they should have, one recommendation would be to lower the patient’s dose of medication. Similarly, if a patient misses visits but is doing well, it may be because they are taking less medication. It is understandable that a patient may want to save medication for a "rainy day supply" but keeping large stores of medication adversely alters the treatment process and increases the risk of diversion. Patient-physician trust should be built on objective verifiable measures and urine drug testing. Clinician not familiar with treating addicted patients need to learn that similar to poor boundaries, lying about medication and drug-related matters can be conceived as a survival skill before the individual develop a recovery program.

Essentially, buprenorphine proved to be a relatively easy treatment to implement in the three diverse settings of this study. Included were treatment settings where opioid dependence has not been traditionally treated: the physician office, and a group therapy treatment setting. Although treatment dropout is a potential problem with opioid-dependent individuals, study patients and physicians reported subjective improvement in all three settings. Future research is necessary, however, to further identify psychosocial strategies and approaches for optimizing outcomes.

Figure 1.

Number of weeks retained in the study by treatment group

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This work was supported by the National Institute of Drug Abuse grant 1 DA P-50 09260 and P-50 DA 12755

List of References

- 1.Hser YI, Hoffman V, Grella CE, et al. A 33-year follow-up of narcotics addicts. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:503–08. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.5.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration (SAMHSA) Overview of Findings from the 2002 National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2002. 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ling W, Shoptaw S, Wesson D, et al. Treatment effectiveness score as an outcome measure in clinical trials. NIDA Res Monogr. 1997;172:208–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) FDA Talk Paper. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kakko J, Svanborg KD, Kreek MJ, et al. 1-year retention and social function after buprenorphine-assisted relapse prevention treatment for heroin dependence in Sweden: a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;361:662–68. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12600-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Psychiatric Association (APA) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 3. 1987. Revised: DSM-III-R. [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCann M, Obert J, Ling W. Buprenorphine Treatment of Opioid Addiction: A Counselor's Guide. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bogema SC. Performance Evaluation of the Roche Diagnostic Corporation Ontrak Testcup-5 for Screening of DHHS Five Drugs in Urine. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cacciola JS, Alterman AI, O'Brien CP, et al. The Addiction Severity Index in clinical efficacy trials of medications for cocaine dependence. NIDA Res Monogr. 1997;175:182–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ling W, Charuvastra C, Collins JF, et al. Buprenorphine maintenance treatment of opioid dependence: a multicenter, randomized clinical trial. Addiction. 1998;93:478–86. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.9344753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson RE, Eissenberg T, Stitzer ML, et al. A placebo controlled clinical trial of buprenorphine as a treatment for opioid dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1995;40:17–25. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(95)01186-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fudala PJ, Bridge TP, Herbert S, et al. Office-based treatment of opioid addiction with a sublingual- tablet formulation of buprenorphine and naloxone. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:949–58. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mintzer IL, Eisenberg M, Terra M, et al. Treating opioid addiction with buprenorphine-naloxone in community-based primary care settings. Ann Fam Med. 2007:146–50. doi: 10.1370/afm.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fiellin DA, Kleber H, Trumble-Hejduk JG, et al. Consensus statement on office-based treatment of opioid dependence using buprenorphine. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2004;27:153–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Siegal HA, Carlson RG, Kenne DR, et al. Probable relationship between opioid abuse and heroin use. Am Fam Physician. 2003;67(942):945. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fischer G, Gombas W, Eder H, et al. Buprenorphine versus methadone maintenance for the treatment of opioid dependence. Addiction. 1999;94:1337–47. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.94913376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mattick RP, Ali R, White JM, et al. Buprenorphine versus methadone maintenance therapy: a randomized double-blind trial with 405 opioid-dependent patients. Addiction. 2003;98:441–52. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mueller SE, Petitjean S, Boening J, et al. The impact of self-help group attendance on relapse rates after alcohol detoxification in a controlled study. Alcohol Alcohol. 2007;42:108–12. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agl122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simmons J, Singer M. I love you... and heroin: care and collusion among drug-using couples. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2006;1:7. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prendergast M, Podus D, Finney J, et al. Contingency management for treatment of substance use disorders: a meta-analysis. Addiction. 2006;101:1546–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moore BA, Fiellin DA, Barry DT, et al. Primary care office-based buprenorphine treatment: comparison of heroin and prescription opioid dependent patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:527–30. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0129-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barry DT, Irwin KS, Jones ES, Becker WC, Tetrault JM, Sullivan LE, Hansen H, O’Connor PG, Schottenfeld RS, Fiellin DA. Integrating buprenorphine treatment into office-based practice: A qualitative study. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2009;24:218–25. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0881-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA. [Accessed March 2010];Evaluation of the Buprenorphine Waiver Program. 2006 at http://buprenorphine.samhsa.gov/evaluation.html.

- 24.Fitzgerald J, McCarty D. Understanding attitudes toward use of medication in substance abuse treatment: A multilevel approach. Psychological Services. 2009;6:74–84. doi: 10.1037/a0013420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roman PM, Ducharme LJ, Knudsen HK. Patterns of organization and management in private and public substance abuse treatment programs. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2006;31:235–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stein MD, Cioe P, Friedmann PD. Buprenorphine retention in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:1038–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0228.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]