Abstract

Aim:

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of disfigurement due to cancer and its treatments on quality of life.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 120 patients from the inpatient/outpatient department of oncology who had undergone various forms of treatment for cancer were included in this study. The WHOQuality of Life BREF (WHOQL-BREF) version was administered to the patients to assess their quality of life.

Results:

Patients’ overall quality of life score ranged from 34 to 79 with an average of 53.18 (SD 11.94) and a large number of patients had scored from 40 to 54 on the WHOQOL-BREF.The study showed a significant difference between gender groups (t = 3.899, P < 0.05), with a significant difference in the mean quality of life between different categories of the prominent stigma (f = 4.018, P < 0.05) and the nature of stigma. Disfigurement clearly was a stressful experience for both sexes, but substantially more distressing for women. Majority of the patients experienced poor quality of life in all dimensions, namely, physical health, psychological health, social relationships, environmental health, and other sociodemographic variables.

Conclusion:

Living with a disfiguring body which is visibly different is not always easy. A sudden change either due to cancer or its treatment or due to side effects leads to significant social maladjustment, elevated anxiety, depression, and poor quality of life among the cancer survivors with body disfigurement which calls for multiprofessional involvement in addressing various psychosocial issues.

Keywords: Cancer, Disfigurement, Quality of life

INTRODUCTION

Though modern medical treatments provide hope for thousands of cancer patients, cancer treatment may result in long-term physical and appearance-related changes such as removal of a body part or scarring, swelling, weight changes, skin color changes, sunburn, hair loss, and other side effects. Apart from physical and appearance changes due to cancer and its treatments which cause disfigurement, there are also some unpleasant side effects such as fatigue/weakness, infections, loss of appetite, nausea and vomiting, mouth sores, hot flushes, loss of fertility, interrupted menstrual periods, fever, muscle aches, diarrhea, and constipation. Majority of the cancer treatments cause mild/moderate to severe disfigurement.[1]

Changes to appearance as a result of cancer and its treatment can have a far-reaching impact. Not only can they act as vivid, constant reminders of the cancer but looking and/or feeling visibly different can also have a detrimental impact on quality of life including reduced self-confidence, low self-esteem, difficulty with social interactions, and ultimately social withdrawal.

Impact of disfigurement

Visible disfigurements can have a profound psychosocial impact upon the individual concerned. Difficulties include adverse effects on body image, quality of life, and self-esteem. In addition, social encounters can present many challenges; however many individuals adapt to the demands placed upon them and appear relatively unaffected by their visible difference. It is well known that normal appearing members of a species group will reject other members who appear abnormal for their group.[1]

For a person born with a disfigurement, psychological effects may occur at many stages, from very early childhood through to adulthood. The social and cognitive processes during the early years of child's life, in relation to how his or her family, friends, and others around react to the disfigurement, will affect his or her self-esteem, sense of worth, and self-confidence (coping with other people and situations). These may result in low expectations later in life regarding relationships and work. A visible difference can have a profound psychosocial impact, and people with a disfigurement often have emotional, social, and economic difficulties. This is in addition to those associated with the medical treatment. Self-esteem, body image, and quality of life can be adversely affected.[2] The psychological and emotional effects of a changed appearance may result in social isolation and a process of bereavement for the loss of a patient's former face and identity.

A study conducted by Williamson et al.[3] to quantify the effect of hair loss on quality of life found a significant impact. Van Der Donk et al[4] found that hair loss has a negative influence on the quality of life; in 88% persons, hair loss had negative effects on their daily life; in about 75%, the hair problems were manifested in negative self-esteem and about 50% experienced social problems. General psychosocial maladjustment in relation to hair loss was indicated in almost one-third of the women. Alopecia has been cited as the most disturbing anticipated side effects in up to 58% of women preparing for chemotherapy, with 8% being at risk for avoiding treatment.[5] Women with cancer with alopecia report lower self-esteem, poorer body image, and lower quality of life.

Disfigurative facial surgery was associated with extremely high levels of anxiety, and body image reintegration is critical to subsequent quality of life after head and neck cancer surgery.[6] Chaturvedi et al.[7] showed that the commonest concerns are subjective physical evaluation social interactions, pain, and disfigurement among patients with oral and laryngeal cancers. Newell and Marks[8] found that psychological disturbance, hospital anxiety, and depression were greater in facially disfigured people than in the general population. Rumsey[9] found that patients with a variety of disfiguring conditions had unfavorable levels of anxiety, depression, social anxiety, social avoidance, and quality of life compared to published norms in outpatients. Pruzinsky[10] showed that the effects of reconstructive surgery on the body image are complex, involving physical, psychological, and social variables. In subscribing to the biomedical view of a simple relationship between appearance and adjustment, care providers are colluding with the myth that quality of life necessarily improves when the physical appearance is enhanced[11] People found with disfiguring conditions need resources to support successful adjustments to their appearance and enhance quality of life.

Rumsey et al.[12] undertook a study to establish the extent and type of the psychosocial need in attending outpatients for treatment for a variety of disfiguring conditions and found that a considerable proportion of the outpatients with disfiguring conditions experienced psychosocial difficulties, displaying raised levels of anxiety, depression, social anxiety, and social avoidance, and reduced quality of life. Levels of psychosocial distress were not well predicted by the severity of disfigurement. Various disfiguring conditions seen at 6 week preoperativeand 3 month postoperative appointments using, standardized measuresof anxiety and depression (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale),social anxiety (Derriford Appearance Scale), and quality oflife (WHOQOL-BREF)[13] were administrated. Results show preoperatively, levels of depression were comparableto relevant population norms; however, levels of general anxietywere slightly raised and levels of social anxiety and socialavoidance were significantly poorer than population norms. Thousands of people are affected by disfigurement due to injury, disease, treatment, and its side effects. Society's obsession with appearance can marginalize those who appear different. Thousands of children, adolescents, and adults who are visibly different face enormous challenges in our current appearance-oriented society. Surgery and medicine can rarely completely remove their disfiguring marks and not affordable to many in developing countries. Many people who are living with a visible difference cope very well with the challenges they face but many others experience considerable levels of concern and distress that can negatively impact quality of life. In addition, a large proportion of the general public has significant appearance-related concerns. Thus it is essential that the psychological and social effects of appearance concerns are to be studied in order to assess what can be done to help those who are negatively affected to manage everyday problems.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The present study was conducted with an aim to evaluate the quality of life of persons with disfigurement due to cancer and its treatments. A sample comprising 120 patients of both male and female cancer survivors with body disfigurement due to cancer and its treatments in the age group of 18 and above was taken. Those patients satisfying the criteria and attending either outpatient or inpatient service at GKNM Hospital (Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, India) were selected using a simple random sampling method. Cancer survivors who had other physical disabilities or psychiatric problems were not included. The patients who fulfilled the inclusion and exclusion criteria were identified based on the information from the patient perusal of medical record, as well as discussion with the consultant oncologists.

Analysis of data

Data were expressed using descriptive statistics such as mean, standard deviation for continuous variables, and frequency and percentages for categorical variables. These were to understand the distribution of the sample on the sociodemographic and other variables, to assess the psychosocial consequences of body disfigurement. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to assess the extent of changes in the variables for quality of life. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

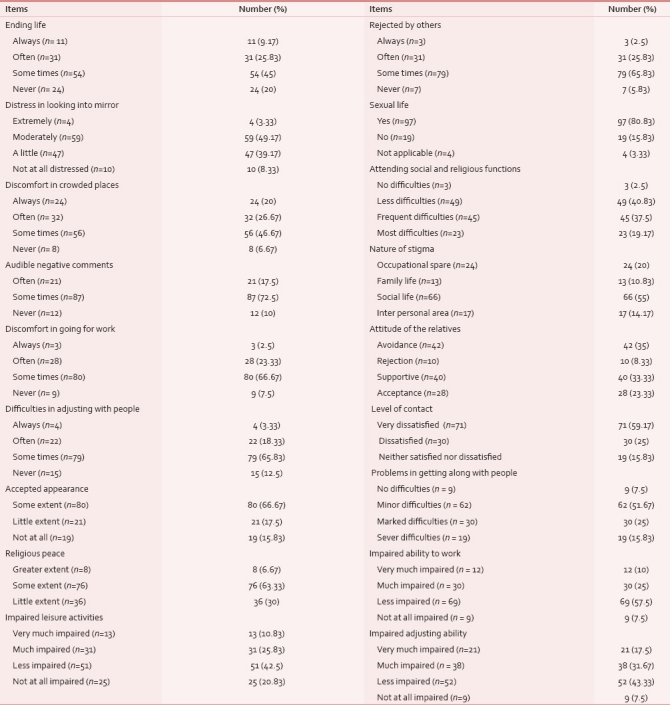

The WHOQOL-BREF provides with an understanding of the quality of life of the patients. Table 1 provides a detailed distribution of disfigured cancer patients’ response to items on different areas of problems and adjustment. Among the patients, majority (80.8%) reported a poor quality of life and more than half (58.3%) of the patients were very dissatisfied with their health condition. A considerable number (47.5%) of them were satisfied with their conditions of the living place. But only 33.3% of them were satisfied with the access to health services. Majority (59.2%) of the patients experienced a poor quality of life because of physical pain which prevented them doing what they needed to do; similarly, 67.5% of the patients experienced a poor quality of life related to enjoyment of life. More than half (55.0%) of the patients experienced a poor quality of life for item “To what extent do you feel your life to be meaningful”. Majority (74.2%) of the patients experienced a poor quality of life related to their ability to concentrate and 60.0% of the patients experienced a very poor quality of life related to their feeling of safety in daily life. A considerable number (39.2%) of the patients experienced a poor quality of life related to their healthy physical environment.

Table 1.

Patients’ response to items for different areas of problems and adjustment

Majority of the patients experienced a poor quality of life related to the energy for everyday life (62.5%), ability to accept their bodily appearance (65.0%), enough money with which to meet out their needs (41.7%), opportunities for leisure activities (58.3%), ability to get around (67.5%), dissatisfaction with sleep (70.8%), dissatisfaction with ability to perform daily living activities (53.3%), dissatisfaction with their capacity to work (87.1%), dissatisfaction with themselves (65.0%), dissatisfaction with their sexual life (62.5%), the support they received from friends (38.3%), and frequency of having negative feelings such as blue mood, despair, anxiety, depression (35.0%). More than half (86.7%) of the patients experienced an average quality of life related to the availability of information needed in day-to-day life [Table 2].

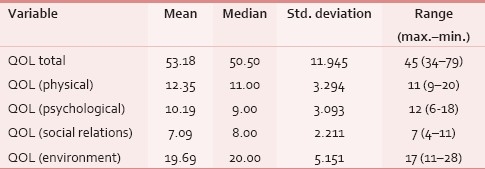

Table 2.

Summary statistics for the WHOQOLBREF scale and its domains

Patients’ overall quality of life score ranged from 34 to 79 with an average of 53.18 and a standard deviation of 11.94. This indicates that on an average, the quality of life of the patients was fairly good on the WHOQOL-BREF, as the higher the score the better is the quality of life. The domain scores indicate that the physical domain had an averages score of 12.35 with a standard deviation of 3.294 and the psychological domain had an average score of 10.19 with a standard deviation of 3.094. The patients however had a lower score in the social relations domain with an average score of 7.09 and a standard deviation of 2.211. Finally, in the environment domain, the patients had an average score of 19.69 and a standard deviation of 5.151 [Table 3].

Table 3.

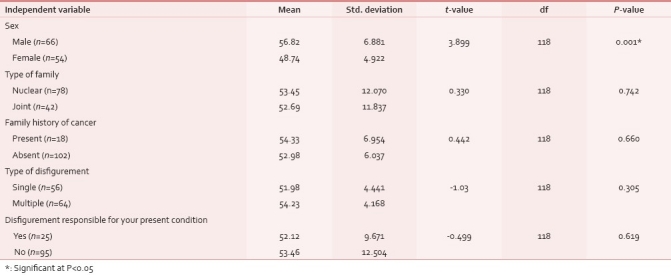

Difference in mean values for quality of life and with socio demographic variables

Patients’ response on the scales of quality of life was analyzed using Student's t-test to find out if there was any significant difference between the sociodemographic variables and the scores on the scale.

The score on the quality of life scale was found to be significantly different only between genders in its mean quality of life (t = 3.899, P < 0.05). Male patients’ mean score (56.82)was higher for quality of life than female patients’ mean score (48.74; Table 4).

Table 4.

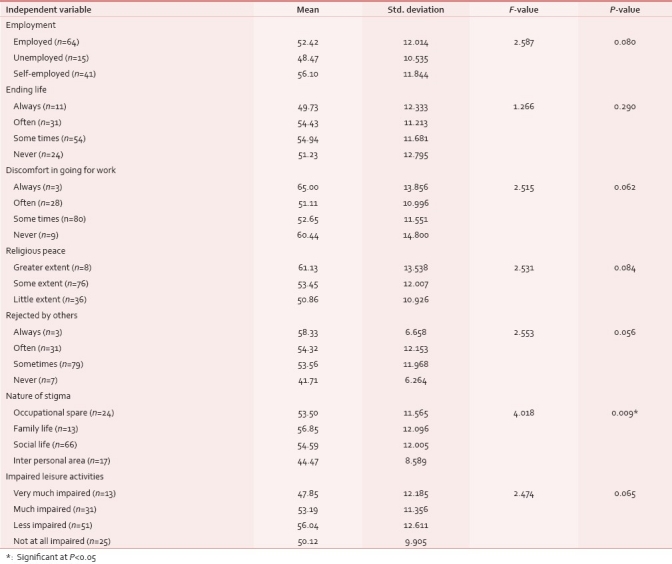

Difference in mean values for quality of life and sociodemographic variables

Patients’ response on the scales of quality of life was analyzed using ANOVA to find out if there was any significant difference between the sociodemographic variables and the scores on the scale. Patient's score on the quality of life scale was found to be significant only for two scores.

The patients showed a significant difference (F = 2.553, P < 0.05) between the means of the “people who felt like rejected by others after the appearance had altered” on the quality of life scale. Patients who felt like rejected by others always had a higher mean (58.33) than the patients (mean 41.71) who never felt like that.

Again, the nature of stigma showed a significant difference in its means for the quality of life (F = 4.018, P < 0.05). Patients who had experienced difficulties in theirfamily life (56.85)showed a higher mean on self-esteem than the rest of the spheres like interpersonal area (44.47).

DISCUSSION

The current study reveals that 51.7% of the patients were having minor difficulties in getting along with people after the appearance was altered which is supported by Chaturvedi et al,[7] in a study among 50 patients with head and neck cancer to explore the concerns and coping mechanisms used by patients and assess their quality of life. The results showed that the commonest concerns are social interactions. In addition to the above study, other western studies[14–17] also support this finding that social interaction is an area of life where difficulties may lie.

Further, Williamson et al.[3] identified feelings of loss of self-confidence, low self-esteem, and heightened self-consciousness in people affected by hair loss. Even a study conducted by McGarvey et al.[5] among women with cancer who experienced alopecia as a side effect, compared with women with cancer and no alopecia, reported lower self-esteem, poorer body image, and lower quality of life.

Quality of life of the patients

It would almost be natural to expect a poor quality of life and loss of normal life in any disfigurement population because of the living conditions. The objective of the present study is to explore the quality of life of the cancer survivors with body disfigurement.

The present study shows that patients’ overall quality of life score ranged from 34 to 79 with an average of 53.18 and a standard deviation of 11.94 and a large number of patients had scored 40–54 on the WHOQOL-BREF which shows that majority of the cancer survivor with body disfigurement had low self-esteem. This result of the current study is also similar to the findings of Rumsey[9] that among 650 consecutive outpatients attending for a variety of disfiguring conditions, quality of life had severely been affected. Similarly Van Der Donk et al.[4] studied quality of life and maladjustment related to hair loss in a group of 58 women with alopecia and showed that hair loss was found to have a negative influence on the quality of life for the majority of them.

This fact is substantiated by the studies[5] which show that women with cancer who experienced alopecia as a side effect, compared with women with cancer and no alopecia, reported poorer body image, and lower quality of life.

This is in agreement with the comments by Dropkin.[6] In a study among 75 surgical head and neck cancer patients, it was revealed that body image reintegration is critical to subsequent quality of life after head and neck cancer surgery. When disfigurement/dysfunction is associated with treatment, quality of life may be profoundly and adversely affected.

The other fact is reiterated;[18] patients with a visible difference exhibited significantly greater levels of disability, stigma, and poorer quality of life and evaluated their appearance more negatively. This has been proven by the study conducted by Rumsey et al.[2] among 220 outpatients attending for treatment for a variety of disfiguring conditions, who had psychosocial difficulties, displaying raised levels of anxiety, depression, social anxiety and social avoidance, and reduced quality of life. Similar results were reported by Kent and Keohane[19] in their study that noticeable disfigurement was the most relevant for quality of life. This was found to be true by Clarke et al.'s[20] study among 153 patients with noticeable disfigurement. It revealed that quality of life scores were also less favorable.

Patients in the present study showed a significant difference between gender groups (t = 3.899, P < 0.05), on mean quality of life. Disfigurement clearly was a stressful experience for both sexes, but substantially more distressing for women.

This may be due to the fact that the feelings of rejection by others may make a person inferior. If the feeling of inferiority persists, it may have an impact on the overall quality of life. In recent years, health psychologists have paid increasing attention to psychological adjustment associated with perceived abnormalities of appearance.[21] Research indicates that having a disfigured appearance is likely to elicit avoidant and socially awkward behavior in others.[14]

Patients in the current study showed a significant difference between the prominent nature of stigma (F = 4.018, P < 0.05), on mean quality of life. The other fact is reiterated by James et al.[18] who stated that patients with a visible difference exhibited significantly greater levels of disability, stigma, and poorer quality of life and evaluated their appearance more negatively. This may be the reason for someone's attitudes to disfigurement being prejudiced, stigmatizing, and uninformed. Having a facial impairment can lead to psychological and social difficulties because of the way the society reacts.

Pearson's correlation coefficient revealed that age is negatively and significantly correlated, with a fear of negative evaluation. It may also be that the young people may feel more anxious because of excessive importance given to appearance in the society. With age, bodily changes usually occur. It is a natural process of aging. Though the changes result from cancer and its treatment is not similar to the changes resulting from aging, the older age group would show less fear of negative evaluation compared to their counterpart which is in contrast to Robinson et al.,[22] who found no correlation of patient age or duration of disfigurement with levels of anxiety and depression.

CONCLUSION

The cancer patients suffer from substantial and long-term psychological distress associated with different forms of cancer and its medical treatments. Living with cancer can create a great deal of emotional stress, fear about treatment side effects, the fear of a relapse, and generalized distress that results from living with the day-to-day physical problems often associated with a cancer diagnosis and can create new or worsen existing psychological distress. In addition, both physical and psychological impairments can lead to significant social problems. Unfortunately, due to stress or recent lifestyle changes people are at a greater of having cancer diagnosis. Some of the treatments like chemotherapy, surgery, and radiotherapies are inevitable to treat cancer patients and the possible side effects and psychosocial consequences are also unavoidable in cancer treatments. Usually cancer and its treatments result in disfigurement is a state in which an individual's physical appearance is deeply affected. Living with a disfiguring body which is visibly different is not always easy. Cancer or its treatment's side effects may lead to significant social maladjustment, elevated anxiety and depression, and lowered quality of life among the cancer survivors with body disfigurements. Cancer survivors with a body disfigurement suffer from social and mental problems. These circumstances affect the long-term quality of life of the cancer survivors with body disfigurement.

The results of the study are indicating a need for mental health services by psychiatric social workers which may be individual, group, or community based. The decrease in quality of life calls for interventions at the societal and policy level so that the cancer survivors with body disfigurement are not considered inferior or second-class citizens. Programs at the community level will help the cancer survivors with body disfigurement in sustaining their culture so that they will feel connected and cohesive. Individual-, group-, and community-level interventions such as counseling, mental health awareness programs in the cancer center, etc., are the need of the hour.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.David L, Harris Cosmetic surgery-where does it begin? Br J Plast Surg. 1982;35:281–6. doi: 10.1016/s0007-1226(82)90114-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rumsey N, Clarke A, White P. Exploring the psychosocial concerns of outpatients with disfiguring conditions. J Wound. 2003;12:247–52. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2003.12.7.26515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williamson D, Gonzalez M, Finlay A. The effect of hair loss on quality of life. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:137–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2001.00229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Der Donk J, Hunfeld J, Passchier J, Knegt-Junk K, Nieboer C. Quality of life and maladjustment associated with hair loss in women with alopecia androgenetica. Soc Sci Med. 1994;38:159–63. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90311-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGarvey E, Baum L, Pinkerton R, Rogers L. Psychological sequelae and alopecia among women with cancer. Cancer Pract. 2001;9:283–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.2001.96007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dropkin M. Anxiety, coping strategies, and coping behaviors in patients undergoing head and neck cancer surgery. Cancer Nursing. 1999;24:143–8. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200104000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaturvedi SK, Shenoy A, Prasad KM, Senthilnathan SM, Premlatha BS. Concerns, coping and quality of life in head and neck cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 1996;4:186–90. doi: 10.1007/BF01682338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Newell R, Marks I. Phobic nature of social difficulty in facially disfigured people. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;176:177–81. doi: 10.1192/bjp.176.2.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rumsey N, Clarke A, Musa M. Altered body image: The psychosocial needs of patients. Br J Commun Nurs. 2002;7:563–6. doi: 10.12968/bjcn.2002.7.11.10886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pruzinsky . Body image: A handbook of theory, research, and clinical practice. New York: The Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Magee H. Meeting the information needs of people with conditions that affect appearance 3. Bristol. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rumsey N, Clarke A, White P. Exploring the psychosocial concerns of outpatients with disfiguring conditions. J Wound. 2003;12:247–52. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2003.12.7.26515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jackson S, Harrad R, Morris M, Rumsey N. The psychosocial benefits of corrective surgery for adults with strabismus. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90:883–8. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.089516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bull R, Rumsey N. The Social Psychology of Facial Appearance. New York Inc; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malt U, Ugland O. A long-term psychosocial follow-up study of burned adults. Acta Psychiatr Scand Vica Suppl. 1989;355:94–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1989.tb05259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.MacGregor F. Facial disfigurement: Problems and management of social interaction and implications for mental health. Aesthet Plast Surg. 1990;14:249–57. doi: 10.1007/BF01578358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Houston V, Bull R. Do people avoid sitting next to someone who is facially disfigured? Eur J Soc Psychol. 2006;24:279–84. [Google Scholar]

- 18.James H, Newman S, Shipley M, Moore S, Olaleye A. Appearance In the context of Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) does appearance matter.? Appearance Matters 3 conference. Bristol. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kent G, Keohane S. Social anxiety and disfigurement: The moderating effects of fear of negative evaluation and past experience. Br J Clin Psychol. 2000;40:23–34. doi: 10.1348/014466501163454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clarke A, Rumsey N, Collinand J, Wyn-Williams M. Psychosocial distress associated with disfiguring eye conditions. J Eye. 2003;17:35–40. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6700234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lansdown R, Rumsey N, Bradbury E, Carr A, Partridge J. Visibly different: Coping with disfigurement. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robinson E, Rumsey N, Partridge J. An evaluation of the impact of social interaction skills training for facially disfigured people. Br J Plast Surg. 1996;49:281–9. doi: 10.1016/s0007-1226(96)90156-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]