Abstract

Context:

Advances in expertise and equipment have enabled the medical profession to exercise more control over the processes of life and death, creating a number of moral and ethical dilemmas. People may live for extended periods with chronic painful or debilitating conditions that may be incurable.

Aim:

This study attempts to study the attitudes of doctors toward euthanasia and the possible factors responsible for these attitudes.

Settings and Design:

A cross-sectional survey of 213 doctors working at a tertiary care hospital was conducted to determine their attitudes toward euthanasia.

Materials and Methods:

A self-administered questionnaire was used to assess attitudes and personal perceptions about euthanasia.

Statistical Analysis Used:

The Chi square test was used to assess factors influencing attitudes toward euthanasia.

Results:

A majority of the respondents (69.3%) supported the concept of euthanasia. Relief from unbearable pain and suffering was the most commonly (80.3%) cited reason for being willing to consider the option of euthanasia. Majority of those who were against euthanasia (66.2%) felt that the freedom to perform euthanasia could easily be misused. Disapproval of euthanasia was associated with religious affiliation (P<0.001) and speciality (P<0.001).

Conclusions:

A majority of the doctors in this study supported euthanasia for the relief of unbearable pain and suffering. Religion and speciality appear to be significant in determining attitudes toward euthanasia.

Keywords: Attitudes, Doctors, Euthanasia

INTRODUCTION

Euthanasia, derived from a Greek term meaning “good death” refers to the intentional hastening of death of a patient by a physician with the intent of alleviating suffering.[1] Euthanasia may be carried out by administering drugs to cause death[2] (active euthanasia) or by withdrawing treatment that is essential to keep the patient alive[3] (passive euthanasia). Pain relief and sedation do not fall within the scope of euthanasia.[2,4] The issue of euthanasia has long been a matter of debate in medical, social, legal, and religious domains. Although usually carried out at the ailing person's request, the decision may be taken by relatives, doctors, or in some instances – as in the recent landmark judgement on Aruna Shanbaug – the courts. The present exploratory study was conducted at a tertiary care hospital in south India in order to learn the attitudes of doctors toward euthanasia and the possible factors responsible for these attitudes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This cross-sectional survey was conducted between March and April 2010 among medical interns, postgraduate trainees, and faculty members directly involved in patient care in various departments of a tertiary care teaching hospital in South India. A self-administered questionnaire was designed and validated by three specialists with expertise in palliative care and medical ethics.

The questionnaire was used to collect information on gender, age, religious affiliation, speciality, designation, and attitudes toward euthanasia. The respondents were asked to state whether they were for or against the concept of euthanasia; a distinction was not made between active and passive euthanasia. Information was also solicited on the reasons for approving or disapproving of euthanasia; the questionnaire listed some options for the approval or disapproval and also gave the provision for the respondent adding reasons not listed in the questionnaire.

Of the questionnaires distributed to a convenience sample of 250 doctors individually, 213 were returned resulting in a response rate of 85.2%. Respondents remained anonymous.

The statistical analysis for this survey was done using SPSS version 16.0 for Windows. The data analysis included demographic factors such as age, gender, and religion in an attempt to better understand the respondents’ attitudes regarding euthanasia. The Chi square test was used to assess factors influencing attitude toward euthanasia; P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Results are expressed in percentages.

RESULTS

Majority of the respondents were male (60.1%). Almost two-thirds of the respondents (65.3%) belonged to the age group of 21–30 years, and the mean (SD) age of respondents was 30 (7.84) years. Among the respondents 40.4% were faculty members, 31.5% were postgraduate trainees, and 28.2% were medical interns. Faculty and postgraduate trainees belonged to obstetrics and gynecology (27.2%), pediatrics (23.5%), surgical branches (9.4%), and medical specialties (8.9%). Regarding religious affiliation, Hinduism was the religion practiced by a majority of the respondents (79.3%) followed by Christianity (6.6%).

Majority (69%) of the respondents were in favour of the concept of euthanasia while 30% were against it; one respondent was undecided.

There was no significant difference in opinion regarding euthanasia between the genders (P = 0.66) and among various age categories (P = 0.41).

A significant association was observed between religious affiliation and negative attitude toward euthanasia (P< 0.001); with 10 out of 13 followers of Islam (76.9%) and 9 out of 14 of those practicing Christianity (64.3%) opposing euthanasia as compared to 41 of 169 respondents practicing Hinduism (24.3%). However, most of the respondents (75.9%) were of the opinion that their religious beliefs did not influence their views on euthanasia.

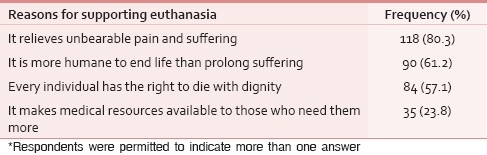

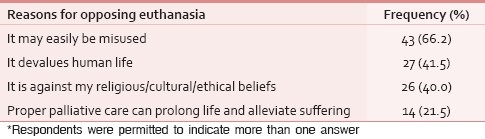

The reasons cited by the respondents for either supporting or rejecting the concept of euthanasia are shown in Tables 1 and 2. All respondents chose reasons from among the four listed in the questionnaire; no one added any additional reason.

Table 1.

Reasons for supporting the concept of euthanasia* n = 147

Table 2.

Reasons for opposing the concept of euthanasia* n = 65

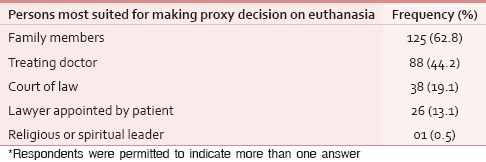

Most of the respondents (93.9%) felt that when necessary, a proxy decision could be taken for authorising euthanasia. Many of the respondents were of the opinion that either the family members or the treating doctor were most suited to make the final decision regarding euthanasia if the patient was not competent to do so [Table 3].

Table 3.

Opinion of respondents regarding the persons most suited for making proxy decision regarding euthanasia* n = 200

Being for or against euthanasia was not significantly associated with the designation of respondents as interns, postgraduates, or faculty (P = 0.70).

Two-thirds of the respondents (67.5%) had previously encountered terminally ill patients during the course of their practice. There was no association between having known a terminally ill patient and being for or against euthanasia (P = 0.71); 53.1% of doctors who had treated terminally ill patients felt that actually having known a terminally ill patient had no bearing on their outlook regarding euthanasia.

A significant association was observed between specialty and being in favor of euthanasia (P< 0.001). Doctors from medical specialties (78%), surgical specialties (75.9%), and pediatrics (68.4%) were more likely to support euthanasia when compared to doctors from the department of obstetrics and gynecology (45%).

DISCUSSION

This study suggests that the concept of euthanasia is acceptable to a large section of clinicians in this hospital in South India. However, we did not draw a distinction between active and passive euthanasia in this survey and it is not clear how exactly the respondents interpreted the term euthanasia. This is a limitation of this study and the results of the study need to be interpreted with this in mind.

Doctors may differ in how they define euthanasia.[5] The failure to distinguish between active and passive euthanasia might explain the large proportion of respondents in this study who favour euthanasia. Furthermore, while wide acceptance of euthanasia may be noted in response to a questionnaire as in this study, the support is likely to decrease when physicians actually encounter the situation in reality.[6]

It needs to be emphasised that this small sample from a single hospital is unlikely to be representative of the views of clinicians elsewhere in the country. Earlier studies from India have reported different results with most doctors who were surveyed strongly opposing euthanasia.[7,8] However, the phrasing of the questions may have affected the results.[9] A study in New Delhi found that a majority of physicians found withholding or withdrawal of treatment acceptable.[10] To get a more reliable indication of the views of the medical profession on this controversial issue, a larger study involving several centres across the country may be in order.

Just as attitudes towards death vary, it is clear that opinions on euthanasia also differ widely with country and cultural background [Table 4].[7,8,11–21] However, comparing results between countries can be difficult because the questionnaires and methods used often differ.

Table 4.

Physicians approving of euthanasia in various countries

No association was detected between age or gender and being in favor of the concept of euthanasia. Sociodemographic factors have been found to predict attitude towards euthanasia,[6] but some earlier studies did not find age and gender to be significantly associated with attitude towards euthanasia.[12,13,20]

Physicians who identified themselves to be Muslim or Christian were more likely to have a negative attitude towards euthanasia in this study. Physicians’ personal beliefs have been found to influence decision making at the end of life,[22] with Catholic or Jewish physicians being less willing to withdraw life support.[23] Similarly, in studies from Malaysia and Pakistan views on euthanasia are likely to have been governed by the religious beliefs of the respondents.[7,19,21] In this study, only religious affiliation was considered, though degree of religiosity has also been found to influence attitude towards euthanasia.[24–26]

Doctors from medical specialties, surgical specialties, or pediatrics were more likely to be proponents of euthanasia when compared to doctors from the department of obstetrics and gynecology. Studies elsewhere have also found doctors in certain specialties to be more in favor of euthanasia,[6] with palliative care specialists, oncologists, and geriatricians being less willing to actively hasten a patient's death.[27]

Just over half of those who had treated terminally ill patients felt that actually having known a terminally ill patient had no bearing on their attitude towards euthanasia; no association was detected between actually having known a terminally ill patient and being for or against euthanasia. These findings are at variance with results of previous studies which found that physicians with more experience of working with the dying were more opposed to euthanasia and physician assisted suicide.[20,27,28]

This study shows that the attitudes of a small sample of medical practitioners from an institution in South India seem more favourable to euthanasia than those reported from some other parts of India. However, it should be made clear that being in favour of euthanasia does not suggest willingness to actually perform euthanasia in the event that it is legalized.

With the increasing numbers of patients needing life support measures and palliative care, it is essential to obtain the views of a larger representative section of society as sooner or later the issue of legalizing euthanasia is likely to be raised.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We express our sincere thanks to Dr. Asha Kamath for her help with statistical analysis.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Definition of euthanasia. [Last accessed on 2010 Nov 25]. Available from: http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1O999-euthanasia.html.

- 2.Materstvedt LJ, Clark D, Ellershaw J, Førde R, Gravgaard AM, Müller-Busch HC, et al. Euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide: Aview from an EAPC Ethics Task Force. Palliat Med. 2003;17:97–101. doi: 10.1191/0269216303pm673oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garrard E, Wilkinson S. Passive euthanasia. J Med Ethics. 2005;31:64–8. doi: 10.1136/jme.2003.005777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Broeckaert B. Treatment decisions in advanced disease: A conceptual framework. Indian J Palliat Care. 2009;15:30–6. doi: 10.4103/0973-1075.53509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neil DA, Coady CA, Thompson J, Kuhse H. End-of-life decisions in medical practice: A survey of doctors in Victoria (Australia) J Med Ethics. 2007;33:721–5. doi: 10.1136/jme.2006.017137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Emanuel EJ. Euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:142–52. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.2.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abbas SQ, Abbas Z, Macaden S. Attitudes towards euthanasia and physician - assisted suicide among Pakistani and Indian doctors: A survey. Indian J Palliat Care. 2008;14:71–4. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dash SK. Medical ethics, duties and medical negligence awareness among the practitioners in a teaching medical college, hospital-A Survey. J Indian Acad Forensic Med. 2010;32:153–6. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hagelin J, Nilstun T, Hau J, Carlsson H-E. Surveys on attitudes towards legalisation of euthanasia: Importance of question phrasing. J Med Ethics. 2004;30:521–3. doi: 10.1136/jme.2002.002543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gielen J, Bhatnagar S, Mishra S, Chaturvedi AK, Gupta H, Rajvanshi A, et al. Can curative or life-sustaining treatment be withheld or withdrawn? The opinions and views of Indian palliative-care nurses and physicians. Med Health Care Philos. 2011;14:5–18. doi: 10.1007/s11019-010-9273-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Radulovic S, Mojsilovic S. Attitudes of oncologists, family doctors, medical students and lawyers to euthanasia. Support Care Cancer. 1998;6:410–5. doi: 10.1007/s005200050185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McGlade KJ, Slaney L, Bunting BP, Gallagher AG. Voluntary euthanasia in Northern Ireland: General practitioners’ beliefs, experiences, and actions. Br J Gen Pract. 2000;50:794–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Emanuel EJ, Fairclough D, Clarridge BC, Blum D, Bruera E, Penley WC, et al. Attitudes and practices of U.S. oncologists regarding euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:527–32. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-7-200010030-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Willems D L, Daniels E R, van der Wal G, van der Maas P J, Emanuel E J. Attitudes and practices concerning the end of life : A comparison between physicians from the United States and from the Netherlands. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:63–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Asai A, Ohnishi M, Nagata SK, Tanida N, Yamazaki Y. Doctors’ and nurses’ attitudes towards and experiences of voluntary euthanasia: survey of members of the Japanese Association of Palliative Medicine. JMed Ethics. 2001;27:324–30. doi: 10.1136/jme.27.5.324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yap HY, Joynt GM, Gomersall CD. Ethical attitudes of intensive care physicians in Hong Kong: Questionnaire survey. Hong Kong Med J. 2004;10:244–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mayda AS, Özkara E, Çorapçioğlu F. Attitudes of oncologists toward euthanasia in Turkey. Palliat Support Care. 2005;3:221–5. doi: 10.1017/s1478951505050340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vilela LP, Caramelli P. Knowledge of the definition of euthanasia: Study with doctors and caregivers of Alzheimer's disease patients. Rev AssocMed Bras. 2009;55:263–7. doi: 10.1590/s0104-42302009000300016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rathor MY, Rani MF, Akter SF, Azarisman SM. Religion and spirituality in specific clinical situations in medical practice; a cross-sectional comparative study between patients and doctors in a tertiary care hospital in Malaysia. Med JIslam World AcadSci. 2009;17:103–10. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Broeckaert B, Gielen J, Van Iersel T, Van den Branden S. The attitude of Flemish palliative care physicians to euthanasia and assisted suicide: An empirical study. Ethical Perspect. 2009;16:311–35. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Afzal MN, Latif R, Munir TA. Attitude of Pakistani doctors towards euthanasia and assisted suicide. Pak Armed Forces Med J. 2010;60:9–12. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hinkka H, Kosunen E, Metsänoja R, Lammi UK, Kellokumpu-Lehtinen P. Factors affecting physicians’ decisions to forgo life-sustaining treatments in terminal care. J Med Ethics. 2002;28:109–14. doi: 10.1136/jme.28.2.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Christakis NA, Asch DA. Physician characteristics associated with decisions to withdraw life support. Am J Public Health. 1995;85:367–72. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.3.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seale C. Legalisation of euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide: Survey of doctors’ attitudes. Palliat Med. 2009;23:205–12. doi: 10.1177/0269216308102041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCormack R, Clifford M, Conroy M. Attitudes of UK doctors towards euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide: A systematic literature review. Palliat Med. 2011 doi: 10.1177/0269216310397688. [In press] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Broeckaert B, Gielen J, Van Iersel T, Van den Branden S. Palliative care physicians’ religious / world view and attitude towards euthanasia: A quantitative study among Flemish palliative care physicians. Indian J Palliat Care. 2009;15:41–50. doi: 10.4103/0973-1075.53511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parker MH, Cartwright CM, Williams GM. Impact of specialty on attitudes of Australian medical practitioners to end-of-life decisions. Med J Aust. 2008;188:450–6. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2008.tb01714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee W, Price A, Rayner L, Hotopf M. Survey of doctors’ opinions of the legalisation of physician assisted suicide. BMC MedEthics. 2009;10:2. doi: 10.1186/1472-6939-10-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]