Abstract

Context:

Studies have documented that nurses and other health care professionals are inadequately prepared to care for patients in chronic pain. Several reasons have been identified including inadequacies in nursing education, absence of curriculum content related to pain management, and attitudes and beliefs related to chronic pain.

Aims:

The objective of this paper was to assess the chronic pain-related attitudes and beliefs among nursing professionals in order to evaluate the biomedical and behavioral dimensions of their perceptions on pain.

Settings and Design:

Cross-sectional survey of 363 nurses in a multispecialty hospital.

Materials and Methods:

The study utilized a self-report questionnaire – pain attitudes and beliefs scale (PABS) – which had 31 items (statements about pain) for each of which the person had to indicate the level at which he or she agreed or disagreed with each statement. Factor 1 score indicated a biomedical dimension while factor 2 score indicated a behavioral dimension to pain.

Statistical Analysis Used:

Comparisons across individual and professional variables for both dimensions were done using one-way ANOVA and correlations were done using the Karl–Pearson co-efficient using SPSS version 11.5 for Windows.

Results:

The overall factor 1 score was 52.95 ± 10.23 and factor 2 score was 20.93 ± 4.72 (P = 0.00). The female nurses had a higher behavioral dimension score (21.1 ± 4.81) than their male counterparts (19.55 ± 3.67) which was significant at P < 0.05 level.

Conclusions:

Nurses had a greater orientation toward the biomedical dimension of chronic pain than the behavioral dimension. This difference was more pronounced in female nurses and those nurses who reported very “good” general health had higher behavioral dimension scores than those who had good general health. The study findings have important curricular implications for nurses and practical implications in palliative care.

Keywords: Nursing education, Pain assessment, Professional behavior, Professional psychology, Psychosocial issues

INTRODUCTION

Health care professionals’ knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and experiences determine not only their procedure but also their behavior during the evaluation and treatment of patients with chronic pain.[1] Pain is the common complaint and is often a topic of discussion both between patients and their caregivers, and between physicians and other palliative care team members.[2] After physicians, the nurses are the most valuable palliative care team members who address the physical, functional, social, and spiritual dimensions of care.[3] Five pain management activities performed by nurse practitioners were identified, including assessing pain, prescribing pain medications, monitoring pain levels and side-effects of pain medications, consulting and advocating for staff and patients, and leading and educating staff related to pain management.[4] Studies have also documented that nurses and other health care professionals are inadequately prepared to care for patients in chronic pain. Several reasons have been identified including inadequacies in nursing and medical education, absence of curriculum content related to pain management, and faculty attitudes and beliefs related to chronic pain.[5]

During a patient's stay in a ward, nurses hold a great deal of responsibility for pain management, especially when analgesics are prescribed on an “as needed” basis for patients with chronic pain. Despite the availability of effective analgesics and new technologies for drug administration, studies continue to demonstrate suboptimal pain management.[6] Accurate pain assessment is vital for good medical care, and yet the literature indicates that nurses often provide inaccurate and biased estimates of their patients’ pain.[7]

The knowledge and understanding about chronic pain had undergone a paradigm shift from a biomedical dimension to a behavioral dimension.[8–10] In other words, an anatomical or pathological understanding is now replaced with biopsychosocial perspective for pain.[11] One such recent biopsychosocial explanation of pain is the mechanism-based classification, used by physical therapists’ management in palliative care.[12] Psychosocial issues among patients are often recognized in the field of palliative care.[13] Pain is not only reported as a common complaint from patients, but also is a common experience among human beings in general.[14]

Previous studies evaluated nurses’ attitudes towards pain control,[15] palliative sedation,[15,16] life-sustaining treatment,[17] death,[18] end-of-life referrals,[19] caring for clients with sexual health concerns,[20,21] caring for people with HIV/AIDS,[22] and caring for dying.[18,23,24]

Though there were studies that previously examined nurses’ attitudes towards pain, many were on questionnaire development,[25–27] level of education,[28–31] practice patterns,[32] and type of work setting.[28,33] None of the studies appropriately examined the two dimensions, biomedical and behavioral, which determine the clinical approach of the nurses in pain and palliative care. A nurse who has a predominantly biomedical orientation toward pain may be more inclined not to give frequent analgesics in order to avoid patient addiction while a nurse with a behavioral orientation may provide prescribed analgesics to the patient frequently whenever indicated so that the patient may deserve to have a better quality of life. While a “biomedical” nurse may be interested in what the patient “does,” a “behavioral” nurse may be interested in what the patient "feels." Integrating the behavioral dimension in understanding of pain is essentially warranted in a situation such as palliative care.

Although effective means for chronic pain management have long been available, cancer pain remains widely undertreated.[34] Balfour[35] found that nurses did not always administer all the analgesia prescribed to patients, even though patients reported suffering pain. Surveys of medical personnel have revealed knowledge deficits and attitudinal barriers to chronic pain management, but have not determined why such attitudes persist and how they may be addressed in medical and nursing curricula.[36] The role of nurses in palliative care settings had been understood in extensive proportion, and invariably their attitudes and beliefs about chronic pain in terms of biomedical and/or behavioral dimensions would have a direct impact on their communication both with patients/ caregivers and with physicians/other team members. Knowing the present levels of professionals’ attitudes and beliefs facilitate appropriate training programs[37–40] to address identified deficits and thereby to improve the quality of provided care. The objective of this paper was to assess the chronic pain-related attitudes and beliefs among nursing professionals in order to evaluate the biomedical and behavioral dimensions of their perceptions on chronic pain.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was conducted in a multispecialty tertiary care hospital, where the participants included those who attended a continuing professional development program exclusively for qualified staff nurses with a minimum of Baccalaureate degree in nursing. Study's ethical approval was obtained from the institutional ethics committee and all participants were required to provide their written informed consent prior to their participation. Consented participants were then given the survey questionnaire.

The study utilized a self-report questionnaire which was modified from its original version, the pain attitudes and beliefs scale (PABS) developed and validated earlier by Ostelo et al.,[41] for measuring health care providers’ attitudes and beliefs toward chronic low back pain.[42] The term “chronic low back pain” was replaced by “chronic pain” in all the items of the questionnaire. The scale had 31 items (statements about pain) for each of which the person had to indicate the level on which he or she agreed or disagreed with each statement: 1 = “totally disagree,” 2 = “largely disagree,” 3 = “disagree to some extent,” 4 = “agree to some extent,” 5 = “largely agree,” and 6 = “totally agree.” To calculate the score of factor 1, the scores of items 4, 5, 9, 10, 13, 14, 20, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 30, and 31 were added. For factor 2, the scores of items 3, 6, 7, 11, 12, and 27 were added. For factor 1, the range was from 14 through 84, and from 6 through 36 for factor 2.

The received questionnaires were then screened for their suitability of responses to get the final number of included participants’ questionnaires. Thus, we arrived at the response rate for our survey.

Comparisons across individual and professional variables for both dimensions were done using one-way ANOVA (post-hoc analysis using the Bonferonni test) and correlations were done using the Karl–Pearson co-efficient using SPSS version 11.5 for Windows (SPSS Inc., IL, USA).

RESULTS

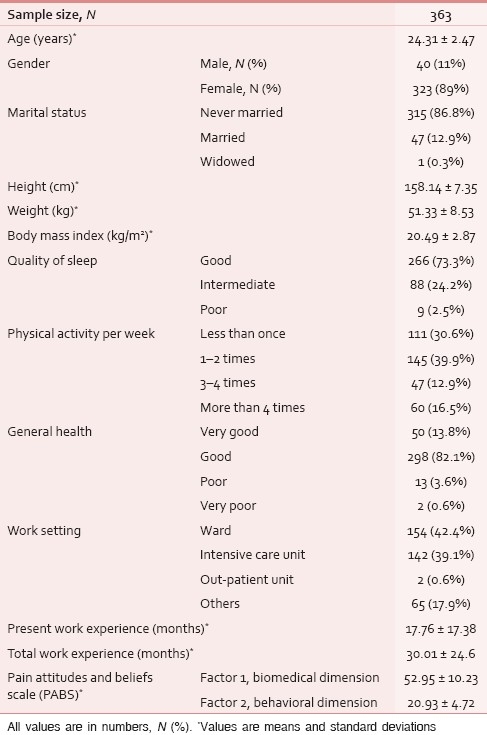

Out of total 392 questionnaires distributed and collected, 363 valid questionnaires were included for analysis, with a response rate of 92.6%. The overall descriptive data of the study participants are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Overall descriptive data of study participants

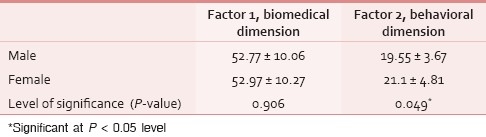

Comparison of PABS dimensions between genders

The female nurses had a higher behavioral dimension score than their male counterparts which was significant at P < 0.05 level. The biomedical dimension was not significantly different between genders [Table 2 and Figure 1].

Table 2.

Comparison of pain attitudes and beliefs scale dimensions between genders

Figure 1.

Comparison of pain attitudes and beliefs scale (PABS) dimensions between genders

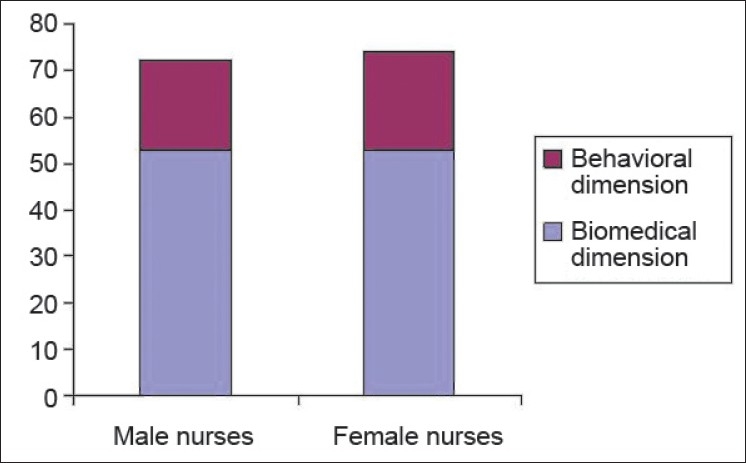

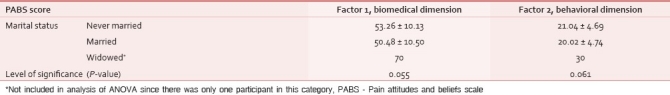

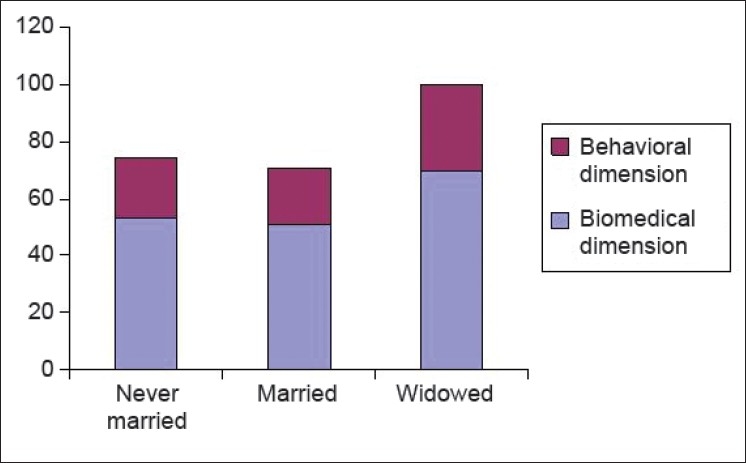

Comparison of PABS dimensions between marital statuses categories

Both the dimensions did not differ significantly between the three marital statuses among the nurses [Table 3 and Figure 2].

Table 3.

Comparison of pain attitudes and beliefs scale dimensions between marital status categories

Figure 2.

Comparison of pain attitudes and beliefs scale dimensions between marital status categories

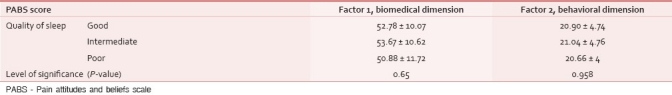

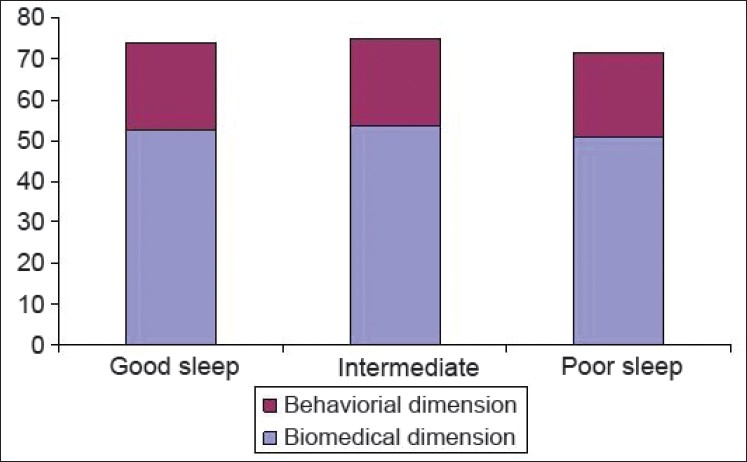

Comparison of PABS dimensions between qualities of sleep categories

Both the dimensions did not differ significantly between the three qualities of sleep categories among the nurses [Table 4 and Figure 3].

Table 4.

Comparison of pain attitudes and beliefs scale dimensions between qualities of sleep categories

Figure 3.

Comparison of pain attitudes and beliefs scale dimensions between qualities of sleep categories

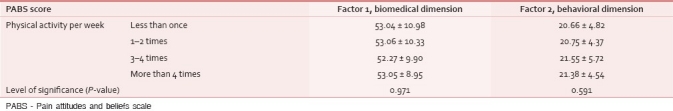

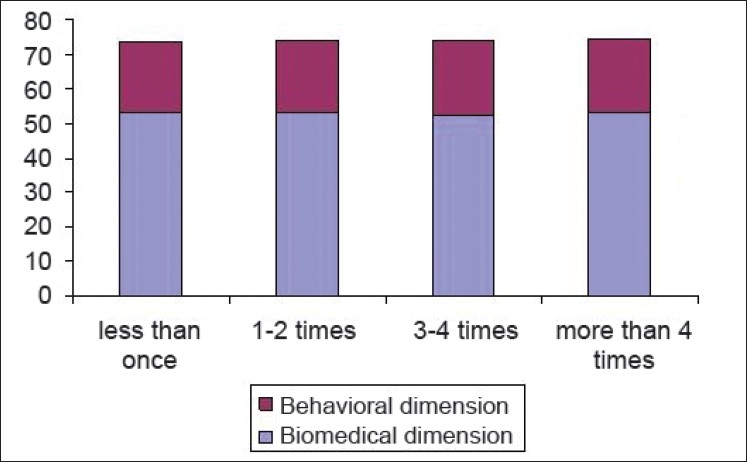

Comparison of PABS dimensions between physical activities categories

Both the dimensions did not differ significantly between the three physical activity categories among the nurses [Table 5 and Figure 4].

Table 5.

Comparison of pain attitudes and beliefs scale dimensions between physical activity categories

Figure 4.

Comparison of pain attitudes and beliefs scale dimensions between physical activity categories

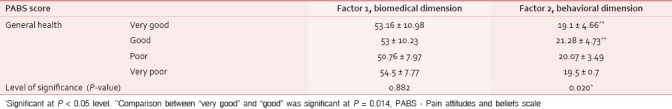

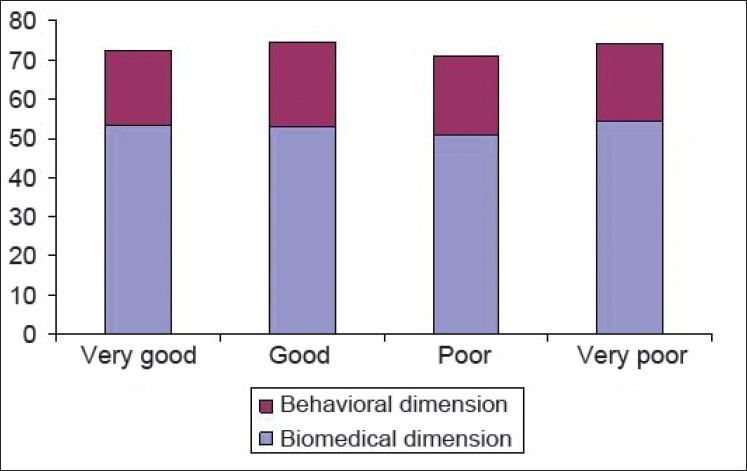

Comparison of PABS dimensions between general health categories

A statistically significant overall comparison was found for behavioral dimension scores between the three health categories with the post-hoc comparison being significant between “very good” and “good” health categories [Table 6 and Figure 5].

Table 6.

Comparison of pain attitudes and beliefs scale dimensions between general health categories

Figure 5.

Comparison of pain attitudes and beliefs scale dimensions between general health categories

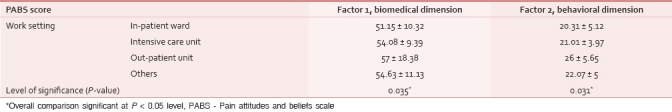

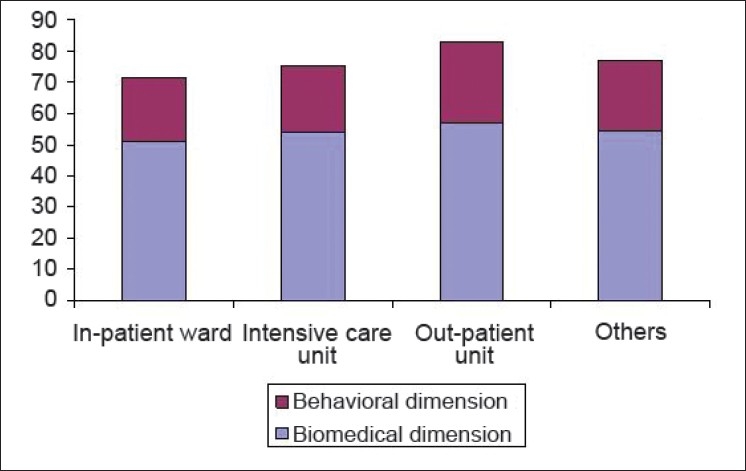

Comparison of PABS dimensions between types of work settings

A statistically significant overall comparison was found both for biomedical and behavioral dimension scores between the four work setting categories with the post-hoc comparison being not significant between any categories [Table 7 and Figure 6].

Table 7.

Comparison of pain attitudes and beliefs scale dimensions between types of work settings

Figure 6.

Comparison of pain attitudes and beliefs scale dimensions between types of work settings

Secondary analysis

Age (r = –0.033), body height (r = 0.004), body weight (r = –0.020), BMI (r = –0.023), work experience in the present job (r = –0.058), and total work experience (r = –0.004) were not significantly associated with the factor 1 biomedical dimension subscore of PABS.

Age (r = –0.001), body height (r = 0.024), body weight (r = –0.033), BMI (r = –0.046), work experience in the present job (r = –0.088), and total work experience (r = –0.008) were not significantly associated with the factor 2 behavioral dimension subscore of PABS.

The factor 1 subscore had a moderate positive correlation (r = 0.445) than the factor 2 subscore of PABS which was statistically significant at P < 0.01. In all analyses, the biomedical dimension score was significantly greater than the behavioral dimension score for all categories and subcategories.

DISCUSSION

Nursing pain assessments are influenced by the length of available tools, patient characteristics, patient pathology, concern about addictive behavior, and characteristics of the nurse.[43] Pain by definition is a multifactorial phenomenon for which biomedical factors interact with a web of psychosocial and behavioral factors. Behavioral medicine approaches for pain generally address specific cognitive and behavioral factors relevant to chronic pain, thereby aiming to modify the overall pain experience and help restore functioning and quality of life in pain patients. Behavioral medicine focuses on patients’ motivation to comply with a rehabilitative regimen, particularly those with chronic, disabling pain. Since patients’ own commitment and active participation in a therapeutic program are critical for the successful rehabilitation, the role that behavioral medicine can play in pain and palliative care is significant.[44]

This study included bio-psycho-social factors related to nursing staff such as age, gender, height, weight, and BMI; quality of sleep and general health; and physical activity and work setting. We considered the above-mentioned individual-related variables such as age, height, weight, and BMI with respect to chronic pain-related attitudes and beliefs since these anthropometric factors were shown to be related to the development of pain.[45] Previous studies reported biopsychosocial risk factors[46–48] for the development of chronic pain among nurses and they found a significant influence of age and gender on nurses’ attitudes toward not only pain assessment and management but also on pain[49] and patients’ pain identities per se.[50] Other psychosocial factors, both work related[51] and health related,[52] were studied as influencing heath behaviors in the development of chronic pain among nurses. Personal experience in chronic pain would influence attitudes and beliefs to a greater extent than knowledge acquired through formal training.

Inadequacies in the pain management process may not be tied to myths and biases originating from general attitudes and beliefs, but may reflect inadequate pain knowledge.[53] Future studies may assess such relationships between knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors of nurses in real-life palliative care situations. The study findings are of utmost significance since individual attitudes and beliefs largely determine the interindividual and interdisciplinary communication in a multidisciplinary care framework for pain and palliative care.[54] Attitudes together with subjective norms and perceived control influence nurses’ intention to perform comprehensive pain assessments.[55]

Patients who do not report pain and health care providers who fail to assess for pain are major barriers to the relief of chronic pain. Using pain as the fifth vital sign and being knowledgeable about pain assessment and management can help nurses and other health care providers overcome many of the barriers to successful pain control. A successful pain control plan includes establishing the pain diagnosis, treating the cause of the chronic pain when possible, optimizing analgesic use, implementing nonpharmacological interventions to maximize physical and psychological comfort and function, and referring the patient for invasive pain management options when indicated.[56]

The findings also suggest that a further study is needed concerning the relationship between personal beliefs and experiences and the assessment and management of chronic pain. Membership in professional organizations appears to be associated with comprehensive approaches to the assessment and management of pain and should be assessed in further research.[43]

CONCLUSION

Nurses had a greater orientation toward the biomedical dimension in chronic pain than the behavioral dimension. This difference was more pronounced in female nurses and those nurses who reported “very good” general health had higher behavioral dimension scores than those who had “good” general health. The study findings have important curricular implications for nurses and practical implications in palliative care.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors wish to thank nurses who participated in the study for taking out their valuable time and sharing their views and opinions in the survey.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lovering S. Cultural attitudes and beliefs about pain. J Transcult Nurs. 2006;17:389–95. doi: 10.1177/1043659606291546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirk TW. Managing pain, managing ethics. Pain Manag Nurs. 2007;8:25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Egan KA, Abbott P. Interdisciplinary team training- preparing new employees for the specialty of hospice and palliative care. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2002;4:161–71. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaasalainen S, Martin-Misener R, Carter N, Dicenso A, Donald F, Baxter P. The nurse practitioner role in pain management in long-term care. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66:542–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferrell BR, McGuire DB, Donovan MI. Knowledge and beliefs regarding pain in a sample of nursing faculty. J Prof Nurs. 1993;9:79–88. doi: 10.1016/8755-7223(93)90023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schafheutle EI, Cantrill JA, Noyce PR. Why is pain management suboptimal on surgical wards? J Adv Nurs. 2001;33:728–37. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harrison A. Assessing patients’ pain: Identifying reasons for error. J Adv Nurs. 1991;16:1018–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1991.tb03361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jamison RN, Rudy TE, Penzien DB, Mosley TH., Jr Cognitive-behavioral classifications of chronic pain: replication and extension of empirically derived patient profiles. Pain. 1994;57:277–92. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)90003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lipsky PE, Buckland J. Pain by name, pain by nature. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010;6:179–80. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keefe FJ, Somers TJ. Psychological approaches to understanding and treating arthritis pain. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010;6:210–6. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Syrjala KL, Chapko ME. Evidence for a biopsychosocial model of cancer treatment-related pain. Pain. 1995;61:69–79. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)00153-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumar SP, Saha S. Mechanism-based classification of pain for physical therapy management in palliative care: A Clinical Commentary. Indian J Palliat Care. 2011;17:80–6. doi: 10.4103/0973-1075.78458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Onyeka TC. Psychosocial issues in palliative care- a review of five cases. Indian J Palliat Care. 2010;16:123–8. doi: 10.4103/0973-1075.73642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schiefenhövel W. Perception, expression, and social function of pain: A human ethological view. Sci Context. 1995;8:1–46. doi: 10.1017/s0269889700001885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gielen J, Gupta H, Rajvanshi A, Bhatnagar S, Mishra S, Chaturvedi AK, et al. The attitudes of Indian palliative-care nurses and physicians to pain control and palliative sedation. Indian J Palliat Care. 2011;17:33–41. doi: 10.4103/0973-1075.78447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brinkkemper T, Klinkenberg M, Deliens L, Eliel M, Rietjens JA, Zuurmond WW, et al. Palliative sedation at home in the Netherlands: A nationwide survey among nurses. J Adv Nurs. 2011;67:1719–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gielen J, Bhatnagar S, Mishra S, Chaturvedi AK, Gupta H, Rajvanshi A, et al. Can curative or life-sustaining treatment be withheld or withdrawn. The opinions and views of Indian palliative-care nurses and physicians? Med Health Care Philos. 2011;14:5–18. doi: 10.1007/s11019-010-9273-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lange M, Thom B, Kline NE. Assessing nurses’ attitudes toward death and caring for dying patients in a comprehensive cancer center. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2008;35:955–9. doi: 10.1188/08.ONF.955-959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rolland RA, Kalman M. Nurses’ attitudes about end-of-life referrals. J N Y State Nurses Assoc. 2007;38:10–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Magnan MA, Norris DM. Nursing students’ perceptions of barriers to addressing patient sexuality concerns. J Nurs Educ. 2008;47:260–8. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20080601-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kong SK, Wu LH, Loke AY. Nursing students’ knowledge, attitude and readiness to work for clients with sexual health concerns. J Clin Nurs. 2009;18:2372–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pickles D, King L, Belan I. Attitudes of nursing students towards caring for people with HIV/AIDS: Thematic literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65:2262–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iranmanesh S, Dargahi H, Abbaszadeh A. Attitudes of Iranian nurses toward caring for dying patients. Palliat Support Care. 2008;6:363–9. doi: 10.1017/S1478951508000588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iranmanesh S, Axelsson K, Häggström T, Sävenstedt S. Caring for dying people: Attitudes among Iranian and Swedish nursing students. Indian J Palliat Care. 2010;16:147–53. doi: 10.4103/0973-1075.73643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manworren RC. Development and testing of the Pediatric Nurses’ Knowledge and Attitudes Survey Regarding Pain. Pediatr Nurs. 2001;27:151–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tafas CA, Patiraki E, McDonald DD, Lemonidou C. Testing an instrument measuring Greek nurses’ knowledge and attitudes regarding pain. Cancer Nurs. 2002;25:8–14. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200202000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rieman MT, Gordon M, Marvin JM. Pediatric nurses’ knowledge and attitudes survey regarding pain: A competency tool modification. Pediatr Nurs. 2007;33:303–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manworren RC. Pediatric nurses’ knowledge and attitudes survey regarding pain. Pediatr Nurs. 2000;26:610–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greenberger C, Reches H, Riba S. Levels and predictors of knowledge and attitudes regarding pain among Israeli baccalaureate nursing students and nurses pursuing specialty certification. Int J Nurs Educ Scholarsh. 2006;3:8. doi: 10.2202/1548-923X.1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Plaisance L, Logan C. Nursing students’ knowledge and attitudes regarding pain. Pain Manag Nurs. 2006;7:167–75. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lasch K, Greenhill A, Wilkes G, Carr D, Lee M, Blanchard R. Why study pain.A qualitative analysis of medical and nursing faculty and students’ knowledge of and attitudes to cancer pain management? J Palliat Med. 2002;5:57–71. doi: 10.1089/10966210252785024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mrozek JE, Werner JS. Nurses’ attitudes toward pain, pain assessment and pain management practices in long-term care facilities. Pain Manag Nurs. 2001;2:154–62. doi: 10.1053/jpmn.2001.26530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hunt K. Perceptions of patients’ pain: A study assessing nurses’ attitudes. Nurs Stand. 1995;10:32–5. doi: 10.7748/ns.10.4.32.s30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deandrea S, Montanari M, Moja L, Apolone G. Prevalence of undertreatment in cancer pain.A review of published literature. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:1985–91. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Balfour SE. Will I be in pain. Patients’ and nurses’ attitudes to pain after abdominal surgery? Prof Nurse. 1989;5:28–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lasch K, Greenhill A, Wilkes G, Carr D, Lee M, Blanchard R. Wht study pain? A qualitative analysis of medical and nursing faculty students’ knowledge of and attitudes to cancer pain management. J Palliat Med. 2002;5:57–71. doi: 10.1089/10966210252785024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mallory JL. The impact of a palliative care educational component on attitudes toward care of the dying in undergraduate nursing students. J Prof Nurs. 2003;19:305–12. doi: 10.1016/s8755-7223(03)00094-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kwekkeboom KL, Vahl C, Eland J. Impact of a volunteer companion program on nursing students’ knowledge and concerns related to palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:90–9. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barrere CC, Durkin A, LaCoursiere S. The influence of end-of-life education on attitudes of nursing students. Int J Nurs Educ Scholarsh. 2008;5:11. doi: 10.2202/1548-923X.1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kumar SP, Jim A, Sisodia V. Effects of palliative care training program on knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and experiences among student physiotherapists: A preliminary Quasi-experimental study. Indian J Palliat Care. 2011;17:47–53. doi: 10.4103/0973-1075.78449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ostelo RW, Stomp-van den Berg SG, Vlaeyen JW, Wolters PM, de Vet HC. Health care provider's attitudes and beliefs towards chronic low back pain: The development of a questionnaire. Man Ther. 2003;8:14–22. doi: 10.1016/s1356-689x(03)00013-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bishop A, Thomas E, Foster NE. Health care practitioners’ attitudes and beliefs about low back pain: a systematic search and critical review of available measurement tools. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2007;132:91–101. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dalton JA. Nurses’ perceptions of their pain assessment skills, pain management practices, and attitudes toward pain. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1989;16:225–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Okifuji A, Ackerlind S. Behavioral medicine approaches to pain. Med Clin North Am. 2007;91:45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kumar SP. Are you at risk for musculoskeletal pain.An evidence-informed review: Part-1: Anthropometric factors? Physiotimes. 2010;2:4–9. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mitchell T, O’Sullivan PB, Smith A, Burnett AF, Straker L, Thornton J, et al. Biopsychosocial factors are associated with low back pain in female nursing students: A cross-sectional study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46:678–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lorusso A, Bruno S, L’Abbate N. A review of low back pain and musculoskeletal disorders among Italian nursing personnel. Ind Health. 2007;45:637–44. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.45.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Feng CK, Chen ML, Mao IF. Prevalence of and risk factors for different measures of low back pain among female nursing aides in Taiwanese nursing homes. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2007;8:52. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-8-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bernardes SF, Lima ML. Being less of a man or less of a woman: Perceptions of chronic pain patients’ gender identities. Eur J Pain. 2010;14:194–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mrozek JE, Werner JS. Nurses’ attitudes toward pain, pain assessment, and pain management practices in long-term care facilities. Pain Manag Nurs. 2001;2:154–62. doi: 10.1053/jpmn.2001.26530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cheng Y, Kawachi I, Coakley EH, Schwartz J, Colditz G. Association between psychosocial work characteristics and health functioning in American women: Prospective study. BMJ. 2000;320:1432–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7247.1432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Michael YL, Colditz GA, Coakley E, Kawachi I. Health behaviors, social networks, and healthy aging: Cross-sectional evidence from the Nurses’ Health Study. Qual Life Res. 1999;8:711–22. doi: 10.1023/a:1008949428041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wilson B. Nurses’ knowledge of pain. J Clin Nurs. 2007;16:1012–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.01692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brown CA, Richardson C. Nurses’ in the multi-professional pain team: A study of attitudes, beliefs and treatment endorsements. Eur J Pain. 2006;10:13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nash R, Edwards H, Nebauer M. Effect of attitudes, subjective norms and perceived control on nurses’ intention to assess patients’ pain. J Adv Nurs. 1993;18:941–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1993.18060941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lynch M. Pain as the fifth vital sign. J Intraven Nurs. 2001;24:85–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]