Abstract

Background:

Acanthosis nigricans (AN) is a dermatosis characterized by thickened, hyperpigmented plaques, typically on the intertriginous surfaces and neck. Common in some populations, its prevalence depends on race. Clinicians should recognize AN; it heralds disorders ranging from endocrinologic disturbances to malignancy. In this review, we discuss the pathogenesis of AN and its clinical implications and management.

Materials and Methods:

We selected 30 patients for the study. Diagnosis of associated disorders was established by history, physical examination, body mass index (BMI), hormone measurements by radioimmunoassays of thyroidnfunction tests, free testosterone, 17 (OH) progesterone, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS), cortisol, gonadotropins, prolactin, immunoreactive insulin, and C-peptide levels.

Results and Discussion:

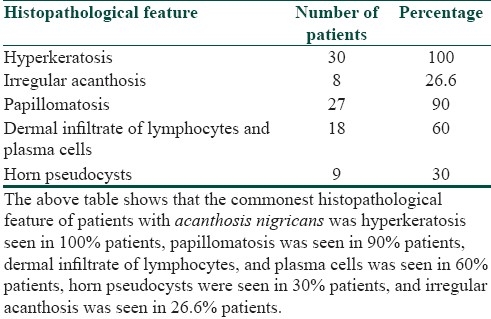

In our study, the flexural involvement (flexures of groins, knees and elbows) was seen in 40% patients, lip involvement was seen in 6.6% patients, and dorsal involvement was seen in 3.3% patients each. Increased serum testosterone levels were seen in 13.3% patients and increased DHEAS levels were seen in 20% patients. Regarding the types of AN, obesity induced AN or pseudo-AN was seen 70% patients, syndromic AN was seen in 23.35% patients and malignant AN was seen in 6.6% patients. The commonest histopathological feature of patients with AN was hyperkeratosis, seen in 100% patients, papillomatosis was seen in 90% patients, dermal infiltrate of lymphocytes and plasma cells was seen in 60% patients, horn pseudocysts were seen in 30% patients, and irregular acanthosis was seen in 26.6% patients.

Keywords: Acanthosis nigricans, endocrinal, familial, hyperpigmented, malignant, obesity, polycystic ovarian disease, syndrome

Introduction

Acanthosis nigricans (AN) is a dermatosis characterized by velvety, papillomatous, brownish-black, hyperkeratotic plaques, typically on the intertriginous surfaces and neck.[1,2] Although AN is associated with malignancy, the recognition of its more common connection to obesity and insulin resistance allows for diagnosis of related disorders including type 2 diabetes, the metabolic syndrome, and polycystic ovary syndrome. Early recognition of these conditions is essential for prevention of disease progression. The exact incidence of AN is unknown. In an unselected population of 1412 children, the changes of AN were present in 7.1%.[3] Obesity is closely associated with AN and more than half the adults who weigh greater than 200% of their ideal body weight have lesions consistent with AN. The malignant form of AN is far less common, and in one study, only 2 of 12,000 patients with cancer had signs of AN. The most frequent associations were with adenocarcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract (70-90%), particularly gastric cancer (55-61% of malignant AN cases).[4] Approximately, 61.3% of cases are diagnosed simultaneously with the cancer manifestation, while 17.6% of malignant AN cases predate the diagnosis of malignancy. AN is much more common in people with darker skin pigmentation. The prevalence in whites is less than 1%. In Latinos, the prevalence in one study was 5.5%, and in African Americans, the prevalence is higher, at 13.3%.[5]

Clinically, the neck is the most commonly affected area in children. Ninety-nine percent of children with AN have neck involvement compared to 73% with axillary involvement. AN may also affect eyelids, lips, vulva, mucosal surfaces, dorsal hands, and flexural areas in the groin, knees and elbows.[6,7] While usually asymptomatic, AN is occasionally pruritic. Histopathology reveals a thickened stratum corneum with minimal involvement of the dermis except for thickened and elongated dermal projections. Despite the term “acanthosis,” the actual amount of acanthosis or thickening of the stratum spinosum is variable and typically mild. The dark color of AN is likely due to hyperkeratosis rather than a mild increase in melanin pigmentation. A subtle infiltrate composed of lymphocytes, plasma cells, or neutrophils may be present, as well as horn pseudocyst formation. Tissue staining with colloidal iron often shows infiltration of the papillary dermis with glycosaminoglycans such as hyaluronic acid, particularly in patients with gonadal disease such as polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS). AN is linked to variety of syndromes. Most are associated with insulin resistance or fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) mutations. AN may also appear as an adverse effect of several medications that promote hyperinsulinemia such as glucocorticoids, niacin, insulin, oral contraceptives, and protease inhibitors.[8]

Aims

To study the epidemiology and clinical features of 30 patients with AN.

To study the histopathological characteristics of 30 patients with AN

Materials and Methods

We selected 30 patients for the study. Prior approval of hospital ethical committee was taken before the start of the study. The weight and the height of the patients were measured. All patients had AN with velvety, hyperpigmented thickening of skin over the nape of the neck, with or without involvement of axillae and other flexure areas. Papillomatous formation was present in most cases. No eyelids, conjunctiva or oral cavity involvement with AN was found in any of these patients. Diagnosis of associated disorders was established by history, physical examination, body mass index (BMI), hormone measurements by radioimmunoassays of thyroid function tests, free testosterone, 17 (OH) progesterone, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS), cortisol, gonadotropins, prolactin, immunoreactive insulin, and C-peptide levels. Further, work-up of PCOS included ultrasonography of ovaries. Obesity was diagnosed when BMI exceeded 27 kg/m2 . In this series, BMI of obese patients ranged from 27-51 kg/m2 . With variations of phenotypic expressions of various components of the PCOS, the presence of clinically significant number of the following criteria was considered in diagnosing PCOS 1) history of menstrual irregularities and/or anovulation; 2) hirsutism and/or temporal balding, oily skin and acne; 3) elevated serum-free testosterone and/or elevated luteinizing hormone/follicle-stimulating hormone (LH/FSH) ratio; and 4) ultrasonographic finding of polycystic ovaries.

For patients with adult onset of AN, a basic workup for underlying malignancy was performed. All patients were screened for diabetes with a glycosylated hemoglobin level or glucose tolerance test. The patients were screened for insulin resistance by measuring plasma insulin level which was high in those with insulin resistance. Plasma glucose was estimated by glucose oxidase method and insulin levels were estimated by radioimmunoassay (RIA) (double antibody technique). For patients with adult onset of AN, a basic workup for underlying malignancy was performed. All subjects underwent a detailed physical examination including anthropometry (height, weight, waist and hip circumference). From these data, BMI, waist/hip ratio (WHR), and lean body mass (LBM) were calculated. Four mm punch biopsies of the neck or axillary lesion were performed under local anesthesia with precautions. The biopsy was fixed in formalin, sectioned and stained with H and E.

Results

The results were tabulated and the data was analyzed.

Discussion

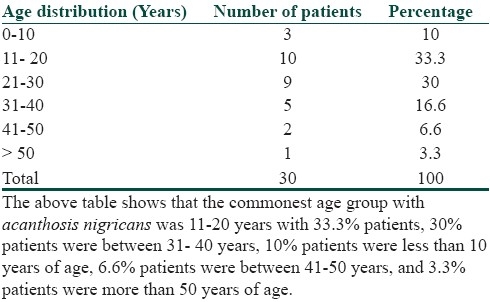

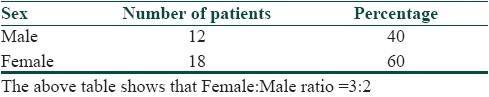

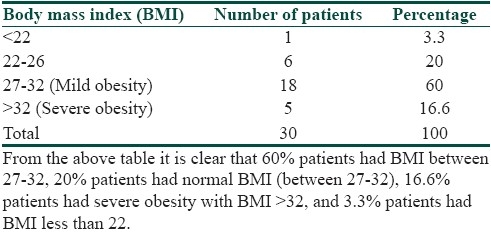

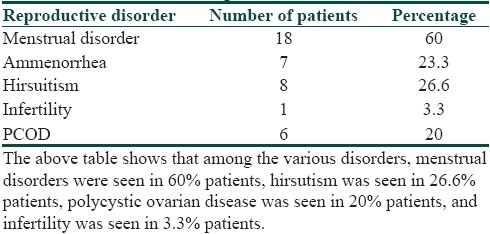

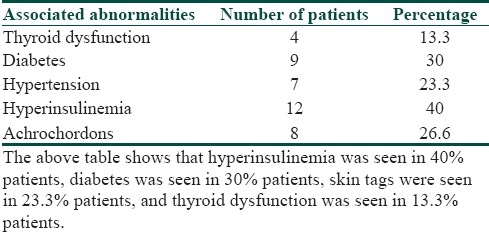

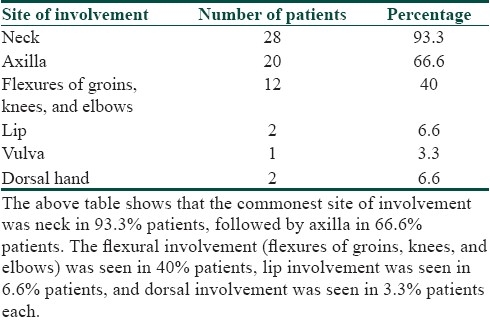

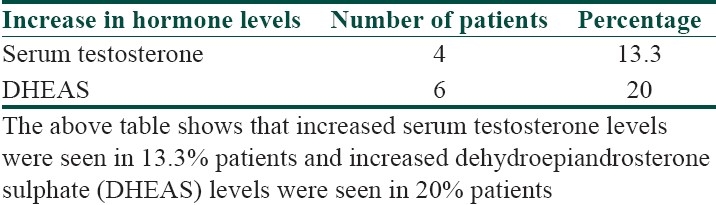

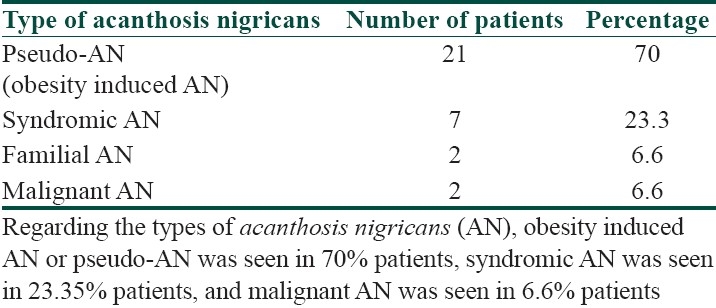

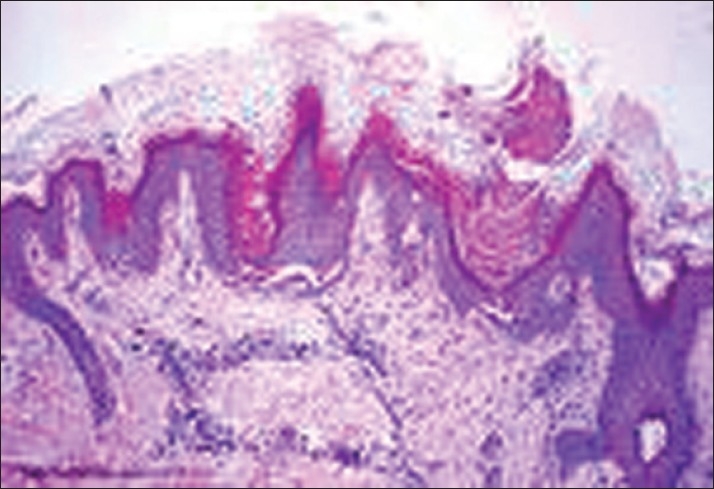

It was seen that the commonest age group with AN was 11-20 years with 33.3% patients, 30% patients were between 31- 40 years, 10% patients were less than 10 years of age, 6.6% patients were between 41-50 years, and 3.3% patients were more than 50 years of age [Table 1]. Females outnumbered males [Table 2] and female: male ratio =3: 2. In our study, 60% patients had BMI between 27-32, 20% patients had normal BMI (between 27-32), 16.6% patients had severe obesity with BMI>32, and 3.3% patients had BMI less than 22 [Table 3]. Among the various disorders, menstrual disorders [Table 4] were seen in 60% patients, hirsutism was seen in 26.6% patients, polycystic ovarian disease was seen in 20% patients, and infertility was seen in 3.3% patients. Hyperinsulinemia was seen in 40% patients, diabetes was seen in 30% patients, skin tags were seen in 23.3% patients, and thyroid dysfunction was seen in 13.3% patients [Table 5]. The commonest site of involvement [Table 6] was neck in 93.3% patients, followed by axilla in 66.6% patients [Figure 1]. The flexural involvement (flexures of groins, knees, and elbows) was seen in 40% patients, lip involvement was seen in 6.6% patients, and dorsal involvement was seen in 3.3% patients each. Increased serum testosterone levels were seen in 13.3% patients and increased dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate (DHEAS) levels were seen in 20% patients [Table 7]. Regarding the types of AN, obesity induced AN or pseudo-AN was seen in 70% patients, syndromic AN was seen in 23.35% patients, and malignant AN was seen in 6.6% patients [Table 8]. The commonest histopathological feature of patients with AN [Table 9] was hyperkeratosis, seen in 100% patients, papillomatosis was seen in 90% patients, dermal infiltrate of lymphocytes, and plasma cells was seen in 60% patients, horn pseudocysts were seen in 30% patients, and irregular acanthosis was seen in 26.6% patients [Figure 2].

Table 1.

Age distribution of patients of acanthosis nigricans

Table 2.

Sex distribution of patients

Table 3.

Body mass index (BMI) in patients of acanthosis nigricans

Table 4.

Reproductive disorders in patients of acanthosis nigricans

Table 5.

Associated abnormalities in patients of acanthosis nigricans

Table 6.

Sites of involvement of patients of acanthosis nigricans

Figure 1.

Figure showing pseudo-AN in the axilla

Table 7.

Hormonal levels in patients of acanthosis nigricans

Table 8.

Types of acanthosis nigricans

Table 9.

Histopathology of patients of acanthosis nigricans

Figure 2.

Photomicrograph showing papillomatosis and horn pseudocysts (H and E, stain 100×)

The definitive cause of AN has not yet been ascertained, although several possibilities have been suggested. Eight types of AN have been described. Obesity-associated AN, once labeled pseudo-AN, is the most common type of AN.[9,10] Lesions may appear at any age, but are more common in adulthood. The dermatosis is weight dependent and lesions may completely regress with weight reduction. Insulin resistance is often present in these patients; however, it is not universal. Syndromic AN is the name given to AN that is associated with a syndrome. In addition to the widely recognized association of AN with insulin resistance, AN has been associated with numerous syndromes. The type A syndrome and type B syndrome are special examples. The type A syndrome also is termed the hyperandrogenemia, insulin resistance, and AN syndrome (HAIR-AN syndrome).[11] This syndrome is often familial, affecting primarily young women (especially black women). It is associated with polycystic ovaries or signs of virilization (e.g., hirsutism, clitoral hypertrophy). High plasma testosterone levels are common. The lesions of AN may arise during infancy and progress rapidly during puberty. The type B syndrome generally occurs in women who have uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, ovarian hyperandrogenism, or an autoimmune disease such as systemic lupus erythematosus, scleroderma, Sjögren syndrome, or Hashimoto thyroiditis. Circulating antibodies to the insulin receptor may be present. In these patients, the lesions of AN are of varying severity.

Acral AN (acral acanthotic anomaly) occurs in patients who are in otherwise good health. Acral AN is most common in dark-skinned individuals, especially those of African American descent. The hyperkeratotic velvety lesions are most prominent over the dorsal aspects of the hands and feet.[12] Unilateral AN, sometimes referred to as nevoid AN, is believed to be inherited as an autosomal dominant trait. Lesions are unilateral in distribution and may become evident during infancy, childhood, or adulthood. Lesions tend to enlarge gradually before stabilizing or regressing. Familial AN is a rare genodermatosis that seems to be transmitted in an autosomal dominant fashion with variable phenotypic penetrance. The lesions typically begin during early childhood, but may manifest at any age. The condition often progresses until puberty at which time it stabilizes or regresses. Drug-induced AN, although uncommon, may be induced by several medications, including nicotinic acid, insulin, pituitary extract, systemic corticosteroids, and diethylstilbestrol. Rarely, triazinate, oral contraceptives, fusidic acid, and methyltestosterone also have been associated with AN. The lesions of AN may regress following the discontinuation of the offending medication. Malignant AN, which is associated with internal malignancy, is the most worrisome of the variants of AN because the underlying neoplasm is often an aggressive cancer. AN has been reported with many kinds of cancer, but, by far, the most common underlying malignancy is an adenocarcinoma of gastrointestinal origin, usually a gastric adenocarcinoma. Malignant AN is clinically indistinguishable from the benign forms; however, one must be more suspicious if the lesions arise rapidly, are more extensive, are symptomatic, or are in atypical locations. Regression of AN has been seen with treatment of the underlying malignancy and reappearance may suggest recurrence or metastasis of the primary tumor.

Mixed-type AN refers to those situations in which a patient with one of the above types of AN develops new lesions of a different etiology. An example of this would be an overweight patient with obesity-associated AN who subsequently develops malignant AN. Patients usually present with an asymptomatic area of darkening and thickening of the skin.[13] Pruritus occasionally may be present. Lesions begin as hyperpigmented macules and patches and progress to palpable plaques. In approximately one third of cases of malignant AN, patients are presented with skin changes before any signs of cancer. In another one third of cases, the lesions of AN arise simultaneously with the neoplasm. In the remaining one third of cases, the skin findings manifest sometime after the diagnosis of cancer. Malignant AN has been reported to appear abruptly and exuberantly and may be associated with a higher rate of pruritus. Onset may be related to medication or supplement usage.

AN is most commonly associated with disorders associated with insulin resistance, including obesity, type 2 diabetes, and the PCOS.[14] In these cases, hyperinsulinemia is thought to play a pivotal role. Acrochordons (skin tags) are often found in and around the affected areas. Occasionally, lesions of AN may be present on the mucous membranes of the oral cavity, nasal and laryngeal mucosa, and esophagus. The areola of the nipple also may be affected. Eye involvement, including papillomatous lesions on the eyelids and conjunctiva, may occur. Nail changes such as leukonychia and hyperkeratosis have been reported. The lesions of malignant AN are clinically indistinguishable from benign AN. Understanding the connection between AN and insulin resistance is critical for clinicians. Patients with AN are at risk for all of the components of the metabolic syndrome: obesity, hypertension, elevated triglycerides, low high-density lipoprotein, and glucose intolerance.[15–17] The metabolic syndrome present in 34% of American adults yields a risk of heart disease equivalent to smoking and in adults increases the risk of the development of diabetes 3.5-fold within five years[18–20] Like obesity, PCOS is associated with insulin resistance, hyperinsulinemia, and AN. Between 5 and 33% of patients with PCOS have AN.[21,22] This syndrome includes increased synthesis of ovarian and adrenal androgens and inhibition of hepatic synthesis of sex hormone-binding globulin.[23–25] Insulin resistance is also hypothesized to have a role in the development of acne, skin tags, male vertex balding, myopia, and epithelial cell cancers. Patients may have multiple underlying diseases. The first step in evaluation should be identification of the underlying condition. We recommend obtaining certain basic studies, particularly in all overweight adults and children without a known history of insulin resistance.[26–28] Overweight in adults is defined as a body mass index (BMI, weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared) of 25 kg/m2 or greater. In children and adolescents, overweight is defined as at least the 85th percentile of the sex-specific BMI-for-age growth chart; the child is considered obese when the BMI z score exceeds the 95th percentile for age and gender. Studies should include blood pressure (BP), fasting lipoprotein profile, fasting glucose, hemoglobin A1C, fasting insulin, and alanine aminotransferase (ALT). Any abnormalities should prompt communication with the primary provider or referral to an endocrinologist.

Improvement of the skin lesions is often the patient's primary concern. No randomized, controlled trials exist for any treatment of AN. Multiple case reports suggest that AN improves with treatment of its underlying condition. No treatment of choice exists for AN. The goal of therapy is to correct the underlying disease process. Treatment of the lesions of AN is for cosmetic reasons only. Correction of hyperinsulinemia often reduces the burden of hyperkeratotic lesions. Likewise, weight reduction in obesity-associated AN may result in resolution of the dermatosis. Cessation of inciting agent in drug-induced AN often results in resolution. Acipimox may be used in place of nicotinic acid to induce AN regression while improving the lipid profile. Topical medications that have been effective in some cases of AN include keratolytics (e.g., topical tretinoin 0.05%, ammonium lactate 12% cream, or a combination of the two) and triple-combination depigmenting cream (tretinoin 0.05%, hydroquinone 4%, fluocinolone acetonide 0.01%) nightly with daily sunscreen.[14] Calcipotriol, podophyllin, urea, and salicylic acid also have been reported, with variable results.

Footnotes

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Brown J, Winkelmann RK. Acanthosis nigricans: A study of 90 cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 1968;47:33–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barbieri RL, Ryan KJ. Hyperandrogenism, insulin resistance, and acanthosis nigricans syndrome: A common endocrinopathy with distinct pathophysiologic features. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1983;147:90–101. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(83)90091-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fine RM. Acanthosis nigricans. Int J Dermatol. 1991;30:17–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1991.tb05872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Curth HO. Acanthosis nigricans: birth defects. Orig Art Ser. 1971;3:31–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilkison C, Stuart CA. Assessment of patients with acanthosis nigricans skin lesion for hyperinsulinemia, insulin resistance and diabetes risk. Nurse Pract. 1992;17:26–44. doi: 10.1097/00006205-199202000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tabandeh H, Gopal S, Teimory M, Wolfensberger T, Luke IK, Mackie I, et al. Conjunctival involvement in malignancy-associated acanthosis nigricans. Eye (Lond) 1993;7:648–51. doi: 10.1038/eye.1993.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Groos EB, Mannis MJ, Brumley TB, Huntley AC. Eyelid involvement in acanthosis nigricans. Am J Ophthalmol. 1993;115:42–5. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)73522-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flier JS, Young JB, Landsberg L. Familial insulin resistance with acanthosis nigricans, acral hypertrophy and muscle cramps. N Engl J Med. 1980;30:97–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198010233031704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Annos T, Taymor ML. Ovarian pathology associated with insulin resistance and acanthosis nigricans. Obstet Gynecol. 1981;58:662–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grasinger CC, Wild RA, Parker IJ. Vulvar achanthosis nigricans: A marker for insulin resistance in hirsute women. Fertil Steril. 1993;593:583–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conway GS, Jacobs HS. Clinical implications of hyperinsulinemia in women. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1993;39:623–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1993.tb02419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Higgins SP, Freemark M, Prose NS. Acanthosis nigricans: a practical approach to evaluation and management. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:2–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Imperato-McGinley J, Peterson RE, Sturla E, Dawood Y, Bar RS. Primary amenorrhea, associated with hirsutism, acanthosis nigricans, dermoid cysts of the ovaries and a new type of insulin resistance. Am J Med. 1978;65:389–95. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(78)90838-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stuart CA, Gilkison CR, Smith MM, Bosma AM, Keenan BS, Nagamani M. Acanthosis nigricans as a risk factor for non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1998;45:22–5. doi: 10.1177/000992289803700203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flier JS, Fastman RC, Minakes KL, Matteson D, Rowe JW. Acanthosis nigricans in obese women with hyperandro genism: Characterization of an insulin-resistant state distinct from the type A and B syndromes. Diabetes. 1985;34:101–7. doi: 10.2337/diab.34.2.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hud JA, Cohen JB, Wagner JM, Cruz PD. Prevalence and significance of acanthosis nigricans in an adult obese population. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:941–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hrrnandez Perez E. On the classification of acanthosis nigricans. Int J Dermatol. 1994;36:605–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1984.tb05698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schwartz RA. Acanthosis nigricans. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:1–19. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(94)70128-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rogers DL. Acanthosis nigricans. Semin Dermatol. 1991;10:160–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsuoka LY, Wortsman J, Gavin JR, Goldman J. Spectrum of endocrine abnormalities associated with acanthosis nigricans. Am J Med. 1987;83:719–25. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(87)90903-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rendon MI, Cruz PD, Jr, Sontheimer RD, Bergstresser PR. Acanthosis nigricans: A cutaneous marker of tissue resistance to insulin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21:461–9. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(89)70208-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maitra SK, Rowland Payne CM. The obesity syndrome and acanthosis nigricans. Acanthosis nigricans is a common cosmetic problem providing epidemiological clues to the obesity syndrome, the insulin-resistance syndrome, the thrifty metabolism, dyslipidaemia, hypertension and diabetes mellitus type II. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2004;3:202–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1473-2130.2004.00078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barbieri RL, Ryan KJ. Hyperandrogenism, insulin resistance, and acanthosis nigricans syndrome: A common endocrinopathy with distinct pathophysiologic features. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1983;147:90–101. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(83)90091-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuroki R, Sadamoto Y, Imamura M, Abe Y, Higuchi K, Kato K, et al. Acanthosis nigricans with severe obesity, insulin resistance and hypothyroidism: improvement by diet control. Dermatology. 1999;198:164–6. doi: 10.1159/000018096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eberting CL, Javor E, Gorden P, Turner ML, Cowen EW. Insulin resistance, acanthosis nigricans, and hypertriglyceridemia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:341–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.10.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stuart CA, Gilkison CR, Smith MM, Bosma AM, Keenan BS, Nagamani M. Acanthosis nigricans as a risk factor for non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1998;37:73–9. doi: 10.1177/000992289803700203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brown J, Winklemann RK. Acanthosis nigricans: A study of 90 cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 1968;47:33–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stuart CA, Pate CJ, Peters EJ. Prevalence of acanthosis nigricans in an unselected population. Am J Med. 1984;87:269–72. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(89)80149-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]