Abstract

Background:

Cicatricial alopecias have a significant impact on the psychological status, quality of life, and social interaction of those suffering from it. Till date, limited or no data have been available regarding the psychosocial and quality of life aspects of cicatricial alopecias.

Aims:

To assess the psychosocial impact of cicatricial alopecias.

Materials and Methods:

Thirty patients fulfilling the criteria for cicatricial alopecia irrespective of their age and sex were included in the study. Psychosocial assessment was carried out in 23 patients who were capable of responding to the questionnaire, using an adopted and suitably modified version of Women's Androgenetic Alopecia Quality of Life Questionnaire.

Results:

We observed that 73.9% of our patients with cicatricial alopecias had moderate to severe psychosocial impact due to their hair loss. Patients of younger age group and with inactive disease, suffered from greater psychosocial impact of the disease. Patients with slight hair loss also had considerable psychological distress. The chronicity of disease duration did not seem to reduce the psychosocial impact of the disease. Both married and unmarried patients suffered equally from the psychosocial impact of the disease.

Conclusion:

The management of cicatricial alopecias needs a holistic approach. In addition to laying an emphasis on early diagnosis aided by clinco-pathological correlation, to prevent irreversible hair loss, the psychosocial impact of the disease should also be taken into consideration and addressed by the treating dermatologist.

Keywords: Cicatricial alopecias, modified women's androgenetic alopecia quality of life questionnaire, psychosocial impact

Introduction

Cicatricial alopecias encompass a diverse group of poorly understood disorders that are characterized by a common final pathway of replacement of the follicular structure by fibrous tissue and irreversible hair loss.[1] Destruction of the hair follicle can result from a primary folliculo centric disease leading to primary cicatricial alopecia or a secondary insult causing secondary cicatricial alopecia.[2] The North American Hair Research Society (NAHRS)-sponsored workshop put forward a working classification of primary cicatricial alopecias in 2001, which subdivides the primary cicatricial alopecias according to the predominant inflammatory cell type present and those cicatricial alopecia with inconclusive clinical and histopathological finding are placed under the non-specific category.[3] Various non-follicular conditions of the scalp can lead to secondary cicatricial alopecias, which include traumatic, infectious, inflammatory, neoplastic, and genetic conditions.[4] Cicatricial alopecias can be particularly challenging clinically, as patients tend to present late due to non-recognition at an early stage, and treatment options are poorly defined and often limited in effect.[5]

Hair loss has a significant impact on the psychological status, quality of life, and social interaction of those suffering from it. While this is essentially true for all forms of cosmetically disturbing hair loss, the situation is more aggravated in cicatricial alopecias, as they are usually irreversible and often progressive in nature.[6] Although there are many studies.[7–13] addressing the psychosocial impact of non-cicatricial alopecias, the information on the psychosocial impact of cicatricial alopecias is sparse. This study was undertaken to assess the psychosocial impact of cicatricial alopecias.

Materials and Methods

The study was a descriptive study consisting of 30 consecutive patients of irrespective of their age and sex, attending the dermatology out-patient department of a tertiary care institute from September 2008 to June 2010. Data including patient's age, gender, occupation, marital status, age of onset of disease, disease duration, and symptoms, morphology of the lesions, and site of involvement were recorded. The various hair care practices followed by the patients were noted. The surface area of scalp involvement was recorded according to the alopecia areata investigational guidelines.[14] Mucocutaneous and nail changes, if any, were recorded. Potassium hydroxide mount (KOH), gram staining, culture sensitivity, and antinuclear antibody testing were undertaken whenever necessary.

An elliptical scalp biopsy was taken from the lesional area (centre/periphery), for histopathological evaluation in all cases except those with tinea capitis (8 cases), which were diagnosed mostly on the basis of clinical presentation, KOH examination and/or therapeutic response to griseofulvin. All histopathologic slides were interpreted using defined systematic criteria, as defined by the North American Hair Research Society guidelines.[3]

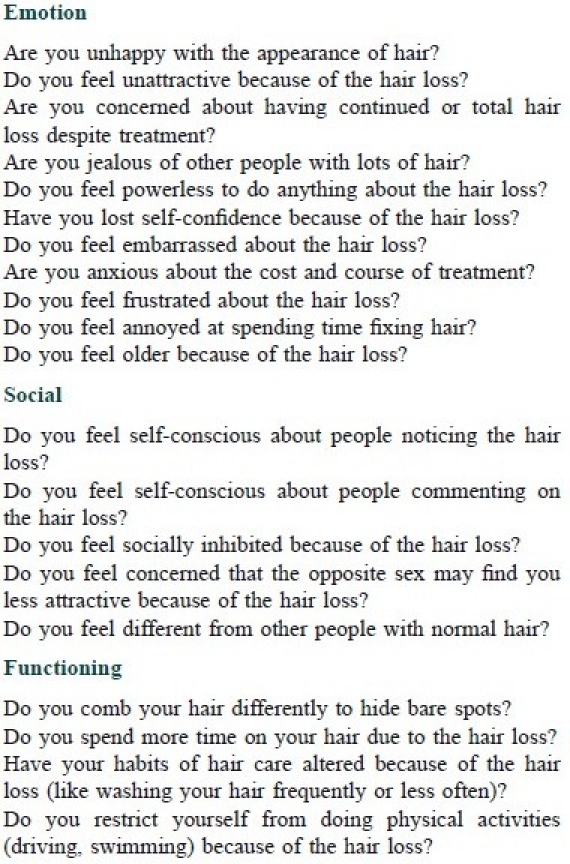

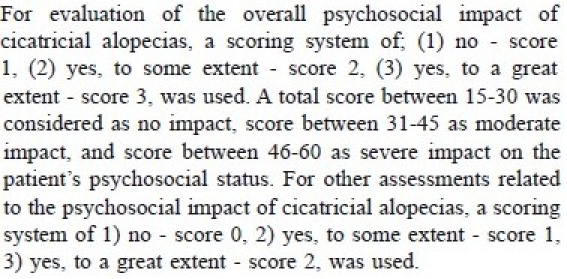

Of the 30 patients, psychosocial assessment due to the disease was carried out in 23 patients who were capable of responding to the questionnaire. The psychosocial impact was assessed using an adopted and suitably modified version of Women's Androgenetic Alopecia Quality of Life Questionnaire (WAA-QOL).[15] We modified the questionnaire to suit our population and resultant number of questions was 20. Furthermore, we simplified the scoring system to make the questionnaire more comprehensible by scoring each questions on a series of three answers. We also grouped these 20 questions into three sub-scales to measure the psychosocial impact of cicatricial alopecias on the emotional state, social life, and functioning of our patients. Unlike the original questionnaire, the questions were not asked in relation to the past week. The questions asked are shown in Appendix I and its scoring system in Appendix II.

Appendix I.

Modified WAA-QOL

Appendix II.

Scoring system for the evaluation of psychosocial impact of cicatricial alopecias

The results were tabulated and analyzed using SPSS 15 software. Comparison of group differences in gender, disease activity, marital status, in relation to psychosocial impact, was performed by Mann-Whitney's test. The relationship between disease variables (age, disease duration) and the psychosocial impact were examined using Spearman's rho correlation coefficients . When comparing the scalp surface area involvement and the psychosocial impact, Kruskal-Wallis’ test was performed.

Results

The observations made in our study has been put under two categories:

-

Clinical and histopathological characteristics of cicatricial alopecias.

Of the 30 cases with cicatricial alopecias, 19 were females (63.3%) and 11 were male (36.7%) patients. Their ages ranged from 5-65 (mean: 28.3) years. These cases were categorized into primary and secondary cicatricial alopecias. According to the NAHRS[3] working classification of primary cicatricial alopecias, they were categorized into- lymphocytic, neutrophilic, mixed and non-specific cicatricial alopecias. The secondary cicatricial alopecias were classified as those caused by infections, sclerosing disorders, and vesiculo-bullous disorders. There were 19 patients (63.3%) of primary cicatricial alopecias and 11 patients (36.7%) of secondary cicatricial alopecias.

-

Psychosocial impact of cicatricial alopecias.

For the evaluation of psychosocial impact 23 patients were included, which comprised of 9 males and 14 female patients. Their age ranged from 13-65 (mean- 34.3) years. The mean total duration of disease was 3.1 (range 0.07-20) years. It was seen that 73.9% of our patients had moderate to severe psychosocial impact due to their hair loss.

Gender difference in the psychosocial impact variables

We observed no significant gender difference (P=0.488) in the psychosocial impact of cicatricial alopecias. However, the social domain was found to be more affected in females compared to males, although the difference did not achieve statistical significance.

Age and psychosocial impact

Although an inverse correlation of age of the patient with the modified WAA-QOL (r=-0.055, P=0.804) and its emotion (r=-0.170, P=0.438) and functioning (r=-0.054, P=0.807) domains was noted, it was not statistically significant.

Duration of disease and psychosocial impact

Duration of the disease had no significant correlation with the modified WAA-QOL (r=0.273, P=0.207), and its emotion (r=0.079, P=0.722), social (r=0.385, P=0.07), functioning (r=0.12, P=0.585) domains.

Disease activity and psychosocial impact

Patients with inactive disease did have a higher mean WAA-QOL score but the difference did not achieve statistical significance (P=0.089).

Marital status and psychosocial impact

We observed no significant difference in the mean scores of WAA-QOL (P=0.789) between the married and unmarried groups.

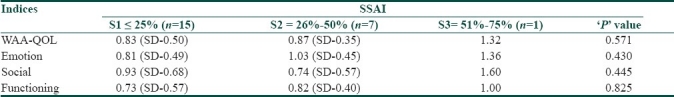

Scalp surface area involvement (SSAI) and psychosocial impact

The surface area of scalp involvement was recorded according to the alopecia areata investigational guidelines.[14] The mean of WAA-QOL and its domains in each of the SSAI groups were compared. We observed no statistically significant difference in the mean scores of WAA-QOL and its domains, between the three SSAI groups [Table 1].

Table 1.

Difference in mean scores of WAA-QOL and its domains and SSAI

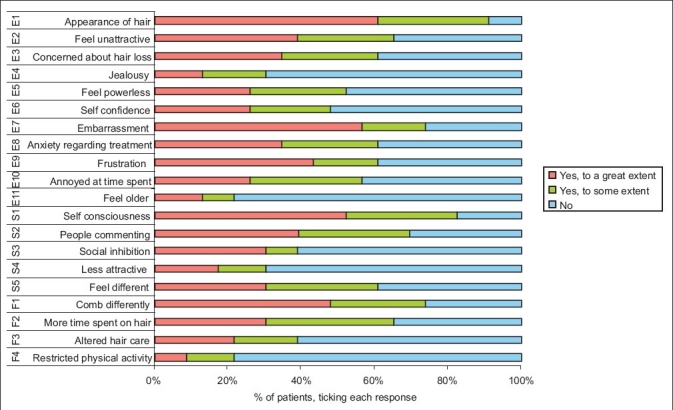

WAA-QOL- the response pattern

The overall percentage of patients ticking each response and pattern of response in the WAA-QOL Questionnaire are given in [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Result of the WAA-QOL Questions

Discussion

Although cicatricial alopecias are not life threatening conditions, affected individuals may experience substantial psycho-social distress. We observed that that 73.9% of our patients had moderate to severe psychosocial impact due to their hair loss. This clearly reflects the negative impact of cicatricial alopecias on the patient's psychosocial state.

Studies have verified the psychosocial impact of hair loss in both men and women.[7,9,12] Studies conducted previously on psychological effects of androgenetic alopecia (AGA),[9,12] have found women with AGA more psychosocially debilitated than other groups. It was probably because these studies dealt with androgenetic alopecia, which may be regarded as more “normal” or expected for and by men.[9] We examined the relation of gender with the psychosocial impact of cicatricial alopecias in our patients. The social domain of the questionnaire was found to be more affected in females patients (P=0.05), as reflected by a higher mean (1.11) compared to males (0.58). This could be partly due to the societal norms, which make women more conscious of their physical appearance, lack of which could lead to refrain from social activities. However, apart for the social domain both the sexes seemed to be equally affected by their hair loss. Hence, this pathological form of hair loss can be very distressing psychosocially to those suffering from it, and no gender escapes from its impact.

An inverse correlation of age of the patient and the modified WAA-QOL and its domains was seen in our study, though not statistically significant. It is understandable that an esthetically better appearance is more important in younger patients. Lack of which can make them feel older and have a negative impact on their self-confidence, perception of physical unattractiveness, and cause embarrassment, and frustration. In a study by Wells et al.[16] on psychological correlates of hair loss in 182 balding men, it was found that lower self-esteem, higher introversion, and feeling of unattractiveness were more marked in younger men with AGA, and they stated that socialization is again more affected with premature hair loss.

The duration of cicatricial alopecias in our patients ranged from 25 days to 20 years. Surprisingly, the duration of the disease had no significant impact on the modified WAA-QOL (P=0.207) or its domains. Our observation was similar to that made by Williamson et al,[17] who assessed the effect of hair loss on quality of life in 70 patients.

We found no significant difference in the mean of modified WAA-QOL or its domains among the married and unmarried patients. Despite the fact that one would expect more psychosocial impact among the unmarried patients, we observed almost an equal psychosocial impact among the married and unmarried groups with cicatricial alopecias. It could be due to the fact that most of our married subjects were females (12/16 cases), reflecting less perseverance and tolerance by their spouses, regarding their hair loss in a male dominant society.

It is possible that individuals with limited hair loss are able to cover their loss with remaining hair and so are likely to experience less psychological problems.[18] Cash evaluated the psychological effects of AGA in men[19] and women,[9] and found that patients with more extensive hair loss had significantly higher psychosocial distress. In a study, by Schmidt et al,[20] on- strategies of coping and quality of life in women with alopecia, identified a subset of patients in their study with no visible hair loss who also showed a significantly lower quality of life. These patients were found to be maladjusted with their hair loss. We did not find any significant difference in the mean scores of WAA-QOL and its domain among patients with different degree of hair loss. The reason for obtaining similar scores among the different groups in our study could be due to the fact that majority of our patients 65.22% (15/23 cases) fell into a single category of hair loss involving less than 25% of scalp surface, and another 30.43% (7/23 cases) had hair loss involving 26-50% of the scalp. Most of the patients in the second group had hair loss towards the lower side of the range. Nevertheless, the fact that even patients with slight visible hair loss can have considerable psychological distress should be acknowledged.

The results of our study bore some resemblance to results obtained during the developmental process of the original questionnaire in regard to the questions ranked by our patient. Women with AGA, ranked questions related to negative feelings about their appearance, feelings of unattractiveness, annoyance at the amount of time spent on hair, trying to cover bare spots; high in their study. Whereas, questions related to restriction of activities, or feeling older were not ranked highly important. It is evident from our study that cicatricial alopecias have an enormous amount of psychological impact on those suffering from it.

Conclusion

The management of cicatricial alopecias need a holistic approach. In addition to laying an emphasis on early diagnosis aided by clinico-pathological correlation, to prevent irreversible hair loss, the psychosocial impact of the disease should also be taken into consideration and addressed by the treating dermatologist.

Footnotes

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Ngwanya RM. Primary cicatricial alopecia. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44(Suppl. 1):18–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2005.02802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Berker DA, Messenger AG, Sinclair RD. Disorders of hair. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C, editors. Rook's Textbook of Dermatology. 7th ed. 2004. pp. 63.1–63.71. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olsen EA, Bergfeld WF, Cotsarelis G, Price VH, Shapiro J, Sinclair R, et al. Summary of North American hair research society (NAHRS)-sponsored workshop in cicatricial alopecia, Duke University Medical Center, February 10 and 11, 2001. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:103–10. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2003.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finner AM, Otberg N, Shapiro J. Secondary cicatricial and other permanent alopecias. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21:279–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2008.00210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McElwee KJ. Etiology of cicatricial alopecias: A basic science point of view. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21:212–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2008.00202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harries MJ, Trueb RM, Tosti A, Messenger AG, Chaudhry I, Whiting DA, et al. How not to get scar(r)ed: Pointers to the correct diagnosis in patients with suspected primary cicatricial alopecia. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:482–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.09008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van der Donk J, Hunfeld JA, Passchier J, Knegt-Junk KJ, Nieboer C. Quality of life and maladjustment associated with hair loss in women with alopecia androgenetica. Soc Sci Med. 1994;38:159–63. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90311-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Camacho F, García-Hernández M. Psychological features of androgenetic alopecia. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2002;16:476–80. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2002.00475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cash TF, Price VH, Savin RC. Psychological effects of androgenetic alopecia on women: Comparisons with balding men and with female control subjects. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:568–75. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(93)70223-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Güleç AT, Tanrýverdi N, Dürü C, Saray Y, Akçalı C. The role of psychological factors in alopecia areata and the impact of the disease on the quality of life. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:352–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruiz-Doblado S, Carrizosa A, Garcia-Hernandez MJ. Alopecia areata: psychiatric comorbidity and adjustment to illness. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:434–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2003.01340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van der Donk J, Passchier J, Knegt-Junk C, van der Wegen-Keijser MH, Nieboer C, Stolz E, et al. Psychological characteristics of women with androgenetic alopecia: A controlled study. Br J Dermatol. 1991;125:248–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1991.tb14749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koo J, Shellow W, Hallman C, Edwards J. Alopecia areata and increased prevalence of psychiatric disorders. Int J Dermatol. 1994;33:849–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1994.tb01018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oslen E, Hordinsky M, McDonald-Hull S, Price V, Roberts J, Shapiro J, et al. Alopecia areata investigational assessment guidelines. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:242–6. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70195-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dolte KS, Girman CJ, Hartmaier S, Roberts J, Bergfeld W, Waldstreicher J. Development of a health-related quality of life questionnaire for women with androgenetic alopecia. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2000;25:637–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2000.00726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grimalt R. Psychological aspects of hair disease. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2005;4:142–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1473-2165.2005.40218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williamson D, Gonzalez M, Finlay AY. The effect of hair loss on quality of life. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:137–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2001.00229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hunt N, McHale S. The psychological impact of alopecia. BMJ. 2005;331:951–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7522.951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cash TF. The psychological effects of androgenetic alopecia in men. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:926–31. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(92)70134-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmidt S, Fischer TW, Chren MM, Strauss BM, Elsner P. Strategies of coping and quality of life in women with alopecia. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:1038–43. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]