Abstract

Background:

Although psoriasis generally does not affect survival, it certainly has a number of major negative effects on patients, demonstrable by a significant detriment to quality of life.

Aims:

We have done a study with the objective of assessing the clinical variables adversely affecting quality of life in patients diagnosed with psoriasis.

Materials and Methods:

This study is a cluster analysis of 50 consecutive consenting patients with psoriasis, of both sexes, aged over 18 years, attending the dermatology outpatient department of a tertiary care center. We measured the clinical severity using psoriasis area severity index and health-related quality of life using psoriasis disability index (PDI). Statistical analysis was performed using unpaired independent student's t-test, analysis of variance (and Scheffe's post hoc test as appropriate) and Pearson's correlation coefficients.

Results:

There was a significant correlation between the physician-rated severity of psoriasis and the extent of impact of psoriasis on physical disability as measured by the PDI. We have identified that a younger age at onset of disease and self-reported stress exacerbators suffer greater disability in most aspects of quality of life.

Conclusions:

On the basis of this study, we would recommend that psoriasis patients especially with severe disease require a more holistic treatment approach that encompasses both medical and psychological measures.

Keywords: Disability, psoriasis, quality of life

Introduction

The definition of psoriasis as “a common, chronic, disfiguring, inflammatory condition of the skin”[1] does not significantly consider the psychological impact of the disease. And though psoriasis generally does not affect survival, it certainly has a number of major negative effects on patients, demonstrable by the significant detriment to quality of life.[2] We have done a study of psoriasis patients with the objective of identifying the clinical variables adversely affecting their quality of life (QoL).

Material and Methods

This study is a cluster analysis of 50 consecutive consenting patients with psoriasis, of both sexes, aged above 18 years, attending the dermatology outpatient department of a tertiary health care center. The institutional ethics committee approved the study. A detailed history with special relevance to known risk factors and physical examination was obtained in all cases. We measured the clinical severity using psoriasis area severity index (PASI). Diagnosis of psoriasis was done clinically. Any nonconsenting patient or patients with other concomitant medical or dermatological diseases was excluded from the study.

To measure the QoL, patients were instructed to complete a multidimensional quality of life assessment questionnaire comprising the psoriasis disability index[3,4] (PDI 1990 version). Prior permission for the use and modification of the scales was obtained for the questionnaire from the author. The original PDI is a 15-item standardized questionnaire designed to quantify the functional disability in aspects of daily activities, employment, personal relationships, leisure, and treatment effects in psoriasis patients. The scoring of each question is answered by the patients on a series of four answers; not at all (scores 0), a little (scores 1), a lot (scores 2), very much (scores 3). The resulting score ranged from 0 to 45. The higher the score, the more the quality of life is impaired. The PDI can also be expressed as a percentage of maximum possible score of 45. The question base was 4 weeks. We used a modified version of the PDI, which contained 16 questions, and thus the maximum total score adds to 48.

Statistical analysis was performed using the software “Statistica” on variables of specific interest to this study. Comparison of group differences in gender, pruritus, marital status, family history, and clinical severity groups were performed by unpaired independent student's t-test. When the comparison included more than two variables as among various addictions and employment, analysis of variance (and Scheffe's post hoc test as appropriate) was performed. The relationship between disease variables (age at onset, disease duration, clinical severity scores) was examined using Pearson's correlation coefficients.

Results

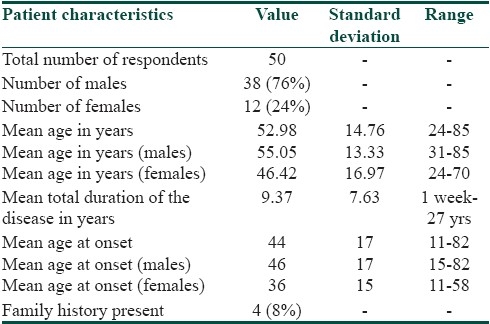

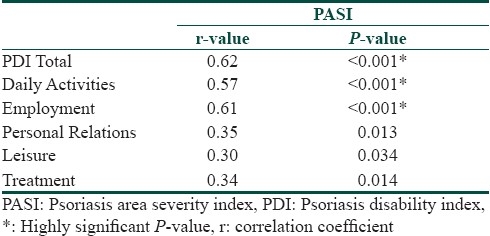

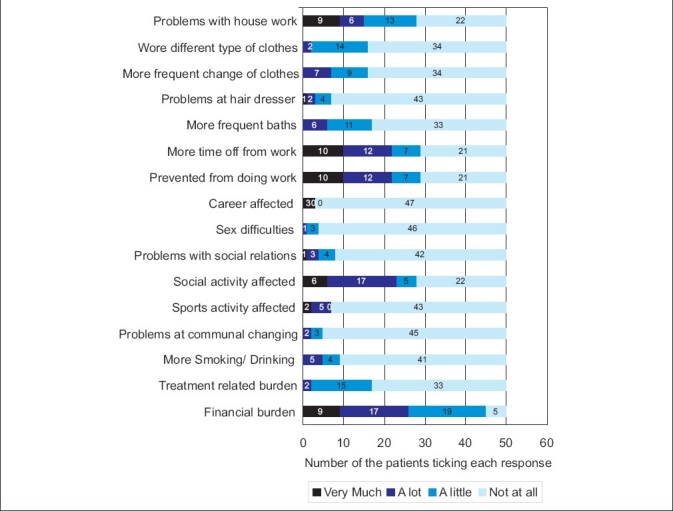

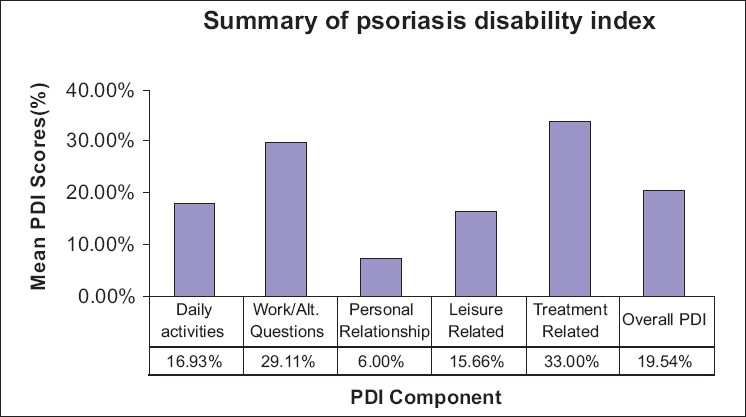

The study group consisted of 50 consecutive consenting patients with psoriasis attending the OPD of dermatology department of a tertiary health care center. The characteristics of the respondents are given in the Table 1. Twelve percent of the patients attributed the exacerbation of disease due to stressful life events. There was no significant difference in clinical severity or total PDI score between the two genders. However, men were significantly affected at the workplace than women. The mean score of PASI in our cases was 11.76 (out of the maximum possible score of 72) and mean score of PDI was 9.38 (out of the maximum possible score of 48). There was no significant difference in clinical severity or physical disability between the two groups based on the patients present age. However, we observed a negative correlation of age of onset with PDI (r =-0.29, P=0.03). Thus, patients with earlier age of onset of psoriasis were associated with worse physical disability scores than those with late onset of psoriasis. Disease duration had no significant impact on the mean PASI or PDI. Those patients with stress as a precipitating factor showed worse physical disability scores. Pruritus, family history of psoriasis, marital status, current employment status, and addictions bore no significant impact on clinical severity or disability. PDI scores were not significantly different among the different subtypes of psoriasis. Using Pearson's correlation coefficient we observed significant correlation of the PASI score with the total PDI and all its subdivisions [Table 2]. The percentage of patients ticking each response and the overall pattern of response in the PDI is given in Figures 1 and 2, respectively.

Table 1.

Characteristics of respondents

Table 2.

Pearson's correlation coefficient to evaluate the relation between PASI scores and PDI scores (total and subdivisions)

Figure 1.

The response of patients to the psoriasis disability index questionnaire

Figure 2.

The percentage patients ticking each response in the psoriasis disability index questionnaire

Discussion

Psoriasis represents a life long burden for the affected patients. There is a general consensus among research studies that objective clinical severity alone is insufficient as an assessment of the burden of disease. It is the inner world of the patient that clinicians need to assess. One study reported that only 39% of patients who had psoriasis with clinically relevant distress were identified correctly by dermatologists.[5] And when physicians did identify patients as clinically distressed (anxiety or depression), further action to address such difficulties through referral to appropriate specialists was taken in only one-third of cases despite the potential effects of distress on adherence to treatment and the effectiveness of treatment.[6,7] Therefore, QoL measures are being assigned increasing importance in the evaluation of health care outcomes.[8] Indian clinicians and researchers have recently started to give importance to this aspect of psoriasis. Our study will be discussed to give a better perspective of what disability psoriasis patients experience both physically and psychosocially.

In our study, a younger age onset was associated with greater physical disability. Fortune et al,[9] found that patients with earlier age of onset had higher scores of PASI and PDI. Ginsburg,[10] in her study of stigmatization found that being older at onset of psoriasis protects people against anticipating rejection, feeling sensitive to opinion of others, feeling of guilt and shame, and secretiveness. Our study is in concordance with this finding. In our study, males were more significantly affected at workplace than females. Gupta and Gupta[11] also showed that men report more occupational impairment but Koo et al,[12] found that women reported more severe disease than man. Surprisingly the duration on of the disease had no significant impact on the mean PASI or mean PDI scores. Similar findings had been reported by Fortune et al.[7] This suggests that the range of impact of psoriasis is not simply reducible to the chronicity of the disease.

Some of the most persuasive indications of a link between stress and psoriasis come from patients themselves, with studies illustrating that 37% to 88% patients[13–19] believe that stress or psychological distress is a factor influencing their condition. In recent years, the conceptualization of stress in the context of psoriasis has developed to include not only significant life events[20] but also chronic, recurrent, low-grade stresses, or daily hassles that occur largely as a result of living with a chronic disfiguring disease.[21] Self-reported psoriasis “stress reactors” were more likely to be female and to have a family history of psoriasis, greater disease severity, higher levels of psoriasis-related stress, and greater impairment in psoriasis-related quality of life.[19,22] The question as to how stress modulates the physiologic homeostasis is complex and is likely to involve interactions between many cardiovascular, endocrine, and immunologic parameters.[9] Hypocortisolism may be an important feature of stress-responsive psoriasis.[23–25] Thus the “brain-skin axis” is a relatively new concept connecting stress and psoriasis. An interesting study by Schmidt-Ott and colleagues[24] suggest that stress induces changes in the number of cytotoxic T lymphocytes, and this may be associated with exacerbation of psoriasis.

Many of our patients did not find pruritus a bothersome symptom so as to affect the quality of life indices, which is unexpected. Higgins et al,[26] found that smoking and alcohol have an affect on psoriasis. Increased alcohol consumption is recognized as a stress response and there has been much debate as to whether increased alcohol consumption is a case or a consequence of psoriasis. However, our study did not observe any correlation between additions and quality of life index.

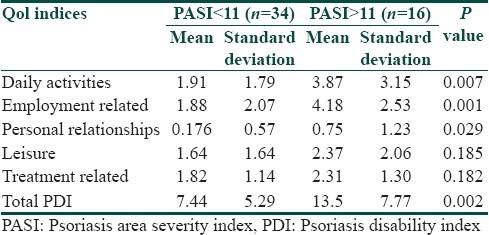

We observed a highly significant correlation between the clinical severity (PASI) with the total PDI scores and all its subdivisions [Table 1]. Our findings are in concordance with other investigators like Finlay et al[27] and Aschroft et al.[28] Feldman[29] has argued that for clinical trial criteria there should be at least 10% BSA involvement and a PASI of >11. Thus to further examine whether this cut off point for PASI (PASI=11) could also serve to delineate a subgroup of people with more or less physical disability we divided our patients into two groups based on the clinical severity Group I PASI<11 (n=34), Group II PASI >11 (n=16). We found that the total PDI was statistically different in the two groups and among all the PDI subdivisions except leisure and treatment related scores [Table 3]. The response pattern in our patients shows how the financial and treatment related problems adversely affect the quality of life in our patient who are mostly of lower socioeconomic group [Figure 2]. In response to what extent has psoriasis or treatment made their home messy or untidy none answered very much and only four percent said a lot. The reason for this could be that topical treatments in the form of coal tar is much better tolerated psychologically in our patients since indigenous practices such as oil massage are considered as healthy and beneficial in this region.

Table 3.

Difference in the mean score of the total PDI between two clinical severity groups; Group1: PASI<11, Group 2 PASI>11

The next decade will reveal findings from studies currently being undertaken by research teams worldwide regarding the use of brain imaging in the context of acute stress in psoriasis, the role of early adversity as a risk factor in chronicity, in-depth examinations of the interplay between stress and the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal axis system and interventions targeting specific psychologic processes and outcomes.[9] For the present the approaches to management of psychosocial issues include anxiolytics, cognitive behavior therapy,[9] mindfulness meditation-based stress reduction, individual and group psychotherapy, music therapy, hypnosis, and psoriasis support groups.[30] A new approach is the “patient-centered care,” which refers to the health care that is closely congruent with, and responsive to the patients wants, needs, and preferences.[31] Examples of patient-centered care for the treatment of psoriasis include engaging in two-way communication, being an empathic listener and providing reasonable expectations for treatment and outcomes. One should also involve the patient in decision-making, communicate care by touching lesions, be aware of psychological distress in the patient and avoid transferring feelings of inadequacy regarding treatment. Thus, one should communicate information that is understandable, useful, and helpful to motivate the patient.

Conclusion

Overall, there was significant correlation between the physician rated severity of psoriasis and the extent of impact of psoriasis on physical disability as measured by the PDI. Even though western studies show disparity between clinical severity and quality of life, our study demonstrates that patients with a greater severity of the disease suffer greater disability, both physically and mentally, which results in a considerable handicap. We have identified that a younger age at onset of disease and self-reported stress exacerbators suffer greater disability in most aspects of quality of life. On the basis of this study, we would recommend that psoriasis patients, especially those with severe disease require a more holistic treatment approach that encompasses both medical and psychological measures.

Footnotes

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Griffiths C, Camp R, Barker J. In: In, Rook's textbook of dermatology. 7th ed. Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C, editors. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 2004. p. 35.1. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krueger GG, Feldman SR, Camisa C, Duvic M, Elder JT, Gottlieb AB, et al. Two considerations for patients with psoriasis and their clinicians: What defines mild, moderate, and severe psoriasis? What constitutes a clinically significant improvement when treating psoriasis? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:281–5. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2000.106374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Finlay AY, Coles EC. The effect of severe psoriasis on the quality of life of 369 patients. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:236–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1995.tb05019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finlay AY, Kelly SE. Psoriasis: An index of disability. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1987;12:8–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1987.tb01844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richards HL, Fortune DG, Weidmann A, Sweeney SK, Griffiths CE. Detection of psychological distress in patients with psoriasis: Low consensus between dermatologist and patient. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:1227–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.06221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Renzi C, Picardi A, Abeni D, Agostini E, Baliva G, Pasquini P, et al. Association of dissatisfaction with care and psychiatric morbidity with poor treatment compliance. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:337–42. doi: 10.1001/archderm.138.3.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richards HL, Fortune DG, O’Sullivan TM, Main CJ, Griffiths CE. Patients with psoriasis and their compliance with medication. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:581–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Finlay AY. The outcomes movement and new measures of psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:502–3. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(97)80253-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fortune DG, Richards HL, Griffiths CE. Psychologic factors in psoriasis: Consequences, mechanisms, and interventions. Dermatol Clin. 2005;23:681–94. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2005.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ginsburg IH, Link BG. Psychosocial consequences of rejection and stigma feelings in psoriasis patients. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32:587–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1993.tb05031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gupta MA, Gupta AK. Age and gender differences in the impact of psoriasis on quality of life. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:700–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1995.tb04656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koo J. Population-based epidemiologic study of psoriasis with emphasis on quality of life assessment. Dermatol Clin. 1996;14:485–96. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8635(05)70376-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park BS, Youn JI. Factors influencing psoriasis: An analysis based upon the extent of involvement and clinical type. J Dermatol. 1998;25:97–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.1998.tb02357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blok S, Vissers WH, van Duijnhoven M, van de Kerkhof PC. Aggravation of psoriasis by infections: A constitutional trait or a variable expression? Eur J Dermatol. 2004;14:259–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Naldi L, Parazzini F, Brevi A, Peserico A, Veller Fornasa C, Grosso G, et al. Family history, smoking habits, alcohol consumption and risk of psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 1992;127:212–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1992.tb00116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fortune DG, Richards HL, Main CJ, Griffiths CE. What patients with psoriasis believe about their condition. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:196–201. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70074-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nevitt GJ, Hutchinson PE. Psoriasis in the community: Prevalence, severity and patients’ beliefs and attitudes towards the disease. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:533–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Leary CJ, Creamer D, Higgins E, Weinman J. Perceived stress, stress attributions and psychological distress in psoriasis. J Psychosom Res. 2004;57:465–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zachariae R, Zachariae H, Blomqvist K, Davidsson S, Molin L, Mørk C, et al. Self-reported stress reactivity and psoriasis-related stress of Nordic psoriasis sufferers. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:27–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2004.00721.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suljagić E, Sinanović O, Tupković E, Moro L. Stressful life events and psoriasis during the war in Bosnia. Dermatol Psychosom. 2000;1:56–60. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gupta MA, Gupta AK. The psoriasis life stress inventory: A preliminary index of psoriasis-related stress. Acta Derm Venereol. 1995;75:240–3. doi: 10.2340/0001555575240243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zachariae H, Zachariae R, Blomqvist K, Davidsson S, Molin L, Mørk C, et al. Quality of life and prevalence of arthritis reported by 5,795 members of the Nordic Psoriasis Associations: Data from the Nordic Quality of Life Study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82:108–13. doi: 10.1080/00015550252948130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Richards HL, Ray DW, Kirby B, Mason D, Plant D, Main CJ, et al. Response of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis to psychological stress in patients with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:1114–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06817.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmid-Ott G, Jacobs R, Jäger B, Klages S, Wolf J, Werfel T, et al. Stress-induced endocrine and immunological changes in psoriasis patients and healthy controls: A preliminary study. Psychother Psychosom. 1998;67:37–42. doi: 10.1159/000012257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thaller V, Vrkljan M, Hotujac L, Thakore J. The potential role of hypocortisolism in the pathophysiology of PTSD and psoriasis. Coll Antropol. 1999;23:611–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Higgins E. Alcohol, smoking, and psoriasis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2000;25:107–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2000.00588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Finlay AY, Khan GK, Luscombe DK, Salek MS. Validation of sickness impact profile and psoriasis disability index in psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 1990;123:751–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1990.tb04192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ashcroft DM, Li Wan Po A, Williams HC, Griffiths CE. Quality of life measures in psoriasis: A critical appraisal of their quality. J Clin Pharm Ther. 1998;23:391–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2710.1998.00181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feldman SR. A quantitative definition of severe psoriasis for use in clinical trials. J Dermatol Treat. 2004;15:27–9. doi: 10.1080/09546630310019382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zachariae R, Oster H, Bjerring P, Kragballe K. Effects of psychologic intervention on psoriasis: A preliminary report. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:1008–15. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(96)90280-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feldman S, Behnam SM, Behnam SE, Koo JY. Involving the patient: Impact of inflammatory skin disease and patient-focused care. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:78–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]