Abstract

The increasing recognition of occupational origin of airborne contact dermatitis has brought the focus on the variety of irritants, which can present with this typical morphological picture. At the same time, airborne allergic contact dermatitis secondary to plant antigens, especially to Compositae family, continues to be rampant in many parts of the world, especially in the Indian subcontinent. The recognition of the contactant may be difficult to ascertain and the treatment may be even more difficult. The present review focuses on the epidemiological, clinical and therapeutic issues in airborne contact dermatitis.

Keywords: Airborne contact dermatitis, occupational airborne contact dermatitis, Parthenium hysterophorus

Introduction

Airborne contact dermatitis (ABCD) is a morphological diagnosis that encompasses all acute or chronic dermatoses predominantly of exposed parts of body, which are caused by substances which when released into the air, settle on the exposed skin. Although the diagnosis of ABCD is not difficult for the trained eye, finding the causative contactant and the treatment of the resultant clinical condition may prove to be a challenge for the treating dermatologist. Contact dermatitis is designated as “airborne” on the basis of the history of the patient and the follow-up, existence of dust or of volatile causative agents, the morphology and distribution of the lesions and the results of epicutaneous tests.[1] Over the years, there has been an increasing recognition on the part of dermatologists regarding the occupational as well as the non-occupational airborne allergens and irritants. The present review is aimed at discussing the various epidemiological aspects of ABCD, the newly observed occupational and non-occupational airborne contactants, the protean clinical manifestations and the therapeutic modalities available in ABCD.

Epidemiology of Airborne Contact Dermatitis

The prevalence of ABCD is difficult to estimate. This is primarily because of the fact that it can be very difficult and cumbersome to prove an ABCD, especially of irritant type, and secondly because the term airborne has been less often used in literature. Epidemiologically, ABCD can be classified into occupational and non-occupational ABCD. It is generally believed that occupational airborne irritant contact dermatitis is grossly underreported and is much more common compared to airborne allergic contact dermatitis. Although ABCD has been reported to be caused by a number of agents, most of which have been published as case reports or small case series, majority of the data from India and outside focus largely on plant antigens as being an important cause of ABCD.

Cabanillas et al., reported a 3% prevalence of allergic dermatitis to plant antigens among patients presenting with contact dermatitis in the allergy unit, mostly in ABCD pattern.[2] Many authors have reported a significantly lower incidence and severity of sesquiterpene lactone (SL) sensitivity in East Asian population (1.4%) compared to European population (0.9–5.9%).[3–5] Mak et al., postulated that consumption of chrysanthemum since childhood in East Asia may result in induction of oral tolerance.[6] Among the patients with SL sensitivity, one third acquire it occupationally. In India, parthenium dermatitis, caused by Parthenium hysterophorus, is an important cause of ABCD.[7] It belongs to the family Compositae, subfamily Asteroide (tribe heliantheae), which itself is a large, diverse group of the plant kingdom. P. hysterophorus was accidentally introduced to India in a wheat shipment. It is a wind pollinated plant and produces an enormous quantity of pollen (up to 624 million per plant) that can be carried away in clusters of 600–800 grains. Lonkar and Jog were the first to report the epidemic of parthenium dermatitis in agriculturists and field workers at Pune, Maharashtra, in 1968.[8] Presently, it is the commonest cause of plant dermatitis in India and is responsible for 40% of patients attending contact dermatitis clinics. Today, there is increased use of herbal ingredients in culinary, cosmetic and medicinal products. Other members of the Compositae family which are in wide use are the ornamental annuals like sunflowers, cosmos, marigold, asters; herbaceous perennials like dahlia, chrysanthemum, marguerites; vegetables like lettuce, chicory, artichokes; herbal medicines like feverfew (Tanacetrim parthenium), pot marigold (Calendula); natural insecticides like pyrethrum and weeds like bindii (Soliva pterosperma), ragweed, fleabane, stinkwort and capeweed.

In a study by Agarwal et al., from South India, 50 patients with a clinical picture and history consistent with parthenium dermatitis due to exposure to P. hysterophorus were studied.[9] Ninety percent of the patients were farmers and 74.5% had exacerbations during summer. The most common type of dermatitis was the classic ABCD pattern (46%) followed by the mixed pattern (30%), erythroderma (14%) and chronic actinic dermatitis (CAD) (10%). Of the 40 patients patch tested, 90% had patch-test results positive for parthenium. In another study from Delhi, 75 patients with clinically suspected contact dermatitis were patch tested with the Indian Standard Series and indigenous antigens.[10] Parthenium was the most common contact sensitizer (20%), followed by potassium dichromate (16%), xanthium (13.3%), nickel sulfate (12%), chrysanthemum (8%), mercaptobenzothiazole and garlic (6.7% each). A study targeting regional Danish floristry gardeners and greenhouse workers determined a lifetime prevalence of almost 20% of occupational dermatitis and identified working with Compositae plants, having occupational mucosal symptoms or having a history of previous occupational eczema as the risk factors for developing occupational ABCD.[11]

Immunology of Airborne Contact Dermatitis

In airborne allergic dermatitis, initially there is a refractory phase where there is a periodic or continuous contact with allergen but no response. This is followed by an induction phase where the hapten penetrates skin, conjugates with epidermal protein, comes in contact with antigen presenting cells, migrates to draining lymph nodes followed by stimulation of naive T cells. This leads to proliferation of activated T cells to produce effector and memory cells which then enter the circulation. Re-exposure to the specific hapten leads to the release of mediators producing skin inflammation. A persistent inflammation is produced due to continued presence of effector cells. The inflammation may resolve with cellular and enzymatic degradation of antigen, inhibition of antigen presenting cells and stimulation of suppressor T cells. Akhtar et al., studied the cytokine profile in 50 patients with parthenium dermatitis, with all of them showing increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines like interleukin (IL)-6, IL-8, IL-17 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, and decreased levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines like IL-4 and IL-10.[12] A study investigating the relationship between polymorphisms of TNF and contact allergy found that the distribution of TNF-308 genotypes was significantly different between cases with contact allergy and healthy controls, with carriers of the A allele being more frequent among polysensitized patients.[13] Mahajan et al. experimentally proved that dermatitis can be caused by inhalation of allergen with interplay of type 1 and 3 hypersensitivity. Their patient showed a positive patch test to parthenium, positive delayed reaction to prick test on day 1 and histopathology showing vasculitis.[14] In contrast, Lakshmi et al. incriminated type 1 and 4 hypersensitivity in causation of ABCD due to presence of positive prick test and raised serum IgE levels in patients with patch test positive parthenium dermatitis.[15] ABCD to cedar pollen is a recently identified disease that generally affects individuals with nasal and/or ocular symptoms, as well as some patients with atopic dermatitis. It was suggested that in cedar pollinosis, PGD2-CRTH2 signaling contributes to inflammation, with the lesional skin showing IL-13, IL-18, eotaxin/chemokine (C-C motif) ligand (CCL) 11, RANTES/CCL5, macrophage-derived chemokine/CCL22 and thymus and activation-regulated chemokine/CCL17.[16]

Fillagrin mutation, as in atopic dermatitis, has been linked to causation in contact dermatitis. However, studies so far have shown conflicting results.[17] Recently, Poltromeri et al. gave the concept of occupational allergic march to describe the rapid evolution of contact dermatitis to ammonium persulfate into ABCD with rhinitis and asthma in a hairdresser.[18] The role of aeroallergens as a cause of allergic contact dermatitis or “allergic contact dermatitis like” atopic dermatitis is controversial. Inhalation of pollens, dusts, and animal hair causes either flare-up of atopic dermatitis or an apparent superimposed contact dermatitis; in some instances, the airborne allergens may produce positive patch-test reactions (i.e. with dermatophagoides).[19]

Causes of Airborne Contact Dermatitis

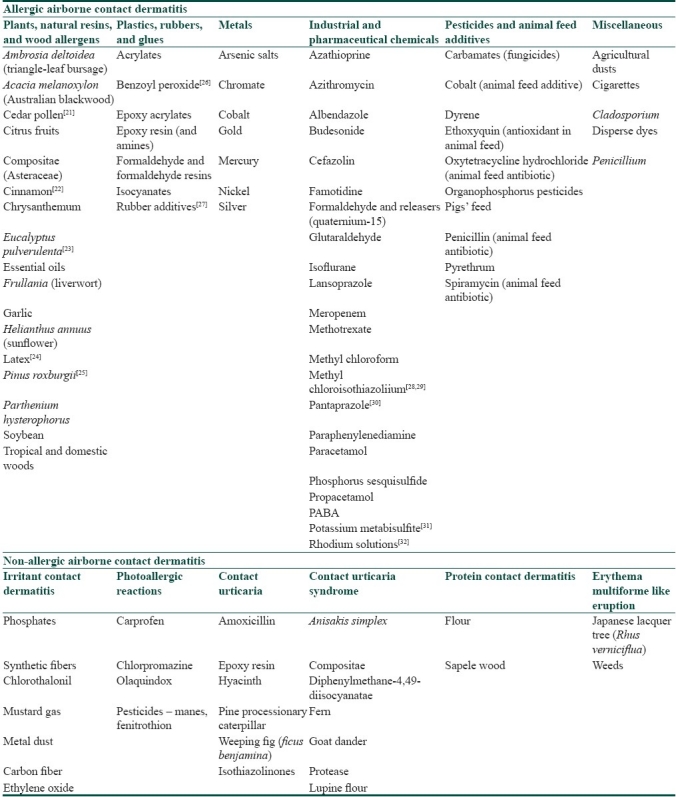

The common allergens and irritants which have been demonstrated to produce an airborne dermatitis like picture are listed in Table 1.[1,20–32] These include various acids and alkalis, metals and powders of metallic salts, cement, industrial solvents, glass fibers, sewage sludge, ammonia, vegetable and wood allergens, plastics, rubbers and glues, insecticides, pesticides, animal feed additives and many others. The airborne contactants can also be classified on the basis of their physical state as volatile airborne contactants like acids, alkalis, ammonia and pesticides; droplets like insecticides, perfumes and hair sprays; powders which include aluminum, anhydrous calcium silicate, and metallic oxides; and particles like tree sawing particles, wool and plastics.

Table 1.

Common and newer antigens which can cause airborne contact dermatitis (modified from Santos et al.[1] and Huygens et al.[20])

The most important allergens in P. hysterophorus responsible for allergic contact dermatitis are SLs, consisting of a lactone ring combined with a sesquiterpene. They are lipophilic and are present mainly in the oleoresin fraction of the plant. Parthenin, which belongs to the pseudoguinolide class of SLs, is the major allergen. It has an alpha methylene group exocyclic to gamma lactone, which is probably essential for the induction of allergy. The other allergens that have similar group are coronopilin and tetraneurin A. The other components, namely, thiopenes, monoterpenes and acetylenes, are known to cause phytophotodermatitis. SLs are also found in other genera, namely, liverwort (Frullania), tulip tree (Liriodendron, Magnoliacea) and sweetbay (Lauraceae, Laurus nobilis). Cross reaction may occur among these genera.

Clinical Presentation

A person can be sensitised to airborne contactants by direct and indirect contact, ingestion of allergens in herbal teas or exposure to herbal cosmetics. Dooms-Goossens classified airborne dermatitis into five different types, namely, airborne irritant contact dermatitis, airborne allergic contact dermatitis, airborne phototoxic reactions, airborne photoallergic reactions and airborne contact urticaria.[33] Rare presentations include acne like, lichenoid eruptions, fixed drug eruptions, exfoliative dermatitis, telengiectases, paresthesias, purpura, erythema multiforme like eruption, pellagra like dermatitis and lymphomatoid CD. Some agents cause more than one type of reaction. P. hysterophorus can produce allergic CD, photocontact dermatitis and a lichenoid eruption. Similarly, formaldehyde and phosphorus sesquisulfide can lead to an airborne irritant or allergic CD and contact urticaria.[34]

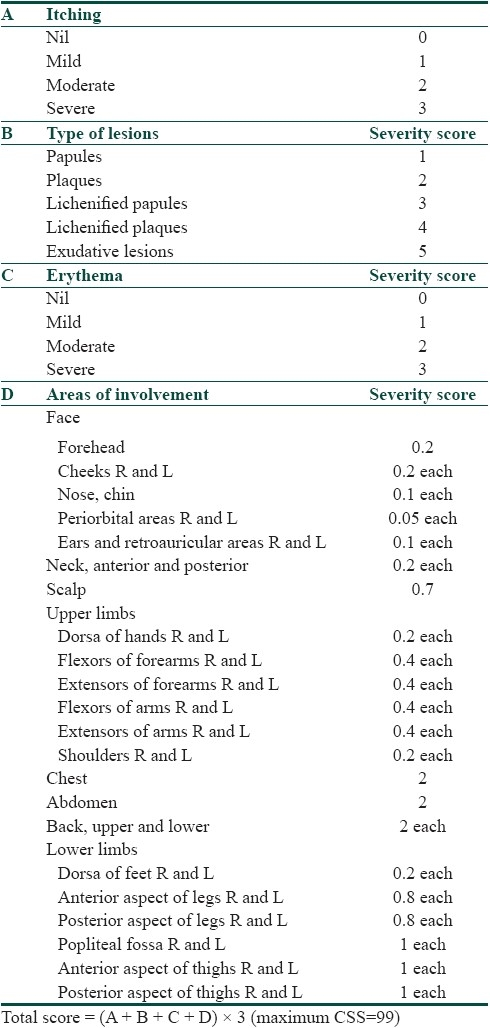

In the classical airborne allergic contact dermatitis, there is involvement of exposed areas of face, “V” of neck, hands and forearms, “Wilkinson's triangle,” both eyelids, nasolabial folds and under the chin. The involvement of both light-exposed and protected areas helps to differentiate ABCD from a photo-related dermatitis. Another close differential is atopic eczema as both ABCD and atopic eczema have predominant flexural and skin crease involvement. Initially, there is an acute flare of the dermatitis during the plant growing season but, with repeated exposure, the flare becomes prolonged and produces a chronic lichenified eczema associated with secondary infection, fissuring and hypo or hyperpigmentation. In patients wearing glasses, dermatitis occurs at the edge of nose due to occlusion. Some patients present with facial swelling before manifesting classical eczematous lesions. Severe cases show dissemination to non-exposed areas and may become erythrodermic. Verma et al., put forward a clinical severity score (CSS) to assess the severity of ABCD [Table 2].[35] It takes into consideration both the subjective features like pruritus experienced by the patient as well as the objective features like the morphology of lesions and the area involved. Airborne agents like fibrous materials (such as glass fibers, rock wool, and grain dust) give rise to mechanical dermatitis by friction due to their abrasive physical properties. Dust that contains glass fibers can produce cuts from sharp glass fragments, and asbestos “corns” may be seen on palmer aspect of fingers on exposure to spicules of asbestos. A lichenified dermatitis may be produced by wood and cement dust collecting around the collar, belt line, or sleeve end and other points of contact. Dust may also cause irritant dermatitis with clinical appearance of folliculitis.[36]

Table 2.

Clinical severity score to assess severity of ABCD (adapted from Verma et al.[35])

Alternatively, ABCD can be subclassified into that of plant origin and non-plant origin. Wood and plants are a rich source of airborne allergens and irritants, the causative agent often being the dried botanical material. The most commonly seen parthenium dermatitis classically presents as ABCD but may occasionally present with photosensitive lichenoid eruption in morphology and distribution. Rarely, the disease may present as photocontact dermatitis or actinic reticuloid syndrome.[37] Few case reports of prurigo nodularis like lesions have been reported.[38] Occupational type I Compositae allergy is rarely reported because few people are tested. ABCD sparing vitiliginous skin has been reported from India.[39] A study observing the evolution of parthenium dermatitis recruited 74 patients who were classified into ABCD, CAD pattern or mixed pattern dermatitis. Sixty patients had ABCD, five had mixed pattern and nine had CAD pattern at the onset. Of the 60 patients with ABCD, 27 changed to CAD pattern and 11 to mixed pattern after an average period of 4.2 years. Additionally, sawdust from teak, redwood, mahogany, and rosewood may contain sensitizers that produce a dry dermatitis, particularly on the face, penis, and scrotum in carpenters and woodworkers.[40] Dermatitis of woodworkers may be caused also by liverworts (SLs) and lichens (usnic acid or atranorin) found on the bark of trees.[41,42] The allergy can also be derived from the smoke of burning plants.

Cement dust usually presents as a dry, lichenified dermatitis due to its alkaline and hygroscopic properties. The eruption tends be dry rather than oozy even in cases of allergic contact dermatitis to the chromium or cobalt content in cement. Genital dermatitis due to indirect hand contact and accumulation of sawdust on the clothes is often seen in cabinet makers. Dermatitis from vapors is usually of occupational origin. In these cases, amines used as epoxy hardeners and resins are the most common culprits.[43] Turpentine used to be the most frequent cause of airborne dermatitis, but is seen rarely now. Polyolefins, when heated, degrade and form aldehydes, ketones, and acids and very rarely induce airborne dermatitis.[44] Additionally, plastic, rubber, glues, metals, insecticides, pesticides, solvents, and other industrial and pharmaceutical chemicals have been described as causing airborne dermatitis.

Diagnosis of ABCD

While managing ABCD, care must be taken to distinguish between occupational and non-occupational disease and between irritant and allergic occupational ABCD, as management will differ. A temporal correlation with work only raises the suspicion which needs to be confirmed with patch test or prick test. In suspected cases of occupational irritant dermatitis, the responsible agent may be isolated by means of chemical analysis or direct microscopic study of the air or material in the air. The patch test is used to find out causative allergens. Photopatch tests can be useful for excluding light as a factor in the pathogenesis of the lesions. During patch testing, volatile allergens sometimes also cause irritant dermatitis; therefore, high dilutions should be used. Sometimes special glass cups which permit exposure to the vapor of allergen have to be used. For testing wood dust, it should not be moistened as it increases irritancy.

SL mix 0.1% petrolatum is commercially available and consists of equimolar quantities of three pure SLs (alantolactone, dehydrocostus lactone and costunolide). In a study, only 35% of cases of Compositae allergy were detected by using only SL mix and it was concluded that SL mix was not an adequate screening test. The SL mix failed to detect 38% of Compositae-sensitive patients.[45] These patients can be identified by using additional Compositae extracts like dandelion or feverfew extracts when there is a clinical suspicion of Compositae allergy. Another study comparing Compositae mix with SL mix was done in which Compositae mix led to few irritant reactions and less false-negative test results as compared to SL mix.[46] It was concluded that Compositae dermatitis is being underdiagnosed and that the Compositae mix is significantly more sensitive in detecting Compositae allergy than the SL mix.

Treatment of ABCD

Treatment of ABCD is difficult, with great emphasis on individualization. Severity of contact dermatitis depends upon degree of contact hypersensitivity and quantity of antigen to which the patient is exposed. For effective control of dermatitis, these two factors should be reduced. As the hypersensitivity is difficult to be reduced, the only option is to reduce quantity of antigen to which patient is exposed. Substitution reduces the incidence of occupational dermatitis and urticaria. In cases of ABCD due to parthenium, one should avoid going outdoors on days when pollen are present in high concentrations in air, especially in summers and in the months from September to November following the north-east monsoon showers. Air conditioning decreases indoor pollen counts. Simple routines like taking a bath after coming indoors; wearing fresh clothes and eliminating weeds and grasses in the house garden can offer great help. Use of a barrier cream on the exposed areas after every wash is important to slow down penetration of antigen into skin. Other measures which can be used are photoprotection, sunscreens, change of job, change of residence, antihistamines, drying agents in cases of weeping eruptions, aluminum sulfate and calcium acetate and emollients for lichenified areas, etc.[47]

Topical steroids are the mainstay of therapy as in other eczemas. They decrease the number of HLA DR+ Langerhans cells and inhibit the production and function of IL-1, IL-2 and interferon (IFN)-γ. Systemic steroids decrease T cell proliferation and are indicated when there is more than 25% body surface area involvement and when dermatitis is suspected to be caused by allergens which persist in the skin for weeks after exposure (Toxicodendron oleoresins). Psoralens and UVA (PUVA) decreases HLA DR+ Langerhans cells [LC], whereas UVB induces epidermal hyperplasia and PGE. Immunosuppressives are indicated for severe, recalcitrant and photosensitive dermatitis–actinic reticuloid patient. The most commonly used immunosuppressive agent is azathioprine. It blocks DNA replication by incorporating 6-thioguanine into DNA and prevents lymphocytic proliferation after antigenic stimulation.[48] Both the number and antigen presenting capacity of LC are affected. In a study, azathioprine weekly pulses were given to patients with chronic lichenified eczema.[35] The response was excellent (80–100% clearance of disease) in 58.3% patients and good (60% clearance) in 41.7% patients. There were no significant side effects of the therapy. The cost of therapy with this regimen was reduced by 60%.[49] In another therapeutic study on patients of parthenium dermatitis, three therapeutic regimens with azathioprine were used.[50] A total of 22 patients (group I) were given 50 mg azathioprine twice a day, 11 patients (group II) received 50 mg azathioprine per day and 300 mg azathioprine every 28 days, and 10 patients (group III) were given 50 mg azathioprine twice a day along with 300 mg azathioprine every 28 days. The duration of treatment varied from 6 months to 3 years. Twenty out of 22 in group I and 9/11 patients in group II and 9/10 patients in group III had complete remission. Nine out of 22, 7/11 and 6/10 patients in the respective groups needed additional oral betamethasone 1–2 mg per day for brief periods only during the peak season in order to maintain complete remission. Sharma et al., treated 16 patients with parthenium dermatitis, unresponsive to topical treatment, with oral methotrexate (15 mg/week). Clinical response was monitored using a dermatitis area and severity index. Seven patients completed 6 months or more of follow-up, and their mean DASI fell to 5, 2.7 and 2.1 at the end of 1, 3 and 6 months, respectively, from a baseline score of 10. Only 3/7 patients required oral prednisolone in the initial 2–4 weeks.

Hyposensitization refers to introduction of an antigen into the body by a route different from the natural one, to induce such a change in the immune system that the body does not develop clinical manifestations when the antigen is introduced into the body through normal route.[51] Oral hyposensitization, although demonstrated to be effective for ragweed dermatitis, has not been widely accepted because it carries considerable risk of provoking and worsening eczema. In some cases, patients are co-sensitized with several unrelated pollen allergens. Based on frequent co-sensitization patterns, some of the hybrid proteins have been developed with the polymerase chain reaction. These hybrids contain all the epitopes from the different allergen in a single protein. These have been used for vaccination against pollen allergy. Antibodies induced with the hybrids in mice inhibited the binding of grass pollen-allergic patients’ immunoglobulin E to each of the individual allergens and grass pollen extract, and may thus represent protective antibodies. Handa et al., evaluated the effect of oral hyposensitization as an alternative therapeutic modality and observed a gradual improvement in the clinical status of 70% of those patients who completed the study, as evident from a fall in their clinical severity score for eczema. The treatment had to be stopped in 30% of patients as they experienced an exacerbation during the course of the study. Overall, patients tolerated the therapy well and no significant side effects were seen, except for abdominal pain, “heartburn” and cheilitis.[52]

Conclusions

Evidence indicates that up to 50% of patients with ABCD, whether occupational or non-occupational, experience adverse effects on quality of life, daily function and personal relationship, and take time off work on sick leave and may lose or change job because of their skin disease.[46] A significant proportion of patients still tend to have active symptoms many years after diagnosis, despite treatment and change of job. However, it should be emphasized to all that avoidance of further exposure can lead to recovery from dermatitis in many cases. With respect to ABCD occurring secondary to parthenium dermatitis, there are continuing attempts to control the spread of the weed through biological measures like introduction of exotic arthropods and opportunistic pathogens, use of antagonistic plants and bioherbicides as well as use of selective chemical herbicides.

Footnotes

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Santos R, Goossens AR. An update on airborne contact dermatitis: 2001–2006. Contact Dermatitis. 2007;57:353–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.2007.01233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cabanillas M, Fernández-Redondo V, Toribio J. Allergic contact dermatitis to plants in a Spanish dermatology department: A 7-year review. Contact Dermatitis. 2006;55:84–91. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-1873.2006.00888.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Du P, Menage H, Hawk JL, White IR. Sesquiterpene lactone mix contact sensitivity and its relationship to chronic actinic dermatitis: A follow-up study. Contact Dermatitis. 1998;39:119–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1998.tb05859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geier J, Hausen BM. Epikutantestung mit dem Kompositen-Mix. Ergebnisse eider Studie der Deutschen Kontaktallergie-Gruppe (DKG) einer-Informationsverbundes Dermatologischer Kliniken (IVDK) Allergologie. 2000;25:334–41. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tan E, Leow YH, Ng SK, Goh CL. A study of the sensitization rate to sesquiterpene lactone mix in Singapore. Contact Dermatitis. 1999;41:80–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1999.tb06230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mak RK, White IR, White JM, McFadden JP, Goon AJ. Lower incidence of sesquiterpene lactone sensitivity in a population in Asia versus a population in Europe: An effect of chrysanthemum tea? Contact Dermatitis. 2007;57:163–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.2007.01117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharma VK, Sethuraman G, Tejasvi T. Comparison of patch test contact sensitivity acetone and aqueous extracts of Parthenium hysterophorus in patients with airborne contact dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 2004;50:230–2. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-1873.2004.0318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lonkar A, Jog MK. Dermatitis caused by plant Parthenium hysterophorus: A case report. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1968;34:194–6. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agarwal KK, Souza MD. Airborne contact dermatitis induced by parthenium: A study of 50 cases in South India. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:e4–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2008.02960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singhal V, Reddy BS. Common contact sensitizers in Delhi. J Dermatol. 2000;27:440–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2000.tb02202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dickel H, Leiste A, Tran DH, Stücker M, Altmeyer P. “Spring-summer-fall dermatitis” in a florist. Consequences for workmen's compensation insurance. Hautarzt. 2008;59:922–8. doi: 10.1007/s00105-008-1495-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akhtar N, Verma KK, Sharma A. Study of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine profile in the patients with parthenium dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 2010;63:203–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.2009.01693.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Westphal GA, Schnuch A, Moessner R, Koenig IR, Kränke B, Hallier E, et al. Cytokine gene polymorphisms in allergic contact dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 2003;48:93–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0536.2003.480208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mahajan VK, Sharma NL, Sharma RC. Parthenium dermatitis: Is it a systemic contact dermatitis or an airborne contact dermatitis? Contact Dermatitis. 2004;51:231–4. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-1873.2004.00400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lakshmi C, Srinivas CR. Parthenium dermatitis caused by immediate and delayed hypersensitivity. Contact Dermatitis. 2007;57:64–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.2007.01145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oiwa M, Satoh T, Watanabe M, Niwa H, Hirai H, Nakamura M, et al. CRTH2-dependent, STAT6-independent induction of cedar pollen dermatitis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2008;38:1357–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2008.03007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schnuch A, Westphal G, Mössner R, Uter W, Reich K. Genetic factors in contact allergy—review and future goals. Contact Dermatitis. 2011;64:2–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.2010.01800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Poltronieri A, Patrini L, Pigatto P, Riboldi L, Marsili C, Previdi M, et al. Occupational allergic “march”. Rapid evolution of contact dermatitis to ammonium persulfate into airborne contact dermatitis with rhinitis and asthma in a hairdresser. Med Lav. 2010;101:403–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clark RA, Adinoff AD. Aeroallergen contact can exacerbate atopic dermatitis: Patch test as a diagnostic tool. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21:8639. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(89)70269-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huygen S, Goossen A. An update on airborne contact dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 2001;44:1–6. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0536.2001.440101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yokozeki H, Satoh T, Katayama I, Nishioka K. Airborne contact dermatitis due to Japanese cedar pollen. Contact Dermatitis. 2007;56:224–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.2004.00491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ackermann L, Aalto-Korte K, Jolanki R, Alanko K. Occupational allergic contact dermatitis from cinnamon including one case from airborne exposure. Contact Dermatitis. 2009;60:96–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.2008.01486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paulsen E, Larsen FS, Christensen LP, Andersen KE. Airborne contact dermatitis from Eucalyptus pulverulenta ‘Baby Blue’ in a florist. Contact Dermatitis. 2008;59:171–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.2008.01357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Proietti L, Gueli G, Bella R, Vasta N, Bonanno G. Airbone contact dermatitis caused by latex exposure: A clinical case. Clin Ter. 2006;157:341–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mahajan VK, Sharma NL. Occupational airborne contact dermatitis caused by Pinus roxburghii sawdust. Contact Dermatitis. 2011;64:110–1. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.2010.01836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lammintausta K, Neuvonen H. Airborne allergic contact dermatitis from 4-(bromomethyl)benzoic acid in a university chemist. Contact Dermatitis. 2008;58:314–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.2007.01293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giorgini S, Martinelli C, D’Erme AM, Lotti TM. A case of airborne allergic contact dermatitis by rubber additives. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2010;145:133–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hunter KJ, Shelley JC, Haworth AE. Airborne allergic contact dermatitis to methylchloroisothiazolinone/methylisothiazolinone in ironing water. Contact Dermatitis. 2008;58:183–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.2007.01240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jensen JM, Harde V, Brasch J. Airborne contact dermatitis to methylchloroisothiazolinone/ methylisothiazolinone in a boy. Contact Dermatitis. 2006;55:311. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.2006.00818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neumark M, Ingber A, Levin M, Slodownik D. Occupational airborne contact dermatitis caused by pantoprazole. Contact Dermatitis. 2011;64:60–1. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.2010.01783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stingeni L, Bianchi L, Lisi P. Occupational airborne allergic contact dermatitis from potassium metabisulfite. Contact Dermatitis. 2009;60:52–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.2008.01450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goossens A, Cattaert N, Nemery B, Boey L, De Graef E. Occupational allergic contact dermatitis caused by rhodium solutions. Contact Dermatitis. 2011;64:158–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.2010.01808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lotti T, Menchini G, Teofoli P. The Challenge of Airborne Dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 1998;16:27–31. doi: 10.1016/s0738-081x(97)00168-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dooms-Goosens A, Deleu H. Airborne contact dermatitis: An update. Contact Dermatitis. 1991;25:211–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1991.tb01847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Verma KK, Manchanda Y, Pasricha JS. Azathioprine as a corticosteroid sparing agent for the treatment of dermatitis caused by the weed Parthenium. Acta Derm Venereol. 2000;80:31–2. doi: 10.1080/000155500750012487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dooms-Goossens A, Debusschere KM, Gevers DM. Contact dermatitis caused by airborne agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;15:1–100. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(86)70135-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sharma VK, Sethuraman G. Parthenium dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2007;18:183–90. doi: 10.2310/6620.2007.06003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sharma VK, Sahoo B. Prurigo nodularis like lesions in parthenium dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 2000;42:235. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0536.2000.042004235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Singh KK, Srinivas CR, Balachandran C, Menon S. Parthenium dermatitis sparing vitiliginous skin. Contact Dermatitis. 1987;16:74. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1987.tb01415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sharma VK, Sethuraman G, Bhat R. Evaluation of clinical patterns of Parthenium dermatitis: A study of 74 cases. Contact Dermatitis. 2005;44:49–50. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-1873.2005.00652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Foussereau J, Benezra L, Maibach HI. Occupational contact dermatitis. Copenhagen: Munksgaard; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thune P. Contact allergy due to lichens in patients with a history of photosensivity. Contact Dermatitis. 1977;3:267–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1977.tb03673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dahlquist I, Fregert S. Allergic contact dermatitis from volatile epoxy hardeners and reactive diluents. Contact Dermatitis. 1979;5:406–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1979.tb04920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bjorkner B. Plastic materials. In: Rycroft RJ, Menn T, Frosch PJ, editors. Textbook of contact dermatitis. 2nd ed. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Verlag; 1992. p. 563. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Green C, Ferguson J. Sesquiterpene lactone mix is not an adequate screen for Compositae allergy. Contact Dermatitis. 1994;31:151–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1994.tb01954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Paulsen E, Andersen KE, Hausen BM. An 8-year experience with routine SL mix patch testing supplemented with Compositae mix in Denmark. Contact Dermatitis. 2001;45:29–35. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0536.2001.045001029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nicholson PJ, Llewellyn D, English JS. On behalf of the Guidelines Development Group. Evidence-based guidelines for the prevention, identification and management of occupational contact dermatitis and urticaria. Contact Dermatitis. 2010;63:177–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.2010.01763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Patel AA, Swerlick RA, McCall CO. Azathioprine in dermatology: The past, the present, and the future. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:369–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.07.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Verma KK, Bansal A, Sethuraman G. Parthenium dermatitis treated with azathioprine weekly pulse doses. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2006;72:24–7. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.19713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sharma VK, Bhat R, Sethuraman G, Manchanda Y. Treatment of parthenium dermatitis with methotrexate. Contact Dermatitis. 2007;57:118–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.2006.00950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Srinivas CR, Krupashankar DS, Singh KK. Oral hyposensitisation in parthenium dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 1988;18:242–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1988.tb02814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Handa S, Sahoo B, Sharma VK. Oral hyposensitisation in patients with contact dermatitis from Parthenium hysterophorus. Contact Dermatitis. 2001;44:279–82. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0536.2001.440505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]