Abstract

An elderly man from the region of Ladakh presented with recurrent episodes of lower respiratory tract infection, rapidly progressive Acanthosis nigricans, Acanthosis palmaris and plantar keratoderma. Detailed investigations revealed underlying metastatic transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. This case is being reported for its rarity in the literature.

Keywords: Acanthosis nigricans, acanthosis palmaris, plantarkeratoderma, transitional cell carcinoma

Introduction

Acanthosis nigricans (AN) is a dermatological condition characterized by symmetric, hyperpigmented, hyperkeratotic, verrucous plaques that bestow a velvety texture on intertriginous skin and occasionally mucocutaneous areas.[1] First independently described by Pollitzer-Janovsky in 1891, the term “Acanthosis nigricans” was first proposed by Unna, Acanthus, from the Greek, meaning “thorn” and nigricans, from the Latin, meaning “becoming black”.[2] Based on clinical characteristics Schwartz divided AN into eight types: benign AN, pseudo Acanthosis nigricans connected with obesity, syndromic AN, paraneoplastic, malignant AN, acral AN, unilateral AN, drug-induced AN and mixed AN.[3] Malignant AN, a type of paraneoplastic syndrome, an uncommon condition, generally has a poor prognosis with low survival rate.[3] Here we report a 70-year-old man with rapidly progressive AN, Acanthosis palmaris and plantarkeratoderma in association with metastatic transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder.

Case Report

A 70-year-old Ladakhi farmer presented with a history of progressive darkening and thickening of skin over the flexural areas, associated with pruritus of one month's duration. The lesions appeared initially on the nape of the neck, rapidly spreading to involve the axillae, hips, gluteal regions, dorsum of knees, lower legs and dorsum of both hands and feet. There was history of recurrent cough, fever and breathlessness of six months’ duration which was managed at another centre with oral antibiotics and inhaled beta-2 agonists. There was no history of anorexia, vomiting, weight loss, hematemesis, melena, orthopnea, swelling of face or feet, chest pain, pain abdomen, hematuria, dysuria, or low backache. There was no history of drug intake or endocrine abnormalities. The family members were unaffected. He was a smoker for the last 30 years, consuming 10-15 bidis (non-filtered cigarettes) daily.

His weight was 70 kg with a BMI of 22.59 kg/m2. Vital parameters were normal. He had mild pallor but no icterus, cyanosis, clubbing or pedal edema. He had extensive non-tender cervical lymphadenopathy, with the largest node measuring 4 cm × 5 cm in the left cervical region. The overlying skin was normal. Examination of the respiratory system revealed rhonchi over both lung fields. The rest of the systemic examination was normal.

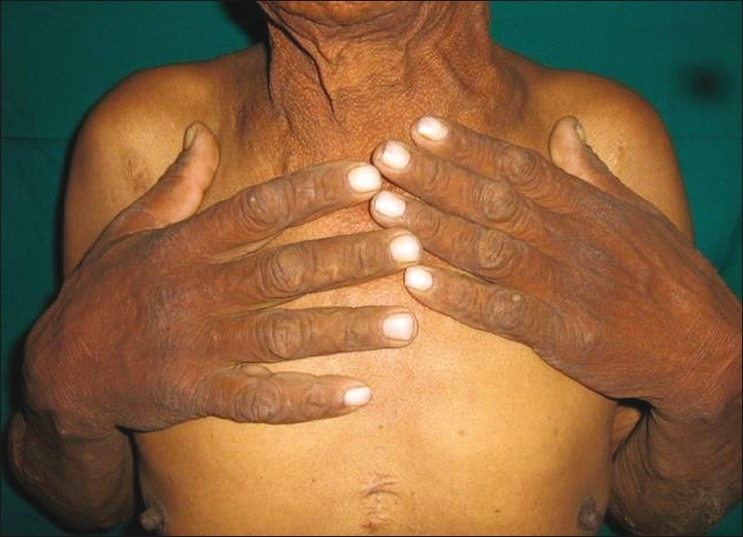

Dermatological examination revealed velvety skin with black discoloration over both axillae, nape of the neck, dorsum of both knees, and dorsum of both hands and feet. There were multiple small acrocodons in both axillae. Bilateral plantar hyperkeratosis with fissuring of the heels was present. Both palms were also hyperkeratotic [Figures 1 and 2].

Figure 1a.

Acanthosis nigricans on the nape of the neck and axilla

Figure 2a.

Acanthosis palmaris and plantar keratoderma

Figure 1b.

Acanthosis nigricans on the nape of the neck and axilla

Figure 2b.

Acanthosis palmaris and plantar keratoderma

Investigations revealed normocytic hypochromic anemia (hemoglobin 8.7 g/ dl), raised erythrocyte segmentation rate (10 mm/1st h) and raised total leucocyte count (11800/cmm). Urine was turbid, acidic in reaction with proteins in plenty, numerous neutrophils and red blood cell, 3-4 epithelial cells and granular casts. Urine culture did not show any growth after 24 h. Stool occult blood was negative. Chest X-ray showed multiple metastases in both lung fields [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Chest radiograph showed multiple sharply circumscribed nodules of variable size scattered in both lung fields, suggestive of metastasis

Fine needle aspiration cytology from the cervical lymph nodes revealed malignant aspirate suggestive of metastasis from thyroid/gastrointestinal tract/bladder/kidney. A subsequent contrast-enhanced computed topography (CT) scan of the abdomen revealed multiple polypoidal enhancing mass lesions with surface calcifications within the urinary bladder. There was no extravesical extension and no pelvic lymphadenopathy. However, there were multiple enlarged paraaortic and retrocrural lymph nodes. Incidentally, the left kidney was detected to be small in size. A diagnosis of bladder cancer with pulmonary metastasis and retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy (Jewett Strong Stage D2) was made [Figure 4]. Biopsy from the bladder mass revealed transitional cell carcinoma [Figure 5]. Carcinoembryonic antigen showed a 30fold increase.

Figure 4.

Axial CT images showing multiple polypoidal enhancing mass lesions with surface calcifications, in the urinary bladder

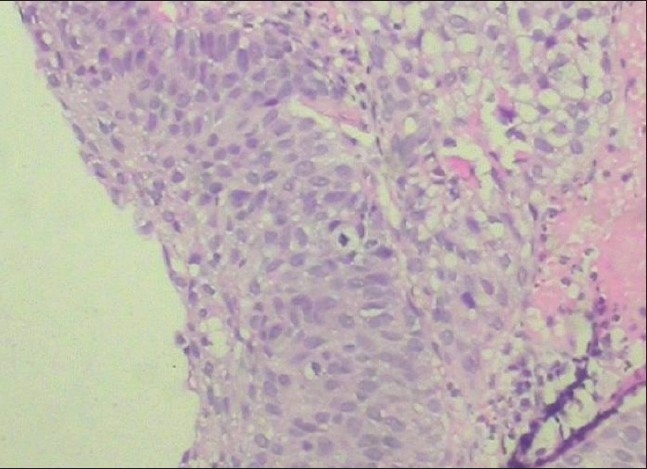

Figure 5.

Histological section of the specimen of tumor taken by transurethral biopsy from the urinary bladder. The specimen shows transitional cell carcinoma (hematoxylin and eosin, magnification ×450)

Discussion

Malignant AN is a rare, rapidly progressive form of AN, usually seen in the elderly; however, rapidly progressive AN in an adult is almost 100% associated with internal malignancies.[4] In one study, only 2 of 12,000 patients with cancer had signs of AN. The most frequent associations were with adenocarcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract (70-90%), particularly gastric cancer (55-61% of malignant AN cases). This condition is co-diagnosed with the cancer in 61.3%; whereas in 17.6% cases it predates the diagnosis of malignancy.[5] Acanthosis nigricans is likely caused by factors that stimulate epidermal keratinocyte and dermal fibroblast proliferation. In the benign form, the factor is probably insulin or an insulin-like growth factor (IGF) that incites the epidermal cell propagation. Other proposed mediators include other tyrosine kinase receptors, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) or fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR). In malignant AN, the stimulating factor is hypothesized to be a substance secreted either by the tumor or in response to the tumor. Transforming growth factor (TGF)–alpha is structurally similar to epidermal growth factor and is a likely candidate.[6] Histologically, there is no difference between the benign and malignant form.[7] Paraneoplastic AN can occur in three abortive clinical subforms as papillomatosis florida cutis verruciformis, tripe palmar syndrome and Leser Trélat sign. They coexist together or appear consecutively after each other.[8] The occurrence of AN is rarely reported in urological cancers such as renal cell carcinoma, bladder carcinoma and prostatic carcinoma, and seems to be an indicator of a bad prognosis.[9,10]

Our patient had all the typical features of AN along with Acanthosis palmaris and plantar keratoderma; however, he was completely asymptomatic despite the extensive AN and widespread metastases. The standard recommended regimen for metastatic muscle-invasive bladder cancer is M-VAC (methotrexate, vinblastine, adriamycin and cisplatin) and gemcitabine.[11] The patient was referred to an oncology centre and considering his age and the advanced disease offered palliative therapy. For his dermatological condition, he was advised emollients, keratolytics and topical retinoids, to which he responded minimally.

Our case highlights that rapid-onset AN along with Acanthosis palmaris and plantar keratoderma in an asymptomatic elderly person requires a thorough clinical examination and extensive multi-modality investigations to rule out underlying malignancy. The primary malignancy in our patient was transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder. To our knowledge there are only a few cases in the literature.[12] However, no such case has been reported from India.

Acknowledgments

Maj V Uppal and Maj PS Mishra, Pathologists (153 General Hospital and Base Hospital Lucknow, respectively)

Footnotes

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.De Witt CA, Buescher LS, Stone SP. Cutaneous manifestations of internal malignant disease: Cutaneous paraneoplastic syndromes. In: Wolf K, Lowell A, editors. Fitzpatric's dermatology in general medicine. 7th ed. Vol. 2. New York: McGraw Hill publication; 2008. pp. 1493–96. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pollitzer S. Acanthosis nigricans. In: Unna PG, Morris M, Besnier E, editors. Internal Atlas of Rare Skin Diseases. London, UK: Lewis and Co; 1891. pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwartz RA. Acanthosis nigricans. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:1–19. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(94)70128-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thiers BH, Sahn RE, Callen JP. Cutaneous manifestations of internal malignancy. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:73–98. doi: 10.3322/caac.20005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krawczyk M, Mykala-Ciesla J, Kolodziej-Jaskula A. Acanthosis nigricans as a paraneoplastic syndrome. Case reports and review of literature. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2009;119:180–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Torley D, Bellus GA, Munro CS. Genes, growth factors and Acanthosis nigricans. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:1096–101. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.05150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyce S, Harper J. Paraneoplastic dermatoses. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20:523–32. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8635(02)00015-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sacco E, Pinto F, Sasso F, Racioppi M, Gulino G, Volpe A, et al. Paraneoplastic syndromes in patients with urological malignancies. Urol Int. 2009;83:1–11. doi: 10.1159/000224860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moscardi JL, Macedo NA, Espasandin JA, Piñeyro MI. Malignant Acanthosis nigricans associated with a renal tumor. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32:893–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1993.tb01410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Möhrenschlager M, Vocks E, Wessner DB, Nährig J, Ring J. Tripe palms and malignant Acanthosis nigricans: Cutaneous signs of imminent metastasis in bladder cancer? J Urol. 2001;165:1629–30. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(05)66369-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Puppo P, Conti G, Francesca F, Mandressi A, Naselli A. New Italian guidelines on bladder cancer, based on the World Health Organization 2004 classification. BJU Int. 2010;106:168–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gohji K, Hasunuma Y, Gotoh A, Shimogaki H, Kamidono S. Acanthosis nigricans associated with transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Int J Dermatol. 1994;33:433–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1994.tb04046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]