Abstract

Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) inhibitors, such as etanercept, infliximab, and adalimumab, bind to TNF-α and thereby act as anti-inflammatory agents. This group of drugs has been approved for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, ankylosing spodylitis, Crohn disease, and juvenile idiopathic arthritis. We describe a 56-year-old woman who developed an erythematous pruritic rash on both arms—diagnosed as granuloma annulare by skin biopsy—approximately 22 months after initiating adalimumab for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. On stopping adalimumab there was total clearance of the skin lesions, but a similar rash developed again when her treatment was switched to another anti-TNF agent (etanercept). This clinical observation supports a link between TNF inhibition and the development of granuloma annulare.

Keywords: Adverse effect, anti-TNF therapy, granuloma annulare

Introduction

Anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) agents have provided a new dimension to the treatment of both cutaneous and systemic inflammatory diseases. Clinicians have been using these agents for almost 15 years with great success. However, a challenging paradox is that, on rare occasions, anti-TNF agents can induce various autoimmune diseases.[1–3] Here we report a very rare phenomenon: the appearance of disseminated granuloma annulare (GA) following therapy with adalimumab; this disappeared after stopping the drug but relapsed at the same sites on restarting treatment with etanercept, another anti-TNF agent. Thus, appearance of GA following treatment with anti-TNF agent appears to be a class effect rather than a response to a specific anti-TNF agent.

Case Report

A 56-year-old woman with history of hepatitis C genotype 2a, low viral load, and osteoporosis presented to our rheumatology clinic in February 2008 for pain and swelling of the third proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints and ankles on both sides. There were no skin findings. Laboratory investigations (done in 2007) indicated that rheumatoid factor was positive, while antinuclear antibody (ANA), anti-DNA, and SCL-70 were negative. Repeat laboratory tests in February 2008 were notable for elevated IgG, normal C3 and C4, negative anti-SSA, and reactive hepatitis C antibody. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the left wrist showed inflammatory flexor and extensor tenosynovitis and a focal erosion of the capitate. MRI of the right wrist showed tenosynovitis of the extensor tendons and a small erosion of the head of the fifth metatarsal. Although the patient presented with an oligoarthritis, she was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis, as she had the classic erosive changes in association with a positive rheumatoid factor. Due to her hepatitis C status, she was started on plaquenil 200 mg twice daily.

On her follow-up visit in June 2008, her symptoms had improved slightly with plaquenil, but she continued to have dysfunction in her hands. After discussion with the patient, adalimumab 40 mg every other week was instituted, while plaquenil 200 mg b.i.d. was continued. The patient's yearly PPDs had been negative.

In January 2009, the patient reported marked improvement of her arthritis. She was able to carry out her daily activities, with reduced pain and morning stiffness. Treatment with adalimumab 40 mg every other week was continued. She continued to do well until April 2010, when she complained of development of ‘hives’ on her arms, which were not relieved by antihistamines. Examination of her rash by her primary physician in the beginning of May 2010 had revealed soft, nontender papules of 1 cm, with no underlying erythema, along with smaller 2–4 mm papules with small punctate area on the both forearms. She was prescribed daily cetirizine but 3 days later the pruritic rash had spread to cover most of her forearms.

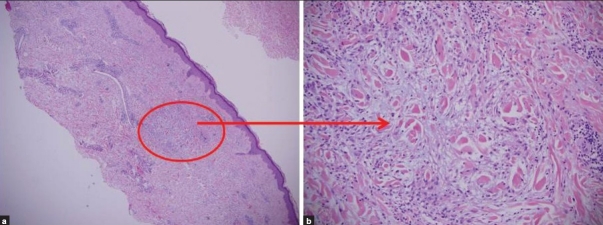

Adalimumab was discontinued on June 8, 2010, by the patient's rheumatologist. However, she continued to have discrete urticarial papules on her arms. She started having increased joint pains, which were then only being treated with plaquenil. Laboratory results at that time indicated positive ANA (1:640), diffuse pattern, anti-DNA 1:640 with negative/normal anti-SSA, anti-SSB, C3 and C4. The patient was started on prednisone 10 mg daily along with fexofenadine 180 mg daily. A skin biopsy from the right forearm revealed a palisading infiltrate of histiocytes and lymphocytes in the dermis, with surrounding paucicellular zones containing altered collagen fibers and increased mucin; the picture was diagnostic of GA [Figure 1]. By July 2010, the patient's rash had resolved with prednisone 10 mg and fexofenadine 180 mg daily and these medicines were therefore discontinued. At this time she had severe arthritis and after discussion with the patient we restarted treatment, this time with etanercept 50 mg weekly. In the beginning of August 2010, her rash relapsed with similar morphology at the same sites as the previous GA attack, and she developed generalized pruritus. Etanercept was discontinued and the patient was treated with prednisone 15 mg/daily plus fexofenadine. Her cutaneous symptoms resolved over the next 2 weeks.

Figure 1.

Palisading granuloma (hematoxylin and eosin stain): (a) multiple granulomas, consisting of lymphomononuclear cells in the dermis around small foci of degenerated collagen (×4); (b) a central core of degenerated collagen surrounded by a radially arranged infiltrate of lymphomononuclear cells (×20)

Discussion

GA is usually a self-limiting skin disorder that presents as arciform to annular papules and mainly affects children and adults under 30 years of age. Women are twice as likely to be affected as men. The different types of GA include the localized, generalized, subcutaneous, perforating, and patch forms, and it typically involve the hands, arms, forearms, legs, and feet. GA has been associated with trauma, some medications, diabetes mellitus, tuberculosis, thyroid diseases, and malignancies. It is also believed that there is some association between GA and some infectious agents, e.g., human immunodeficiency virus, Epstein–Barr virus, and hepatitis C virus.

TNF-α inhibitors are highly effective for the treatment of various systemic and cutaneous autoimmune diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, ankylosing spondylitis, Crohn disease, and juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Despite the good overall efficacy of these biologic agents, they can also rarely induce a number of autoimmune diseases, including new-onset psoriasis, skin vasculitis, and systemic lupus erythematosus.[1–3] These conditions may be reversible upon discontinuation of the medication.

A variety of cutaneous reactions have been reported following the use of anti–TNF-α agents.[4] The most common cutaneous side effects are injection site reactions. There are a few reports suggesting that disseminated GA could be a unique adverse effect of anti-TNF preparations.[5,6] In one report, in a cohort of 199 rheumatoid arthritis patients, 9 subjects were found to develop GA following anti–TNF-α therapy.[5] Two were treated with infliximab, six with adalimumab, and one with etanercept. The majority of these patients developed erythematous skin eruptions over the fingers, hands, and arms, consistent with the generalized type of GA. The diagnosis in these cases was confirmed by skin biopsy.[5] Interestingly, there are case reports of disseminated recalcitrant GA successfully treated with infliximab.[7,8]

Our patient followed a similar course as has been described earlier in rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with anti-TNF agents.[5] Although she had been diagnosed with hepatitis C approximately 15 years ago, her viral load had been low and she had never developed any skin condition consistent with GA prior to initiation of TNF-α inhibitors. Furthermore, complete resolution of GA following discontinuation of anti-TNF agents suggests that hepatitis C is unlikely to be the cause of GA in this patient. She had neither been diagnosed with any other disease nor received any medications known to be associated with GA. Her GA resolved with the discontinuation of the anti-TNF agent (adalimumab) and reappeared on initiation of treatment with another class of anti-TNF agent (etanercept), suggesting that induction of GA is the result of TNF inhibition as such rather than a reactive response to any specific anti-TNF agent. To conclude, GA could be a rare adverse effect of an anti-TNF agent and should be considered in the differential diagnosis in an appropriate clinical setting.

Footnotes

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Exarchou SA, Voulgari PV, Markatseli TE, Zioga A, Drosos AA. Immune-mediated skin lesions in patients treated with anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitors. Scand J Rheumatol. 2009;38:328–31. doi: 10.1080/03009740902922612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katz U, Zandman-Goodard G. Drug-induced lupus: An update. Autoimmun Rev. 2010;10:46–50. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ko JM, Gottlieb AB, Kerbleski JF. Induction and exacerbation of psoriasis with TNF-blockade therapy: A review and analysis of 127 cases. J Dermatolog Treat. 2009;20:100–8. doi: 10.1080/09546630802441234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Devos SA, van Den Bossche N, De Vos M, Naeyaert JM. Adverse skin reactions to anti-TNF-alpha monoclonal antibody therapy. Dermatology. 2003;206:388–90. doi: 10.1159/000069965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Voulgari PV, Markatseli TE, Exarchou SA, Zioga A, Drosos AA. Granuloma annulare induced by anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:567–70. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.075663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deng A, Harvey V, Sina B, Strobel D, Badros A, Junkins-Hopkins JM, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis associated with the use of tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitors. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:198–202. doi: 10.1001/archderm.142.2.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herti MS, Haendle I, Schuler G, Hertl M. Rapid improvement of recalcitrant disseminated granuloma annulare upon treatment with the tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitor, infliximab. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:552–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zoli A, Massi G, Pinnelli M, Di Blasi Lo Cuccio C, Castri F, Ferraccioli G. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis in rheumatoid arthritis responsive to etanercept. Clin Rheumatol. 2010;29:99–101. doi: 10.1007/s10067-009-1287-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]