Abstract

Sturge–Weber syndrome is a rare sporadic condition of mesodermal phakomatosis, characterized by purple-colored flat cutaneous cranial (face) hemangiomas (most commonly along the trigeminal nerve), glaucoma and vascular lesions in the ipsilateral brain and meninges. Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome is also an uncommon mesodermal phakomatosis characterized by a triad of cutaneous and visceral hemangiomas, venous varicosities and soft tissue or bone hypertrophy. Sturge–Weber syndrome in combination with Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome is unusual. Because of the rarity, we report here a 3-year-old boy who presented with overlapping features of both the syndromes.

Keywords: Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome, Sturge–Weber syndrome, Nevus flammeus, Hemangioma

Introduction

Sturge–Weber syndrome (SWS) is a mesodermal phakomatosis characterized by a port-wine vascular nevus on the upper part of the face, leptomeningeal angiomatosis that involves one or both hemispheres, choroidal vascular lesions associated with glaucoma, early onset seizure, neurologic deterioration and eventual neurodevelopmental delay.[1] Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome (KTS) also, a mesodermal phakomatosis is characterized by a triad of vascular malformation, venous varicosity and hyperplasia of soft tissue and bone of the affected limb.[2] Both the syndromes occur almost always sporadically. Patients with overlapping features of SWS and KTS have been reported;[3,4] however, it is extremely rare. We report here an unusual case of a 3-year-old boy with features of both SWS and KTS.

Case Report

A 3-year-old male child, who was a product of nonconsanguineous marriage, presented in our pediatric emergency with generalized tonic colonic seizures. History revealed that he had a first episode of right-sided focal convulsion at the age of 9 months, and since then, he had been on an anticonvulsant therapy. Developmental history suggested delayed milestones. Physical examination revealed that there was extensive port-wine staining over both sides of his face, extending to both lower eyelids and cheeks, with an area of bluish gray pigmentation of the episclera [Figures 1a–b]. The nevus flammeus descended on to the neck, chest and both the legs (from thighs to soles). His right lower limb showed a relative hypertrophy [Figure 1c]. There was a difference of 2 cm in length (right:left 39:37 cm) and 4.5 cm in circumference of both lower limbs (right:left 29.5:25 cm). Dilated superficial veins were noted over medial aspect of the foot as well as lateral aspect of the lower limb on the right side.

Figure 1.

(a) Extensive port-wine stain distributed over both sides of face, trunk and limbs; (b) bluish gray pigmentation of the episclera; (c) soft tissue as well as bony hypertrophy of right lower limb

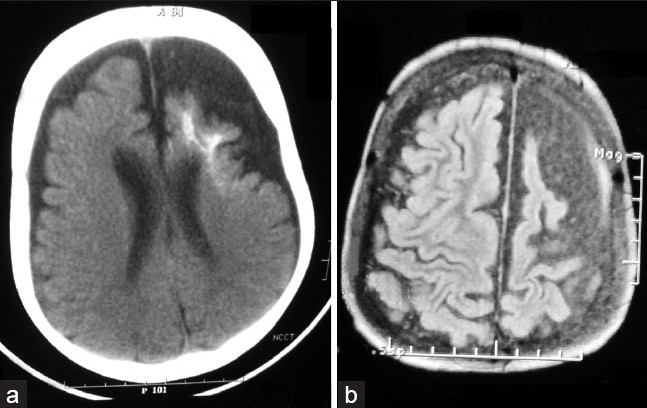

The hematologic, biochemical, and urinary laboratory tests were normal. Abdominal ultrasonography revealed no abnormality. Doppler USG of vessels of the lower extremities showed narrowing with less blood flow on right-sided venous system compared to the left. Ophthalmoscopy showed glaucomatous cupping of the disc with tortuous retinal blood vessels, more on the left side compared to right. On cranial computed tomography (CT) scan, there was atrophy in both the hemispheres along with gyral calcification on the left side. Ground glass appearance of skull bones with mild cortical thickening was also noted [Figure 2a]. Contrast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed evidence of leptomeningeal angiomatosis in the left fronto-parieto-temporal region and enlarged ipsilateral choroid plexus [Figure 2b]. MRI angiography of cerebral vessels did not demonstrate any arteriovenous communications. Electroencephalography (EEG) showed multiple epileptiform foci on both sides and voltage suppression on the left hemisphere. The patient was diagnosed to have SWS in association with KTS, according to the results of physical examination and neuroimaging.

Figure 2.

(a) Atrophy in both the hemispheres along with gyral calcification of the left side; (b) leptomeningeal angiomatosis and enlarged choroid plexus of the ipsilateral hemisphere

Discussion

SWS is a rare neurocutaneous syndrome with a frequency of approximately 1 per 50,000.[5] Encephalofacial angiomatosis[6] or encephalotrigeminal angiomatosis are used as synonyms of the syndrome as angiomas involve the leptomeninges and skin of the face, typically in the ophthalmic and maxillary distributions of the trigeminal nerve.

The classical KTS was first described by Klippel and Trenaunay in 1900. Parkes Weber syndrome is distinct from KTS by the presence of arteriovenous malformation which indicates a bad prognosis. Thus, the term Klippel–Trenaunay–Weber syndrome is an inappropriate one.[7,8] KTS affects males more often than females, with an incidence of about 2–5 per 100,000.

The exact pathogeneses of these syndromes are still not clearly elucidated.[9] There are suggestions that the majority of cases result from somatic mutations involving genes that play significant roles in embryonic vasculogenesis and angiogenesis.[10–12]

It was Schnyder et al.[13] who first bridged the gaps between these three syndromes, i.e. Klippel–Trenaunay, Parkes–Weber and Sturge–Weber syndromes. They suggested that these three syndromes are variants with a common feature of local gigantism and hemangioma. Involvement of the head and neck with manifestations of meningeal angiomatosis causing epileptic fits and choroidal hemangioma or glaucoma result in a presentation of SWS. Local gigantism and hemangioma of the limbs with osteohypertrophy presents as Klippel–Trenaunay or Parkes–Weber syndrome, depending on whether there are peripheral varices which cause KTS or arteriovenous anastomoses which would result in a picture of Parkes–Weber syndrome. It suggests that the basic pathology of all the three is the same but different presentations are observed depending on differential involvement. The other features of the syndromes are supposed to be secondary to the primary involvement of the neuro-ectodermal vasculature.

Our patient presented with nevus flammeus on both sides of face, back and leg, leptomeningeal angiomatosis on left hemisphere, convulsion and congenital glaucoma, which were consistent with SWS. He had also soft tissue as well as bony hypertrophy of the right leg along with dilated superficial veins of the affected limb, which were compatible with KTS. The uniqueness of this case was that the manifestations of SWS were more on the left side but those of KTS were exclusively on the right side. There have been sporadic case reports of association of these two syndromes.[3,4,14] However, to the best of our knowledge, contralateral involvement of the two syndromes in the same patient has not yet been documented.

Footnotes

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Sturge WA. A case of partial epilepsy apparently due to a lesion of one of the vasomotor centers of the brain. Trans Clin Soc Lond. 1879;12:162–7. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barek L, Ledor S, Ledor K. The Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome: A case report and review of the literature. Mt Sinai J Med. 1982;49:66–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deutsch J, Weissenbacher G, Widhalm K, Wolf G, Barsegar B. Combination of the syndrome of the Sturge–Weber and the syndrome of Klippel-Trenaunay. Klin Pediatr. 1976;188:464–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee CW, Choi DY, Oh YG, Yoon HS, Kim JD. An Infantile Case of Sturge-Weber Syndrome in Association with Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber Syndrome and Phakomatosis Pigmentovascularis. J Korean Med Sci. 2005;20:1082–4. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2005.20.6.1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haslam Robert HA. Sturge-Weber disease. In: Behrman RE, Kliegman RM, Jenson HB, Stanton BF, editors. Nelson's Textbook of Pediatrics. 18th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2008. p. 2487. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moe P, Seay AR. Neurologic and muscular disorders. In: Hay WW, Hayward AR, Levin MJ, Sondheimer JM, editors. Current Pediatric Diagnosis and Treatment. 16th ed. Singapore: McGraw Hill; 2003. pp. 717–92. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Atherton DJ. Naevi and other developmental defects. Vascular naevi. In: Champion RH, Burton JL, Burns DA, Breathnach SM, editors. Rook's Textbook of Dermatology. 6th ed. London: Oxford Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1998. pp. 585–8. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grevelink SV, Mulliken JB. Vascular Anomalies and Tumours of Skin and Subcutaneous Tissues. In: Freedburg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, Austen KF, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, editors. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 6th ed. New York: Mc Graw Hill; 2003. pp. 1002–19. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garzon MC, Huang JT, Enjolras O, Frieden IJ. Vascular malformations Part II: Associated syndromes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:541–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.05.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Madaan V, Dewan V, Ramaswamy S, Sharma A. Behavioral manifestations of sturge-weber syndrome: A case report. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;8:198–200. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v08n0402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Timur AA, Driscoll DJ, Wang Q. Biomedicine and diseases: The Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome, vascular anomalies and vascular morphogenesis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62:1434–47. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-4523-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tian XL, Kadaba R, You SA, Liu M, Timur AA, Yang L, et al. Identification of an angiogenic factor that when mutated causes susceptibility to Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome. Nature. 2004;427:640–5. doi: 10.1038/nature02320.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schnyder UW, Landolt E, Martz G. Syndrome de Klippel–Trenaunay avec colombe irien atypique. J Genet Hum. 1956;5:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pereira de Godoy JM, Fett-Conte AC. Dominant inheritance and intra-familial variations in the association of Sturge-Weber and Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber syndromes. Indian J Hum Genet. 2010;16:26–7. doi: 10.4103/0971-6866.64943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]