Abstract

Context and Aim:

Yoga has been found to be effective in the management of stress. This paper describes the development of a yoga program aimed to reduce burden and improve coping of family caregivers of inpatients with schizophrenia in India.

Materials and Methods:

Based on the assessment of caregiver needs, literature review, and expert opinion, a ten-day group yoga program was initially developed using the qualitative inductive method of inquiry. Each day's program included warm-up exercises, yogic asanas, pranayama, and satsang. A structured questionnaire eliciting comments on each day's contents was given independently to ten experienced yoga professionals working in the field of health for validation. The final version of the program was pilot-tested on a group of six caregivers of in-patients with schizophrenia admitted at NIMHANS, Bangalore.

Results:

On the question of whether the program would help reduce the burden of caregivers, six of the ten experts (60%) gave a rank of four of five (very much useful). Based on comments of the experts, several changes were made to the program. In the pilot-testing stage, more than 60% of the caregivers assigned a score of four and above (on a five-point Likert scale, five being extremely useful) for the overall program, handouts distributed, and performance of the trainer. Qualitative feedback of the caregivers further endorsed the feasibility and usefulness of the program.

Conclusion:

The developed yoga program was found to be acceptable to caregivers of in-patients with schizophrenia.

Keywords: Family caregivers, need, schizophrenia, yoga

INTRODUCTION

Yoga models described by earlier authors have provided their own rationale behind the choice of yoga asanas/program.[1–3] However, there is no mention whether these programs have been endorsed by other specialists in the field than the researcher themselves. Also, there is no literature which discusses the development of a yoga program which attempts to match the expressed needs of the participants.

Only two studies have looked at development and feasibility testing of yoga programs for caregivers of persons with disability. Puymbrock et al.[4] tested the feasibility of a yoga program on the physical health and coping of informal caregivers who cared for a person with a disease or disability in USA. Waelde et al.[5] conducted a pilot study of a yoga and meditation intervention called “Inner Resources” for dementia caregiver stress in USA.

The above studies focus more on feasibility testing rather than on the development of a yoga program. The cultural applicability of the studies in an Indian setting would also require testing. Furthermore, the needs expressed by the caregivers of persons with dementia[6–9] is different from that of the needs of caregivers of persons with schizophrenia.[10] As there were no Indian studies which explored the development and feasibility testing of yoga program based on the needs of caregivers, we undertook the systematic development of a yoga program based on the needs of caregiver of persons suffering from schizophrenia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was reviewed and approved by the Institute's ethics committee. Written informed consent of the mental health professionals who helped in validation of the program and family caregivers who participated in the pilot study was obtained. A sociodemographic sheet eliciting information on their age, occupation, monthly income, and marital status was filled up by the researcher for both the mental health professionals and family caregivers.

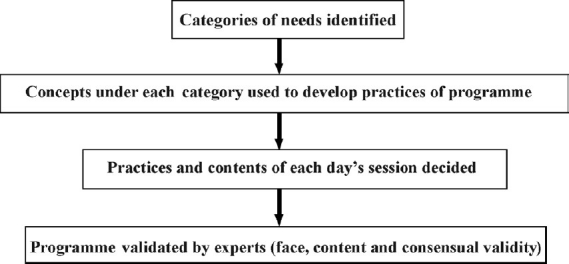

The inductive method of inquiry (quintessence of qualitative research) in which general principles (theories/programs) are developed from specific observations was used to develop and test the feasibility of the program. The development of the yoga program was conducted in two stages. Stage-one involved development of the content and methodology for the yoga program. Stage-two involved face and content validation of the program. The feasibility of the program was tested in Stage-three of the study where the program was pilot-tested and feedback from the caregivers who participated in the program was elicited. The process involved in each stage of the development and feasibility testing of the program is delineated below [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Process of Inductive method of program development

Stage-One: Program development

Initially, a yoga program was developed by matching the needs of the caregivers.[10] Classical texts such as Patanjali Yoga Sutra,[11] Rigveda,[12] Gheranda Samhita,[13] Hatharatnavali,[14] and Hathayogapradipika[15] were reviewed to understand the asanas/practices that would help directly or indirectly deal with each of the needs.

To help warm up the body to practice the asanas and pranayama, jogging, cycling, and hands in and out breathing was incorporated in the beginning of each day's program (Nagendra, 2008).

Suryanamaskara a set of yogic postures done in a sequence of postures routinely followed in several yoga schools, helps in bringing about general flexibility of the body and improving mental health as a preparation for asanas and pranayama (Satyananda Saraswati, 2008; Yogendra., 1997). Even the foremost classical text (Rigveda, 1st Mandala, 50th Sukta) emphasizes the benefits of the practice in destroying physical illnesses and the diseases of the heart (mind) [‘udyannadya mitramaha arohannuttaram divam /Hrdrogham mamasurya harimanam ca nasaya // (1st Rucha). “Rising this day, O rich in friends, ascending to the loftier heaven, Surya remove my hearts disease, take from me this yellow hue…”].

The goal of yoga practices in context of the needs expressed by the caregivers (such as managing illness behavior, managing socio-occupational concerns, physical and mental health, and managing marital and sexual issues of the patient) was to enable the caregivers to think clearly, have equanimity in emotions, improve their decision making as well as their response to a situation, and improve their attention. A review of classical yoga texts (Gheranda Samhita, Hatharatnavali, Hathapradipika) and contemporary yoga textbooks (Yogendra., 1997, Satyananda Saraswati, 2008; Nagendra, 2008) showed that asanas such as Padahastasana, ardhachakrasana, Vajrasana, Vakrasana, Salabhasana Bhujangasana, Savasana, Nadanusandana, Matsyasana, Nadishuddhi, Bhramhari, and Kapalabhatti had direct or indirect benefits in improving caregiver's ability to think clearly, improve their decision making/response to a situation/attention, and equanimity of emotions.

The satsang was used to educate the caregivers on how yoga could help tackle their needs and help in rehabilitation of the patient.

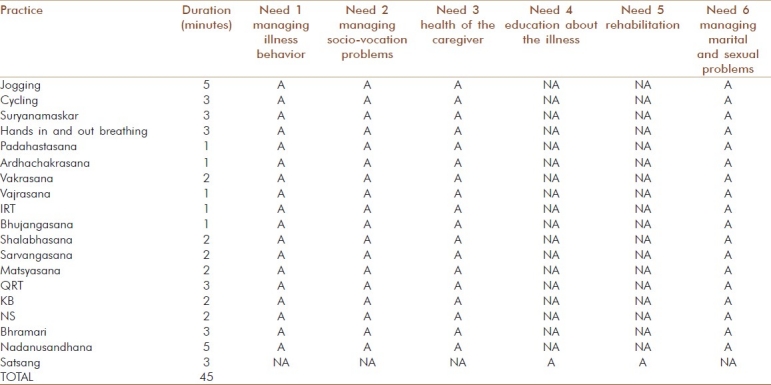

Table 1 depicts the details of the yoga program developed in accordance with the assessed needs of caregivers. The table enlists practices that are applicable/not applicable in fulfilling the six assessed needs of the caregivers.

Table 1.

Yoga program in accordance to needs of caregivers [Practices applicable (A)/not applicable (NA)]

The ultimate aim of the yoga program was to reduce the burden of the caregivers either by addressing their needs or by developing yoga program which in turn would equip them with the ability and skills to reduce their burden—irrespective of the fulfillment of needs. As not all needs could be theoretically addressed by teaching yoga, we focused on the reduction of burden (aim of the study), irrespective of the expressed needs.

Thus, the framework of the yoga program was based on Integrated Yoga Therapy (IAYT) model developed by Swami Vivekananda Yoga Anusandhana Samasthana[3] (SVYASA). This model incorporated the “Self Management of Excessive Tension (SMET)/ Cyclic meditation” approach which reflected not only the aim of the current study of reducing burden and improving coping among the caregivers, but also directly or indirectly dealt with the six broad categories of assessed needs elucidated in the first phase of this study.[10]

Stage-Two: Face and content validation

For the purpose of content validation of the program, the researcher developed a structured questionnaire eliciting dichotomous responses such as Yes/No and qualitative comments on the appropriateness of each exercise and asana selected as a component of the entire yoga program. Ten experienced yoga therapy and research professionals (in and around Bangalore) were approached individually for the validation. The average number of years of work experience (SD) of the experts after their formal education was 14.8 (14.1) years. Through this methodology of content - validation, the researcher accumulated a list of comments for incorporating into yoga program. For face validation of the program, the researcher asked each of the professionals to rate the likelihood of the program achieving its objective of helping the caregivers reducing their burden and stress - on a five point Likert scale.

To arrive at a consensus on the contents and methodology of the yoga program, three rounds of iteration was conducted among the yoga professionals, i.e., the researcher made changes to the program based on comments given by the professionals and went back (iteration) to them for their further inputs on the modified program, three times before all the ten experts agreed on the contents and methodology (data saturation).

A standardized script of the final version of the yoga program was developed on incorporating the comments of the ten experts. The script included list of practices and asanas along with their step-wise procedure and pictures, detailed notes on each satsang topic (seven topics – one topic for each day; the script is available from the authors on request). A handout explaining the contraindication of practicing certain asanas during ailments along with the order and list of yogic practices and their pictures was developed in four languages (English, Hindi, Kannada, and Tamil) for distribution to the participants. Each satsang topic and notes was converted into power point slides in the four languages for ease of presentation to the participants.

Stage-Three: Pilot study and feasibility

The final version of the yoga program was pilot-tested on a group of eight in-patient family caregivers who were residing at National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences (NIMHANS) in Bangalore, India (NIMHANS has a 900-bed teaching hospital with training and research facilities in psychiatry and other neurosciences) during the period of the study.

Caregivers of patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia were included in the study if they were to continue to provide care for them following discharge. Caregivers with psychiatric or neurological disorders and those caring for another relative with psychiatric illness were excluded. Of the eight caregivers recruited in the pilot study, three caregivers dropped out during the intervention. The mean age (SD) of the caregivers who completed the program was 49.6 (19.5) years. They had an average of 10.4 (3.8) years of education. All of them were females and three of the caregivers were parents. The average (SD) duration of illness of their patients was 12.2 (8.2) years and none of them had not received any prior structured training on how they should take care of their patient.

Participants were trained in performing yoga asanas under the guidance of a trained yoga therapist (based on the script developed; therapist trained by SVYASA). The intervention included sessions of about one hour daily for a period of seven days. During the entire period of the study, the ill relative continued to receive the routine treatment prescribed by the doctors at NIMHANS. At the end of the seven days, the caregivers were asked to fill a structured feedback form on their overall rating of the program, trainer, and the handouts distributed during the sessions.

Descriptive analysis of the quantitative (Likert ratings) feedback and content analysis of the qualitative feedback received from the caregivers was conducted. Each and every comment was given importance and the researcher tried to accommodate all of it into the yoga program.

RESULTS

As the main objective of the study was to develop and test the feasibility of a need-based yoga program for inpatient caregivers, the results reflect the qualitative data acquired at two levels: at the validation stage and at the pilot stage.

At validation stage

For content validation, experts were asked for their feedback on the components that should be added in the IAYT model [incorporating the ‘Self Management of Excessive Tension’ (SMET)/ Cyclic meditation approach]. The suggestions given by the experts are elicited below:

Breathing exercises (like ‘Bhujangasana breathing’ and ‘Salabhasana breathing′) need to be included.

Chanting either with the breathing exercises or separately (Nadanusandana) should be included as it would increase the exhalation: inhalation ratio and hence (in all probability) stimulate the parasympathetic tone, which would be useful in stress reduction.

Emphasis on awareness of calmness and silence from within during asana practice is of vital importance. For this reason, explanations of the purpose of the asanas should be done in the introduction or during ‘Satsang’ at the end.

Teach the full round of 13 practices of ‘suryanamaskara’ with invocation at the beginning of each for at least six minutes.

I am personally used to ‘Padahastasana’ at the end, once the body and legs are softened. It is a good preparation for final ‘Savasana’ (or Quick Relaxation Technique - QRT).

‘Paschimuttanasana’ or ‘Halasana’ can feature in the list as these two (possibly in combination with Sarvangasana) are ideal for loosening up the region of the ‘Muladhara chakara’ and inducting the shakti to flow more strongly.

Twist poses are excellent for refreshing blood flow to all the inner organs in the abdomen, from which the renewed flow of the various pranas in the nadis/meridians transform how a person feels. In this context, even the rotating swings performed during loosening exercises could be useful as a 1-minute practice during the warm-up period.

Sarvangasana is the best position for becoming aware of the inner silence and could well be put at the beginning.

To add deep breathing, nadishodhana and Kapalabhatti in the program which should be practiced frequently, example: while attending satsang.

Caregivers need to consciously focus on the ‘stretch’ which maintains easy and relaxed breathing during asana performance. This has the most powerful calming and integrating effect.

Based on the comments given by the experts, the yoga program was appropriately modified and developed for a seven-day period of one hour each (inclusive of 45 minutes of practices and 15 minutes of satsang). The program started with loosening exercises, five rounds of 13 step ‘suryanamaskara’ excluding invocation (due to lack of time), cyclic meditation, ‘Kapalabhatti’, ‘Nadishuddhi’ pranayama, and chanting (Nadanusandana). Emphasis was on awareness of calmness and silence from within during asana practice. For this reason, explanations about the benefits of each asana was given during the practice and included as topics for the ‘Satsang’ at the end of each day's program. Caregivers were consciously taught to focus on the ‘stretch’ with maintaining easy and relaxed breathing during asana performance. Paschimuttanasana’, ‘Halasana’, and Sarvangasana were excluded from the program as the authors felt that it would be challenging for the caregivers to learn and practice these asanas due to their age.

For face validation, on asking whether the overall yoga program would achieve its objective of helping the caregivers reduce their burden and stress, six of the ten experts (60%) gave a rank of four (very much useful).

At pilot stage

Of the five caregivers who underwent the pilot yoga program, four of them assigned a score of four or five (on a five-point Likert scale, five being extremely useful) for the overall program, handouts distributed, and performance of the trainer. Qualitative feedback of the caregivers further endorsed the feasibility and usefulness of the program (M: Member):

“The entire program was good as it taught us the importance of taking care of our own health. I liked to attend the program” (M1).

“I liked the program as it helped to reduce my physical problem (leg pain) and gave me a relaxed feeling” (M2).

“The program helped me to understand the problem (of my health) and find a way to get relief. I liked the chanting of slokas the best.”(M3)

“The instructor and her way of teaching were very good. Also I feel Suryanamskar benefitted me the most.” (M5).

DISCUSSION

The challenges faced by caregivers in dealing with their relative who is suffering from schizophrenia are varied and extensive. A number of interventions offered to family members with patients of schizophrenia have been developing to help deal with the burden and stress of caring. The current study in an attempt to develop a need-based yoga program describes the steps involved in the program development, content and face validation, and pilot testing of the program.

There is hardly any research study that discusses the development and effectiveness of standardized training programs based on the assessed needs of caregivers of persons suffering from schizophrenia in India. This attempt to develop a structured intervention program based on the holistic coverage of all the needs of the family caregivers—via a participatory approach (i.e., the caregivers themselves opined their needs and areas they required training in which was incorporated to develop the program) is of significant importance, even though we were unable to match all the needs of the caregivers to the contents of yoga program (where the focus was more to reduce burden of the caregivers).

The yoga program was developed after a lot of collective thought and scientific rigor. The possible effects of each asana and exercise on the physiology and mental health of the caregiver was weighed to retain the asana/exercise in the program (whether it physiologically reduced the stress and mentally reduced burden and improved coping). A number of related factors such as age and possible health conditions of the caregiver were taken into consideration before incorporating a particular asana/exercise into the program. Experts had opined the importance of educating the caregivers about the benefits of the asanas/exercises at the onset or during the satsang—incorporation of which helped caregiver gain greater awareness of the subtle changes in the physical and mental state over the period of the program.

Though a few experts were skeptical of the effects of yoga in helping caregivers relieve their burden and stress, majority of them felt that the overall yoga program would achieve its objective. Skepticism could be valid, as both concepts of burden and stress are complex. Varied practical issues could weigh on the caregivers’ mind when asked to rate their burden—example, financial burden and stress in caregivers is a prolonged effect of enduring certain unresolved practical problems.

Another critique of the above program was that it was too short to enable the caregivers to imbibe the yoga techniques into daily practice. Traditional yoga therapists would argue that the seven-day program could be too short to perceive any effects of yoga. However, development of an elaborate program in the current setting would have its own limitations, mainly being that of high drop-outs and inability to reach out to majority of the caregivers. This is mainly because the average period of stay of a patient and his caregiver in any psychiatric setting is less than one week. The statistics at NIMHANS depict the average stay of in-patients and their caregivers as three weeks. However, as the patient is usually acutely symptomatic in the first week, it is challenging to conduct any intervention with the caregiver alone, as there is no one else to take care of the patient. There are many barriers like convincing people to travel long distances from their homes to a center for yoga therapy/psychosocial interventions[16] once they are discharged. In this context, we believe that our seven-day program was pragmatic in its timeline and achieved its goal of reaching out to maximum caregivers who were admitted in the wards along with their patients at NIMHANS, during the study period.

The sociodemographic profile of the caregivers who participated in the programs was consistent with that of earlier studies on Indian caregivers of persons with schizophrenia.[17,18] All caregivers were family members. Most of them were parents, who were working and were into late adulthood or old age.

The feasibility and usefulness of the yoga program was endorsed by the caregivers. The fact that the caregivers were able to perform all the asanas properly, understand its benefits, and feel relaxed indicates that the program was feasible and could be tested on a larger population.

CONCLUSION

This study is one of the first studies to use a sound methodology of inductive enquiry model for the development of a need-based yoga program for caregivers of in-patients with schizophrenia in India. These findings are highly indicative and future studies could test the efficacy of the program with a larger quantitative sample to reconfirm its validity, reliability, and generalizability. The researchers plan to test the efficacy of this validated yoga program for family caregivers of inpatients with schizophrenia in India in a larger randomized control trial, as an outcome of this study.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The team would like to thank Dr. Hariprasad VR (Senior Research Fellow, Advanced Centre for Yoga, NIMHANS) and Meghna S Deshpande (Yoga instructor) for their contribution in designing the yoga program.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yogendra . Yoga Asanas simplified. Mumbai, India: Yogendra Publication Fund – The yoga Institute; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Satyananda Saraswati. Asana Pranayama Mudra Bandha. Munger, Bihar, India: Yoga publications trust; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nagendra HR, Nagarathna R. Vivekananda Yoga Research Foundation. Bangalore: Swami Vivekanand Yoga Prakashana; 2008. New perspectives in stress management. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Puymbroeck MV, Payne LL, Hsieh PC. A phase I feasibility study of yoga on the physical health and coping of informal caregivers. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2007;4:519–29. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nem075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Waelde LC, Thompson L, Gallagher-Thompson D. A pilot study of a yoga and meditation intervention for dementia caregiver stress. J Clin Psychol. 2004;60:677–87. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peeters JM, Van Beek AP, Meerveld JH, Spreeuwenberg PM, Francke AL. Informal caregivers of persons with dementia, their use of and needs for specific professional support: A survey of the National Dementia Program. BMC Nurs. 2010;9:9. doi: 10.1186/1472-6955-9-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosa E, Lussignoli G, Sabbatini F, Chiappa A, Di Cesare S, Lamanna L, et al. Needs of caregivers of the patients with dementia. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2010;51:54–8. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lai CK, Chung JC. Caregivers’ informational needs on dementia and dementia care. Asian J Gerontol Geriatr. 2007;2:78–87. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colantonio A, Cohen C, Pon M. Assessing support needs of caregivers of persons with dementia: Who wants what? Community Ment Health J. 2001;37:231–43. doi: 10.1023/a:1017529114027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jagannathan A, Thirthalli J, Hamza A, Hariprasad VR, Nagendra HR, Gangadhar BN. A qualitative study on the needs of caregivers of inpatients with schizophrenia in India. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2011;57:180–94. doi: 10.1177/0020764009347334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iyengar BK. Light on the yoga sutras of patanjali. London: Harper Collins Publishers; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sontakke NS, Râjvade VK, Vâsudevaśâstri MM, Varadarâjaśarmâ TS. Rigveda-Samhitâ: Śrimat-Sâyanâchârya virachita-bhâṣya-sametâ. First ed. Pune, India: Vaidika Samśodhana Mandala; 1933. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swami Digambarji, Gharote ML. Gheranda Samhita. 1st ed. Lonavala (India): Kaivalyadhama S.M.Y.M Samiti; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gharote ML, Devnath P, Jha VK. Hatharatnavali (A treatise on Hathayoga) of Srinivasayogi. Lonavala: The Lonavala Yoga Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Svatmarama . Hatha Yoga Pradipika of Svatmarama. 4th ed. Adyar (Madras, India): Adyar Library and Research Centre; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baspure S, Jagannathan A, Varambally S, Thirthalli J, Nagendra HR, Venkatasubramanian G, et al. Barriers to yoga therapy as an add on treatment for schizophrenia - data from a clinical trial. Paper presented by Dr. Shubhangi B at the National Conference on Naturopathy and Yoga, Recent Research Trends, Jindal Nature Cure Hospital, Jindal Nagar Tumkur Road Bangalore. 2009 Jan [Google Scholar]

- 17.Srinivasan N. Together we rise-kshema family power. In: Murthy RS, editor. Mental Health by the People. Bangalore: Peoples Action for Mental Health (PAMH); 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murthy RS. Mental health by the people. Bangalore: Peoples Action for Mental Health (PAMH); 2006. [Google Scholar]