Abstract

Aim:

To describe the possible barriers to yoga therapy for patients with schizophrenia in India.

Materials and Methods:

In a randomized control trial at NIMHANS, patients with schizophrenia (on stable doses of antipsychotics, 18–60 years of age, with a Clinical Global Impression-Severity score of 3 or more) were randomized into one of three limbs: Yoga therapy, physical exercise and waitlist. Of 857 patients screened, 392 (45.7%) patients were found eligible for the study. Among them, 223 (56.8%) declined to take part in the trial. The primary reasons for declining were analyzed.

Results:

The primary reasons for declining were (a) distance from the center (n=83; 37.2%); (b) no one to accompany them for training (n=25; 11.2%); (c) busy work schedule (n=21, 9.4%); (d) unwilling to come for one month (n=11; 4.9%), (e) not willing for yoga therapy (n=9, 4.0%); (f) personal reasons (n=3, 1.3%); (g) religious reasons (n=1, 0.4%). In 70 patients (31.6%), no reasons were ascribed. No patient refused citing research nature of the intervention as a reason.

Conclusion:

More than half of the patients eligible for yoga did not consent to the study. Logistic factors, such as the need for daily training under supervision in a specialized center for long periods, are the most important barriers that prevent patients with schizophrenia from receiving yoga therapy. Alternative models/schedules that are patient-friendly must be explored to reach the benefit of yoga to patients with schizophrenia.

Keywords: Barriers, schizophrenia, yoga

INTRODUCTION

Schizophrenia is ranked as the ninth leading cause of disability in people worldwide.[1] Pharmacotherapy is the mainstay in the management of schizophrenia. However, even with the best drugs available to treat schizophrenia, refractoriness, negative symptoms, frequent relapses, and persisting cognitive impairment still persist.[2]

For this reason, researchers have studied alternative and complementary strategies such as yoga to help patients with schizophrenia. Studies on efficacy of yoga in patients with schizophrenia have shown improvement in cognitive skills, physiological parameters and psychopathology.[3–5]

In this context, a single blind randomized controlled study was conducted in NIMHANS, to assess the effectiveness of yoga as an add-on treatment for persons with schizophrenia. It was found that in spite of offering yoga, explaining its potential benefits and providing travel support to attend the training, a number of patients were not able to come for the yoga training. In order to make yoga acceptable and available to the patient population, it is essential to understand the possible barriers to yoga therapy for patients with schizophrenia. This paper is an attempt in that direction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample

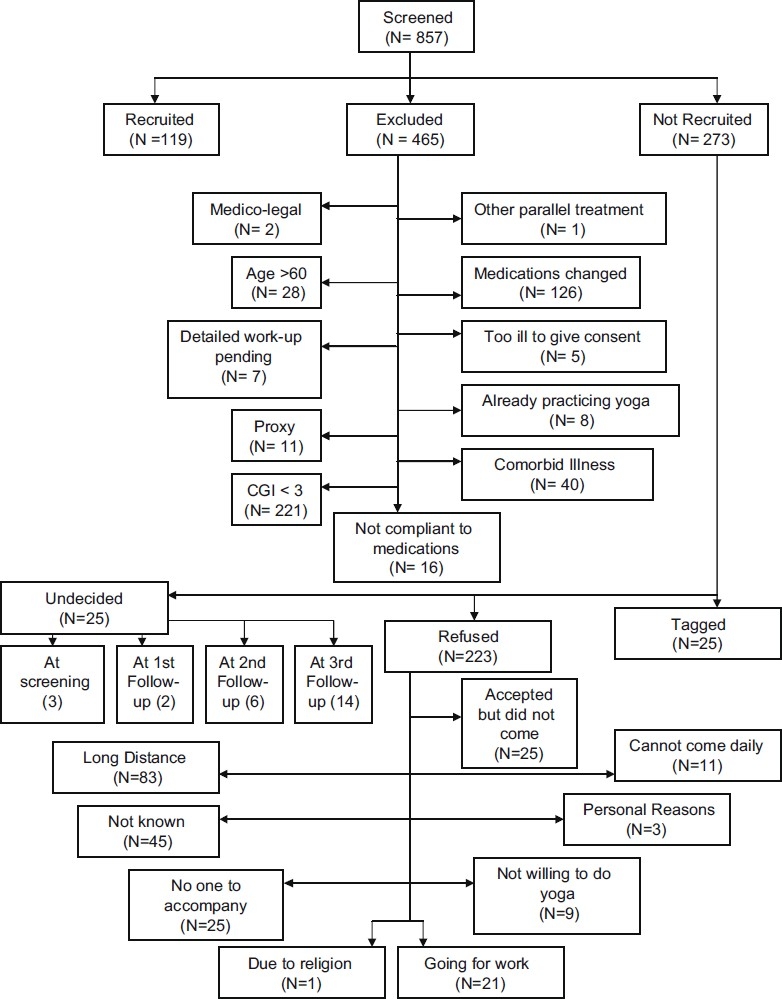

In order to achieve the target sample of 120 patients for the larger randomized controlled study (three groups: Yoga group, physical exercise and waitlist group), the researchers screened 857 patients with schizophrenia who presented to NIMHANS outpatient department over a 15 month period. To be eligible, the patient was required to have a diagnosis of schizophrenia (diagnosed according to DSM-IV), an illness severity on clinical global impression ≥3, age 18-60 years and, residing in and around Bangalore. Patients who had co morbid mental retardation, serious neurological illness or epilepsy were also excluded. Out of the total screened patients, 392 were found eligible and 465 not eligible for the study. These 392 patients were offered an option to participate in the current study. Between the period 7th March 2008 and 28th May 2009, 119 patients accepted to participate in the study and 223 refused [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Sampling procedure

Design, tools and procedure

The current study adopted a descriptive research design. Patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria were explained about the study design and were invited to participate in the study.

A log of patients screened for the project was maintained. This log contained details of patient's name, file number, age, sex, address, contact number and information on whether the patient has agreed to participate in the study. If the patient had refused to participate, the reasons for refusal were recorded verbatim. The first reason that was spontaneously stated was analyzed in the sample.

RESULTS

The mean age of patients who refused for the study was 34.8 years (10.13 SD) and 38% of them were females. Patients who refused to participate in yoga seemed to be older [34.8 (10.13) years] than patients who agreed to participate [33.2 (9.3) years; P=0.09]. There was no difference in gender distribution of patients who agreed for the study as compared to those who refused.

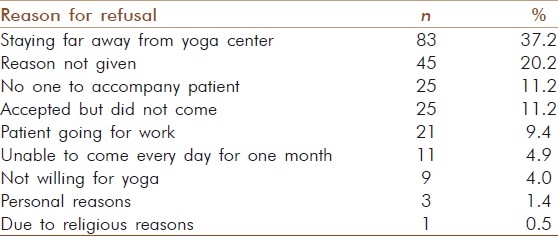

The reasons for refusal were (a) staying far away from the center (n=83; 37.2%); (b) no one to accompany patient for training (n=25; 11.2%); (c) patient cannot miss work (n=21, 9.4%); (d) unable to come every day for one month (n=11; 4.9%); (e) not willing for yoga (n=9, 4.0%); (f) personal reasons (n=3, 1.3%); (g) religious reasons (n=1, 0.4%). In 70 patients, no reason was ascribed, though 25 of these had agreed to come but dropped out. No patient refused citing research nature of the intervention as a reason [Table 1].

Table 1.

Reasons for refusal

DISCUSSION

The results of the study bring out the barriers to attend yoga therapy such as staying far away from the center, there was no one to accompany patient for yoga, patient was going for work, inability to come daily for yoga for one month, personal reasons and unwillingness to practice yoga due to religious reasons. The above findings need to be understood in the context that, except for a few scientific research studies;[3,5] yoga for schizophrenia is a relatively new treatment methodology. Thus, there is a possibility that both mental health practitioners and patients are skeptical about the effectiveness of this new treatment. There has also been some debate on whether people from faiths other than Hinduism should practice yoga.[6]

The yoga training especially in the case of treatment of persons with mental illness needs to be given by a trained yoga therapist.[7] Though yoga has its roots from ancient India, it is widely taught as a treatment methodology only in the urban centers where a few trained yoga instructors are available.[8] This could be difficult for those patients who stay far away from the yoga center and find it difficult to avail of the treatment on a daily basis. Reasons of a clinical trial as the reason for refusal did not Figure as the first in the entire sample. However, a sizeable sample did not provide any reasons for their refusal. Hence, the nature of a clinical trial and random allocation to yoga could be one of the reasons in the sample who refused to partake in the study. Patients, who were inhibited to say this as the first reason, may have abstained from stating so.

Further the treatment of yoga has a different course as against biological treatments like medications, which hardly require a few minutes to administer. The lengthy course of yoga treatment[9] could act as a barrier for patients who are working and cannot take out time every day for the treatment.

Medication and treatment adherence is a big barrier in treating psychiatric illness like schizophrenia,[10] as most patients do have insight about their illness. Further the nature of schizophrenia itself, where patients experience negative symptoms,[11] may make it difficult for them to attend the yoga treatment consistently for the required period of time. This could explain why some patients, who agreed to participate, did not attend the yoga sessions. It was challenging to motivate out-patients to regularly attend the yoga classes for one month daily. Routinely patients attend outpatient follow ups once in two months only. Offer of bus fares to patients and their relatives to come for intervention daily produced some effects with regards to treatment adherence. Further, due to the nature of the illness, caregivers often need to accompany the patient to the daily treatment sessions. Caregivers may also have their own personal commitments due to which they may find it difficult to adhere to the yoga treatment regime. Certain other issues that merit discussion are:

-

(1)

Yoga as add-on to conventional treatment: In this study, patients who were on outpatient follow up with stabilized medication status were included. Patients thus had already obtained best benefits from conventional interventions. Follow up medication helped prevent relapses. Though most patients had residual symptoms like negative syndrome, cognitive deficits and poor social functioning (CGI rating ≥3 or mean duration of illness was close to 10 years), they were not actively symptomatic at the stage of recruitment for the study. In this context, both patients and their caregivers could have been skeptical of trying any new intervention.

-

(2)

User-friendly yoga intervention: The refusal rate in this study was high. Refusal occurred despite limiting the yoga treatment to only four weeks of daily supervised interventions as well as support to patients and families for bus fares. Among those who did not enter the study after being found suitable, one of the reasons was inability to attend yoga sessions daily. Clearly, this demands an alternative and flexible approach. Yoga modules have to be designed that demand fewer days for training. Three days a week program may offset this difficulty and motivate more patients to accept yoga as an add-on intervention. As follow up patients attend OPD once in one or two months, an intensive training session on that day may be more acceptable. These visits may be used to gradually train the patients in the entire module of yoga over several visits. There is a need to evaluate such unconventional regimens of yoga therapy. Reaching yoga to patients through community yoga program is yet another alternative. More research is needed to develop evidence-based yoga modules for schizophrenia patients.

One of the major limitations of the study was its homogeneous sample. Only patients who had Clinical Global Severity rating of 3–5 were chosen for the study, thus excluding a large number of patients who were either recovering from schizophrenia or who were too symptomatic to be recruited into yoga treatment. Further only out-patients pursuing treatment in one mental hospital were included in the study. Thus the generalizability of the results may be limited.

CONCLUSION

Given that yoga may prove to be a cost-effective addition to the current treatment methods available for schizophrenia, there is a pressing need to understand the barriers to yoga treatment such as daily training under supervision in a specialized center for periods as long as one month. Yoga schedules that may be more user friendly merit testing. The module itself needs to be made more attractive and reachable to patients closer to their residences. Less frequent supervised training, graded increase in duration of sessions by yoga therapists to patients in smaller groups, could help increase the acceptance for yoga. Programs aiming to reach yoga to patients with schizophrenia in the larger community should be cognizant of these difficulties. Further, effective marketing of yoga by all mental health professionals is an important step in making yoga accepted as an add on treatment modality for schizophrenia.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil,

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Murray CJL, Lopez AD. The global burden of disease; A Comprehensive assessment of Mmortality and disability from diseases, injuries, and risk factors in 1990 and projected to 2020. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kane JM, Honigfeld G, Singer J, Meltzer HY. Clozapine for treatment resistant schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;45:789–96. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800330013001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nagendra HR, Telles S, Naveen KV. An integrated approach of Yoga therapy for the management of schizophrenia. Final report submitted to the Dept. of ISM and H. New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lukoff D, Wallace CJ, Liberman RP, Burke K. A holistic program for chronic schizophrenic patients. Schizophr Bull. 1986;12:274–82. doi: 10.1093/schbul/12.2.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duraiswamy G, Thirthalli J, Nagendra HR, Gangadhar BN. Yoga therapy as an Add-on treatment in the management of patients with schizophrenia-A randomized controlled trial,”. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2007;116:226–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller E. Is hatha yoga religiously neutral? Charlotte, NC, US: Christian Research Institute; 2009. [Last cited on 2011 Jan 04]. Available from: http://www.equip.org/articles/hatha-yoga-religiously-neutral . [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown RP, Gerbarg LP. Sudarshan Kriya Yogic Breathing in the treatment of stress, anxiety and depression: Part II—Clinical applications and Guidelines. J Altern Complement Med. 2005;11:711–7. doi: 10.1089/acm.2005.11.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramesh A, Hyma B. Traditional Indian medicine in practice in an Indian metropolitan city. Soc Sci Med Med Geogr. 1981;15:69–81. doi: 10.1016/0160-8002(81)90017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaya MS, Kurpad AV, Nagendra HR, Nagaratna R. The effect of long term combined yoga practice on the basal metabolic rate of healthy adults. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2006;6:28. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-6-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thirthalli J, Venkatesh BK, Kishorekumar KV, Arunachala U, Venkatasubramanian G, Subbakrishna DK, et al. Prospective comparison of course of disability in antipsychotic-treated and untreated schizophrenia patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2009;119:209–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sadock BJ, Sadock VA. Kaplan and Sadock's synopsis of psychiatry: Behavioral sciences/clinical Psychiatry. North American Edition Philadelphia, Pa, US: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 1983. [Google Scholar]